Abstract

Introduction: Transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) is known as standard chondrogenic differentiation agent, even though it comes with undesirable side effects such as early hypertrophic maturation, mineralization, and secretion of inflammatory/angiogenic factors. On the other hand, platelet-rich plasma (PRP) is found to have a chondrogenic impact on mesenchymal stem cell proliferation and differentiation, with no considerable side effects. Therefore, we compared chondrogenic impact of TGF-β and PRP on adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs), to see if PRP could be introduced as an alternative to TGF-β.

Methods: Differentiation of ADSCs was monitored using a couple of methods including glycosaminoglycan production, miRNAs expression, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)/tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) secretion, alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and calcium content assays.

Results: Accordingly, the treatment of differentiating cells with 5% (v/v) PRP resulted in higher glycosaminoglycan production, enhanced SOX9 transcription, and lowered TNFα and VEGF secretion compared to the control and TGF-β groups. Besides, the application of PRP to the media up-regulated miR-146a and miR-199a in early and late stages of chondrogenesis, respectively.

Conclusion: PRP induces in vitro chondrogenesis, as well as TGF-β with lesser inflammatory and hypertrophic side effects.

Keywords: Calcium deposition, Chondrogenesis, Mesenchymal stem cells, Transforming growth factor-beta, Platelet rich plasma

Introduction

Damaged articular cartilage has a limited capacity for self-healing. Cartilage progenitor cells, embryonic stem cells, and mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs)1 are candidate cells for cartilage regeneration.2 However, despite remarkable progress achieved in enhancing the expression of cartilage-specific factors, current chondrogenic differentiation protocols cannot satisfactorily suppress hypertrophic, angiogenic, and inflammatory responses.3,4 The aforementioned side effects may result in the construction of endo-chondral tissue than hyaline cartilage which then disrupts mechanical characteristics and normal functioning of the neo-tissue that is supposed to be used in tissue engineering.2

Transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) suppresses hypertrophic differentiation.2,5-9 However, the constructed neo-cartilage tissue following the addition of TGF-β to the cultured cells, expresses angiogenic and inflammatory markers.10 Application of alternative chondrogenic agents such as platelet rich-plasma (PRP) to the differentiation media comes up with negligible cartilage-associated pathologic responses in the constructed tissue.11,12

In the current study, chondrogenic impact of PRP was compared with TGF-β, to see if PRP has the potential of being introduced as an alternative to TGF-β. Besides, for having a systemic view of chondrogenesis-related pathways, expression profile of main microRNAs was investigated to monitor any possible change in upstream cascades.

Materials and Methods

Cell isolation, expansion, and characterization

Liposuctioned samples were collected from healthy patients after obtaining their written consent according to the ethics of Stem Cell Technology Research Center (Tehran, Iran). Adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs) were isolated according to a previously published procedure.10 Isolated cells were cultured in DMEM (Gibco, Cat. No. 21885025) supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco, Cat. No. 10270106), 1% pen/strep (Gibco, Cat. No. 15070063), and 1% amphotericin (Gibco, Cat. No. R01510). Cells used for differentiation experiments were collected after 3 to 6 subcultures.

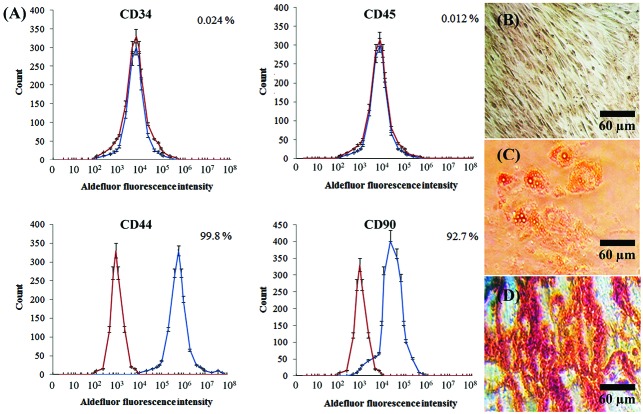

To confirm the multipotent characteristics of the isolated cells, osteogenic and adipogenic differentiations were conducted and then treated cells were stained by Alizarin Red (Fisher Chemical, CAS Number: 130-22-3) and oil Red (Acros Organics, CAS Number: 1320-06-5), respectively. Moreover, expression levels of CD90, CD10, CD34, and CD45 were analyzed by flow cytometry and the histograms were drawn using color codes.

PRP preparation

Blood samples with heparin as anti-coagulant factor centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 10 minutes. Plasma (without the buffy coat) was collected and centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 15 minutes. The sediment of platelets was dissolved in platelet-poor plasma (PPP), and activated using 10% CaCl2 at 4˚C overnight and finally centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 15 minutes. Platelet components (e.g. growth factors, differentiators) that were released via CaCl2 osmotic shock, were pooled in a couple of containers and stored in stocks at -70°C. This extract remained applicable for up to three months. In order to retain PRP concentration at 5% (v/v) in the culture media, the DMEM supplemented with PRP was replaced every two days up to 2 weeks.

Chondrogenic differentiation

The study was performed in three groups of control (no differentiation inducer added), TGF-β (Invitrogen RP8600), and PRP. Next, in each group, 2.5×105 cells were centrifuged (1200 rpm, 5 minutes) to form a pellet. Control medium consisting of proline (400 µg/mL, Sigma P3350000), pyruvate (1 mg/mL, Sigma Cas No.: 127-17-3), ascorbic acid (50 µg/mL, Sigma A92902-25G), and ITS (insulin-transferrin-selenium) 1% (Sigma, I3146) was used for the control group. Standard chondrogenic differentiation medium, which contains TGF-β, included TGF-β 110 ng/mL, dexamethasone 10-7M, proline (400 µg/mL), pyruvate (1 mg/mL), ascorbic acid (50 µg/mL), and ITS 1%. For PRP–based chondrogenic differentiation, DMEM was supplemented with 5% PRP. This procedure repeated exactly for 14 days. PRP concentration of 5% (v/v) was selected for this study since it was reported that proliferation rate of ADSCs was higher in the 2.5%, 5%, and 7.5% PRP groups.13

Alcianblue staining and immunochemical analyses

Samples were prepared with five-micrometer thickness sections and used for immunocytochemistry (ICC) and Alcian blue 8GX (Roth) staining. The immune staining was performed on deparaffinized sections using Col II and X rabbit anti-human antibodies (Abcam, 1:20 and 1:80 dilutions), respectively. Col stands for collagen. The PE-conjugated secondary antibody (eBioscience, 1:80 dilution, goat anti-rabbit) was used for fluorescence visualization. For proteoglycan production assays, sections were stained with Alcian blue 8GX and examined using Genucam digital camera.

Extraction of miRNA and total RNA, cDNA synthesis, and RT Q-PCR

At 14th day of differentiation, total RNA was extracted using RNA extraction kit (CinnaGen, Iran). Then, cDNA was synthesized using cDNA synthesis kit and random hexamers according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Fermentas, Waltham, USA).

The miRNA first-strand cDNA was synthesized according to the manufacturer’s instruction (BONmiR, Iran). Briefly, total RNA was polyadenylated by poly (A) polymerase and reverse transcribed using general RT primer, according to the manufacturer’s protocol (BONmiR, Iran).

Finally, relative fold changes of miRNA expression in PRP and TGF-β groups were normalized against the control group using the comparative CT (2−ΔΔCT) method with U6 small nuclear RNA (snRNA) as an internal control. The primers used in this study are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Sequences of primers used for qRT-PCR .

| H-beta Actin-F | CTT CCT TCC TGG GCA TG |

| H-beta Actin-R | GTC TTT GCG GAT GTC CAC |

| H – SOX9 - F | ATC TGA AGA AGG AGA GCG AG |

| H – SOX9 -R | TCA GAA GTC TCC AGA GCT TG |

| H – COL2A1 - F | GGT CTT GGT GGA AAC TTT GCT |

| H – COL2A1 - R | AAG ACG GCT TCC ACC AGT G |

| H – COLX - F | GAG CGA AAG GCA TCT GTC |

| H – COLX - R | GAA ATC CTC CTG GGA AAA G |

| miR-140-F | ACA GTG GTT TTA GCC TAT GGT |

| miR-145-F | GGT CCA GTT TTT CCA GGA |

| miR-101-F | AGG CTC ATA CAG TAC TGT GAT AAC |

| miR-199-F | TCC TTC CCA GTG TTC AGA CTA |

| miR-146-F | TCC GTG AGA ACT GAA TTC C |

| SNORD47-F | ATC ACT GTA AAA CCG TTC CA |

Monitoring the hypertrophic markers expressions

Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) assay

Samples were lysed with 260 μL lysis buffer (Cell signaling #9803) at the 14th day of chondrogenic differentiation. Samples were then vortexed, sonicated, and incubated with an alkaline buffer solution and a phosphatase substrate solution (Pars Azmun, Iran) at 37°C for 60 minutes. The ALP activity was measured at 405 nm and normalized against total protein content. Protein content was measured using a BSA kit (Life Technologies).

Calcium content assay

Samples for calcium deposition assay were collected 14 days after differentiation initiation, with the same procedure that was performed for alkaline phosphatase assay. Pellets were dissolved in 0.6 N HCl. Amount of deposited calcium was determined using calcium assay kit (Pars Azmun, Iran) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The corresponding absorbance was measured at 550 nm. Results then were normalized against total DNA content.

Measurement of vascular endothelial growth factor and Tumor necrosis factor alpha secretion by ELISA

At the 14th day of differentiation, production of VEGF and TNFα and their release into the culture media were quantified using ELISA. Collected media were used for ELISA assay using mini ELISA development kit (Peprotech). Horseradish peroxidase activity of the antibody detection was assayed using ABTS (2, 2'-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid)) agent at 405 nm. The wavelength of 650 nm was used as the reference wavelength. Since PRP by itself contains considerable amounts of VEGF and TNFα, the supernatant media were replaced with base media (DMEM+1% ITS) in PRP supplemented groups for two days. Then, secreted VEGF/TNFα into the PRP-free base media was measured. Results then were normalized against total protein content.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out by one way ANOVA using Prism software and the differences were regarded as significant if P value was less than 0.05. All experiments repeated at least three times. Data in graphs were shown as mean ± standard deviation (±SD). Images of Alcian blue staining and ICC, acquired from different samples, were quantified using ImageJ software.

Results

In order to study ADSCs differentiation, first, we need to evaluate the stemness of the cells. For this purpose, the expression of hematopoietic stemness markers (CD34 and CD45) and mesenchymal stemness markers (CD44 and CD90) were assessed using flow cytometry. The red and blue peaks stand for control and test, respectively (Fig. 1A). Non-differentiated ADSCs, which did not fate to any mature cell, were considered as control (Fig. 1B). To assure the capability of ADSCs to differentiate, their differentiation to adipose and bone was checked (Figs. 1C & D). In the next step, chondrogenic differentiation was induced in ADSCs using TGF-β and PRP. At last, the expression of chondrocyte specific markers and cartilage-associated markers was monitored.

Fig. 1.

Characterization of isolated cells stemness properties. (A) Hematopoietic markers (CD34, CD45) were not expressed from the cells while mesenchymal stemness markers (CD44 and CD90) were highly expressed. Percentages represent the amount of marker expression. Each point is average of three sets of experiments and error bars represent standard deviation. (B) Non-differentiated ADSCs as control; (C) Adipogenic vesicles were observed by oil Red staining; (D) Calcium deposition was observed after osteogenic differentiation of ADSCs.

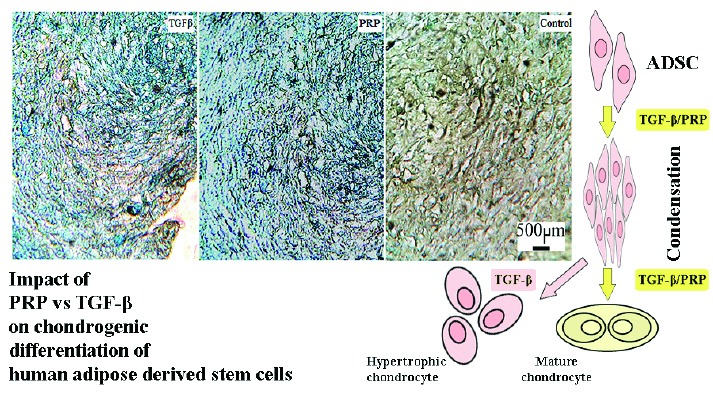

Chondrogenic differentiation assay by glycosaminoglycan (GAG) production

The GAG production in TGF-β and PRP treatments was assigned to the increment of blue color according to the RGB measurement tool of Image J software (Fig. 2). In this regard, the blue color intensity of the control sample (144.88 ± 4.44) significantly increased to 170.17 ± 7.61 and 166.78 ± 7.72 in TGF-β and PRP treatments, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Alcian blue staining of cultured chondrogenic differentiated cells.

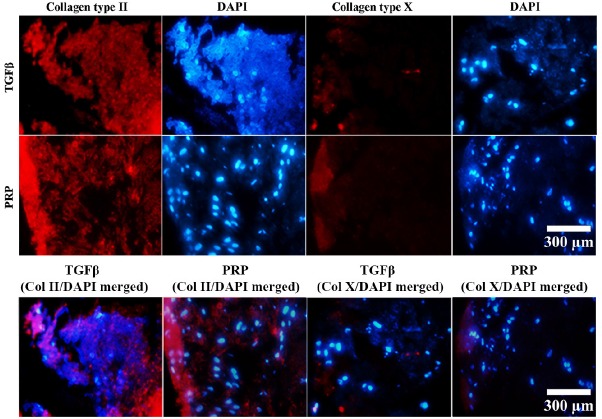

As presented in Fig. 3, Col-II deposition in the extracellular matrix of differentiated pellets was observed in TGF-β and PRP treatments. All samples were simultaneously stained with DAPI (4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) to confirm their vitality. The deposition of Col-X in the extracellular matrix, as a marker of hypertrophic maturation, was also observed for both TGF-β and PRP treatments. The comparative intensity of red color against the background (black color) was measured by RGB analysis tool of ImageJ software. Then, intensity of Col-II and X deposition was normalized to the intensity of DAPI (blue color). In this regard, 91.53 % ± 3.71 of living ADSCs that were treated with TGF-β, deposited Col-II in their extracellular matrix (ECM), while 47.11 % ± 3.08 of them deposited Col-X in their ECM. In the case of cells that were treated with PRP, 98.1 % ± 10.21 of living ADSCs deposited Col-II in their ECM while 47.60 % ± 3.08 of them deposited Col-X in their ECM.

Fig. 3.

Expressions of collagen II and X in chondrogenically differentiated pellets were visualized by PE-immunostaining. From left to right, first and second columns represent immunocytochemistry (ICC) staining for PE-conjugated anti-Col II and their corresponding DAPI stained micrograph, respectively. The third and fourth columns, from left to right, represent immunostaining with PE-conjugated anti-Col X and their corresponding DAPI stained micrograph, respectively.

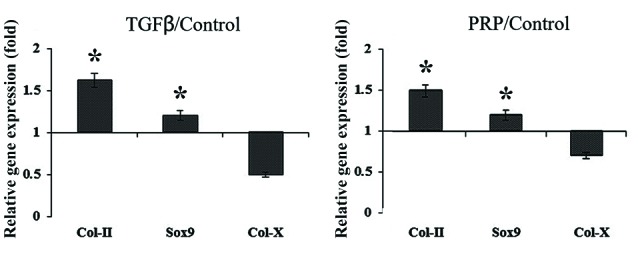

mRNA expression of chondrogenic markers

Normalization of real-time Q-PCR expression in respect to the control showed that application of either TGF-β or PRP to the differentiation media considerably upregulated SOX9 and Col-II while had no significant impact on the expression of Col-X (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Comparative normalized gene expression in chondrogenically differentiated pellets after 14 days. The vertical axis represents relative gene expression, which is normalized against control. Relative quantification is based on the expression levels of SNORD gene. The star on the bar stand for differences with P value less 0.05.

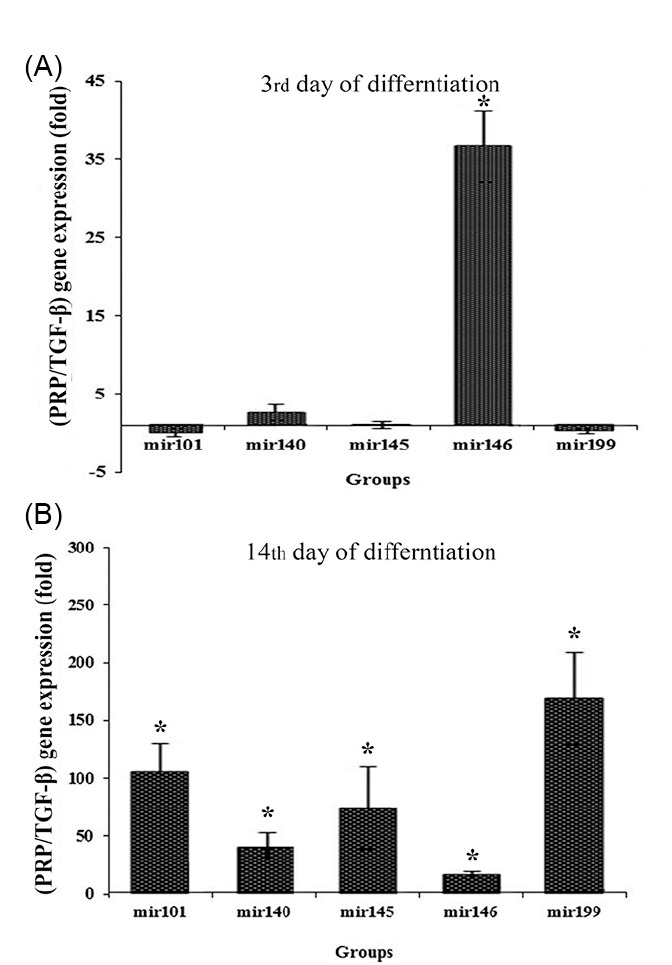

microRNA expression of chondrogenic markers

At 3rd day of differentiation, PRP/TGF-β relative level of miR-146a expression upregulated significantly while PRP/TGF-β relative expression level of other miRNAs remained unchanged (Fig. 5). At 14th day of differentiation, PRP/TGF-β relative level of all five miRNAs upregulated (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Expressions of miRNAs at (A) 3rd and (B) 14th days in chondrogenically differentiated cultures. Relative quantification is based on the expression level of SNORD gene. Present demonstration is based on normalizing PRP gene expression against TGF-β using REST software.

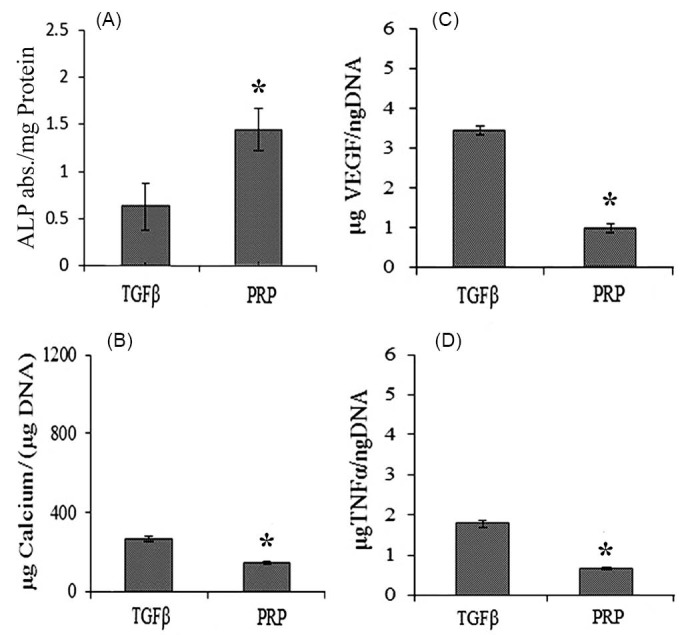

Alkaline phosphatase and calcium content assay

The ALP activity of PRP treatment was considerably higher than that of TGF-β (Fig. 6A). Based on calcium content assay (Fig. 6B), calcium deposition in the PRP group was significantly lower than that in TGF-β.

Fig. 6.

Expressions of angiogenic and inflammatory factors by chondrogenically differentiated cells at 14th day. (A) The alkaline phosphatase (ALP) assay, (B) Calcium deposition assay, (C) Expression profiles of VEGF in different groups, and (D) Expression profile of TNFα. The “*” demonstrate significant difference in respect to TGF-β.

VEGF and TNFα secretion

When ADSCs were treated with PRP, the least VEGF secretion was observed (Fig. 6C). Treatment of ADSCs with TGF-β resulted in higher TNFα secretion compared to the PRP group (Fig. 6D).

Discussion

Improving the effectiveness of the chondrogenic differentiation medium became the focus of many researches in recent years.14 The current chondrogenic differentiation methods may lead to early hypertrophic maturation of the chondrogenically differentiated cells. Mineralization and secretions of inflammatory and angiogenic factors in such cells would lead to the construction of already-ill tissues. Herein, regarding the chondro-promotive effects of PRP, we examined the expression of hypertrophic, angiogenic, and inflammatory markers to see if PRP could be introduced as an alternative to TGF-β in chondrogenic differentiation.

How GAG production, Col II deposition, and Col X expression are affected by our treatments?

The accelerated chondrogenesis is evidenced by an increase in GAG content.15 Treatment of ADSCs with TGF-β and PRP results in considerable GAG production (Fig. 2). Besides, based on the intensity of the deposited Alcian blue stain, one can tell that PRP induces GAG production as well as TGF-β.

During embryogenesis, chondroblasts synthesize collagen type II and proteoglycans while post-mitotic hypertrophic chondrocytes express collagen type X and matrix metalloproteinase.8 Both TGF-β and PRP induce major Col-II deposition in ADSCs’ ECM while inducing moderate Col-X production (Fig. 3), which is in agreement with previous reports.8

What we learn from the gene expression profile?

The SOX9 as a key transcription factor involved in the chondrogenesis inhibits ECM degradation and enhances the chondrogenesis process.16,17 After 14 days (late stage of chondrogenesis), both of chondroprotective markers (Col II and SOX9) significantly upregulated after the application of either TGF-β or PRP to the culture media (Fig. 4). The ICC assay also confirmed that both TGF-β and PRP equally promoted chondrogenesis and ECM stabilization.

What can we learn from variation of miRNA expression profile?

Unlike various transcription factors and cytokines that control multiple phases of chondrogenic differentiation, a few miRNAs intermediate chondrogenic differentiation of stem cells.16 The miR-146 is confirmed to be expressed in osteoarthritis (OA) cartilage in non-physiological conditions which comes up with cartilage lesions, inflammation, and neoangiogenesis.18 In fact, miR-146a and miR-199a promote the degradation of the cartilage matrix.19 At the early stage of chondrogenesis (3rd day), PRP resulted in overexpression of miR-146 compared to TGF-β (Fig. 5), which remained upregulated until late chondrogenesis (14th day).

Early or late co-expression of miR-101 with miR-145 removes suppression of MSC condensation, chondrocytes proliferation, and differentiation.20,21 The miR-140 upregulation is positively correlated with SOX9 overexpression,22 which in turn controls chondrocyte proliferation.23,24 Upregulation of miR-199 promotes degradation of cartilage matrix as well as miR-146.19 The PRP considerably induced upregulation of miR-101, 140, and 145 in late chondrogenesis (14th day), compared to the TGF-β (Fig. 5). Although upregulation of miR-101, 140, and 145 promotes chondroprotective effects and inhibits inflammatory side effects, miR-199 and miR-146 exert anti-chondrogenic roles by targeting SMAD1 and SMAD2/3, respectively.25 Therefore, at early chondrogenesis, PRP stimulates angiogenesis and ECM neogenesis via the upregulation of miR-146 while at late chondrogenesis, facilitates ADSCs differentiation to mature chondrocytes via upregulation of miR-101, 140, and 145, as well as tuning their stemness ability.

What do ALP and calcium deposition assays reveal?

Increment of either alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity or calcium deposition in the ECM results in hypertrophy, matrix degradation, and osteogenesis.8 Although enhanced ALP activity was observed at late chondrogenesis, following the application of PRP over TGF-β (Fig. 6A), calcium deposition eliminated at late chondrogenesis (Fig. 6B).

How the applied treatments affect neovascularization and TNFα secretion?

The presence of PRP in ADSC differentiating media instead of TGF-β for 14 days, considerably suppressed VEGF secretion (Fig. 6C). Hence, PRP guarantees ADSC fate to chondrogenesis rather than ossification.

All of the chondrocytes secret TNFα at the basal level.26 However, the IL-1β boosts TNFα production. TNF‐α mediates both chondrocyte apoptosis and expression of endochondral resorption mediated cytokines. Application of TGF-β triggered secretion of TNFα while the addition of PRP to the media suppressed it (Fig. 6D).

The miR-146a does not target TNFα directly but up-regulation of this miRNA results in the downregulation of stimuli-mediated TNFα.26 Our results are in line with this fact that higher miR-146a expression is accompanied with the diminished secretion of TNFα in PRP groups.

Conclusion

PRP seems to be a suitable alternative to TGF-β to induce in vitro chondrogenesis. The advantages of PRP over TGF-β up to the late stage of chondrogenesis include; higher GAG production, enhanced SOX9 transcription, lowered TNFα and VEGF secretions. PRP stimulates angiogenesis and ECM neogenesis via the upregulation of miR-146 at early chondrogenesis while facilitates ADSCs differentiation to mature chondrocytes at late chondrogenesis, via the upregulation of miR-101, 140, and 145, as well as tuning their stemness ability. Therefore, PRP promotes chondrogenesis of ADSCs as well as TGF-β in in-vitro conditions. Since the preparation of PRP is much easier and less expensive than TGF-β, it could be a perfect alternative to TGF-β in in-vitro chondrogenesis studies.

Funding sources

This work was supported by the Stem Cell Technology Research Center (ISTI grant number: T214427N).

Ethical Statement

Liposuctioned samples were collected from healthy patients after obtaining their written consent according to the ethics of Stem Cell Technology Research Center (Tehran, Iran).

Competing interests

The authors have no commercial, proprietary, or financial interest in the products or companies described in this article.

Authors' contribution

RH: Concept/design/data collection, MiK: Data collection, MaK: Data analysis/interpretation, IR: Drafting article/ statistics, KP: Approval of article, HH: Data collection, RT: Data collection, MS: Critical revision of article, FK: Critical revision of article, SZ: Data collection, and HHA: Concept/design.

Research Highlights

What is the current knowledge?

√ Transforming growth factor (TGF-β) is a standard chondrogenic differentiation agent.

√ TGF-β is very expensive and comes with undesirable side effects during chondrogenesis.

What is new here?

√ PRP is found to have chondrogenic impact on MSC proliferation and differentiation.

√ PRP preparation is easy, fast, and not expensive.

√ PRP does not come with considerable side effects during chondrogenesis.

References

- 1.Rezaei M, Jamshidi S, Saffarpour A, Ashouri M, Rahbarghazi R, Rokn AR. et al. Transplantation of Bone Marrow" Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells, Platelet-Rich Plasma, and Fibrin Glue for Periodontal Regeneration. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2019;39. 1:e32–e45. doi: 10.11607/prd.3691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen S, Fu P, Cong R, Wu H, Pei M. Strategies to minimize hypertrophy in cartilage engineering and regeneration. Genes Dis. 2015;2:76–95. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2014.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramezanifard R, Kabiri M, Ahvaz HH. Effects of platelet rich plasma and chondrocyte co-culture on MSC chondrogenesis, hypertrophy and pathological responses. EXCLI J. 2017;16:1031. doi: 10.17179/excli2017-453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hossein M, Masoud S, Hana H-A, Hossein G, Mojgan B, Seyed EE. et al. New Approach for Differentiation of Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells Toward Chondrocyte Cells With Overexpression of MicroRNA-140. ASAIO J. 2018;64 .5:662–672. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000000688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van der Kraan PM, Blaney Davidson EN, Blom A, van den Berg WB. TGF-beta signaling in chondrocyte terminal differentiation and osteoarthritis: Modulation and integration of signaling pathways through receptor-Smads. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2009;17:1539–45. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mueller MB, Tuan RS. Functional characterization of hypertrophy in chondrogenesis of human mesenchymal stem cells. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:1377–88. doi: 10.1002/art.23370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mueller MB, Fischer M, Zellner J, Berner A, Dienstknecht T, Prantl L. et al. Hypertrophy in mesenchymal stem cell chondrogenesis: effect of TGF-β isoforms and chondrogenic conditioning. Cells Tissues Organs. 2010;192:158–66. doi: 10.1159/000313399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dexheimer V, Gabler J, Bomans K, Sims T, Omlor G, Richter W. Differential expression of TGF-β superfamily members and role of Smad1/5/9-signalling in chondral versus endochondral chondrocyte differentiation. Sci Rep. 2016;6:36655. doi: 10.1038/srep36655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahboudi H, Soleimani M, Enderami SE, Kehtari M, Hanaee-Ahvaz H, Ghanbarian H. et al. The effect of nanofibre-based polyethersulfone (PES) scaffold on the chondrogenesis of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2018;46. 8:1948–1956. doi: 10.1080/21691401.2017.1396998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pakfar A, Irani S, Hanaee-Ahvaz H. Expressions of pathologic markers in PRP based chondrogenic differentiation of human adipose derived stem cells. Tissue Cell. 2017;49 .1:122–130. doi: 10.1016/j.tice.2016.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andia I, Maffulli N. Platelet-rich plasma for managing pain and inflammation in osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2013;9 .12:721–30. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2013.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xie X, Zhang C, Tuan RS. Biology of platelet-rich plasma and its clinical application in cartilage repair. Arthritis Res Ther. 2014;16 .1:204. doi: 10.1186/ar4493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen C-F, Liao H-T. Platelet-rich plasma enhances adipose-derived stem cell-mediated angiogenesis in a mouse ischemic hindlimb model. World J Stem Cells. 2018;10:212. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v10.i12.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ruiz M, Maumus M, Jorgensen C, Noël D. A Roadmap to Non-Hematopoietic Stem Cell-based Therapeutics: Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Based Therapy of Osteoarthritis: Current Clinical Developments and Future Therapeutic Strategies. Elsevier; 2019. p. 87-109. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-811920-4.00005-7.

- 15.Ciombor DM, Lester G, Aaron RK, Neame P, Caterson B. Low frequency EMF regulates chondrocyte differentiation and expression of matrix proteins. J Orthop Res. 2002;20:40–50. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(01)00071-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu C, Tian B, Qu X, Liu F, Tang T, Qin A. et al. MicroRNAs play a role in chondrogenesis and osteoarthritis (review) Int J Mol Med. 2014;34:13–23. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2014.1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dai L, Zhang X, Hu X, Zhou C, Ao Y. Silencing of microRNA-101 prevents IL-1beta-induced extracellular matrix degradation in chondrocytes. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14:R268. doi: 10.1186/ar4114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li J, Huang J, Dai L, Yu D, Chen Q, Zhang X. et al. miR-146a, an IL-1β responsive miRNA, induces vascular endothelial growth factor and chondrocyte apoptosis by targeting Smad4. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14:R75. doi: 10.1186/ar3798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu X-M, Meng H-Y, Yuan X-L, Wang Y, Guo Q-Y, Peng J. et al. MicroRNAs&#x 2019; Involvement in Osteoarthritis and the Prospects for Treatments. J Evid Based Integr Med. 2015;2015:13. doi: 10.1155/2015/236179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mayer‐Wagner S, Passberger A, Sievers B, Aigner J, Summer B, Schiergens TS. et al. Effects of low frequency electromagnetic fields on the chondrogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. Bioelectromagnetics. 2011;32:283–90. doi: 10.1002/bem.20633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gurusinghe S, Strappe P. Gene Modification of Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Articular Chondrocytes to Enhance Chondrogenesis. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:10. doi: 10.1155/2014/369528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang X, Chang A, Li Y, Gao Y, Wang H, Ma Z. et al. miR-140-5p regulates adipocyte differentiation by targeting transforming growth factor-β signaling. Sci Rep. 2015;5:18118. doi: 10.1038/srep18118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karlsen TA, Jakobsen RB, Mikkelsen TS, Brinchmann JE. microRNA-140 targets RALA and regulates chondrogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells by translational enhancement of SOX9 and ACAN. Stem Cells Dev. 2014;23:290–304. doi: 10.1089/scd.2013.0209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang J, Qin S, Yi C, Ma G, Zhu H, Zhou W. et al. MiR-140 is co-expressed with Wwp2-C transcript and activated by Sox9 to target Sp1 in maintaining the chondrocyte proliferation. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:2992–7. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lolli A, Colella F, De Bari C, van Osch GJ. Targeting anti‐chondrogenic factors for the stimulation of chondrogenesis: A new paradigm in cartilage repair. J Orthop Res. 2019;37 .1:12–22. doi: 10.1002/jor.24136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones SW, Watkins G, Le Good N, Roberts S, Murphy CL, Brockbank SMV. et al. The identification of differentially expressed microRNA in osteoarthritic tissue that modulate the production of TNF-α and MMP13. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2009;17:464–72. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]