The application of traditional medicine, including traditional Persian medicine (TPM), is characterised by a long history. A review of the background of medicine in Iran dates back to the field of traditional practice, and the history of the medical profession in this region shows the evolution and development of the field over its thousand-year history.1, 2, 3 The peak of TPM growth is discussed in valuable sources, such as Avicenna’s The Canon of Medicine, which has been used for many years as a reference book in medical schools of prestigious universities around the world.4, 5 Access to traditional, complementary and alternative medicine has been growing in the past years globally, and Iran is no exception as one of the leading countries in this respect. There is an increasing tendency to use the suggested therapeutic approaches of TPM in the treatment of various diseases,6, 7, 8 but an important consideration is that the unreasonable, non-scientific and evidence-deficient application of this historical-therapeutic approach may cause complications.9 This possibility prompted many countries, including China, Korea and India, to incorporate the science- and evidence-based use of traditional medical practices in their agendas, and Iran has continued to adhere to these stipulations in recent years.10, 11, 12

The Ministry of Health and Medical Education of Iran has emphasised optimally capitalising on the potential of TPM since 2006. For this purpose and considering records of success across the world, a TPM programme was introduced to university education at the PhD level, with the prerequisite to admission being a medical degree. During these years, 8 colleges, 17 departments and more than 5 research centres that employ about 90 faculty members initiated operations in the country. Approximately 200 physicians have graduated with TPM degrees, and around 300 PhD students are currently studying in the aforementioned institutions. A number of general practitioners have also received short-term training and are engaging in the conventional practice of medicine. Despite this initial upward movement, however, disruptions have emerged from detractors of TPM, thereby negatively affecting the development process.13 Nevertheless, two years after the launch of this discipline at the university context, the first series of randomised clinical trials (RCTs) began to be published internationally.

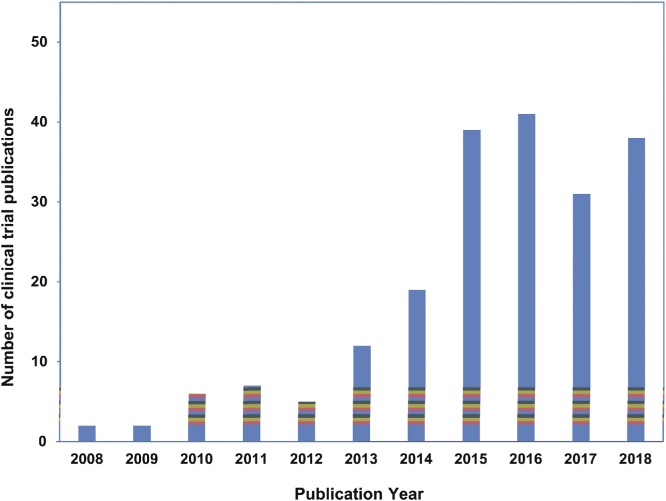

We searched PubMed systematically to investigate the trends that typify the publication of RCTs in the TPM domain from 2008 to 2018. Amongst the trials reviewed, 204 TPM RCTs examined various medical disciplines that range from internal medicine to dental hygiene. The most frequently explored issues were those related to neurology (17.1%), gynaecological diseases (15.8%), endocrine-related diseases (14.9%), psychiatry (9.2%) and gastrointestinal diseases (8.3%). Since 2008 and the academic launch of TPM in Iran, significant preliminary efforts have been carried out to establish colleges, traditional medicine departments, faculty and support infrastructure, thus driving upward progress in the production of RCT articles since 2012 (Fig. 1). In 2017, this pattern plateaued, indicating that the capacity of the educational and research system in Iran to produce new articles has reached a saturation point. This phenomenon can be attributed to the lack of new capacity or to specific circumstances. However, a scrutiny of trends observed since 2012 uncovered an annual increase in printed articles of almost 300%.

Fig. 1.

The randomized clinical trials released during the years 2008–2018 in the TPM domain.

Strengthening infrastructure and launching an academic movement on TPM engendered a rise in the number of published RCTs. The particular focus espoused by health policy makers in the country depends on the culture of a given population and traditional practitioners. Of course, financial support for research and international cooperation in this field is also critical and deserves attention.14, 15

Maintaining, developing and strengthening infrastructure as well as international cooperation and financial support are amongst the most important factors in the continued ascension of RCT production in Iran.16 Non-financial support for maintaining and enhancing the academic perspective of TPM is essential to carrying on with existing scientific achievements and furthering progress in the field. Now, there is a danger that with diminished support and satisfaction with current status, a slowing down or reversal of the upward trend will occur. Given the high and growing prevalence of TPM in Iran, the attention of health policy makers in this area has become increasingly necessary.

This overview covers the quantity of published articles, but the quality of scientific evidence produced is equally important.17 The problem is that no research has thus far evaluated the quality of previous works, so enquiries in this regard would be very valuable. Scientometric studies to evaluate the quality of CAM research reports are warranted.

Authors’ contribution

Both authors have equal role in preparing the manuscript including concept, design, drafting, and final revision.

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest to disclose.

Funding

No external funding was received for the preparation of this editorial.

Data availability

Data will be made available upon request.

Ethical statements

This work does not include humans or animals as subjects.

References

- 1.Withington E.T. Medical history from the earliest times: VII.-Chaldean and persian medicine. Hosp (Lond) 1892;12(293):85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gorji A., Khaleghi Ghadiri M. History of headache in medieval Persian medicine. Lancet Neurol. 2002;1(8):510–515. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(02)00226-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zarshenas M.M., Hosseinkhani A., Zargaran A., Kordafshari G., Mohagheghzadeh A. Ophthalmic dosage forms in medieval Persia. Pharm Hist. 2013;43(1):6–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Avicenna . Soroush Press; Tehran: 2005. Al-Qanun fi al-Tibb (The Canon of Medicine) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zargaran A., Mehdizadeh A., Zarshenas M.M., Mohagheghzadeh A. Avicenna (980–1037 AD) J Neurol. 2012;259(2):389–390. doi: 10.1007/s00415-011-6219-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bordbar M., Pasalar M., Safaei S. Complementary and alternative medicine use in thalassemia patients in Shiraz, southern Iran: A cross-sectional study. J Tradit Complement Med. 2018;8(1):141–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcme.2017.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bordbar M., Pasalar M., Aresehiri R., Haghpanah S., Zareifar S., Amirmoezi F. A cross-sectional study of complementary and alternative medicine use in patients with coagulation disorders in Southern Iran. J Integr Med. 2017;15(5):359–364. doi: 10.1016/S2095-4964(17)60343-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hashempur M.H., Heydari M., Mosavat S.H., Heydari S.T., Shams M. Complementary and alternative medicine use in Iranian patients with diabetes mellitus. J Integr Med. 2015;13(5):319–325. doi: 10.1016/S2095-4964(15)60196-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pasalar M., Akrami R. Excessive attention to major complications in frequent dialysis: A misleading point for patients’ quality of life? Ther Apher Dial. 2016;20(5):537–538. doi: 10.1111/1744-9987.12459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mun S., Lee S., Park K., Lee S.J., Koh B.H., Baek Y. Effect of Traditional East Asian Medicinal herbal tea (HT002) on insomnia: A randomized controlled pilot study. Integr Med Res. 2019;8(1):15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.imr.2018.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee H.Y., Yun Y.J., Yu S.A. A cross-sectional survey of clinical factors that influence the use of traditional Korean medicine among children with cerebral palsy. Integr Med Res. 2018;4(7):333–340. doi: 10.1016/j.imr.2018.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li H., Cao X., Liu Y. Establishment of modified biopharmaceutics classification system absorption model for oral Traditional Chinese Medicine (Sanye Tablet) J Ethnopharmacol. 2019:112148. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2019.112148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pasalar M. Promotion of traditional Persian medicine; a neglected necessity. Arch Iran Med. 2014;17(8):593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khalaf A.J., Aljowder A.I., Buhamaid M.J., Alansari M.F., Jassim G.A. Attitudes and barriers towards conducting research amongst primary care physicians in Bahrain: a cross-sectional study. BMC Fam Pract. 2019;20(1):20. doi: 10.1186/s12875-019-0911-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mansoori P. 50 years of Iranian clinical, biomedical, and public health research: A bibliometric analysis of the Web of Science Core Collection (1965-2014) J Glob Health. 2018;8(2):020701. doi: 10.7189/jogh.08.020701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mansoori P., Majdzadeh R., Abdi Z. Setting research priorities to achieve long-term health targets in Iran. J Glob Health. 2018;8(2):020702. doi: 10.7189/jogh.08.020702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Badakhshan A., Arab M., Rashidian A., Gholipour M., Mohebbi E., Zendehdel K. Systematic review of priority setting studies in health research in the Islamic Republic of Iran. East Mediterr Health J. 2018;24(8):759–763. doi: 10.26719/2018.24.8.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon request.