Abstract

Selective biofilters are used by cells to control the transport of proteins, nucleic acids, and other macromolecules. Biological filters demonstrate both high specificity and rapid motion or high flux of proteins. In contrast, high flux comes at the expense of selectivity in many synthetic filters. Binding can lead to selective transport in systems in which the bound particle can diffuse, but the mechanisms that lead to bound diffusion remain unclear. Previous theory has proposed a molecular mechanism of bound-state mobility based only on transient binding to flexible polymers. However, this mechanism has not been directly tested in experiments. We demonstrate that bound mobility via tethered diffusion can be engineered into a synthetic gel using protein fragments derived from the nuclear pore complex. The resulting bound-state diffusion is quantitatively consistent with theory. Our results suggest that synthetic biological filters can be designed to take advantage of tethered diffusion to give rapid, selective transport.

Significance

Biological filters control the passage of proteins and other macromolecules between compartments of living systems. Determination of molecular mechanisms giving selective transport would enable the design of both selective filters and particles designed to penetrate biological barriers for drug delivery. One such mechanism arises from transient binding to dynamic polymer tethers. We designed a biomaterial that supports this type of tethered diffusion, demonstrating the potential to engineer bioinspired filters.

Introduction

Living systems depend on molecular filters to selectively control transport of macromolecules. Binding interactions affect selective filtering in a wide range of biological systems, but the molecular mechanisms by which binding leads to selectivity are often unclear. In some cases, particles that bind to a selective barrier are hindered, whereas inert particles pass more readily. For example, nanoparticles designed for drug delivery through mucosal membranes are most effective when their binding interactions to mucus are minimized (1, 2, 3). In other cases, biofilters use binding to enhance the flux of transported proteins, as in the case of the nuclear pore complex (NPC). Proteins that bind to the barrier have a higher flux through it than do inert proteins (4, 5, 6). This suggests that the function of binding in selective biological filters is complex and context dependent, motivating further study.

The NPC is a filter that relies on binding to control protein flux. The selective barrier of the NPC controls transport between the cytoplasm and nucleus. It consists of a channel ∼50 nm in diameter and 100 nm long that is filled with intrinsically disordered FG nucleoporins (FG Nups), named for their many short hydrophobic phenylalanine-glycine (FG) motifs in an otherwise hydrophilic protein (Fig. 1 A; (7,8)). Transport factors are proteins that bind to the FG motifs and pass rapidly through the NPC, carrying cargo with them. In contrast, nonbinding proteins larger than ∼30 kDa have much lower flux through the pore than similarly sized transport factor-cargo complexes (4, 5, 6). Although models of diffusion within the NPC have been developed to explain selectivity, many reduce the problem to that of a particle diffusing within an effective energy landscape (6,9, 10, 11, 12), an approach that does not address the molecular mechanisms of diffusion that could lead to selectivity. Therefore, we sought to investigate mechanisms of binding and mobility that can lead to selective transport.

Figure 1.

(A) Schematic of NPC and FG constructs. The NPC (gray) is filled with FG Nups (blue polymers) that selectively passage transport factors (green) that bind to FG Nups while blocking nonbinding proteins (red). FSFG6 and FSFG12 are peptides derived from the FG Nup Nsp1 containing 6 or 12 FSFG motifs. (B) A schematic showing that transport factors bound to an FG Nup fragment can retain mobility (top) and the energy landscape used to model a protein undergoing free diffusion (flat line) or bound diffusion (harmonic well) when bound to a flexible tether (bottom) is given. (C) A schematic of gel fabrication is shown. A precursor solution is polymerized upon exposure to ultraviolet illumination, tethering FG peptides to the resulting gel. (D) An experimental image of a gel equilibrated in a reservoir containing a fluorescent transport factor and inert protein is shown, scale bar is 300 μm. To see this figure in color, go online.

Recent work has highlighted the importance of bound mobility in selective transport (13, 14, 15). A particle’s steady-state flux through a filter can be increased by binding only if the bound particle remains mobile (16, 17, 18). Flux through a material depends on the number of particles in the material, their concentration gradient, and their movement. When particles cannot move when bound, the increase in particle number, and therefore concentration gradient, is exactly cancelled by the slowing of the particles during the time they spend bound (13,16,19). On the other hand, if particles can move when bound, their increase in concentration due to binding does increase particle flux. An increase in particle flux due to binding occurs even when the bound particle moves more slowly than the freely diffusing one. Bound mobility is thus necessary for binding-mediated selective transport. The degree of selective transport depends not only on the bound mobility but also on material parameters. For example, slower free diffusion and higher binding site concentrations both lead to more selective filters.

An open question is what molecular mechanisms lead to bound mobility. Previous work made the intuitive proposal that a filter can sustain bound mobility if all of the components, including the binding motifs, are mobile (16). However, in a filter, the attachment site for a binding motif typically is stationary. In this case, several potential mechanisms can contribute to motion of a particle while bound. For example, if binding motifs are tightly spaced, then particles with multiple binding sites can move between binding motifs without unbinding (14,15). Another possible molecular mechanism for bound diffusion is diffusion during short-lived binding interactions with flexible polymers (13). Dynamic polymers allow a bound particle to move and may additionally drive motion because of elastic kicks when extended tethers bind (Fig. 1 B; (13,20,21)). In short, an extended FG Nup is expected to restrain a bound transport factor. This restraint can be approximated as motion within a harmonic potential because the polymer dynamics are on the nanosecond timescale (14), much faster than the timescale for the transport factor to diffuse the mean end-to-end distance of the polymer. The resulting motion during each binding event is sufficient for bound mobility leading to selective transport (13). Moreover, the small forces exerted if the binding occurs away from the center of the well may exert a sufficiently large force to drive bound motion (20,21). When applied to transport factors binding to disordered FG Nups within the NPC, a theory based on tethered diffusion agrees with experimental measurements of selective transport of NTF2 (4,13,22,23), suggesting that this mechanism may contribute to selective transport through the NPC.

Materials and Methods

Protein expression, purification, and labeling

We aimed to use proteins with rapid dynamics, including diffusion-limited on rates, and well-established binding affinities. For this reason, we chose yeast nuclear transport factor 2 (NTF2) and synthetic fragments derived from the yeast FG Nup Nsp1 (FSFG6 and FSFG12 (24,25)). NTF2 is of similar size to the red fluorescent protein mCherry, which is inert to the FG-Nup-based protein fragments. NTF2, FSFG6, FSFG12, and mCherry (a gift from Amy Palmer) were expressed in BL21 DE3 Gold cells. All proteins contained a C-terminal His tag. FG constructs also contained a terminal cysteine. Cultures were grown in LB to OD 0.6–0.8 and then induced for 2–4 h with 1 mM IPTG (NTF2 and FG constructs) or 100 mM IPTG overnight (mCherry). The periplasmic matrix was removed by resuspending cell pellets in SHE buffer (20% sucrose, 50 mM HEPES, 1 mM EDTA), spinning down and resuspending in 5 mM MgSO4, incubating 10 min on ice, and spinning down and discarding supernatant (26). Proteins were purified with a cobalt affinity column in potassium transport buffer (PTB; 150 mM KCl, 20 mM HEPES, 2 mM MgCl2).

To conjugate the FG constructs to the gel scaffold, we attached a reactive bisacrylamide moiety to the thiol of the FG constructs. The protein was reduced using immobilized TCEP reducing gel (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) in a spin column and spun into a solution of 300 mM triethanolamine and 10-fold molar excess bisacrylamide. Reaction mixture was incubated shaking at room temperature for 30 min, dialyzed into 25 mM NH4HCO3, and lyophilized. The labeling efficiency was quantified with an Ellman’s reagent assay.

For visualization, NTF2 was labeled with fluorescein-NHS. NTF2 in PTB was added to 15-fold molar excess fluorescein-NHS and incubated stirring at room temperature for 1 h. Reaction mixture was repurified using a cobalt affinity column, washing with at least 100 column volumes of PTB before elution to remove unreacted dye. Labeled NTF2 was eluted with 300 mM imidazole in PTB, dialyzed into PTB to remove imidazole, and frozen within 24 h of labeling to minimize dye hydrolysis. Labeled NTF2 was thawed immediately before use.

Gel fabrication

Polyacrylamide gels were chosen as the substrate because of the ease of tuning their properties and their biocompatibility (27, 28, 29, 30). Gel precursor solutions were prepared with 6% v/v acrylamide and 0.2% v/v bisacrylamide (30% acrylamide/bisacrylamide stock 29:1, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), 2 mM LAP photoinitiator (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) (31), and 0.67 mM resuspended FSFG-bis in PTB (10 mg/mL FSFG6 or 20 mg/mL FSFG12). Precursor solutions were protected from light and degassed for 10 min immediately before polymerization.

We designed a flow chamber using a PDMS mold to allow for facile gel fabrication and exchange of the surrounding solution. The chambers were ∼400 μm deep, chosen so that the majority of a 0.5 or 1.0 μL polymerized droplet would fit within the field of view of a 4× objective. Unpolymerized precursor solution was placed on a coverslip. The chamber was closed, and the gel was polymerized by a 30-s exposure to 365-nm light at ∼220 mW/cm2. To remove any unconjugated precursor, gels were then rinsed with 100 gel volumes of PTB and soaked in PTB overnight at 4°C inside the sealed flow chambers.

Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching measurements

To measure the bound diffusion of NTF2 and mCherry, we measured the diffusion constant within the gel (an average over both bound and free motion). FRAP is a well-established method for measuring diffusion and provided sufficient precision for our needs (32). Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) was performed on gels that had been equilibrated with NTF2 and mCherry. Wash buffer was removed by pipette from the flow chamber reservoir and replaced with 20 μM NTF2-fluorescein and 20 μM mCherry in PTB. The chamber was resealed and equilibrated for 24 h. Photobleaching was then performed with an Olympus IX-81 widefield microscope (Tokyo, Japan) with a Prior Lumen 200 Metal-Halide lamp (Prior Scientific, Cambridge, UK). First, a reference image was taken at 4× magnification. A circular region of the gel ∼300 μm in radius was then photobleached using a 5-s exposure at full power through a DAPI (352–402 nm excitation/417–477 nm emission) filter cube at 40× magnification. After the bleach, the 4× objective was rapidly returned and a time series recorded in FITC and TRITC channels with a Hamamatsu ORCA-ER C4742-80 camera (Hamamatsu City, Japan). A typical series consisted of 15–30 frames recorded as rapidly as possible (5–10 s per frame), followed by 30–60 frames recorded at 1–2 min per frame. The total experiment time was 1–4 h. Typical exposure times were 10 ms (FITC) and 40 ms (TRITC), both with a gain of 3 dB.

The fluorescence recovery curve was created by calculating the average intensity in the bleach spot as a function of time and dividing that value by the average intensity of the entire gel over time. This normalization method compensates for photobleaching during recovery, as verified by simulating data with varying photobleaching rate.

Fluorescence recovery curve fitting

FRAP analysis of systems with both diffusion and binding differs based on the relative timescales of diffusion and reaction kinetics. Three basic regimes have been identified: diffusion dominant, effective diffusion, and reaction dominant (33,34). Our system falls into the effective diffusion regime, in which the reaction is fast relative to diffusion. In this case, a pure diffusion model can be used with an effective diffusion constant. Previously developed models do not account for continual exchange between the gel and surrounding reservoir (34, 35, 36, 37). Because this exchange is significant over the timescale of our experiments, we modeled fluorescence recovery using a full time-dependent Fourier series solution to the diffusion equation.

We solved the diffusion equation in a circular region of radius a, centered at the origin, whose boundary is held fixed at concentration c = 0. The first postbleach image is used as the initial concentration distribution f(r, θ) in the region r < a. Green’s function integrals for the appropriate boundary conditions (38) allow the concentration c(r, θ) to be calculated for r < a. The full solution to the diffusion equation within the gel is given by

| (1) |

where (αa) are the zeros of the Bessel function of the first kind Jν (and its derivative ) and bν,α are weighting constants described below. The sums run over all positive and negative integer Bessel orders and over all zeros of each Bessel function. The boundary is held at c = 0, so it must be shifted by an offset to match the experimental concentration at the boundary, taken to be just within the gel. The area of the gel visible within the microscope image is denoted Ω. Rewriting Eq. 1 to remove the unprimed coordinates from the integral, the mode coefficients Cν,α and Sν,α can then be defined as

| (2) |

with

| (3) |

| (4) |

The weighting constants bν,α would be equal to 2/πa2 for every mode if the entire gel were within the field of view of the microscope, which is not always the case. To compensate for the area outside of the field of view, they are instead given by

| (5) |

| (6) |

The mode coefficients were calculated numerically. The polar coordinates (r, θ) were converted to Cartesian (x, y), and a sum was taken over all the pixels of the initial postbleach image f(x, y) within Ω. The origin was set at the center of the gel, and a was estimated numerically. Before calculating the mode coefficient, the average intensity of the equilibrated portions of the gel was subtracted from the entire image, effectively setting the zeroth order coefficient to zero. The sum was scaled using the area per pixel and normalized using the weighting constants bν,α.

Once the mode coefficients were calculated, the series solution was constructed using Eq. 2. The average intensity of the bleach spot over time (D, t) was determined by integrating the series solution over the bleach spot:

| (7) |

where ΩB is the bleach spot and AB is its total area. The average intensity of the gel (D, t) was determined similarly. The equilibrium concentration c0 was added back to both, and the two values were divided to represent the normalized intensity of the bleach spot over time. Two additional parameters, c1 and c2, were incorporated to reflect the bleach depth and final recovered concentration. Finally, the recovery curve was fitted to the equation

| (8) |

The values of c1 and c2 were of order unity and were not used in further analysis. The diffusion constant D was used to determine the bound diffusion constant as described below.

Partition coefficient analysis

To calculate a protein’s bound diffusion constant within a gel, we determined both the diffusion constant within the gel and the fraction of time the protein is bound. The partition coefficients of NTF2 and mCherry (Fig. 2) can be used to calculate the fraction of time that NTF2 spends bound within the FG gels. When the system is in equilibrium, the concentration of free transport factor (T), free Nup (N), and transport factor-Nup complex (C) is related to the dissociation constant KD by KD = NT/C ≈ NtT/C in the linear approximation N ≈ Nt, which holds when few of the FG motifs are bound. The total tethered Nup concentration, both free and bound, is Nt. The fraction of transport factors that are bound is then given by

| (9) |

Figure 2.

(A) Schematic of partition coefficient γ shown for a binding protein (γ > 1, green solid line) and nonbinding protein (γ < 1, red dashed line). (B) Images of equilibrated circular gels and the surrounding reservoir in NTF2 (left, green) and mCherry (right, red) channels are given. Scale bars, 500 μm. (C) Fluorescence intensity profile of a gel containing FSFG12 and equilibrated with NTF2 and mCherry is shown. Intensity profile is normalized to reservoir intensity. (D) Mean partition coefficients of NTF2 and mCherry for control, FSFG6, and FSFG12 gels are shown. (E) Mean bound fraction pB for control, FSFG6, and FSFG12 gels is shown. All error bars are standard error of the mean. To see this figure in color, go online.

The concentrations of the inert protein and the transport factor in the reservoir are equal and given by T0. The total transport factor concentration within the gel is Tt = T + C and is constant. If γT is the partition coefficient of the transport factor and γI that of the inert protein, then the transport factor concentration can be expressed as

| (10) |

| (11) |

Therefore, within the gel, at chemical equilibrium the bound probability can be expressed in terms of the partition coefficients as

| (12) |

Therefore, we measured pB using the partition coefficients of the transport factor and inert protein, as determined from their equilibrated intensity within the gel as compared to that in the reservoir.

Binding kinetics calculations

Comparison to theory requires an estimate of the off rate koff of the transport factor-Nup interaction. The off-rate calculation uses the relation between Nup concentration and dissociation constant

| (13) |

We assumed a diffusion-limited on-rate constant of kon = 109 s−1 M−1 (24,39). We were unable to directly measure the tethered FG Nup concentration Nt, but we were able to place upper and lower bounds on its value as described below. Using the upper bound of Nt = 0.67 mM for both FSFG6 and FSFG12 gels, we calculated a dissociation constant of KD = 300 ± 80 μM and an off rate of koff = 3.0 × 105 ± 0.8 × 105 s−1 for FSFG6. The corresponding values for FSFG12 are KD = 180 ± 20 μM and koff = 1.8 × 105 ± 0.2 × 105 s−1.

Tether concentration and spacing

Knowledge of the tether concentration is necessary both for the binding kinetics calculation described above and to ensure that the contribution of interchain hopping to bound diffusion is minimized. Isolating the effect of tethered diffusion requires that transport factors be unlikely to interact with two tethers simultaneously, a condition that is met if the tether spacing is larger than the mean tether end-to-end distance. However, the sensitivity of our measurement also decreases with decreasing concentration. As a balance between these two effects, we designed our gels so that if all of the protein we introduced into the precursor solution is incorporated into the gels, the tether spacing would be at most equal to the mean end-to-end length, as expected from a worm-like chain model.

To within the error of a BCA assay, the concentration of both FSFG6 and FSFG12 introduced into the gel is Nt = 0.67 mM, giving an average spacing between tethers of 14 nm. To estimate the mean tether end-to-end length, we treated FSFG6 and FSFG12 as worm-like chains with persistence length = 1 nm and contour lengths of Lc = 50 nm and 100 nm, respectively. The root mean-square end-to-end chain length is then given by (40)

| (14) |

Using this model, FSFG6 is ∼10 nm across and FSFG12 14 nm.

We confirmed significant incorporation of the protein into the gel by 1) the binding of NTF2 to the gel, which predicts that all of the protein is incorporated, and 2) digesting the protein out of the gel using trypsin and measuring the resulting concentration in equilibrated solution. Note that the protein lacks any tyrosine and tryptophan residues, making only indirect techniques available. FG gels were soaked in a large volume of buffer to remove any free FSFG and then subjected to trypsin digestion (41,42). The digested FSFG fragments were extracted and dried in a vacuum desiccator and their concentration quantified with a BCA assay. The final trypsin concentration of the sample was calculated to be ∼10-fold below the BCA detection limit, a conclusion which was supported by the results of a trypsin-only sample in which no protein was detected. This assay resulted in a lower bound of 50 μM (FSFG6) and 70 μM (FSFG12) on the concentration of tethers, giving a mean spacing of 32 nm (FSFG6) and 29 nm (FSFG12). The mean spacing between tethers therefore falls between 14 nm (upper bound, Nt = 0.67 mM) and 32 nm (lower bound, Nt = 50 μM) for FSFG6 and between 14 and 29 nm (Nt = 70 μM) for FSFG12, as compared to the 10 and 14 nm end-to-end distance of FSFG6 and FSFG12, respectively.

To determine the effects of handoffs of NTF2 directly from one FSFG chain to another, we used the measured lower bound on the chain spacing in our previously published simulations (13) to measure the increase in diffusion in the presence of this effect. Those simulations include the intrinsic diffusion of the transport factor in the unbound state, the restriction on the diffusion in the bound state while being confined to a harmonic potential well, and transitions directly from one potential well to an adjacent well. The latter models hopping of multivalent transport factors between FG chains without unbinding. We used a hopping rate near that predicted in simulations (14) of 0.3 μs−1 for FSFG6 and 0.4 μs−1 for FSFG12. In our simulations, hopping led to a ∼2 and ∼7% increase in the bound diffusion coefficient relative to that of tethered diffusion alone for FSFG6 and FSFG12, respectively. Combined, these measurements indicate that tethered diffusion will be the predominant mechanism of bound diffusion.

Results and Discussion

Although previous work has shown that bound diffusion can lead to selective filtration (16, 17, 18), the molecular mechanisms that contribute to bound mobility and their relative importance remain poorly understood (13,20). We focus on determining whether binding to flexible tethers can lead to appreciable bound motion. Transient binding to flexible molecular tethers is a feature of a number of biofilters (8,43,44), suggesting that tethered diffusion is a fundamental molecular mechanism that could be applicable in a variety of systems. Additionally, tethered diffusion could be used to design artificial selective filters.

To test the feasibility of tethered diffusion as a mechanism for bound mobility, we designed a material that displays tethered diffusion using a minimal set of biological components. Our basic design is a hydrogel with covalently attached FG Nups. We allow a transport factor and inert control protein to equilibrate within the gel. We photobleach a portion of the gel and measure the average diffusion constant. The average diffusion is the combination of free and bound diffusion, which we differentiate by measuring the fraction of time bound using the partitioning of the transport factor to the gel, and the free diffusion constant, which we take to be that of our control. In designing these experiments, we assume that the only difference between the transport factor and the control is binding. The partitioning and free diffusion of control and transport factor are assumed to be the same.

We designed our material using key components of the NPC, FG Nups and a transport factor (Fig. 1). The binding kinetics of some transport factor-FG Nup pairs are diffusion limited, significantly faster than many protein-protein binding interactions, because of the rapid polymer dynamics of the intrinsically disordered FG Nup and because the polymer contains many binding sites for the transport factor (24,39). We chose an FG Nup fragment and transport factor pair whose interactions are very well characterized, with the rapid dynamics and moderate affinity required to give significant bound diffusion (24,25,39). The transport factor, NTF2, is a 28-kDa homodimer that is responsible for the transport of Ran through the NPC (45,46). As an inert comparison protein, we chose mCherry, a similarly sized but nonbinding red fluorescent protein. We have assumed that any differences in interactions of mCherry and NTF2 with the gels arise from NTF2 binding to the FG Nups. Our theory of tethered diffusion predicts that the bound diffusion constant should be affected by the length of the FG Nup fragment and the affinity of transport factor-FG Nup interactions. To quantitatively test the model’s predictions, we used as tethers two well-characterized peptides derived from the FG Nup Nsp1, FSFG6 (lc = 50 nm) and FSFG12 (lc = 100 nm) (Fig. 1 A; Materials and Methods) (24,25).

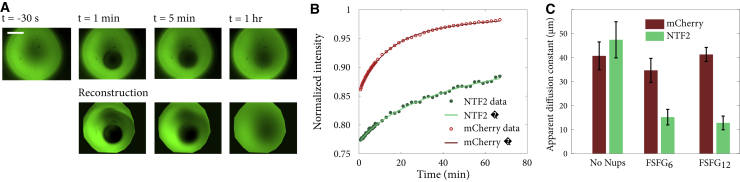

Several approaches can be used to measure bound diffusion. For example, both single-molecule and bulk measurements have been used to measure the bound diffusion of transcription factors (47, 48, 49). We chose to measure the bulk diffusion of particles within a uniform macroscopic material because the binding lifetime and distance traveled during a binding event are sufficiently short so as to make single-molecule measurements difficult. Our bulk material consisted of polyacrylamide gels containing FG Nup fragments. A precursor solution containing acrylamide monomers, bisacrylamide cross-linkers, and bisacrylamide-labeled FSFG was added in microliter droplets to a flow chamber and polymerized through exposure to ultraviolet illumination (Fig. 1 C). The resultant gels were circular (Figs. 1 D and 2 B). A solution containing equimolar concentrations of fluorescent NTF2 and mCherry was introduced to the reservoir surrounding the gel (Fig. 1 D). After a 24-h equilibration period, we photobleached a circular spot in the gels (dark spot in Fig. 3 A within the green hydrogel). The redistribution of fluorescent molecules (FRAP) within the gel was measured and fitted to solutions of the diffusion equation with the experimental geometry. In control gels in the absence of FG Nups, NTF2 and mCherry showed similar partition and diffusion constants (Figs. 2 D and 3 C), and gels made from multiple protein purifications and conjugation reactions gave consistent results (Supporting Materials and Methods). We did see some variability between gels, which we attribute to slight changes in reagent concentrations and oxygen concentration within our solutions.

Figure 3.

(A) Circular hydrogels were bleached near their center with a nearly circular bleach spot. The top row is images from the NTF2 channel of a gel containing FSFG6, and the bottom row is a simulation of the same data used to extract the effective diffusion coefficient. Scale bars, 500 μm. (B) Normalized recovery curves and Fourier series fit for gel shown in (A) are given. (C) Diffusion constant for NTF2 and mCherry in each experimental condition is shown. Error bars are standard error of the mean. To see this figure in color, go online.

Our experiments were designed to isolate tethered diffusion and to avoid other possible sources of bound diffusion. These could include other features known to be important to nuclear transport such as FG Nup cohesiveness (50,51), active release of cargo and transport factors from the pore (10,52,53), and contributions of crowding and transport factors themselves to maintaining the selective barrier (54,55). To retain only the features of the NPC that contribute to tethered diffusion, we chose an FG Nup fragment that is not cohesive (56) and for which we previously saw no aggregation or liquid phase separation at concentrations up to 20 mg/mL (24). We omitted proteins that could contribute to active release (e.g., Ran). Multivalent FG Nup-transport factor interactions could permit transport factors to move between nearby Nups without fully unbinding (14,15) or to cross-link adjacent FG Nups, altering the barrier properties of the gel (54). These effects should only be important to bound-state diffusion if the density of FG Nups within the gel is large enough that a transport factor is likely interact with two FG Nups at once. By tuning the average concentration of tethered FG Nups within the gels, we developed gels in which the mean tethered peptide spacing is larger than its end-to-end distance (see Materials and Methods). Therefore, the predominant mechanism of bound-state mobility in these gels should be tethered diffusion.

To determine the bound diffusion constant of a protein within an FG gel, we require knowledge only of the fraction of time the protein spends bound to FSFG and its diffusion constant arising from both bound and free motion. The bound fraction can be calculated from the partition coefficient. A protein’s partition coefficient γ is the ratio of its concentration within an equilibrated gel to that in the surrounding reservoir (Fig. 2 A). We equilibrated the gels with equimolar concentrations of mCherry and NTF2. The partition coefficients were measured in equilibrated gels by comparing the intensity within the gel to that of the reservoir. NTF2 and mCherry partitioned similarly into gels that contained no FG Nups, indicating that both proteins interact similarly with the inert polyacrylamide gel scaffold (Fig. 2 D). The mCherry partition coefficient remained nearly the same in both FG-containing gels as in the control gels without FG Nups. This indicates that the FG Nup neither occupies a significant fraction of the gel volume nor significantly alters the gel properties. The partition coefficient of NTF2 increased dramatically in the presence of FSFG6 and FSFG12, consistent with binding. The fraction bound is given by the selective enrichment of NTF2 relative to mCherry in the gels due to binding (Eq. 12; Fig. 2 E).

We used FRAP to measure the diffusion constant of mCherry and NTF2 within the gels. FRAP relies on the gradual redistribution of fluorescent transport factors after a region of the gel is photobleached; the recovery time of the bleached region is related to the transport factor’s diffusion constant (32). In some cases, the recovery time can be well fitted by simple models of diffusion and binding. However, in our experiments, there was significant exchange between the gel and the reservoir, and the gels were not always fully equilibrated. To accurately measure the diffusion constant with these confounding effects, we used a time-dependent, two-dimensional Fourier series solution to the diffusion equation (38). The two-dimensional postbleach concentration profile was taken as the initial condition. We calculated the appropriate Fourier coefficients and then simulated the time-dependent recovery of the bleached region. This approach gave reconstructed images and recovery curves consistent with those observed experimentally (Fig. 3, A and B). The diffusion constant was extracted from the fits for both NTF2 and mCherry in all three gel conditions (Fig. 3 C). The diffusion constants for the transport factor and inert protein were roughly equal in the control gels, indicating that there is no significant difference between the proteins in their interaction with the polyacrylamide scaffold (p = 0.61). The transport factor, NTF2, had a lower diffusion constant in the gels containing FG Nups, as expected, because motion is slowed during binding events.

To determine the bound diffusion constant, we assumed that the diffusion constant D of NTF2 is given by a weighted average of the free and bound diffusion constants because NTF2-FSFG binding is fast relative to the diffusion of NTF2. The diffusion coefficient is given by

| (15) |

where DB is the bound diffusion constant of NTF2, DF is its free diffusion constant (while unbound), and pB is the fraction of time that NTF2 spends bound. Because we cannot directly measure the diffusion constant of NTF2 in the unbound state and the diffusion constants of mCherry and NTF2 are very similar in control gels, we assumed the free diffusion constant of the transport factor to be equal to the diffusion of the inert protein mCherry. Using this assumption, we extracted the bound diffusion constant using Eq. 15.

We measured significant bound diffusion for NTF2 in both FG-Nup-containing gels (Fig. 4). The bound diffusion constant of NTF2 in the FSFG6 gels was 5.6 ± 2.2 μm2/s (DB/DF = 0.24 ± 0.09), and in the FSFG12 gels, it was 5.2 ± 3.2 μm2/s (DB/DF = 0.13 ± 0.08). These results demonstrate that biomaterials which feature transient binding to dynamic polymers can display bound-state diffusion.

Figure 4.

Model predictions and experimental measurements of the bound diffusion constant DB for NTF2 in the FSFG6 and FSFG12 gels. The tethered diffusion model (Eq. 16) was used for the predictions, assuming a tether concentration of 0.67 mM in both conditions and a diffusion-limited on-rate constant of 109 M−1 s−1. The predicted value of DB was computed for each gel and averaged for each condition. Error bars are standard error of the mean of calculated bound diffusion constant for each gel. To see this figure in color, go online.

We previously predicted the expected bound diffusion constant arising from tethered diffusion (13). In this theory, the protein was modeled as diffusing in a harmonic potential well representing the tether to which it is bound. The bound diffusion is determined by the mean-square displacement of a particle during a binding event weighted by the probability of that binding lifetime. The resulting bound diffusion constant is given by

| (16) |

where LC is the tether contour length, is its persistence length, and koff is the off rate of the interaction between the transport factor and FG Nup. The persistence length of disordered proteins is ∼1 nm (57), and the tether contour length is ∼50 nm for FSFG6 and ∼100 nm for FSFG12. The off rate, koff, was estimated using the maximal possible tethered FG Nup concentration (see Materials and Methods) and a diffusion-limited on rate (24,39). We calculate a mean maximal dissociation constant of KD = 24 ± 6 μM for FSFG6 and KD = 304 ± 78 μM for FSFG12. These values are significantly lower (tighter) than those recently measured by NMR and isothermal titration calorimetry (25), which may be due to the crowded gel environment. With these assumptions, the predicted value of DB was calculated for each gel using Eq. 16 and then averaged (Fig. 4).

For both FSFG6 and FSFG12, the measured value of bound diffusion constant is consistent with the value predicted by our minimal model of tethered diffusion. Although FSFG12 is twice as long as FSFG6, the affinity is also weaker. Because the bound diffusion constant only depends on the product LCkoff, the bound diffusion constant in the FSFG12 gel is only expected to be slightly higher than that in the FSFG6 gel (Fig. 4).

Conclusions

Biological filters are necessary for cells and organisms to control the localization of macromolecules. They are typically made of flexible polymers that provide a selective barrier, allowing the passage of some macromolecules while inhibiting the passage of others (8,43,44). Bound-state diffusion is necessary for the selective enhancement of the steady-state flux for binding particles relative to similar inert particles (13,16, 17, 18). In the case of the NPC, those particles that are able to passage the barrier often have relatively weak affinities and rapid binding dynamics (24,39). The combination of binding to sites on flexible polymers with rapid binding dynamics is thought to be sufficient for significant diffusion even within the bound state, an effect termed tethered diffusion (13).

To experimentally determine whether bioinspired gels could be designed to utilize tethered diffusion, we tethered FG Nup fragments to polyacrylamide gels and measured the diffusion and binding properties of a transport factor (NTF2) and comparable inert protein (mCherry) (Fig. 1). We designed our gels to allow for accurate measurement of the partition coefficient (and thus the fraction of time bound; Fig. 2) and diffusion constant (Fig. 3), the two parameters needed to determine the bound diffusion. By design, the polyacrylamide gel scaffold interacts similarly with both test proteins, leading to diffusion constants and partition coefficients that are similar in control gels lacking FG Nups. Binding increases the concentration of NTF2 in the gel. The bound motion results in a moderate increase in diffusion of NTF2 within the gel. The binding also significantly increases the concentration of NTF2. The combination of bound motion and an increase in concentration due to binding increases the flux of the binding species at steady state. The bound diffusion constants of NTF2 calculated using the diffusion constants obtained by FRAP are quantitatively consistent with theoretical predictions of diffusion while bound to flexible tethers (Fig. 4; (13)).

These results represent a first step toward understanding and utilizing tethered diffusion in biological and bioinspired systems. Although our system utilizes components of cells’ nuclear transport machinery, the requirements of rapid binding kinetics and binding site flexibility are present in other systems. Tethered diffusion may be used to engineer artificial bioinspired filters or to manipulate the flux of particles through naturally occurring filters such as mucus membranes. Binding interactions can be used to impart selectivity, whereas tethered diffusion would allow for particle motion necessary for the particle to penetrate into and across a barrier.

Author Contributions

L.E.H., M.D.B., and L.M. designed the research and wrote the article. L.M. carried out the experiments and analyzed the data.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Joseph Dragavon (BioFrontiers Advanced Light Microscopy Core) for assistance with microscopy and Eric Verbeke, Sadhana Sharma, Stephanie Bryant, Benjamin Fairbanks, and Nathan Crossette for assistance with gel design and fabrication.

This work is supported by National Institutes of Health grant R35 GM119755, National Science Foundation grant DMR-1551095, National Science Foundation grant MRSEC DMR-1420736, the Boettcher Foundation, and a CU innovative seed grant.

Editor: David Eliezer.

Footnotes

Supporting Material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2019.11.026.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Lai S.K., Suk J.S., Hanes J. Drug carrier nanoparticles that penetrate human chronic rhinosinusitis mucus. Biomaterials. 2011;32:6285–6290. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schneider A.F.L., Hackenberger C.P.R. Fluorescent labelling in living cells. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2017;48:61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2017.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang X., Chisholm J., Hanes J. Protein nanocages that penetrate airway mucus and tumor tissue. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:E6595–E6602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1705407114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ribbeck K., Görlich D. Kinetic analysis of translocation through nuclear pore complexes. EMBO J. 2001;20:1320–1330. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.6.1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mohr D., Frey S., Görlich D. Characterisation of the passive permeability barrier of nuclear pore complexes. EMBO J. 2009;28:2541–2553. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Timney B.L., Raveh B., Rout M.P. Simple rules for passive diffusion through the nuclear pore complex. J. Cell Biol. 2016;215:57–76. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201601004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strambio-De-Castillia C., Niepel M., Rout M.P. The nuclear pore complex: bridging nuclear transport and gene regulation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010;11:490–501. doi: 10.1038/nrm2928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jovanovic-Talisman T., Zilman A. Protein transport by the nuclear pore complex: simple biophysics of a complex biomachine. Biophys. J. 2017;113:6–14. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tagliazucchi M., Peleg O., Szleifer I. Effect of charge, hydrophobicity, and sequence of nucleoporins on the translocation of model particles through the nuclear pore complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:3363–3368. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1212909110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zilman A., Di Talia S., Magnasco M.O. Efficiency, selectivity, and robustness of nucleocytoplasmic transport. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2007;3:e125. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tu L.C., Fu G., Musser S.M. Large cargo transport by nuclear pores: implications for the spatial organization of FG-nucleoporins. EMBO J. 2013;32:3220–3230. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ro S., Gopinathan A., Kim Y.W. Interactions between a fluctuating polymer barrier and transport factors together with enzyme action are sufficient for selective and rapid transport through the nuclear pore complex. Phys. Rev. E. 2018;98:012403. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.98.012403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maguire L., Stefferson M., Hough L.E. Design principles of selective transport through biopolymer barriers. Phys. Rev. E. 2019;100:042414. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.100.042414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raveh B., Karp J.M., Cowburn D. Slide-and-exchange mechanism for rapid and selective transport through the nuclear pore complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:E2489–E2497. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1522663113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang Y.J., Mai D.J., Olsen B.D. Nucleopore-inspired polymer hydrogels for selective biomolecular transport. Biomacromolecules. 2018;19:3905–3916. doi: 10.1021/acs.biomac.8b00556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wyman J. Facilitated diffusion and the possible role of myoglobin as a transport mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 1966;241:115–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cussler E.L., Aris R., Bhown A. On the limits of facilitated diffusion. J. Membr. Sci. 1989;43:149–164. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berezhkovskii A.M., Pustovoit M.A., Bezrukov S.M. Channel-facilitated membrane transport: transit probability and interaction with the channel. J. Chem. Phys. 2002;116:9952–9956. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bickel T., Bruinsma R. The nuclear pore complex mystery and anomalous diffusion in reversible gels. Biophys. J. 2002;83:3079–3087. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(02)75312-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fogelson B., Keener J.P. Enhanced nucleocytoplasmic transport due to competition for elastic binding sites. Biophys. J. 2018;115:108–116. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2018.05.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fogelson B., Keener J. Transport facilitated by rapid binding to elastic tethers. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 2019;79:1405–1422. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siebrasse J.P., Peters R. Rapid translocation of NTF2 through the nuclear pore of isolated nuclei and nuclear envelopes. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:887–892. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kiskin N.I., Siebrasse J.P., Peters R. Optical microwell assay of membrane transport kinetics. Biophys. J. 2003;85:2311–2322. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(03)74655-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hough L.E., Dutta K., Cowburn D. The molecular mechanism of nuclear transport revealed by atomic-scale measurements. eLife. 2015;4:10027. doi: 10.7554/eLife.10027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hayama R., Sparks S., Cowburn D. Thermodynamic characterization of the multivalent interactions underlying rapid and selective translocation through the nuclear pore complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2018;293:4555–4563. doi: 10.1074/jbc.AC117.001649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Magnusdottir A., Johansson I., Berglund H. Enabling IMAC purification of low abundance recombinant proteins from E. coli lysates. Nat. Methods. 2009;6:477–478. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0709-477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hou J., Shi Q., Yin J. Micropatterning of hydrophilic polyacrylamide brushes to resist cell adhesion but promote protein retention. Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 2014;50:14975–14978. doi: 10.1039/c4cc03994g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gao W., Vecchio D., Zhang L. Hydrogel containing nanoparticle-stabilized liposomes for topical antimicrobial delivery. ACS Nano. 2014;8:2900–2907. doi: 10.1021/nn500110a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ratner B.D., Hoffman A.S. Volume 31. American Chemical Society; 1976. Synthetic hydrogels for biomedical applications; pp. 1–36. (Hydrogels for Medical and Related Applications). ACS Symposium Series. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murakami Y., Maeda M. DNA-responsive hydrogels that can shrink or swell. Biomacromolecules. 2005;6:2927–2929. doi: 10.1021/bm0504330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fairbanks B.D., Schwartz M.P., Anseth K.S. A versatile synthetic extracellular matrix mimic via thiol-norbornene photopolymerization. Adv. Mater. 2009;21:5005–5010. doi: 10.1002/adma.200901808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Axelrod D., Koppel D.E., Webb W.W. Mobility measurement by analysis of fluorescence photobleaching recovery kinetics. Biophys. J. 1976;16:1055–1069. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(76)85755-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sprague B.L., Pego R.L., McNally J.G. Analysis of binding reactions by fluorescence recovery after photobleaching. Biophys. J. 2004;86:3473–3495. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.103.026765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carrero G., Crawford E., de Vries G. Characterizing fluorescence recovery curves for nuclear proteins undergoing binding events. Bull. Math. Biol. 2004;66:1515–1545. doi: 10.1016/j.bulm.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carrero G., McDonald D., Hendzel M.J. Using FRAP and mathematical modeling to determine the in vivo kinetics of nuclear proteins. Methods. 2003;29:14–28. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(02)00288-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kang M., Day C.A., Kenworthy A.K. A quantitative approach to analyze binding diffusion kinetics by confocal FRAP. Biophys. J. 2010;99:2737–2747. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kang M., Day C.A., DiBenedetto E. Simplified equation to extract diffusion coefficients from confocal FRAP data. Traffic. 2012;13:1589–1600. doi: 10.1111/tra.12008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carslaw H.S., Jaeger J.C. Second Edition. Clarendon Press; Oxford: 1959. Conduction of Heat in Solids. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Milles S., Mercadante D., Lemke E.A. Plasticity of an ultrafast interaction between nucleoporins and nuclear transport receptors. Cell. 2015;163:734–745. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Howard J. First Edition. Sinauer Associates; Sunderland, MA: 2001. Mechanics of Motor Proteins and the Cytoskeleton. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shevchenko A., Tomas H., Mann M. In-gel digestion for mass spectrometric characterization of proteins and proteomes. Nat. Protoc. 2006;1:2856–2860. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gundry R.L., White M.Y., Van Eyk J.E. Preparation of proteins and peptides for mass spectrometry analysis in a bottom-up proteomics workflow. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. 2009;Chapter 10:Unit10.25. doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb1025s88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Witten J., Ribbeck K. The particle in the spider’s web: transport through biological hydrogels. Nanoscale. 2017;9:8080–8095. doi: 10.1039/c6nr09736g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lieleg O., Baumgärtel R.M., Bausch A.R. Selective filtering of particles by the extracellular matrix: an electrostatic bandpass. Biophys. J. 2009;97:1569–1577. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ribbeck K., Lipowsky G., Görlich D. NTF2 mediates nuclear import of Ran. EMBO J. 1998;17:6587–6598. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.22.6587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bayliss R., Ribbeck K., Stewart M. Interaction between NTF2 and xFxFG-containing nucleoporins is required to mediate nuclear import of RanGDP. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;293:579–593. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bhattacharya D., Mazumder A., Shivashankar G.V. EGFP-tagged core and linker histones diffuse via distinct mechanisms within living cells. Biophys. J. 2006;91:2326–2336. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.079343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stasevich T.J., Mueller F., McNally J.G. Dissecting the binding mechanism of the linker histone in live cells: an integrated FRAP analysis. EMBO J. 2010;29:1225–1234. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen J., Zhang Z., Liu Z. Single-molecule dynamics of enhanceosome assembly in embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2014;156:1274–1285. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Frey S., Görlich D. A saturated FG-repeat hydrogel can reproduce the permeability properties of nuclear pore complexes. Cell. 2007;130:512–523. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vovk A., Gu C., Zilman A. Simple biophysics underpins collective conformations of the intrinsically disordered proteins of the Nuclear Pore Complex. eLife. 2016;5:e10785. doi: 10.7554/eLife.10785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lowe A.R., Siegel J.J., Liphardt J.T. Selectivity mechanism of the nuclear pore complex characterized by single cargo tracking. Nature. 2010;467:600–603. doi: 10.1038/nature09285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mincer J.S., Simon S.M. Simulations of nuclear pore transport yield mechanistic insights and quantitative predictions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:E351–E358. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104521108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lowe A.R., Tang J.H., Liphardt J.T. Importin-β modulates the permeability of the nuclear pore complex in a Ran-dependent manner. eLife. 2015;4:e04052. doi: 10.7554/eLife.04052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kapinos L.E., Schoch R.L., Lim R.Y.H. Karyopherin-centric control of nuclear pores based on molecular occupancy and kinetic analysis of multivalent binding with FG nucleoporins. Biophys. J. 2014;106:1751–1762. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yamada J., Phillips J.L., Rexach M.F. A bimodal distribution of two distinct categories of intrinsically disordered structures with separate functions in FG nucleoporins. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2010;9:2205–2224. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M000035-MCP201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Receveur-Bréchot V., Durand D. How random are intrinsically disordered proteins? A small angle scattering perspective. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2012;13:55–75. doi: 10.2174/138920312799277901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.