Abstract

Fatty acid binding proteins play an important role in the transportation of fatty acids. Despite intensive studies, how fatty acids enter the protein cavity for binding is still controversial. Here, a gap-closed variant of human intestinal fatty acid binding protein was generated by mutagenesis, in which the gap is locked by a disulfide bridge. According to its structure determined here by NMR, this variant has no obvious openings as the ligand entrance and the gap cannot be widened by internal dynamics. Nevertheless, it still takes up fatty acids and other ligands. NMR relaxation dispersion, chemical exchange saturation transfer, and hydrogen-deuterium exchange experiments show that the variant exists in a major native state, two minor native-like states, and two locally unfolded states in aqueous solution. Local unfolding of either βB–βD or helix 2 can generate an opening large enough for ligands to enter the protein cavity, but only the fast local unfolding of helix 2 is relevant to the ligand entry process.

Significance

Fatty acid binding proteins transport fatty acids to specific organelles in the cell. To enable the transport, fatty acids must enter and leave the protein cavity. Despite many studies, how fatty acids enter the protein cavity remains controversial. Using mutagenesis and biophysical techniques, we have resolved the disagreement and further showed that local unfolding of the second helix can generate a transient opening to allow ligands to enter the protein cavity. Because lipid binding proteins are highly conserved in the three-dimensional structure and ligand binding, all of them may use the same local unfolding mechanism for ligand uptake and release.

Introduction

Fatty acid binding proteins (FABPs) are a family of specific carrier proteins that actively facilitate the transport of fatty acids to specific organelles in the cell for metabolism, storage, and signaling (1). They are critical meditators of metabolism and inflammatory processes and are considered promising therapeutic targets for metabolic diseases (2). Nine types of FABPs have been found in the cytosol of a variety of mammalian tissues (3). Different FABPs from humans share relatively low sequence identities, but they adopt similar three-dimensional (3D) structures with a slightly elliptical β barrel comprising two nearly orthogonal five-stranded β-sheets, a cap with two short α-helices, and a large cavity filled with water (Fig. 1 A; (2,3)). Nearly all structures obtained in both crystal and solution states show no obvious openings (4), but ligands can access the binding site located inside the cavity. Knowledge of how ligands enter the cavity is important for manipulating FABP’s function by blocking the ligand entrance. Previous molecular dynamics (MD) studies suggested three possible ligand entry sites for ligand and water to enter into or exit from the protein cavity: EI, located in the cap region involving the second α-helix (α2) and βC–βD and βE−βF turns; EII, the gap between βD and βE; and EIII, in the area around the N-terminus (5, 6, 7, 8). Very recently, our studies on human intestinal FABP (hIFABP) have showed that opening the cap by swinging the two helices away from the barrel is dispensable for ligands to enter the cavity and further demonstrated the existence of a minor conformational state that undergoes transient local unfolding in α2 on a submillisecond timescale and thus provides a temporary opening in the EI region for ligand entry (9). Our recent simulation work has also revealed that the α2 tends to unfold more easily than other segments of the protein (10). Nevertheless, we could not exclude the presence of EII and EIII.

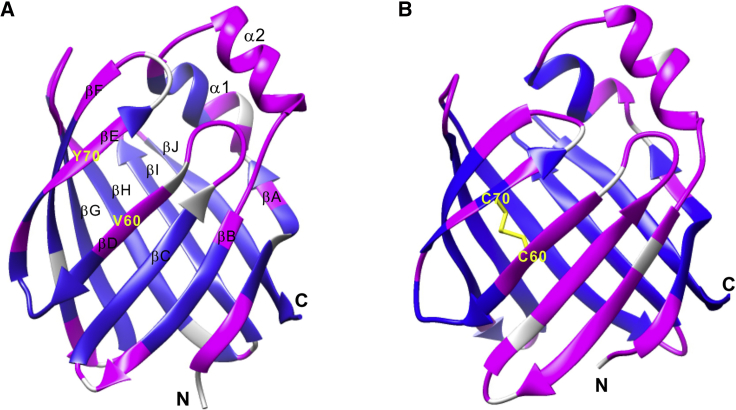

Figure 1.

Structures of WT hIFABP (A) and its V60C/Y70C variant (B). Residues with HDX rates smaller than 0.01 s−1 are indicated in blue, otherwise in pink. The residues with unavailable data are in gray. The disulfide linkage is shown in yellow sticks. To see this figure in color, go online.

There is a gap in the β-sheet of the barrel structure, in which no main-chain hydrogen bonds exist between βD and βE (Fig. 1 A; (11)). This is common to intracellular lipid binding proteins including FABPs, suggesting that the gap may play a role in lipid uptake and release (11). Recent MD simulations on human heart FABP show that the gap between βD and βE can open to become significantly wider (5,8). In addition, MD simulations on a human myelin protein P2, which is a member of the FABP superfamily, indicate that a large-scale opening of the barrel between βD and βE can occur through moving the C-terminal region of βE and the N-terminal region of βF outwardly away from βD and βG (7). Upon this opening, the internalized cavity becomes accessible by ligands. Although computational studies suggest that the opening of the barrel is likely a general mechanism for ligand entry into FABPs, experimental evidence is still lacking.

To investigate if ligands indeed enter the cavity through EII via widening the gap, here, we generated a gap-closed variant of hIFABP by introducing a disulfide linkage between βD and βE. Structure characterization reveals that the variant adopts a structure without obvious openings, and its gap cannot be widened substantially through internal dynamics. Similar to the wild-type (WT) hIFABP, the variant still takes up fatty acids and other ligands. Dynamics characterization shows that the variant exists in multiple conformational states in aqueous solution and the local unfolding process from the major native “closed” state to a minor “open” state with a locally unfolded helix 2 is relevant to ligand uptake and release.

Materials and Methods

Protein sample preparation and NMR spectroscopy

The construct of hIFABP mutant V60C/Y70C was generated using a two-step polymerase chain reaction (PCR) scheme. The mutant (variant) was expressed in Escherichia coli, purified, and delipidated using the protocol described previously (12). For structure determination, a 13C,15N-labeled sample was used to acquire NMR triple-resonance data including HNCA, HN(CO)CA, MQ-HCCH-TOCSY, and 13C,15N-edited NOESY (13,14). Using 15N-labeled samples, Car-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill (CPMG) and chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) experiments were conducted at 30°C, and amide hydrogen-deuterium exchange (HDX) experiments were conducted at 25°C. Unlabeled protein samples were used for stopped-flow and affinity measurement experiments at 20°C. All NMR experiments were performed on samples containing ∼1 mM protein, 20 mM sodium phosphate, and 50 mM NaCl on a Bruker 800 MHz instrument equipped with a cryoprobe. Except the samples used for HDX at pH 7.2 and for stopped-flow at pH 9.4, other samples were at pH 7.0.

The NMR data were processed using NMRPipe (15) and analyzed for resonance assignment using Sparky (16). NMR resonance assignment and structure determination of the V60C/Y70C variant was achieved using a NOESY-based strategy described previously (17). On the basis of distance constraints derived from unambiguous NOE assignments and dihedral angle constraints derived from chemical shifts, the structure was calculated with Xplor-NIH (18) using the standard simulated annealing method.

HDX rates were determined from NMR signal intensity changes with HDX time after dissolving lyophilized protein into heavy water solution. Each 1H-15N HSQC was acquired with an interscan delay of 0.3 s and four scans (total experimental time of 149 s) using the so-fast HSQC scheme. Amide hydrogen exchange rates were measured in water solution using the radiation damping-based water inversion method (19).

15N relaxation dispersion (RD) data were acquired with a continuous wave decoupling and phase-cycled CPMG method (20,21) using a constant time relaxation delay of 30 ms and interscan delay of 2 s. RD data at 16 different CPMG fields from 33.3 to 1000 Hz were collected by varying the separation of CMPG pulses. To estimate uncertainties in the apparent relaxation rates, the measurements at a CPMG field of 66.6 Hz were repeated three times.

CEST profiles were obtained at two different weak saturation fields (13.6 and 27.2 Hz) with a saturation time of 0.5 s and interscan delay of 1.5 s (22,23). For each saturation field, 51 HSQC-based spectra were acquired using a series of 15N carrier frequencies ranging from 106 to 131 ppm at a spacing of 0.5 ppm. The uncertainties of the data points were estimated from the SD of the points over a region far away from CEST dips.

RD and CEST data analysis

To extract conformational exchange parameters, RD and CEST data of the residues displaying three obvious CEST dips were simultaneously fitted to the following four-state exchange model (Fig. 2) as described previously (24). Briefly, the data for each residue were fitted to estimate individual exchange rates (kex1, kex2, and kex3), populations (pI1, pI2, and pI3), chemical shifts (δI1, δI2, and δI3), intrinsic transverse relaxation rate (R2), and longitudinal relaxation rate (R1). From these estimations, initial values of the fitting parameters were determined roughly. Next, the data for all the residues were fitted globally to extract global kinetics parameters (exchange rates and populations) and residue-specific parameters (chemical shifts and relaxation rates). In the fitting, the R2 and R1 values for each residue were assumed to be independent of conformational states. Error estimation also followed the previous method (24).

Figure 2.

Four-state exchange model. kex1 (kex2, kex3) is the total exchange rate between state N and state I1 (I2, I3).

For the residues showing a significant conformational exchange contribution to transverse relaxation (Rex) and exhibiting one or two CEST dips, their chemical shifts in the minor states were determined by fitting the RD and CEST data of each residue to the four-state model by fixing the exchange rates and populations of minor states at the values derived from the global fitting.

Stopped flow

All the stopped-flow experiments were conducted on an Applied Photophysics spectrometer by mixing protein (4 μM protein and 50 mM NaCl (pH 9.4)) and oleic acid (50 mM NaCl (pH 9.4)) solutions in equal volumes. At each oleic concentration, the experiment was repeated 10 times, and the average data were used for analysis. To extract apparent binding rates, each stopped-flow trace was fitted to the following mono- and biexponential functions:

| (1) |

| (2) |

where Fint(t) is the fluorescence intensity of tryptophan residues observed at time t, Fint1 and Fint2 are the fluorescence intensities associated with the first and second binding processes, respectively, k1 and k2 are the apparent association rates of the first and second binding processes, respectively, and Fintmax is the fluorescence intensity in the equilibrium state.

ANS titration

The binding affinity of 1-anilinonaphthalene-8-sulfonic acid (ANS) to the gap-closed variant was measured using a Shimadzu RF-5301 fluorescence spectrometer. The change of ANS fluorescence intensity with protein concentration (F(x)) was fitted to a one-site binding model, as follows:

| (3) |

where L0 is the total ANS concentration (1 μM), x is the total protein concentration, Kd is the dissociation constant, and ΔA is the difference of fluorescence intensities between the protein-free and protein-bound ANS.

Results and Discussion

Structure of gap-closed hIFABP variant

A hIFABP mutant was generated by introducing a disulfide linkage between βD and βE, which was achieved by mutating V60 located in βD and Y70 in βE into cysteine (Fig. 1). The mutant displays substantially different 1H-15N NMR correlation spectra in the absence and presence of reducing agent dithiothreitol (Fig. S1), indicating that a disulfide bond exists in the mutant in the absence of reducing agents. The 13Cβ chemical shifts of C60 (44.1 ppm) and C70 (45.3 ppm), which are typical for oxidized cysteine, further demonstrate the formation of a disulfide bond. To examine if the introduction of the disulfide bond induces structural changes, the structure of the mutant was solved based on distance and dihedral angle restraints obtained from triple-resonance NMR experiments (Table S1). The structure and NMR resonance assignments were deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB: 6L7K) and the Biological Magnetic Resonance Data Bank (BMRB: 36291), respectively. The mutant is very similar to the WT protein in overall structure (Fig. 1; Fig. S2) and has no obvious openings on the protein surface (Fig. S3). Introduction of the disulfide bond reduces the gap between βD and βE by ∼1 Å. Nevertheless, there are still no main-chain hydrogen bonds between βD and βE. In addition, the upper part of βB–βD of the variant orientates slightly more outward than that of the WT hIFABP (Fig. S2). Because the middle of βD is connected with the middle of βE by a covalent linkage, widening of the gap between these two strands should be insignificant (<1 Å) by internal dynamics, if such an opening can happen. Thus, the V60C/Y70C hIFABP mutant is also referred to as gap-closed hIFABP variant.

Binding of ligands to gap-closed hIFABP variant

Apart from fatty acids, FABPs also bind other lipophilic molecules such as 1-anilinonaphthalene-8-sulfonic acid (ANS) that is an excellent fluorescent probe. Previous studies have shown that ANS resides in the fatty acid binding site and binds IFABP in a 1:1 ratio, the same as fatty acids (12,25,26). In this study, ANS was used as a fatty acid analog to test ligand binding to the gap-closed variant. On the basis of fluorescence titration, the gap-closed variant still binds ANS (Fig. S4), even though βD and βE are covalently linked, and the gap cannot be widened more than 1 Å through internal dynamics. The variant with a disulfide bond has an ANS binding affinity of 10.2 ± 0.3 μM, which is similar to that for its reduced form without a disulfide linkage (11.2 ± 0.4 μM) and larger than that for the WT protein (7.1 ± 0.2 μM), suggesting that the side chains of V60 or/and Y70 are likely involved in interactions with ANS. The results show that opening the β barrel between βD and βE is unnecessary for ligands to enter the protein cavity for binding and imply that opening another region should occur through protein structural changes.

Coexistence of multiple conformational states of gap-closed hIFABP

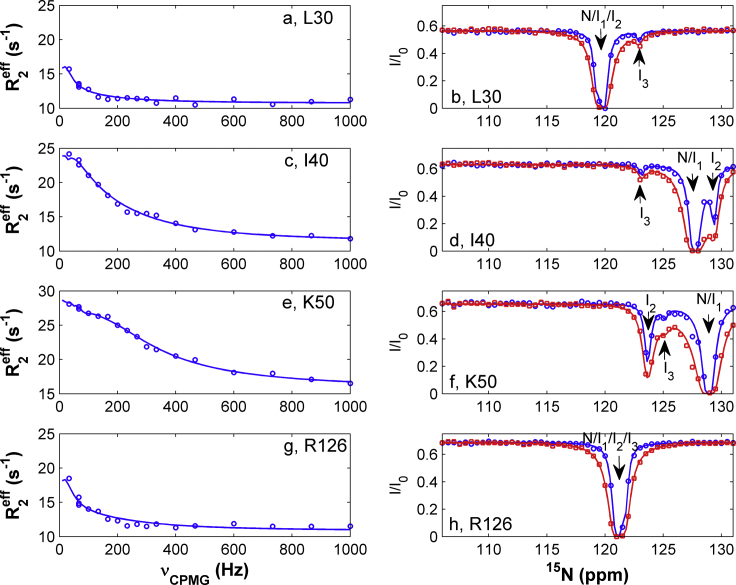

Similar to WT hIFABP, the gap-closed variant has no obvious openings (Fig. S3). To reveal how ligands enter the cavity, we probed conformational exchanges of the variant using NMR RD and CEST experiments. 75 out of 131 residues displayed RD with Rex values larger than 3 s−1 on an 800 MHz spectrometer (Fig. 3, a, c, e, and g), six residues had Rex values between 2 and 3 s−1, 31 residues had Rex values smaller than 2 s−1, and 18 residues with peak overlapping or weak signals were excluded for analysis. Here, Rex is defined as R2eff(1000) – R2eff(33), where R2eff(1000) and R2eff(33) are the relaxation rates measured at CPMG fields of 1000 and 33.3 Hz, respectively. The RD data indicate that at least one “invisible” state (I1) is in dynamic equilibrium with the observed native state (N) on a millisecond timescale. Among the 75 residues with Rex > 3 s−1, 18 residues each exhibited three obvious dips (Fig. 3 d) that correspond to one native state and two minor states, 27 residues each displayed two obvious dips (Fig. 3, b and f), and 30 residues had only one dip (Fig. 3 h) in their CEST profiles. The CEST data suggest the presence of at least two additional “invisible” minor states (I2 and I3) that undergo conformational exchanges with state N on a subsecond timescale. To obtain structural information of the “invisible” states and kinetics parameters for conformational exchange processes, a four-state model (Fig. 2) was used to fit both the CEST and RD data simultaneously.

Figure 3.

Representative RD (a, c, e, and g) and CEST (b, d, f, and h) profiles. The experimental CEST data at radio frequency fields of 13.6 and 27.2 Hz are indicated by “o” and “□” respectively. The solid lines are best fits obtained with a four-state model. The locations (or chemical shifts) of states N, I1, I2, and I3 in the CEST profiles are indicated by arrows. To see this figure in color, go online.

Fitting the data from all the residues with three obvious dips globally, we obtained populations of states I1, I2, and I3 (pI1 = 3.4 ± 0.3%, pI2 = 5.3 ± 0.2%, and pI3 = 1.8 ± 0.9%) and their respective exchange rates with state N (kex1 = 1629 ± 116 s−1, kex2 = 82 ± 5 s−1, and kex3 = 16 ± 8 s−1). 15N chemical shifts of the minor states determined from the data fitting are listed in Table S2. Although only one set of RD data recorded on a single static magnetic field was used to determine the parameters associated with the intermediate exchange process (kex1, pI1, and δI1), the parameters obtained by fitting globally the data from 18 residues had relatively small uncertainties. Using simulated data, we have recently also demonstrated that reliable kinetics parameters and chemical shifts can be obtained by fitting RD data on a single magnetic field from multiple residues (>10) to a global exchange model (9). For other residues with 1–2 CEST dips as well as Rex > 2 s−1, their chemical shifts in minor states were obtained from data analysis by fixing kex1, pI1, kex2, pI2, kex3, and pI3 at the values derived from the global fitting, which are also listed in Table S2.

Folded and unfolded proteins have very distinct 15N chemical shifts. Comparing chemical shifts of the minor and native states (Table S2), we can see that states I1 and I2 are much more similar to state N than unfolded state U (Fig. 4, A–D), but state I3 is significantly different from both states N and U (Fig. 4, E and F). The chemical shift differences between states I3 and N were also mapped onto the 3D structure to visualize the location of the residues with significant shift differences (Fig. S5). For state I3, residues located in the N-terminal region of βA (F2–W6), βB–βD (N35–L64) and C-terminal end of α2 (L30–D34) are similar to the unfolded state; C70–N71 in the C-terminal region of βE and T116 in βI are different from both the unfolded and native states, and residues located in other regions are similar to the native state in terms of 15N chemical shift (Fig. 4, E and F). For instance, the chemical shifts of residues K37–E43 in state I3 each differ from those in state N by more than 3.4 ppm but deviate from those in state U by less than ∼1.0 ppm (Fig. 4, E and F; Table S2). Therefore, states I1 and I2 are native like, whereas state I3 is partially unfolded, in which the N-terminal region of βA, βB–βD, and the C-terminal end of α2 are mainly disordered. The unfolding rate from state N to state I3 is ∼0.3 s−1 (pI3∗kex3), significantly smaller than the conversion rates from state N to I1 (∼55 s−1) and I2 (4 s−1).

Figure 4.

Differences of 15N chemical shifts between states I1 and N (A), between state I1 and unfolded state (U) (B), between states I2 and N (C), between states I2 and U (D), between states I3 and N (E), and between states I3 and U (F). In (E) and (F), the residues in the N-terminal region of βA, C-terminal region of α2, and βB–βD are marked in red. Secondary structure elements are shown on the tops of (A) and (B). To see this figure in color, go online.

To examine if there are other conformational exchanges in the gap-closed variant, amide hydrogen exchange experiments were performed. 62 out of 131 residues displayed 1H-15N correlations in the first HDX spectrum, which was recorded with a total acquisition time of 149 s and a dead time of ∼160 s. Their HDX rates are listed in Table S3. For other residues with HDX rates larger than 0.2 s−1, the exchange rates of their backbone amides with water hydrogen were measured (Table S3). As expected, the residues not involved in H-bonding have large amide hydrogen exchange rates and small protection factors (PFs). Interestingly, all residues located in α2, βB, and βC of the gap-closed variant have small PFs (<100) (Fig. 1; Table S3), even though their backbone amides are involved in H-bonding in state N. In contrast, most residues located in βB and βC of the WT hIFABP and its cap-closed variant have very large PFs (>1000) (Fig. 1; (9,24)). The exchange rates for most residues at pH 7.2 were 1.4–2.0 times as large as those measured at pH 7.0 (Table S3), indicating that the amide hydrogen exchange can be described by the EX2 model (27). Using this model, the population of an amide in a disordered form can be approximated as 1/PF. According to the PFs of the amides involved in H-bonding (Table S3), the populations of the disordered form were ∼15–30% for α2, ∼2% for N-terminal region of βA, ∼0.5–8% for βB and βC, and <0.1% for α1 and βF–βJ. It is noteworthy that the populations estimated from the PFs are error prone, strongly depending on the predicted exchange rates. This result further supports that states I1 (pI1 = 3.4%) and I2 (pI2 = 5.3%) are native like rather than unfolded, whereas state I3 (pI3 = 1.8%) is partially unfolded, in which βB, βC, and α2 are mainly disordered.

The population of the disordered form for α2 estimated from PFs (∼15–30%) is much larger than the population of state I3 derived from our CEST data (1.8%), suggesting the presence of an additional state in which only α2 is disordered. This locally unfolded state is denoted as I4. Because state I4 was not observed by CEST and RD experiments, its exchange rate with state N should be significantly smaller than kex3 (16 s−1) or much larger than kex1 (1600 s−1). In the former case (slow exchange regime), the residues in α2 should give rise to two sets of 1H-15N correlation peaks corresponding to states N and locally unfolded I4. In fact, only one set of peaks corresponding to state N were observed, indicating that state I4 must undergo a fast exchange with state N. This fast exchange should be on the microsecond timescale so that the exchange could not be detected by 15N CPMG experiments.

Functionally relevant conformational exchange

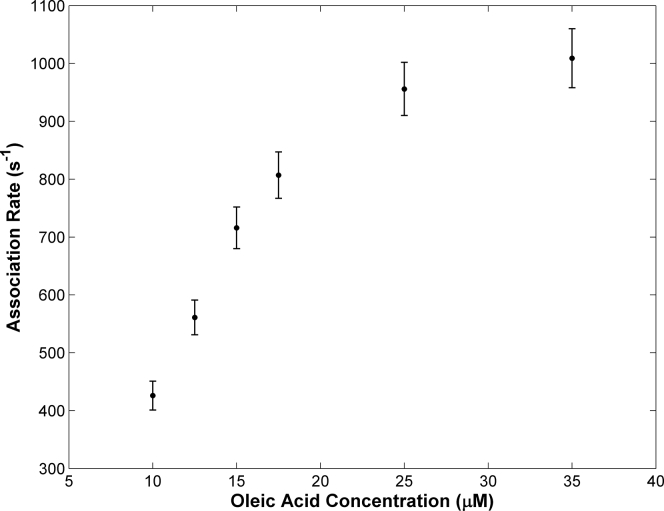

The partially unfolded state I3 should have an opening large enough for ligands to enter the protein cavity. To examine if this partial unfolding process is relevant to the uptake of fatty acids, we measured the apparent association rate of oleic acid binding to the gap-closed hIFABP using fluorescence stopped flow. The stopped-flow profiles could be fitted well to a biexponential function instead of monoexponential function when oleic acid concentrations were lower than 25 μM (Fig. S6). The F-statistics derived from the bi- and mono-exponential models were much larger than the critical value (7.0) at a confidence level of 99.9% (Table S4), rejecting the monoexponential model. This suggests that the ligand binds the protein in at least two steps. At higher oleic acid concentrations, the intrinsic protein fluorescence signal started to decay after a mixing time of ∼4 ms (Fig. S6) because of the quenching effect, which was not observed for the WT protein (9). In this case, only the apparent association rate for the fast step could be estimated. The fast apparent rates increased with oleic acid concentrations initially and then gradually reached a plateau with a further increase of ligand concentration (Fig. 5). This result suggests that there is a rate-limiting step before the ligand association step, and the rate limit is ∼1000 s−1 for the gap-closed variant. On the other hand, the rates for the second association step were small (∼20 s−1) and nearly independent of ligand concentrations (Table S4).

Figure 5.

Dependences of apparent association rates for the fast step on ligand concentrations. The experimental data are shown in filled dots. The vertical bars indicate the errors of the association rates.

The binding kinetics results for the gap-closed mutant are similar to those for the cap-closed mutant and WT protein (9). Therefore, the three-step binding model for the cap-closed variant described previously should be applicable to this gap-closed variant too. In this model, the maximal apparent association rate for the fast step should be smaller than the conversion rate from a closed state to an open state because the protein stays mainly in a closed state. If fact, the maximal apparent association rate (∼1000 s−1) is much larger than the conversion rates from state N to I1, I2, and I3 (<55 s−1). So the local unfolding process from state N to I3 and the other two conformational exchange processes revealed by RD and CEST are irrelevant to the ligand entry for the gap-closed variant. The results also suggest that states I1, I2, and I3 are not involved in the ligand binding process. Although these three minor states are unnecessary for the binding of small molecules to IFABP, they may play a role in interactions with IFABP binding proteins. Different from state I3, state I4 with a disordered α2 is in fast exchange with state N, which is similar to the locally unfolded state of the cap-closed variant. In common with WT hIFABP and its cap-closed variants, the gap-closed variant has PF values smaller than 100 for R28-A32 in α2 but larger than 1000 for V17-M21 in α1 (9,24), even though the amides of these residues are all involved in H-bonding and have similar water accessibility in state N, suggesting the presence of a common minor state with locally unfolded α2 for all hIFABP proteins. Our recent study (9) on the cap-closed mutant showed that local unfolding of α2 is the rate-limiting step for ligands to enter the hIFABP cavity for binding. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that the unfolding of α2 also controls the entry of ligands into the gap-closed variant, and the conversion rate from state N to I4 is similar to the maximal ligand association rate (∼1000 s−1). State I4 not only contains an opening through which ligands can enter the cavity of IFABP for binding but also undergoes conformational exchange with state N rapidly. This means that state I4 is an indispensable intermediate state for ligands to bind IFABP. Currently, FABP inhibitors are designed based on the ligand binding site inside the protein cavity (28). Our study suggests an alternative type of inhibitors that can stabilize α2 and suppress state I4, in turn preventing fatty acids from entering the FABP cavity for binding.

Conclusions

In summary, we have generated a gap-closed hIFABP variant with a disulfide linkage between strands βD and βE, which has a similar 3D structure to the WT protein and has no obvious opening on its surface. The variant always stays in a gap-closed state because of the presence of the disulfide linkage, but it still takes up fatty acids and other lipophilic ligands. Thus, ligands do not enter the protein cavity for binding via opening the gap, rejecting the previously proposed gap-opening mechanism. The native state of the gap-closed variant (N) is in dynamic equilibrium with two minor native-like states (I1 and I2), one locally unfolded state in which the N-terminal region of βA, βB–βD, and α2 are mainly disordered (I3) and one locally unfolded state in which α2 is mainly disordered (I4). The conversion rate from state N to I3 (0.3 s−1) is much smaller than the apparent association rate of oleic acid, indicating that ligands do not enter the protein cavity through the opening created by local unfolding of the βB–βD region. Local unfolding of α2 is fast and thus relevant to the ligand entry process.

Author Contributions

D.Y. designed the research. T.X. and Y.L. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. J.S.F. analyzed the NOESY data and calculated the structure. Y.L. and D.Y. wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Singapore Ministry of Education, Academic Research Fund Tier 2 (MOE2017-T2-1-125).

Editor: Elizabeth Komives.

Footnotes

Supporting Material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2019.12.005.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Zimmerman A.W., Veerkamp J.H. New insights into the structure and function of fatty acid-binding proteins. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2002;59:1096–1116. doi: 10.1007/s00018-002-8490-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hotamisligil G.S., Bernlohr D.A. Metabolic functions of FABPs--mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2015;11:592–605. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2015.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hertzel A.V., Bernlohr D.A. The mammalian fatty acid-binding protein multigene family: molecular and genetic insights into function. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2000;11:175–180. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(00)00257-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sacchettini J.C., Gordon J.I., Banaszak L.J. Crystal structure of rat intestinal fatty-acid-binding protein. Refinement and analysis of the Escherichia coli-derived protein with bound palmitate. J. Mol. Biol. 1989;208:327–339. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90392-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matsuoka D., Sugiyama S., Matsuoka S. Molecular dynamics simulations of heart-type fatty acid binding protein in apo and holo forms, and hydration structure analyses in the binding cavity. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2015;119:114–127. doi: 10.1021/jp510384f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Long D., Mu Y., Yang D. Molecular dynamics simulation of ligand dissociation from liver fatty acid binding protein. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6081. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laulumaa S., Nieminen T., Kursula P. Structure and dynamics of a human myelin protein P2 portal region mutant indicate opening of the β barrel in fatty acid binding proteins. BMC Struct. Biol. 2018;18:8. doi: 10.1186/s12900-018-0087-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo Y., Duan M., Yang M. The observation of ligand-binding-relevant open states of fatty acid binding protein by molecular dynamics simulations and a Markov state model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:E3476. doi: 10.3390/ijms20143476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xiao T., Fan J.S., Yang D. Local unfolding of fatty acid binding protein to allow ligand entry for binding. Angew. Chem. Int.Engl. 2016;55:6869–6872. doi: 10.1002/anie.201601326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng P., Liu D., Long D. Atomistic insights into the functional instability of the second helix of fatty acid binding protein. Biophys. J. 2019;117:239–246. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2019.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sacchettini J.C., Gordon J.I., Banaszak L.J. The structure of crystalline Escherichia coli-derived rat intestinal fatty acid-binding protein at 2.5-A resolution. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:5815–5819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Long D., Yang D. Millisecond timescale dynamics of human liver fatty acid binding protein: testing of its relevance to the ligand entry process. Biophys. J. 2010;98:3054–3061. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.03.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang D., Zheng Y., Wyss D.F. Sequence-specific assignments of methyl groups in high-molecular weight proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:3710–3711. doi: 10.1021/ja039102q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu Y., Long D., Yang D. Rapid data collection for protein structure determination by NMR spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:7722–7723. doi: 10.1021/ja071442e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Delaglio F., Grzesiek S., Bax A. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee W., Tonelli M., Markley J.L. NMRFAM-SPARKY: enhanced software for biomolecular NMR spectroscopy. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:1325–1327. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu Y., Zheng Y., Yang D. A new strategy for structure determination of large proteins in solution without deuteration. Nat. Methods. 2006;3:931–937. doi: 10.1038/nmeth938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schwieters C.D., Kuszewski J.J., Clore G.M. Using Xplor-NIH for NMR molecular structure determination. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2006;48:47–62. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fan J.S., Lim J., Yang D. Measurement of amide hydrogen exchange rates with the use of radiation damping. J. Biomol. NMR. 2011;51:151–162. doi: 10.1007/s10858-011-9549-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang B., Yu B., Yang D. A (15)N CPMG relaxation dispersion experiment more resistant to resonance offset and pulse imperfection. J. Magn. Reson. 2015;257:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Long D., Liu M., Yang D. Accurately probing slow motions on millisecond timescales with a robust NMR relaxation experiment. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:2432–2433. doi: 10.1021/ja710477h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vallurupalli P., Bouvignies G., Kay L.E. Studying “invisible” excited protein states in slow exchange with a major state conformation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:8148–8161. doi: 10.1021/ja3001419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lim J., Xiao T., Yang D. An off-pathway folding intermediate of an acyl carrier protein domain coexists with the folded and unfolded states under native conditions. Angew. Chem. Int.Engl. 2014;53:2358–2361. doi: 10.1002/anie.201308512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu B., Yang D. Coexistence of multiple minor states of fatty acid binding protein and their functional relevance. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:34171. doi: 10.1038/srep34171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kirk W.R., Kurian E., Prendergast F.G. Characterization of the sources of protein-ligand affinity: 1-sulfonato-8-(1′)anilinonaphthalene binding to intestinal fatty acid binding protein. Biophys. J. 1996;70:69–83. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79592-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Velkov T., Chuang S., Scanlon M.J. The interaction of lipophilic drugs with intestinal fatty acid-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:17769–17776. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410193200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krishna M.M., Hoang L., Englander S.W. Hydrogen exchange methods to study protein folding. Methods. 2004;34:51–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Furuhashi M., Tuncman G., Hotamisligil G.S. Treatment of diabetes and atherosclerosis by inhibiting fatty-acid-binding protein aP2. Nature. 2007;447:959–965. doi: 10.1038/nature05844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.