Short abstract

Background

Inadequate titers of pneumococcal antibody (PA) are commonly present among patients with recurrent respiratory infections.

Objective

We sought to determine the effect of the degree of inadequacy in baseline PA titers on the subsequent polysaccharide vaccine response, the incidence of sinusitis, and allergic conditions.

Methods

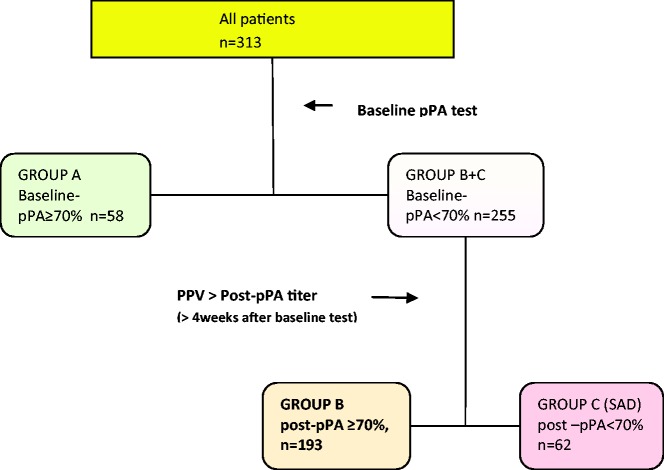

A total of 313 patients aged 6 to 70 years with symptoms of recurrent respiratory infections were classified by baseline-pPA (percentage of protective [≥1.3 µg/mL] PA serotypes/total tested serotypes) and postvaccination pPA (post-pPA): Group A (adequate baseline-pPA), Group B (inadequate baseline-pPA, adequate post-pPA, responders), and Group C (inadequate baseline-pPA, inadequate postpPA, nonresponders, specific antibody deficiency [SAD]). Immunity against Streptococcus pneumoniae was defined as adequate when the pPA was ≥70%. Each group and combined groups, Group AB (inadequate baseline-pPA), and Group BC (adequate post-pPA) were analyzed for demographics, history of sinusitis, recurrent sinusitis in the following year, allergic conditions, and association with inadequate individual serotype titers.

Results

Over 80% of patients with respiratory symptoms had inadequate baseline-pPA. Baseline-pPA and SAD prevalence are inversely related (odds ratio = 2.02, 95% CI: 1.15–3.57, P = .01). Inadequate serotype 3 antibody titer is highly associated with SAD (odds ratio = 2.02, 96% CI: 1.61–5.45, P < .01). The groups with inadequate pPA (Group B and C, or BC) had significantly higher percentage of patients with chronic rhinosinusitis (P < .001), allergic sensitization, and allergic rhinitis (P < .05). Group A contained higher percentage of patients with recurrent upper airway infections (P < .001).

Conclusion

Low baseline-pPA and low antibody titers to serotype 3 are highly associated with SAD, increased incidence of respiratory infections including CRS and allergic conditions.

Keywords: specific antibody deficiency, asthma, allergic rhinitis, recurrent respiratory infection, immune deficiency, sinusitis, chronic rhinosinusitis

It is known that patients with recurrent respiratory infections may have inadequate pneumococcal antibody (PA) titers representing poor state of defense against polysaccharide bacteria.1–3 For these patients, polysaccharide pneumococcal vaccine (PPV) is recommended for evaluation and boosting of independent humoral immunity.4 Subjects with inadequate vaccine response, but with normal levels of immunoglobulins and IgG subclasses in the absence of other primary or secondary immunodeficiencies, are classified as having specific antibody deficiency (SAD).4–6 Although the guidelines by the working group of experts consider vaccine responses of PA titer > 1.3 ng/mL in <70% of total tested PAs for patients aged 6 to 65 years as inadequate response (SAD),4,5 there is still controversy as to what constitutes adequate immune state. The immune state of a patient at a given time needs to reflect PA titers resulting from both vaccination and responses from natural exposures to Streptococcus pneumoniae. The evaluation of a response to polysaccharide antigen involves assessment of the concentration and function of each antibody to diverse serotypes of varying immunogenicity. Even the accuracy of PA testing methods has been questioned.7,8 Although previous studies mainly reported association between chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) and SAD, we broadened our study to include patients with not only CRS but chronic respiratory symptoms. The goal of our study was to find the relationship between the antibody titers of commonly tested serotypes resulting from both vaccination and natural exposures, as an individual and as a group, and the clinical conditions in a time line surrounding the initial and vaccination visits.

Methods

Study Design

This retroactive study was performed using electronic medical chart review of patients seen between 2008 and 2018 at an allergy-immunology clinic in Los Angeles, California. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and Human Subjects Committee at LA Biomedical Institute at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center.

As all patients who presented with recurrent respiratory symptoms were screened with PA profiles, the Current Procedural Terminology code for PA testing was used for initial capture of the study population. These charts were further reviewed for the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Patients aged 6 to 70 years were included if they had history suggesting respiratory infection: chronic cough (>4 weeks), persistent rhinitis (>4 weeks), chronic sinusitis (CRS; >12 weeks), and recurrent acute sinusitis (RAS; >1 time/year). Patients with history of malignancy, autoimmune disorder, or primary/secondary immunodeficiency were excluded.

Classification of the Subjects’ Clinical Conditions

The diagnosis of sinusitis was made when a patient met the widely used criteria9 of positive history of sinusitis and nasal endoscopy or sinus CT scan. Sinusitis was classified into acute or chronic sinusitis using 12 weeks’ duration as the threshold. Since many patients had both chronic and acute sinusitis at separate times, the CRS category was defined as CRS with or without acute sinusitis. RAS was defined as >1 episode of acute sinusitis/year without CRS. Recurrent upper airway infection (RU) was defined as upper respiratory infection (URI) symptoms lasting <2 weeks occurring >4 times/year. Symptoms suggestive of sinusitis without meeting the criteria were categorized as no infection (NI) category. There was only 1 patient with a diagnosis of pneumonia in the study and was excluded from the analysis.

Classification of the Subjects’ Immune Status by Laboratory Testing

Immune status was evaluated with levels of immunoglobulins (Igs) G, A, M, and E, and of IgG antibodies to S. pneumoniae and Clostridium tetani (Luminex Assay, by LabCorp for 89% of the patients and Quest Diagnostics for the rest). Baseline and subsequent tests were performed by the same laboratory. In patients evaluated prior to 2010, 14 serotypes were reported: 1, 3, 4, 5, 8, 9(9N), 12(12F), 14, 19(19F), 23(23F), 26(6B), 51(7F), 56(18C), and 68(9V). After 2010, 23 serotypes were reported: 1, 3, 4, 8, 9(9N), 12(12F), 14, 17(17F), 19(19F), 2, 20, 22(22F), 23(23F), 26(6B), 34(10A), 43(12), 5, 51(7F), 54(15B), 56(18C), 57(19A), 68(9V), and 70 33F). Based on the consensus by the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology working group,4,5 a protective PA titer was defined as ≥1.3 µg/mL; percentage of protective PA (pPA) ≥70% were considered adequate regardless of history of prior immunization with either unconjugated (polysaccharide pneumococcal vaccine [PPV]-23) or conjugated vaccine (pneumococcal conjugated vaccine [PCV]-7 or -13). Thereafter, patients were divided into 3 groups: A (adequate baseline-pPAs), B (inadequate baseline-PAs with adequate post-PAs, responders), and C (inadequate baseline- and post-PAs, SAD) (see Figure 1). Group C was treated with PCV and tested for postvaccinating PA titers. These groups were also analyzed as combinations: Group AB (Group A and Group B, non-SAD) versus Group C (SAD) as well as Group A (adequate baseline-pPA) versus Group BC (Group B and Group C, inadequate baseline-pPA).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of all patients classified by baseline and post-pPA (post-vaccination percentage of protective pneumococcal antibody). Group A, adequate baseline-pPA; Group B, inadequate baseline-pPA with adequate post-pPA; Group C, inadequate post-pPA, SAD; pPA = percentage of protective (≥1.3 µg/mL) pneumococcal antibody serotypes to total tested serotypes; PPV, polysaccharide pneumococcal vaccine; SAD, specific antibody deficiency.

Evaluation of Subjects’ Allergic Conditions

Allergy skin tests were performed using 16-40 standard indoor and outdoor inhalant allergens present in Southern California. Total serum IgE and specific IgEs to inhalant allergens for Southern California (LabCorp, Burlington, North Carolina) were used to detect the kind and degree of sensitization. The diagnosis of asthma or rhinitis was based on the relevant ICD 9 or 10 code or clinical history. Allergic designation of these diagnoses was based on the presence of positive reaction to any allergen(s) on the skin test or in the laboratory report of specific serum IgE.

Statistical Analysis

Patient characteristics were described by individual groups, A, B, and C, and as combined groups, AB and BC. Median, interquartile markers, and Mann–Whitney test results were reported for continuous variables while frequencies, column percentages, and χ2 test results were reported for categorical variables. A multivariable logistic regression model was used to determine the associations between the outcomes Group C versus Group AB, Group A versus Group BC, and the variables (age, CRS, RAS, RU, allergy sensitization, asthma [allergic vs nonallergic], rhinitis [allergic vs nonallergic], and individual serotypes). Multivariable logistic regression models were also utilized to determine the association between baseline-pPA values and the patients’ response to PPV (SAD as an outcome), and the difference in the recurrence rate of sinusitis in 1-year follow-up (outcome) among the 3 groups. SAS version 9.4 (Cary, North Carolina) was used for all analyses.

Results

Patient Demographics, Prevalence of SAD, and Other Clinical Conditions

A total of 313 patients with recurrent respiratory symptoms were studied; the median age was 34 years with 86% whites and 64% females (Table 1). Patients with SAD was older than non-SAD patients (median age = 41 vs 34, P < .01). Among these, 143 were identified with diagnosis of CRS. SAD was present in 20% (n = 62) among the whole group, among which 31% (11/35) had adequate response to PCV. The prevalence of SAD was increased in CRS (26%, n = 37) and RAS (18%, n = 11) compared to RU (11%, n = 6) and NI (14%, n = 10); (P<.05). The prevalence of SAD among patients with asthma (21%, 28/134) or rhinitis (AR/NAR; 19%, 46/242) was not different compared to those without these conditions (19%, 46/242 or 23%,16/71, P > .6 for both).

Table 1.

Demographics and Clinical/Laboratory Characterization of Study Subjects by Postvaccination Responses.

| Number of Patients(% of total patient number) | Group A: Adequate baseline-pPA | Group B: Adequate post-pPA | Group C: Inadequate post-pPA (SAD) | Total P Value | P Value: Group A vs Group B | P Value: Group A vs Group C | P Value: Group B vs Group C | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient cohort (%) | 313 | 58 (19) | 193 (62) | 62 (20) | ||||

| Median age | 34 | 31 | 35 | 41 | .02 | .54 | .06 | .006 |

| Ethnicity (white /other) | 268/45 | 51/7 | 163/30 | 54/8 | .75 | .51 | .89 | .62 |

| Male/female | 111/202 | 15/43 | 73/120 | 23/39 | .24 | .09 | .18 | .91 |

| Recurrent infection (%) | 241 (77) | 43 (74) | 146 (76) | 52 (84) | .35 | .81 | .19 | .18 |

| No infection (%) | 72 (23) | 15 (26) | 47 (24) | 10 (14) | .35 | .81 | .19 | .18 |

| Chronic rhinosinusitis (%) | 143(45) | 15 (26) | 91 (47) | 37 (60) | .0008 | .04 | .0002 | .08 |

| Recurrent acute sinusitis (%) | 61 (24) | 12 (21) | 38 (20) | 11 (18) | .91 | .87 | .68 | .74 |

| Recurrent upper respiratory infection (%) | 37(12) | 16 (27) | 17 (9) | 4 (6) | .03 | .0002 | .002 | .56 |

| Allergy sensitization (%) | 194 (62) | 29 (50) | 128 (66) | 37 (60) | .07 | .02 | .29 | .34 |

| Asthma (%) | 134 (43) | 25 (43) | 81 (42) | 28 (45) | .90 | .88 | .82 | .66 |

| Allergic asthma (%) | 100 (32) | 13 (22) | 66 (34) | 21 (34) | .23 | .09 | .16 | .96 |

| Rhinitis (allergic and nonallergic) (%) | 242 (77) | 43 (74) | 153 (79) | 46 (74) | .58 | .41 | .99 | .4 |

| Allergic rhinitis (%) | 177 (57) | 26 (45) | 120 (62) | 31 (50) | .03 | .019 | .5 | .08 |

Abbreviations: pPA, percentage of protective (≥1.3 µg/mL) pneumococcal antibody serotypes/total tested serotypes; SAD, specific antibody deficiency.

Bold values indicate statistical significance (P < .05). Baseline-pPA denotes prevaccination pPA and post-pPA denotes postvaccination pPA.

Prevalence of Sinusitis and Allergic Conditions Among 3 Immunological Groups

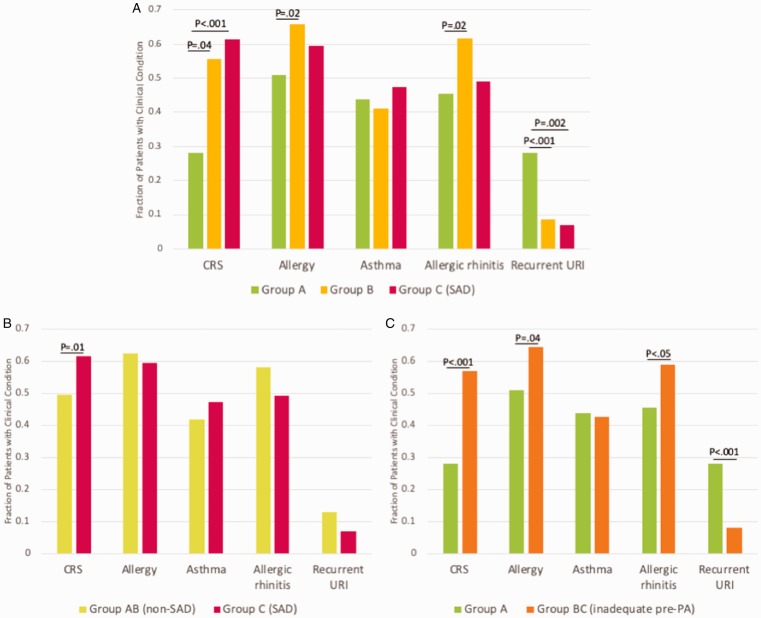

Among individual groups (Group A, B, C) patients with CRS were represented in higher proportion in Group B and C as compared to Group A (47% and 60% vs 26%, P < .01; Table 1 and Figure 2(A)). Group A contained higher proportion of patients with RUs (P < .05). The prevalence of rhinitis, asthma, and allergic asthma was not different among the groups, but allergy skin sensitization and allergic rhinitis were more common among Group B compared to Group A (P < .05).

Figure 2.

Prevalence of clinical conditions among different groups. A, Percentage of clinical conditions among Group A, B, and C. B, Percentage of clinical conditions among Group AB versus C. C, Percentage of clinical conditions among Group A versus BC.

CRS, chronic rhinosinusitis; Group A, adequate baseline-PAs; Group B, inadequate baseline-PAs with adequate post-PAs, responders; Group C, inadequate baseline- and post-PAs, SAD; Group AB, Group A + Group B: the groups with post-pPA ≥70%; Group BC, Group B + Group C: the group with baseline-pPA <70%; PA, pneumococcal antibody; SAD, specific antibody deficiency; URI, upper respiratory infection.

Impact of Baseline-pPA and SAD on Clinical Conditions

Between Group A (adequate baseline-pPA) versus Group BC (inadequate baseline-pPA; Figure 2(C) and Table 2): The percentage of CRS was higher among Group BC (P < .001). Group A contained higher percentage of patients with RU (P <.001). The prevalence of allergic sensitization and AR were increased in Group BC (P <.05).

Table 2.

Demographics and Clinical/Laboratory Characterization of Study Subjects by Postvaccination Responses: Group A versus Group BC (Inadequate Baseline-pPA vs Adequate Baseline-pPA).

| Group A: Adequate Baseline-pPA | Group BC: Inadequate Baseline-pPA | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient cohort (%) | 58 (24) | 255 (76) | |

| Median age | 31 | 37 | .80 |

| Ethnicity (white /other) | 51/7 | 217/38 | .58 |

| Male/female | 15/43 | 96/159 | .09 |

| Recurrent infection (%) | 43 (74) | 198 (78) | .57 |

| No infection (%) | 15 (26) | 47 (22) | .35 |

| Chronic rhinosinusitis (%) | 15 (26) | 128 (50) | .001 |

| Recurrent acute sinusitis (%) | 12(21) | 49 (19) | .80 |

| Recurrent upper respiratory infection (%) | 20(34) | 40 (16) | .001 |

| Allergy sensitization (%) | 29(50) | 165 (65) | .04 |

| Asthma (%) | 25(43) | 109 (43) | .96 |

| Allergic asthma (%) | 13 (22) | 87 (34) | .08 |

| Rhinitis (allergic and nonallergic) (%) | 43 (74) | 199 (78) | .52 |

| Allergic rhinitis (%) | 26 (45) | 151 (59) | .04 |

Abbreviation: pPA, percentage of protective (≥1.3 µg/mL) pneumococcal antibody serotypes/total tested serotypes.Note: Bold values indicate statistical significance.

Between SAD group (Group C) and non-SAD group (Group AB; Figure 2(B) and Table 3): The percentage of CRS was higher in SAD group (P < .05). The percentages of patients with allergic conditions were not different between the 2 groups.

Table 3:

Demographics and Clinical/Laboratory Characterization of Study Subjects by Postvaccination Responses: SAD (Group C, inadequate post-pPA) versus Non-SAD (Group AB, adequate post-pPA).

| Group AB: Adequate Baseline-pPA (Non-SAD) | Group C: Adequate Post-pPA (SAD) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient cohort (%) | 251 (80) | 62 (20) | |

| Median age | 34 | 41 | .003 |

| Ethnicity (white /other) | 214/37 | 54/8 | .71 |

| Male/female | 88/163 | 23/39 | .76 |

| Recurrent infection (%) | 189 (75) | 52 (84) | .15 |

| No infection (%) | 62 (25) | 10 (16) | .2 |

| Chronic rhinosinusitis (%) | 106 (42) | 37 (60) | .014 |

| Recurrent acute sinusitis (%) | 50 (20) | 11 (18) | .70 |

| Recurrent upper respiratory infection (%) | 53(21) | 7 (11) | .08 |

| Allergy sensitization (%) | 94 (37) | 25 (40) | .68 |

| Asthma (%) | 106 (42) | 28 (45) | .68 |

| Allergic asthma (%) | 79 (31) | 21 (34) | .72 |

| Rhinitis (allergic and nonallergic) (%) | 196 (78) | 46 (74) | .51 |

| Allergic rhinitis (%) | 146 (58) | 31 (50) | .25 |

Abbreviations: pPA, percentage of protective (≥1.3 μg/mL) pneumococcal antibody serotypes/total tested serotypes; SAD: specific antibody deficiency.Note: Bold values indicate statistical significance.

Patterns of Recurrent Sinusitis During the 1 Year Following the Initial Visit Among 3 Immunological Groups of Sinusitis Patients

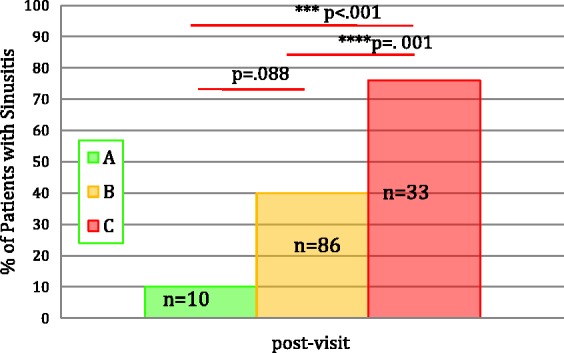

Among 143 patients with CRS, there were significant differences in the recurrence of sinusitis based on the use of antibiotics among Groups A, B, and C (Figure 3 and Table 4). Group A had the lowest percentage of patients with recurrence requiring antibiotic treatment (10%). The percentage of patients with recurrence of sinusitis was higher in Group B even after pPAs were normalized (40%), although P value did not reach the significance (P = .09, probably due to small number of subjects in Group A). Finally, Group C had the highest percentage of patients with recurrences (76%) (Group A vs B: P = .088, Group A vs C: P < .001, Group B vs C: P < .001) and higher trend for sinus surgery (Group B vs C: P = .09, numbers too small). In Group C, patients with inadequate response to PCV had more severe courses requiring more antibiotics and immunoglobulin replacement compared to nonresponder, although the numbers were too small for statistics.

Figure 3.

Percentage of patients with CRS during the 1 year after the initial visit (n = 143). A, Group A (adequate baseline-PAs); B, Group B (inadequate baseline-PAs with adequate post-PAs, responders); C, Group C (inadequate baseline- and post-PAs, SAD); n, number of patients who returned for follow-up visits.

Table 4.

Recurrence of Sinusitis (Antibiotics Treatment) in 1-Year Follow-up of Patients Who Presented With Sinusitis (n = 143).

| Group | n | Abx rx-1 | Abx rx-2+ | PatientsTreated With Abx in the Next Year | Total Number of Abx (Average/Patient) | Patients With Adequate Response to PCVa | Surgery | Prophylactic Abx | Ig Rx | No Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 15 | 1/10 (10%) | 0 | 1 (10%) | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 5/15 (33%) | |||

| B | 91 | 30/86 (34%) | 4/86 (5%) | 34/86 (40%) | 38/86 (0.40) | 2/86 (2%) | 5/91 (5%) | |||

| C | 37 | 13/33 (40%) | 12/33 (36%) | 25/33 (76%) | 37/33 (1.1) | 8/22 | 4/33 (12%) | 4/33 (12%) | 3/33 (9%) | 4/37 (11%) |

Abbreviations: abx rx-1, antibiotic treatment once in the next 1 year; abx rx-2+, antibiotics treatment twice or more in the next 1 year; Ig rx, immunoglobulin replacement therapy; n, number of patients.

P value for difference of recurrences among groups (Fisher test): Among Group A versus Group B: <.001, Group A versus Group B = .088, Group A versus Group C < .001.

aAll 37 patients were given PCV. Among these, 33 returned for follow-up appointments, and 22 had postvaccination PA titers tested; 14 of 22 had inadequate responses. These nonresponders compared to responders (n = 8) had more severe clinical courses (P value not done due to small numbers). Nonresponders (n = 14): Total number of abx, 15; surgery, 2; Ig rx = 3. Responders (n = 8): Total number of abx, 6; surgery, 2; Ig rx = 1.

Baseline-pPA as a Predictor for Post-PA Responses

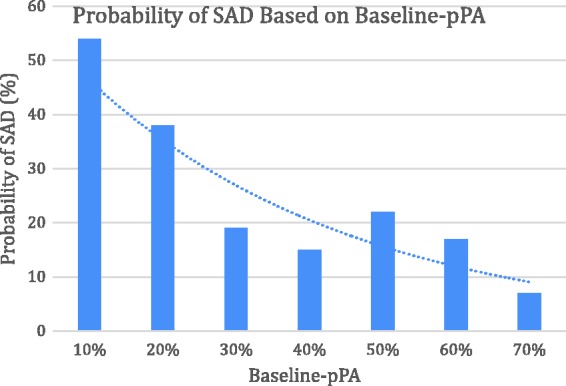

A large proportion of our subjects had inadequate baseline-pPAs (Group BC/total subjects = 81%) regardless of prior immunization history (Table 1). The median baseline-pPAs were 0.85, 0.35, and 0.21 for Groups A, B, and C, respectively (with P < .01 between Group A and C, P = .01 between Groups B and C). The prevalence of SAD was inversely related to baseline-pPA, suggesting patients with decreased baseline-pPA were more likely to develop SAD (Figure 4; odds ratio = 2.02, 95% CI: 1.15–3.57, P = .01, n = 255).

Figure 4.

Probability of SAD based on baseline-pPA. Logistic regression test was used with inadequate baseline-pPAs from Group B and C as the independent variable (x-axis) and probability of SAD (%) as the dependent variable (y-axis). The data showed that the lower the baseline PA, the higher the probability of SAD (odds ratio = 2.02, 95% CI: 1.15–3.57, P = .01, n = 37). pPA, percentage of protective (≥1.3 µg/mL) pneumococcal antibody serotypes to total tested serotypes; SAD, specific antibody deficiency.

Pattern of Inadequate Baseline PA Titers to Individual Isotypes in 3 Immunological Groups

Among 23 serotypes, inadequate baseline PAs to serotype 3,19, and 23 distinguished Group C from Group B and Group A (P < .05) and, of note, an inadequate titer of serotype 3 was the most important predictor of SAD (with Bonferroni-adjusted P value = .017). The frequencies of inadequate baseline-PA to serotype 3 were 7% (n = 4) in Group A, 44% (n = 84) in Group B, and 65% (n = 40) in Group C (Table 5).

Table 5.

Number of Patients With Adequate Baseline-pPA to Individual Serotypes in Group A, B, and C.

| Strainsa | Number of Patients in Group A | Number of Patients in Group B | Number of Patients With Group C | Overall P Value | P Value: Group A vs B | P Value: Group A vs C | P Value: Group B vs C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain 1 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | .458 | |||

| 1 | 3 | 110 | 32 | ||||

| 0 | 55 | 83 | 30 | ||||

| Strain3 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | .004 | |||

| 1 | 54 | 109 | 22 | ||||

| 0 | 4 | 84 | 40 | ||||

| Strain4 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | .4395 | |||

| 1 | 36 | 35 | 14 | ||||

| 0 | 22 | 158 | 48 | ||||

| Strain5 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | .5028 | |||

| 1 | 53 | 84 | 30 | ||||

| 0 | 5 | 109 | 32 | ||||

| Strain8 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | .1574 | |||

| 1 | 52 | 62 | 26 | ||||

| 0 | 6 | 131 | 36 | ||||

| Strain9 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | .7508 | |||

| 1 | 54 | 49 | 17 | ||||

| 0 | 4 | 144 | 45 | ||||

| Strain12 | <.0001 | <.0001 | .0155 | .2725 | |||

| 1 | 24 | 29 | 13 | ||||

| 0 | 34 | 164 | 49 | ||||

| Strain14 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | .1759 | |||

| 1 | 57 | 100 | 26 | ||||

| 0 | 1 | 93 | 36 | ||||

| Strain19 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | .0306 | |||

| 1 | 56 | 129 | 32 | ||||

| 0 | 2 | 64 | 30 | ||||

| Strain23 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | .0361 | |||

| 1 | 56 | 85 | 18 | ||||

| 0 | 2 | 108 | 44 | ||||

| Strain26 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | .8752 | |||

| 1 | 53 | 80 | 25 | ||||

| 0 | 5 | 113 | 37 | ||||

| Strain51 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | .1163 | |||

| 1 | 55 | 84 | 20 | ||||

| 0 | 3 | 109 | 42 | ||||

| Strain56 | <.0001 | <.0001 | .0765 | ||||

| 1 | 39 | 77 | 17 | ||||

| 0 | 19 | 116 | 45 | ||||

| Strain68 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | .2066 | |||

| 1 | 56 | 61 | 25 | ||||

| 0 | 2 | 132 | 37 | ||||

| Strain17 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | .9187 | |||

| 1 | 58 | 129 | 41 | ||||

| 0 | . | 64 | 21 | ||||

| Strain2 | .0168 | .0043 | .0576 | .4715 | |||

| 1 | 48 | 121 | 42 | ||||

| 0 | 10 | 72 | 20 | ||||

| Strain20 | .0023 | .0005 | .0036 | .8364 | |||

| 1 | 52 | 128 | 42 | ||||

| 0 | 6 | 65 | 20 | ||||

| Strain22 | .0009 | .0002 | .0002 | .9187 | |||

| 1 | 53 | 129 | 41 | ||||

| 0 | 5 | 64 | 21 | ||||

| Strain34 | <.0001 | <.0001 | .0006 | .3689 | |||

| 1 | 55 | 125 | 44 | <.0001 | |||

| 0 | 3 | 68 | 18 | ||||

| Strain43 | .9674 | .7968 | .8733 | .9477 | |||

| 1 | 41 | 133 | 43 | ||||

| 0 | 17 | 60 | 19 | ||||

| Strain54 | .0057 | .0014 | .00081 | .8364 | |||

| 1 | 51 | 128 | 42 | ||||

| 0 | 7 | 65 | 20 | ||||

| Strain57 | .0004 | .0001 | .0002 | .8102 | |||

| 1 | 56 | 140 | 44 | ||||

| 0 | 2 | 53 | 18 | ||||

| Strain70 | .0009 | .0017 | .0002 | .1796 | |||

| 1 | 52 | 133 | 37 | ||||

| 0 | 6 | 60 | 25 |

aStrains: 1 = protective, 0 = nonprotective.Note: Bold values indicate statistical significance.

Discussion

Our analyses found the prevalence of SAD in the range of 14% to 26% depending on the parameter used in line with the literature.10–12 The prevalence of SAD was higher in our patients with respiratory symptoms compared to the one reported for asymptomatic subjects (11%)10 and higher with CRS as compared to patients with only RAS or URIs or NI. It is also important to note that a high percentage (81%) of patients with recurrent upper respiratory symptoms had low baseline PAs and the majority of whom benefitted from vaccination as evidenced by a lower rate of recurrent sinusitis in the following year (Figure 3 and Table 4).

Although efforts to establish the minimum threshold for post-PA response have been made, no clear guidelines exist on PA threshold for adequate immune status at the initial evaluation. Our analysis demonstrates that prevalence of respiratory infections in our patients depends on the level of PA at a given time. Although the working group guidelines recommended using the serotypes present only in PPV in patients who received PCV,4 we used the total reported serotypes regardless of their vaccination status, because we believe that those represents more accurately the current state of vaccine and infection induced immunity. Patients with inadequate pPA (Group A, Group B, and Group BC) have history of more frequent CRS and RS, compared to ones in Group A (Figure 2(C)) suggesting that pPA at the initial visit reflected the recent state of poor immunity against the bacteria. Group B even after normalization of PA by vaccination (despite no difference in the average baseline-pPA of Group A and post-pPA of Group B: 0.87 vs 0.89) tended to have more incidence of sinusitis over the next year compared to Group A. This suggests a persistence of underlying B-cell deficiency. Our analysis predicts that subjects with lower baseline-pPA would have higher probability of qualifying for SAD and more prone for CRS (Figure 4).

Our study demonstrated that vaccine responders experienced lesser incidence of CRS (Figure 2, Table 4) as previously reported in the literature.10,13–16 This indicates the importance of an adequate number of protective titers against S. pneumoniae in the prevention of recurrent or prolonged symptoms since S. pneumoniae is a major pathogen for sinusitis and PAs represent B-cell function against polysaccharide surface antigens present on other major pathogenic bacteria such as Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis.17,18

Among recurrent respiratory infections, CRS was the most common condition, often accompanied by RAS and RU, and was most significantly associated with inadequate baseline-pPA. The presence of RAS or RU in the absence of CRS did not show a strong association. CRS (with or without nasal polyps) is generally considered an inflammatory process with concomitant bacterial infection/colonization of the sinus cavities.19,20 Poor ability of B cells to respond to polysaccharide antigens as well as Th2 (allergic) bias in the host upper airway may be contributory.20,21 Patients with inadequate baseline-pPA experienced significantly less RUs probably suggesting that RU evolved into CRS or RAS rather than staying as an isolated event.

The prevalence of allergic sensitization was much more common among our population with CRS, RAS, or RU (∼60%), which is consistent with previous epidemiological data.11 This is far above the rate of allergic sensitization among the general population as reported by NHANES: 45% in patients aged 6 years or older.22 The prevalence rates of asthma (42%) and rhinitis (77%) were also higher in our total study group as compared to the general population (7%–8% and 20%–30% in the United States).23–25 Although it is tempting to postulate that allergic sensitization might suppress PA response to natural exposures, our data are conflicting as in the literature.10,26 There is a tendency for higher prevalence of allergic sensitization and AR among patients with low pre-PA (Group BC, P < .05). However, when all patients were divided into allergy-sensitized versus nonsensitized group, there was no significant difference in the prevalence of SAD (19% vs 19%) or CRS (41% vs 53%). This contradiction may be explained on the statistical basis. As seen in Figure 2(A), the allergic sensitization was highest in Group B and lowest in Group A. When patients were divided into SAD (Group C) and non-SAD (Group AB) as in Figure 2(B), Group B with the largest number of cohorts might have raised the rate of allergic sensitization for non-SAD group matching that of SAD group.

The pneumococcal polysaccharide capsule is crucial for virulence, primarily by protecting the bacteria against phagocytosis. Serotype 3 is reportedly more immunogenic in young children who are not able to respond to other serotypes.4,27 Our data indicate that inadequate titers to a few serotypes, in particular, to serotype 3, may be a useful predictor of SAD. Contribution of individual or congregational serotypes to the SAD characteristics is not completely understood at this point. These findings needs to be confirmed, since previous efforts to identify selected serotype as representing larger number of serotypes have failed.28

In summary, patients with symptoms of recurrent respiratory symptoms presenting with inadequate baseline-pPA and serotype 3 titer have higher chance of current CRS and not responding to PPV. The lower the initial pPA, the higher chance for SAD and developing CRS subsequently even after normalization of pPA. Further studies are needed to confirm our findings and to identify the potential genetic defects associated with this condition.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by our institutional review board.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Statement of Human and Animal Rights

This article does not contain any studies with animal subjects.

Statement of Informed Consent

This study was conducted by chart review and informed consent is not applicable.

ORCID iD

Charles H. Song https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1060-8127

References

- 1.Hamilos DL. Chronic rhinosinusitis patterns of illness. Clin Allergy Immunol. 2007; 20:1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daly KA, Hoffman HJ, Kvaerner KJet al. Epidemiology, natural history, and risk factors: panel report from the Ninth International Research Conference on Otitis Media. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2010; 74(3):231–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ekdahl K, Braconier JH, Svanborg C. Immunoglobulin deficiencies and impaired immune response to polysaccharide antigens in adult patients with recurrent community-acquired pneumonia. Scand J Infect Dis. 1997; 29(4):401–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orange JS, Ballow M, Stiehm ERet al. Use and interpretation of diagnostic vaccination in primary immunodeficiency: a working group report of the Basic and Clinical Immunology Interest Section of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012; 130(3 Suppl):S1–S24. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2012.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonilla FA, Khan DA, Ballas ZKet al. Practice parameter for the diagnosis and management of primary immunodeficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014; 136(5):1186–1205.e78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Picard C, Bobby Gaspar H, Al-Herz Wet al. International Union of Immunological Societies: 2017 primary immunodeficiency diseases committee report on inborn errors of immunity. J Clin Immunol. 2018; 38(1):96–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whaley MJ, Rose C, Martinez Jet al. Interlaboratory comparison of three multiplexed bead-based immunoassays for measuring serum antibodies to pneumococcal polysaccharides. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2010; 17(5):862–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hajjar J, Al-Kaabi A, Kutac C, Dunn J, Shearer WT, Orange JS. Questioning the accuracy of currently available pneumococcal antibody testing. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018; 142(4):1358–1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fokkens WJ, Lund VJ, Mullol Jet al. European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps 2012. Rhinol Suppl. 2012; 23:3 p preceding table of contents, 1–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keswani A, Dunn NM, Manzur Aet al. The clinical significance of specific antibody deficiency (SAD) severity in chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS). J allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018; 5(4):1105–1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kashani S, Carr TF, Grammer LCet al. Clinical characteristics of adults with chronic rhinosinusitis and specific antibody deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2015; 3(2):236–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Epstein MM, Gruskay F. Selective deficiency in pneumococcal antibody response in children with recurrent infections. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1995; 75(2):125–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glikman D, Dagan R, Barkai Get al. Dynamics of severe and non-severe invasive pneumococcal disease in young children in israel following PCV7/PCV13 introduction. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2018; 37(10):1048–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaplan SL, Barson WJ, Lin PLet al. Early trends for invasive pneumococcal infections in children after the introduction of the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013; 32(3):203–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moberley S, Holden J, Tatham DP, Andrews RM. Vaccines for preventing pneumococcal infection in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013; 2013(1):CD000422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Butler JC, Breiman RF, Campbell JF, Lipman HB, Broome C V, Facklam RR. Pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine efficacy: an evaluation of current recommendations. JAMA. 1993; 270:1826–1831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perez E, Bonilla FA, Orange JS, Ballow M. Specific antibody deficiency: controversies in diagnosis and management. Front Immunol. 2017; 8 (May):586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kainulainen L, Nikoskelainen J, Vuorinen T, Tevola K, Liippo K, Ruuskanen O. Viruses and bacteria in bronchial samples from patients with primary hypogammaglobulinemia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999; 159(4 I):1199–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferguson BJ, Stolz DB. Demonstration of biofilm in human bacterial chronic rhinosinusitis. Am J Rhinol. 2005; 19(5):452–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Zele T, Gevaert P, Watelet JBet al. Staphylococcus aureus colonization and IgE antibody formation to enterotoxins is increased in nasal polyposis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004; 114(4):981–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Drake-Lee AB, McLaughlan P. Clinical symptoms, free histamine and IgE in patients with nasal polyposis. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1982; 69(3):268–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arbes SJ, Gergen PJ, Elliott L, Zeldin DC. Prevalences of positive skin test responses to 10 common allergens in the US population: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005; 116(2):377–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vital signs: asthma prevalence, disease characteristics, and self-management education: United States, 2001–2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2011; 60(17):547–552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salo PM, Calatroni A, Gergen PJet al. Allergy-related outcomes in relation to serum IgE: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005–2006. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011; 127(5):1226–1235.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meltzer EO, Blaiss MS, Derebery MJet al. Burden of allergic rhinitis: results from the Pediatric Allergies in America survey. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009; 124(3 Suppl):S43–S70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boyle RJ, Le C, Balloch A, Tang ML-K. The clinical syndrome of specific antibody deficiency in children. Clin Exp Immunol. 2006; 146(3):486–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carr TF, Koterba AP, Chandra Ret al. Characterization of specific antibody deficiency in adults with medically refractory chronic rhinosinusitis. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2011; 25(4):241–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sorensen RU, Edgar D. Specific antibody deficiencies in clinical practice. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019; 7(3):801–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]