Abstract

Curcumin (CURC) is a hydrophobic molecule and its water solubility can be greatly improved by liposome encapsulation. However, investigations on the stability of pH-sensitive molecules incorporated into liposomal membranes are limited. In this study, CURC-loaded liposomes with varied internal pH values (pH 2.5, 5.0, or 7.4) were prepared and designated as CURC-LP (pH 2.5), CURC-LP (pH 5.0), and CURC-LP (pH 7.4). Physical properties including particle size, ζ-potential, morphology, entrapment efficiency, and physical stabilities of these CURC-LPs were assessed. In addition, the chemical stability of liposomal CURC to different external physiological environments and internal microenvironmental pH levels were investigated. We found that among these CURC-LPs, CURU-LP (pH 2.5) has the highest entrapment efficiency (73.7%), the best physical stabilities, and the slowest release rate in vitro. Liposomal CURC remains more stable in an acid external environment. In the physiological environment, the chemical stability of liposomal CURC is microenvironmental pH-dependent. In conclusion, we prove that the stability of liposomal CURC is external physiological environment- and internal microenvironmental pH-dependent. These findings suggest that creating an acidic microenvironment in the internal chamber of liposomes is beneficial to the stability of liposomal CURC, as well as for other pH-sensitive molecules.

Introduction

Curcumin (CURC) is a natural yellow pigment derived from the rhizome of the herb Curcuma longa. It exhibits strong anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antitumor, antiviral, antibacterial, and antifungal activities.1−6 Because of these desirable medicinal benefits, especially its antitumor activity, CURC has been a research topic of interest for years.7,8 However, it has a very poor aqueous solubility and low stability in alkaline pH conditions.9−11 These features render CURC poor oral bioavailability and low stability against the physiological environment (neutral pH values). The therapeutic efficacy of CURC is limited, and extensive studies have been devoted to overcoming this limitation.12−15

Liposomes are commonly used as transport vehicles for drugs, proteins, vaccines, and diagnostic agents.16−21 Because liposomes are composed of a hydrophobic lipid bilayer and a hydrophilic inner aqueous chamber, lipophilic drugs can distribute in lipid bilayers at high percentages. Therefore, the solubility of drugs in aqueous media can increase by encapsulating these in liposomes.22−24 For CURC, such incorporation in liposomal membranes may also increase its solubility in water and improve its stability because incorporation in liposomal membranes can protect it against hydrolytic degradation. Several recent studies have confirmed this opinion.25−28

Generally, liposomes are prepared in a neutral buffer solution; therefore, the loaded drug molecules are also in a neutral environment after incorporation into liposomes.29,30 For a pH-sensitive hydrophilic drug located in the inner aqueous chamber of the liposomes, it is easy to understand that its stability would be significantly affected by the microenvironmental pH in the aqueous chamber. However, as a pH-sensitive hydrophobic molecule, whether the stability of CURC incorporated into the liposomal membranes will be affected by the internal microenvironment of the liposomes is quite interesting but lacks adequate research. So far, most of the studies on liposomal CURC have focused exclusively on its biological effectiveness, especially in anticancer treatment, and not much attention has been given to the assessment of its stability.31,32

In the present study, CURC-loaded liposomes with varied internal pH values (pH 2.5, 5.0, or 7.4) were prepared. The chemical stability of liposomal CURC to the different external physiological environments and internal microenvironmental pH values was investigated. This study aimed to establish a novel approach to improve the stability of liposomal CURC.

Results and Discussion

Characterization of LPs

The size, polydispersity index (PDI), and ζ-potential of the three different kinds of LPs are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Size and ζ-Potential of the Three Different Kinds of Liposomesa.

| samples | size (nm) | PDI | ζ-potential (mV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| LP (pH 2.5) | 307.1 ± 24.2 | 0.36 ± 0.06 | –19.15 ± 7.70 |

| LP (pH 5.0) | 339.5 ± 31.8 | 0.38 ± 0.06 | –21.15 ± 2.62 |

| LP (pH 7.4) | 278.2 ± 28.1 | 0.33 ± 0.08 | –9.43 ± 0.66 |

Data are presented as mean ± s.d. (n = 3).

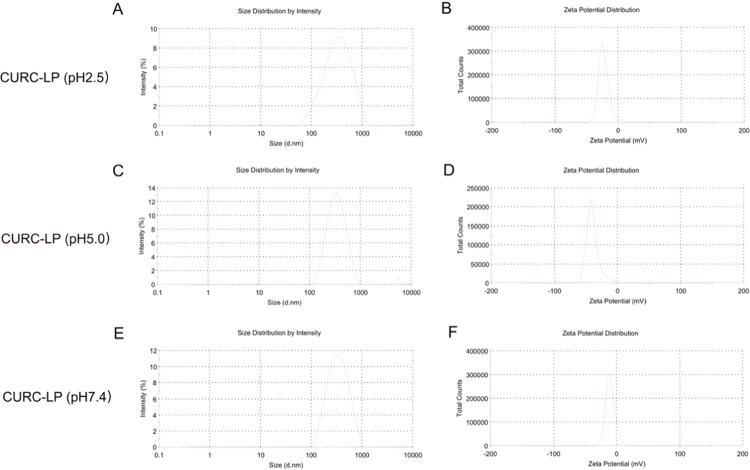

The three different kinds of obtained LPs had similar sizes (around 300 nm). Size distribution is usually also presented as PDI, a numerical value with a range of 0–1, i.e., the lower the better. The PDI of each LP was similar at about 0.3 and shown in Figure 1. In contrast, the ζ-potentials of these LPs were slightly different; the ζ-potentials of LP (pH 2.5) and LP (pH 5.0) were similar at −19.15 ± 7.70 and −21.15 ± 2.62 mV, respectively. However, for LP (pH 7.4), the ζ-potentials were lower (−9.43 ± 0.66). It is assumed that for LP (pH 7.4), the internal environment was more alkaline, leading to lower ζ-potentials. In general, a higher ζ-potential leads to a more stable colloidal suspension. Similar to size distribution, the ζ-potential distribution of all of the three kinds of LPs was narrow, indicating good ζ-potential distribution for every type of LP.

Figure 1.

Typical size and ζ-potential distribution graphs of the three kinds of liposomes. (A, B) LP (pH 2.5), (C, D) LP (pH 5.0), (E, F) LP (pH 7.4).

The morphology of LPs was observed by SEM. Figure 2 shows that the three kinds of LPs were all spherical, and the particle size of every type of LP was evenly distributed, indicating good size distribution, which coincides with the results derived from the DLS measurement.

Figure 2.

SEM images. (A) LP (pH 2.5), (B) LP (pH 5.0), and (C) LP (pH 7.4). Scale bar: 1 μm.

Characterization of CURC-LPs

The size, polydispersity index (PDI), ζ-potential, and encapsulation efficiency of the three kinds of CURC-LPs are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Size, ζ-Potential, and Encapsulation Efficiency of the Three Different Kinds of Curcumin-Loaded Liposomesa.

| samples | size (nm) | PDI | ζ-potential (mV) | encapsulation efficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CURC-LP (pH 2.5) | 324.8 ± 54.1 | 0.27 ± 0.03 | –18.57 ± 3.62 | 73.7 ± 1.6 |

| CURC-LP (pH 5.0) | 342.2 ± 37.1 | 0.27 ± 0.03 | –18.37 ± 2.31 | 40 ± 2.2 |

| CURC-LP (pH 7.4) | 309 ± 37.9 | 0.15 ± 0.03 | –9.15 ± 1.24 | 64 ± 1 |

Data are presented as the mean ± s.d. (n = 3).

The size of every CURC-LP was larger than LPs prepared from the same internal microenvironmental pH values. Interestingly, the PDI of CURC-LPs was lower, which means the particle size of CURC-LPs was more evenly distributed than LPs. However, for ζ-potential, there were no obvious differences between the CURC-LPs and LPs prepared using the same internal microenvironmental pH values. Typical size and ζ-potential distribution graphs of the three kinds of CURC-LPs are shown in Figure 3. The EE of the CURC was 73.7 ± 1.6, 40 ± 2.2, and 64 ± 1% with respect to CURC-LP (pH 2.5), CURC-LP (pH 5.0), and CURC-LP (pH 7.4). The EE of CURC-LP (pH 2.5) was the highest, indicating that internal microenvironmental pH 2.5 is optimal for liposomal CURC compared with pH 5.0 and 7.4 in terms of EE. This may be related to the solubility and stabilities of CURC in different environmental acid/alkali solvents.

Figure 3.

Typical size and ζ-potential distribution graphs of the three kinds of CURC-liposome. (A, B) CURC-LP (pH 2.5), (C, D) CURC-LP (pH 5.0), and (E, F) CURC-LP (pH 7.4).

Physical Stability of LPs

The physical stability of LPs is very important for their storage, safety, and application. LPs are colloidal systems and their physical stability can be assessed in terms of colloidal stability. Particle aggregation (thermodynamic instability) is an essential feature of colloidal instability. Thus, in this study, we investigated the thermodynamic stabilities of three kinds of LPs by monitoring changes in particle size. The measured size at the fixed time intervals compared to the initial size is the relative size, as shown in Figure 4A.

Figure 4.

Stability of the three kinds of liposomes over a 48 h period at 37 °C. (A) Thermodynamic stability of liposomes by assessing changes in particle size and (B) size changes after incubation with an equal volume of FBS and PBS (pH 7.4, 0.001 M) within 48 h. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3).

We can see that the relative sizes of the three kinds of LPs were relatively stable within 48 h. There was no significant statistical difference within every time point for any kind of LP. These results indicate that the size of every type of LP did not significantly change for at least 48 h. Thus, all three kinds of LPs had high thermodynamic stability for at least 48 h at 37 °C. This suggests that the internal microenvironmental pH values do not influence the physical stability of LPs.

Chemical Stability of LPs in FBS

The chemical stability of LPs in serum is also very important when LPs are used in vivo. Once LPs enter the blood, these adsorb onto plasma proteins or aggregate with each other, leading to a change in the LPs and initially present as an increase in particle size. The measured size at the fixed time intervals compared to the initial size is shown in Figure 4B. For all of the three kinds of LPs, changes in the average size of the LPs were relatively minimal within 48 h and differences were not statistically significant. These findings suggest that all of the three kinds of LPs were highly stable in FBS for at least 48 h at 37 °C, indicating that the internal microenvironmental pH does not influence the chemical stability of LPs in FBS.

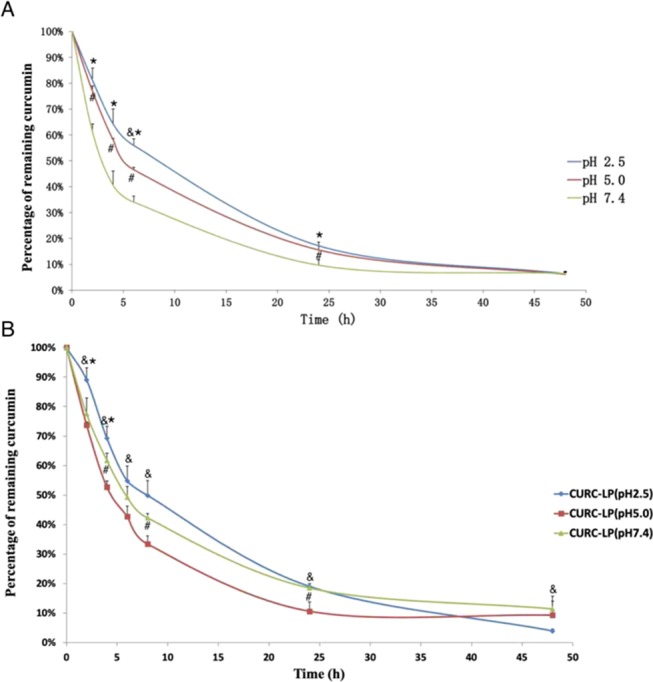

Chemical Stability of Liposomal CURC to Different External Environment pH Values

CURC has low stability under alkaline pH conditions, and its incorporation into liposomal membranes may improve its stability. However, the stability of liposomal CURC to different external environment pH values remains unclear. To understand this problem, we investigated the stability of CURC-LP (pH 7.4) to three different external environment pH values (pH 2.5, pH 5.0, and pH 7.4). As shown in Figure 5A, in all of the three pH values, the remaining percentage of CURC was lower over time. However, CURC-LP (pH 7.4) in the pH 2.5 external environment was more stable compared with pH 5.0 or pH 7.4, suggesting that CURC incorporated into LPs is still influenced by the acid and alkali of the external environment, and thus is still more stable in an acid environment.

Figure 5.

Stability of liposome-encapsulated curcumin in different external pH conditions, and stability of three kinds of liposome-encapsulated curcumin at pH 7.4. (A) In vitro stability of curcumin in CURC-LP (pH 7.4) over a 24 h period in an equal volume of FBS and PBS (pH 2.5, 5.0, and 7.4, 0.001 M) under the condition of 37 °C and 100 rpm. (B) In vitro stability of curcumin in three kinds of CURC-LPs over a 24 h period in an equal volume of FBS and PBS (pH 7.4, 0.001 M) under the condition of 37 °C and 100 rpm. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). P values <0.05 are considered statistically significant, as indicated by &, *, and #; & pH 2.5 vs. pH 5.0, * pH 2.5 vs. pH 7.4, # pH 5.0 vs. pH 7.4.

The observed differences in stability may be explained by the fact that CURC has three ionizable protons, one each from the two phenolic OH groups and the third from the enolic proton.33 The pKa values for the dissociation of the three ionizable protons in CURC have previously been determined as 7.8, 8.5, and 9.0, respectively, by Tønnesen and Karlsen in 1985. In addition, in the neutral or alkaline environment, once dissociation occurs, CURC undergoes rapid hydrolytic degradation and becomes unstable. As a lipophilic drug, CURC can be incorporated into liposomal membranes, which may protect it against hydrolytic degradation and increase its stability and has been proven in many investigations. However, when LPs are dispersed in the serum, lipophilic CURC incorporated within the LP membranes will possibly leak out at a degree that depends on the log P value of the particular compound, its aqueous solubility at physiological pH, and its affinity to plasma proteins.34 Thus, CURC that leaks out of the liposomal CURC will be affected by the pH conditions. Thus, CURC incorporated into LPs is also influenced by the acidic and alkaline conditions of the external environment. This suggests that an acidic external environment for liposomal CURC is more conducive for its storage and further applications.

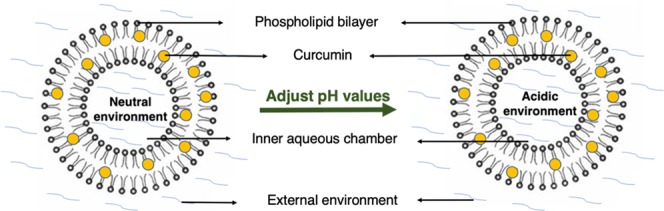

Chemical Stability of CURC-LPs in the Physiological Environment

Based on the results of the experiment described earlier, we have proven that CURC incorporated into LPs is also influenced by the acidic and alkaline conditions of the external environment. To determine whether the stability of CURC-LPs is affected by the internal microenvironmental pH in the aqueous chamber of the liposomes, we investigated the chemical stability of CURC-LPs in 50% pH 7.4 FBS. As shown in Figure 5B, in pH 7.4 FBS, the remaining percentage of CURC in the three kinds of CURC-LPs decreased over time. However, after 24 h, the remaining percentage of CURC in CURC-LP (pH 2.5) was the highest compared with CURC-LP (pH 5.0) or CURC-LP (pH 7.4) at every time point, indicating that CURC in CURC-LP (pH 2.5) is the most stable at pH 7.4, at least in the first 24 h. Using pH 2.5 as the internal microenvironment during the preparation of CURC-loaded LPs is optimal. Phospholipids are amphiphilic molecules containing a water-soluble hydrophilic head section and a lipid-soluble hydrophobic tail section. Therefore, the space in the lipid bilayer would not be absolutely anhydrous for the transport of water-soluble molecules. A certain volume of the buffer solution with the same components as the inner chamber would exist in the hydrophobic lipid bilayer after the preparation of liposome. Thus, the hydrophobic molecule incorporation into liposomal membranes still can be affected by the internal microenvironment pH. In addition, the highest stability of CURC in CURC-LP (pH 2.5) may due to the high efficiency of CURC encapsulation and better physical construction of the vesicles when compared with CURC in CURC-LP (pH 5.0) or CURC-LP (pH 7.4). Hence, creating an acidic microenvironment in the internal chamber of LPs is beneficial to the stability of liposomal CURC.

In Vitro Release Study

The drug release profile of LPs is usually examined to evaluate formulation quality and predict the effectiveness in vivo because the release profile obtained in vitro can reflect the drug’s performance in vivo. Traditionally, drug release from LPs may occur in three ways: (a) the drug molecules that are adsorbed on the surface of liposome are released via desorption once these come into contact with the release medium, (b) the encapsulated drugs in the LPs are released by diffusion through the LPs’ skeleton, or/and (c) following the degradation or disintegration of LPs. Meanwhile, the drugs in the release medium are influenced by the release medium. In this study, the PBS (pH 7.4) containing 0.1% (m/v) of the Tween-80 was used as the release medium, and we detected the existence of CURC in the release medium at specific time points for 48 h. The release profile is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

In vitro release profiles of the three kinds of CURC-LPs in PBS containing 0.1% (m/v) of the Tween-80 (pH 7.4). Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3). P values <0.05 were considered as statistically significant, as indicated by * for comparison in CURC-LP (pH 2.5) vs CURC-LP (pH 7.4).

As shown in Figure 6, the release profiles of all of the three CURC-LPs were close to a straight line, indicating that CURC-LPs exhibit a constant drug release rate. The amount of CURC was highest in the CURC-LP (pH 2.5) compared with CURC-LP (pH 5.0) or CURC-LP (pH 7.4) at every time point. These findings suggest that CURC in the CURC-LP (pH 2.5) may be most stable in the PBS (pH 7.4) containing 0.1% (m/v) of the Tween-80 compared with CURC-LP (pH 5.0) or CURC-LP (pH 7.4). This is consistent with our results above.

The water solubility of CURC can be significantly improved by loading into LPs, and its stability may also be improved by the physiological environment. In our present study, we proved that liposomal CURC is still more stable in an acidic external environment. Even after incorporation in liposomal membranes, the stability of liposomal CURC continues to be influenced by the internal microenvironmental pH in the aqueous chamber of the liposomes. Therefore, creating an acidic microenvironment in the internal chamber of LPs is beneficial to the stability of liposomal CURC. It may also provide some guidance for the optimal preparation of other liposomal pH-sensitive drug payloads.

Experimental Section

Materials

Curcumin (CURC) was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Phospholipids (soybean lecithin for injection use, with phosphatidylcholine content >70%) were purchased from Shanghai Tai-Wei Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Cholesterol was purchased from Amresco (Solon, OH). Poloxamer 188 (F68) was obtained from BASF (China) Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was obtained from HyClone (Logan, UT). All other chemical reagents used in this study were of analytical grade or better.

Preparation of Liposomes and CURC-Loaded Liposomes with Different Internal Microenvironmental pH Values

The liposomes with different internal microenvironmental pH values were prepared using the evaporation method with some modifications. First, the weighed phospholipids and cholesterol (15:1, w/w) were dissolved in absolute ethanol and served as the organic phase. Three different kinds of pH values (pH 2.5, pH 5.0, and pH 7.4) of phosphate-buffered solutions (PBS, 0.001 mol/L, the concentration of phosphate ions) containing 1% (w/w) F68 were used as the aqueous phase. Here, F68 served as a surfactant to narrow the size distribution. Using magnetic stirring, the resulting organic solution was slowly dripped into the aqueous phase at a volume ratio of 1:10, followed by evaporation at 35 °C for 30 min to remove the ethanol. The suspension was centrifuged at a high speed (16 000 rpm for 10 min), and the pellets were resuspended in PBS (pH 7.4) to provide these liposomes (LPs) with an identical external environment. Finally, liposome suspensions were obtained and designated as LP (pH 2.5), LP (pH 5.0), and LP (pH 7.4).

CURC-loaded liposomes were prepared by co-dissolving CURC, phospholipids, and cholesterol in ethanol following the same procedures as earlier described. After evaporation, the suspension was centrifuged at a low speed (3000 rpm for 5 min) to precipitate free CURC. Then, the supernatant was centrifuged at high speed (16 000 rpm for 10 min), and the pellets were resuspended in PBS (pH 7.4). Finally, the CURC-loaded liposomes with different internal microenvironmental pH values were obtained and designated as CURU-LP (pH 2.5), CURU-LP (pH 5.0), and CURU-LP (pH 7.4). For liposomes and CURC-loaded liposomes, the final concentration of the phospholipids was 15 mg/mL, cholesterol was 1 mg/mL, and CURC 0.2 mg/mL.

Characterization of LPs and CURC-LPs

The particle size, size distribution, and ζ-potential of various LPs and CURC-LPs were detected by dynamic light scattering (DLS) and electrophoretic light scattering (ELS) technologies, respectively, using the instrument of Zetasizer Nano ZS90 (Malvern Instruments Ltd., Malvern, U.K.). The particle size was assessed in terms of intensity distribution, and the polydispersity index (PDI) was used to evaluate size distribution.

The morphology of LPs was characterized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, INSPECT F, FEI, Eindhoven, The Netherlands). Before conducting SEM, one drop of the properly diluted LP suspension was placed on a clean glass sheet, followed by air-drying. Then, the samples were coated with gold.

Entrapment Efficiency of CURC

The entrapment efficiency of CURC in various CURC-LPs was determined by the high-speed centrifugation method. Briefly, various CURC-LPs were centrifuged at 16 000 rpm for 5 min. Then, the supernatant was assayed by fluorescent spectrophotometry (excitation, 458 nm; emission, 548 nm) and presented as F1, i.e., the fluorescent intensity of nonencapsulated CURC. Meanwhile, the same volume of the total CURC-LPs was measured by fluorescent spectrophotometry and presented as F0, i.e., the fluorescent intensity of total CURC. The experiments were performed in triplicate. The encapsulation efficiency (EE) of the curcumin was calculated using the following equation: EE% = (F0 – F1)/F0 × 100%.

Physical Stability of LPs

In this study, we detected the physical stability of LPs by measuring their thermodynamic stability. The freshly prepared LPs (0.15 mL) were incubated at 37 °C. At fixed time intervals, the liposome suspension was vortexed and the particle size was measured and compared to the initial size to determine their thermodynamic stability.

Chemical Stability of LPs in FBS

The freshly prepared LPs (1.4 mL) were added to each centrifuge tube and centrifuged at 16 000 rpm for 5 min. Then, the supernatant was discarded, and 1.4 mL was mixed with an equal volume of FBS and PBS (pH 7.4, 0.001 mol/L), followed by vortex blending. The resuspended liposomes in equal volumes of FBS and PBS were placed on a horizontal shaker (70 rpm, 37 ± 1 °C). At the fixed time intervals, 90 μL of the liposome suspension was aliquoted and diluted 10 times with distilled water, and the particle size was measured and compared.

Chemical Stability of Liposomal CURC to Different External Environmental pH Values

To investigate whether the chemical stability of liposomal curcumin is influenced by the external environment pH values, we detected the stability of CURC in CURC-LP (pH 7.4) under different external pH values (pH 2.5, pH 5.0, and pH 7.4). Briefly, the freshly prepared CURC-LP (pH 7.4) was diluted 10 times by PBS (pH 7.4, 0.001 mol/L), then 1 mL of the diluted solution was added to the tube and centrifuged at 16 000 rpm for 5 min. The supernatant was discarded, and 1 mL was mixed with an equal volume of FBS and PBS (pH 2.5, pH 5.0, or pH 7.4, 0.001 mol/L), followed by vortex blending. The resuspended solution was placed on a horizontal shaker (70 rpm, 37 ± 1 °C). At fixed time intervals (0, 2, 4, 6, 24, and 48 h), 10 μL of the solution was aliquoted and added to 300 μL of absolute ethanol to dissolve the liposome and extract CURC. The samples were stored at −80 °C until analysis. After all samples were collected, these were centrifuged at 12 000 rpm for 3 min, and 200 μL of the supernatant was measured by fluorescent spectrophotometry (excitation: 458 nm; emission: 548 nm). The measured fluorescent intensity at the fixed time intervals (2, 4, 6, 24, and 48 h) was compared to the fluorescent intensity at 0 h.

Chemical Stability of CURC-LPs in the Physiological Environment

The chemical stability of CURC-LPs in the physiological environment was examined in 50% FBS. Briefly, the prepared CURC-LP (pH 2.5), CURC-LP (pH 5.0), and CURC-LP (pH 7.4) were diluted 10 times with PBS (pH 2.5, pH 5.0, or pH 7.4, 0.001 mol/L), followed by the addition of 1 mL of the diluted solution and centrifugation at 16 000 rpm for 5 min. The supernatant was discarded, and 1 mL of the suspension was mixed with an equal volume of FBS and PBS (pH 7.4, 0.001 mol/L) and then vortexed. The remaining procedures were the same as described earlier.

In Vitro Release Study

The in vitro release property of CURC-LP (pH 2.5), CURC-LP (pH 5.0), and CURC-LP (pH 7.4) was investigated using the dynamic dialysis method.35 Briefly, 1 mL of CURC-LP (pH 2.5), CURC-LP (pH 5.0), or CURC-LP (pH 7.4) was added into a dialysis bag (molecular weight cutoff: 10 000D). Then, the sample-loaded dialysis bag was tightly bundled at the two ends and soaked in 6 mL of release medium [PBS containing 0.1% (m/v) of the Tween-80, pH 7.4] and placed on a horizontal shaker (70 rpm, 37 ± 1 °C). At fixed time intervals (2, 4, 6, 8, 24, and 48 h), the release medium was collected and replaced with 6 mL of fresh release medium. The collected samples were stored at −80 °C for further analysis by fluorescent spectrophotometry. After all samples were collected, these were centrifuged at 12 000 rpm for 3 min, and 200 μL of the supernatant was measured by fluorescence spectrophotometry (excitation: 458 nm; emission: 548 nm).

Statistical Analysis

All assays in this study were repeated at least thrice. A one-way ANOVA was used to analyze differences among groups. In all tables and figures, representative data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81500826).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Ghandadi M.; Sahebkar A. Curcumin: An Effective Inhibitor of Interleukin-6. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2017, 23, 921–931. 10.2174/1381612822666161006151605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komal K.; Chaudhary S.; Yadav P.; Parmanik R.; Singh M. The Therapeutic and Preventive Efficacy of Curcumin and Its Derivatives in Esophageal Cancer. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2019, 20, 1329–1337. 10.31557/APJCP.2019.20.5.1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H.; Zhong C.; Wang Q.; Chen W.; Yuan Y. Curcumin is an APE1 redox inhibitor and exhibits an antiviral activity against KSHV replication and pathogenesis. Antiviral Res. 2019, 167, 98–103. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2019.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raorane C. J.; Lee J. H.; Kim Y. G.; Rajasekharan S. K.; Garcia-Contreras R.; Lee J. Antibiofilm and Antivirulence Efficacies of Flavonoids and Curcumin Against Acinetobacter baumannii. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 990. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul S.; Mohanram K.; Kannan I. Antifungal activity of curcumin-silver nanoparticles against fluconazole-resistant clinical isolates of Candida species. Ayu 2018, 39, 182–186. 10.4103/ayu.AYU_24_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forouzanfar F.; Barreto G.; Majeed M.; Sahebkar A. Modulatory effects of curcumin on heat shock proteins in cancer: A promising therapeutic approach. Biofactors 2019, 45, 631–640. 10.1002/biof.1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howells L. M.; Iwuji C. O. O.; Irving G. R. B.; Barber S.; Walter H.; Sidat Z.; Griffin-Teall N.; Singh R.; Foreman N.; Patel S. R.; Morgan B.; Steward W. P.; Gescher A.; Thomas A. L.; Brown K. Curcumin Combined with FOLFOX Chemotherapy Is Safe and Tolerable in Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer in a Randomized Phase IIa Trial. J. Nutr. 2019, 149, 1133–1139. 10.1093/jn/nxz029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arozal W.; Ramadanty W. T.; Louisa M.; Satyana R. P. U.; Hartono G.; Fatrin S.; Purbadi S.; Estuningtyas A.; Instiaty I. Pharmacokinetic Profile of Curcumin and Nanocurcumin in Plasma, Ovary, and Other Tissues. Drug Res. 2019, 69, 559–564. 10.1055/a-0863-4355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirzaei H.; Shakeri A.; Rashidi B.; Jalili A.; Banikazemi Z.; Sahebkar A. Phytosomal curcumin: A review of pharmacokinetic, experimental and clinical studies. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 85, 102–112. 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.11.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand P.; Kunnumakkara A. B.; Newman R. A.; Aggarwal B. B. Bioavailability of curcumin: problems and promises. Mol. Pharm. 2007, 4, 807–818. 10.1021/mp700113r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues F. C.; Anil Kumar N. V.; Thakur G. Developments in the anticancer activity of structurally modified curcumin: An up-to-date review. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 177, 76–104. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.04.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saheb M.; Fereydouni N.; Nemati S.; Barreto G. E.; Johnston T. P.; Sahebkar A. Chitosan-based delivery systems for curcumin: A review of pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic aspects. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 12325–12340. 10.1002/jcp.28024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan S.; Sun Y.; Qi X.; Tan F. Improved bioavailability of poorly water-soluble drug curcumin in cellulose acetate solid dispersion. AAPS PharmSciTech 2012, 13, 159–166. 10.1208/s12249-011-9732-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei X.; Senanayake T. H.; Bohling A.; Vinogradov S. V. Targeted nanogel conjugate for improved stability and cellular permeability of curcumin: synthesis, pharmacokinetics, and tumor growth inhibition. Mol. Pharm. 2014, 11, 3112–3122. 10.1021/mp500290f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M.; Du C.; Guo N.; Teng Y.; Meng X.; Sun H.; Li S.; Yu P.; Galons H. Composition design and medical application of liposomes. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 164, 640–653. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zununi Vahed S.; Salehi R.; Davaran S.; Sharifi S. Liposome-based drug co-delivery systems in cancer cells. Mater. Sci. Eng., C 2017, 71, 1327–1341. 10.1016/j.msec.2016.11.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosova A. S.; Koloskova O. O.; Nikonova A. A.; Simonova V. A.; Smirnov V. V.; Kudlay D.; Khaitov M. R. Diversity of PEGylation methods of liposomes and their influence on RNA delivery. MedChemComm 2019, 10, 369–377. 10.1039/C8MD00515J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardania H.; Tarvirdipour S.; Dorkoosh F. Liposome-targeted delivery for highly potent drugs. Artif. Cells, Nanomed., Biotechnol. 2017, 45, 1478–1489. 10.1080/21691401.2017.1290647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwendener R. A. Liposomes as vaccine delivery systems: a review of the recent advances. Ther. Adv. Vaccines 2014, 2, 159–182. 10.1177/2051013614541440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seleci M.; Ag Seleci D.; Scheper T.; Stahl F. Theranostic Liposome-Nanoparticle Hybrids for Drug Delivery and Bioimaging. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1415 10.3390/ijms18071415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daeihamed M.; Dadashzadeh S.; Haeri A.; Akhlaghi M. F. Potential of Liposomes for Enhancement of Oral Drug Absorption. Curr. Drug Delivery 2017, 14, 289–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Signorell R. D.; Luciani P.; Brambilla D.; Leroux J. C. Pharmacokinetics of lipid-drug conjugates loaded into liposomes. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2018, 128, 188–199. 10.1016/j.ejpb.2018.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tretiakova D.; Onishchenko N.; Boldyrev I.; Mikhalyov I.; Tuzikov A.; Bovin N.; Evtushenko E.; Vodovozova E. Influence of stabilizing components on the integrity of antitumor liposomes loaded with lipophilic prodrug in the bilayer. Colloids Surf., B 2018, 166, 45–53. 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2018.02.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ipar V. S.; Dsouza A.; Devarajan P. V. Enhancing Curcumin Oral Bioavailability Through Nanoformulations. Eur. J. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2019, 44, 459–480. 10.1007/s13318-019-00545-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matloob A. H.; Mourtas S.; Klepetsanis P.; Antimisiaris S. G. Increasing the stability of curcumin in serum with liposomes or hybrid drug-in-cyclodextrin-in-liposome systems: a comparative study. Int. J. Pharm. 2014, 476, 108–115. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2014.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolter M.; Wittmann M.; Koll-Weber M.; Suss R. The suitability of liposomes for the delivery of hydrophobic drugs - A case study with curcumin. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2019, 140, 20–28. 10.1016/j.ejpb.2019.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R.; Deng L.; Cai Z.; Zhang S.; Wang K.; Li L.; Ding S.; Zhou C. Liposomes coated with thiolated chitosan as drug carriers of curcumin. Mater. Sci. Eng., C 2017, 80, 156–164. 10.1016/j.msec.2017.05.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sercombe L.; Veerati T.; Moheimani F.; Wu S. Y.; Sood A. K.; Hua S. Advances and Challenges of Liposome Assisted Drug Delivery. Front. Pharmacol. 2015, 6, 286. 10.3389/fphar.2015.00286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed K. S.; Hussein S. A.; Ali A. H.; Korma S. A.; Lipeng Q.; Jinghua C. Liposome: composition, characterisation, preparation, and recent innovation in clinical applications. J. Drug Targeting 2019, 27, 742–761. 10.1080/1061186X.2018.1527337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karewicz A.; Bielska D.; Gzyl-Malcher B.; Kepczynski M.; Lach R.; Nowakowska M. Interaction of curcumin with lipid monolayers and liposomal bilayers. Colloids Surf., B 2011, 88, 231–239. 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2011.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng T.; Wei Y.; Lee R. J.; Zhao L. Liposomal curcumin and its application in cancer. Int. J. Nanomed. 2017, 12, 6027–6044. 10.2147/IJN.S132434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Q.; Zhang Z. R.; Gong T.; Chen G. Q.; Sun X. A rapid-acting, long-acting insulin formulation based on a phospholipid complex loaded PHBHHx nanoparticles. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 1583–1588. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.10.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tønnesen H. H.; Masson M.; Loftsson T. Studies of curcumin and curcuminoids. XXVII. Cyclodextrin complexation: solubility, chemical and photochemical stability. Int. J. Pharm. 2002, 244, 127–135. 10.1016/S0378-5173(02)00323-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon D.; Gupta N.; Mulla N. S.; Shukla S.; Guerrero Y. A.; Gupta V. Role of In Vitro Release Methods in Liposomal Formulation Development: Challenges and Regulatory Perspective. AAPS J. 2017, 19, 1669–1681. 10.1208/s12248-017-0142-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priyadarsini K. I. Photophysics, photochemistry and photobiology of curcumin: Studies from organic solutions, bio-mimetics and living cells. J. Photochem. Photobiol., C 2009, 10, 81–95. 10.1016/j.jphotochemrev.2009.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]