This brief communication presents case reports for two patients with metastatic melanoma treated with empiric BRAF and MEK inhibitors.

Keywords: Global oncology, Capacity building, Medical education

Abstract

Background.

Sub‐Saharan Africa is simultaneously facing a rising incidence of cancer and a dearth of medical professionals because of insufficient training numbers and emigration, creating a growing shortage of cancer care. To combat this, Massachusetts General Hospital and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center partnered with institutions in South Africa, Tanzania, and Rwanda to develop a fellowship exchange program to supplement the training of African oncologists practicing in their home countries.

Methods.

In its initial year, 2018, the Program for Enhanced Training in Cancer (POETIC) hosted a pilot cohort of seven fellows for 3‐week observerships in their areas of interest. Researchers distributed questionnaires for program evaluation to participants prior to arrival and upon departure; additionally, three participated in semistructured interviews.

Results.

Five themes emerged from the qualitative data: expectations of POETIC, differences between oncology in the U.S. and in sub‐Saharan Africa, positive elements of the program, areas for improvement, and potential impact. Fellows identified several elements of Western health care that will inform their practice: patient‐centered care; clinical trials; and collaboration among medical, radiation, and surgical oncologists. From the quantitative data, feedback was primarily around logistical areas for improvement.

Conclusion.

POETIC was found to be feasible and valuable. The results from the pilot year justify the program's continuation in hopes of strengthening global health partnerships to support oncology training in Africa. One weakness is the small number of fellows, which will limit the impact of the study and the relevance of its conclusions. Future research will report on the expansion of the program and follow‐up with former participants.

Implications for Practice.

This work presents a novel model for fellowship exchange between lower‐ and higher‐resourced areas. The program is a short‐term observership with tumor boards and didactic teaching sessions incorporated. By attracting oncologists who aim to practice in their home countries, it facilitates international collaboration without contributing to the preexisting lack of medical professionals in low‐ and middle‐income countries.

Introduction

Cancer presents an ever‐evolving challenge in global medicine, one that manifests differently from region to region [1]. Its rising incidence demands a dedication to developing the oncology workforce, especially in underresourced areas. Accurate statistics on cancer in sub‐Saharan Africa (SSA) are difficult to ascertain, as the disease may be underdiagnosed and/or underreported. Nevertheless, the numbers available identify a growing incidence, later stage diagnosis, and a significantly higher mortality burden than in the developed countries [2], [3].

Cancer is predicted to become a rapidly growing and increasingly serious medical challenge in SSA. Using the human development index as an indicator of socioeconomic development, one model forecasts that the number of new cancer cases worldwide will rise from 12.7 million in 2008 to 22.2 million in 2030 [1], 61% of which will be in low‐ and middle‐income countries [4]. Countries with a low human development index, such as those in sub‐Saharan Africa, are also predicted to assume the majority of the mortality burden [1]. Another projection to 2030 predicts that the incidence will double from the 2008 numbers based solely on demographic changes, even before consideration of other development‐related factors [5].

This increase in incidence of cancer is predicted to create a substantial gap in the resources, both human and institutional, required to provide medical care for these subjects. There exists at present a dearth of trained oncologists (surgical, medical, and radiation) in virtually every country, as well as deficiencies in radiation therapy facilities. Many countries, such as Mozambique, with 30 million people, and areas of the Congo, a country of 80,000,000 people, lack any available radiation therapy, whereas such facilities are now just being installed in Uganda and Rwanda [6]. The few training programs in South Africa, Tanzania, Ghana, and Nigeria are inadequate to provide skilled specialists for the subcontinent. Additionally, emigration of skilled professionals seeking an improved quality of life, higher salary, and political stability has further exacerbated this problem and has created an African workforce unable to meet the health care demands of the population [7].

Currently, despite having around 16% of the world's population, only 3% of health care workers reside in sub‐Saharan Africa [2]. Among these numbers, well‐trained oncologists are a rarity. A comprehensive survey of the global oncology workforce found that of the 32 African countries examined, 25 (78%) had more than 1,000 incident cases of cancer for every practicing clinical oncologist. Of these 25, 7 countries (22%) had no oncologist [8]. In response to these trends and the need to address the growing burden of disease with attention to supporting and growing a well‐trained workforce, oncologists at the Massachusetts General Hospital and the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (MGH/BIDMC) initiated the Program for Enhanced Training in Cancer (POETIC) in early 2018 in partnership with the Clinical Oncology Training Programs of the University of Cape Town in South Africa and Ocean Road Cancer Center in Tanzania. Its aim is to assist capacity‐building efforts in these countries by hosting their junior teaching faculty, as well as the most promising trainee oncologists from throughout SSA, for targeted experience in their areas of special interest as a supplement to their regular curriculum, emphasizing a multidisciplinary approach to cancer management.

Materials and Methods

Scholars were selected after an extensive application and interview process with their home institutions and then subsequently approved by the Boston‐based team. Applications included a letter of interest with particularly attention being paid to demonstrated interest, intent to stay in Africa, and ability to impact current oncology systems in their countries of origin. Eligible scholars were nearing the end of their training or early in their professional careers. Over the course of the year, seven scholarship recipients participated in a 3‐ to 6‐week observership. Schedules were tailored to fit individual interests in oncologic areas of interest to as great a degree as possible. During their time in Boston, fellows shadowed medical, radiation, and surgical oncologists as they evaluated and treated patients in multispecialty disease centers at the two participating hospitals; additionally, they participated in tumor board discussions and smaller didactic teaching sessions. They were also provided opportunities for establishing mentorship.

To characterize the experience, we utilized both quantitative and qualitative data gathered from the seven members of the 2018 POETIC cohort to evaluate the first years’ experience in the program. The team developed two questionnaires on Qualtrics: one to be administered to each fellow prior to arrival and another upon departure. These were designed to assess expectations of the program and success in meeting these objectives with a quantitative survey that also included a free response section for elaboration following each rating prompt.

To supplement this information, the team conducted semistructured interviews based on a guide developed to capture key elements of the fellows’ experience, including most valuable elements of the program, areas for improvement, and applications to their practice in their home countries in Africa. A coding scheme was developed using a combination of preset and emergent nodes. This qualitative information from the survey was coded along with the interview using NVivo 12 Pro software.

Results

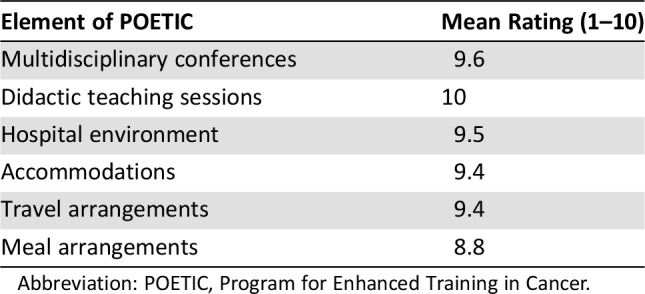

The 2018 cohort comprised six clinical oncologists as well as one surgical oncologist. Of the 2018 cohort, the quantitative data from the postprogram evaluation includes responses from the six clinical oncologists (Table 1). Table 1 demonstrates, with regard to each of survey items regarding experiences related to conference, teaching, hospital environment, accommodations, travel and meals, that the program was well received. Three participants including the surgical observer, a new faculty member with an interest in breast cancer, participated in the in‐depth interviews.

Table 1. Quantitative postprogram evaluations.

Abbreviation: POETIC, Program for Enhanced Training in Cancer.

Five thematic areas of interest (Table 2) were extracted from these quantitative and qualitative data: fellows’ expectations and hopes for the program, differences between practicing oncology in the U.S. and SSA, benefits garnered from POETIC, areas for program improvement, and hopes for future practice. Subthemes to each of these were identified and will be further developed.

Table 2. Highlighted themes from qualitative and quantitaive assessements.

Abbreviations: MGH/BIDMC, Massachusetts General Hospital and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center; POETIC, Program for Enhanced Training in Cancer.

Expectations and Hopes

The first theme related to the expectations that fellows had of the observership. Respondents hoped to understand the standard of care in a higher‐resourced area to guide capacity‐building efforts in their home countries. Additionally, they wanted to gain a deeper understanding of emerging therapies, and advanced radiotherapy techniques. One person likened it to assembling a “wish list for the future”; in other words, she used her time observing to develop a vision for the treatment modalities she hoped to gain access to in coming years in her home country. They additionally expressed a desire to observe multidisciplinary discussions. Prior to arrival, four of the six individuals who completed the preprogram questionnaire mentioned that they wanted to witness the interface of surgical, medical, and radiation oncology at tumor board panels. One person stated that their practice lacks this type of interaction because of lack of personnel, but that it would be helpful in the future to have multiple perspectives contributing to challenging cases. The final hope for the POETIC program was to forge relationships among Africa‐ and Boston‐based practitioners. Two people indicated that this would be especially helpful in a research context; additionally, they hoped to connect with faculty members at the participating institutions who could serve as mentors as they expanded their practice and academic activity.

Differences Between Practicing Oncology in the U.S. and SSA

The second major theme addresses differences between practicing oncology in the U.S. and in countries of origin in SSA. One commonly mentioned issue was the lack of trained oncologists. One fellow attributed this to a perceived general disinterest in the specialty. He went on to clarify that in the context of a high infectious disease burden, doctors are less inclined to want to tackle a disease like cancer that lacks an “evident … cure.” One major consequence of the lack of oncologists is that the few who practice do not have the luxury of subspecializing in a primary site. One respondent is one of three clinical oncologists for the Rwandan population of approximately 12 million, and he remarked on the tremendous workload he faces daily. Two people commented that even if there were designated medical, radiation, and surgical oncologists, it would be difficult to gather them at once for a multidisciplinary discussion because of their full schedules. Several fellows noted that their home countries do not have the necessary drugs and equipment; some referred to insufficient quantity and others to insufficient quality (i.e., treatments not on par with the Western standard of care). In addition to the treatments themselves, two individuals from different countries noted that their practice still occurs in a general hospital setting. The sentiment is that the first step to improving cancer care is establishing a facility in which all elements of oncology health care delivery (e.g., pathology, imaging, etc.) can be consolidated and streamlined.

Each of the three individuals who participated in the in‐depth interviewing identified a different cultural element that contributes to attitudes toward oncology in their country. One person said that “it's a general belief that cancer doesn't heal back home.” He views this as a barrier to cancer care, and along with another of the doctors pointed out that awareness is critical in promoting early detection and action. The third respondent reported that his patients tend to defer to his judgment without question because of their perception of him as an authority figure. In accordance with findings in the literature [3], one individual pointed out that his patients tend to present with later stage cancers. Another person pointed out that the MGH/BIDMC patients tend to have a greater amount of information at the outset, a finding in keeping with the observation that patients in SSA have less access to informational resources about their disease.

Only respondents from Rwanda and Tanzania spoke to this theme. These countries have lower human development indices compared with South Africa, for example. Therefore, this result cannot necessarily be generalized to the remainder of the region, some of which is higher resourced [9].

Benefits Garnered from POETIC

The third theme was the benefits that respondents garnered from their time in Boston, many of which overlapped with their hopes and expectations. Most were pleased with the exposure they received to the therapies being utilized and tested in Boston. Some of it related to the difference in patient populations; specifically, one fellow expressed an interest in seeing how nonmetastatic cancer is treated, because few such patients present at his clinic. A few other topics of interest were targeted agents, the medical record system, and pharmacology. The general sentiment was summed up well by one person: “You can … progress much quicker if you jump a few steps and arrive where people are today.”

The face‐to‐face time with Boston‐based clinicians gave fellows a sense of optimism about the potential for international collaboration. They were pleased about the connections forged and the opportunities for both parties to share elements of their practice. Additionally, four of the seven praised the multidisciplinary clinic as a setting in which to witness the various approaches that medical, surgical, and radiation oncologists take with a given patient. Beyond this, the interface between the three in one room gave a better understanding of how Western oncology divides responsibility and promotes collaboration.

Areas for Program Improvement

The fourth theme related to areas of improvement for POETIC. Most these were logistical, relating to improved coordination prior to arrival and smoother transitions between meetings. The program was generally well received, and nothing that impacted its scalability or expansion was mentioned.

Hopes for Future Practice

The final theme included fellows’ hopes for their future practice in Africa. Nearly every individual expressed a desire to integrate multidisciplinary clinics into their day‐to‐day operations in Africa. One person who filled out the postprogram questionnaire a few weeks after returning home had even already begun to do so. The general sentiment seemed to be that this approach to cancer treatment was one of the most important takeaway messages from POETIC and that this would be integral in expanding oncology services in their home countries.

Another piece of Western practice that the fellows found informative was the tendency of the clinicians to actively involve the patient in their own care. One person pointed out that it does not require any additional resources to do so; therefore, that it would require less effort to initiate it. Other specific elements of patient interaction that were noted as goals for future improvement were consistent communication and empowerment. This point was viewed as critical to scaling up African oncology and continuing to involve fellows’ institutions in global conversations.

Historically, African voices have been underrepresented in medical research [10], likely in part because the enormous patient volume per practitioner limits their capacity to focus on additional projects. One commonly expressed hope was that the relationships built with MGH/BIDMC providers would lead to future research collaborations and potential participation in clinical trials. The prospect of collaborating was the code that occurred the most frequently. Fellows hoped that their time in Boston would lead to mentor‐mentee relationships with people they can consult regarding challenging cases they face. With the shortage of doctors, their access to second opinions is somewhat limited, so the POETIC fellowship has in effect begun to create a remote human resource support system.

Finally, with respect to their outlook on cancer care in their home countries, fellows had overwhelmingly positive responses at the tail end of the fellowship. In addition to a renewed hope in the future of African cancer care, participants appeared to get affirmation that their training has prepared them well to introduce new treatment modalities into their institutions. One fellow reported that he left with “confidence in [his] training at the University of Cape Town as [he] realized that the language in oncology is similar.” Another individual reported that she “feel[s] inspired to improve [her] patients’ access to new drugs and treatments.” They left with an understanding that the resources are different, but the determination that these new connections will help shape their field.

Discussion

POETIC is one of several initiatives carving a path toward combating the lack of oncology‐related human resources in SSA. By selecting doctors who intend to practice in their home countries, POETIC deviates from the prototypical remote training model in which medical personnel spend long periods of time abroad and oftentimes remain there to work. To our knowledge, few fellowship exchange programs of this nature exist. Notable exceptions include the American Society of Clinical Oncology International Development and Education Award (IDEA) program [11], the Academic Model Providing Access to Healthcare (AMPATH) Research Program [12], Botswana Oncology Global Outreach (BOTSOGO) [13], [14], and several institutional twinning partnerships, including those between the Uganda Cancer Institute and Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center [15], Partners in Health and Butaro Cancer Center of Excellence [16], the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Malawi Ministry of Health [17], and the Duke Global Health Institute and Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre [18].

In addition to these training and research programs, there are ongoing efforts to correct other global resource disparities. One such type of work, notably performed by the American Society of Clinical Pathology, seeks to improve anatomic pathology quality and availability [19]. Additionally, several initiatives serve to increase delivery of anticancer drugs to low‐ and middle‐income countries. These include the expansion of the World Health Organization Model List of Essential Medicines in 2015 to include 16 new “cytotoxic and adjuvant medicines” [20] and the Access to Medicine Foundation's research efforts that guide such projects [21].

Fellows’ responses to the experience coalesced on few key elements of Western health care: patient‐centered interaction; multidisciplinary clinics representing medical, radiation, and surgical oncology; and the integration of trials into clinical decision‐making. Respondents tended to view these not as novel concepts per se but rather as best practices that ought to be implemented whenever the resources allow. However, these necessitate increased capacity in African oncology, whether through increased access to chemotherapy drugs, numbers of trained support staff to assist in clinical operations, or simply more doctors who can subspecialize and collaborate. Importantly, POETIC may inspire the framework for this capacity building; fellows can bring their understanding of operations in a fully resourced setting back to their home countries and thus be better able to set out a concrete plan for development. Additionally, this fellowship lays the foundation for international research collaboration. For example, the connections forged will be important for expanding clinical trials of pharmaceuticals that may be unavailable in lower‐resourced countries. Researchers conducting these trials must have a familiarity with the patient population and resources available. Collaborations of this sort would amplify the historically underrepresented voice of African scientists, in keeping with the equitable global health partnership model [10].

Conclusion

Limitations include the small number of participants and single study site. Nevertheless, this experience serves as an initial report upon which to build; future research will report on the expansion of the fellowship as well as its impact, as assessed by annual surveys administered to former fellows.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Eddie Reed Philanthropic Fund.

Author Contributions

Conception/design: Madeleine Fish, Jeannette Parkes, Nazima Dharsee, Scott Dryden‐Peterson, Jason Efstathiou, Lowell Schnipper, Bruce A. Chabner, Aparna R. Parikh

Collection and/or assembly of data: Madeleine Fish, Aparna R. Parikh

Data analysis and interpretation: Madeleine Fish, Aparna R. Parikh

Manuscript writing: Madeleine Fish, Aparna R. Parikh

Final approval of manuscript: Madeleine Fish, Jeannette Parkes, Nazima Dharsee, Scott Dryden‐Peterson, Jason Efstathiou, Lowell Schnipper, Bruce A. Chabner, Aparna R. Parikh

Disclosures

Jason Efstathiou: Blue Earth Diagnostics, Taris Biomedical (C/A), Janssen (SAB); Bruce A. Chabner: PharmaMar, EMD Serono, Cyteir (C/A, H), Biomarin, Seattle Genetics, PharmaMar, Loxo, Blueprint, Bluebird, Immunomedics (OI), Eli Lilly & Co., Genentech (ET); Aparna R. Parikh: Merck KG Africa Foundation, Leaf Pharmaceuticals (RF), UpToDate, Inc. (IP), Puretech, Foundation Medicine (SAB), Eisai, Research Array, Plexxicon, Guardant, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, MacroGenics, Genentech, Novartis, Oncomed, Tolero (C/A). The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

References

- 1.Bray F, Jemal A, Grey N et al. Global cancer transitions according to the Human Development Index (2008‐2030): A population‐based study. Lancet Oncol 2012;13:790–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:394–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jedy‐Agba E, McCormack V, Adebamowo PC et al. Stage at diagnosis of breast cancer in sub‐Saharan Africa: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2016;4:e923–e935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thun MJ, DeLancey JO, Center MM et al. The global burden of cancer: Priorities for prevention. Carcinogenesis 2010;31:100–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bakary SS, Wild CP. A million Africans a year dying from cancer by 2030: What can cancer research and control offer to the continent? Int J Cancer 2012;130:245–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grover S, Xu MJ, Yeager A et al. A systematic review of radiotherapy capacity in low‐ and middle‐income countries. Front Oncol 2015;4:380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Misau YA, Al‐Sadat N, Gerei AB. Brain‐drain and health care delivery in developing countries. J Public Health Africa 2010;1:e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mathew A. Global survey of clinical oncology workforce. J Glob Oncol 2018;4:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.United Nations . Human Development Indices and Indicators: 2018 Statistical Update. Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations; 2018. http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/2018_human_development_statistical_update.pdf. Accessed April 29, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boum Ii Y, Burns BF, Siedner M et al. Advancing equitable global health research partnerships in Africa. BMJ Glob Health 2018;3:e000868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Einhorn LH. A great IDEA: Celebrating 15 years of the International Development and Education Award. ASCO Connection, July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tierney WM, Nyandiko WN, Siika AM et al. “These are good problems to have …”: Establishing a collaborative research partnership in East Africa. J Gen Intern Med 2013;28(suppl 3):625–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Efstathiou JA, Bvochora‐Nsingo M, Gierga DP et al. Addressing the growing cancer burden in the wake of the AIDS epidemic in Botswana: The BOTSOGO collaborative partnership. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2014;89:468–475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Efstathiou JA, Heunis M, Karumekayi T et al. Establishing and delivering quality radiation therapy in resource‐constrained settings: The story of Botswana. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:27–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okello CD, Ddungu H, Omoding A et al. Capacity building for hematologic malignancies in Uganda: A comprehensive research, training, and care program through the Uganda Cancer Institute‐Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center collaboration. Blood Adv 2019;2(suppl 1):8–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neal C, Rusangwa C, Borg R et al. Cost of providing quality cancer care at the Butaro Cancer Center of Excellence in Rwanda. J Glob Oncol 2017;4:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.UNC Project ‐ Malawi . UNC School of Medicine Web site. https://www.med.unc.edu/medicine/infdis/malawi/. Accessed April 29, 2019.

- 18.Priority Partnership Locations: Moshi, Tanzania. Duke Global Health Institute Web site. https://globalhealth.duke.edu/priority‐partnership‐locations/moshi‐tanzania. Accessed April 29, 2019.

- 19.Razzano D, Hall A, Gardner JM et al. Pathology engagement in global health: Exploring opportunities to get involved. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2019;143:418–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.19th WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (April 2015). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015 https://www.who.int/medicines/publications/essentialmedicines/EML2015_8‐May‐15.pdf. Accessed April 29, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Access to Medicine Foundation . Access to Medicine Index 2018. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Access to Medicine Foundation; November 2018. https://accesstomedicinefoundation.org/media/uploads/downloads/5cb9b00e8190a_Access‐to‐Medicine‐Index‐2018.pdf. Accessed April 29, 2019. [Google Scholar]