Dear Editor,

Neurodevelopmental disorders include a wide range of conditions such as epilepsy, intellectual disability, and autism spectrum disorder. These disorders commonly co-occur in patients, which suggests that they share a common etiology [1, 2]. Genetic advances resulting from sequencing techniques over the past few years have greatly expanded our understanding of neurodevelopmental disorders. Numerous specific genes have been identified in patients with neurodevelopmental disorders that have pedigrees with Mendelian inheritance [3]. However, the majority of patients with neurodevelopmental disorders of possible genetic causes remain without specific diagnoses. The clinical heterogeneity and low incidence rate of these undefined disorders present a challenge for determining genetic diagnoses. Recently, using an unbiased genotype-driven approach, the United Kingdom Deciphering Developmental Disorders project has identified a total of 12 novel genes that have been suggested to be associated with developmental disorders [4]. In particular, de novo pathogenic variants in PPP2R5D (OMIM#601646) and PPP2R1A (OMIM#605983) were found for the first time to be involved in phenotypically similar patients with putatively novel neurodevelopmental disorders. More recently, these findings have been further confirmed in additional patients with intellectual disabilities [5]. In the present study, we report a de novo variant in the PPP2R1A gene as a likely pathogenic variant in an infant patient who manifested neurodevelopmental abnormalities.

The patient, a 9-month-old male, was the second child of non-consanguineous parents who had no previous family history of neurodevelopmental disorders. The infant was conceived by in vitro fertilization and was born by cesarean-section delivery following a full-term pregnancy. His mother and father were 24 and 27 years old, respectively. No abnormalities were noted during pregnancy. The infant had a birth weight of 3.4 kg, a head circumference of 33 cm, and a body length of 49 cm. Birth asphyxia and dysmorphia of external organs were not reported. A description of frequent milk-vomiting was recalled by his mother during times of breast-feeding. The infant was able to smile at 1 month, raise his head at 3 months, and sit at 6 months. At 6 months of age, the infant experienced his first seizure, during which he exhibited an ocular gaze in both eyes and had a clonic convulsion of the extremities for approximately 2 min. Subsequently, seizures occurred several times during hospitalization. Levetiracetam was administered and was successful at controlling subsequent seizures. A physical examination showed that the patient had a weight of 6.0 kg (< 3rd percentile), a head circumference of 42 cm (15th percentile), and a height of 65 cm (10th percentile). At 9 months of age, a neurological examination showed that he could sit with slight assistance and was capable of receiving and understanding simple instructions from adults. No other neurological abnormalities were found.

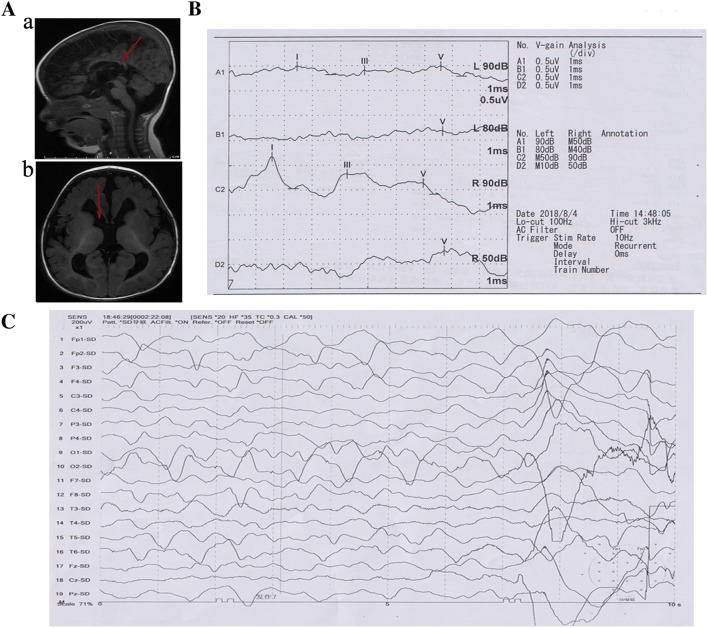

Magnetic resonance imaging revealed a reduction of brain parenchyma, widening of the cerebral sulci and fissures, enlargement of the ventricular system, and agenesis of the corpus callosum (Fig. 1A). Brainstem auditory evoked potentials suggested peripheral and central impairment of the auditory pathways and increased auditory brainstem response thresholds (Fig. 1B). Video electroencephalography (EEG) monitored a focal seizure and recorded synchronous discharges of high-amplitude δ-waves spreading from the frontal lobe to the entire brain (Fig. 1C). No abnormalities were found in laboratory tests. No other abnormalities—including dysmorphic features or complications of the heart, kidney, or liver—were found.

Fig. 1.

Clinical and genetic data of the patient. A Brain MRI showing agenesis of the corpus callosum (a), enlargement of the ventricular system, and retardation of myelination of the white matter (b). B Brainstem auditory evoked potentials showing that the I, III, and V waves were hardly detectable and the latency to each wave was prolonged on the left side; the waveform of the V wave was poorly differentiated with a normal range of latency to each wave on the right side; the auditory brainstem response thresholds were increased. C EEG demonstrating synchronous discharges of high-amplitude δ-waves spreading from the frontal lobe.

Karyotyping based on low-coverage genome-sequencing did not detect possible causative copy-number variants in the patient. An average sequence depth of 100× was achieved and > 90% of the target exome was captured at 20× coverage or higher for each sample via whole-exome sequencing (WES). Sequencing data were processed by a computational pipeline for WES data processing and analysis, following a previously-described workflow [6]. We found a de novo variant (chr19:52716212, NM_014225.5, c.656C>T, p.S219L) in PPP2R1A, a disease-associated gene previously classified as likely to be pathogenic according to the guidelines of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics [7]. In addition, this variant has been identified as a likely pathogenic variant in a patient with epilepsy and intellectual disability [8], which is useful information for further assessing its potential pathogenicity.

Protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) is a heterodimeric core enzyme [9], which comprises a scaffolding subunit (A), a catalytic subunit (C), and a specific substrate-binding regulatory subunit (B) that regulates substrate specificity, cellular localization, and enzymatic activity. The scaffolding A subunit (also called PR65) and regulatory B subunit are encoded by the PPP2R1A and PPP2R5D genes, respectively. De novo missense pathogenic variants of PPP2R5D [MRD35 (OMIM#616355)] and PPP2R1A [MRD36 (OMIM#616362)] have been reported to cause autosomal-dominant mental retardation [5].

Patients with MRD36 were more severely affected than patients with MRD35 in terms of mental retardation [5], which is consistent with the vital function of active PP2A holoenzymes in biogenesis. Patients with MRD36 were characterized as having severely delayed psychomotor development, agenesis of the corpus callosum, enlarged ventricles, and possible facial dysmorphism. In the present study, although our patient presented roughly normal developmental milestones in early infancy, the imaging findings of the infant’s brain morphology and epileptic signatures in the EEG were in accord with the infant’s reported symptoms. Furthermore, sensorineural hearing loss and delayed myelination in the white matter might be a unique feature of our patient, which suggests clinical heterogeneity among patients with PPP2R1A variants. The infant reported in the present study should be followed up to document any other emerging phenotypes.

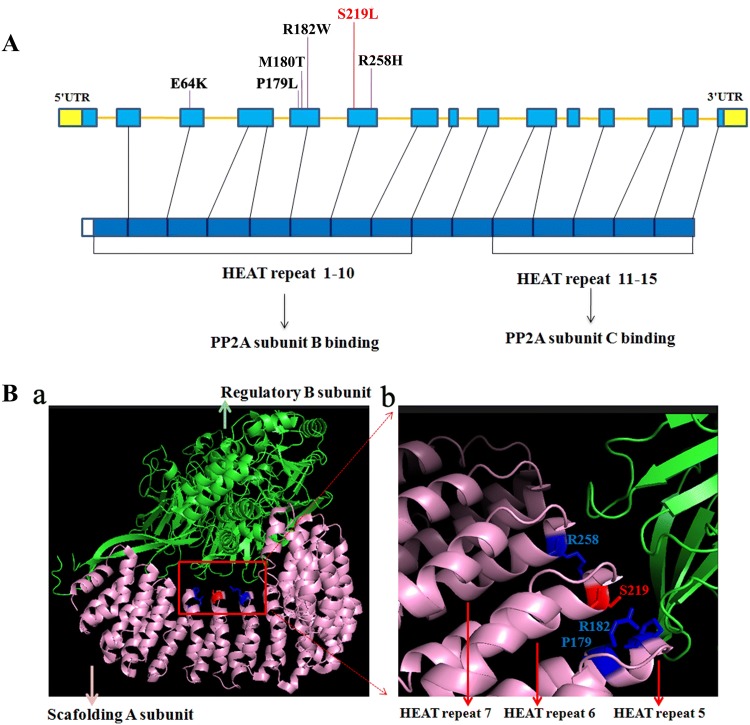

To date, only six variants in the PPP2R1A gene have been reported in patients with mental retardation (Fig. 2A), and all six were de novo in sporadic patients. Interestingly, the reported positions—P179, R182, and R258—have also been documented as hotspots in malignancies [10]. These findings indicate that PPP2R1A has a high spontaneous mutation rate. Regional variant rates are subject to a variety of intrinsic characteristics and extrinsic factors [11]. Several factors (e.g., CpG sites, DNase hypersensitivity, and high GC content) may explain the high regional variant rates in this gene.

Fig. 2.

Pathogenic variant of PPP2R1A and its protein structure. A The six reported variants (E64K [12], P179L [4], M180T [13], R182W [4], S219L, and R258H [5]) and their relative locations in the causative gene and its encoded protein. We report a likely pathogenic variant at S219 (red). B (a) Structure of PPP2R1A interacting with the regulatory B subunit. (b) Enlargement showing the causative amino-acids located in the center of this interaction.

The PPP2R1A is composed of 15 HEAT (huntingtin, elongation factor 3, protein phosphatase 2A, and yeast kinase TOR1) repeat motifs, of which HEATs 1–8 mediate interactions with a specific regulatory B subunit [9]. The reported causative variants in previous studies are located in HEAT domains 5 and 7 of PPP2R1A. The variant in our present study was positioned in the sixth HEAT motif. The amino-acids of these variants are closely linked with the B subunit of the PP2A complex. Taken together, these findings suggest that these sites may be critical for interactions with other subunits and that mutants may exhibit altered interactions among subunits (Fig. 2B).

In summary, we report a novel de novo variant in the PPP2R1A gene as a likely pathogenic variant. Although rare, this PPP2R1A variant-induced condition should be considered in patients with unknown neurodevelopmental abnormalities, especially if such patients have agenesis of the corpus callosum. At present, a variant-driven approach to unrecognized disorders may be an effective strategy for determining the etiology of potential genetic disorders.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Department of Hunan Province, China (2017JJ3142).

Conflict of interest

The authors claim no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Srivastava AK, Schwartz CE. Intellectual disability and autism spectrum disorders: causal genes and molecular mechanisms. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014;46(Pt 2):161–174. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xu M, Ji Y, Zhang T, Jiang X, Fan Y, Geng J, et al. Clinical application of chromosome microarray analysis in Han Chinese children with neurodevelopmental disorders. Neurosci Bull. 2018;34:981–991. doi: 10.1007/s12264-018-0238-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vissers LE, Gilissen C, Veltman JA. Genetic studies in intellectual disability and related disorders. Nat Rev Genet. 2016;17:9–18. doi: 10.1038/nrg3999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fitzgerald TW, Gerety SS, Jones WD, Kogelenberg MV, King DA, McRae J, et al. Large-scale discovery of novel genetic causes of developmental disorders. Nature 2015, 519: 223–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Houge G, Haesen D, Vissers LE, Mehta S, Parker MJ, Wright M, et al. B56δ-related protein phosphatase 2A dysfunction identified in patients with intellectual disability. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:3051–3062. doi: 10.1172/JCI79860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang JL, Cao L, Li XH, Hu ZM, Li JD, Zhang JG, et al. Identification of PRRT2 as the causative gene of paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesias. Brain. 2011;134:3490–3498. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17:405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamdan FF, Myers CT, Cossette P, Lemay P, Spiegelman D, Laporte AD, et al. High rate of recurrent de novo mutations in developmental and epileptic encephalopathies. Am J Hum Genet. 2017;101:664–685. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cho US, Xu W. Crystal structure of a protein phosphatase 2A heterotrimeric holoenzyme. Nature. 2007;445:53–57. doi: 10.1038/nature05351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McConechy MK, Anglesio MS, Kalloger SE, Yang W, Senz J, Chow C, et al. Subtype-specific mutation of PPP2R1A in endometrial and ovarian carcinomas. J Pathol. 2011;223:567–573. doi: 10.1002/path.2848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ségurel L, Wyman MJ, Przeworski M. Determinants of mutation rate variation in the human germline. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2014;15:47–70. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-031714-125740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anazi S, Maddirevula S, Salpietro V, Asi YT, Alsahli S, Alhashem A, et al. Expanding the genetic heterogeneity of intellectual disability. Hum Genet. 2017;136:1419–1429. doi: 10.1007/s00439-017-1843-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lelieveld SH, Wiel L, Venselaar H, Pfundt R, Vriend G, Veltman JA, et al. Spatial clustering of de novo missense mutations identifies candidate neurodevelopmental disorder-associated genes. Am J Hum Genet. 2017;101:478–484. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]