Abstract

Background

Gastric subepithelial lesions, including gastrointestinal stromal tumors, are often found during routine gastroscopy. While endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy (EUS-FNAB) has been the gold standard for diagnosing gastric subepithelial lesions, alternative open biopsy procedures, such as mucosal incision-assisted biopsy (MIAB) has been reported useful. The aim of this study is to evaluate the efficacy of MIAB for the diagnosis of gastric SELs compared with EUS-FNAB.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed medical records of 177 consecutive patients with gastric SELs who underwent either MIAB or EUS-FNAB at five hospitals in Japan between January 2010 and January 2018. Diagnostic yield, procedural time, and adverse event rates for the two procedures were evaluated before and after propensity-score matching.

Results

No major procedure-related adverse events were observed in either group. Both procedures yielded highly-accurate diagnoses once large enough samples were obtained; however, such successful sampling was more often accomplished by MIAB than by EUS-FNAB, especially for small SELs. As a result, MIAB provided better diagnostic yields for SELs smaller than 20-mm diameter. The diagnostic yields of both procedures were comparable for SELs larger than 20-mm diameter; however, MIAB required significantly longer procedural time (approximately 13 min) compared with EUS-FNAB.

Conclusions

Although MIAB required longer procedural time, it outperformed EUS-FNAB when diagnosing gastric SELs smaller than 20-mm diameter.

Keywords: Subepithelial lesion, Mucosal incision-assisted biopsy, Ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy

Background

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) and leiomyomas are the most common types of gastric subepithelial lesions (SELs) [1–3]. Many guidelines recommend histological evaluation of gastric SELs that have characteristics suggestive of GISTs [4–6]. Although endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy (EUS-FNAB) has been the gold standard for such evaluation, obtaining large enough samples for histological analyses by using this technique is sometimes difficult, even with the recently-developed FNB needles and forward-viewing endoscopes.

Alternatively, “open biopsy” of SELs can be performed by partially removing the covering mucosa and exposing the lesion. Since the development of endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) for gastrointestinal neoplasms, ESD knives have increasingly been used to perform open biopsies of SELs [7–9]. We have named this biopsy technique, which was originally reported by Lee et al., [9] but which did not have a specific name, mucosal incision-assisted biopsy (MIAB) [10]. Our previous study suggested that MIAB is useful for SELs with intraluminal, but not extraluminal, growth patterns [11]. Our more recent study [11] suggested that MIAB and EUS-FNAB are of comparable usefulness for diagnosing SELs; however, the number of patients enrolled in that study (23 patients in MIAB group) was too small to enable evaluation of the efficacy of MIAB for SELs of differing sizes. Thus, in the current study, we collected medical records of a larger number of patients with SELs with intraluminal growth patterns and compared the usefulness, diagnostic yield, procedural time, and associated adverse events of MIAB and EUS-FNAB.

Methods

Patients

This was a retrospective comparative analysis of MIAB and EUS-FNAB using data for patients with gastric SELs with intraluminal growth patterns who underwent either MIAB or EUS-FNAB at five hospitals in Japan (Kyushu University Hospital, Kyushu Medical Center, Harasanshin Hospital, Kyushu Rosai Hospital, and Kitakyushu Municipal Medical Center) between January 2010 and January 2018. No patients who met the above criteria were excluded from the study. The decision to use MIAB or EUS-FNAB was left to the primary physician for each patient.

The intraluminal growth pattern of the SELs was confirmed by preoperative gastroscopy and EUS, and SEL size was measured on EUS images. All patients who underwent biopsy (either MIAB or EUS-FNAB) were suspected before biopsy of having tumors of mesenchymal origin, such as GISTs, leiomyomas, schwannomas, and glomus tumor, on the basis of EUS findings.

MIAB and EUS-FNAB procedures

For MIAB, to lift the mucosa covering the SEL and to create a safer incision, normal saline or glycerol supplemented with diluted epinephrine was injected into the submucosal layer above the lesion. The target mucosal and submucosal tissues were incised with an endoscopic submucosal dissection knife (Needle knife, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan; Flush knife, Fuji Film, Tokyo, Japan) using electrosurgical current generated by a high-frequency power supply (ICC or VIO300D; ERBE, Tubingen, Germany). After exposing the lesion, tissue samples were obtained by biopsy forceps (Radial jaw, Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA). Approximately 3–7 biopsy samples were obtained from each lesion.

For EUS-FNAB, 19- to 25-gauge FNAB needles (described later) were used to obtain SEL samples through the mucosa under the guidance of oblique-view EUS imaging (GF-UCT 260; Olympus). Rapid on-site evaluation (ROSE) by cytologists or pathologists was performed for all EUS-FNAB procedures. Half of each FNAB sample was used for ROSE and the other half reserved for later histological examination. The procedures were repeated a maximum of six times until either the biopsy team considered they had obtained enough samples for histology, for example, because the cytologists/pathologists had seen numerous spindle cells, indicating that the needle had reached a GIST, or the team decided to end the procedure due to difficulties in sample collection.

All samples in both groups were later evaluated histologically by pathologists. All patients were monitored daily for symptoms and signs of hematomesis and hematochezia.

Comparison between MIAB and EUS-FNAB

Three aspects of MIAB and EUS-FNAB were compared: diagnostic yield, procedural time, and adverse event rate. The procedural time was defined as the time from start to finish of the biopsy procedures. The data were collected from the operational records of patients. Major bleeding was defined as a ≥ 2 g/dL drop in blood hemoglobin.

Comparison between EUS-FNA and EUS-FNB

The following needles were categorized as FNA and FNB needles: FNA; SonoTip, Mediglobe GmbH, Rosenheim, Germany; Expect, Boston Scientific; Ez-shot, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan; and FNB: Echo-Tip Procore, Cook Medical, Bloomington, USA; Acquire, Boston Scientific. The diagnostic yields achieved by FNA and FNB needles were compared.

Statistical analysis

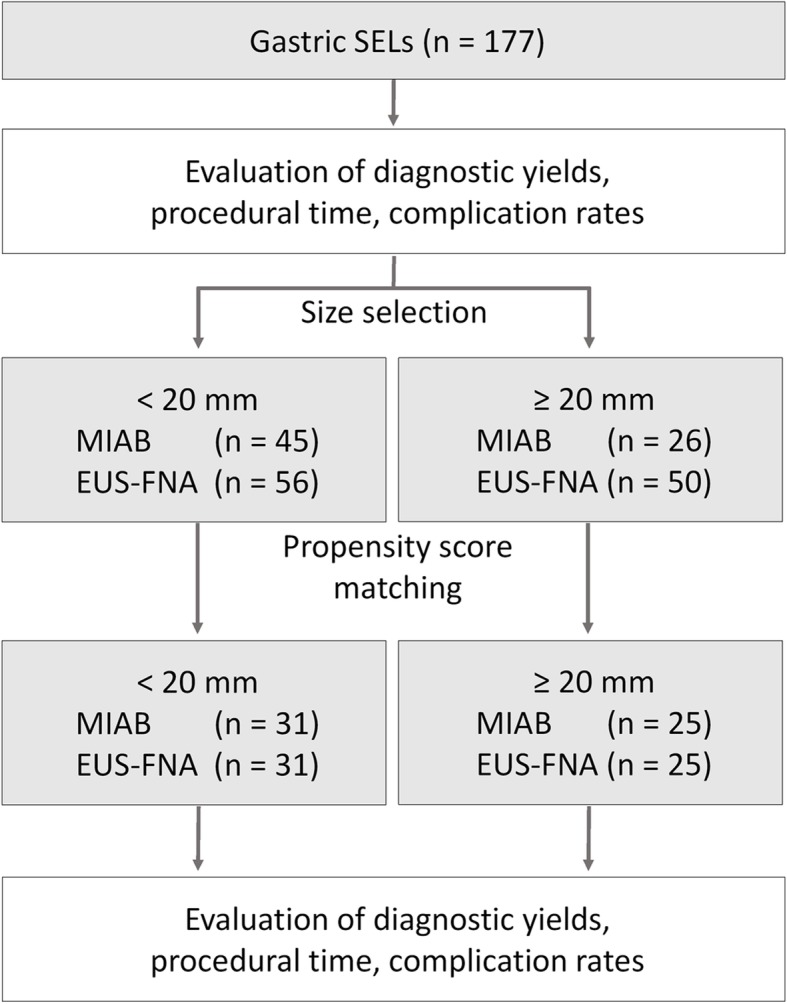

All statistical analyses were performed using the JMP software program version 13.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Comparisons between MIAB and EUS-FNAB were performed before and after propensity-score matching of the lesion sizes in the two groups (Fig. 1). The chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test were used to compare the categorical data (patients’ characteristics, lesion locations, and histology types). Student’s t-test was used to compare continuous data (age, lesion size, and procedural time) before propensity-score matching. We used a multivariate logistic regression analysis to evaluate the relationship between the diagnostic yield and lesion size. After propensity-score matching, Student’s paired t-test was used to compare continuous data in the two groups. P < 0.05 indicated statistical significance, for all tests.

Fig. 1.

Summary of the study protocol

To estimate propensity scores, lesion sizes (mm) were entered as independent variables into a multivariate logistic regression model. This model yielded an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve score of 0.67. Once the propensity scores were estimated, we matched patients in the two groups by setting calipers, using the stringency scores in the JMP software program, at a width equal to a distance of 0.2 from the standard deviation of the logit of the propensity score, without replacement. The effect of matching was evaluated in terms of the absolute standardized difference.

Results

Comparisons between MIAB and EUS-FNAB

A total of 177 SELs from 177 consecutive patients (male, n = 87; female, n = 90) were included in this study. The characteristics of the patients and lesions in both groups are summarized in Table 1. Seventy-one patients underwent MIAB, and 106 underwent EUS-FNAB. There were no significant differences between the groups in sex, age, lesion size, lesion location, or histological type. No procedure-related adverse events, including late-onset bleeding after discharge from hospital, major bleeding, or gastric perforation, occurred in either group. The success rate of tissue sampling was higher with MIAB than with EUS-FNAB (95.6% vs. 86.8%, respectively; P = 0.047). Accordingly, the diagnostic yield of MIAB was significantly higher than that of EUS-FNAB (94.3% vs. 79.2%, respectively; P = 0.013). However, MIAB took significantly longer to perform than EUS-FNAB (31.5 min vs. 21 min, respectively; P < 0.0001). Among the SELs successfully diagnosed by either MIAB or EUS-FNAB, 102 were diagnosed as GISTs, 69 of which were surgically resected in one of the five participating hospitals; all were confirmed to be GISTs.

Table 1.

Patient and lesion characteristics

| MIAB group | EUS-FNAB group | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 71 | 106 | |

| Gender; male/female | 31/40 | 56/50 | n.s. (P = 0.23) |

| Age; median & range | 62 (27–84) | 63 (27–87) | n.s. (P = 0.95) |

| Lesion size (mm); median & range | 19.6 (8.8–48) | 20.0 (9–63) | n.s. (P= 0.096) |

| Number of lesions in each gastric location | n.s. (P= 0.61) | ||

| Upper stomach | 40 | 66 | |

| Middle stomach | 18 | 26 | |

| Lower stomach | 13 | 14 | |

| Procedural time (min); median & range | 31.5 (9–160) | 21.0 (8–55) | P < 0.0001 |

| Success rate of tissue sampling | 95.6% (68/71) | 86.8% (92/106) | P = 0.047 |

| Diagnostic yield | 94.3% (67/71) | 79.2% (84/106) | P = 0.013 |

| Complication rate | 0% (0/71) | 0% (0/106) | n.s (P = 1.0) |

| Number of lesions of each histology type | n.s. (P = 0.053) | ||

| GIST | 53.5% (38/71) | 60.4% (64/106) | |

| Leiomyoma | 25.3% (18/71) | 11.3% (12/106) | |

| Schwannoma | 2.8% (2/71) | 3.8% (4/106) | |

| Aberrant pancreas | 8.5% (6/71) | 2.8% (3/106) | |

| Glomus tumor | 1.4% (1/71) | – | |

| Lipoma | 1.4% (1/71) | – | |

| Inflammatory change | 1.4% (1/71) | – | |

| Renal cell carcinoma | – | 0.9% (1/106) | |

| Matching rate of pre- and post-operative diagnoses | 100% (35/35) | 100% (34/34) | n.s. (P = 1.0) |

The effects of SEL size and location on diagnostic yields of EUS-FNAB and MIAB

As shown in Table 2, the diagnostic yield with EUS-FNAB for SELs < 20-mm diameter was significantly lower than with SELs ≥20-mm diameter (88.0% vs 71.4%, respectively; P = 0.048). In contrast, the diagnostic yield with MIAB was not affected by lesion size (92.3% vs 93.3%, < 20-mm vs ≥ 20-mm diameter, respectively; P = 0.51). The diagnostic yields for samples from the upper/middle/lower parts of the stomach were 92.5%/88.9%/100% with MIAB and 84.5%/76.9%/57.1% with EUS-FNAB. SEL location did not affect the diagnostic yield with either procedure (P = 0.48 with MIAB and P = 0.067 with EUS-FNAB).

Table 2.

Relationships between lesion size and location, and diagnostic yields with MIAB and EUS-FNAB

| MIAB group | P value | EUS-FNAB group | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lesion sizes and diagnostic yield | ≥ 20 mm: 92.3% | n.s. (P = 0.51) | ≥ 20 mm: 88.0% | P = 0.048 |

| < 20 mm: 93.3% | < 20 mm: 71.4% | |||

| Lesion locations and diagnostic yield | Upper: 92.5% | n.s. (P = 0.48) | Upper: 84.5% | n.s. (P = 0.067) |

| Middle: 88.9% | Middle: 76.9% | |||

| Lower: 100% | Lower: 57.1% |

Comparison of MIAB and EUS-FNAB before and after propensity-score matching

Because the initial analyses suggested the superiority of MIAB over EUS-FNAB, especially for diagnosing SELs < 20-mm diameter, the SELs were divided into two groups (≥ 20-mm and < 20-mm diameter) and MIAB and EUS-FNAB compared (Fig. 1, Tables 3 and 4). For this comparison, lesion sizes were matched between the MIAB and EUS-FNA groups using propensity-score matching analysis. As shown in Tables 3 and 4, after matching propensity scores on the basis of lesion size, there was no difference between the two groups in patient characteristics or sizes and locations of lesions. The procedural times for MIAB and EUS-FNAB for SELs ≥20-mm diameter were 32 min and 20.5 min, respectively, whereas procedural times for MIAB and EUS-FNAB for SELs < 20-mm diameter were 31 min and 20 min, respectively. MIAB took significantly longer to perform (on average, 12–14 min longer) than EUS-FNAB, regardless of lesion size. For SELs ≥20-mm diameter, the success rate of tissue sampling and diagnostic yields did not differ significantly between the two procedures (P = 0.55) (Table 3). However, for SELs < 20-mm diameter, MIAB yielded a significantly higher successful diagnosis rate than did EUS-FNAB (93.5% vs. 61.2%, respectively; P = 0.011) (Table 4). The results of the analysis after matching the propensity scores based on lesion sizes and locations are shown in Additional file 1: Table S1. Again, the procedural time was significantly longer for MIAB than EUS-FNAB for all sizes of SELs. Both the success rate of tissue sampling and the diagnostic yield were higher with MIAB than with EUS-FNAB for SELs < 20 mm.

Table 3.

Comparison of MIAB and EUS-FNAB in diagnosing SELs ≥20-mm diameter (using the matching factor of lesion size)

| Before matching | After matching | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIAB group | EUS-FNAB group | P value | MIAB group | EUS-FNAB group | P value | |

| Number of patients | 26 | 50 | n.s. (P = 0.051) | 25 | 25 | n.s. (P = 1.0) |

| Gender; male/female | 10/16 | 19/31 | n.s. (P = 0.051) | 10/15 | 11/14 | n.s. (P = 0.77) |

| Age; median & range | 62.5 (24–79) | 63.5 (28–78) | n.s. (P = 0.88) | 62 (24–79) | 68 (36–77) | n.s. (P = 0.27) |

| Lesion size (mm); median & range | 26.2 (20–48) | 28 (20–63) | P = 0.040 | 25 (20–36) | 24 (20–36) | n.s. (P = 0.95) |

| Number of lesions in each gastric location | n.s. (P = 0.98) | n.s. (P = 0.93) | ||||

| Upper stomach | 16 | 32 | 15 | 16 | ||

| Middle stomach | 5 | 9 | 5 | 5 | ||

| Lower stomach | 5 | 9 | 5 | 4 | ||

| Procedural time (min); median & range | 32 (9–70) | 22.5 (8–55) | P = 0.043 | 32 (9–70) | 20.5 (8–41) | P = 0.018 |

| Success rate of tissue sampling | 96.1% (25/26) | 90.0% (45/50) | P = 0.062 | 96.0% (24/25) | 96.0% (24/25) | n.s. (P = 1.0) |

| Diagnostic yield | 92.3% (24/26) | 88.0% (44/50) | n.s. (P = 0.56) | 96.0% (24/25) | 96.0% (24/25) | n.s. (P = 1.0) |

| Complication rate | 0% (0/26) | 0% (0/50) | n.s. (P = 1.0) | 0% (0/25) | 0% (0/25) | n.s. (P = 1.0) |

| Number and frequency of lesions of each histology type | n.s. (P = 0.12) | n.s. (P = 0.091) | ||||

| GIST | 65.3% (17/26) | 64.0% (32/50) | 64% (16/25) | 88% (22/25) | ||

| Leiomyoma | 23.1% (6/26) | 16.0% (8/50) | 24% (6/25) | 4% (1/25) | ||

| Schwannoma | – | 6.0% (3/50) | – | 4% (1/25) | ||

| Aberrant pancreas | 8.0% (2/26) | – | 8% (2/25) | – | ||

| Renal cell carcinoma | 2.0% (1/50) | – | – | |||

Table 4.

Comparison of MIAB and EUS-FNAB in diagnosing SELs < 20-mm diameter (using the matching factor of lesion size)

| Before matching | After matching | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIAB group | EUS-FNAB group | P value | MIAB group | EUS-FNAB group | P value | |

| Number of patients | 45 | 56 | n.s. (P = 0.84) | 31 | 31 | n.s. (P = 1.0) |

| Gender; male/female | 21/24 | 25/31 | n.s. (P = 0.84) | 14/17 | 13/18 | n.s. (P = 0.80) |

| Age; median & range | 62.0 (27–84) | 62.0 (27–87) | n.s. (P = 0.98)> | 62.0 (27–82) | 64.0 (27–83) | n.s. (P = 0.77) |

| Lesion size (mm); median & range | 15.0 (8.8–19.8) | 16.0 (9.0–19.8) | n.s. (P = 0.84) | 17 (8.8–19.8) | 15 (9–19.8) | n.s. (P = 0.99) |

| Number of lesions in each gastric location | n.s. (P = 0.41) | n.s. (P = 0.92) | ||||

| Upper stomach | 24 | 34 | 18 | 18 | ||

| Middle stomach | 13 | 17 | 8 | 9 | ||

| Lower stomach | 8 | 5 | 5 | 4 | ||

| Procedural time (min); median & range | 31 (10–160) | 20 (9–49) | P < 0.001 | 31 (10–160) | 20 (10–49) | P = 0.0093 |

| Success rate of tissue sampling | 97.8% (44/45) | 85.7% (48/56) | P = 0.34 | 93.5% (29/31) | 61.3% (19/31) | P = 0.011 |

| Diagnostic yield | 93.3% (42/45) | 71.4% (40/56)> | P = 0.005 | 93.5% (29/31) | 61.3% (19/31) | P = 0.011 |

| Complication rate | 0% (0/45) | 0% (0/56) | n.s. (P = 1.0) | 0% (0/31) | 0% (0/31) | n.s. (P = 1.0) |

| Number and frequency of lesions of each histology type | n.s. (P = 0.066) | n.s. (P = 0.14) | ||||

| GIST | 46.7% (21/45) | 57.1% (32/56) | 48.4% (15/31) | 42.0% (13/31) | ||

| Leiomyoma | 26.7% (12/45) | 8.9% (5/56) | 25.8% (8/31) | 12.9% (4/31) | ||

| Schwannoma | 4.4% (2/45) | 1.7% (1/56) | 6.5% (2/31) | – | ||

| Aberrant pancreas | 8.9% (4/45) | 3.4% (2/56) | 6.5% (2/31) | 6.5% (2/31) | ||

| Glomus tumor | 2.2% (1/45) | – | – | – | ||

| Lipoma | 2.2% (1/45) | – | 3.2% (1/31) | – | ||

| Inflammatory change | 2.2% (1/45) | – | 3.2% (1/31) | – | ||

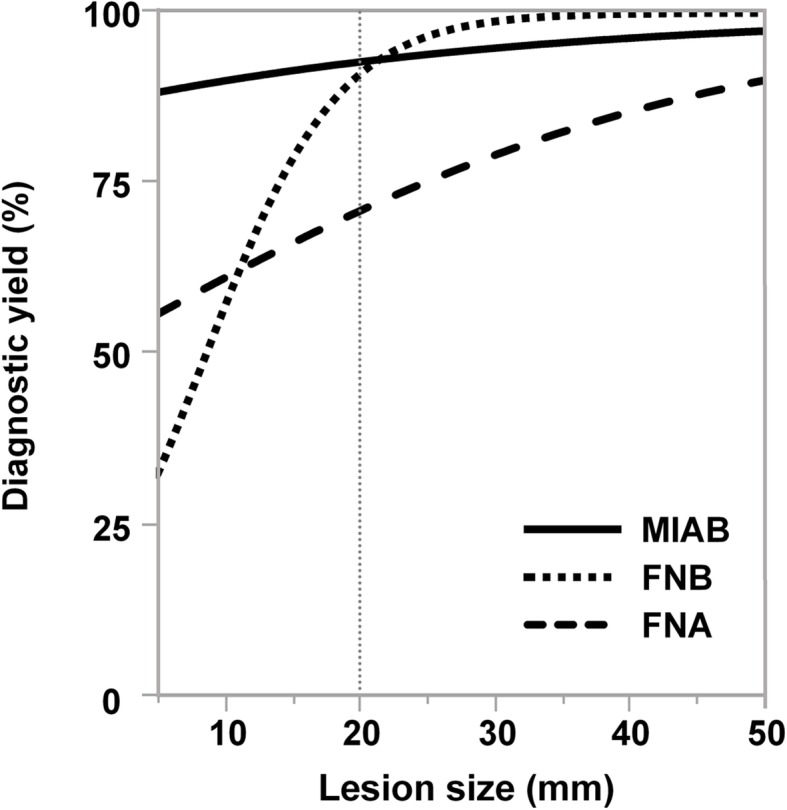

Comparison between EUS-FNA, EUS-FNB, and MIAB

Because previous reports have suggested that the more recently developed FNB needles are superior to FNA needles for collecting samples, especially for pancreatic lesions [12–14], the diagnostic yields of the two types of needles were compared with yields for MIAB. FNA needles were used for 69 and FNB needles for 37 of the 106 patients who underwent EUS-FNAB. For SELs ≥20-mm diameter, EUS-FNA and EUS-FNB were performed in 33 and 17 patients, respectively, whereas for SELs < 20-mm diameter, EUS-FNA and EUS-FNB were performed in 36 and 20 patients, respectively.

For SELs ≥20-mm diameter, the diagnostic yield of EUS-FNB (100%) was significantly higher than that of EUS-FNA (80.7%) (P = 0.041), but comparable to that of MIAB (96%) (P = 0.38). However, for SELs < 20-mm diameter, the diagnostic yields of EUS-FNA and EUS-FNB did not differ significantly (68.7 and 77.8%, respectively) (P = 0.065). For this size of SELs, MIAB outperformed both EUS-FNA and EUS-FNB (Tables 5, 6, Fig. 2).

Table 5.

Patient and lesion characteristics, who underwent EUS-FNA and EUS-FNB

| EUS-FNA group | EUS-FNB group | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 69 | 37 | |

| Gender; male/female | 33/36 | 23/14 | n.s. (P = 0.16) |

| Age; median & range | 62 (27–87) | 65 (36–78) | n.s. (P = 0.42) |

| Lesion size (mm); median & range | 20.0 (9–58) | 21.0 (10–63) | n.s. (P = 0.94) |

| Number of lesions in each gastric location | n.s. (P = 0.22) | ||

| Upper stomach | 41 | 25 | |

| Middle stomach | 16 | 10 | |

| Lower stomach | 12 | 2 | |

| Procedural time (min); median & range | 22 (9–55) | 20 (8–49) | n.s. (P = 0.76) |

| Success rate of tissue sampling | 84.1% (58/69) | 91.9% (34/37) | n.s. (P = 0.26) |

| Diagnostic yield | 73.9% (51/69) | 89.2% (33/37) | n.s. (P = 0.065) |

| Complication rate | 0% (0/69) | 0% (0/37) | n.s. (P = 1.0) |

Table 6.

Comparison of EUS-FNA and EUS-FNB in diagnosing SELs

| SELs < 20 mm | SELs ≥ 20 mm | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EUS-FNA group | EUS-FNB group | P value | EUS-FNA group | EUS-FNB group | P value | |

| Number of patients | 38 | 18 | 31 | 19 | ||

| Gender; male/female | 16/22 | 9/9 | n.s. (P = 0.58) | 17/14 | 14/5 | n.s. (P = 0.18) |

| Age; median & range | 62.5 (27–87) | 60.5 (38–77) | n.s. (P = 0.95) | 61 (28–77) | 66 (36–78) | n.s. (P = 0.20) |

| Lesion size (mm); median & range | 15 (9–19.8) | 16 (10–19.8) | n.s. (P = 0.35) | 30 (20–58) | 26 (20–63) | n.s. (P = 0.86) |

| Number of lesions in each gastric location | n.s. (P = 0.27) | n.s. (P = 0.94) | ||||

| Upper stomach | 22 | 12 | 19 | 13 | ||

| Middle stomach | 11 | 6 | 5 | 4 | ||

| Lower stomach | 5 | 0 | 7 | 2 | ||

| Procedural time (min); median & range | 20 (9–37) | 23 (11–49) | n.s. (P = 0.18) | 25 (9–55) | 19 (8–41) | n.s. (P = 0.41) |

| Success rate oftissue sampling | 79.0% (30/38) | 83.3% (15/18) | n.s. (P = 0.70) | 90.3% (28/31) | 100% (19/19) | n.s. (P = 0.16) |

| Diagnostic yield | 68.4% (26/38) | 77.8% (14/18) | n.s. (P = 0.47) | 80.1% (25/31) | 100% (19/19) | P = 0.041 |

| Complication rate | 0% (0/38) | 0% (0/18) | n.s. (P = 1.0) | 0% (0/31) | 0% (0/19) | n.s. (P = 1.0) |

Fig. 2.

Relationships between the lesion sizes and diagnostic yields. The regression curves for MIAB, EUS-FNA, EUS-FNB were generated from the data shown in Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6

Discussion

To diagnose GISTs, immunohistochemical staining for several antigens, such as c-Kit, DOG1, and S-100, is necessary [4, 15–18]. Obtaining samples large enough to perform several immunohistochemical evaluations is sometimes very difficult when performing EUS-FNAB, especially when the lesion is small [19]. This leads to failure in making a diagnosis despite time-consuming procedures and on-site evaluations by pathologists. The reported diagnostic yield of EUS-FNAB for small gastric SELs is 62–82% [19, 20].

In the current study, we showed the superiority of MIAB over EUS-FNAB for diagnosing gastric SELs with intraluminal growth < 20-mm diameter. Our findings are partially consistent with a previous study that reported comparable diagnostic yields with MIAB and EUS-FNAB for gastric SELs [7]. However, in that study the lesions were not classified into small and large groups; MIAB is especially useful for obtaining samples from small SELs. Although metastasis or invasion of GISTs < 20 mm diameter is considered very rare [21, 22], many guidelines recommend surgical resection of GISTs, regardless of the lesion size. We have encountered a patient with metastasis from a GIST of approximately 15 mm diameter [23]. Improving biopsy skills for such small SELs is necessary. MIAB does not require EUS during biopsy, nor does it require on-site evaluation by cytologists or pathologists. With MIAB, it is immediately evident whether samples sufficient for histological evaluation have been obtained. Therefore, MIAB could be preferable considering the possibility of diagnostic failure following FNAB and situations where EUS systems are unavailable. Very similar open biopsy techniques, such as single-incision needle-knife biopsy (SINK) and unroofing biopsy have also been reported [24–26]. These procedures may have advantages similar to those of MIAB.

The designs of aspiration needles have been modified to enable collection of larger biopsy samples, including development of the so-called fine needle biopsy (FNB) needles. Although FNB needles are reportedly superior to conventional FNA needles for the diagnosis of pancreatic lesions, their usefulness for diagnosis of gastric SELs is controversial [27–29]. Our findings suggest that the diagnostic yields with EUS-FNA, EUS-FNB, and MIAB are comparable for SELs ≥20-mm diameter. For SELs < 20-mm diameter, our results are consistent with those reported for pancreatic lesions, where FNB needles outperformed FNA needles. However, MIAB outperformed both FNA and FNB needles in terms of diagnostic yield.

The strategies for the treatment of SELs with diameters within the range of 20–50-mm slightly differ among guidelines. The Japanese guidelines recommend biopsy for such SELs, whereas the European and American guideline recommends either performing biopsy or directly resecting the lesion [4–6]. In our study, despite the fact that all patients who underwent biopsy were suspected of having tumorous lesions on the basis of EUS findings, a few lesions turned out to be non-tumorous, such as the aberrant pancreas and inflammatory reactions. Because a few SELs show atypical EUS findings, we think biopsy is the preferable approach than direct surgery for SELs within 20–50-mm diameter. The diagnostic yield with MIAB for SELs within this range were comparable to that with EUS-FNAB. However, considering the fact that MIAB takes longer to perform and is only effective for SELs with intraluminal growth, EUS-FNAB would remain the standard biopsy procedure for SELs with diameters within this range.

Our study also revealed that MIAB and EUS-FNAB are very safe techniques. No major or minor adverse events were reported in our hospitals. Although MIAB uses skills and devices developed for endoscopic submucosal dissection, the adverse event rate following MIAB was much lower than that reported for endoscopic submucosal dissection. The incidence of bleeding in patients undergoing endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric mucosal tumors is reportedly 2–15% [30–35] . The lower rate with MIAB is likely because this procedure requires only a partial incision into the normal mucosa covering the SEL, whereas with endoscopic submucosal dissection an entire tumor of epithelial origin (i.e., adenoma or adenocarcinoma) is resected. Such epithelial tumors are usually fed by thick vessels from the submucosal layer; thus, endoscopic submucosal dissection requires transecting those vessels, which could lead to major or late-onset bleeding. Our data suggest that MIAB is a safe and reliable approach; however, one concern about this procedure is that it exposes tumor cells of GISTs by disrupting the fibrous pseudocapsule within which those tumor cells are usually encapsulated. EUS-FNAB also requires piercing of the pseudocapsule; however, the area that is disrupted (a pinhole) is much smaller than that with MIAB. Thus, in MIAB, more cells could be released into the gastric lumen from the biopsied area. It is unlikely that such freed tumor cells would attach to and grow in other parts of the gastrointestinal tract; however, when the stomach is perforated during an unsatisfactory procedure and gastric contents are released into the abdominal cavity, the chances of tumor seeding may be increased. Although we have not encountered MIAB-associated perforation or tumor seeding, great care should be taken to avoid this. In particular, MIAB should be performed only on lesions that are visible by conventional endoscopy.

As to limitations, this study had a retrospective design. Thus, our findings require confirmation by a prospective randomized trial; however, our data provide reasonable support for open biopsy as an option for obtaining samples from gastric SELs.

Conclusions

In conclusion, although MIAB takes approximately 13 min longer to perform than EUS-FNAB, MIAB provides significantly better diagnostic yields for gastric SELs smaller than 20-mm diameter with intraluminal growth, regardless of their location. MIAB may be a good option for diagnosing small gastric SELs. In our study, the diagnostic yields with MIAB and EUS-FNAB were comparable for gastric SELs ≥20-mm diameter. Considering the shorter procedural time required, EUS-FNAB should remain the standard for diagnosing larger lesions.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Table S1. Comparison of MIAB and EUS-FNAB in diagnosing SELs < 20-mm diameter (using the matching factors of lesion size and location).

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- EGD

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy

- EMR

Endoscopic mucosal resection

- ESD

Endoscopic submucosal dissection

- EUS-FNAB

Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration/ biopsy

- FNB

Fine needle biopsy

- GIST

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor

- MIAB

Mucosal incision-assisted biopsy

- PPI

Proton pump inhibitor

- ROSE

Rapid on-site evaluation

- SEL

Subepithelial lesion

- SINK

Single-incision needle-knife biopsy

Authors’ contributions

YM designed the study, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. TC edited the manuscript. EI collected data and critically reviewed the manuscript. TO, SI, KH, HA, AA, YS, KK, HO, and YO contributed to collection of the data. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committees of the Kyushu University Hospital (Approval No. 29–465), Kyushu Medical Center (Approval No. 17C366), Kyushu Rosai Hospital (Approval No. 17–27), Harasanshin Hospital (Approval No. 2017–31), and Kitakyushu Municipal Medical Center (Approval No. 201801056). Written informed consent for biopsy procedures was obtained from all patients. This study was approved by the ethics committees of all five hospitals.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12876-020-1170-2.

References

- 1.Hedenbro JL, Ekelund M, Wetterberg P. Endoscopic diagnosis of submucosal gastric lesions. The results after routine endoscopy. Surg Endosc. 1991;5(1):20–23. doi: 10.1007/BF00591381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nishida T, Hirota S. Biological and clinical review of stromal tumors in the gastrointestinal tract. Histol Histopathol. 2000;15(4):1293–1301. doi: 10.14670/HH-15.1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crosby JA, Catton CN, Davis A, Couture J, O'Sullivan B, Kandel R, Swallow CJ. Malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the small intestine: a review of 50 cases from a prospective database. Ann Surg Oncol. 2001;8(1):50–59. doi: 10.1007/s10434-001-0050-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nishida T, Kawai N, Yamaguchi S, Nishida Y. Submucosal tumors: comprehensive guide for the diagnosis and therapy of gastrointestinal submucosal tumors. Dig Endosc. 2013;25(5):479–489. doi: 10.1111/den.12149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casali PG, Abecassis N, Aro HT, Bauer S, Biagini R, Bielack S, Bonvalot S, Boukovinas I, Bovee J, Brodowicz T, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: ESMO-EURACAN Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(Supplement_4):iv267. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Faulx AL, Kothari S, Acosta RD, Agrawal D, Bruining DH, Chandrasekhara V, Eloubeidi MA, Fanelli RD, Gurudu SR, Khashab MA, et al. The role of endoscopy in subepithelial lesions of the GI tract. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85(6):1117–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2017.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ikehara H, Li Z, Watari J, Taki M, Ogawa T, Yamasaki T, Kondo T, Toyoshima F, Kono T, Tozawa K, et al. Histological diagnosis of gastric submucosal tumors: a pilot study of endoscopic ultrasonography-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy vs mucosal cutting biopsy. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;7(14):1142–1149. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v7.i14.1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kobara H, Mori H, Fujihara S, Nishiyama N, Tani J, Morishita A, Oryu M, Tsutsui K, Masaki T. Endoscopically visualized features of gastric submucosal tumors on submucosal endoscopy. Endoscopy. 2014;46(Suppl 1):E660–E661. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1390840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee HL, Kwon OW, Lee KN, Jun DW, Eun CS, Lee OY, Jeon YC, Han DS, Yoon BC, Choi HS, et al. Endoscopic histologic diagnosis of gastric GI submucosal tumors via the endoscopic submucosal dissection technique. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74(3):693–695. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ihara E, Matsuzaka H, Honda K, Hata Y, Sumida Y, Akiho H, Misawa T, Toyoshima S, Chijiiwa Y, Nakamura K, et al. Mucosal-incision assisted biopsy for suspected gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;5(4):191–196. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v5.i4.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Osoegawa T, Minoda Y, Ihara E, Komori K, Aso A, Goto A, Itaba S, Ogino H, Nakamura K, Harada N, et al. Mucosal incision-assisted biopsy versus endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration with a rapid on-site evaluation for gastric subepithelial lesions: a randomized cross-over study. Dig Endosc. 2019;31(4):413–21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Bang JY, Hebert-Magee S, Trevino J, Ramesh J, Varadarajulu S. Randomized trial comparing the 22-gauge aspiration and 22-gauge biopsy needles for EUS-guided sampling of solid pancreatic mass lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76(2):321–327. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.03.1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Larghi A, Iglesias-Garcia J, Poley JW, Monges G, Petrone MC, Rindi G, Abdulkader I, Arcidiacono PG, Costamagna G, Biermann K, et al. Feasibility and yield of a novel 22-gauge histology EUS needle in patients with pancreatic masses: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Surg Endosc. 2013;27(10):3733–3738. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-2957-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Facciorusso A, Del Prete V, Buccino VR, Purohit P, Setia P, Muscatiello N. Diagnostic yield of Franseen and fork-tip biopsy needles for endoscopic ultrasound-guided tissue acquisition: a meta-analysis. Endosc Int Open. 2019;7(10):E1221–e1230. doi: 10.1055/a-0982-2997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.West RB, Corless CL, Chen X, Rubin BP, Subramanian S, Montgomery K, Zhu S, Ball CA, Nielsen TO, Patel R, et al. The novel marker, DOG1, is expressed ubiquitously in gastrointestinal stromal tumors irrespective of KIT or PDGFRA mutation status. Am J Pathol. 2004;165(1):107–113. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63279-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bucher P, Villiger P, Egger JF, Buhler LH, Morel P. Management of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: from diagnosis to treatment. Swiss Med Wkly. 2004;134(11–12):145–153. doi: 10.4414/smw.2004.10530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blay JY, Bonvalot S, Casali P, Choi H, Debiec-Richter M, Dei Tos AP, Emile JF, Gronchi A, Hogendoorn PC, Joensuu H, et al. Consensus meeting for the management of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Report of the GIST Consensus Conference of 20–21 March 2004, Under the auspices of ESMO. Ann Oncol. 2005;16(4):566–578. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Corless CL, Barnett CM, Heinrich MC. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: origin and molecular oncology. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(12):865–878. doi: 10.1038/nrc3143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akahoshi K, Oya M, Koga T, Koga H, Motomura Y, Kubokawa M, Gibo J, Nakamura K. Clinical usefulness of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration for gastric subepithelial lesions smaller than 2 cm. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2014;23(4):405–412. doi: 10.15403/jgld.2014.1121.234.eug. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Larghi A, Fuccio L, Chiarello G, Attili F, Vanella G, Paliani GB, Napoleone M, Rindi G, Larocca LM, Costamagna G, et al. Fine-needle tissue acquisition from subepithelial lesions using a forward-viewing linear echoendoscope. Endoscopy. 2014;46(1):39–45. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1344895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fletcher CD, Berman JJ, Corless C, Gorstein F, Lasota J, Longley BJ, Miettinen M, O'Leary TJ, Remotti H, Rubin BP, et al. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a consensus approach. Hum Pathol. 2002;33(5):459–465. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2002.123545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miettinen M, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: pathology and prognosis at different sites. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2006;23(2):70–83. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aso A, Ihara E, Kubo H, Osoegawa T, Oono T, Nakamura K, Ito T, Kakeji Y, Mikako O, Yamamoto H, et al. Gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumor smaller than 20 mm with liver metastasis. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2013;6(1):29–32. doi: 10.1007/s12328-012-0351-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de la Serna-Higuera C, Perez-Miranda M, Diez-Redondo P, Gil-Simon P, Herranz T, Perez-Martin E, Ochoa C, Caro-Paton A. EUS-guided single-incision needle-knife biopsy: description and results of a new method for tissue sampling of subepithelial GI tumors (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74(3):672–676. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shimamura Y, Hwang J, Cirocco M, May GR, Mosko J, Teshima CW. Efficacy of single-incision needle-knife biopsy for sampling subepithelial lesions. Endosc Int Open. 2017;5(1):E5–e10. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-122334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee CK, Chung IK, Lee SH, Lee SH, Lee TH, Park SH, Kim HS, Kim SJ, Cho HD. Endoscopic partial resection with the unroofing technique for reliable tissue diagnosis of upper GI subepithelial tumors originating from the muscularis propria on EUS (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71(1):188–194. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Inoue T, Okumura F, Sano H, Mizushima T, Tsukamoto H, Fujita Y, Ibusuki M, Kitano R, Kobayashi Y, Ishii N, et al. Impact of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle biopsy on the diagnosis of subepithelial tumors: a propensity score-matching analysis. Dig Endosc. 2019;31(2):156–163. doi: 10.1111/den.13269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Han JP, Lee TH, Hong SJ, Kim HK, Noh HM, Lee YN, Choi HJ. EUS-guided FNA and FNB after on-site cytological evaluation in gastric subepithelial tumors. J Dig Dis. 2016;17(9):582–587. doi: 10.1111/1751-2980.12381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang XC, Li QL, Yu YF, Yao LQ, Xu MD, Zhang YQ, Zhong YS, Chen WF, Zhou PH. Diagnostic efficacy of endoscopic ultrasound-guided needle sampling for upper gastrointestinal subepithelial lesions: a meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 2016;30(6):2431–2441. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4494-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park YM, Cho E, Kang HY, Kim JM. The effectiveness and safety of endoscopic submucosal dissection compared with endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Surg Endosc. 2011;25(8):2666–2677. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-1627-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chung IK, Lee JH, Lee SH, Kim SJ, Cho JY, Cho WY, Hwangbo Y, Keum BR, Park JJ, Chun HJ, et al. Therapeutic outcomes in 1000 cases of endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric neoplasms: Korean ESD study group multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69(7):1228–1235. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koh R, Hirasawa K, Yahara S, Oka H, Sugimori K, Morimoto M, Numata K, Kokawa A, Sasaki T, Nozawa A, et al. Antithrombotic drugs are risk factors for delayed postoperative bleeding after endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric neoplasms. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78(3):476–483. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lim JH, Kim SG, Kim JW, Choi YJ, Kwon J, Kim JY, Lee YB, Choi J, Im JP, Kim JS, et al. Do antiplatelets increase the risk of bleeding after endoscopic submucosal dissection of gastric neoplasms? Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75(4):719–727. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goto O, Fujishiro M, Oda I, Kakushima N, Yamamoto Y, Tsuji Y, Ohata K, Fujiwara T, Fujiwara J, Ishii N, et al. A multicenter survey of the management after gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection related to postoperative bleeding. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57(2):435–439. doi: 10.1007/s10620-011-1886-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Isomoto H, Shikuwa S, Yamaguchi N, Fukuda E, Ikeda K, Nishiyama H, Ohnita K, Mizuta Y, Shiozawa J, Kohno S. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer: a large-scale feasibility study. Gut. 2009;58(3):331–336. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.165381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Comparison of MIAB and EUS-FNAB in diagnosing SELs < 20-mm diameter (using the matching factors of lesion size and location).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.