Abstract

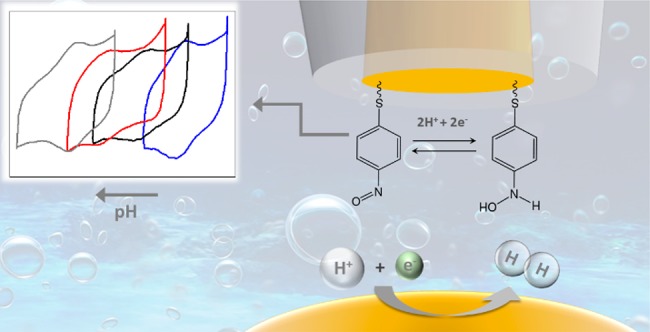

Probing pH gradients during electrochemical reactions is important to better understand reaction mechanisms and to separate the influence of pH and pH gradients from intrinsic electrolyte effects. Here, we develop a pH sensor to measure pH changes in the diffusion layer during hydrogen evolution. The probe was synthesized by functionalizing a gold ultramicroelectrode with a self-assembled monolayer of 4-nitrothiophenol (4-NTP) and further converting it to form a hydroxylaminothiophenol (4-HATP)/4-nitrosothiophenol (4-NSTP) redox couple. The pH sensing is realized by recording the tip cyclic voltammetry and monitoring the Nernstian shift of the midpeak potential. We employ a capacitive approach technique in our home-built Scanning Electrochemical Microscope (SECM) setup in which an AC potential is applied to the sample and the capacitive current generated at the tip is recorded as a function of distance. This method allows for an approach of the tip to the electrode that is electrolyte-free and consequently also mediator-free. Hydrogen evolution on gold in a neutral electrolyte was studied as a model system. The pH was measured with the probe at a constant distance from the electrode (ca. 75 μm), while the electrode potential was varied in time. In the nonbuffered electrolyte used (0.1 M Li2SO4), even at relatively low current densities, a pH difference of three units is measured between the location of the probe and the bulk electrolyte. The time scale of the diffusion layer transient is captured, due to the high time resolution that can be achieved with this probe. The sensor has high sensitivity, measuring differences of more than 8 pH units with a resolution better than 0.1 pH unit.

The pH affects chemical reactions in a wide variety of systems and pH effects have been studied in the fields of biology,1,2 medicine,3,4 corrosion,5,6 and electrocatalysis,7 among others. For example, during electrochemical reactions that consume or produce either protons or hydroxyl ions, a pH gradient is built up in the diffusion layer. The proton concentration at the electrode–electrolyte interface is known to influence the kinetics and selectivity of various electrochemical reactions such as hydrogen evolution,8 CO2 reduction,9,10 nitrate reduction,11 and oxygen evolution.12 Measuring the pH near the surface allows to better model these electrocatalytic processes and to understand their mechanism under different reaction conditions and in different electrolytes. In order to probe the diffusion layer, the spatial resolution of the conventional pH glass electrode and other bulk techniques using optical13 or colorimetric14 sensors is not high enough. Instead, local measurements of pH at the micro- and nanoscale can be achieved with Scanning Electrochemical Microscopy (SECM) where miniaturized electrodes are used to probe the local properties of an interface.15 High spatial and temporal resolution of these measurements can be achieved, which mainly depend on the kind of probe used and the electrochemical signal monitored. Spectroscopic pH measurements at the microscale have also been reported.16−18 However, such measurements do not probe the local proton concentration directly, can only be used for specific electrodes and electrocatalytic reactions, and do not provide spatial resolution. Fluorescence microscopy19−21 has also been used to map interfacial pH. Although pH maps can be obtained relatively quickly, the need of adding a fluorophore to the electrolyte is a drawback as it may affect the electrochemical process being studied. Based on the discussion presented here, SECM should be a more suitable technique to measure the interfacial pH during electrocatalytic reactions.

Different probes have been proposed for conducting local pH measurements with SECM. Various transition metal oxides show a super Nernstian open circuit potential (OCP) shift with pH and have been employed as potentiometric pH sensors. Iridium oxide (IrOx) is the most commonly used22 and several synthesis methods have been reported such as nanoparticles electrodeposition,23 anodic growth,24 and sol–gel synthesis.25 The sensing response relies on the porosity of the oxide layer; dense oxide films have a slow response to pH changes, while porous layers show a fast response, but with a significant OCP drift.26 Besides drift, another drawback of these probes comes from the adsorption of species on the sensor surface (contaminants, ions, reaction products) that can lead to a convoluted OCP response.27 These limitations can strongly influence how precisely these IrOx pH sensors capture the local pH gradient during electrochemical reactions. In addition, oxide dissolution can compromise the use of these probes in highly acidic or alkaline media.28 To overcome these limitations, polymer-based potentiometric sensors29 have been proposed, such as polyaniline-coated Au electrodes,30 and carbon electrodes modified with poly(1-naphthylamine)31 or polydopamine.32 However, many of these polymer films strongly interact with alkali metal cations which may lead to a shift in the OCP.33 In addition, the time response is reported to strongly depend on the quality of the electropolymerization and film thickness.

Other techniques have also been used to probe the pH near the surface. Ryu et al. used the pH-sensitive reaction of H2 with cis-2-butene-1,4-diol to probe the interfacial pH during concurrent hydrogen oxidation.34 Even though significant effects were observed as a function of buffer capacity and current density, the impact of the addition of cis-2-butene-1,4-diol to the electrolyte on the electrocatalysis cannot be determined and might limit the use of this technique to probe other reactions. Measurements of local pH have also been performed using a Rotating Ring-Disk Electrode (RRDE).35,36 However, this method is limited in terms of the electrode materials, reactions to be analyzed, and lack spatial resolution. Voltammetric pH sensors have also been proposed and are interesting due to their fast response and operation in large pH ranges.37−40 Boltz and co-workers, for instance, used the voltammetry of platinum nanoelectrodes to monitor the pH above a gas diffusion electrode during oxygen reduction.41 However, platinum can only be used to probe reactions that do not generate species that strongly interact with the surface, affecting the voltammetry. Michalak et al. developed nano pH sensors based on the cyclic voltammetry of syringaldazine polymer films attached to carbon substrates.42 Even though the sensor works in a large pH range, the stability of polymer films, in general, is still concerning, as film detachment can hinder the pH response.

In this work, we present a pH sensor based on the irreversible self-assembly of 4-nitrothiophenol on a gold ultramicroelectrode (Au-UME). After conversion, the hydroxylaminothiophenol/4-nitrosothiophenol redox couple is formed and its midpeak potential shows a Nernstian shift of 57 mV/pH. Using hydrogen evolution as a model system, we can perform pH measurements in the diffusion layer with high reproducibility. Because of the sensitivity of the functionalized tip and to avoid possible side effects from redox-active mediators, we also introduce an ex situ capacitive approach method to control the absolute tip-to-sample distance.43 In contrast to potentiometric pH sensors, our probe provides high time resolution and stable response. In addition, the pH sensitivity is not affected by electrolyte species or reaction products, which allows for application in a wide variety of systems (electrocatalytic or not).

Experimental Section

pH Sensor Fabrication and Characterization

Gold ultramicroelectrodes (Au-UMEs) were fabricated by sealing a gold wire (50 μm diameter, H. Drijfhout en Zoon’s Edelmetaalbedrijven B.V.) in a glass capillary (0.4 mm i.d., Drummond Scientific Co.) and exposing a cross section by grinding the electrode with a silicon carbide paper (grit size 600, MaTeck). The surface was prepared by polishing with a 1, 0.25, and 0.05 μm diamond suspension (MetaDi, Buehler) for 2 min. In between each polishing step the electrode was sonicated (Bandelin Sonorex RK 52H) in ultrapure water (>18.2 MΩ cm, Millipore Milli-Q) for 5 min and, after the last step, 5 min in ethanol followed by 15 min in water. After surface preparation, the electrode was characterized by cyclic voltammetry in 0.1 M H2SO4, recorded in a one compartment cell (20 mL) using a gold wire (0.5 mm diameter, MaTeck, 99.9%) as counter electrode and a Ag/AgCl (LowProfile, Pine Research Instrumentation) reference electrode. The electrochemical measurements reported in this work were performed using a Bio-Logic 2-channel potentiostat/galvanostat/EIS (SP-300). The Au-UMEs were modified with 4-nitrothiophenol (4-NTP, Merck, 80%) by immersion in a 1 mM 4-NTP/ethanol solution. After 20 min, the electrode was thoroughly rinsed with ethanol and ultrapure water in order to remove weakly adsorbed species. The functionalized electrode was transferred back to a 0.1 M H2SO4 solution in order to convert the organic molecule by polarization from 0.1 to −0.25 V versus Ag/AgCl (100 mV s–1). Calibration of the pH sensor was performed by cyclic voltammetry in 0.1 M Li2SO4 (Alfa Aesar, anhydrous, 99.99% metal basis) solutions saturated with argon or hydrogen at various pH. The pH was adjusted by the addition of appropriate amounts of 1 M H2SO4 (Merck, Suprapur, 96%) or 1 M LiOH (Merck, monohydrate, 99.995% trace metals basis). The pH of the calibration solutions was determined with a glass-electrode pH meter (Lab 855, SI Analytics) calibrated with standard buffer solutions (Radiometer Analytical).

SECM Measurements

SECM experiments were performed in a home-built system equipped with x-y-z stepper motors (C-863 Mercury, PI) and piezo positioners (E-665, PI). The sample was a gold disc (0.5 mm thick, MaTeck, 99.995%) cleaned and polished with diamond suspension using the protocol described elsewhere.44 A copper plate (0.5 mm thick, MaTeck) is used to make the electrical contact to the sample. A schematic representation of the SECM setup and a more detailed description can be found in Figure S1 in the Supporting Information.

The glass SECM cell and gas bubblers were cleaned by immersion in potassium permanganate solution for 24 h (1 g L–1 KMnO4 dissolved in 0.5 M H2SO4), followed by immersion in dilute piranha solution in order to remove residues of manganese oxide and permanganate anions. The glassware was further cleaned by boiling at least five times in ultrapure water.

The mediator-free approach of the modified Au-UME to the gold working electrode was performed in air by applying a 10 kHz AC voltage with an amplitude of 4 Vpp (1.41 VRMS) to the sample using a function generator (33210A, Keysight). The gold ultramicroelectrode was connected to a low noise current preamplifier (SR570, Stanford Research) operated at high-bandwidth with a gain of 2 × 108 V A–1. The capacitive tip current was obtained using a virtual lock-in amplifier (LabView).

To measure the pH during hydrogen evolution, the SECM electrochemical cell was filled with 5 mL of 0.1 M Li2SO4 brought to pH 3.2 by the addition of an adequate amount of 1 M H2SO4. The experiment was performed in a six-electrode configuration, where the tip and the sample were controlled by two distinct potentiostat channels. Two gold wires and two Ag/AgCl electrodes were used as counter and reference electrodes, respectively. Argon was purged through and above the solution throughout the whole experiment in order to avoid oxygen diffusion into the electrolyte. Measurements were performed with the pH sensor at a constant distance from the surface and the tip voltammetry was constantly recorded at a scan rate of 200 mV s–1 (5 s per cycle) while the sample potential was varied. The midpeak potential for each cycle was obtained by fitting the tip voltammetry (see SI) and converted to pH using the calibration curve.

Results and Discussion

Functionalized Gold pH Sensor

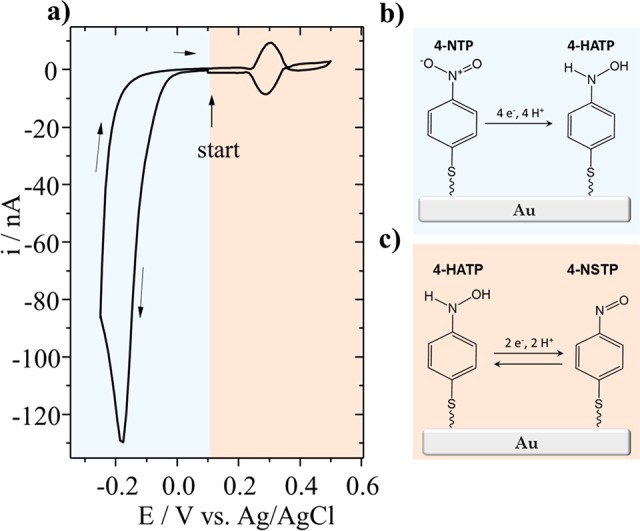

It has been previously shown how important the surface preparation and cleanliness of UMEs is for their use in electrocatalysis.45 Au-UMEs were characterized in 0.1 M H2SO4 before functionalization (see Figure S2 in SI) in order to ensure the glass is efficiently sealing the gold wire and that the surface is clean. Functionalization was performed by immersing the probe in a solution containing 4-nitrothiophenol (4-NTP). The molecules form a self-assembled monolayer at the gold surface, binding through the thiol anchor group. The free nitro group is then partially reduced electrochemically into a hydroxyl amino group by cycling the tip from 0.1 to −0.25 V versus Ag/AgCl in 0.1 M H2SO4. The voltammogram (CV) of the conversion and a schematic representation of the species formed are shown in Figure 1a and b, respectively. Hydroxylaminothiophenol (4-HATP) is formed through the transfer of four protons and four electrons and at positive potentials 4-HATP is reversibly oxidized to 4-nitrosothiophenol (4-NSTP) through the transfer of two protons and two electrons (see Figure 1c). Thus, the midpeak potential of the 4-HATP/4-NSTP redox couple is expected to show a Nernstian shift with pH.46

Figure 1.

(a) Voltammetry (0.1 M H2SO4, 100 mV s–1) and schematic representation of the conversion of (b) 4-nitrothiophenol (4-NTP) to 4-hydroxiaminothiophenol (4-HATP), and (c) the two proton–two electron transfer reaction of the redox couple 4-HATP/4-NSTP.

The electrochemical characterization of the reversible redox couple 4-HATP/4-NSTP in Figure 2a shows that the tip voltammetry is very stable over the 30 cycles performed. It is important to point out that for successful functionalization of the Au-UME the potential of the tip must be carefully controlled. It has been previously shown by Touzalin et al. that at potentials lower than −0.25 V vs Ag/AgCl (pH = 1) 4-NTP and 4-HATP are fully irreversibly reduced to 4-aminothiophenol (4-ATP).47 At potentials higher than 0.6 V vs Ag/AgCl the monolayer is destabilized leading to a decrease in the 4-HATP/4-NSTP signal intensity (although the exact mechanism that leads to destabilization is not yet clear).

Figure 2.

(a) Characterization of the electroactive redox couple 4-HATP/4-NATP in 0.1 M H2SO4 at 200 mV s–1, and (b) calibration of the functionalized Au-UME in 0.1 M Li2SO4 solutions adjusted to different pH and saturated with argon or hydrogen.

In order to calibrate the pH sensor, the tip voltammetry was recorded in argon saturated solutions of various pH values (see Figure S3 in the SI). The potential of the anodic peak as a function of pH was used to construct the calibration curves depicted in Figure 2b. A linear fit of the data provides the following relationship: pH = (0.341 – Epeak)/0.057, with an R2 value of 0.99. The midpeak potential shows a Nernstian behavior with a shift of 57 mV per pH unit. As the tip will be used to probe pH changes during hydrogen evolution, it was also calibrated in hydrogen atmosphere. As can be seen in Figure 2b, the presence of hydrogen does not affect the pH response. Even though the calibration curve shown in Figure 2b does not include pH 7, other calibration curves were made where pH 7 was included and different from the work of Cobb et al.48 on quinone-based pH electrodes, no significant deviation of the Nernstian response was found. The latter is probably related to the different interaction the quinone has with the substrate in comparison to the 4-nitrothiophenol self-assembled monolayer. In addition, 4-nitrothiophenol is only partially converted to 4-hydroxiaminothiophenol, and according to Cobb’s work, the lower the coverage of the surface, the lower the deviations.

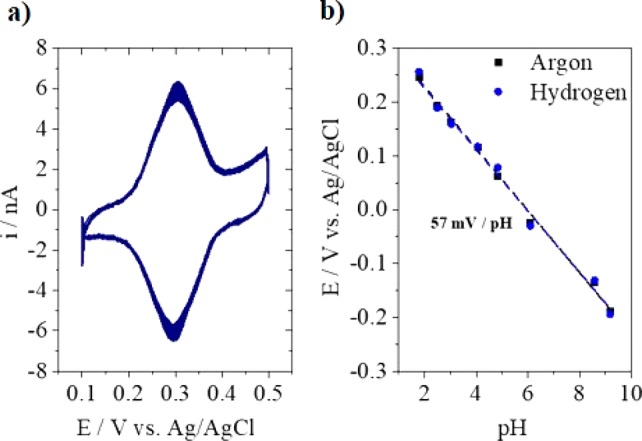

Mediator-Free Approach

Commonly used SECM approach techniques need a mediator or a diffusion limited reaction taking place at the tip in order to determine the tip-to-sample distance.49 However, these methods are not ideal, because they can contaminate the electrocatalytic system and destabilize the self-assembled monolayer. Furthermore, it has been shown that commonly made assumptions about the exact tip geometry lead to significant errors in the calculated tip-to-sample distance.50 In principle, AC-SECM51,52 could be employed, however, it is not known how stable the self-assembled monolayer is at high frequencies. Therefore, we have applied an electrolyte-free approach method that allows determining the absolute tip-to-surface distance without destabilizing the 4-NTP/4-HATP/4-NSTP monolayer. This ex situ method employs the capacitance between tip and sample and was recently introduced by De Voogd et al. as a preapproach for STM setups.43

To enable the determination of the tip–sample capacitance in air, an AC potential (10 kHz, 1.41 VRMS) is applied to the sample and the resulting tip current is followed with a preamplifier. The out-of-phase (Y) component of the tip current is determined using a lock-in amplifier. Figure 3a shows a schematic representation of the approach configuration. The capacitance can be calculated via

| 1 |

where G is the preamplifier gain and f and V are the frequency and amplitude of the reference (sample) signal, respectively. The tip and sample can be described as a parallel plate capacitor, of which the capacitance is

| 2 |

where ε0 is the permittivity of air, A is the area (of the tip), and d is the tip-to-sample distance. The total measured capacitance also contains contributions that are inherent to the setup, for example, due to the tip connection far away from the sample and the connections used.43 These contributions can be well approximated with a linear function of distance d. Ctot can thus be fitted with the following equation:

| 3 |

where Z is the position of the stepper motor varied during the approach, d0 is the absolute surface position, and b and c are scaling parameters for the additional contributions. Figure 3b shows a measured approach curve together with its fit, demonstrating clearly that the measured capacitance at short distances is dominated by Cpar. This enables us to approach the surface to a distance well below the tip diameter (here, 10–30 μm with a 50 μm diameter tip) in a safe and reproducible way. The fitting parameter d0 allows to obtain the absolute tip-to-surface distance. It is important to point out that the shape of the approach curve is not affected by the probe RG (radius of the insulating layer divided by the radius of the active layer), which means that it can be employed in any SECM setup. It should be noted that, due to humidity, the measured permittivity (ε) differs from the permittivity of dry air (ε0). In a Kelvin probe approach, this is known to significantly change the approach curve.53 However, as seen from eq 3, it is clear that for the capacitive approach only the absolute capacitance changes as a function of ε, while the shape of the approach curve remains the same. Finally, we have successfully tested this approach technique with electrodes of different geometries and dimensions. With the appropriate electronics, the capacitive approach can also be used for significantly smaller tips than presented here. However, one should realize that, as the shape of the approach curve does not depend on the tip diameter, without detailed tip characterization the accuracy of this method is in the range of 3–5 μm.

Figure 3.

(a) Capacitive approach configuration and (b) approach curve obtained (blue circles) with its fit to eq 3 (red line).

pH Measurements

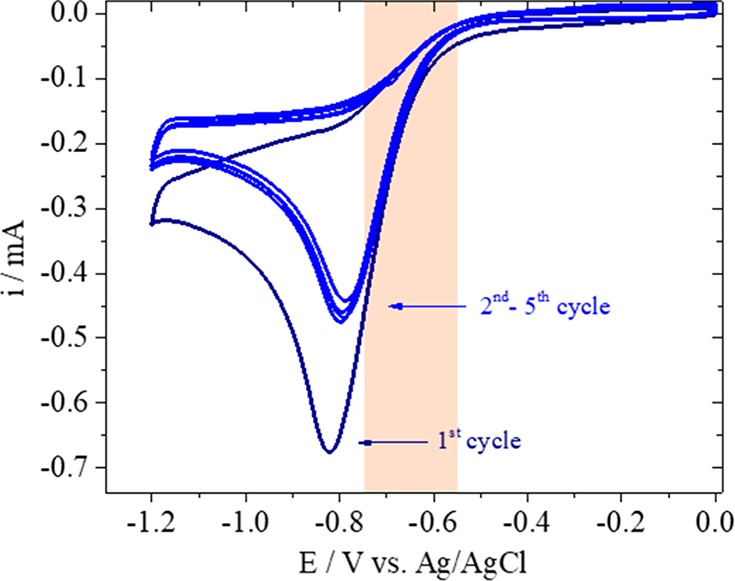

The functionalized gold pH sensor was used to study hydrogen evolution (HER) on gold (0.1 M Li2SO4, pH = 3.2) as a model system. Before the pH measurements were performed, the CV of HER was recorded at the gold substrate, which is shown in Figure 4. The cathodic current observed is due to the reduction of protons (2H+ + 2e– → H2). The reaction rate is initially governed by kinetics and below −0.8 V versus Ag/AgCl, the reaction becomes diffusion limited. As protons are consumed at the interface and the diffusion layer thickness increases, a pH gradient is built up. This can be observed in the CV by the decrease of the cathodic current from the first to the subsequent cycles due to proton depletion. However, quantification of the local pH is not possible based on the CV alone. At potentials more negative than −1.2 V versus Ag/AgCl and bulk pH, mainly the reduction of water would take place (2H2O + 2e– → H2 + 2OH–). The SECM pH measurements were performed in the potential range highlighted in the CV, in which only proton reduction is taking place.

Figure 4.

Cyclic voltammogram of hydrogen evolution taking place at the gold sample in 0.1 M Li2SO4 (pH = 3.2) recorded at 100 mV s–1.

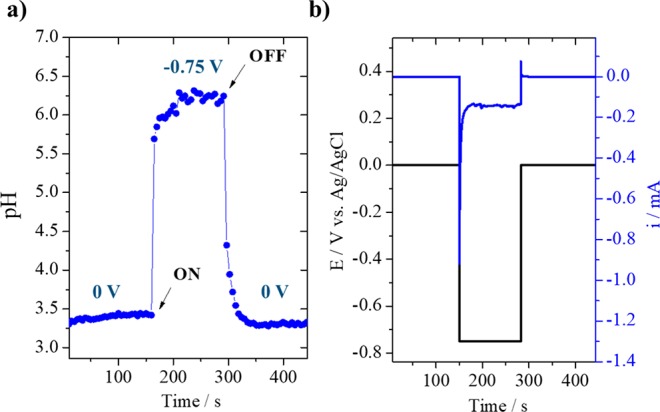

SECM pH measurements were carried out with the functionalized Au-UME placed at fixed distance, 75 ± 2 μm from the surface. Hydrogen evolution was turned “on” and “off” at the gold sample while the tip voltammetry was recorded at a scan rate of 200 mV s–1. An example of the shift observed in the tip voltammetry can be found in Figure S4 in the SI. The tip CVs were fitted and the potential of the anodic peak determined as a function of time (see Figure S5). The calibration curve shown in Figure 2 was used to convert the tip peak potentials to pH. Details on the data fitting can be found in the Supporting Information. Results depicted in Figure 5 show the pH changes taking place when HER is turned “on” and “off” at the sample at −0.75 V versus Ag/AgCl. Each data point corresponds to the midpeak potential extracted from each Au-UME CV. At −0.75 V versus Ag/AgCl, protons are being consumed at the gold working electrode and it can be seen that the pH has an initial fast increase of more than two units and takes 50 s to reach a stable value. By observing the sample chronoamperometry curve (Figure 5b), it can be seen that this is also the time needed for the current to reach diffusion limitation due to an initially fast increase in local pH and diffusion layer thickness. At −0.75 V, the maximum pH value of 6.3 was reached. This strong pH increase can be explained by the fact that the electrolyte is not buffered. After 150 s, HER is turned “off” and the near-surface pH returns to the bulk pH value. Similar measurements were previously performed with an IrOx sensor.54 Comparing our results with the data presented in Figure 8 of ref (54), it can be seen that our probe captures the time scale of the pH changes during HER more precisely, allowing for a larger number of data points to be obtained in time, only dependent on the scan rate at which the tip voltammetry is recorded. In addition, our pH sensor is more stable and the response does not drift in time, which is a common drawback of potentiometric sensors such as IrOx.

Figure 5.

(a) pH measurement during hydrogen evolution in 0.1 M Li2SO4 (pH = 3.2) with the sample at −0.75 V vs Ag/AgCl; (b) chronoamperometry recorded at the sample.

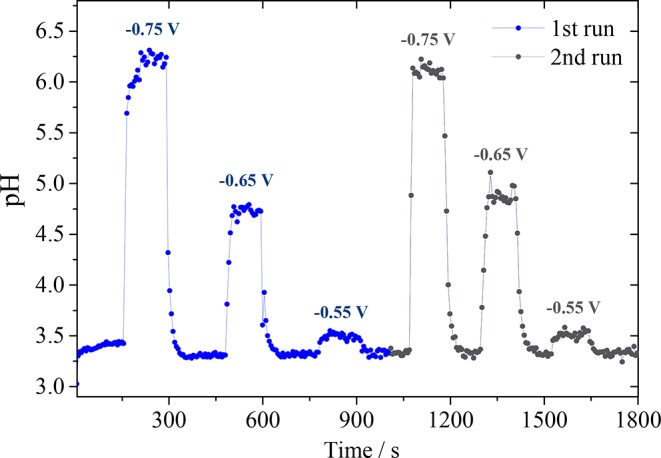

Measurements were also performed at less negative sample potentials that, due to the slower consumption of protons, should lead to lower pH values than obtained at −0.75 V versus Ag/AgCl. As depicted in Figure 6 when −0.65 V versus Ag/AgCl is applied to the sample, the pH reaches 4.75, and when HER is carried out at −0.55 V versus Ag/AgCl, only a small increase of less than one pH unit is observed. The corresponding sample chronoamperometry can be seen in Figure S6 in the SI. In order to ensure reproducibility of the pH response, a second measurement was performed applying the same negative potentials (black curve in Figure 6). It can be seen that the same pH values were reached for the same potentials. This also shows how thermal drift does not compromise the measurements.

Figure 6.

pH measurements in the diffusion layer during hydrogen evolution in 0.1 M Li2SO4 (pH = 3.2) at different sample potentials. The measurement was performed in duplicate.

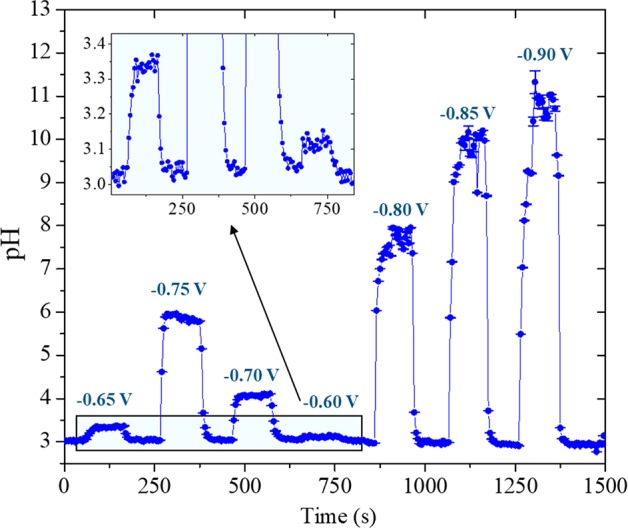

Another set of HER experiments was performed where the sample potential was changed in smaller steps, to demonstrate the sensitivity of the pH probe. The results can be seen in Figure 7, where the sample potential was varied from −0.6 to −0.9 V vs Ag/AgCl in steps of 50 mV. The electrolyte bulk pH was 3 and a gradual increase in pH can be observed as a function of sample potential, irrespective of the fact that the potentials are applied in a random order. The sample chronoamperometry recorded during the experiment can be found in Figure S7 in the SI. The inset in Figure 7 shows the remarkable sensitivity of our pH probe, as differences of 0.1 and 0.35 pH units were recorded when the sample potential was −0.6 and −0.65 V versus Ag/AgCl, respectively. In addition, measurements at more negative sample potentials show the large pH range at which the probe can be employed. Note that the absolute pH values cannot directly be compared between this measurement and the one shown in Figure 6 as different spots of the polycrystalline gold sample have distinct reactivities toward HER and the starting bulk pH is not the same.

Figure 7.

pH measurements in the diffusion layer during hydrogen evolution in 0.1 M Li2SO4 (pH = 3) performed in a wider potential range. The inset shows the small pH differences recorded when the sample potential was −0.65 and −0.60 V vs Ag/AgCl.

It is important to point out that during the measurements, the potential window of the tip voltammetry must be adjusted due to the pH changes happening locally. Not only the 4-HATP/4-NSTP midpeak potential shifts with pH but also the potential at which the unwanted tip reactions take place, that is, 4-ATP formation and destabilization of the self-assembled monolayer. Therefore, the 4-HATP/4-NSTP peak intensity would decrease drastically if the potential limits are not adjusted accordingly. In addition, the time resolution of the measurement can be adjusted according to the time scale of the reaction being studied (test CVs were recorded until up to 600 mV s–1 and the tip voltammetry was still stable).

Conclusions

In this work, we have successfully developed a pH sensor based on the self-assembly of 4-nitrothiphenol on gold ultramicroelectrodes. The probe voltammetry shows a Nernstian behavior with 57 mV/pH shift, which is not affected by the electrolyte composition. To ensure cleanliness and avoid destabilization of the probe, we employ a mediator- and electrolyte-free capacitive approach in order to determine the absolute tip-to-sample distance. We have measured the pH during hydrogen evolution with the tip placed at a constant distance, 75 μm from the surface. Results show that our pH probe provides superior time resolution compared to previously reported potentiometric IrOx pH sensors, allowing to capture the dynamics of proton diffusion during hydrogen evolution. A gold UME of 50 μm diameter was used in this work, but the functionalization with 4-NTP can also be carried out using smaller gold UMEs for further spatially resolved measurements. This would also allow for measurements with the probe positioned closer to the surface. Summarizing, we presented a highly sensitive and selective miniature pH probe that can be applied to a wide variety of systems, changing for example the gas atmosphere, electrolyte composition, and substrate. This work provides the means for more precise determination of the spatially resolved diffusion layer pH under different reactions. Consequently, it will help to better understand and model electrocatalytic reactions.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the European Commission under Contract 722614 (Innovative training network Elcorel).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.analchem.9b04952.

Details on the SECM setup, blank voltammetry of the gold ultramicroelectrode, tip calibration voltammetry, data analysis, and sample chronoamperometry (PDF)

Author Contributions

‡ These authors contributed equally. The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Munteanu R.-E.; Stǎnicǎ L.; Gheorghiu M.; Gáspár S. Measurement of the Extracellular pH of Adherently Growing Mammalian Cells with High Spatial Resolution Using a Voltammetric pH Microsensor. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90 (11), 6899–6905. 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b01124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi V. S.; Sheet P. S.; Cullin N.; Kreth J.; Koley D. Real-Time Metabolic Interactions between Two Bacterial Species Using a Carbon-Based pH Microsensor as a Scanning Electrochemical Microscopy Probe. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89 (20), 11044–11052. 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b03050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J.; Groisman E. A. Acidic pH Sensing in the Bacterial Cytoplasm Is Required for Salmonella Virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 2016, 101 (6), 1024–1038. 10.1111/mmi.13439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q.; Liu X.; Chen J.; Zeng J.; Cheng Z.; Liu Z. A Self-Assembled Albumin-Based Nanoprobe for In Vivo Ratiometric Photoacoustic pH Imaging. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27 (43), 6820–6827. 10.1002/adma.201503194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filotás D.; Fernández-Pérez B. M.; Izquierdo J.; Kiss A.; Nagy L.; Nagy G.; Souto R. M. Improved Potentiometric SECM Imaging of Galvanic Corrosion Reactions. Corros. Sci. 2017, 129, 136–145. 10.1016/j.corsci.2017.10.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R.; Zhang M.; Meng Q.; Yuan B.; Zhu Y.; Li L.; Wang C. Oscillations of pH at the Fe|H2SO4 Interface during Anodic Dissolution. Electrochem. Commun. 2017, 82, 103–106. 10.1016/j.elecom.2017.08.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koper M. T. M. Theory of Multiple Proton-Electron Transfer Reactions and Its Implications for Electrocatalysis. Chem. Sci. 2013, 4 (7), 2710–2723. 10.1039/c3sc50205h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J.; Sheng W.; Zhuang Z.; Xu B.; Yan Y. Universal Dependence of Hydrogen Oxidation and Evolution Reaction Activity of Platinum-Group Metals on pH and Hydrogen Binding Energy. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2 (3), e1501602 10.1126/sciadv.1501602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ooka H.; Figueiredo M. C.; Koper M. T. M. Competition between Hydrogen Evolution and Carbon Dioxide Reduction on Copper Electrodes in Mildly Acidic Media. Langmuir 2017, 33, 9307. 10.1021/acs.langmuir.7b00696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kas R.; Kortlever R.; Yılmaz H.; Koper M. T. M.; Mul G. Manipulating the Hydrocarbon Selectivity of Copper Nanoparticles in CO2 Electroreduction by Process Conditions. ChemElectroChem 2015, 2 (3), 354–358. 10.1002/celc.201402373. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Gallent E.; Figueiredo M. C.; Katsounaros I.; Koper M. T. M. Electrocatalytic Reduction of Nitrate on Copper Single Crystals in Acidic and Alkaline Solutions. Electrochim. Acta 2017, 227, 77–84. 10.1016/j.electacta.2016.12.147. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Morales O.; Ferrus-Suspedra D.; Koper M. T. M. The Importance of Nickel Oxyhydroxide Deprotonation on Its Activity towards Electrochemical Water Oxidation. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7 (4), 2639–2645. 10.1039/C5SC04486C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wencel D.; Abel T.; McDonagh C. Optical Chemical pH Sensors. Anal. Chem. 2014, 86 (1), 15–29. 10.1021/ac4035168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L.; Li M.; Li W.; Han Y.; Liu Y.; Li Z.; Zhang B.; Pan D. Rationally Designed Efficient Dual-Mode Colorimetric/Fluorescence Sensor Based on Carbon Dots for Detection of pH and Cu2+ Ions. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2018, 6 (10), 12668–12674. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b01625. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mirkin M. V.; Horrocks B. R. Electroanalytical Measurements Using the Scanning Electrochemical Microscope. Anal. Chim. Acta 2000, 406 (2), 119–146. 10.1016/S0003-2670(99)00630-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ayemoba O.; Cuesta A. Spectroscopic Evidence of Size-Dependent Buffering of Interfacial pH by Cation Hydrolysis during CO2 Electroreduction. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9 (33), 27377–27382. 10.1021/acsami.7b07351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J.; Ma H. Design Principles of Spectroscopic Probes for Biological Applications. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7 (10), 6309–6315. 10.1039/C6SC02500E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang K.; Kas R.; Smith W. A. In Situ Infrared Spectroscopy Reveals Persistent Alkalinity near Electrode Surfaces during CO2 Electroreduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141 (40), 15891–15900. 10.1021/jacs.9b07000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd N. C.; Cannan S.; Bitziou E.; Ciani I.; Whitworth A. L.; Unwin P. R. Fluorescence Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy as a Probe of pH Gradients in Electrode Reactions and Surface Activity. Anal. Chem. 2005, 77 (19), 6205–6217. 10.1021/ac050800y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuladpanjeh-Hojaghan B.; Elsutohy M. M.; Kabanov V.; Heyne B.; Trifkovic M.; Roberts E. P. L. In-Operando Mapping of pH Distribution in Electrochemical Processes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58 (47), 16815–16819. 10.1002/anie.201909238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowyer W. J.; Xie J.; Engstrom R. C. Fluorescence Imaging of the Heterogeneous Reduction of Oxygen. Anal. Chem. 1996, 68 (13), 2005–2009. 10.1021/ac9512259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakooei S.; Ismail C.; Ari-Wahjoedi B. An Overview of pH Sensors Based on Iridium Oxide: Fabrication and Application. Int. J. Mater. Sci. Innov. 2013, 1 (1), 62–72. [Google Scholar]

- Nadappuram B. P.; McKelvey K.; Al Botros R.; Colburn A. W.; Unwin P. R. Fabrication and Characterization of Dual Function Nanoscale pH-Scanning Ion Conductance Microscopy (SICM) Probes for High Resolution pH Mapping. Anal. Chem. 2013, 85 (17), 8070–8074. 10.1021/ac401883n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouattara L.; Fierro S.; Frey O.; Koudelka M.; Comninellis C. Electrochemical Comparison of IrO2 Prepared by Anodic Oxidation of Pure Iridium and IrO2 Prepared by Thermal Decomposition of H2IrCl6 Precursor Solution. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2009, 39 (8), 1361–1367. 10.1007/s10800-009-9809-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W. D.; Cao H.; Deb S.; Chiao M.; Chiao J. C. A Flexible pH Sensor Based on the Iridium Oxide Sensing Film. Sens. Actuators, A 2011, 169 (1), 1–11. 10.1016/j.sna.2011.05.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jović M.; Hidalgo-Acosta J. C.; Lesch A.; Costa Bassetto V.; Smirnov E.; Cortés-Salazar F.; Girault H. H. Large-Scale Layer-by-Layer Inkjet Printing of Flexible Iridium-Oxide Based pH Sensors. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2018, 819, 384–390. 10.1016/j.jelechem.2017.11.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss A.; Nagy G. Deconvolution in Potentiometric SECM. Electroanalysis 2015, 27 (3), 587–590. 10.1002/elan.201400598. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jovanovič P.; Hodnik N.; Ruiz-Zepeda F.; Arčon I.; Jozinović B.; Zorko M.; Bele M.; Šala M.; Šelih V. S.; Hočevar S.; et al. Electrochemical Dissolution of Iridium and Iridium Oxide Particles in Acidic Media: Transmission Electron Microscopy, Electrochemical Flow Cell Coupled to Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry, and X-Ray Absorption Spectroscopy Study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139 (36), 12837–12846. 10.1021/jacs.7b08071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam A. U.; Qin Y.; Nambiar S.; Yeow J. T. W.; Howlader M. M. R.; Hu N. X.; Deen M. J. Polymers and Organic Materials-Based pH Sensors for Healthcare Applications. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2018, 96, 174–216. 10.1016/j.pmatsci.2018.03.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morris C. A.; Chen C. C.; Ito T.; Baker L. A. Local pH Measurement with Scanning Ion Conductance Microscopy. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2013, 160 (8), H430–H435. 10.1149/2.028308jes. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vishnu N.; Kumar A. S.; Pan G. T.; Yang T. C. K. Selective Electrochemical Polymerization of 1-Napthylamine on Carbon Electrodes and Its pH Sensing Behavior in Non-Invasive Body Fluids Useful in Clinical Applications. Sens. Actuators, B 2018, 275, 31–42. 10.1016/j.snb.2018.08.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zuaznabar-Gardona J. C.; Fragoso A. A Wide-Range Solid State Potentiometric pH Sensor Based on Poly-Dopamine Coated Carbon Nano-Onion Electrodes. Sens. Actuators, B 2018, 273, 664–671. 10.1016/j.snb.2018.06.103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lindino C. A.; Bulhões L. O. S. The Potentiometric Response of Chemically Modified Electrodes. Anal. Chim. Acta 1996, 334 (3), 317–322. 10.1016/S0003-2670(96)00360-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu J.; Wuttig A.; Surendranath Y. Quantification of Interfacial pH Variation at Molecular Length Scales Using a Concurrent Non-Faradaic Reaction. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57 (30), 9300. 10.1002/anie.201802756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama Y.; Miyazaki K.; Miyahara Y.; Fukutsuka T.; Abe T. In Situ Measurement of Local pH at Working Electrodes in Neutral pH Solutions by the Rotating Ring-Disk Electrode Technique. ChemElectroChem 2019, 6, 4750–4756. 10.1002/celc.201900759. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo M. C.; Arán-Ais R. M.; Climent V.; Kallio T.; Feliu J. M. Evidence of Local pH Changes during Ethanol Oxidation at Pt Electrodes in Alkaline Media. ChemElectroChem 2015, 2 (9), 1254–1258. 10.1002/celc.201500151. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu M.; Compton R. G. Voltammetric pH Sensor Based on an Edge Plane Pyrolytic Graphite Electrode. Analyst 2014, 139 (10), 2397–2403. 10.1039/C4AN00147H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu M.; Compton R. G. Voltammetric pH Sensing Using Carbon Electrodes: Glassy Carbon Behaves Similarly to EPPG. Analyst 2014, 139 (18), 4599–4605. 10.1039/C4AN00866A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildgoose G. Anthraquinone-Derivatised Carbon Powder: Reagentless Voltammetric pH Electrodes. Talanta 2003, 60 (5), 887–893. 10.1016/S0039-9140(03)00150-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pöller S.; Schuhmann W. A Miniaturized Voltammetric pH Sensor Based on Optimized Redox Polymers. Electrochim. Acta 2014, 140, 101–107. 10.1016/j.electacta.2014.03.116. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Botz A.; Clausmeyer J.; Öhl D.; Tarnev T.; Franzen D.; Turek T.; Schuhmann W. Local Activities of Hydroxide and Water Determine the Operation of Silver-Based Oxygen Depolarized Cathodes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57 (38), 12285–12289. 10.1002/anie.201807798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalak M.; Kurel M.; Jedraszko J.; Toczydlowska D.; Wittstock G.; Opallo M.; Nogala W. Voltammetric pH Nanosensor. Anal. Chem. 2015, 87, 11641–11645. 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b03482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Voogd J. M.; Van Spronsen M. A.; Kalff F. E.; Bryant B.; Ostojic O.; Den Haan A. M. J.; Groot I. M. N.; Oosterkamp T. H.; Otte A. F.; Rost M. J. Fast and Reliable Pre-Approach for Scanning Probe Microscopes Based on Tip-Sample Capacitance. Ultramicroscopy 2017, 181, 61–69. 10.1016/j.ultramic.2017.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro M. C. O.; Koper M. T. M. Alumina Contamination through Polishing and Its Effect on Hydrogen Evolution on Gold Electrodes. Electrochim. Acta 2019, 325, 134915. 10.1016/j.electacta.2019.134915. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobse L.; Raaijman S. J.; Koper M. T. M. The Reactivity of Platinum Microelectrodes. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18 (41), 28451–28457. 10.1039/C6CP05361K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsumi H.; Furumoto S.; Morita M.; Matsuda Y. Electrochemical Behavior of a 4-Nitrothiophenol Modified Electrode Prepared by the Self-Assembly Method. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1995, 171 (2), 505–511. 10.1006/jcis.1995.1209. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Touzalin T.; Joiret S.; Maisonhaute E.; Lucas I. T. Complex Electron Transfer Pathway at a Microelectrode Captured by in Situ Nanospectroscopy. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89 (17), 8974–8980. 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b01542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb S. J.; Ayres Z. J.; Newton M. E.; Macpherson J. V. Deconvoluting Surface-Bound Quinone Proton Coupled Electron Transfer in Unbuffered Solutions: Toward a Universal Voltammetric pH Electrode. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141 (2), 1035–1044. 10.1021/jacs.8b11518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amphlett J. L.; Denuault G. Scanning Electrochemical Microscopy (SECM): An Investigation of the Effects of Tip Geometry on Amperometric Tip Response. J. Phys. Chem. B 1998, 102 (49), 9946–9951. 10.1021/jp982829u. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Izquierdo J.; Knittel P.; Kranz C. Scanning Electrochemical Microscopy: An Analytical Perspective. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2018, 410 (2), 307–324. 10.1007/s00216-017-0742-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballesteros Katemann B.; Schulte A.; Calvo E. J.; Koudelka-Hep M.; Schuhmann W. Localised Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy with High Lateral Resolution by Means of Alternating Current Scanning Electrochemical Microscopy. Electrochem. Commun. 2002, 4 (2), 134–138. 10.1016/S1388-2481(01)00294-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eckhard K.; Schuhmann W. Alternating Current Techniques in Scanning Electrochemical Microscopy (AC-SECM). Analyst 2008, 133 (11), 1486–1497. 10.1039/b806721j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maljusch A.; Senöz C.; Rohwerder M.; Schuhmann W. Combined High Resolution Scanning Kelvin Probe — Scanning Electrochemical Microscopy Investigations for the Visualization of Local Corrosion Processes. Electrochim. Acta 2012, 82, 339–348. 10.1016/j.electacta.2012.05.134. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Critelli R. A. J.; Bertotti M.; Torresi R. M. Probe Effects on Concentration Profiles in the Diffusion Layer: Computational Modeling and near-Surface pH Measurements Using Microelectrodes. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 292, 511–521. 10.1016/j.electacta.2018.09.157. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.