Abstract

Bioinspired assemblies bear massive potential for energy generation and storage. Yet, biological molecules have severe limitations for charge transfer. Here, we report l-tryptophan-d-tryptophan assembling architectures comprising alternating water and peptide layers. The extensive connection of water molecules results in significant dipole–dipole interactions and piezoelectric response that can be further engineered by doping via iodine adsorption or isotope replacement with no change in the chemical composition. This simple system and the new doping strategies supply alternative solutions for enhancing charge transfer in bioinspired supramolecular architectures.

Peptide assemblies exhibit flexible supramolecular morphologies1–3 with diverse physicochemical properties, such as semiconductivity, piezoelectricity and ferroelectricity.4–6 However, due to the inherently low dielectric constant, energy translocation through peptide architectures is inefficient, which severely hinders their practical application.7 Incorporation of water molecules can improve the conductivity of bioinspired supramolecular structures,8 thus prompting the search for peptide building blocks that can template long-range hydrogen-bonded internal water molecule networks.9 Another way to improve charge transfer inside peptide assemblies is by the utilization of doping, such as through chemical conjugation or co-assembly with functional moieties.10 However, commonly-applied doping strategies generally alter the molecular structures or self-assembly mechanism, resulting in uncontrollable changes in the peptide supramolecular structures.11

Here, we report the design of a simple aromatic dipeptide, l-tryptophan-d-tryptophan (Ww). We show the Ww dipeptide to form needle-like crystals (Fig. 1a) that are monoclinic in symmetry (Cif. S1, ESI†),9 with the length and width aligned along the b and c direction, respectively (Fig. 1b). Intriguingly, a large population of ordered water molecules was present in the crystal, with four water molecules, marked as ①–④, connected to each peptide monomer through hydrogen bonds (Fig. 1c).9 Correspondingly, the crystal was comprised of alternating peptide and water molecule domains (Fig. 1d, middle panel). The hydrogen bonding network formed two circular channels with the peptide backbones along the b direction (Fig. 1d, subpanel “1” and “2”). Specifically, the wider channel was formed by the amino group and one of the carboxylic oxygen atoms from the peptide backbone along with four water molecules positioned in a sequence of NH3+–①–②–④–③–COO− which formed hydrogen bonds 2.89 Å (Namino…O①), 2.79 Å (O①…O②), 2.71 Å (O②…O④), 2.79 Å (O③…O④) and 2.76 Å (O③…Ocarboxylic) in length (Fig. 1d, marked with green dashed lines). The narrower channel was formed by the amino group and the same carboxylic oxygen atom with two water molecules in a sequence of NH3+–③–④–COO− forming hydrogen bonds of 2.70 Å (Namino…O③), 2.79 Å (O③…O④) and 2.66 Å (O④…Ocarboxylic) (Fig. 1d, subpanel “1”, marked with magenta dashed lines). The remaining hydrogen bonds provided structural support and interconnectivity, including those between the amino group and water ② (Namino…O②; 2.86 Å), water ② and the amide oxygen (O②…Oamide; 2.76 Å), and water ④ and the other carboxylic oxygen atom (O④…Ocarboxylic; 2.80 Å) (Fig. 1d, subpanel “1”, marked with blue dashed lines). The adjacent channels were connected to each other through the protrusion of water ① along the a direction (Fig. 1d, subpanel “2”), thereby generating an extensive hydrogen bonding network with a long-range sequence of ③–④–②–①–②–④–③ water molecules (Fig. 1d, subpanel “3”). The ①–③ water molecules lined up in the ab plane, leaving the two ④ water molecules distributed at the two sides to connect the peptides through a hydrogen bond of 2.80 Å (O④…Ocarboxylic) (Fig. 1d, subpanel “4”), thus completing the “sandwich”-like architecture. Away from the highly hydrated hydrogen bonding networks, the side-chain indole rings organized into hydrophobic regions (Fig. 1d, middle panel, marked with red shadow), where the aromatic rings formed two edge-to-face π–π interactions, with dihedral angles of 56° and 47° and closest contacts of 3.69 Å and 3.76 Å, respectively (Fig. 1d, subpanel “5”).

Fig. 1. Crystallographic structure of water-enriched Ww assemblies.

(a) scanning electron microscopy image of Ww crystals. (b) Optical microscopy image of a Ww crystal labelled with the crystallographic dimensions. Magnification scale: X60. (c) Monomeric structure of the crystal, showing one dipeptide building block incorporating four water molecules by hydrogen bonding. The water molecules are numbered for clarity. Adopted from ref. 9. (d) Hydrophilic/hydrophobic partitioning and layering in the Ww crystal. The hydrophilic section composed of a water layer and the peptide backbone is shaded in blue and the hydrophobic section comprising side-chain indole rings is shaded in red. Zoom-in panel “1”: a lateral view of the peptide assembly with water molecules strung along the b axis. The hydrogen bonds are labelled in different colours to highlight their distinct roles in the system. The green set composes a large channel, the magenta group comprises a small channel, and the blue subgroup provides support by bridging the adjacent monomers. Panel “2”: top view of the two channels composed of hydrogen bonds between peptide backbones and water molecules. The large and small channels are shaded in green and magenta, respectively, consistent with the corresponding hydrogen bonds. Panel “3”–“4”: front and side view, respectively, of the water layer in the crystal. Panel “5”: magnified view of the hydrophobic region composed of side-chain indole rings. The two types of aromatic interactions are indicated in red and green, respectively, with the dihedral angle and nearest atomic distance labelled. The carbon, nitrogen and oxygen atoms are represented as grey, blue and red spheres, respectively. The hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity, and the hydrogen bonds are labelled between the donor and acceptor atoms.

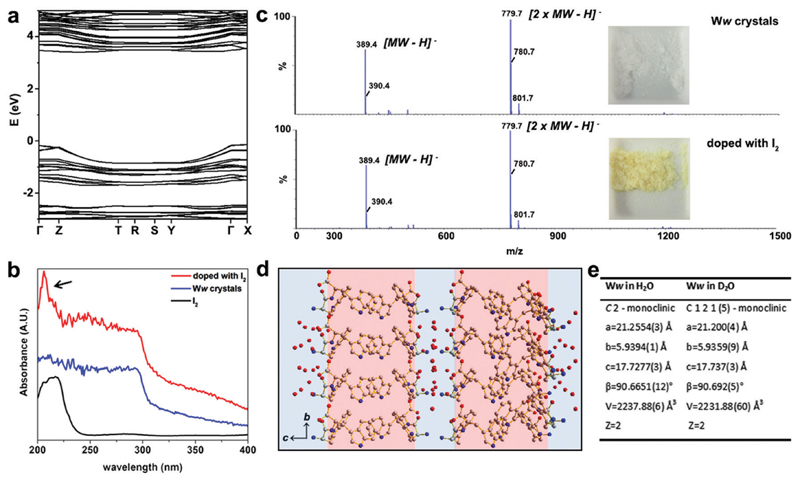

The electronic band structure of pristine Ww crystals was calculated by density functional theory (Fig. 2a). The corresponding bandgap was found to be 3.87 eV, indicating the wide-gap semiconducting nature of the supramolecular architectures.9,12 Aiming to further modulate these properties, we doped the Ww crystals. As state-of-the-art chemical or electrochemical doping approaches may alter the supramolecular conformations,11 we applied two alternative doping strategies, i.e., iodine adsorption and isotope replacement.

Fig. 2. Doping of Ww crystals through iodine adsorption and introduction of neutrons.

(a) The electronic band structure of Ww crystals calculated by density functional theory. (b) UV-vis absorbance spectra of Ww crystals before (blue) and after (red) doping with iodine. The reference absorption of iodine alone (black) is shown for comparison. (c) Mass spectrometry of Ww crystals before (upper panel) and after (lower panel) doping with iodine, showing the same molecular weights. The insets show photographs of the peptide crystals before and after iodine doping. (d) Crystallographic structure of Ww crystals prepared in deuterium oxide. (e) Crystallographic data collection table of Ww crystals in normal water and in deuterium oxide, showing nearly-identical crystal parameters.

The UV-vis absorption spectra at 200–295 nm demonstrated a step-like absorbance of the Ww crystals (Fig. 2b), characteristic of 2D quantum well structures which are likely located at the hydrogen bonding and aromatic interaction regions.13 After immersion in iodine vapor for several hours, the Ww crystals were decorated with iodine, showing the characteristic absorbance peak of iodine at 206 nm (indicated by an arrow in Fig. 2b).14 Iodine vapor oxidation is widely applied for chemical doping of organic semiconductors,11 yet the redox reactions inevitably damage the original molecular structures. In contrast, the molecular weight of the Ww crystals before and after iodine doping remained almost identical (389.4 amu; Fig. 2c) and the supramolecular morphologies were conserved (Fig. S1a, ESI†), indicating the original structure was retained. Notably, the colour changed from the original white into yellow (inset in Fig. 2c).

Motivated by the extensive contribution of water molecules to the assemblies, another doping strategy was employed by using deuterium oxide as the solvent instead of H2O. The introduction of neutrons in this way retained the molecular backbone of the Ww crystals which still conserved the D2O layers (Fig. 2d), morphology (Fig. S1b, ESI†) and lattice parameters, with only a minor change in symmetry (Fig. 2e and Cif. S2, ESI†). This analysis indicated that similar to iodine adsorption, the introduction of neutrons did not significantly alter the structure of the Ww crystals (Fig. S1b, ESI†).

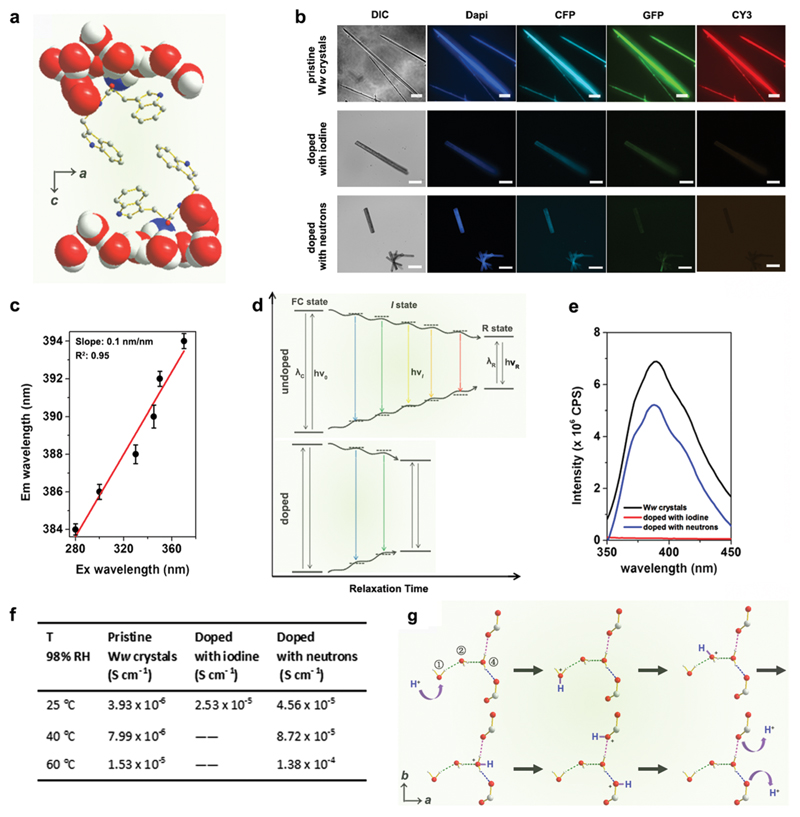

The emission maxima of the pristine Ww side-chain indole rings showed a significant red edge excitation shift (REES)15 as they were surrounded by a highly polar environment comprising extensively hydrogen-bonded water molecules and backbone terminals (Fig. 3a).16 The relaxation (reorientation) of the molecules in such polar media is slower than that required for fluorescence lifetime,17 thus endowing the Ww assemblies with diverse colours of emission ranging from blue to red under different excitations (Fig. 3b, upper row). The red-shift magnitude was found to be 10 nm (from 384 nm to 394 nm), with a linear slope of 0.1 nm nm−1 (Fig. 3c and Fig. S2, ESI†). A plausible explanation is that during the relaxation of dipoles of highly-restricted water molecules with respect to the excited indole rings, various intermediate states (I states) between the initial excited state (Franck–Condon state, FC state) and the final relaxed one (R state) were formed (Fig. 3d, upper panel) to minimize the interaction energy,15 thus resulting in the REES phenomenon.17 However, the REES effect was attenuated upon doping, with iodine doping showing more significantly weakened fluorescence (Fig. 3b, lower rows). Doping created defect charge states that allowed the otherwise restricted water molecules to move around the indole rings with a higher degree of freedom. This can reduce the relaxation time and weaken the REES effect (Fig. 3d, lower panel), probably by promoting charge hopping that helped shrink the electron transitions and emission intensities (see fluorescence data in Fig. 3e).18

Fig. 3. Doping-enhanced charge transfer of Ww crystals.

(a) Crystallographic structure showing the side-chain indole rings of Ww surrounded by a hydrogen-bonded, motion-restricted medium composed of water molecules and polar atoms (oxygen, nitrogen) of peptide backbones. (b) Fluorescent microscopy images of pristine Ww crystals (upper row; scale bar = 30 μm), doped with iodine (middle row; scale bar: 50 μm) and with neutrons (lower row; scale bar = 200 μm), showing the attenuated fluorescence upon doping. DIC: differential interference contrast mode; dapi: 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole filter (Ex: 340–380 nm, Em: 435–485 nm); CFP: cyan fluorescent protein filter (Ex: 420–445 nm, Em: 460–510 nm); GFP: green fluorescent protein filter (Ex: 455–485 nm, Em: 500–545 nm); CY3: cyanine 3 filter (Ex: 528–553 nm, Em: 590–650 nm). (c) Maximal emission of pristine Ww crystals vs. the excitation wavelength, showing a characteristic linear relationship. (d) Schematic representation showing the continuous medium relaxation surrounding the indole rings in pristine (upper panel) and doped (lower panel) Ww crystals. The “I state” refers to one of the intermediate states between the initial excited state (FC state) and the final solvent relaxed state (R state). v0, vi and vR represent the frequencies corresponding to the FC, I and R states, respectively, while λC and λR denote the maximal emission wavelengths associated with these states. (e) Maximal emission spectra of pristine (black), iodine-(red) and neutron-(blue) doped Ww crystals upon excitation at 330 nm. (f) Table summarizing the proton conductivity of pristine and doped Ww crystals at different temperatures and 98% RH. (g) Schematic illustration of proton translocation along the hydrogen-bonded water molecule chain inside the Ww crystals, following the Grotthuss mechanism. The moving hydrogen nucleus is labelled in blue.

The increased degree of freedom of the hydrogen-bonded water molecules also implies an enhanced proton transfer upon doping (Fig. S3, ESI†). Pristine Ww showed a Grotthuss-type proton conduction mechanism19 of 3.93 × 10−6 S cm−1 at room temperature (25 °C, RT) under relative humidity (RH) of 98% (Fig. 3f) and 1.53 × 10−5 S cm−1 at an elevated temperature (60 °C) with calculated activation energy of 0.33 ± 0.02 eV (Fig. S4, ESI†). Proton conductivity under ambient conditions (RT and 98% RH) increased by an order of magnitude in iodine-doped (2.53 × 10−5 S cm−1) and neutron-doped (4.56 × 10−5 S cm−1) crystals (Fig. 3f). The conductivity of the neutron-doped crystal further increased by an order of magnitude at 60 °C (1.38 × 10−4 S cm−1), with a smaller activation energy of 0.27 ± 0.04 eV (Fig. S4, ESI†). The activation energy for iodine-doped Ww assemblies was not measured due to the collapse of the tested sample upon rapid sublimation of the adsorbed iodine at the elevated temperature. Fig. 3g depicts the proton translocations inside the Ww crystals following the Grotthuss model. A mobile proton (marked in blue, Fig. 3g) hops along the ①–②–④ water molecules to the backbone carboxylic group, and is then released out. As the motions of the water molecules are restricted in pristine Ww crystals, proton hopping is limited. Iodine doping generates a strong electrostatic attraction between the valence electrons of the iodine atoms and the protons of the water molecules. When the water molecules are replaced with deuterium oxide, the neutrons slightly increase the molecular mass as well as the momentum of the deuterium nuclei. Therefore, both doping methods could abate the restriction, leading to a decrease of the activation energy and enhancement of the proton conductivity.

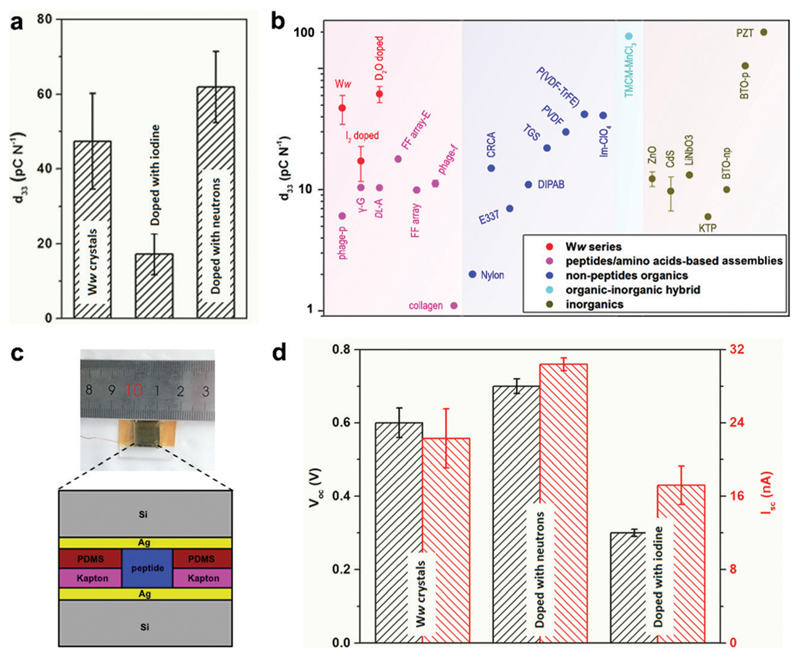

The extensive and directional hydrogen bonding along with the aromatic interactions endow the Ww assemblies with high mechanical rigidity and stability,7,20 showing a statistical Young’s modulus of 14.6 ± 2.0 GPa and a point stiffness of 75.1 ± 10.1 N m−1 (Fig. S5, ESI†), thus exemplifying their promising potential for pressure responsive applications.21 Piezoelectric force microscopy (PFM) characterization revealed the vertical coefficient of the pristine Ww crystals, denoted here as the d33 coefficient, to be 47.4 ± 12.8 pC N−1 (Fig. 4a and Fig. S6a, S7a, ESI†), 3–8 fold higher than previously reported peptide-based supramolecular structures22–25 such as diphenylalanine assembling arrays (9.9–17.9 pC N−1)26,27 (Fig. 4b, magenta region). Furthermore, the average piezo-response was significantly higher than most of the reported non-peptide organic materials such as electrically-poled poly(vinylidene fluoride/trifluoroerhylene) (P(VDF–TrFE), 42 pC N−1) (Fig. 4b, blue region),28 and inorganic piezoelectric materials such as poled LiNbO3 (13.2–22 pC N−1) (Fig. 4b, grey region).23 However, after doping with iodine, the d33 value decreased to 17.2 ± 5.5 pC N−1 (Fig. 4a and Fig. S6b, S7b, ESI†), probably due to the force dispersion of the adsorbed iodine layer during the pressure engagement. In contrast, the average d33 value was enhanced to 61.9 ± 9.5 pC N−1 after doping with neutrons (Fig. 4a and Fig. S6c, S7c, ESI†), a significantly high value for (bio)-organic constituents (Fig. 4b), which represents very large voltage constant (2.3 V m N−1) and normalized energy density for a given force and aspect ratio (67 J) compared to state-of-the-art piezoelectric ceramics (~0.05 V m N−1 and ~14 J).

Fig. 4. Doping-mediated piezoelectricity enhancement of Ww crystals.

(a) Comparison of the d33 coefficients of pristine and doped Ww crystals measured using PFM. (b) Comparison of d33 coefficients among different classes of organic and inorganic materials. The magenta, blue, cyan and grey regions show the range of d33 values for peptide/amino acid self-assemblies, non-peptide organic materials, organic–inorganic hybrids and inorganic constituents, respectively. The Ww series (pristine and doped with iodine or neutrons) are denoted in red for comparison. From left to right: M13 bacteriophage nanopillars (phage-p),22 γ-glycine (γ-G),24 dl-alanine (dl-A),25 FF microrod arrays prepared using electric field (FF array-E),26 FF microrod arrays (FF array),27 M13 bacteriophage thin films (phage-f) and type I collagen films (collagen);23 nylon, Rochelle salt (E337) and triglycine sulfate (TGS),31 diisopropylammonium bromide (DIPAB),32 croconic acid (CRCA),33 poly(vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF),34 poly(vinylidene fluoride/trifluoroerhylene) (P(VDF-TrFE)),28 imidazolium perchlorate (Im-ClO3);35 trimethylchloromethyl ammonium trichloromanganese(ii) (TMCM-MnCl3);31 ZnO and CdS,36 periodically poled lithium niobate (LiNbO3),23 potassium titanyl phosphate (KTP), non-poled and poled BaTiO3 [001],31 lead zirconate titanate (PZT).37 (c) Schematic cross-section diagram of the proof-of-concept generator used as a direct power source comprising the peptide crystals as the active components. The inset shows a photographic picture of the device. (d) Comparison of the output signals (Voc, Isc) from the generators utilized as a direct power source using undoped or doped Ww crystals as the active components, as designed in (c).

Prototype piezoelectric power generators were further fabricated using the Ww crystals as the active components (Fig. 4c and Fig. S8, ESI†). An axial force of 38 N (stress of 26.4 × 104 Pa) produced an open-circuit voltage (Voc) of 0.6 ± 0.04 V and a short-circuit current (Isc) of 22.3 ± 3.2 nA for a pristine Ww assembly-based device (Fig. 4d and Fig. S9a, ESI†), with an equivalent resistance of 26.9 MΩ. Neutron-doped assemblies showed enhancement of 17% for Voc (0.7 ± 0.02 V) and 36% for Isc (30.4 ± 0.7 nA) compared to the pristine Ww-based device (Fig. 4d and Fig. S9b, ESI†), consistent with the increase of longitudinal piezo-response. However, the equivalent resistance was almost identical, confirming the ability of neutron doping to enhance the electron transfer of the peptide assemblies. In comparison, the iodine-doped crystals performed relatively poorly, with the peak Voc and Isc reaching 0.3 ± 0.01 V and 17.2 ± 2.1 nA, respectively (Fig. 4d and Fig. S9c, ESI†). The lower output signals were consistent with the relatively low d33 piezo-response. Nevertheless, the extent of decrease was less than the piezoelectric coefficient, with the equivalent resistance calculated to be 17.4 MΩ, 35% smaller than that of the pristine Ww-based device, thus demonstrating the electron transfer enhancement upon iodine doping. In general, both undoped and doped Ww crystals showed high conductivity and piezoelectric currents, which is consistent with their wide-gap semi-conducting nature, suggesting potential utility in bio-integrated micro-devices for biomedical29 and bio-electronic applications.30

In summary, we present an aromatic dipeptide composed of l-W and d-W, which crystallized into a layered organic-water structure. The extensive and directional hydrogen bonding resulted in significant electronic transitions and supramolecular dipoles, thus leading to wide-range fluorescent emissions and large piezoelectric coefficients of the bioinspired architectures. We further introduced two doping approaches, iodine adsorption rather than the commonly-applied redox, and introduction of neutrons through exchanging H2O with D2O. Both doping strategies prompted the motion of the hydrogen-bonded water molecules, thus attenuating the REES effect and facilitating charge hopping. The resulting enhancement of the charge transfer significantly improved the performances of piezoelectric power generators fabricated using bioinspired assemblies. In addition, the neutron-doping strategy developed herein provides a first example for the possibility of using isotope replacement, such as 14N to 15N or 16O to 18O etc., to modulate the properties of bioorganic assemblies.

Supplementary Material

† Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available: Full Experimental section and additional data are provided. CCDC 1853728 and 1939621. For ESI and crystallographic data in CIF or other electronic format see DOI: 10.1039/c9ee02875g

Broader context.

Peptide assemblies show promising potential for energy applications in biological environments and at bio-machine interfaces. Nevertheless, peptide molecules have inherent energy transfer limitations. The introduction of extensive water molecules can relieve these shortcomings. This study reports a simple aromatic dipeptide, l-tryptophan-d-tryptophan, which crystallizes into sandwich-like structures composed of alternating layers of water and peptide molecules. The extensive and directional hydrogen bonding in the water layers results in significant red-edge excitation shift and large supramolecular dipoles in the peptide assemblies. We further develop two doping technologies, iodine adsorption and isotope replacement by exchanging H2O with D2O. Both iodine and neutron doping result in enhancement of the energy transfer and significantly improve the performance of piezoelectric microdevices. This simple water-layered peptide system and the unique doping strategies offer a promising solution for the energy transfer obstacle hindering the application of bioinspired supramolecular architectures. Especially, we demonstrate that isotope replacement can be used as a doping tool, potentially revolutionizing the commonly-used methodologies that, until now, could only focus on charged groups. This is a fundamental step towards the design and modulation of bioinspired assemblies, paving the way for the realization of a new generation of bio-integrated microdevices for energy generation and storage.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the European Research Council under the European Union Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (no. 694426) (E. G.), Huawei Technologies Co., Ltd (E. G.), Joint NSFC-ISF Grant (no. 3145/19) (E. G.), Science Foundation Ireland (SFI, no. 15/CDA/3491 and SSPC 12/RC/2275) (D. T.), Irish Research Council Embark Postgraduate Scholarship (no. GOIPG/2018/1161) (J.O’D.). SFI Opportunistic Fund (no. 12/RI/2345/SOF) is acknowledged for NTEGRA Hybrid Nanoscope used in Piezoforce Microscopy. The authors thank Zohar A. Arnon for fluorescence characterization, Dr Kangcai Wang for proton conductivity characterization, Dr Jie Jiang for density functional theory calculations of band structures, and Dr Sigal Rencus-Lazar for language editing assistance, as well as the members of the Tofail and Gazit laboratories for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Kai Tao: 0000-0003-3899-5181

Joseph O’ Donnell: 0000-0002-7474-4788

Sarah Guerin: 0000-0002-2442-4022

Linda J. W. Shimon: 0000-0002-7861-9247

Yi Cao: 0000-0001-7922-7766

Damien Thompson: 0000-0003-2340-5441

Ehud Gazit: 0000-0001-5764-1720

Author contributions

S. A. M. T and E. G. conceived and designed the work; K. T. conducted the crystal growth, microscopy, SEM, UV-vis absorbance, MS and fluorescence characterizations; J. O’D., E. U. H., C. S., S. G., D. T. and S. A. M. T. investigated the piezoelectric coefficients; H. Y. and R. Y. fabricated the power generator and characterized its performance; K. T. and L. J. W. S. performed crystallography analysis; B. X. and Y. C. conducted experimental measurements of mechanical properties; K. T. coordinated all the work, analysed the results, wrote and edited the manuscript with input from all authors.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Notes and references

- 1.Yan XH, Zhu P, Li JB. Chem Soc Rev. 2010;39:1877. doi: 10.1039/b915765b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lampel A, et al. Science. 2017;356:1064. doi: 10.1126/science.aal5005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adamcik J, et al. Nat Nanotechnol. 2010;5:423. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2010.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aida T, Meijer E, Stupp SI. Science. 2012;335:813. doi: 10.1126/science.1205962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tao K, Makam P, Aizen R, Gazit E. Science. 2017;358:eaam9756. doi: 10.1126/science.aam9756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang SG. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:1171. doi: 10.1038/nbt874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knowles TP, Buehler MJ. Nat Nanotechnol. 2011;6:469. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2011.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amit M, et al. Adv Funct Mater. 2014;24:5873. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tao K, et al. Mater Today. 2019;30:10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.mattod.2019.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Erwin SC, et al. Nature. 2005;436:91. doi: 10.1038/nature03832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Enengl C, et al. Adv Funct Mater. 2015;25:6679. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tao K, et al. Nat Commun. 2018;9:3217. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05568-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amdursky N, Gazit E, Rosenman G. Adv Mater. 2010;22:2311. doi: 10.1002/adma.200904034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wei Y, Liu C, Mo L. Guangpuxue Yu Guangpu Fenxi. 2005;25:86. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lakowicz JR, Keating-Nakamoto S. Biochemistry. 1984;23:3013. doi: 10.1021/bi00308a026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chattopadhyay A, Haldar S. Acc Chem Res. 2013;47:12. doi: 10.1021/ar400006z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berger O, et al. Nat Nanotechnol. 2015;10:353. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2015.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Especially, the absorption to the excitation light of the iodine layer further decreased the emission intensities.

- 19.Ordinario DD, et al. Nat Chem. 2014;6:596. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knowles TP, et al. Science. 2007;318:1900. doi: 10.1126/science.1150057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liao W-Q, et al. Science. 2019;363:1206. doi: 10.1126/science.aav3057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shin D-M, et al. Energy Environ Sci. 2015;8:3198. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee BY, et al. Nat Nanotechnol. 2012;7:351. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2012.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guerin S, et al. Nat Mater. 2018;17:180. doi: 10.1038/nmat5045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guerin S, et al. Phys Rev Lett. 2019;122 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.122.047701. 047701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nguyen V, Zhu R, Jenkins K, Yang RS. Nat Commun. 2016;7 doi: 10.1038/ncomms13566. 13566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nguyen V, Jenkins K, Yang R. Nano Energy. 2015;17:323. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang H, Zhang Q, Cross L, Sykes A. J Appl Phys. 1993;74:3394. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park S, et al. Nature. 2018;561:516. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0536-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tian B, et al. Phys Biol. 2018;15 doi: 10.1088/1478-3975/aa9f34. 031002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.You Y-M, et al. Science. 2017;357:306. doi: 10.1126/science.aai8535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fu D-W, et al. Science. 2013;339:425. doi: 10.1126/science.1229675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Horiuchi S, Tsutsumi Jy, Kobayashi K, Kumai R, Ishibashi S. J Mater Chem C. 2018;6:4714. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kepler R, Anderson R. J Appl Phys. 1978;49:4490. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang Y, et al. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53:5064. doi: 10.1002/anie.201400348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kobiakov I. Solid State Commun. 1980;35:305. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Savakus H, Klicker K, Newnham R. Mater Res Bull. 1981;16:677. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.