Abstract

The aim of this study is to explore the effect of flavonoids from Rosa roxburghii Tratt (FRRT) on doxorubicin (DOX)-induced autophagy of myocardial cells. Primary isolation and culture of myocardial cells and H9C2 myocardial cell lines from 1 to 3-day-old rats were performed, myocardial cells were incubated using 5 μmol/L DOX and a cardiotoxicity model was established, intervention was conducted via FRRT, and the ultrastructure of myocardial cells was observed under a transmission electron microscope. The expressions of LC3-II and P62 proteins were detected through immunofluorescence and Western blotting. The ultrastructure showed a large quantity of autophagic vacuoles of the cells in DOX group with poor cell state. After the FRRT intervention, only a small quantity of autophagic vacuoles appeared in the myocardial cells, and there were many coarse microvilli on the cell surface. The expression of P62 protein was reduced in DOX group, while that in FRRT group was increased (p < 0.01). In conclusion, FRRT exerts a protective effect in the DOX-induced cardiotoxicity by down-regulating DOX-induced autophagy of myocardial cells.

Keywords: Autophagy, Flavonoids from Rosa roxburghii Tratt (FRRT), Doxorubicin, Myocardial cell

Introduction

Cancer is one of the prime reasons for global deaths, and about 9 million people died of cancer in 2016 (Abbafati et al. 2017). Anthracyclines are currently one of the most effective anticancer drugs. As one of the most common anthracyclines (Aramvash et al. 2017), doxorubicin (DOX) induces cell apoptosis and autophagy via different signaling pathways in tumor tissues or cancer cells, and it is effective in treating various cancers such as osteosarcoma, breast cancer, ovarian cancer, small cell lung cancer and Hodgkin lymphoma (Fong et al. 2012; Kalyanaraman et al. 2002). Anthracyclines have many side effects, the most common of which is cardiotoxicity (Angsutararux et al. 2015; Mitry and Edwards 2016). DOX is a first-line drug for cancer treatment, which has been restricted in clinical application owing to its cardiotoxicity (Cagel et al. 2017).

DOX-induced cardiotoxicity includes the generation of free radicals, calcium overload, mitochondrial dysfunction, cell apoptosis and autophagy (Vejpongsa and Yeh 2014). Studies have shown that apoptosis and autophagy play a significant role in the pathogenesis of cardiotoxicity (Bartlett et al. 2017; Gao et al. 2015; Tacar et al. 2015). As a process of self-degradation, autophagy provides survival advantages for cells under nutrient deficiency for a long time (Boya et al. 2013), which is very important for maintaining the balance of intracellular environment. Cells stimulate their self-degradation process to scavenge the aggregated proteins and impaired organelles (e.g., endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria) (Glick et al. 2010). Autophagy can be divided into 3 types according to different transfer ways of intracellular substances to lysosome: macroautophagy, microautophagy and molecular chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA). Autophagy mentioned in this paper refers to macroautophagy (Lin et al. 2015). LC3 is an autophagy marker, which can be divided into Type I and Type II. When autophagy occurs, LC3-I binds to phosphatidyl ethanolamine on the autophagosome membrane surface through ubiquitination-like modification to form LC3-II protein, which bind to each other and are always located on the intracellular autophagosome membrane, and their content is in direct proportion to the quantity of autophagic vacuoles (Gozuacik and Kimchi 2004). Thus, LC3-II is a symbolic protein of autophagy and a symbolic molecule of autophagosome, which directly reflects the occurrence degree of autophagy (Wei et al. 2012). When autophagy occurs, P62 binds to ubiquitinated proteins at first to form ubiquitinated agglomerates, which bind to LC3-II proteins on the autophagosome membrane to form a compound, then the compound is degraded in the autolysosome with declining P62 level. When autophagic activity is inhibited, P62 protein is continuously accumulated (Mathew et al. 2009). A study has confirmed that DOX can induce autophagic death of normal myocardial cells and gradually result in the formation of rat chronic heart failure. The autophagy inhibitor 3-methyladenine (3-MA) can mitigate the toxicity and cardiac dysfunction induced by DOX; furthermore, it can specifically inhibit the activities of Beclin-1 and LC3, restrict autophagic activity of myocardial cells, so as to improve DOX-induced myocardial lesions (Park et al. 2016). Drugs that prevent DOX-induced cardiomyopathy allow us to realize the full therapeutic potential of DOX, and the existing cardiomyopathy treatments have not achieved the expected success (Oliveira et al. 2013).

Flavonoids are a kind of small molecular compounds with high bioactivity and a very strong antioxidant. Originating in China, Rosa roxburghii Tratt is a kind of deciduous shrub famous for its highly nutritious fruit. Total flavonoid content is high in fresh fruit of R. roxburghii Tratt, being 11–12 times of that in ginkgo leaf, so it can be called as “king of flavonoids”. The average total flavonoid content in fresh fruit of R. roxburghii Tratt is 6.8 g/kg (He and Zhu 2011). It is reported that flavonoid compounds extracted from R. roxburghii Tratt are effective antioxidants (Zhang et al. 2005). The purity of FRT used in this paper is 73.85% with main compounds being catechin (34.26%) and quercetin (2.97%). Existing studies indicate that flavonoids in R. roxburghii Tratt fruit have important biological activities, such as anti-inflammation, expansion of coronary artery, control of blood pressure and protection of blood vessels. A study has verified that flavonoids from R. roxburghii Tratt (FRRT) can exert anti-apoptotic effect in the radiation (Xu et al. 2017). Our previous study showed that FRRT could induce cardiac functions of rats with heart failure (Li et al. 2018). Whether FRRT can exert its effect on cardiotoxicity of DOX by regulating autophagy? Thus, the aim of this study was to investigate the effect of autophagy on the cardiotoxicity of FRRT by culturing myocardial cells.

Materials and methods

Cell grouping

SD newly born rats were provided by the Animal Center of Xinxiang Medical University (SCXK 010-0002). This study was performed in strict accordance with the recom mendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD, USA). Eighth Edition, 2010. The animal use protocol has been reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Xinxiang Medical University. Myocardial cells were isolated from SD newly born rats and the minced myocardium was digested using mixed enzyme of 0.1 mg/mL type II collagenase and 0.125 mg/mL trypsin for 10 times, the centrifuged cells were digested and differentially adhered for 1 h in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM)-low glucose (Hyclone, Logan, Utah, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (Gibco), the supernatants were adsorbed out and uniformly spread in a 24-well plate, then cells were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified incubator at 5% CO2. After 24 h, the medium was replaced. At 72 h, cell density grew to 75%, obvious pulsation of myocardial cells could be observed under a microscope, and drugs were conducted in different groups.

Drug action time and concentration analysis

Myocardial cells after primary isolated culturing were incubated using 5 μmol/L DOX (doxorubicin hydrochloride for injection; Wanle Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China) for 1, 3, 6, 12, 18 and 24 h, respectively, and the most obvious time point for cell changes was recorded. On this basis, these cells were intervened with FRRTs (Concentration: 73%; provided by School of Pharmacy, Xinxiang Medical University; Patent No. ZL201010570876.1) of different concentrations in advance at different time. At 12, 24 and 36 h after myocardial cells were incubated using 40, 60 and 80 μg/mL FRRTs, respectively, DOX was added for another 12 h incubation. They were fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature, followed by the detection of LC3-II expression via immunofluorescence staining, cell observation and image acquisition under a laser scanning confocal microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Myocardial cells obtained after primary isolated culturing and H9C2 cell lines (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) were divided into three groups. No drug was added in the control group, and the cells were cultured in a conventional media for 42 h. Myocardial cells and cell lines in the DOX group were incubated for 12 h using 5 μmol/L DOX. Myocardial cells and cell lines were incubated in advance for 24 h using the screened 80 μg/ml FRRT in the FRRT group, and 5 μmol/L DOX was added for another 12 h inoculation.

Ultrastructure observation

After the treatment of H9C2 myocardial cells in each group was done, the cells were centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 10 min, fixed using 2% glutaraldehyde and placed at 4 °C to stay overnight, the next day, 2% glutaraldehyde was adsorbed out and washed using PBS for three times (5 min each time). It was fixed using 10 ml/L osmic acid, followed by gradient hydration via ethanol and acetone, saturation and epoxy resin embedding, and then ultrathin slice specimens were prepared, which were double stained using uranyl acetate and lead nitrate. Images were observed and acquired under H-7500 transmission electron microscope (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan).

Immunofluorescence single/double-labeling assay

Isolated primary myocardial cells were uniformly inoculated in a 24-well plate spread with slides, and then cultured at 37 °C in a humidified incubator at 5% CO2. The cells were treated through the conventional method, washed using PBS for 3 times and fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 20 min, and then washed using PBS for another 3 times (5 min each time), dried via 0.3% Triton X-100 at room temperature for 20 min, washed using PBS for 3 times (5 min each time), and sealed using 10% goat serum for 1 h. Mouse anti-cTnT antibody (1:500; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and rabbit anti-LC3-II antibody (1:500; Beyotime) mixtures, cTnT antibody (1:500; Abcam) and rabbit anti-P62 antibody (1:500; Boster, Wuhan, China) mixtures were added in each group for incubation overnight at 4 °C. After washing using PBS the next day, fluorescent second antibody (1:500) mixed by Cy3-labelled goat anti-rabbit IgG (H + L) and FITC-labelled goat anti-mouse IgG (H + L) antibodies were utilized for incubation at room temperature for 3 h away from light. After washing with PBS, the cells were incubated with 4’6-diamidino-2- phenylindole (DAPI) (Biosharp, Hefei, China) for 15 min away from light. Mounting was performed using anti-fluorescent quenching agent after washing with PBS. Negative control was set in the experiment, the blocking solution was used to replace primary antibody and other steps were ditto. Cells were observed and images were acquired under a FV-1000 laser scanning confocal microscope (Olympus).

Western blotting

After H9C2 myocardial cells in each group were treated, proteins were extracted using RIPA protein lysis buffer (Biosharp). Equal amounts of proteins were taken for each group, SDS-PAGE was conducted, and proteins were transferred to PVDF membrane, then blocked using TBS-T containing 5% skimmed milk powder for 1 h, after which LC3-II antibody (1:500; Beyotime), P62 antibody (1:500; Boster, Wuhan, China) and β-actin antibody (1:3000; Boster) were added at room temperature for 1 h, then incubated overnight at 4 °C. The next day, the membrane was washed using TBS-T, the proteins were incubated using HRP-labelled second antibody (1:3000) at room temperature for 2 h, the membrane was washed using TBS-T, followed by developing, exposure and photographing. A semi-quantitative analysis of average optical density was conducted via Image J software (UVP, LLC Upland, CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 16.0 software (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). Measured data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, one-way ANOVA was used for the comparison between groups, and p < 0.05 meant that the difference had statistical significance.

Results

FRRT rescued the myocardial cells from DOX-induced cell shrinkage and excessive autophagy

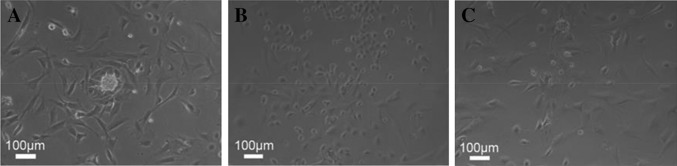

The results observed under a phase contrast microscope showed that primary isolated myocardial cells presented long fusiform shape or with many protuberances and they were under regular pulsation. In DOX group, most cells were shrunk and presented small round shape with high refraction, indicating a poor cell growth. After the intervention of FRRT, most cells were rescued from shrinkage and presented long fusiform shape or under multi-protuberance state (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Microstructures of primary isolated myocardial cells in three groups. a Control group; b DOX group; c FRRT + Dox group. Cell growth state intervened by FRRT was improved in comparison with that in the DOX group

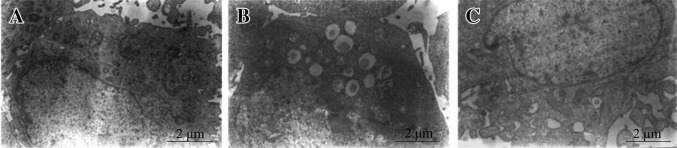

The results observed under a transmission electron microscope showed that a large quantity of autophagic vacuoles and lipofuscins appeared in the H9C2 myocardial cells in DOX group with poor cell states, namely excessive autophagy and aging state. No lipofuscin or autophagic vacuoles were formed in the control group, and organelles had normal structures. No lipofuscins but a small quantity of autophagic vacuoles were seen in myocardial cells in FRRT group, and other organelles presented normal structures with many coarse microvilli on the cell surface (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Ultrastructures of H9C2 myocardial cells in three groups. a Control group; b DOX group; c FRRT + Dox group. The quantity of intracellular autophagic vacuoles intervened by FRRT was reduced compared with the DOX group, and no lipofuscin was found

Screening the time for high expression of LC3-II in myocardial cells incubated using DOX

From the results of immunofluorescence microscopy, almost no LC3-II was detected at 1–6 h after primary myocardial cells were incubated using DOX, but it increased from 12 to 24 h, with the highest at 12 h (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Expression of LC3-II in primary myocardial cells incubated with DOX at different time by immunofluorescence detection. The results showed that the protein level of LC3-II was the highest at 12 h after cell incubation with DOX

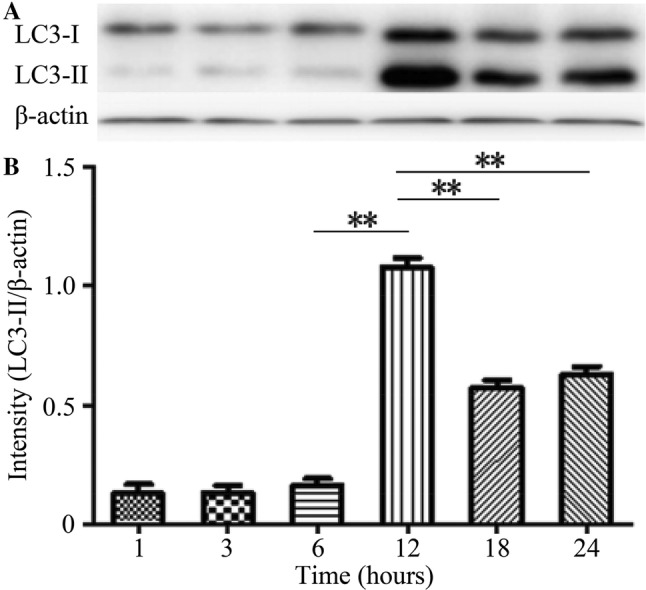

H9C2 myocardial cell lines were incubated using 5 μmol/L DOX for different time (1, 3, 6, 12, 18 and 24 h). According to the Western blotting results, at 12 h after cell incubation with DOX, LC3-II showed the highest expression level. However, at 12 h, LC3-II was almost not expressed in the first 3 time groups, and after then, LC3-II expression in the last 2 groups conferred a declining tendency. Therefore, the differences between 12 h group and the other 5 groups had statistical significance (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Expression of LC3-II in H9C2 cell lines incubated with DOX at different time by Western blotting. Based on the results, the protein level of LC3-II was the highest at 12 h after cell incubation with DOX

Effects of intervention of FRRTs with different concentrations on LC3-II expression in myocardial cells

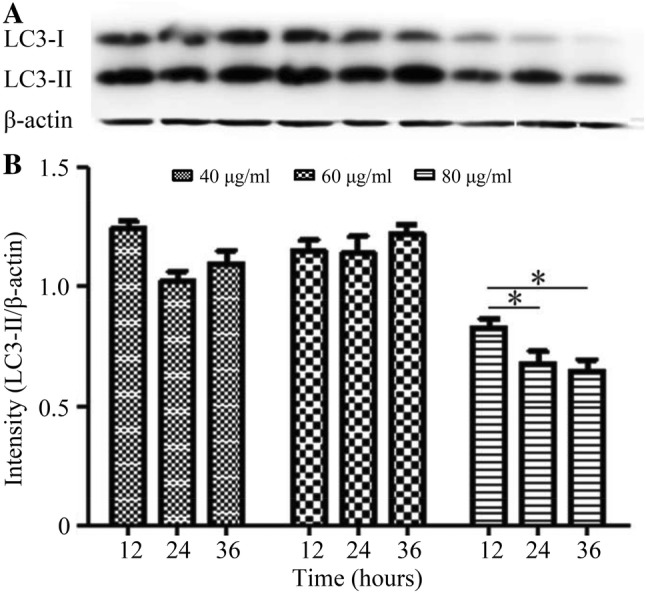

After H9C2 myocardial cells were incubated in advance using FRRTs with concentrations of 40, 60 and 80 μg/mL for 12, 24 and 36 h, and then incubated with 5 μmol/L DOX for 12 h, the cell proteins in these groups were extracted. The protein level of LC3-II was detected by Western blotting. The results showed that during 3 time periods when H9C2 myocardial cells were incubated with FRRT at the concentration of 80 μg/mL, the expression levels of LC3-II were obviously reduced in comparison with those in the same time periods at the concentrations of 40 and 60 μg/mL. Relative to LC3-II expressions at 12 h after H9C2 myocardial cells were incubated using 80 μg/mL FRRT, those at 24 h and 36 h were reduced, and intergroup differences had statistical significance (p < 0.05), but the difference between 24 and 36 h group was not statistically significant (p > 0.05) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Expression of LC3-II in DOX-intoxicated H9C2 myocardial cells intervened by FRRTs with different concentrations by Western blotting. At 12 h after H9C2 myocardial cells were incubated with FRRT at the concentration of 80 μg/mL, the expression of LC3-II declined, and intergroup difference was of statistical significance (*p < 0.05)

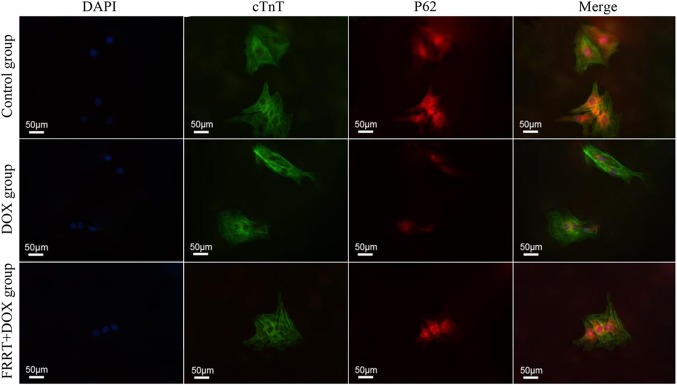

Detection of LC3-II and P62 expressions in primary isolated myocardial cells

The detection results showed that LC3-II protein was dispersed in the cytoplasm. LC3-II presented weak positive expression in the control group, LC3-II protein was mainly expressed in myocardial cytoplasm and around the nucleus, and the expression of LC3-II in FRRT group was not as obvious as that in DOX group (Fig. 6). P62 protein was expressed in cytoplasm. P62 presented weak positive expression in most cytoplasms in the control group, and it was expressed in a small number of cells with a low expression level. P62 was obviously expressed in some cells in FRRT group (Fig. 7).

Fig. 6.

Expression of LC3-II in three groups of primary myocardial cells by immunofluorescence double-labeling assay. The expression of LC3-II in the cells intervened by FRRT was reduced in comparison with that in DOX group. DAPI, showing nuclei; cTnT, positive expression of cTnT; LC3-II, positive expression of LC3-II; Merge, co-expression of cTnT and LC3-II

Fig. 7.

Expression of P62 in three groups of primary myocardial cells by immunofluorescence double-labeling assay. The expression of P62 in the cells intervened by FRRT was increased relative to that in DOX group. DAPI, showing nuclei; cTnT, positive expression of cTnT; P62, positive expression of P62; Merge, co-expression of cTnT and P62

Expressions and semi-quantitative analysis of LC3-II and P62

Western blotting and semi-quantitative analysis results showed that the LC3-II expression was obviously elevated in DOX group, while that in FRRT group was reduced, but it was slightly higher than that in the control group, and differences between the groups had statistical significance (p < 0.01). Compared with the control group, P62 expression in DOX group and FRRT group was reduced (p < 0.01), but its expression in FRRT group was slightly higher than that in DOX group (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Expressions of LC3-II and P62 in three groups of H9C2 myocardial cells by Western blotting and semi-quantitative analysis. According to the detection results, the expression of LC3-II in the cells intervened by FRRT was reduced, while P62 expression was increased compared with those in DOX group, and intergroup difference was of statistical significance (**p < 0.01)

Discussion

DOX-induced cardiotoxicity is a very serious disease. However, effective therapeutic and preventive treatment methods have not been clinically found yet (Park et al. 2012). Flavonoids have strong in vitro antioxidation effect and Epimedium flavonoid injection can exert the anti-myocardial ischemia effect by improving the ST-T change in electrocardiogram (ECG) (Huang et al. 2005). Total flavonoids from ginkgo biloba can obviously suppress oxidative stress of the organism and inhibit excessive autophagy (reduce Beclin-1 level and LC3 II/I ratio) (Shen et al. 2016). It has been verified that total antioxidant capacity in the organism has a direct effect on the survival status of myocardial cells. Intracellular reactive oxygen can promote the occurrence of autophagy, while the enhanced antioxidant capacity can inhibit excessive cell autophagy. Fruit of R. roxburghii Tratt is rich in flavonoids. Autophagy exerts dual effects in the treatment and progression of cardiotoxicity. Some studies indicate that DOX up-regulates cardiac autophagic action, which helps DOX to induce the pathogenesis of cardiotoxicity (Dimitrakis et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2014; Xu et al. 2012). Xu et al. (2012) pointed out that DOX activated Beclin-1 and increased autophagy in myocardial cells of newly born rats. Nevertheless, some studies have supported the viewpoint that DOX induced cardiotoxicity by inhibiting autophagy (Kawaguchi et al. 2012; Sishi et al. 2013). Kawaguchi et al. (2012) reported that DOX inhibited autophagy by reducing AMPK phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of ULK1. These contradictory findings can largely be attributed to the used animal model type and experimental conditions (Dirks-Naylor 2013). As reported in this study, DOX treatment inhibits autophagy in the mouse model, but this autophagy is activated in the rat model.

In this study, FRRT controlled DOX-induced cardiotoxicity by inhibiting autophagy. The autophagy of myocardial cells was up-regulated due to DOX-induced cardiotoxicity, which was consistent with the previous studies (Dimitrakis et al. 2012; Xu et al. 2012). Primary isolated myocardial cells and H9C2 myocardial cell lines were utilized in the present study, and we found that a large number of autophagic vacuoles appeared in the myocardial cell submicrostructure due to DOX, LC3-II expression was increased and P62 expression was decreased in myocardial cells, which was identical with the results reported by Shen et al. (2016). In addition, cell adhesive capacity was degraded, and mitochondrial cristae were decreased and dissolved. Hence, FRRT could improve submicrostructure of myocardial cells, the autophagic vacuoles in the cells obviously reduced in comparison with those under DOX treatment, but the microvilli on the cell surface were obvious and coarse. The expression of autophagic protein LC3-II was down-regulated, while the expression of P62 was up-regulated, indicating that FRRT can inhibit DOX-induced autophagy of myocardial cells. Our study has confirmed that FRRT can be considered as a promising drug to relieve DOX-induced cardiotoxicity. Previous research from our group has demonstrated that FRRT is a good radioprotectant. Irradiation treatment of FRRT-intervened cells can remarkably improve the survival rate of cells (Xu et al. 2014). FRRT can exert the anti-radiative effect via its anti-apoptotic effect. In comparison with the irradiation group, the expressions of Bax/Bcl-2 and p-p53/p53 were reduced in the group of thymocytes pretreated with FRRT, so FRRT enhanced the radioprotective effect by inhibiting cell apoptosis (Xu et al. 2016). FRRT could improve the DOX-induced cardiotoxicity through its anti-apoptotic effect. Compared with those in the DOX group, the expressions of Bax and p53 were reduced, while the expression of Bcl-2 was increased in myocardial cells pretreated with FRRT, and FRRT mitigated cardiotoxic effect of DOX by inhibiting the cell apoptosis (Park et al. 2012). According to our research results, it was found that FRRT, when used to intervene myocardial cells, could reduce autophagy and apoptosis of myocardial cells caused by DOX and play a certain protective effect.

DOX facilitates autophagy of myocardial cells by significantly increasing the content of autophagy-related molecules LC3-II and decreasing the content of P62, respectively. FRRT can play a role in inhibiting autophagy by down-regulating the content of LC3-II and up-regulating that of P62. In other words, FRRT exerts its protective effect on myocardial cells by inhibiting autophagy, which provides a new cytological basis for reasonable clinical development and application of FRRT in treating DOX-induced myocardial diseases. However, through which signaling pathways FRRT regulates the autophagy and how it exerts its protective effect should be further explored. Therefore, FRRT is expected to be used for preventing or treating DOX-induced cardiotoxicity.

Acknowledgements

This study was financially supported by the Foundation of Xinxiang City Key Technology Research Project, Henan Province, China (No. ZG15015).

Authors’ contribution

Xinhua Cai designed, analyzed the experiments. and wrote the manuscript. Huifang Yuan performed the experiments and co-wrote the manuscript. Yiru Wang and Hui Chen analyzed some experiment data and co-wrote the manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Abbafati C, Abbas KM, Abd-Allah F, Abera SF, Aboyans V, Adetokunboh O, Afshin A, Agrawal A, et al. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific mortality for 264 causes of death, 1980–2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390:1151–1210. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32152-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angsutararux P, Luanpitpong S, Issaragrisil S. Chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity: overview of the roles of oxidative stress. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2015;2015:795602. doi: 10.1155/2015/795602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aramvash A, Rabbani Chadegani A, Lotfi S. Evaluation of apoptosis in multipotent hematopoietic cells of bone marrow by anthracycline antibiotics. Iran J Pharm Res. 2017;16:1204–1213. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett JJ, Trivedi PC, Pulinilkunnil T. Autophagic dysregulation in doxorubicin cardiomyopathy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2017;104:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2017.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boya P, Reggiori F, Codogno P. Emerging regulation and functions of autophagy. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:713–720. doi: 10.1038/ncb2788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cagel M, Grotz E, Bernabeu E, Moretton MA, Chiappetta DA. Doxorubicin: nanotechnological overviews from bench to bedside. Drug Discov Today. 2017;22:270–281. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2016.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrakis P, Romay-Ogando MI, Timolati F, Suter TM, Zuppinger C. Effects of doxorubicin cancer therapy on autophagy and the ubiquitin-proteasome system in long-term cultured adult rat cardiomyocytes. Cell Tissue Res. 2012;350:361–372. doi: 10.1007/s00441-012-1475-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirks-Naylor AJ. The role of autophagy in doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Life Sci. 2013;93:913–916. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2013.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong MY, Jin S, Rane M, Singh RK, Gupta R, Kakar SS. Withaferin A synergizes the therapeutic effect of doxorubicin through ROS-mediated autophagy in ovarian cancer. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e42265. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Xu Y, Hua S, Zhou S, Wang K. ALDH2 attenuates Dox-induced cardiotoxicity by inhibiting cardiac apoptosis and oxidative stress. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:6794–6803. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick D, Barth S, Macleod KF. Autophagy: cellular and molecular mechanisms. J Pathol. 2010;221:3–12. doi: 10.1002/path.2697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gozuacik D, Kimchi A. Autophagy as a cell death and tumor suppressor mechanism. Oncogene. 2004;23:2891–2906. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He WP, Zhu XY. Research progress on bioactive ingredients and food development of roxburghia roxburghii. Guangxi Light Ind. 2011;156:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Huang XL, Zhang XJ, Wang W, Zhou YW. Effects of total flavonoids of epimedium injection on experimental myocardial ischemia in rats incurred by pituitrin. China J Tradit Chin Med Pharm. 2005;20:533–534. [Google Scholar]

- Kalyanaraman B, Joseph J, Kalivendi S, Wang S, Konorev E, Kotamraju S. Doxorubicin-induced apoptosis: implications in cardiotoxicity. Mol Cell Biochem. 2002;234–235:119–124. doi: 10.1023/A:1015976430790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi T, Takemura G, Kanamori H, Takeyama T, Watanabe T, Morishita K, Ogino A, Tsujimoto A, Goto K, Maruyama R, Kawasaki M, Mikami A, Fujiwara T, Fujiwara H, Minatoguchi S. Prior starvation mitigates acute doxorubicin cardiotoxicity through restoration of autophagy in affected cardiomyocytes. Cardiovasc Res. 2012;96:456–465. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D, Wang YD, Cai XH, Chen JZ, Lv YZ, Liang QK. Effects of roxb flavone on cardiac structure, function and expression of ventricular signal transducers and transcription activator 1 protein in heart failure rats. J Xinxiang Med Univ. 2018;35:558–562. [Google Scholar]

- Lin L, Liu X, Xu J, Weng L, Ren J, Ge J, Zou Y. High-density lipoprotein inhibits mechanical stress-induced cardiomyocyte autophagy and cardiac hypertrophy through angiotensin II type 1 receptor-mediated PI3K/Akt pathway. J Cell Mol Med. 2015;19:1929–1938. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew R, Karp CM, Beaudoin B, Vuong N, Chen G, Chen HY, Bray K, Reddy A, Bhanot G, Gelinas C, Dipaola RS, Karantza-Wadsworth V, White E. Autophagy suppresses tumorigenesis through elimination of p62. Cell. 2009;137:1062–1075. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitry MA, Edwards JG. Doxorubicin induced heart failure: phenotype and molecular mechanisms. IJC Heart Vasc. 2016;10:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcha.2015.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira MS, Melo MB, Carvalho JL, Melo IM, Lavor MS, Gomes DA, de Goes AM, Melo MM. Doxorubicin cardiotoxicity and cardiac function improvement after stem cell therapy diagnosed by strain echocardiography. J Cancer Sci Ther. 2013;5:52–57. doi: 10.4172/1948-5956.1000184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park E, Ahn BH, Kim HJ, Park JH, Koo SY, Kwak HS, Park HS, Kim DW, Song M, Yim HJ, Seo DO, Kim SH. NecroX-7 prevents oxidative stress-induced cardiomyopathy by inhibition of NADPH oxidase activity in rats. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2012;263:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2012.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JH, Choi SH, Kim H, Ji ST, Jang WB, Kim JH, Baek SH, Kwon SM. Doxorubicin regulates autophagy signals via accumulation of cytosolic Ca2+ in human cardiac progenitor cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:1680–1693. doi: 10.3390/ijms17101680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen XZ, Wang L, Fang YH. Yinxing leaf total flavonoid mitigates myocardial ischemia and reperfusi on injury via regulating autophagy. Anhui Med Pharm J. 2016;20:1065–1067. [Google Scholar]

- Sishi BJ, Loos B, van Rooyen J, Engelbrecht AM. Autophagy upregulation promotes survival and attenuates doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Biochem Pharmacol. 2013;85:124–134. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tacar O, Indumathy S, Tan ML, Baindur-Hudson S, Friedhuber AM, Dass CR. Cardiomyocyte apoptosis vs autophagy with prolonged doxorubicin treatment: comparison with osteosarcoma cells. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2015;67:231–243. doi: 10.1111/jphp.12324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vejpongsa P, Yeh ET. Prevention of anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity: challenges and opportunities. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:938–945. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.06.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Wang XL, Chen HL, Wu D, Chen JX, Wang XX, Li RL, He JH, Mo L, Cen X, Wei YQ, Jiang W. Ghrelin inhibits doxorubicin cardiotoxicity by inhibiting excessive autophagy through AMPK and p38-MAPK. Biochem Pharmacol. 2014;88:334–350. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2014.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei K, Wang P, Miao CY. A double-edged sword with therapeutic potential: an updated role of autophagy in ischemic cerebral injury. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2012;18:879–886. doi: 10.1111/cns.12005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Chen K, Kobayashi S, Timm D, Liang Q. Resveratrol attenuates doxorubicin-induced cardiomyocyte death via inhibition of p70 S6 kinase 1-mediated autophagy. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012;341:183–195. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.189589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu P, Zhang WB, Cai XH, Lu DD, He XY, Qiu PY, Wu J. Flavonoids of Rosa roxburghii Tratt act as radioprotectors. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:8171–8175. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.19.8171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu P, Cai X, Zhang W, Li Y, Qiu P, Lu D, He X. Flavonoids of Rosa roxburghii Tratt exhibit radioprotection and anti-apoptosis properties via the Bcl-2(Ca2+)/Caspase-3/PARP-1 pathway. Apoptosis. 2016;21:1125–1143. doi: 10.1007/s10495-016-1270-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu P, Liu X, Xiong X, Zhang W, Cai X, Qiu P, Hao M, Wang L, Lu D, Zhang X, Yang W. Flavonoids of Rosa roxburghii Tratt exhibit anti-apoptosis properties by regulating PARP-1/AIF. J Cell Biochem. 2017;118:3943–3952. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang XL, Qu WJ, Sun B, Hu B. Antioxidant effect of flavonoids from cili in vitro. Nat Prod Res and Dev. 2005;17:396–400. [Google Scholar]