Abstract

Background and study aims Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) is increasingly used for the treatment of large colonic polyps (≥ 20 mm). A drawback of EMR is local adenoma recurrence. Therefore, we studied the impact of argon plasma coagulation (APC) of the EMR edge on local adenoma recurrence.

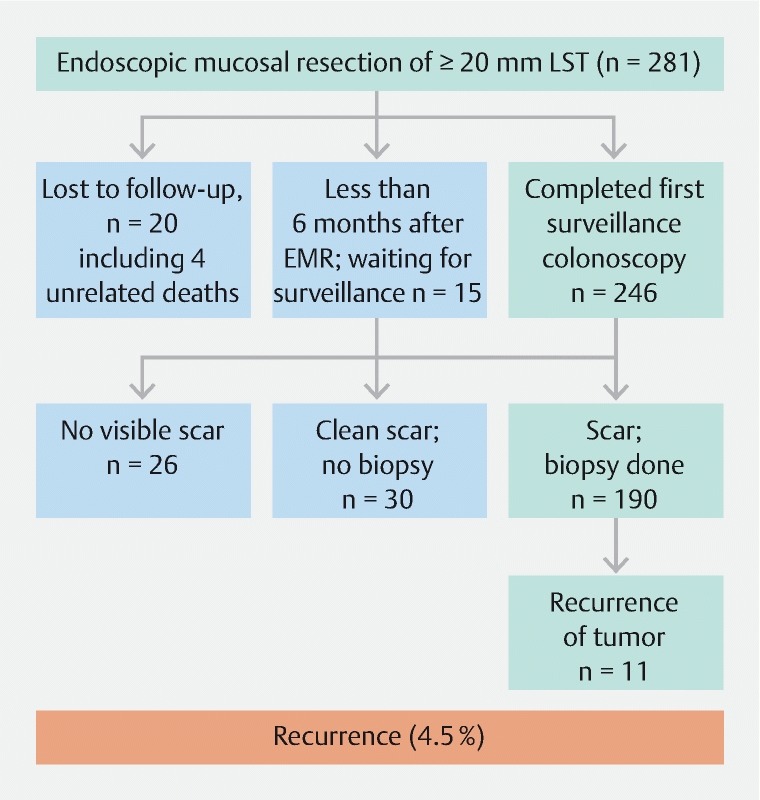

Patients and methods This was a retrospective study of patients with laterally spreading tumors (LST) ≥ 20 mm, who underwent EMR from January 2009 to August 2018 and follow-up endoscopic assessment. A cap-fitted endoscope was used to assess completeness of resection by systematically inspecting the EMR defect for any macroscopic disease. This was followed by forced APC of the resection edge followed by clip closure of the defect. Surveillance colonoscopy was performed at 6 months after resection to detect recurrence.

Results Two hundred forty-six patients met the inclusion criteria. Most were female (53 %) and white (80 %), with a Median age of 64 years. Median polyp size was 35 mm (interquartile range, 30–45 mm). Most polyps were located in the right colon (77 %) and were removed by piecemeal EMR (70 %). Eleven patients (5 %) had residual tumor at the resection site.

Conclusions We observed low adenoma recurrence after argon plasma coagulation of the EMR edge with a cap fitted colonoscope in patients with LST ≥ 20 mm of the colon, which requires further validation in a randomized controlled study.

Introduction

Traditionally, patients with large colonic polyps have been referred for surgery, which carries significant morbidity and mortality 1 2 . Even with the advent of endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) as a safe and effective treatment of such large lesions, the referral rate for surgery remains high 3 4 5 . Cost analyses demonstrated that EMR is cheaper than endoscopic submucosal dissection and surgery 6 7 8 9 .

One of the arguments against EMR of large polyps (unlike surgery and endoscopic submucosal dissection) is a high rate of both incomplete resection and local recurrence. Most studies demonstrated local recurrence rates of 15 % to 30 % in patients with large colonic polyps 10 11 12 . Several polyp characteristics are linked with an increased risk of local recurrence after EMR, such as lesion size and morphology, prior intervention, presence of high-grade dysplasia (HGD), EMR technique, and margin positivity 13 14 15 . Nonetheless, whether ancillary maneuvers such as systematic observation of the EMR site with a cap fitted colonoscope followed by ablation of the edge with APC can lead to a decrease in the recurrence rate has yet to be well studied.

Previously, we reported on our preliminary experience in performing EMR for complex colon polyps as an alternative to surgery using a standardized protocol since 2009 16 . As part of that protocol, after documenting absence of macroscopic disease at the EMR edge and base using a cap-fitted endoscope, we applied argon plasma coagulation (APC) to the resection site. Our aim was to determine the impact of APC of the EMR edge on local colonic adenoma recurrence.

Patients and methods

Patients

This was a retrospective study of consecutive patients with large laterally spreading tumors (LSTs) of the colon (≥ 20 mm) who underwent EMR using a standardized protocol from January 2009 to August 2018 at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. Ethical approval of this study was obtained from the MD Anderson Institutional Review Board. Reasons for exclusion included patients with pedunculated polyps and sessile tumors, confirmed cancers that that were referred to us as benign tumors, lesions with extensive tethering to the colon wall, and lesions that could not be resected due to challenging endoscopic access.

Procedures

One endoscopist performed all the steps in the procedure: clinic visits to counsel the patients, with education about EMR using a dedicated YouTube channel; EMR following a standard protocol; discharge of patients after standard recovery; close follow-up examination with email communication during the first 5 days after the procedure; and surveillance colonoscopy at 6 and 18 months after EMR 16 .

Patients with a Boston Bowel Preparation Scale score of 8 or 9 underwent EMR using a high-definition cap-fitted endoscope (CF-H180AL/I, CF-Q180AL/I, or CF-HQ190; Olympus, Center Valley, Pennsylvania, United States) and lift-and-cut technique under sedation or anesthesia. Prior to the start of the resection, each lesion was examined carefully for features of deep submucosal cancer (Narrow Band Imaging International Colorectal Endoscopic classification III). Resection was not performed in patients with obvious cancerous lesions, even though they were designated as benign at referral. In cases where EMR is forecasted to be technically difficult, a colorectal surgeon was consulted prior to the procedure to assess risk. Saline with either indigo carmine or methylene blue with or without epinephrine was used for dynamic submucosal injection. Snare resection was performed using a microprocessor-controlled generator (ENDO CUT Q; Erbe USA, Marietta, Ga [effect 3; duration, setting 1; interval, settings 3–5]). After each resection, the resection base was examined before proceeding with the next resection. Additional fluid was injected if necessary before proceeding with subsequent resections. Bleeding during the procedure was controlled with hemostatic forceps (Olympus America, Melville, New York, United States [soft coagulation, effect 4, 60–80 W]). The process was repeated until all visible tissue was removed. Cold biopsy avulsion was used to remove tethered polyp (2009 to 2014); hot biopsy avulsion (ENDO CUT I [effect 1; duration, setting 1; interval, setting 1]) was used to remove small amounts of neoplastic tissue that could not be removed with a snare resection (2014 to 2018).

Completeness of resection was documented by systematically inspecting the entire edge with the endoscope cap touching the edge and taking photos of overlapping areas. This was followed by systematic examination of the resection base. Completeness of resection was defined as absence of any visible polyp in the resection base and edge and documentation of a round mucosal pit pattern at the resection edge.

APC was applied starting at one point on the resection edge and going around it to create a deep burn with brown discoloration of the entire edge using forced coagulation at 30 to 35 W and 0.8 L per minute flow. In addition, APC was applied to any areas in the resection base from which tiny residual polyp was removed using biopsy forceps. Once again, photos of overlapping areas of the ablated resection edge around the site were taken. Injection of tattoo (SPOT; GI Supply, Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania, United States) was applied for lesions between proximal ascending colon and rectosigmoid colon. Attempts were made to close any EMR defects with clips.

Surveillance

Patients were instructed to send messages to the endoscopist via e-mail or an electronic health record communication tool for the first 5 days after EMR to provide information about their progress; some patients had the endoscopist’s cell phone number and could call if they experienced any complications. On days 5 to 7, the endoscopist contacted the patients by phone to inform them of their pathology results and inquire about any complications. Surveillance colonoscopy was performed at 6 and 18 months after EMR by the same endoscopist in the majority of cases. During surveillance colonoscopy, the EMR scar was carefully examined using white light and narrow band imaging (NBI)as well as near-focus function of the endoscope and multiple photos of the scar site were taken. Biopsies of the EMR scars were routinely done except in patients with smooth scars and round mucosal pit pattern. Recurrence of adenoma identified during surveillance was managed using cold or hot biopsy avulsion followed by APC and clip closure.

Data collection and analysis

Patient data were collected retrospectively from medical charts and endoscopy reports using natural language processing 17 . Collected variables pertaining to medical history included age, race, sex, body mass index, and use of anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy before EMR. Also, whether the patient was self-referred for EMR, was referred by an endoscopist, or had EMR during the initial screening procedure was recorded.

At the time of EMR, endoscopic data were entered prospectively into a structured and formatted endoscopy report (EndoWorks; Olympus, and later Provation, Minneapolis, Minn). Photographic documentation of the endoscopic procedure with the EMR phases was done with a minimum of 20 photos for each lesion (maximum, 71 photos). Moreover, the majority of resections in our study were videotaped and posted on YouTube for educational purposes. Follow-up endoscopy was performed with imaging of the site of the prior EMR scar.

The number of polyps is equal to the number of patients, as we accounted for the largest lesion. Data relating to polyps were extracted from endoscopy and histopathology reports. Collected variables were: 1) the location, size, and morphology of the polyp; 2) ease of accessing the polyp endoscopically; 3) presence of HGD; 4) local polyp recurrence; and 5) complications.

Local recurrence was defined as residual polyp at the site of the original resection (histologically confirmed as adenoma) at the time of surveillance endoscopy. Clean, flat scars with no visible residual polyp upon white light, NBI, and near-focus examination were considered to be free from recurrence; biopsies were not routinely done to document clean scars without recurrent polyps 18 . Patients in whom no scar was visible despite careful examination of the area were also considered to be free of recurrence.

Complications were defined as those that required hospitalization, blood or blood product transfusions, endoscopic intervention, or surgery for management of abdominal pain, bleeding, or perforation.

Study endpoint

The primary endpoint was presence of endoscopically visible residual neoplastic tissue at the resection site that was histologically confirmed as adenoma at first surveillance endoscopy.

Data analysis

Categorical variables were summarized using frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables were summarized using Median values and interquartile ranges (IQRs). Logistic regression analysis was performed to assess the impact of patient and procedure factors on recurrence. P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using the SAS software program (version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, United States).

Results

Patients

Two hundred and forty-six consecutive patients with ≥ 20 mm LST who underwent EMR followed by surveillance colonoscopy to check the scar site for recurrence comprise the study cohort. One hundred thirty-one patients were female (53 %). Most of the patients were white (197 [80 %]), and the patients’ Median age was 64 years (IQR, 55–70 years). Patient and polyp characteristics are summarized in Table 1 .

Table 1. Patient and polyp characteristics.

| Characteristic | Number of patients (%) |

| Median age, years (IQR) | 64 (55–70) |

| Female sex | 131 (53) |

| Race | |

|

197 (80) |

|

21 (9) |

|

8 (3) |

|

6 (2) |

|

14 (6) |

| Referral type | |

|

34 (14) |

|

212 (86) |

| Anesthesia type | |

|

97 (39) |

|

78 (32) |

|

71 (29) |

| Endoscopic access | |

|

160 (65) |

|

86 (35) |

| Polyp location | |

|

65 (26) |

|

81 (33) |

|

50 (20) |

|

18 (7) |

|

14 (6) |

|

18 (7) |

| Median polyp size, mm (IQR) | 35 (30–45) |

| EMR type | |

|

172 (70) |

|

74 (30) |

| Polyp pathology | |

|

79 (32) |

|

77 (31) |

|

67 (27) |

|

14 (6) |

|

9 (4) |

| HGD | 81 (33) |

| Complications | 10 (4) |

IQR, interquartile range; EMR, endoscopic mucosal resection; HGD, high-grade dysplasia

EMR of polyps

Median size of polyps was 35 mm (IQR, 30–45 mm). Most of the polyps were located in the right colon (189 [77 %]). The endoscopist removed 172 polyps (70 %) using piecemeal EMR, whereas the 74 (30 %) were removed using en bloc EMR. Median total EMR procedure time was 60 minutes (IQR, 47–79 minutes).

EMR complications

Eight patients developed delayed bleeding, one patient developed perforation, two patients required hospitalization, and none required emergency surgery or died from the procedure.

Seventeen patients did not have clip closure of the lesion edges after successful EMR; one (6 %) of them developed excessive bleeding after EMR. Among patients who had clip closure (n = 229), nine patients had adverse events: seven (3 %) had postprocedural bleeding, six of these had spontaneous resolution of the bleeding and only one case required clip replacement; one had a small perforation that was closed successfully during the procedure; and one experienced respiratory difficulty after the procedure. Two of the patients that had post-EMR bleeding required hospitalization.

Pathology of polyps

Pathology of the 246 lesions included the following: 79 polyps (32 %) were tubular adenomas, 77 (31 %) were tubulovillous adenomas, 14 (6 %) were villous adenomas, 67 (27 %) were serrated adenomas, and 9 (4 %) were adenocarcinoma. Eighty-one polyps (33 %) had evidence of HGD in addition to the adenomatous features.

Local recurrence

All of the patients in our cohort underwent follow-up colonoscopy at 6 months after EMR. The physician found the EMR scar and performed biopsy analysis of it in 190 patients. In 30 patients with a smooth EMR scar and normal round mucosal pit pattern, the biopsies were deferred. Twenty-six patients had no detectable scar from the initial EMR. Eleven patients (5 %) had residual tumor at the resection site at the 6-month follow-up colonoscopy ( Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1 .

Flowchart of patients with > 20-mm colon LSTs who underwent EMR followed by argon plasma coagulation.

Characteristics of the original polyps in patients who had local recurrence are listed in Table 2 . All patients who had recurrences had undergone piecemeal EMR. Two of the patients underwent previous attempts at polyp resection that led to tethering of the polyp to the colon wall. Eight of these lesions were in the right colon, and three were in the rectum. Four of the patients who had local recurrence had HGD in the original polyp. No complications occurred during removal of the initial lesion in these 11 patients. Results of logistic regression analysis performed to assess the association of patient and polyp characteristics with recurrence revealed that only older age was associated with increased risk of local recurrence (odds ratio, 1.09 [95 % confidence interval, 1.02–1.17]; P = .013).

Table 2. Characteristics of the original polyps in patients who had local recurrence (n = 11).

| Characteristic | Number of patients (%) |

| Median age, years (IQR) | 73 (68–75) |

| Piecemeal EMR | 11 (100) |

| Tethering to the colon wall | 2 (18) |

| Median time of procedure, minutes (IQR) | 63 (41–80) |

| Endoscopic access | |

|

6 (55) |

|

5 (46) |

| Paris classification | |

|

9 (82) |

|

2 (18) |

| Polyp location | |

|

8 (73) |

|

3 (27) |

| Median polyp size, mm (IQR) | 35 (25–50) |

| Polyp pathology | |

|

5 (46) |

|

3 (27) |

|

0 (0) |

|

3 (27) |

|

0 (0) |

| HGD | 4 (36) |

IQR, interquartile range; EMR, endoscopic submucosal resection; HGD, high-grade dysplasia

Features of locally recurrent lesions

Recurrent lesions were visible in 10 of 11 patients who had local recurrence. The sizes of the visible recurrent lesions ranged from 3 to 4 mm. Only one lesion required repeat EMR. Among the patients who had local recurrence, 10 had tubular adenoma and one had serrated adenoma. HGD was present in two patients.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that the local colon adenoma recurrence rate in our cohort of patients with ≥ 20-mm colon LSTs managed using cap-fitted colonoscopy with EMR and ablation of the resection edge with APC was low (4.5 %). This adenoma recurrence rate was much lower than 16.0 % to 32 % reported in the literature on traditional EMR for non-pedunculated polyps ( Table 3 ) 3 10 12 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 .

Table 3. Summary of colon EMR studies for non-pedunculated lesions.

| Study | Country | Size of polyp (mm) | Total no. of patients | Piecemeal EMR | No. of patients with follow-up | Recurrence (%) |

| Moss et al. (2011) 3 | Australia | Median, 30 (IQR, 25–40) | 479 | 479 | 328 | 67 (20.4 %) |

| Buchner et al. (2012) 27 | USA | mean, 23 (SD, 13) | 274 | 132 | 135 | 36 (27 %) |

| Carvalho et al. (2013) 28 | Portugal | Median, 30 (IQR, 20–35) | 71 | 71 | 71 | 16 (22.2 %) |

| Knabe et al. (2014) 12 | Germany | Mean, 33 (range, 20–100) | 252 | 223 | 183 | 58 (31.7 %) |

| Maquire et al. (2014) 29 | USA | Mean, 28 (SD, 11) | 231 | 231 | 160 | 38 (23.8 %) |

| Moss et al. (2015) 10 | Australia | Median, 30 (IQR, 25–40) | 1,134 | – | 799 | 128 (16.0 %) |

| Sidhu et al. (2016) 30 | Australia | Median, 35 (IQR, 25–45) | 2,675 | 2,308 | 1,910 | 312 (16.3 %) |

| Zhan et al. (2016) 31 | Germany | Mean, 37.2 (SD, 19.6) | 129 | 88 | 129 | 34 (26.3 %) |

| Tate et al. (2017) 24 | Australia | Median, 35 (IQR, 30–45) | 1,178 | 1,178 | 1,178 | 228 (19.4 %) |

| Barosa et al. (2018) 32 | UK | Mean, 35 (SD, 17) | 316 | – | 316 | 65 (20.6 %) |

| Current study | USA | Median, 35 (IQR, 30–45) | 246 | 172 | 246 | 11 (4.5 %) |

Our large cohort study of 246 patients who underwent APC supports the observations in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of 21 patients with > 1.5-cm sessile polyps demonstrating that APC of a resection edge free from macroscopic disease reduces local recurrence rate; the recurrence rate in the APC treated group was 10 % 19 . We postulate that routine APC ablation of EMR defects using cap fitted colonoscope removes microscopic residual adenoma at the resection edge that is not identified by the endoscopist as shown previously, 20 which accounts for the low recurrence rate in our study (4.5 %). A recent RCT demonstrated significant reduction in adenoma recurrence in patients who underwent ablation of post-EMR defects using snare tip soft coagulation 21 . This method of snare tip coagulation is an attractive option given its simplicity and ready availability, with no additional costs incurred. However, APC being a non-contact modality offers the advantage of ablating areas that may be difficult to do with snare tip coagulation. Currently, no RCTs in the literature have compared use of different ablation techniques to reduce polyp recurrence after EMR.

Concerns about use of APC include variable arching of the electrosurgical current from the catheter to the tissue, with the potential for excessive injury that may predispose patients to complications such as bleeding and perforation, resulting in a lack of the desired effect 22 23 . However, in our study, we have not observed any complication related to the application of APC such as perforation or postpolypectomy syndrome. We postulate that using a cap at the end of the endoscope and keeping the tip of the cap just above the tissue allows for fixing the distance from the APC catheter to the tissue, thereby minimizing variable arching of the electrosurgical current from the catheter to the tissue.

Recently, researchers developed and validated several scoring systems for local recurrence of large polyps 14 15 24 . HGD, size of the lesion, number of polyps, and occurrence of bleeding during EMR are independent predictors of recurrence in those systems. In the current study, we did not find an association between these factors and recurrence. We attribute this to the small number of local recurrences in our cohort. In contrast, we did observe a significant association between older patient age and local recurrence ( P = .004). This finding is similar to that reported by Pommergaard et al 25 . Also, authors reported that piecemeal EMR was associated with a greater risk of local recurrence than was en bloc EMR 11 26 . However, due to the small number of local recurrences in our study, all of which occurred after piecemeal EMR, we were not able to draw any meaningful conclusions.

Our study had notable strengths. For example, one endoscopist performed all of the EMRs following the same protocol. This prevented discrepancy in findings that can occur with use of more than one endoscopist. In addition, we included only patients with large polyps to decrease the effect of polyp size as a major confounding factor. Furthermore, the endoscopist communicated via email or telephone to assess patients for complications after EMR. Finally, the structured form used to report endoscopy and EMR details prevents the inherent limitations of the retrospective nature of our study.

Our study did have limitations. First, it was a single-center study. Second, although we had a relatively large sample size, the small number of patients with local recurrence limited our ability to perform more sophisticated analysis to assess the effect of several factors on the local adenoma recurrence rate. Performance of follow-up endoscopic assessment by a single endoscopist could have led to inherent bias. To prevent this, the endoscopist performed extensive photographic documentation of the lesions and biopsy samples to evaluate the EMR sites.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we found that using a cap-fitted endoscope for systematic examination of the EMR site for any macroscopic polyp and performing APC at the resection edges led to a substantial decrease in the local recurrence rate in patients with large colon polyps after EMR.

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the support from the John Stroehlein endowment grant and Charles Butt and HEB grant.

Footnotes

Competing interests None

References

- 1.McNicol L, Story D A, Leslie K et al. Postoperative complications and mortality in older patients having non-cardiac surgery at three Melbourne teaching hospitals. Med J Aust. 2007;186:447–452. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb00994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Birkmeyer J D, Siewers A E, Finlayson E V et al. Hospital volume and surgical mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1128–1137. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa012337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moss A, Bourke M J, Williams S J et al. Endoscopic mucosal resection outcomes and prediction of submucosal cancer from advanced colonic mucosal neoplasia. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1909–1918. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.02.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rex D K. If endoscopic mucosal resection is so great for large benign colon polyps, why is so much surgery still being done? Endoscopy. 2018;50:657–659. doi: 10.1055/a-0589-0451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peery A F, Cools K S, Strassle P D et al. Increasing rates of surgery for patients with nonmalignant colorectal polyps in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:1352–1.36E6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bahin F F, Heitman S J, Rasouli K N et al. Wide-field endoscopic mucosal resection versus endoscopic submucosal dissection for laterally spreading colorectal lesions: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Gut. 2018;67:1965–1973. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-313823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahlenstiel G, Hourigan L F, Brown G et al. Actual endoscopic versus predicted surgical mortality for treatment of advanced mucosal neoplasia of the colon. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:668–676. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jayanna M, Burgess N G, Singh R et al. Cost analysis of endoscopic mucosal resection vs surgery for large laterally spreading colorectal lesions. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:271–278.e1-2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Law R, Das A, Gregory D et al. Endoscopic resection is cost-effective compared with laparoscopic resection in the management of complex colon polyps: an economic analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:1248–1257. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moss A, Williams S J, Hourigan L F et al. Long-term adenoma recurrence following wide-field endoscopic mucosal resection (WF-EMR) for advanced colonic mucosal neoplasia is infrequent: results and risk factors in 1000 cases from the Australian Colonic EMR (ACE) study. Gut. 2015;64:57–65. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Belderbos T D, Leenders M, Moons L M et al. Local recurrence after endoscopic mucosal resection of nonpedunculated colorectal lesions: systematic review and meta-analysis. Endoscopy. 2014;46:388–402. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1364970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knabe M, Pohl J, Gerges C et al. Standardized long-term follow-up after endoscopic resection of large, nonpedunculated colorectal lesions: a prospective two-center study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:183–189. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Facciorusso A, Di Maso M, Serviddio G et al. Factors associated with recurrence of advanced colorectal adenoma after endoscopic resection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:1148–1.154E7. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seo J Y, Chun J, Lee C et al. Novel risk stratification for recurrence after endoscopic resection of advanced colorectal adenoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:655–664. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.09.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Facciorusso A, Di Maso M, Serviddio G et al. Development and validation of a risk score for advanced colorectal adenoma recurrence after endoscopic resection. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:6049–6056. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i26.6049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raju G S, Lum P J, Ross W A et al. Outcome of EMR as an alternative to surgery in patients with complex colon polyps. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2016;84:315–325. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2016.01.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raju G S, Lum P J, Slack R S et al. Natural language processing as an alternative to manual reporting of colonoscopy quality metrics. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:512–519. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.01.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kandel P, Brand E C, Pelt J et al. Endoscopic scar assessment after colorectal endoscopic mucosal resection scars: when is biopsy necessary (ESCAPE trial) Gut. 2019;68:1633–1641. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-316574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brooker J C, Saunders B P, Shah S G et al. Treatment with argon plasma coagulation reduces recurrence after piecemeal resection of large sessile colonic polyps: a randomized trial and recommendations. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:371–375. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.121597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pohl H, Srivastava A, Bensen S P et al. Incomplete polyp resection during colonoscopy-results of the complete adenoma resection (CARE) study. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:74–800. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klein A, Tate D J, Jayasekeran V et al. Thermal ablation of mucosal defect margins reduces adenoma recurrence after colonic endoscopic mucosal resection. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:604–613. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim K Y, Jeon S W, Yang H M et al. Clinical outcomes of argon plasma coagulation therapy for early gastric neoplasms. Clin Endosc. 2015;48:147–151. doi: 10.5946/ce.2015.48.2.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Panos M Z, Koumi A. Argon plasma coagulation in the right and left colon: safety-risk profile of the 60W-1.2 l/min setting. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2014;49:632–641. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2014.903510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tate D J, Desomer L, Klein A et al. Adenoma recurrence after piecemeal colonic EMR is predictable: the Sydney EMR recurrence tool. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:647–6.56E8. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2016.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pommergaard H C, Burcharth J, Rosenberg J et al. Advanced age is a risk factor for proximal adenoma recurrence following colonoscopy and polypectomy. Br J Surg. 2016;103:e100–105. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Woodward T A, Heckman M G, Cleveland P et al. Predictors of complete endoscopic mucosal resection of flat and depressed gastrointestinal neoplasia of the colon. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:650–654. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buchner A M, Guarner-Argente C, Ginsberg G G. Outcomes of EMR of defiant colorectal lesions directed to an endoscopy referral center. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2012;76:255–263. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.02.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carvalho R, Areia M, Brito D et al. Endoscopic mucosal resection of large colorectal polyps: prospective evaluation of recurrence and complications. Acta Gastroenterol Belgica. 2013;76:225–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maguire L H, Shellito P C. Endoscopic piecemeal resection of large colorectal polyps with long-term followup. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:2641–2648. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3516-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sidhu M, Tate D J, Desomer L et al. The size, morphology, site, and access score predicts critical outcomes of endoscopic mucosal resection in the colon. Endoscopy. 2018;50:684–692. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-124081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhan T, Hielscher T, Hahn F et al. Risk factors for local recurrence of large, flat colorectal polyps after endoscopic mucosal resection. Digestion. 2016;93:311–317. doi: 10.1159/000446364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barosa R, Mohammed N, Rembacken B. Risk stratification of colorectal polyps for predicting residual or recurring adenoma using the Size/Morphology/Site/Access score. United Europ Gastroenterol J. 2018;6:630–638. doi: 10.1177/2050640617742485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]