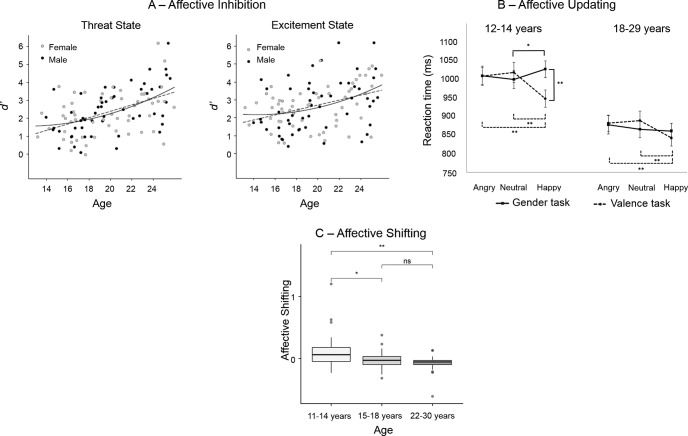

Figure 1.

Development of the three facets of affective control. The three panels show different facets of affective control (task performance/reaction time [RT] is always contrasted with performance in neutral contexts). (A) Age-related improvements from adolescence to adulthood in affective inhibition measured as d′ (ratio of hits to misses) on a go/no-go task performed in experimentally induced affective states of threat (anticipation of noxious noise) and excitement (anticipation of monetary reward) compared to a neutral state. The left panel shows a linear improvement in inhibition performance with age in the neutral state (i.e., cool cognitive control). The middle and right panels show a quadratic association between task performance and age when experiencing threat and excitement (i.e., affective control), respectively. From “When Is an Adolescent an Adult? Assessing Cognitive Control in Emotional and Nonemotional Contexts,” by A. O. Cohen, K. Breiner, L. Steinberg, R. J. Bonnie, E. S. Scott, K. A. Taylor-Thompson, . . . B. J. Casey, 2016, Psychological Science, 27, p. 557. Copyright 2016 by SAGE. Reprinted with permission. (B) An updating task with two conditions, both of which require affective control. Whereas in the valence task affective control is required to update affective material, in the gender task individuals are required to inhibit affective task-irrelevant features in order to attend to their nonaffective features (gender task). The gender task shows age-specific slowing in affective updating of task-irrelevant happy cues on an n-back task. This is demonstrated in the left panel, which shows adolescents’ slowed RTs to happy faces compared to neutral and angry faces when they are task-irrelevant (gender task/solid line). In the right panel, adults’ RTs to affective stimuli are unaffected by the valence of the stimuli in the gender task. In contrast, there are no age-related effects on affective updating when the memoranda are affective. That is, updating is fastest for positive cues in the valence task (stippled line) for both adults and adolescents. From “The Power of a Smile: Stronger Working Memory Effects for Happy Faces in Adolescents Compared to Adults,” by S. Cromheeke and S. C. Mueller, 2016, Cognition and Emotion, 30, p. 294. Copyright 2016 by Taylor & Francis. Reprinted with permission. (C) Better affective shifting (measured as the proportional difference in errors for the affective relative to neutral condition) performance in early adolescence than later in development is shown. Unlike inhibition and updating, these results suggest greater affective shifting capacity in early adolescence compared to later in development when performance is no longer affected by the valence of the stimuli. From “Age-Related Differences in Affective Control and Its Association With Mental Health Difficulties,” by S. Schweizer, J. Parker, J. T. Leung, C. Griffin, and S.-J. Blakemore, 2019, Development and Psychopathology (in the public domain).