Abstract

This article presents an editorial perspective on the challenges associated with e-mail management for academic physicians. We include 2-week analysis of our own e-mails as illustrations of the e-mail volume and content. We discuss the contributors to high e-mail volumes, focusing especially on unsolicited e-mails from medical/scientific conferences and open-access journals (sometimes termed “academic spam emails”), as these e-mails comprise a significant volume and are targeted to physicians and scientists. Our 2-person sample is consistent with studies showing that journals that use mass e-mail advertising have low rates of inclusion in recognized journal databases/resources. Strategies for managing e-mail are discussed and include unsubscribing, blocking senders or domains, filtering e-mails, managing one’s inbox, limiting e-mail access, and e-mail etiquette. Academic institutions should focus on decreasing the volume of unsolicited e-mails, fostering tools to manage e-mail overload, and educating physicians including trainees about e-mail practices, predatory journals, and scholarly database/resources.

Keywords: electronic mail, open-access publishing, predatory journal, professional burnout, spam e-mail, time management

Introduction

Administrative burden can occupy a significant amount of physician time, resulting in decreased career satisfaction and burnout. In surveys, physicians report administrative tasks consume 16% to 24% of their work hours.1-3 Today, 44% of physicians feel burnout, with administrative tasks being the largest contributor.4

The term e-mail overload was first described in the literature in 1996 by Whittaker and Sidner.5 It refers to users’ perceptions that their own e-mail use has gotten out of control because they receive and send more e-mails than they can handle and/or process effectively.6 The introduction of the smartphone has made e-mail even more accessible, with 84% of physicians using smartphones for their job—both during work hours and during off-hours.7 The ability to access e-mails throughout the 7-day week has potential benefits and disadvantages. For example, physicians may be able to postpone nonurgent e-mails during regular worktime and catch-up during other times such as evening, weekends, and conferences. On the negative side, continual access to e-mail can contribute to screen fatigue, burnout, sleep disturbances, and interfere with other activities and interests.8-10

At academic medical centers, physicians risk developing e-mail fatigue from high volumes of unwanted and unsolicited e-mails.11,12 Spam is a term that often refers to unsolicited, undesired, and unwanted e-mail communications, frequently from commercial sources.11 “Academic spam e-mail” is a term that has been applied to these e-mails directed toward academicians.13 In 2 single-author editorials, a pediatrician at an East Coast academic medical center received 2035 mass distribution e-mails over a 12-month time period,12 and over a 3-month time period, an academic oncologist received over 6 spam e-mails per day, with more than half being invitations to submit a manuscript to a journal or attend a scientific/medical conference.11 A high percentage of the journals were open-access publications, a subset of which have been referred to as “predatory” journals due to characteristics such as unclear editorial oversight, overly broad coverage of disparate scientific/medical fields, absent or minimal peer review, promises of rapid publication, and aggressive e-mail marketing techniques.14-17

A 2015 study reported almost 80% of electronic journal invitations were to journals on Beall’s list, a now defunct journal “blacklist” created by a University of Colorado librarian to identify journals and publishers associated with potentially predatory publications.18 The volume of spam e-mails received is directly related to academic rank and publication history (including prior history of publishing in open-access journals), with even early career faculty and trainees receiving these e-mails.13,19,20 Predatory or fraudulent scientific/medical conferences (including webinars) may similarly be of low quality and scientific value (or even not really exist) and also use mass e-mail marketing. There is less published literature analyzing e-mails from scientific/medical conferences. Unlike journals, there are not systematic databases or resources to evaluate or compare conferences. The volume of e-mails from journals and conferences alone can be substantial, with one study demonstrating 3 professors in an academic pathology department receiving between 67 and 158 unsolicited e-mails in a single-week study from journals and conferences.19

Illustration of the Challenge—2 Weeks of E-Mails for 2 Academic Physicians

As an illustration of the challenges associated with e-mail, the 2 coauthors (a clinical pathologist and hospital-based pediatrician) analyzed volume and characteristics of e-mails they received over a 2-week time period (January 14, 2019, through January 27, 2019) that included a university recognized holiday, Martin Luther King Junior (MLK) Day. During the 2-week time period, e-mails received in the inbox and spam (junk mail) folders were collected. The institution uses Microsoft Outlook 2010 as the primary e-mail platform and uses e-mail as a common route for announcements and broadcasts. Due to user complaints on e-mail volumes, the institution has undertaken multiple initiatives to reduce mass e-mail volume, including consolidation of nonurgent health-care information and broadcasts into a daily digest and options for opt-out of some mass university communications (which neither coauthor has yet opted for). E-mails were received through an institutional e-mail address run through the institutional firewall and spam filter. Neither author has modified these settings for their own e-mail.

E-mails were categorized manually by the receiver into 2 broad groups: solicited/work-related and unsolicited. Solicited/work-related included all the e-mails related to job activities and also e-mails originating from professional societies to which the 2 physicians belonged, including e-mails from list serves associated with these societies that the physicians chose to subscribe to. Work-related e-mails could include those related to conferences and journals that the physicians were intentionally involved with (eg, e-mails related to submission or peer review of a manuscript or book) or to communication with vendors or other outside entities related to work activities. Unsolicited e-mails included the following categories: conferences/webinars, journals, vendor solicitations/advertisements for products or services, miscellaneous spam (eg, phishing attacks, romance scams, advance fee frauds, investment, or financial scams), and e-mail sorted by the institutional default e-mail filter into the Junk/Spam folder. Examples of unsolicited conference/webinar and journal e-mails included invitations to attend conferences, sign up for webinars, submit articles, and/or serve on editorial staff for journals for which the receivers had no prior relationship or interest.

For the category of e-mails related to journals, we ascertained whether the journals associated with unsolicited e-mails were officially indexed or included in the following journal databases/resources: MEDLINE, PubMed, PubMed Central (PMC), Excerpta Medica database (EMBASE), Scopus Journal Citation Reports (JCR), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ), and Index Copernicus (summary description of these resources is in Table 1). For PMC, we distinguished between those journals that routinely deposit articles into PMC (termed PMC “Participating” journals) versus those that currently appear in PMC solely from author-initiated deposit of articles associated with work that has received National Institutes of Health (NIH) funding (termed PMC “Author Only” journals). These deposits would allow the author to comply with NIH Public Access Policy. PubMed Central Participating journals include NIH portfolio (journals that deposit all NIH-funded articles and possibly additional articles into PMC), selective deposit (journals that deposit a subset of articles into PMC and/or offer a hybrid open-access model), and full participation (all journal articles deposited in PMC). An important distinction between these broad categories is that PMC Author Only journals would otherwise not be included in the PMC (and more broadly PubMed) list of journals without author-initiated deposits, and a search for all articles in that journal in PubMed may yield only one or a small number of articles in the entire PubMed database (ie, vast majority of the journal content is not in PubMed).21 Note that some journals that ultimately become PMC participating journals and/or indexed in MEDLINE may be PMC Author Only journals for a period of time pending official inclusion. Inclusion of journals in databases/resources was checked at least 3 months after the e-mail receipt, allowing for catching journals in the process of being added to databases/resources at the time of the e-mail.

Table 1.

Journal Databases/Resources.

| Database | Approximate # of Unique Journals | Approximate # Records | Entity Maintaining Database/Resource | Comments | Hyperlink |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CINAHL | 5500 | 6 000 000 | EBSCO | One of multiple resources from EBSCO, CINAHL focuses on nursing/allied health resources. | https://health.ebsco.com/products/the-cinahl-database |

| EMBASE | 8500 | 32 000 000 | Elsevier (publisher) | Covers MEDLINE plus over 2000 other biomedical journals and also conference abstracts. | https://www.embase.com/login |

| Index Copernicus | 45 500 (6500 in more restrictive Journals Master List) | Not applicable | Index Copernicus International | Focus on non-English-language journals and qualitatively defined numeric rankings. | https://journals.indexcopernicus.com/ |

| DOAJ | 12 000 | 3 725 000 | Infrastructure Services for Open Access C.I.C. | Directory of Open Access Journals is an independently curated not-for-profit membership-based database. | https://doaj.org |

| Journal Citation Reports | 11 500 | 2 200 000 | Clarivate Analytics | Integrated with the subscription ISI Web of Science, source of proprietary Journal Impact Factor. | https://clarivate.com/products/journal-citation-reports/ |

| MEDLINE | 5200 | 25 000 000 | US NLM | Primary component of PubMed, made available to commercial suppliers. | https://www.nlm.nih.gov/bsd/medline.html |

| PubMed | 30 000 | 29 000 000 | US NLM | Produced by the NLM and freely available. Includes MEDLINE and PubMed Central. | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/ |

| PubMed Central | 7460 | 5 200 000 | US NLM | Subset of PubMed, number in second column includes only full participation, NIH portfolio, and selective deposit journals; does not include journals with only author-deposited articles. | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/ |

| Scopus | 22 800 | 71 000 000 | Elsevier | Also had independent board governing content. | https://www.elsevier.com/solutions/scopus |

Abbreviations: C.I.C., Community Interest Company; CINAHL, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; EMBASE, Excerpta Medica database; DOAJ, Directory of Open Access Journals; ISI, Institute for Scientific Information; NIH, National Institutes of Health; NLM, National Library of Medicine.

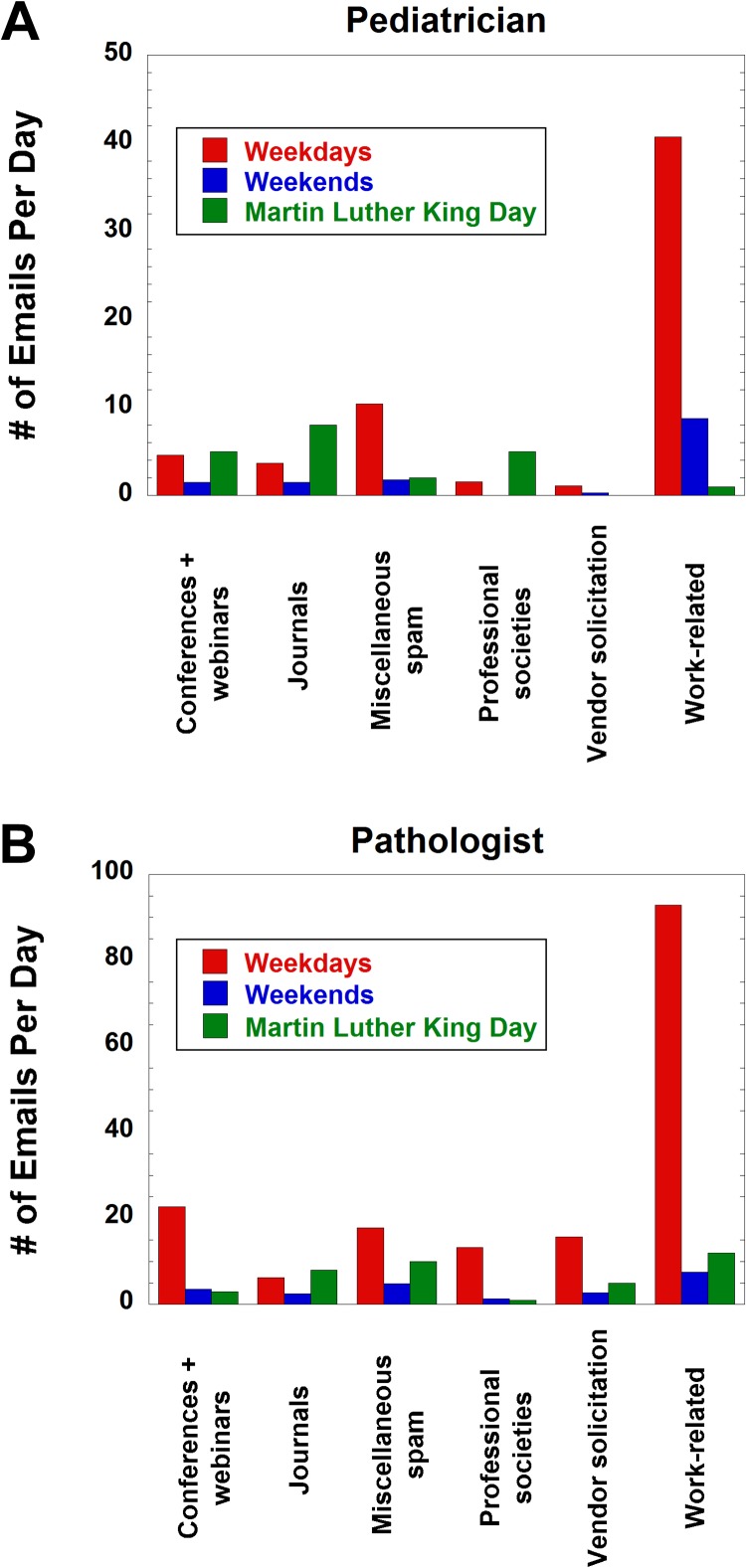

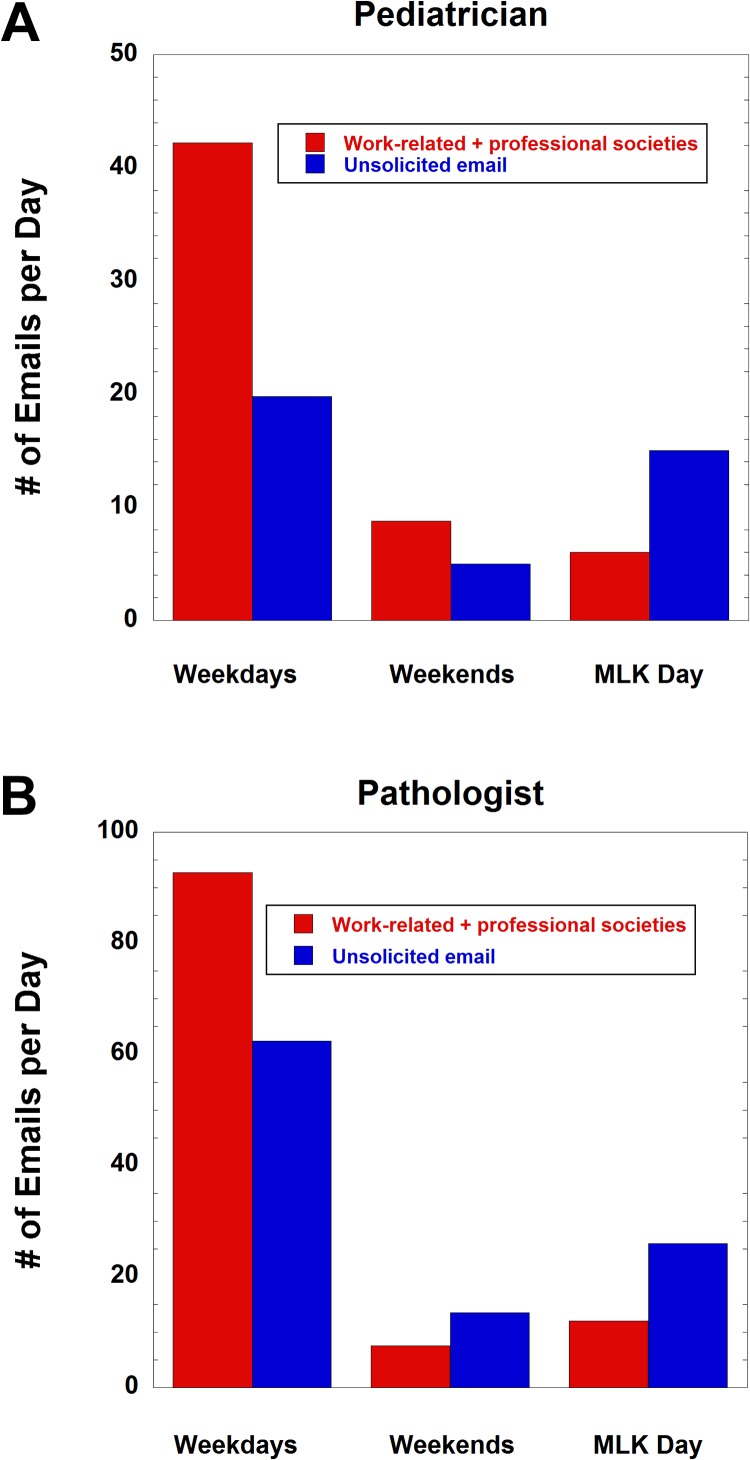

The pediatrician received 696 e-mails in the regular inbox during the 2-week time period, averaging 50 e-mails per day and an extrapolated annual total of 18 146. For the pediatrician, an additional 103 e-mails during the 2-week period were “prefiltered” to the junk folder using the institutional default spam/junk e-mail filter settings. The pathologist received 1581 e-mails in the regular inbox, averaging 113 e-mails per day and an extrapolated annual total of 41 219. For the pathologist, an additional 189 e-mails during the 2-week period were prefiltered to the junk folder using the institutional default spam/junk e-mail filter settings. Figure 1 breaks down e-mails received in the regular inbox of the pediatrician (Figure 1A) and pathologist (Figure 1B), sorted by categories and by day of week (weekdays, weekends, and the MLK holiday). Several notable trends are evident. Unsolicited e-mails from conferences/webinars and journals combined exceed that for professional societies regardless of time of week. Although work-related e-mails clearly comprise the majority of e-mails during weekdays, unsolicited e-mails are either close to or even exceed the volume of work-related e-mails during weekends and the MLK holiday. This is more clearly evident in Figure 2 that plots out solicited/work-related compared to unsolicited e-mails by time of week. For the pathologist, unsolicited e-mails comprised the majority of e-mails on weekends and the MLK holiday during the analysis time period (Figure 2B).

Figure 1.

Categorization of e-mails received in the regular e-mail inbox for the pediatrician (A) and pathologist (B).

Figure 2.

Comparison of solicited and unsolicited e-mails by time of week for the pediatrician (A) and pathologist (B).

Journal invitations accounted for most of the e-mail sorted by the institutional default spam filter settings into the Junk folder, with 54.4% for the pediatrician and 41.3% for the pathologist. Conferences/webinars (19.6% vs 9.7%) and vendors (22.8% vs 6.8%) constituted a higher percentage of all junk e-mails for the pathologist compared to the pediatrician. The estimated annual total of junk e-mails was 2685 for the pediatrician (7.4/day) and 4928 for the pathologist (13.5/day).

For unsolicited e-mails from journals, the pediatrician received 45 e-mails from 31 unique journals in the regular Inbox and 56 e-mails from 37 unique journals in the Junk folder, with a total of 68 unique journals across all e-mails. The pathologist received 75 e-mails from 53 unique journals in the regular Inbox and 78 e-mails from 60 unique journals in the Junk folder, with a total of 111 unique journals across all e-mails. Eighteen journals sent e-mails to both physicians.

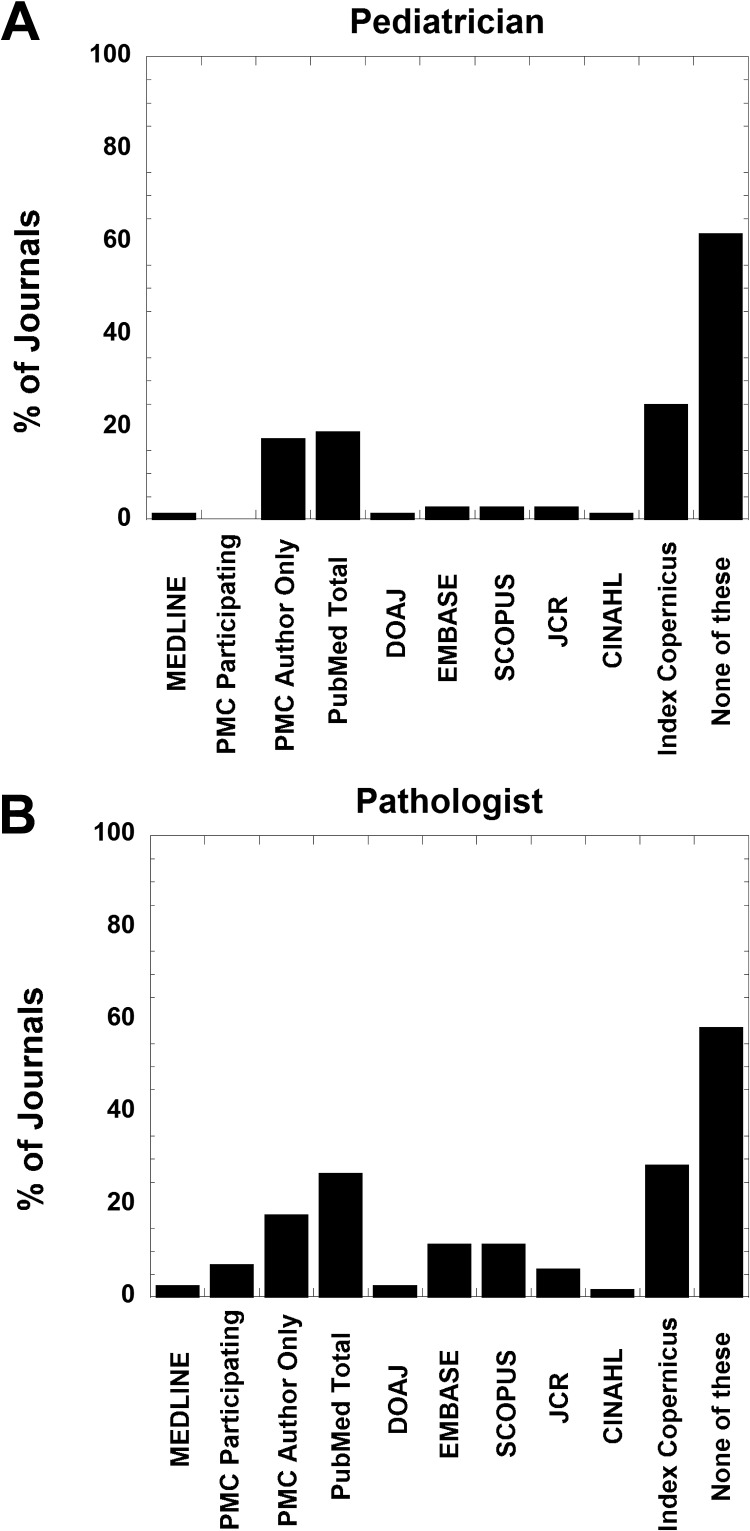

Most journals were found in none of the databases/resources in Table 1 (61.8% for the pediatrician; 58.6% for the pathologist). This number increased to 75.0% and 68.5% of the journals, respectively, if Index Copernicus was excluded. PubMed was the next most common database/journal, mostly accounted for by PMC Author Only journals, which accounted for 17.6% and 18.0%, respectively, for the pediatrician and pathologist (Figure 3). A total of 24 journals were found in only a single database/resource as a PMC Author Only journal. These 24 journals had an average of only 3.4 articles (standard deviation: 4.3; median: 1.5; range: 1-20) in the entire PubMed database, with 12 of the 24 journals having only a single author–deposited article in PMC. In contrast, 13 journals were PMC Participatory and/or indexed in MEDLINE. These 13 journals had an average of 6582 articles (standard deviation: 13 994; median: 1037; range: 12-51 610) in the entire PubMed database. With the exception of EMBASE and Scopus for the pathologist (11.7%), the journals were found at no higher than 7.2% in any other database/resource.

Figure 3.

Inclusion of journals from unsolicited e-mails to the pediatrician (A) and pathologist (B) in journal databases/resources. See Table 1 for detailed description of the databases/resources.

Overall, the default institutional e-mail junk/spam settings showed the highest effectiveness in identifying journal-related academic spam, with over half of total unsolicited journal e-mails prefiltered to the Junk folder (56/101 or 55.4% for pediatrician; 78/153 or 51.0% for pathologist) as opposed to going to regular Inbox. The rates prefiltered to the Junk folder were lower for unsolicited conference (10/53 or 18.9% for pediatrician; 37/115 or 32.2% for pathologist) and webinar e-mails (5/13 or 38.5% for pediatrician; 4/23 or 17.4% for pathologist). For both the pediatrician and pathologist in the 2 weeks, the default spam filter did not prefilter to the Junk folder any work-related e-mails or e-mails from societies or list serves to which either had intentionally joined. The default spam filter prefiltered approximately 30% of all other types of spam (25/85 or 29.4% for pediatrician; 27/82 or 32.9% for pathologist).

Academic Physicians and E-Mail Volumes

As demonstrated by our own 2-week analysis, academic physicians can receive a high volume of e-mail. Prior studies indicate that the volume correlates with higher academic rank, administrative duties, and publications.13,19,20 As such, e-mail may be an underrecognized contributor to a physician’s workload, especially as a physician advances in his or her career. This phenomenon can impact academic pathologists similarly to other academic physicians.19

The 2-week analysis of the coauthors’ e-mail reinforces that academic spam e-mail can account for a sizable fraction of total e-mail for academic physicians and is at least of a similar magnitude to more general and often more easily recognizable e-mail spam such as advanced fee, investment/financial, and romance scams. Unsolicited e-mails from journals and conferences are a major component of academic spam.11,13,19,20,22 One particular challenge with e-mails from journals and conferences is that these may get confused with non-spam e-mails related to the user’s actual scholarly activities and interests, including invitations to review articles for journals that are within the field of interest but not necessarily a journal frequently read by or familiar to the physician. Beyond the ever-present risk of overlooking internal work e-mails, a common fear cited in a survey of academicians regarding e-mails is of not wanting to miss a legitimate opportunity such as a genuine solicitation for writing a review article or serving on editorial or review board in a journal of interest to the recipient.13

The Specific Challenge of Journal E-Mails

Multiple studies have shown that e-mails from open-access, potentially predatory journals utilize a variety of tactics such as falsely claiming inclusion in databases, referencing bogus impact or citation factors, and giving journal names similar to established/more recognized journals.19,23-27 Claiming inclusion in MEDLINE, PubMed, and/or PMC are common claims (sometimes with vague language such as “some journals indexed in MEDLINE”) in unsolicited journal e-mails. As was evident in the limited 2-week analysis of the coauthors’ e-mails, journals in unsolicited e-mails typically have low rates of inclusion in databases/resources that have defined inclusion and exclusion criteria (eg, MEDLINE, PMC, CINAHL, DOAJ, EMBASE, JCR, and Scopus).19,23-28 Even for those found in PMC and PubMed, many journals associated with unsolicited e-mails are found in PMC solely due to author-initiated deposits of NIH-funded research. This pathway, which allows a journal to be in the PMC database of journals even with only a single author-initiated article deposit, has been identified as a means for potentially low-quality journals to be included in the broader PMC database.29 It is important to point out, however, that PMC Author Only status is a common temporary state for journals that ultimately become PMC Participatory, given that the required process for full inclusion requires formal review and time for the journal to accrue content.

A detailed analysis of journals with potentially predatory characteristics found that promotion of Index Copernicus and its associated Index Copernicus Value (ICV) was a common claim.27 We have not found any detailed analysis of the contents of this index in the published literature. In the 2 weeks of e-mails analyzed by the coauthors, Index Copernicus was the most common database resource to include the journals in the unsolicited e-mails. Index Copernicus contains 2 main collections of journals. The broader Index Copernicus International (ICI) World of Journals contains over 45 000 scientific journals, including many high-impact biomedical journals. The process to join this broader index is free and simply requires registration by the journal publisher. A more restrictive ICI Journals Master Lists (approximately 6500 journals) requires review by ICI in addition to publisher registration.30 A subset of journals in the Masters Lists are assigned an ICV based on factors such as “cooperation,” “digitization,” and “internationalization,” as opposed to the more traditional impact factor metric based on citation of articles in the journal by other publications, an example being the Journal Impact Factors by Clarivate Analytics. The validity of the ICV as an “impact factor” is not clear, and potential authors should be aware of other databases/resources for assessing journals and publication impact metrics.27

Tools for Managing Spam E-Mail

According to productivity experts, while e-mail may be a threat to efficiency, it also is currently an essential work tool.31 Business strategies used to manage e-mail include limiting access, inbox management, and e-mail etiquette.32 Research has shown that limiting employees’ access to e-mail resulted in improved focus on tasks, less multitasking, and reduced stress. One study showed limiting logins to 3 times daily decreased the time necessary to process e-mails by almost 20%33; however, one challenge in the health-care sector is that limited logins will not be viable if the expectation is rapid e-mail response. This strategy would only be realistic for those whose job tasks do not require quick e-mail responses.

Unsubscribing from distribution lists is frequently recommended though effectiveness may be limited, particularly since unscrupulous senders may ignore the requests or even use them as verification that a target e-mail address is valid. One study showed that unsubscribing decreased academic spam invitations to conferences and journals by 39% after 1 month but only 19% after 1 year.22 An alternative strategy is to block specific e-mail addresses or subdomains or divert them into the Junk or another specific folder. For some e-mail software, blocking a specific sender can be done very quickly. One challenge is that the sheer number of unsolicited journal e-mails in the Junk folder make it difficult to identify work/solicited e-mails that get routed to the Junk folder. Our limited 2-week analysis period did illustrate that the institutional default e-mail filter did prefilter slightly over half of unsolicited journal e-mails to the Junk folder. This helps considerably in cutting down the burden landing in the regular Inbox. The rates of prefiltering were lower for other categories of academic e-mail spam, ranging from 17.4% to 38.5% for unsolicited e-mails from conferences and for webinars. Thus, there is opportunity to improve default e-mail filters to identify even more academic spam e-mail.

Rules can be customized so that incoming e-mails with specific phrases are filtered to a specific inbox folder to decrease inbox clutter and more quickly identify higher priority messages. A main challenge with academic spam e-mails is their use of common spam tactics such as obscuring country or sender of origin, frequent changing of e-mail address, and the sheer number of different entities sending out the e-mails.19,25,34 The pediatrician and pathologist coauthors received e-mails from 68 and 111 unique journals, respectively, in only a 2-week period. One positive finding was that the institutional Junk mail filter using default settings effectively identified many unsolicited journal e-mails, as these comprised the major category of e-mails in the Junk folder for both the pediatrician and pathologist. In addition, a number of journals sent multiple e-mails by the same sender just in the 2-week period. Thus, the strategy of blocking specific senders would have shown some benefit even within 2 weeks.

General Practices for Information Overload

Practicing e-mail etiquette such as removing unnecessary recipients, sparingly using reply all, and limiting e-mail length decreases e-mail burden for others and may change their practices.31,32 An e-mail etiquette study of Orthopedic resident physicians found that participants were 2.5 times more likely to respond immediately to e-mails they perceived as favorable.35 Senders who used colored backgrounds, difficult to read font, no subject header, and/or lacked a personalized greeting were perceived as inefficient, unprofessional, and irritating. E-mail is best suited for straightforward questions or notifications. Complicated issues and/or negotiations are often better handled in real time such as a phone call or face-to-face meeting to avoid numerous back-and-forth e-mails about the same topic.31,32

In addition to e-mail, other forms of electronic communication can also contribute to overload. At our own institution, this includes but is not limited to phone secure messaging (frequently used by the pediatrician for work-related voice and text communication both within and outside of the hospital), electronic medical record (EMR), staff messaging (frequently used by both physicians and a common route for the pathologist to receive clinician queries/complaints and select patient complaints related to laboratory testing), messages from the EMR patient portal (Epic MyChart), and message and pages from 1-way pagers. Institutions have also begun to use EMR inpatient portals (eg, for patients to send nonurgent questions to the care team).36,37

Summary

In conclusion, academic physicians can receive a high volume of unsolicited e-mails. Although the overall majority of e-mails are work-related, the contribution from academic spam especially from invitations from low-quality journals and conferences is significant. Physicians and institutions should develop strategies to optimize e-mail communication and management with focus on minimizing the volume of unsolicited e-mails. Education of academic physicians and trainees should include discussion of management of time spent on e-mails and other electronic communication, assessment of journal quality, characteristics of potentially predatory journals, and scholarly database/resources.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Dr Wood has a financial relationship with McGraw Hill Professionals. She receives royalties for a pediatric board review textbook she coedited. The work presented was not influenced by that relationship. Dr Krasowski has no financial disclosures to report.

ORCID iD: Matthew D. Krasowski  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0856-8402

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0856-8402

References

- 1. The Physicians Foundation. 2016 Survey of America’s Physicians: Practice Patterns and Perspectives Web Page. 2016. https://physiciansfoundation.org/research-insights/physician-survey/. Accessed September 19, 2019.

- 2. Rao SK, Kimball AB, Lehrhoff SR, et al. The impact of administrative burden on academic physicians: results of a hospital-wide physician survey. Acad Med. 2017;92:237–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU. Administrative work consumes one-sixth of U.S. physicians’ working hours and lowers their career satisfaction. Int J Health Serv. 2014;44:635–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kane L. National Physician Burnout, Depression & Suicide Report Web Page 2019. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-lifestyle-burnout-depression-6011056. Accessed September 19, 2019.

- 5. Whittaker S, Sidner C. Email overload: exploring personal information management of email. In: Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada: SIGCHI; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Reinke K, Chamorro-Premuzic T. When email use gets out of control: understanding the relationship between personality and email overload and their impact on burnout and work engagement. Comput Hum Behav. 2014;36:502–509. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Healthcare Client Services. Professional Use of Smartphones by Doctors in 2015 Web Page 2015. https://www.kantarmedia.com/us/thinking-and-resources/blog/professional-usage-of-smartphones-by-doctors-in-2015. Accessed September 19, 2019.

- 8. Gombert L, Konze AK, Rivkin W, Schmidt KH. Protect your sleep when work is calling: how work-related smartphone use during non-work time and sleep quality impact next-day self-control processes at work. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:E1757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rod NH, Dissing AS, Clark A, Gerds TA, Lund R. Overnight smartphone use: a new public health challenge? A novel study design based on high-resolution smartphone data. PLoS One. 2018;13: e0204811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Elhai JD, Levine JC, Hall BJ. The relationship between anxiety symptom severity and problematic smartphone use: a review of the literature and conceptual frameworks. J Anxiety Disord. 2019;62:45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Clemons M, de Costa ESM, Joy AA, et al. Predatory invitations from journals: more than just a nuisance? Oncologist. 2017;22:236–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Paul IM, Levi BH. Metastasis of e-mail at an academic medical center. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168:290–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wilkinson TA, Russell CJ, Bennett WE, Cheng ER, Carroll AE. A cross-sectional study of predatory publishing emails received by career development grant awardees. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e027928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bartholomew RE. Science for sale: the rise of predatory journals. J R Soc Med. 2014;107:384–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bowman DE, Wallace MB. Predatory journals: a serious complication in the scholarly publishing landscape. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;87:273–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bowman JD. Predatory publishing, questionable peer review, and fraudulent conferences. Am J Pharm Educ. 2014;78:176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Harvey HB, Weinstein DF. Predatory publishing: an emerging threat to the medical literature. Acad Med. 2017;92:150–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Moher D, Srivastava A. You are invited to submit. BMC Med. 2015;13:180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Krasowski MD, Lawrence JC, Briggs AS, Ford BA. Burden and characteristics of unsolicited emails from medical/scientific journals, conferences, and webinars to faculty and trainees at an academic pathology department. J Pathol Inform. 2019;10:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mercier E, Tardif PA, Moore L, Le Sage N, Cameron PA. Invitations received from potential predatory publishers and fraudulent conferences: a 12-month early-career researcher experience. Postgrad Med J. 2018;94:104–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Manca A, Cugusi L, Dragone D, Deriu F. Predatory journals: prevention better than cure? J Neurol Sci. 2016;370:161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Grey A, Bolland MJ, Dalbeth N, Gamble G, Sadler L. We read spam a lot: prospective cohort study of unsolicited and unwanted academic invitations. BMJ. 2016;355:i5383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Andoohgin Shahri M, Jazi MD, Borchardt G, Dadkhah M. Detecting hijacked journals by using classification algorithms. Sci Eng Ethics. 2018;24:655–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bolshete P. Analysis of thirteen predatory publishers: a trap for eager-to-publish researchers. Curr Med Res Opin. 2018;34:157–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dadkhah M, Maliszewski T, Jazi MD. Characteristics of hijacked journals and predatory publishers: our observations in the academic world. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2016;37:415–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dadkhah M, Maliszewski T, Teixeira da Silva JA. Hijacked journals, hijacked web-sites, journal phishing, misleading metrics, and predatory publishing: actual and potential threats to academic integrity and publishing ethics. Forensic Sci Med Pathol. 2016;12:353–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shamseer L, Moher D, Maduekwe O, et al. Potential predatory and legitimate biomedical journals: can you tell the difference? A cross-sectional comparison. BMC Med. 2017;15:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dadkhah M, Lagzian M, Borchardt G. Questionable papers in citation databases as an issue for literature review. J Cell Commun Signal. 2017;11:181–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Manca A, Moher D, Cugusi L, Dvir Z, Deriu F. How predatory journals leak into PubMed. Can Med Assoc J. 2018;190:E1042–E1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Index Copernicus. ICI Journals Master List Web Page 2019. https://journals.indexcopernicus.com/. Accessed September 19, 2019.

- 31. Gallo A. Stop email overload Brighton, MA: Harvard Business Review; February 12, 2012. https://hbr.org/2012/02/stop-email-overload-1. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Armstrong MJ. Improving email strategies to target stress and productivity in clinical practice. Neurol Clin Pract. 2017;7:512–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kushlev K, Dunn EK. Stop checking email so often New York, NY: New York Times; January 9, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lewinski AA, Oermann MH. Characteristics of E-mail solicitations from predatory nursing journals and publishers. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2018;49:171–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Resendes S, Ramanan T, Park A, Petrisor B, Bhandari M. Send it: study of e-mail etiquette and notions from doctors in training. J Surg Educ. 2012;69:393–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. McAlearney AS, Sieck CJ, Hefner JL, et al. High touch and high tech (HT2) proposal: transforming patient engagement throughout the continuum of care by engaging patients with portal technology at the bedside. JMIR Res Protoc. 2016;5:e221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Winstanley EL, Burtchin M, Zhang Y, et al. Inpatient experiences with MyChart bedside. Telemed J E Health. 2017;23:691–693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]