Abstract

Purpose

Hardware infections in orthopedic surgery, specifically those involving biofilm producing bacteria, are troublesome and are highly resistant to systemic antibiotics. The purpose of this study was to demonstrate the power of rifampin and vancomycin solutions in inhibiting as well as eliminating in vitro on staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) biofilm in vitro on stainless-steel implants.

Methods

A suspension of either S. aureus or a S. aureus containing a plasmid that cods for the green fluorescence protein containing fluorescent protein plasmid was applied to 1 × 1cm sterile stainless steel orthopedic plating material (coupon). Biofilm development was confirmed by; the quantitative assay (colony forming unit [CFU/coupon]) and visualized using confocal laser scanning microscopy. With this established method of biofilm development, we determined the minimum biofilm inhibitory concentration (MBIC) and the minimum biofilm eradication concertation (MBEC) of Rifampicin and Vancomycin. To determine the MBIC, stainless steel plates were subjected to different concentrations of antibiotic solution and inoculated with overnight cultures of S. aureus. After 24 h of incubation at 37 °C, the biofilms on the untreated and antibiotic-treated coupons were quantified. To determine the MBEC, partial S. aureus biofilms were developed on the coupons and then treated with the different concentrations of each antibiotic for 24 h. The number of bacteria within the control untreated as well as treated coupons was determined.

Results

Both rifampin and vancomycin solutions inhibited biofilm production of S. aureus on stainless steel mediums; the MBIC for rifampin and vancomycin were 80 ng/mL and 1 μg/mL respectively. The MBEC for Rifampicin was similar to the MBIC. However, the MBEC for Vancomycin was 6 mg/ml.

Conclusions

When applied to orthopedic stainless steel hardware in vitro, solutions of rifampin and vancomycin powder separately or in combination can completely prevent and eliminate biofilm produced by S. aureus.

Level of evidence

II

Keywords: Biofilm, Orthopedics, Infection, Surgery

1. Introduction

Throughout the evolution of modern medicine, the use of medical implants has risen dramatically. The medical implant market is expected to garner $166 billion worldwide by 2022, of which the largest portion of sales will be orthopedic implants.1 While advances in these implants has proved valuable to advancing patient care across numerous specialties, infection of these devices after implantation remains a prominent issue. Medical implant infections are thought to comprise about 50–60% of all nosocomial infections.2 As the medical community has observed for many years, a majority of these infections are caused by Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus), a bacteria that can adhere to implants in clusters and secrete a highly-resistant extracellular membrane known as biofilm.3 Composed of polysaccharides, DNA and proteins, these “cities of bacteria” are highly resistant to systemically administered antibiotics and often allow implant infection to persist until implant is removed. It is estimated that over two million cases of medical implant infections occur each year in the USA alone, producing an annual excess of more than $5 billion in additional health care cost: additional procedures for removal and replacement; additional antibiotics used to eradicate lingering infection; additional hospital stays; additional wage-earning potential lost on the side of the patient. Though there have been numerous studies examining the use of systemic antibiotics to treat these infections, few have yielded successful outcomes.4

Studies examining the physical and chemical properties of biofilm have uncovered many important properties about biofilm that have improved our clinical understanding of its formation and maintenance at a biochemical level. A paracrine phenomenon known as quorum sensing is thought to be the mechanism by which many biofilm producing microbes recruit other bacteria and signal biofilm formation. Greenberg’s group discovered that, through an unknown mechanism, the antibiotic rifampin appears to have an inhibitory effect on quorum sensing at the level of gene expression. Additionally, the popular belief that all biofilm shells were impervious to antibiotic molecules was debunked by the work of Kaplan et al5 These facts have also been explored in a few in vitro studies and suggest that antibiotic beads could be an effective medium for distributing these medications in chronic biofilm-induced infections.6 It is these conclusions that prompted our own research inquiry; could local administration of soluble powder of rifampin, vancomycin, or both, inhibit and/or eliminate the formation of biofilm on orthopedic implant material?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial strains, media, and growth conditions

The Staphylococcus aureus subsp. aureus strain ATCC 29213 was obtained from Remel (Lenexa, KS). S. aureus strain AH133 carries plasmid pCM11 in which the gene for the green fluorescent protein is constitutively expressed (R). For all experiments described in this study, the strains were grown in Luria Britani (LB) broth (R). Bacterial growth and biofilm development were accomplished by incubating the cultures at 37 °C aerobically. A stock solution of Rifampicin was prepare by dissolving powdered Rifampicin in methanol at a concentration of 100 mg/ml. The Vancomycin stock solution was prepared by dissolving powdered Vancomycin in distilled water at a concentration of 1 μg/ml. The antibiotic solutions were filter sterilized. The stock solution was added to the growth medium and biofilm medium to produce the indicated working concentrations (in mg/ml). S. aureus strains were grown in LB broth at 37 °C for 16 h and aliquots were streaked on agar plates to confirm the phenotype. Cells in the broth culture were pelleted, suspended in LB broth containing 20% glycerol, and dispensed in freezer vials. The vials were stored at −80 °C.

2.2. Biofilm development

Static biofilms were developed using the previously described microtiter plate assay (R) with a sight modifications. Sterile stainless steel orthopedics coupons with a 1CM2 area were placed in to each well of sterile Falcon 24-well Polystyrene plates (Becton Dickenson). The coupons were sterilized by rinsing them thoroughly in 95% ethanol followed by a complete air drying at room temperature. If the sterilization was done by autoclaving: The coupons were sterilized using heat steam sterilization. S. aureus strains were grown overnight in LB broth at 37 °C. The cells were pelleted and resuspended in a fresh LB broth to an OD600 of 0.06 and 1 ml of the diluted culture was added to each well of the microtiter plate. The plates were then covered and incubated at 37 °C with gentle shaking on a Titter plate shaker (Lab Line Instruments, Melrose park, IL) for 16 h. For a control, LB broth only was added to some wells of the microtiter plates.

2.3. Analysis of biofilm development

At the end of the incubation period, each coupon was removed from the well of the microtiter plate, rinsed gently in phosphate buffered saline [PBS] to remove loosely attached bacteria from the planktonic culture, and placed in a 2 ml centrifuge tube containing 1 ml of PBS. The microcentrifuge tube was then vigorously vortexed to dislodge the S. aureus biofilm from the coupon. The resulting bacterial suspension was serially diluted (10 fold), 5 ml aliquots from each dilution were spotted on the surface of LB-agar plates, and the plates were incubated at 37 °C for 16 h. Individual colonies from each dilution were counted to determine the colony forming units (CFU). The number of CFU/coupon was determined using the following formula: CFU counted X dilution factor X 100. Biofilms formed by S. aureus AH133 containing the GFP plasmid were visualized by confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) using an Olympus 1X71 Fluoview 300 confocal laser scanning microscope (Olympus).

Determining the Rifampicin and Vancomycin minimum biofilm inhibition concentration (MBIC) and minimum biofilm eradication concentrations (MBEC).

S. aureus strains were grown overnight in LB broth, diluted in a fresh LB broth to an OD600 of 0.006 and inoculated into wells of 24-micrioitre plates containing the stainless steel orthopedics coupons as described above. To determine the MBIC, different concentrations of either Rifampicin or Vancomycin were added to each well immediately after bacterial inoculation (0-time inoculation). After 16 h of incubation at 37 °C, the coupons were removed, rinsed, and the number of CFU/coupon was determined as described above. As a control, few wells were not treated with either antibiotic. The concentration of either Rifampicin or Vancomycin that produced no biofilm (0 CFU/coupon) was considered the MBIC.

To determine the MBEC, the S. aureus strain was inoculated into the microtiter plates as described above and the plates were incubated for 4 h at 37 °C to develop partial biofilm on the stainless steel coupons. After that, the coupons were removed, rinsed in PBS, and added to new wells of a microtiter plate containing fresh LB broth. These wells were divided into two groups; one group received no antibiotics (control) while the other received different concentrations of either Rifampicin or Vancomycin. The plates were incubated for additional 24 h at 37 °C. The coupons were then removed, rinsed in PBS, resuspended in PBS, and vortexed vigorously to dislodge the biofilms as described above. The CFU/coupon was determined using the above described formula. The minimum concentration of either Rifampicin or Vancomycin that eliminated the 4-h partial biofilm (produced 0-CFU/coupon) was considered the MBEC.

To assess the 4-h partial biofilms, some coupons were removed from the wells after the initial 4-h incubation, rinsed, resuspended in PBS, vortexed, and the CFU/coupon was determined.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Parametric variables were expressed as mean and standard deviation. Comparisons between groups were performed by Student’s T-test. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. Data were processed and visualized in GraphPad Prism (version 6.01; GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) (see Fig. 1).

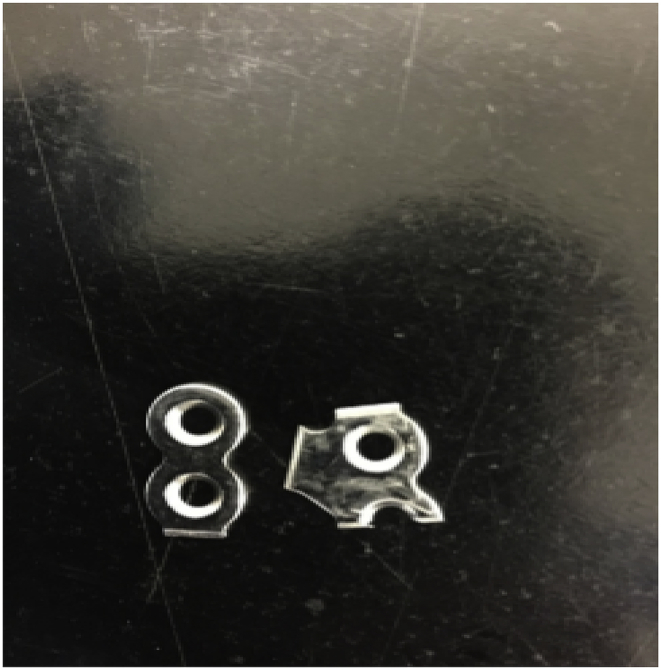

Fig. 1.

Image of the stainless steel orthopedics coupons that were utilized in this study.

3. Results

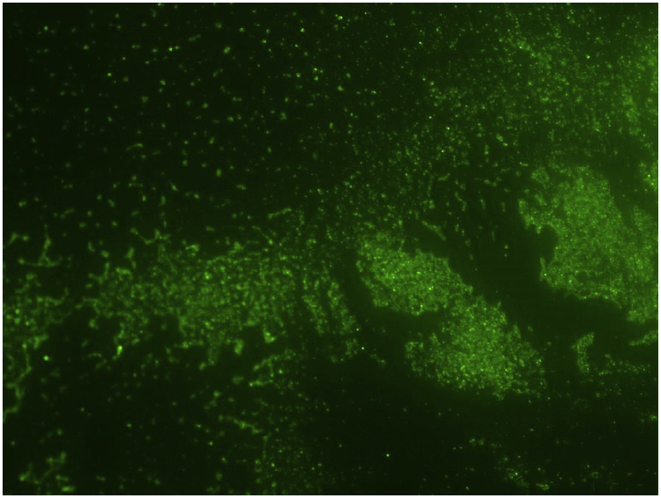

As shown in Fig. 3 and upon 24 h of incubation at 37 °C, S. aureus formed a dense biofilm on the surface of the stainless steel orthopedic coupon (107–108 CFU/coupon). This was confirmed by the confocal laser scanning microscopy of the biofilms (Fig. 2). S. aureus strain AH133 formed a well-developed mature biofilm that covered the entire surface of the coupon (Fig. 2). Both Vancomycin and Rifampicin eliminated biofilm development on the surface of the coupon (Fig. 3, Fig. 5). While S. aureus biofilm on the coupon was 107–108/coupon, no biofilms were formed on the coupon in the presence of 1 mg/ml of Vancomycin and 80 ng of Rifampicin (MBIC) (Fig. 3, Fig. 5). It is clear that Rifampicin is more effective than Vancomycin in eliminating the biofilms MBIC: 80 ng vs. 1 mg).

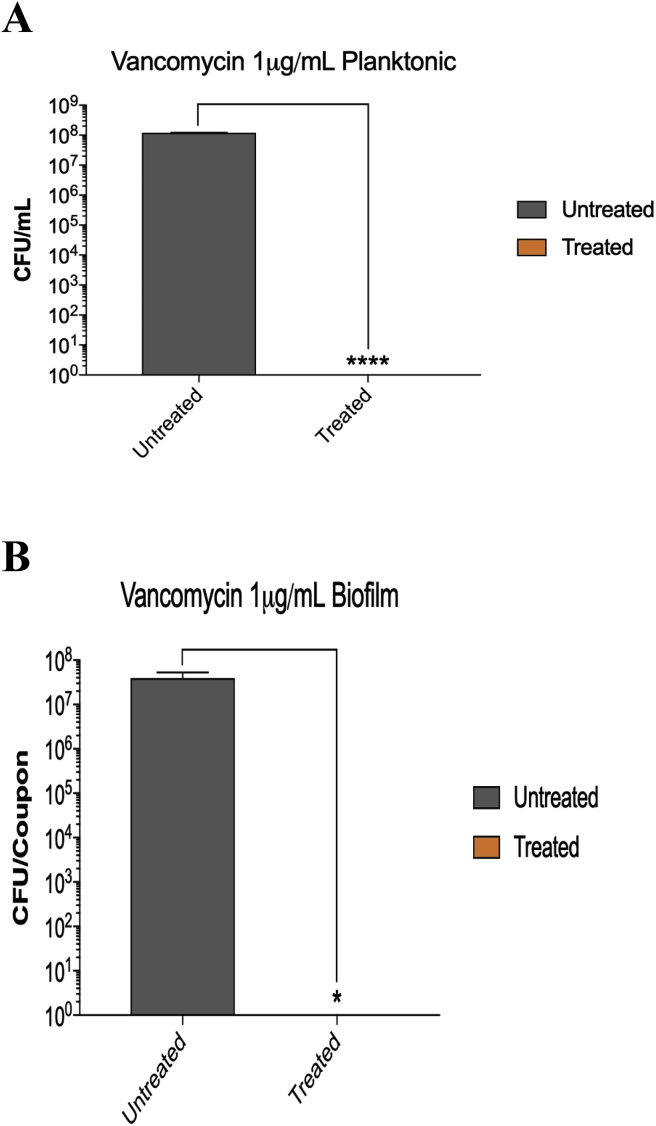

Fig. 3.

A) At 1 μg/ml, Vancomycin inhibited the planktonic growth of S. aureus. Vancomycin was added (at different concentrations) at the time of bacterial inoculation (0-time). After 24 h of incubation at 37 °C, the cultures were serially diluted (10 fold) and aliquots of each dilution were spotted on LB plates to determine the number of microorganisms (colony forming unit [CFU]/ml). B) At 1 μg/ml, Vancomycin inhibited the development of S. aureus biofilm on the stainless steel orthopedic coupons (MBIC). The biofilms were developed using the microtiter plate assay as described in Materials & Methods. Vancomycin was added (at different concentrations) at the time of bacterial inoculation (0-time). After 24 h of incubation at 37 °C, the coupons were removed, rinsed, vortexed, and the number of bacteria (colony forming units [CFU]) within the biofilm was determined. Values represent the average of three independent experiments + SEM.

Fig. 2.

Biofilm formed by the S. aureus strain AH133 which carries a plasmid that codes for the green fluorescent protein on the stainless steel orthopedics coupons. The biofilm was developed as described in Materials and Methods and visualized by confocal laser scanning microscopy.

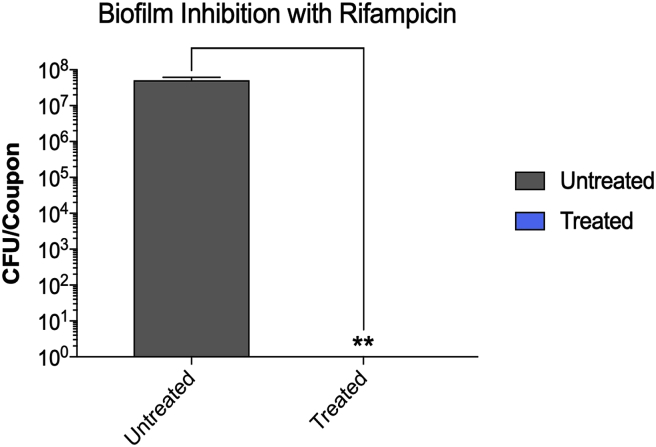

Fig. 5.

At 80 ng/ml, Rifampicin inhibited the development of S. aureus biofilm on the stainless steel orthopedic coupons (MBIC). The biofilms were developed using the microtiter plate assay as described in Materials & Methods. Rifampicin was added (at different concentrations) at the time of bacterial inoculation (0-time). After 24 h of incubation at 37 °C, the coupons were removed, rinsed, vortexed, and the number of bacteria (colony forming units [CFU]) within the biofilm was determined. Values represent the average of three independent experiments + SEM.

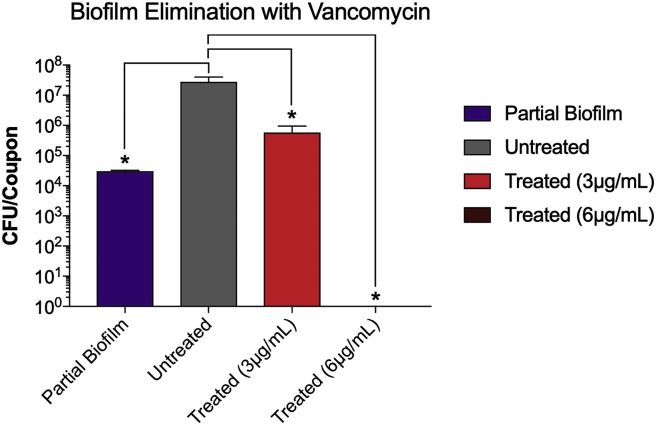

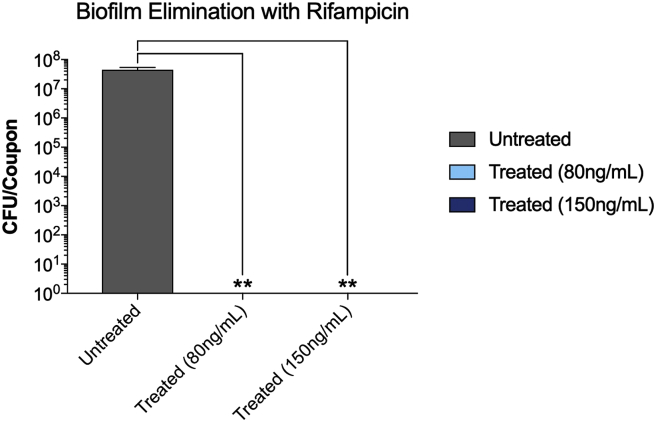

Both antibiotics were effective in eliminating already established S. aureus partial biofilms (MBEC). The antibiotics also vary in their effectiveness in eliminating the biofilms. While the MBEC of Rifampicin was 80 ng/ml, that of Vancomycin was 6 mg/ml (Fig. 4, Fig. 6). The increase in the Vancomycin concentration from 1 (MBIC) to 6 mg/ml (MBEC) is expected (Fig. 4). At 6 mg/ml, Vancomycin completely eliminated the biofilm (Fig. 4). More surprising is that at 80 ng/ml, rifampicin inhibited biofilm development and eliminated a developed biofilm (Fig. 6). These results suggest that both antibiotics are capable of penetrating the biofilm and killing planktonic bacteria within the biofilm. The results also suggest that even at lower doses Rifampicin is very effective in inhibiting as well as eliminating S. aureus biofilms.

Fig. 4.

At 6 μg/ml, Vancomycin eliminated S. aureus partially developed biofilm biofilm on the stainless steel orthopedic coupons (MBEC). The biofilms were developed using the microtiter plate assay as described in Materials & Methods. Partial biofilms were developed for 4 h. After that, the wells of the microtiter plate were divided into three sets; one set was incubated for additional 24 h (untreated), another set was treated with 3 mg/ml of vancomycin and incubated for additional 24 h (treated, 3 μg/ml), and another set was treated with 6 mg/ml of vancomycin and incubated for additional 24 h (treated, 6 μg/ml). Values represent the average of three independent experiments + SEM.

Fig. 6.

At 80 and 150 ng/ml, Rifampicin eliminated S. aureus partially developed biofilm on the stainless steel orthopedic coupons (MBEC). The biofilms were developed using the microtiter plate assay as described in Materials & Methods. Partial biofilms were developed for 4 h. After that, the wells of the microtiter plate were divided into three sets; one set was incubated for additional 24 h (untreated), another set was treated with 80 ng/ml of Rifampicin and incubated for additional 24 h (treated, 80 ng/ml), and another set was treated with 150 ng/ml of Rifampicin and incubated for additional 24 h (treated, 150 ng/ml). Values represent the average of three independent experiments + SEM.

4. Discussion

Despite advances in our understanding of microbiology, infections remain a costly and morbid complication of medical procedures. The formation of biofilm on medically implanted devices has particularly proven to be a significant issue as systemic antibiotics alone are often insufficient in treating these infections.7 In this light, scientific investigators have recently partnered with implant companies and turned their attention to local delivery of antibiotic material at the source of the infection.8, 9, 10 Studies examining the effectiveness of different classes of antibiotics have had varying degrees of success, though many are noting the particular success of rifampin in the treatment S. aureus biofilm11,12.

Rifampin disrupts bacterial DNA transcription by inhibiting the beta subunit of bacterial RNA polymerase, a mechanism that may be bactericidal or bacteriostatic depending on the susceptibility of the specific strain of bacteria and specific concentration of the drug. For this reason, rifampin has been historically paired with other bactericidal antibiotics for a more synergistic effect to help lower the concentrations of antibiotics administered to reach the desired efficacy; typically, a cell-wall inhibitor or an aminoglycoside is used. Both powdered rifampin and vancomycin are both inexpensive and readily available in most hospital pharmacies, making them ideal for use in clinical situations and therefore the two antibiotics chosen for investigation in our study. Furthermore, the work done by Patel et al. has demonstrated that rifampin resistance amongst Staphylococcus species occurs at a very low frequency, making it all the more ideal for clinical use13.

Our study introduces an in vitro model that is reliable to study biofilm on the surface of stainless steel. S. aureus grows remarkably well, creating well-formed multilayered biofilm in a short time as visualized by fluorescence microscopy. Furthermore, this demonstrates that biofilms are readily quantifiable in this model with a colony-forming unit assay, a model that is quickly reproduced in the laboratory. We discovered that after 8 h of growth, the number of bacteria in biofilm approach the number in the initial inoculate. After 24 h of incubation, it is possible to grow over ten million viable bacteria in biofilm on the surface of each plate (measuring 1 square centimeter). Interestingly, the timeline can be thought to emulate an early-onset operating room-acquired infection and demonstrate that these bacteria grow rapidly on the surface of the material.

Having established our model, our group demonstrated that the addition of rifampin and vancomycin powder, alone and in unison, both inhibits the formation of biofilm and eliminates biofilm already present on stainless steel mediums; no viable bacteria were recovered from implant material after incubation with 80 ng/mL rifampin (p = 0.008) or 1 μg/mL vancomycin (p = 0.04). These findings suggest that irrigation with a solution of vancomycin and rifampin could not only be used to inhibit biofilm at the time of initial placement of the medical implant, but potentially be used to eliminate bacteria from an infected implant after it has already been implanted in a patient. Further studies to examine local efficacy of this solution are needed and an animal model would be the next trial. We would expect the outcomes to be favorable with a low side effect profile given the local administration of the antibiotics as opposed to systemic use.

There have been extensive studies evaluating the efficacy of various antibiotic combinations and concentrations against various microbial biofilm formations. While various combinations have been shown to be more effective than others, one common finding in these studies is that rifampin is particularly effective in disrupting the formation of biofilm. However, both in vivo and in vitro trials have varied in their MBICs and optimal timing of application of rifampin solution to optimize biofilm eradication. One of the largest published studies performed by Saginur et al. examined numerous combinations and concentrations of antibiotics against the biofilms of MRSA, MSSA and Staphylococcus epidermidis14. They discovered that rifampin, vancomycin and fusidic acid solutions were the most effective at combating all three biofilm colonies. Specifically, a combination of rifampin and vancomycin was effective at eliminating >90% of MSSA and S. epidermidis colonies after a 24 h inoculation period. Not only does our study confirm the results of the work of Saginur et al., it also suggests that subjecting these biofilms to the provided antibiotic solution within a 24-h period (intraoperatively at time of definitive implant osteosynthesis) is a much more effective method at preventing infection with biofilm-forming microbes. This idea is further supported by a recent study performed by Post et al. wherein they discovered that vancomycin solution dose required to eliminate a mature, 7-day s. aureus biofilm was significantly higher than that required in our experiment (200μg/mL v 6 μg/mL)15. Their biofilm was allowed to mature over a week prior to treatment and required 28 days to eradication; ours was matured 4 h and required only overnight treatment for eradication. Conclusions to arrive when comparing our study to Post et al. is that vancomycin would be best used in combination with rifampin and early treatment of biofilm with these solutions is superior when using only a single antibiotic regimen and delaying treatment.

We do recognize limitations of our study. First, as an in vitro model, it cannot be directly correlated to clinical scenarios; an in vivo model would be more appropriate and thus would be our next focus of study. Another limitation of this work is that only one laboratory strain of methicillin-sensitive S. aureus was studied. The characteristics and biochemistry of S. aureus biofilm are not the same to those of other biofilm-producing microbes that are known to cause implant infections; specifically, those of Staphylococcus epidermidis and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Future studies could examine antibiotic combinations in these microbes to help aid in our understanding. Finally, while rifampin monotherapy was very successful in our model to prevent and eliminate biofilm, it may not do so in vivo.

5. Conclusion

The results of this study suggest that vancomycin and rifampin reliably and predictably inhibit S. aureus biofilm formation on prosthetic material. We envision that similar concentrations of these antibiotics found to be inhibitory in vitro may be applied in situ during implantation of orthopedic devices, and even possibly during irrigation and debridement of implants known to be infected with S. aureus. Future in vivo studies and studies examining soluble antibiotic efficacy against other biofilm species would prove to beneficial in furthering our understanding of these prosthetic infections and how best to proceed with treatment.

Authorship and roles

Christian Douthit, MD – Conceptualization, formal analysis, project administration;

Brent Gudenkauf, BA – Data curation, formal analysis;

Abdul Hamood, PhD – Methodology, project administration;

Nithya Mudaliar, MS - Data curation, formal analysis;

Cyrus Caroom, MD – Funding acquisition, project administration;

Mark Jenkins, MD – Funding acquisition, project administration.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Medical Implants Market by Type (Orthopedic Implants, Cardiac Implants, Stents, Spinal Implants, Neurostimulators, Dental Implants, Breast Implants, Facial Implants) and by Materials (Metallic, Ceramic, Polymers, Natural) - Global Opportunity Analysis and Industry Forecast, 2014 - 2022. Allied Market Research; Aug. 2016. www.alliedmarketresearch.com/medical-implants-market [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bryers J.D. Medical biofilms. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2008 May 1;100(1):1–18. doi: 10.1002/bit.21838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McConoughey S.J. Biofilms in periprosthetic orthopedic infections. Future Microbiol. 2014;9(8):987–1007. doi: 10.2217/fmb.14.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chung P.Y. Anti-biofilm agents: recent breakthrough against multi-drug resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Pathog Dis. 1 April 2014;70(3):231–239. doi: 10.1111/2049-632X.12141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dunne W.M. Diffusion of rifampin and vancomycin through a Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilm. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. December 1993;37(12):2522–2526. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.12.2522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wenke J.C. Rifamycin derivatives are effective against staphylococcal biofilms in vitro and elutable from PMMA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. September 2015;473(9):2874–2884. doi: 10.1007/s11999-015-4300-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akgün D. Outcome of hip and knee periprosthetic joint infections caused by pathogens resistant to biofilm-active antibiotics: results from a prospective cohort study. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. May 2018;138(5):635–642. doi: 10.1007/s00402-018-2886-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butini M.E. In vitro anti-biofilm activity of a biphasic gentamicin-loaded calcium sulfate/hydroxyapatite bone graft substituts. Colloids Surfaces B Biointerfaces. 2018 January;161(1):252–260. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2017.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zarique Z. Current review—the rise of bacteriophage as a unique therapeutic platform in treating peri-prosthetic joint infections. J Orthop Res. 2018 April;36(4):1051–1060. doi: 10.1002/jor.23755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shiels S.M. Determining potential of PMMA as a depot for rifampin to treat recalcitrant orthopaedic infections. Injury. 2017 October;48(10):2095–2100. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2017.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zimmerli W. Orthopaedic biofilm infections. APMIS. 2017 April;125(4):353–364. doi: 10.1111/apm.12687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenberg E.P. Quorum sensing in Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. J Bacteriol. 2004 March;186(6):1838–1850. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.6.1838-1850.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lowry F.D. Synergy of combinations of vancomycin, gentamycin, and rifampin against methicillin-resistant, coagulate-negative staphylococcus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1983 June;23(6):932–934. doi: 10.1128/aac.23.6.932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sagunir R. Multiple combination bactericidal testing of staphylococcal biofilms from implant-associated infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006 Jan;50(1):55–61. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.1.55-61.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Post V. Vancomycin displays time-dependent eradication of mature Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. J Orthop Res. 2017 Feb;35(2):381–388. doi: 10.1002/jor.23291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]