Abstract

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a rare hematological disorder characterized by local or generalized, uncontrolled proliferation and infiltration of Langerhans type of histiocytic cells. It represents a spectrum of clinicopathologic disorders, ranging from a highly aggressive and frequently fatal multisystem disease to an easily cured solitary lesion of bone. Involvement of children and the younger age group is more common than the adults. Oral cavity involvement occurs early in LCH, but the initial symptoms are generally nonspecific, often causing misdiagnosis. This report describes a rare case of chronic localized LCH in an adult patient, with involvement of oral cavity. A 34-year-old male patient presented with multiple nodulo-papular, ulcerated lesions in gingiva involving both the jaws (primarily mandible) and the left buccal mucosa, in addition to regional teeth mobility. The most striking feature was that even after extraction of mobile teeth, the lesions persisted. After recording proper history, performing clinical and radiological evaluation, an incisional biopsy was performed followed by histopathology and immunohistochemistry to reach a confirmatory diagnosis of LCH, thereby implementing early and appropriate initiation of treatment.

Keywords: Eosinophilic granuloma, histiocytosis X, Langerhans cell, oral mucosa

Introduction

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH), previously known as histiocytosis X, is an uncommon hematological disorder characterized by uncontrolled, local, or generalized stimulation, proliferation, and infiltration of Langerhans type of histiocytic cells. Its clinical presentation varies from a highly destructive and lethal multisystem disease to an easily cured unifocal lesion of bone.[1] It affects 4–8 children/million and 1–2 adults/million each year (according to the Histiocytosis Association), with a 10%–20% mortality rate.[2,3] LCH has no bias for race and has a predilection for males.[4,5] The intensity of LCH is usually age related, because diffuse multisystem involvement with a poor prognosis occurs in early childhood, multifocal single-system disease is observed in children aged up to 5 years, and unifocal bone-limited disease affects the elder children.[6]

Normally, three types of LCH are recognized: chronic localized form called eosinophilic granuloma (60%–70% of all LCH cases), characterized by localized, monostotic, or polyostotic bone lesions with occasional extraskeletal (but not visceral) involvement, common in older children and young adults; the chronic disseminated form, known as Hand–Schuller–Christian disease which includes a classic triad of skull lesions, exophthalmos, and diabetes insipidus with more prevalence in younger children; and the third type called Letterer–Siwe disease, an acute disseminated form, especially occurring in infants under 2 years of age, affecting multiple organs, and including signs such as hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, bone lesions, and skin rash, along with pancytopenia, thereby having a poor prognosis.[2,6,7] Bones commonly involved in LCH are skull bones (orbital, temporal bone, and sphenoid), jaws, long bones, ribs, vertebra, and pelvis.[3,8]

Oral cavity involvement occurs early, but the initial symptoms are usually nonspecific, causing misdiagnosis.[8] The maxilla and mandible may be affected in LCH (mandible:Maxilla = 2:1), both with and without systemic involvement. Jaw lesions may present with dull pain, regional teeth mobility, along with jaw expansion.[2,8] Oral mucosal involvement may develop if the disease breaks out of bone and is characterized by gingival inflammation, ovoid or round ulcerated lesions, destruction of the keratinized gingiva, gingival hypertrophy, formation of periodontal pockets, mobility of teeth, alveolar bone expansion, and ulcers of the buccal mucosa, palate, and tongue.[3]

Radiologically, the lesions are observed as sharply punched out radiolucencies without a well-corticated margin or may appear as ill-defined radiolucencies. Extensive alveolar bone loss around the teeth gives a “tooth floating in air” appearance.[9] Well-circumscribed, punched out lesions in skull or other parts of skeleton may also be observed.[10,11]

Histopathology reveals a sheet-like proliferation of pale-staining Langerhans cells, with abundant cytoplasm, indistinct cell borders, rounded or indented “coffee-bean-” shaped vesicular nuclei, and absence of mitotic activity.[3] Eosinophils predominate among the inflammatory infiltrate, which helps differentiate LCH from common periapical and periodontal lesions of the jaw. All three types of LCH have similar histopathological findings. Immunohistochemical staining for CD1a, CD207, CD68, and S100 antibody is confirmative for LCH.[2]

This report describes a rare case of chronic localized variant of LCH in an adult patient, with soft and hard tissue involvement of oral cavity, and reflects the importance of integration of clinical and radiological examinations, followed by histopathology and immunohistochemistry to reach a correct diagnosis.

Case Report

A 34-year-old male patient from semi-urban area reported to the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, Guru Nanak Institute of Dental Sciences and Research, Kolkata, with a complaint of recurrent painless episodes of gingival swelling and ulceration, associated with discharge of pus from certain areas of gingival crevice, increased mobility of regional teeth involving the lower jaw, for the last 2–3 years.

Medical history was noncontributory. The patient was not under any medications. Due to increased mobility of teeth and poor periodontal condition, he underwent extraction of teeth 26, 27, 28, 31, 41, 42, 43, 44, and 45 by a private dentist. Despite the extractions, the symptoms of gingival swelling and ulceration never resolved completely.

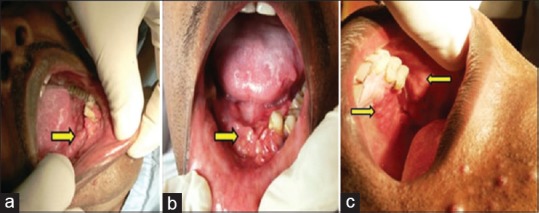

On general examination, the patient was healthy and moderately built. No significant systemic manifestations or extraoral involvement were noted. Intraoral examination revealed multiple nodulo-papular, ulcerated lesions in gingiva involving entire mandibular arch and left posterior maxillary arch, along with regional teeth mobility (second and third degree) in the same areas [Figure 1a–c]. Few medium-sized, nodulo-papular growths were also observed in the posterosuperior aspect of the left buccal mucosa [Figure 1c]. The most striking feature was, that even after extraction of mobile teeth, the regional gingiva retained its enlarged, ulcerated, and nodular appearance. Oral hygiene of the patient was very poor, along with halitosis.

Figure 1.

(a-c) Multiple nodulo-papular, ulcerated lesions in gingiva involving the entire mandibular arch, gingiva of left posterior maxillary arch in relation to the premolars and molars along with similar lesions in the posterosuperior aspect of the left buccal mucosa (yellow arrows)

Orthopantomogram revealed severe generalized irregular alveolar bone destruction in the entire mandibular and in the left posterior maxillary alveolar ridge region [Figure 2]. Posteroanterior (PA) view radiograph of chest showed no abnormality.

Figure 2.

Orthopantomogram showing severe generalized irregular alveolar bone destruction in the entire mandibular and in the left posterior maxillary alveolar ridge region

Complete blood laboratory tests were within normal limits. Preoperative serology was nonreactive. Based on the above clinical and radiological findings, the case was provisionally diagnosed as chronic generalized aggressive periodontitis. After taking consent from the patient, an incisional biopsy was performed from the representative site of the lesion under local anesthesia.

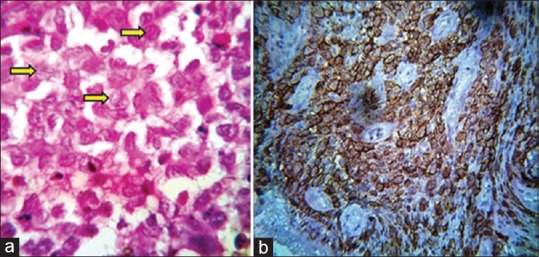

Routine hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections revealed a fibrovascular connective tissue, which was intensely infiltrated with chronic inflammatory cells, chiefly composed of eosinophils and plasma cells. The most striking feature was the presence of sheet-like proliferation of large mononuclear pale-staining cells with ill-defined cellular margins and a deep groove in the nucleus, mimicking a “coffee-bean” appearance. These cells characteristically resembled Langerhans cells [Figure 3a]. After considering the microscopic features, a diagnosis of “LCH” was made, but to confirm our diagnosis, immunohistochemistry was performed which showed immunopositivity for CD1a antibody [Figure 3b].

Figure 3.

(a) The presence of sheet-like proliferation of Langerhans cells, having coffee bean-shaped appearance, eosinophils, and plasma cells (H and E, ×100). (b) Langerhans cells exhibiting positivity for anti-CD1a (×40)

Based on these findings, the case was finally diagnosed as “LCH.” Due to poor economic condition, the patient was referred to the state medical hospital to evaluate the extent of the disease and for necessary management.

Discussion

The term histiocytosis X was originally proposed by Lichtenstein in 1953, which is currently known as LCH. Langerhans cells are dendritic mononuclear cells normally found in the epidermis, mucosa, lymph nodes, and bone marrow. Their normal function is to process and present antigens to T-lymphocytes. LCH represents a collective term for a spectrum of rare clinicopathologic disorders, characterized by monoclonal proliferation and infiltration of Langerhans type of histiocytic cells, leading to hard and soft tissue destruction.[8,12] Despite improved knowledge on its clinical presentation, disease progress, and its molecular profiling, the etiology and pathogenesis of LCH is still a subject of controversy.[1] A review of literature suggests that LCH cells are clonal and a cancer-associated mutation (BRAFV600E) is responsible for its occurrence, indicating that LCH may be more of a neoplastic (but not a malignant) disease, rather than a reactive disorder.[2]

Oral manifestations are the earliest manifestations seen in around 5% to 75% of patients suffering from LCH.[8] The patient under discussion was a 34-year-old male patient with involvement of oral hard and soft tissues. Intraoral examination revealed multiple, nodulo-papular, ulcerated gingival lesions, involving both the jaws (primarily mandible), along with regional teeth mobility. Similar lesions were also observed in the posterosuperior aspect of the left buccal mucosa. No significant medical history, systemic disease, or lymphadenopathy was present. These clinical findings are consistent with the observations reported by authors of different studies.[3,8]

The conventional radiological findings observed in LCH are due to destruction of bone by Langerhans cells. Involvement of the alveolar bone leads to a “tooth floating in air” appearance, causing tooth mobility and displacement, thereby mimicking the appearance of periodontitis. Tooth mobility and displacement due to irregular alveolar bone destruction was also present in our case. However, the typical “tooth floating in air” appearance was absent. Our provisional diagnosis included chronic generalized aggressive periodontitis. Since there are no pathognomonic clinical and radiographic features of LCH, diagnosis is made on the basis of histopathological and immunohistochemical basis.

Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections revealed the presence of diffuse infiltration of Langerhans cells, along with variable numbers of eosinophils, lymphocytes, and plasma cells, which was suggestive of LCH. The histopathology of LCH is similar in all its three variants, except in the acute disseminated subtype which resembles acute form of lymphomas. Confirmatory diagnosis was made by immunohistochemical analysis, which revealed positivity for antibodies directed against CD1a antigen, present on the Langerhans cell surface.

After the diagnosis of LCH has been established, a complete physical and hematological examination along with liver function tests, urine osmolality, bone marrow examination, complete skeletal radiographic survey, and chest radiography is necessary to check for multiorgan involvement.[12]

Management of LCH is a controversial topic, due to its varied clinical presentation, and absence of proper diagnostic and treatment criteria. It depends on various factors such as age of the patient and single or multisystem involvement, along with the sites involved. Since oral manifestations are the first observable presentation (in most of the cases), the dental surgeon has a very important role to play in its initial diagnosis and treatment of the oral symptoms. Systemic symptoms should be dealt by the specific specialist. Localized and accessible oral lesions in the jaws are treated by surgical curettage or excision. Inaccessible lesions can be subjected to low-dose radiotherapy, but not very effective, especially in young patients, due to chances of secondary malignancy. Intralesional corticosteroids (e.g., prednisolone 20–30 mg/day for 2–4 weeks and then followed by tapering of the dose) may be administered in some localized lesions. Chemotherapy indicated for multiorgan involvement.[8,13] Our patient was referred to the state medical hospital due to his poor socioeconomic status, but unfortunately, we lost him for follow-ups.

The International Registry of the Histiocyte Society on Adult LCH (IRHSA) has reviewed the clinical presentations of 274 cases from 13 nations, and they reported that the probability of survival at 5 years postdiagnosis was 92.3% overall, 100% for patients with single-system disease, 87.8% for isolated pulmonary disease, and 91.7% for multisystem disease. Hence, the number of organs affected is intimately related with the prognosis of the disease. In case of multisystem involvement, reactivation in adults may occur in about 25%–38% of cases.[3]

Conclusions

LCH is rare neoplasm of the immune system which is frequently misdiagnosed. Importance of reporting such cases lies in the fact that oral lesions may be the earliest manifestations of LCH and, in many cases, the only site that may be involved. It should be kept in mind that oral cavity is often the indicator of systemic diseases. We present a case of LCH with late-onset, localized involvement of jaw bones, in an adult patient suffering for the last 2–3 years. Our case is an example of another rare report which proves that LCH is not only confined to the pediatric age group but also occur in adults. An integration of recording proper clinical history and performing adequate investigative procedures will help establish early diagnosis and implement proper therapeutic modalities to provide cure in most cases.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Dr. Ranjan Rashmi Paul, Deputy Director-cum-In-charge, Research and Development, GNIDSR, Kolkata, West Bengal, India, and the entire faculty and staff of the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, Guru Nanak Institute of Dental Sciences and Research, for their valuable guidance and help in every aspect.

References

- 1.Shevale VV, Ekta K, Snehal T, Geetanjal M. A rare occurrence of Langerhans cell histiocytosis in an adult. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2014;18:415–9. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.151335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel R, Shahane A. The epidemiology of Sjögren's syndrome. Clin Epidemiol. 2014;6:247–55. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S47399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Facciolo MT, Riva F, Gallenzi P, Patini R, Gaglioti D. A rare case of oral multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Clin Exp Dent. 2017;9:e820–4. doi: 10.4317/jced.53774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atri R, Dhankhar R, Dhull AK, Nair VJ, Kaushal V. Alveolar Langerhans cell histocytosis – A case report. J Oral Health Community Dent. 2008;2:16–8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aricò M, Girschikofsky M, Généreau T, Klersy C, McClain K, Grois N, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in adults. Report from the International Registry of the Histiocyte Society. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:2341–8. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(03)00672-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rizzo FM, Cives M, Simone V, Silvestris F. New insights into the molecular pathogenesis of Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Oncologist. 2014;19:151–63. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shi S, Liu Y, Fu T, Li X, Zhao S. Multifocal Langerhans cell histiocytosis in an adult with a pathological fracture of the mandible and spontaneous malunion: A case report. Oncol Lett. 2014;8:1075–9. doi: 10.3892/ol.2014.2272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rao DG, Trivedi MV, Havale R, Shrutha SP. A rare and unusual case report of Langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2017;21:140–4. doi: 10.4103/jomfp.JOMFP_10_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neville BW, Damn DD, Allen CM, Bouquot JE. Hematologic disorders. In: Alvis K, editor. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: W. B. Saunders Company; 2002. pp. 513–4. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Regezi JA, Sciubba JJ, Jordan RC. Benign nonodontogenic tumors. In: Dolan J, editor. Oral Pathology: Clinical Pathologic Correlations. 6th ed. St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier Publishers; 2012. pp. 307–10. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sapp JP, Eversole LR, Wysocki GP. Bone lesions. In: Alvis K, editor. Contemporary Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. 2nd ed. St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier Publishers; 2004. pp. 125–6. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumar YP, Agrawal J, Mohanlakshmi J, Kumar PS. Langerhans cell histiocytosis revisited: Case report with review. Contemp Clin Dent. 2015;6:432–6. doi: 10.4103/0976-237X.161912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marx RE, Stern D. Neoplasms of the immune system. In: Bywaters LC, editor. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology – A Rationale for Diagnosis and Treatment. 1st ed. Carol Stream, Illinois: Quintessence Publishers, Inc.; 2003. pp. 871–4. [Google Scholar]