Abstract

Cryptosporidium spp. and Enterocytozoon bieneusi are two well-known protist pathogens which can result in diarrhea in humans and animals. To examine the occurrence and genetic characteristics of Cryptosporidium spp. and E. bieneusi in pet red squirrels (Sciurus vulgaris), 314 fecal specimens were collected from red squirrels from four pet shops and owners in Sichuan province, China. Cryptosporidium spp. and E. bieneusi were examined by nested PCR targeting the partial small subunit rRNA (SSU rRNA) gene and the ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) gene respectively. The infection rates were 8.6% (27/314) for Cryptosporidium spp. and 19.4% (61/314) for E. bieneusi. Five Cryptosporidium species/genotypes were identified by DNA sequence analysis: Cryptosporidium rat genotype II (n = 8), Cryptosporidium ferret genotype (n = 8), Cryptosporidium chipmunk genotype III (n = 5), Cryptosporidium rat genotype I (n = 4), and Cryptosporidium parvum (n = 2). Additionally, a total of five E. bieneusi genotypes were revealed, including three known genotypes (D, SCC-2, and SCC-3) and two novel genotypes (RS01 and RS02). Phylogenetic analysis revealed that genotype D fell into group 1, whereas the remaining genotypes clustered into group 10. To our knowledge, this is the first study to report Cryptosporidium spp. and E. bieneusi in pet red squirrels in China. Moreover, C. parvum and genotype D of E. bieneusi, previously identified in humans, were also found in red squirrels, suggesting that red squirrels may give rise to cryptosporidiosis and microsporidiosis in humans through zoonotic transmissions. These results provide preliminary reference data for monitoring Cryptosporidium spp. and E. bieneusi infections in pet red squirrels and humans.

Subject terms: Parasite biology, Parasite development

Introduction

Cryptosporidium spp. and Enterocytozoon bieneusi, causative agents of cryptosporidiosis and microsporidiosis, are two important opportunistic intestinal pathogens that can infect vertebrate and invertebrate, posing a significant threat to public health1. Humans are infected with these pathogens mainly via the fecal-oral route with anthroponotic and zoonotic transmission or via food-borne and water-borne transmission2,3. Clinical manifestations of infection with these pathogens are often inconsistent due to the variabilities in the health condition of infected hosts4,5. In healthy individuals, these pathogens usually cause asymptomatic infection or self-limiting diarrhea6. However, infection may also result in chronic or life-threatening diarrhea in immunocompromised individuals, such as patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and patients who had undergone organ transplantation7. In addition to humans, there are a variety of animals that can act as hosts for these two pathogens, including various mammals, reptiles, birds, amphibians and insects8. Therefore, Cryptosporidium spp. and E. bieneusi have been recognized as category B pathogens by the National Institutes of Health due to their ease of transmission in spite of low mortality9.

To detect and evaluate potential zoonotic transmissions, it is necessary to accurately distinguish Cryptosporidium spp. and E. bieneusi on the molecular level10. To date, at least 37 species and over 70 genotypes of Cryptosporidium spp. have been described11. Among them, 11 Cryptosporidium species have been identified in rodents, Cryptosporidium parvum and C. muris are the most common12. For E. bieneusi, more than 474 genotypes have been identified based on the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region of the rRNA gene13, and more than 35 genotypes have been determined in rodents14. These genotypes can be classified into eleven groups (groups 1–11) by phylogenetic analyses13. Group 1 comprises the majority of zoonotic potential genotypes, whereas the remaining (groups 2–11) are considered as the host-adapted groups, which are mostly found in specific hosts or water13.

In China, Cryptosporidium spp. and E. bieneusi have been detected in a wide range of hosts, including carnivores, lagomorphs, primates, birds, and rodents14,15. Pet rodents, in particular (e.g. chinchillas, red-bellied tree squirrels, guinea pigs, and chipmunks), are considered potential sources of Cryptosporidium spp. and E. bieneusi infections in humans16–19. The red squirrel (Sciurus vulgaris) is a popular pet in China, which is widely bred in pet shops and homes for its appearance and mild-mannered nature. However, there is no published data regarding the prevalence of Cryptosporidium spp. and E. bieneusi in pet red squirrels, and the role of the red squirrels in the transmission of the two pathogens remains poorly investigated. Thus, we examined the occurrence of Cryptosporidium spp. and E. bieneusi in red squirrels, and evaluated their potential role in the zoonotic transmission of human cryptosporidiosis and microsporidiosis.

Results

Occurrence of Cryptosporidium spp. and E. bieneusi

The overall prevalence of Cryptosporidium spp. in pet red squirrels was 8.6% (27/314, 95% CI: 5.5–11.7%). All pet shops were positive for Cryptosporidium, and the prevalence ranged from 2.2% to 16.2%; significant differences were observed (χ2 = 0.028, df = 4, P < 0.05; Table 1). The prevalence of Cryptosporidium spp. among males and females were 8.1% and 9%, respectively, but the difference was not statistically significant (χ2 = 0.086, df = 1, P > 0.05). The differences in prevalence of Cryptosporidium spp. among squirrels of different ages were not statistically significant (χ2 = 0.093, df = 1, P > 0.05) (Table 2). Moreover, a significant correlation between the different sources and Cryptosporidium spp. infection (P = 0.01) was observed by logistic regression analysis.

Table 1.

Occurrence of Cryptosporidium spp. and Enterocytozoon bieneusi in pet red squirrels from different sources in Southwestern China.

| Sources | No. of examined | Cryptosporidium spp. | E. bieneusi | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of positive | Prevalence (%) (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | Species/Genotype (n) | No. of positive | Prevalence (%) (95% CI) |

OR (95% CI) | Genotype (n) | ||

| Pet shop 1 | 58 | 2 |

3.4% (0.014–0.083) |

reference | rat genotype I (2) | 5 |

8.6% (0.012–0.161) |

reference | D (3), RS01 (2) |

| Pet shop 2 | 74 | 12 |

16.2% (0.076–0.248) |

5.4 (1.2–25.3) | rat genotype II (8), chipmunk genotype III (3), C. parvum (1) | 16 |

21.6% (0.12–0.312) |

2.9 (1.0–8.5) | D (6), SCC-2 (8), SCC-3 (2) |

| Pet shop 3 | 76 | 8 |

10.5% (0.035–0.176) |

3.2 (0.7–16.1) | ferret genotype (6), chipmunk genotype III (2) | 21 |

27.6% (0.173–0.379) |

4.0 (1.4–11.5) | D (13), SCC-2 (6), RS02 (2) |

| Pet shop 4 | 61 | 4 |

6.6% (0.002–0.129) |

2.0 (0.3–11.2) | rat genotype I (2), ferret genotype (2) | 14 |

23% (0.121–0.338) |

3.2 (1.1–9.4) | D (4), SCC-3 (10) |

| owners | 45 | 1 |

2.2% (0.023–0.067) |

0.6 (0.1–7.2) | C. parvum (1) | 5 |

11.1% (0.016–0.207) |

1.3 (0.4–4.9) | D (1), SCC-2 (4) |

| Total | 314 | 27 |

8.6% (0.055–0.117) |

rat genotype II (8), ferret genotype (8), chipmunk genotype III (5), rat genotype I (4), C. parvum (2) | 61 |

19.4% (0.150–0.238) |

D (27), SCC-2 (18), SCC-3 (12), RS01 (2), RS02 (2) | ||

Table 2.

Occurrence of Cryptosporidium spp. and Enterocytozoon bieneusi in pet red squirrels according to sex and age.

| Factor | Characteristics | No. of examined | Cryptosporidium spp. | E. bieneusi | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of positive | Prevalence (%) (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | No. of positive | Prevalence (%) (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |||

| Sex | Male | 148 | 12 | 8.1% (0.037–0.126) | reference | 27 | 18.2% (0.119–0.245) | reference |

| Female | 166 | 15 | 9% (0.046–0.134) | 1.1 (0.5–2.5) | 34 | 20.5% (0.143–0.267) | 1.2 (0.7–2.0) | |

| Age | ≤3 months | 154 | 14 | 9.1% (0.045–0.137) | reference | 32 | 20.8% (0.143–0.273) | reference |

| >3 months | 160 | 13 | 8.1% (0.038–0.124) | 0.9 (0.4–1.9) | 29 | 18.1% (0.121–0.242) | 0.8 (0.5–1.5) | |

The overall prevalence of E. bieneusi in pet red squirrels was 19.4% (61/314, 95% CI: 15–23.8%). E. bieneusi was found in all four pet shops investigated, with infection rates ranging between 8.6% and 27.6%. The difference was statistically significant (χ2 = 0.036, df = 4, P < 0.05; Table 1). The prevalence of E. bieneusi in female red squirrels (20.5%) was higher than male (18.2%), but the difference was not statistically significant (χ2 = 0.251, df = 1, P > 0.05). The differences in prevalence of E. bieneusi among squirrels of different ages were not statistically significant (χ2 = 0.353, df = 1, P > 0.05) (Table 2). No mixed infections of the two pathogens were found in red squirrels in our study. Similarly, a significant correlation between the different sources and E. bieneusi infection (P = 0.01) was observed by logistic regression analysis.

Cryptosporidium species/genotypes

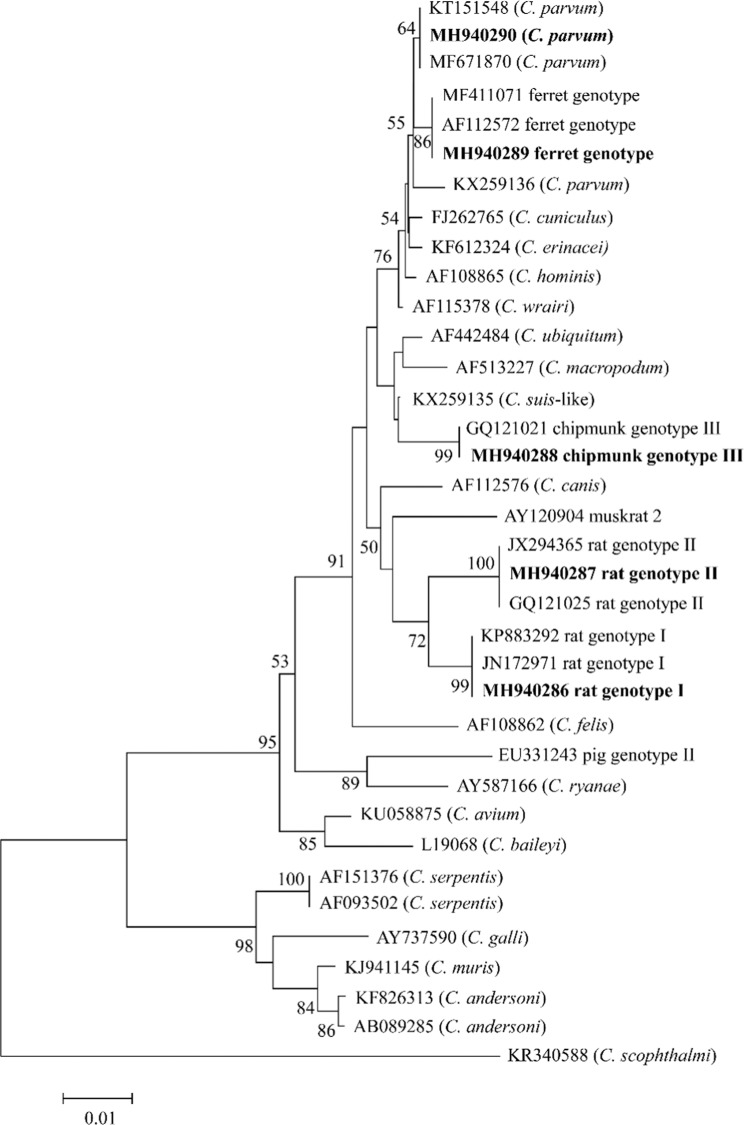

Twenty-seven Cryptosporidium-positive samples were genotyped by sequence analysis of the SSU rRNA gene, and five Cryptosporidium species/genotypes were identified: Cryptosporidium rat genotype II (8/27, 30%), Cryptosporidium ferret genotype (8/27, 30%), Cryptosporidium chipmunk genotype III (5/27, 18.5%), Cryptosporidium rat genotype I (4/27, 14.8%), and C. parvum (2/27, 7.4%). Phylogenetic relationship analysis confirmed the identity of Cryptosporidium species/genotypes (Fig. 1). Cryptosporidium rat genotype II and Cryptosporidium ferret genotype were the two most predominant genotypes (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic relationships between the partial Cryptosporidium SSU rRNA gene from red squirrels and the Cryptosporidium spp. or genotypes deposited in GenBank. The GenBank accession number of each Cryptosporidium species or genotype is shown in parentheses. Bootstrap values above 50% from 1,000 replicates are shown at the nodes. The newly generated sequences are indicated in bold.

At the SSU rRNA locus, eight Cryptosporidium rat genotype II isolates had 100% homology between each other and were identical to that (GQ121025) from Rattus tanezumi in China and those from R. rattus in Australia (JX294365). The eight Cryptosporidium ferret genotype sequences were identical to reference sequences MF411071 (from Sciurus vulgaris in Italy) and AF112572 (from ferrets in the USA). Cryptosporidium chipmunk genotype III was identical to the reference sequence GQ121021 (from Siberian chipmunks in China); Cryptosporidium rat genotype I was identical to the reference sequences KP883292 (from R. rattus in Iran) and JN172971 (from R. norvegicus in Sweden); and C. parvum was identical to reference sequences MF671870 (from dairy cattle in China) and KT151548 (from coturnix in Iraq).

E. bieneusi genotypes

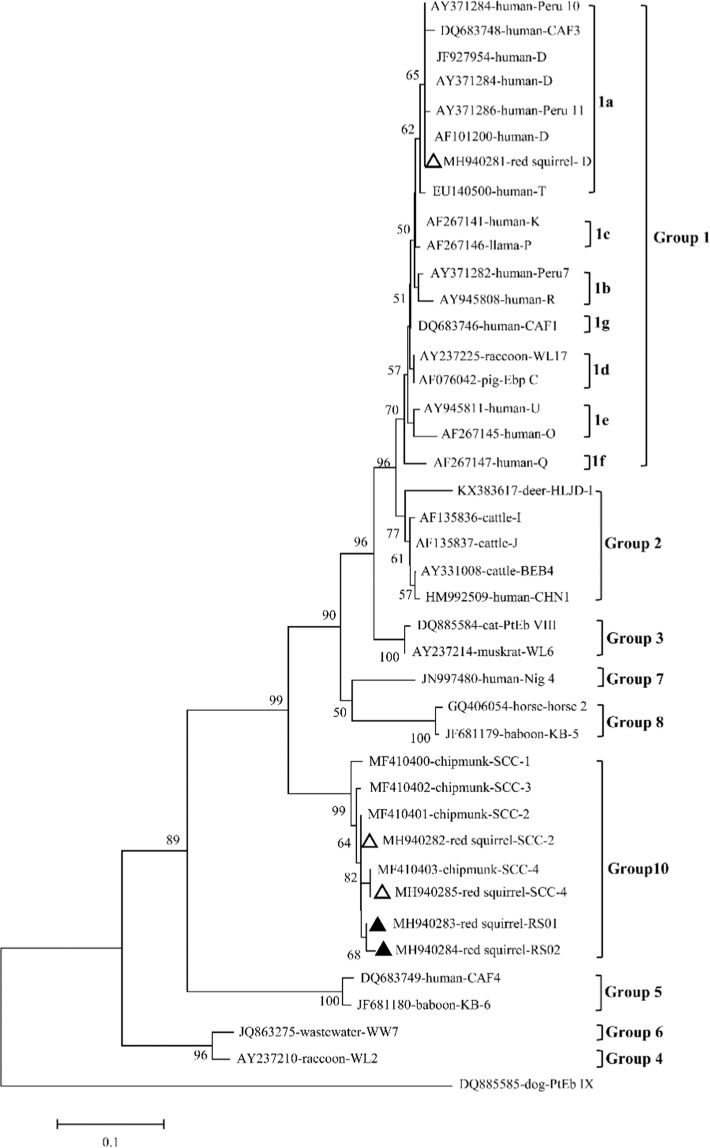

DNA sequencing and subsequent analysis of the ITS-PCR products from the 61 E. bieneusi-positive specimens revealed the existence of three known E. bieneusi genotypes (D, SCC-2, SCC-4) and two novel genotypes, which were named RS01 and RS02. Genotype D was the most prevalent (44.3%, 27/61) and showed 100% homology with the sequences JF927954 (from humans in China) and AY371284 (from humans in Peru). Genotypes SCC-2 and SCC-4 had 100% homology with the two sequences MF410401 and MF410403, respectively.

With regard to the two novel genotypes, RS01 displayed two single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within the 243 bp of the ITS gene sequence of E. bieneusi (G/A at positions 178 and 324), when compared with the genotype SCC-2 (MF410401), which showed 99% homology. RS02 had three SNPs (G/A at positions 101 and 178, A/T at position 108) in comparison with genotype SCC-2, with 99% homology.

Phylogenetic relationship of E. bieneusi

A phylogenetic analysis of the ITS gene sequences of all the genotypes of E. bieneusi obtained here and reference genotypes published previously revealed that genotype D clustered in group 1 and further clustered into 1a, whereas genotypes SCC-2, SCC-4, and two novel genotypes (RS01 and RS02) clustered in group 10 (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic relationships of the E. bieneusi genotypes identified in this study and other reported genotypes. The phylogeny was inferred with a neighbor-joining analysis of the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequences based on distances calculated with the Kimura two-parameter model. Bootstrap values greater than 50% from 1,000 replicates are shown at the nodes. Genotypes with open circles and solid circles are known and novel genotypes identified in this study, respectively.

Discussion

In 314 fecal samples of red squirrel, we first demonstrated the presence of Cryptosporidium spp. and E. bieneusi. The occurrence of Cryptosporidium spp. (8.6%, 27/314) was lower than the average prevalence previously reported in rodents (15.2%, 290/1911) (Table 3), but higher than those reported in laboratory rats in Nigeria (1.5%)20, brown rats in Iran (6.6%)21, and brown rats (6.2%), laboratory mice (1.7%), laboratory rats (4%), hamsters (7.8%), squirrel monkeys (4.2%), and Bamboo rats (3.3%) in China22–24. Cryptosporidium spp. has been reported in multiple rodent species, with an infection rate of 1.5% in laboratory rats to 85.0% in guinea pigs16,25–27. The relatively low occurrence of Cryptosporidium spp. in this study may be explained by the fact that the pet squirrels lived in clean environments and were kept in separate cages. The prevalence of E. bieneusi was 19.4%, which was similar to that in two recent studies in Sichuan province for E. bieneusi infection rates in red-bellied tree squirrels (16.7%, 24/144)18 and chipmunks (17.6%, 49/279)17. The prevalence of E. bieneusi in rodents ranged from 1.1% to 100% (Table 4)12,19,28–30. As proposed in other studies, factors contributing to the prevalence of these pathogens may include the examination method, age, sex, season, host health status, feeding density, sample size, geo-ecological conditions, and living conditions31–33.

Table 3.

Occurrence of Cryptosporidium species/genotypes in rodents from different countries.

| Country | Host (common name) |

Scientific name | No. of samples | No. of positive (%) | Species/Genotype (n) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japan | Brown rats | Rattus norvegicus | 50 | 19 (38) | C. meleagridis (1), C. parvum (1), New genotypes (11) | Kimura et al., 2007 |

| USA | Opossum | Didelphis virginiana | — | 2 | Marsupial genotype (2) | Feng et al., 2007 |

| Chipmunk | Tamias striatus | — | 1 | C. baylei (1) | ||

| Gray squirrel | Sciurus carolinensis | — | 1 | Skunk genotype (1) | ||

| White-footed mouse | Peromyscus leucopus | — | 3 | C. parvum (3) | ||

| Deer mouse | Peromyscus maniculatus | — | 3 | C. parvum (2), Muskrat II genotype (1) | ||

| Red-backed vole | Clethrionomys gapperi | — | 2 | C. parvum (1), Muskrat II genotype (1) | ||

| Meadow vole | Microtus pennsylvanicus | — | 5 | Muskrat II genotype (5) | ||

| House mouse | Mus musculus | — | 1 | C. parvum (1) | ||

| Australia | Black rats | Rattus rattus | 85 | 7 (8.2) | rat genotype III (4), rat genotype II (3) | Koehler et al., 2018 |

| Swamp rats | Rattus lutreolus | 21 | 3 (14.3) | C. viatorum (3) | ||

| Philippines | Asian house rat | Rattus tanezumi | 83 | 37 (44.6) | rat genotype III (18), rat genotype IV (5), suis-like genotype (5), C. scrofarum (3), rat genotype I (1), rat genotype II (1), C. muris (1) | Nghublin et al., 2013 |

| Brown rat | Rattus norvegicus | 70 | 12 (18.6) | rat genotype II (5), rat genotype IV (1), C. muris (2), rat genotype I (2), C. scrofarum (1), rat genotype III (1) | ||

| Iran | Brown rat | Rattus norvegicus | 91 | 6 (6.6) | C. parvum + C. muris (6) | Gholipoury et al., 2016 |

| Nigeria | Laboratory rats | Rattus norvegicus | 134 | 2 (1.5) | C. andersoni (1), rat genotype II (1) | Ayinmode et al., 2017 |

| Slovak Republic | Striped field mouse | Apodemus agrarius | 103 | 34 (33) | C. scrofarum (18), C. parvum (9), Muskrat genotype II (3), C. environment isolate (3), C. hominis (1) | Danišová et al., 2017 |

| Bank vole | Myodes glareolus | 72 | 16 (22.2) | C. scrofarum (4), C. parvum (3), Muskrat genotype I (3), C. environment isolate (6) | ||

| Yellow-necked mouse | Apodemus flavicollis | 73 | 15 (20.5) | C. scrofarum (5), C. suis (4), C. parvum (3), C. environment isolate (3) | ||

| Italy | Red squirrels | Sciurus vulgaris | 70 | 17 (24.3) | ferret genotype (15), chipmunk genotype I (2) | Kvác et al., 2008 |

| China | Brown rat | Rattus norvegicus | 64 | 4 (6.2) | C. tyzzeri (3), rat genotype III (1) | Lv et al., 2009 |

| Asian house rat | Rattus tanezumi | 33 | 5 (15.2) | C. tyzzeri (1), rat genotype II (2), rat genotype III (2) | ||

| Laboratory mouse | Mus musculus | 229 | 4 (1.7) | C. tyzzeri (4) | ||

| Laboratory rat | Rattus norvegicus | 25 | 1 (4) | C. tyzzeri (1) | ||

| Golden hamster | Mesocricetus auratus | 50 | 16 (32) | C. muris (7), C. andersoni (5), C. parvum (4) | ||

| Siberian hamster | Phodopus sungorus | 51 | 4 (7.8) | C. parvum (2), C. muris (1), hamster genotype (1) | ||

| Campbell hamster | Phodopus campbelli | 30 | 3 (10) | C. parvum (2), C. andersoni (1) | ||

| Red squirrel | Sciurus vulgaris | 19 | 5 (26.3) | ferret genotype (5) | ||

| Siberian chipmunk | Tamias sibiricus | 20 | 6 (30) | ferret genotype (4), C. parvum (1), C. muris (1), chipmunk genotype III (1) | ||

| Guinea pig | Cavia porcellus | 40 | 34 (85) | C. wrairi (30) | ||

| Chinchillas | Chinchilla lanigera | 140 | 14 (10) | C. ubiquitum (13), C. parvum (1). | Qi et al., 2015 | |

| Brown rats | Rattus norvegicus | 242 | 22 (9.1) | rat genotype I (14), rat genotype IV (6), C. suis-like genotype (1), C. ubiquitum (1) | Zhao et al., 2018 | |

| Squirrel monkey | Saimiri sciureus | 24 | 1 (4.2) | C. hominis monkey genotype II (1) | Liu et al., 2015a | |

| Bamboo rats | Rhizomys sinensis | 92 | 3 (3.3) | C. parvum (3) | Liu et al., 2015b |

-represents unknown.

Table 4.

Occurrence and genotypes of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in rodents from different countries.

| Country | Host (common name) | Scientific name | No. of samples | No. of positive (%) | Genotypes (no.) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Czech Republic and Germany | East-European house mice | Mus musculus musculus | 127 | 14 (11) | D (6), PigEBITS5 (4), EpbA (2), C (1), H (1) | Sak et al., 2011 |

| West-European house mice | Mus musculus domesticus | 162 | 17 (10.5) | D (4), Peru 8 (4), CZ3 (4), PigEBITS5 (3), S6 (1), C (1) | ||

| United States | Eastern gray squirrel | Sciurus carolinensis | 34 | 11 (32.4) | WL4 (5), Type IV (3), WW6 (2), PtEbV + WL21 (1) | Guo et al., 2014 |

| Eastern chipmunk | Tamias striatus | 7 | 5 (71.4) | WL4 (3), Type IV (1), WL23 (1) | ||

| Woodchuck | Marmota monax | 5 | 5 (100) | WL4 (2), Type IV + WL20 (1), WL22 (1), WW6 (1) | ||

| Deer mouse | Peromyscus sp. | 55 | 13 (23.6) | WL4 (10), WL23 (2), WL25 (1) | ||

| Boreal red-backed vole | Myodes gapperi | 5 | 1 (20) | WL20 + WL21(1) | ||

| Meadow vole | Microtus pennsylvanicus | 10 | 3(33) | Peru11 (1), Peru11 + type IV (1), WL21 + unknown (1) | ||

| Guinea pigs | Cavia porcellus | 60 | 4 (6.7) | Peru 16 (4) | Cama et al., 2007 | |

| Black-tailed prairie dogs | Cynomys ludovicianus | 153 | 14 (9.2) | Row (14) | ||

| Poland | Pallas | Apodemus agrarius | 184 | 79a | D (6), WR8 (2), WR5 (1), WR7 (1), gorilla 1 (1) | Perec-Matysiak et al., 2015 |

| Yellow-necked mouse | Apodemus flavicollis | 60 | 18a | D (2), WR6 (6), WR4 (1), WR1 (1), WR9 (1) | ||

| Bank vole | Myodes glareolus | 46 | 18a | D (2), WR6 (2), WR10 (2), WR2 (1) | ||

| House mouse | Mus musculus | 21 | 6a | WR3 (1) | ||

| Slovakia | House mouse | Mus musculus musculus | 280 | 3 (1.1) | Unknown | Danišová et al., 2015 |

| China | Chinchillas | Chinchilla lanigera | 140 | 5 (3.6) | D (2), BEB6 (3) | Qi et al., |

| Brown rats | Rattus norvegicus | 242 | 19 (7.9) | D (17), Peru6 (2) | Zhao et al., 2018 | |

| Red-bellied tree squirrels | Callosciurus erythraeus | 144 | 24 (16.7) | D (18), EbpC (3), SC02 (1), CE01 (1), CE02 (1) | Deng et al., 2016 | |

| Chipmunks | Eutamias asiaticus | 279 | 49 (17.6) | D (6), SCC-1 (17), SCC-2 (9), SCC-3 (5), CHY1 (5), Nig 7 (4), CHG9 (2), SCC-4 (1) | Deng et al., 2018a |

aRepresents positive samples in feces and spleen.

Previous studies have indicated that five Cryptosporidium species and nine Cryptosporidium genotypes exist in various rodents in China (Table 3)12,22,23. In this study, five different Cryptosporidium species/genotypes were identified, including Cryptosporidium rat genotypes I and II, Cryptosporidium ferret genotype, Cryptosporidium chipmunk genotype III, and C. parvum. Cryptosporidium rat genotypes I and II have been found in brown rats in the Philippines34, Nigeria20, Australia35, and China22, even in South Nation River watershed, raw wastewater, and environmental samples in the United Kingdom, Canada, and China36–38. Cryptosporidium ferret genotype has been found in ferrets and red squirrels in Italy39. The Cryptosporidium chipmunk genotype III was previously reported in red squirrels, eastern squirrels, eastern chipmunks, and deer mice in the USA40. To date, little is known regarding the disease-causing potential of the four genotypes in humans and livestock; thus bringing attention to the need for epidemiological molecular surveillance of Cryptosporidium spp. for the assessment of infectivity across different hosts.

C. parvum is one of the two predominant Cryptosporidium species in humans41. C. parvum has been identified in humans in Henan province, China42. Moreover, C. parvum infections have been observed in brown rats in Japan, mice and red-backed voles in the USA, brown rats in Iran, striped field mice in Slovak Republic, and hamsters, Siberian chipmunks, chinchillas, and Bamboo rats in China, highlighting the prevalence of C. parvum in rodents (Table 3)12,25,27. In addition, C. parvum has also been found in other animals, such as cattle, sheep, goats, deer, alpacas, horses, dogs, gray wolves, raccoon dogs, cats, and pigs43,44. In this study, only two C. parvum isolates were identified in investigated red squirrels; however, these isolates may result in emerging zoonotic infections through the oral-fecal route.

Three known genotypes (D, SCC-2, and SCC-3) and two novel genotypes (RS01 and RS02) were identified in this study. Genotype D was the predominant genotype (44.3%, 27/61). This finding was similar to previous reports in mice in Czech Republic and Germany45 (32.3%, 10/31), mice in Poland46 (33.3%, 10/30), and brown rats (89.5%, 17/19) and red-bellied tree squirrels (75%, 18/24) in China12,18. In China, genotype D has been identified in humans and various animals, such as nonhuman primates, cattle, sheep, horses, pigs, dogs, cats, and in wastewater14,47–49. This study demonstrated the presence of genotype D in red squirrels for the first time, suggesting that red squirrels could play a potential role in the disease dissemination of E. bieneusi to humans.

Conclusions

This is the first report on the incidence of Cryptosporidium spp. and E. bieneusi in pet red squirrels in China. The infection rates of Cryptosporidium spp. and E. bieneusi were 8.6% and 19.4%, respectively. The detection of zoonotic C. parvum and genotype D of E. bieneusi suggests that red squirrels are a potential source of cryptosporidiosis and microsporidiosis in humans. However, the infection sources and transmission dynamics between red squirrels and humans remain unknown, thus emphasizing on the importance of further follow-up studies of the transmission dynamics of these pathogens.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

The present study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee and the Animal Ethical Committee of Sichuan Agricultural University, and all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Permission was obtained from the owners or shop managers before the fecal specimens were collected.

Collection of specimens

A total of 314 fecal specimens were collected from red squirrels from four pet shops (n = 269) and owners (n = 45) in the Sichuan province, southwestern China between September 2016 and December 2017 (Table 1). All tested pet shops only raised red squirrels and served as suppliers of red squirrels to other pet shops. Sample size was approximately 20% of the squirrels from each shop, and small-scale shops (population less than 50) were not included. The four pet shops are distributed in Jianyang (104°32′E, 30°24′N), Pengzhou (103°57′E, 30°59′N), Wenjiang (103°51′E, 30°40′N), and Jintang (104°24′E, 30°51′N). Pet squirrels from owners were primarily distributed around the urban areas of Chengdu city (104°03′E–104°08′E, 30°36′N–30°52N′). In both pet shops and homes, red squirrels were housed in separate cages. Approximately 30–50 g fresh fecal samples were collected from the bottom of each cage after defecation using a sterile disposal latex glove and then immediately placed into individual disposable plastic bags. No obvious clinical signs were observed at the time of sampling, and the age, sex, and source were recorded at the same time. All fecal specimens were stored in 2.5% potassium dichromate solution at 4 °C until processing.

DNA extraction

The fecal specimens were washed three times in distilled water with centrifugation at 3,000 × g for 10 min to remove the potassium dichromate. Genomic DNA was extracted from approximately 200 mg of each processed fecal specimen using an E.Z. N. A. R Stool DNA kit (Omega Biotek Inc., Norcross, GA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s recommended instructions. The extracted DNA was stored at −20 °C until molecular analysis.

Genotyping of Cryptosporidium spp. and E. bieneusi

Cryptosporidium spp. were identified by nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of an SSU rRNA gene fragment of ~830 bp designed by Xiao et al.50. E. bieneusi genotypes were determined by nested PCR amplification of a 392-bp fragment containing the entire ITS (243 bp) and portions of the flanking large and small subunits of the rRNA gene31 (Supplementary Table 1). TaKaRa Taq DNA Polymerase (TaKaRa Bio, Otsu, Japan) was used for PCR amplification. Positive controls (camel-derived C. andersoni DNA for Cryptosporidium spp. and horse-derived genotype D DNA for E. bieneusi) and negative control with no DNA added were included in all PCR assays. The secondary PCR products were examined by agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized after ethidium bromide staining.

Sequence analysis

All nested PCR positive-products were sequenced using the same PCR primers as those used for the secondary PCRs on an ABI 3730 instrument (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) at the BioSune Biotechnology Company (Shanghai, China). The nucleotide sequences of each obtained gene were aligned and analyzed using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool and Clustal X (http://www.clustal.org/) with reference sequences retrieved from GenBank to identify Cryptosporidium spp. and E. bieneusi genotypes.

Phylogenetic analyses

To support the Cryptosporidium species/genotypes and assess the genetic relationships between the E. bieneusi genotypes in the present study and reference sequences previously published in GenBank, phylogenetic analysis was performed using Phylip version 3.69 package and by constructing a neighboring-joining tree using Mega 6 software (http://www.megasoftware.net/), which is based on evolutionary distances calculated using a Kimura 2-parameter model. The MegAlign program in the DNA Star software package (version 5.0) was used to determine the degree of sequence identity. The reliability of these trees was assessed using bootstrap analysis with 1,000 replicates.

Statistical analysis

Variations in the occurrence of Cryptosporidium spp. (y1) and E. bieneusi (y2) in red squirrels according to age (x1), sex (x2), and geographical location (x3) were analyzed by χ2 test using SPSS V20.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA). Each of these variables was included in the binary logit model as an independent variable by multivariable regression analysis. When the P value was less than 0.05, the results were considered statistically significant. The adjusted odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for each variable were calculated with binary logistic regression, and all risk factors were entered simultaneously.

GenBank accession numbers

Representative nucleotide sequences were deposited in GenBank with the following accession numbers: MH940281-MH940290.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank Xiaolong Huang and Bo Bi for collecting samples. The study was financially supported by the National Science and Technology Department “13th five-year” Special Subproject of China (No. 2016YFD0501009) and the Chengdu Giant Panda Breeding Research Foundation (CPF2017-12, CPF2015-09, CPF2015-07).

Author contributions

L.D. designed the project, performed experiments and discussed the data. Y.C. performed experiments and analyzed the data. R.L. analyzed and discussed the data. L.Y. collected the fecal samples. J.Y. collected the fecal samples. Z.Z. designed the project and analyzed the data. W.W. collected the fecal samples. L.X. performed experiments. H.F. analyzed and discussed the data. H.L. analyzed the data. Z.Z. designed the project. C.Y. collected the fecal samples. W.C. designed the project. G.P. designed the project and analyzed and discussed the data. All authors prepared final manuscript.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its Supplementary Information Files.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Lei Deng, Yijun Chai and Run Luo.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-57896-w.

References

- 1.Wang L, et al. Zoonotic Cryptosporidium species and Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotypes in HIV-positive patients on antiretroviral therapy. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2013;51:557–563. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02758-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xiao L. Molecular epidemiology of cryptosporidiosis: an update. Exp. Parasitol. 2010;124:80–89. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2009.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Santín M, Fayer R. Microsporidiosis: Enterocytozoon bieneusi in domesticated and wild animals. Res. Vet. Sci. 2011;90:363–371. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2010.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ryan U, Fayer R, Xiao L. Cryptosporidium species in humans and animals: current understanding and research needs. Parasitol. 2014;141:1667. doi: 10.1017/S0031182014001085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Didier ES, Weiss LM. Microsporidiosis: current status. Cur Opin. Infect. Dis. 2006;19:485. doi: 10.1097/01.qco.0000244055.46382.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xiao L, Feng Y. Zoonotic cryptosporidiosis. Pathog. Dis. 2010;52:309–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2008.00377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lobo ML, et al. Cryptosporidium spp., Giardia duodenalis, Enterocytozoon bieneusi and Other Intestinal Parasites in Young Children in Lobata Province, Democratic Republic of São Tomé and Principe. PLoS One. 2014;9:e97708. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao W, et al. Genotyping of Enterocytozoon bieneusi (Microsporidia) isolated from various birds in China. Infect. Gene Evol. 2016;40:151–154. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2016.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.NIAID Emerging Infectious Diseases/Pathogens (2015).

- 10.Karim MR, et al. Multilocus sequence typing of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in nonhuman primates in China. Vet. Parasitol. 2014;200:13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zheng, S. et al. Molecular identification and epidemiological comparison of Cryptosporidium spp. among different pig breeds in Tibet and Henan, China. BMC Vet. Res. 15 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Zhao, W. et al. Molecular characterizations of Cryptosporidium spp. and Enterocytozoon bieneusi in brown rats (Rattus norvegicus) from Heilongjiang Province, China. Parasit Vectors11 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Li W, Feng Y, Santin M. Host Specificity of Enterocytozoon bieneusi and Public Health Implications. Trends Parasito. 2019;35:436–451. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2019.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang, S. S. et al. Prevalence and genotypes of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in China. Acta. Trop183 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Yang Z, et al. Molecular detection and genetic characterizations of Cryptosporidium spp. in farmed foxes, minks, and raccoon dogs in northeastern China. Parasitol. Res. 2018;117:169–175. doi: 10.1007/s00436-017-5686-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qi M, et al. Zoonotic Cryptosporidium spp. and Enterocytozoon bieneusi in pet chinchillas (Chinchilla lanigera) in China. Parasitol. Int. 2015;64:339–341. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2015.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deng L, et al. Molecular characterization and new genotypes of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in pet chipmunks (Eutamias asiaticus) in Sichuan province, China. Bmc Microbiol. 2018;18:37. doi: 10.1186/s12866-018-1175-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deng L, et al. First Report of the Human-Pathogenic Enterocytozoon bieneusi from Red-Bellied Tree Squirrels (Callosciurus erythraeus) in Sichuan, China. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0163605. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cama VA, et al. Transmission of Enterocytozoon bieneusi between a child and guinea pigs. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2007;45:2708. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00725-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ayinmode AB, Ogbonna NF, Widmer G. Detection and molecular identification of Cryptosporidium species in laboratory rats (Rattus norvegicus) in Ibadan, Nigeria. Ann. Parasitol. 2017;63:105. doi: 10.17420/ap6302.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gholipoury M, Rezai HR, Namroodi S, Arab KF. Zoonotic and Non-zoonotic Parasites of Wild Rodents in Turkman Sahra, Northeastern Iran. Iran. J. Parasitol. 2016;11:350–357. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lv C, et al. Cryptosporidium spp. in Wild, Laboratory, and Pet Rodents in China: Prevalence and Molecular Characterization. Appl. Env. Microbiol. 2009;75:7692. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01386-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu X, et al. Occurrence of novel and rare subtype families of Cryptosporidium in bamboo rats (Rhizomys sinensis) in China. Vet. Parasitol. 2015;207:144–148. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2014.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu X, et al. Emergence of Cryptosporidium hominis Monkey Genotype II and Novel Subtype Family Ik in the Squirrel Monkey (Saimiri sciureus) in China. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0141450. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kimura A, et al. Detection and genotyping of Cryptosporidium from brown rats (Rattus norvegicus) captured in an urban area of Japan. Parasitol. Res. 2007;100:1417. doi: 10.1007/s00436-007-0488-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ziegler PE, Wade SE, Schaaf SL, Chang YF, Mohammed HO. Cryptosporidium spp. from small mammals in the New York City watershed. J. Wildl. Dis. 2007;43:586. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-43.4.586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Danišová O, et al. Rodents as a reservoir of infection caused by multiple zoonotic species/genotypes of C. parvum, C. hominis, C. suis, C. scrofarum, and the first evidence of C. muskrat genotypes I and II of rodents in Europe. Acta Trop. 2017;172:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2017.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roellig DM, et al. Identification of Giardia duodenalis and Enterocytozoon bieneusi in an epizoological investigation of a laboratory colony of prairie dogs, Cynomys ludovicianus. Vet. Parasitol. 2015;210:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2015.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guo Y, et al. Host specificity and source of Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotypes in a drinking source watershed. Appl. Environl. Microbiol. 2014;80:218–225. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02997-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Danišová O, Valenčáková A, Stanko M, Luptáková L, Hasajová A. First report of Enterocytozoon bieneusi and Encephalitozoon intestinalis infection of wild mice in Slovakia. Ann. Agricul Env. Med. Aaem. 2015;22:251–252. doi: 10.5604/12321966.1152075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sulaiman IM, et al. Molecular Characterization of Microsporidia Indicates that Wild Mammals Harbor Host-Adapted Enterocytozoon spp. as well as Human-Pathogenic Enterocytozoon bieneusi. Appl. Env. Microbiol. 2003;69:4495. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.8.4495-4501.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang, C. et al. Environmental Transport of Emerging Human-Pathogenic Cryptosporidium Species and Subtypes through Combined Sewer Overflow and Wastewater. Appl. Environ. Microbiol., AEM. 00682–00617 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Yamashiro S, et al. Enterocytozoon bieneusi detected by molecular methods in raw sewage and treated effluent from a combined system in Brazil. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 2017;112:403–410. doi: 10.1590/0074-02760160435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nghublin JS, Singleton GR, Ryan U. Molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium spp. from wild rats and mice from rural communities in the Philippines. Infect. Gene. Evol. 2013;16:5. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koehler AV, Wang T, Haydon SR, Gasser RB. Cryptosporidium viatorum from the native Australian swamp rat Rattus lutreolus -An emerging zoonotic pathogen? Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2018;7:18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ijppaw.2018.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jiang J, Alderisio KA, Xiao L. Distribution of cryptosporidium genotypes in storm event water samples from three watersheds in New York. Appl. Env. Microbiol. 2005;71:4446. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.8.4446-4454.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chalmers RM, et al. Detection of Cryptosporidium species and sources of contamination with Cryptosporidium hominis during a waterborne outbreak in north west Wales. J. Water Health. 2010;8:311–325. doi: 10.2166/wh.2009.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Feng Y, Li N, Duan L, Xiao L. Cryptosporidium Genotype and Subtype Distribution in Raw Wastewater in Shanghai, China: Evidence for Possible Unique Cryptosporidium hominis Transmission. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2009;47:153. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01777-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kvác M, et al. Natural infection with two genotypes of Cryptosporidium in red squirrels (Sciurus vulgaris) in Italy. Folia. Parasitol. 2008;55:95–99. doi: 10.14411/fp.2008.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Feng Y, et al. Cryptosporidium Genotypes in Wildlife from a New York Watershed. Appl. Env. Microbiol. 2007;73:6475. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01034-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Essid R, Menotti J, Hanen C, Aoun K, Bouratbine A. Genetic diversity of Cryptosporidium isolates from human populations in an urban area of Northern Tunisia. Infect. Gene Evol. 2018;58:237–242. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2018.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang R, et al. Genetic characterizations of Cryptosporidium spp. and Giardia duodenalis in humans in Henan, China. Exp. Parasitol. 2011;127:42–45. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2010.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang XX, et al. First report of Cryptosporidium canis in farmed Arctic foxes (Vulpes lagopus) in China. Parasit. Vectors. 2016;9:1–4. doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-1291-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang R, et al. Prevalence and molecular identification of Cryptosporidium spp. in pigs in Henan, China. Parasitol. Res. 2010;107:1489–1494. doi: 10.1007/s00436-010-2024-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sak B, Kváč M, Květoňová D, Albrecht T, Piálek J. The first report on natural Enterocytozoon bieneusi and Encephalitozoon spp. infections in wild East-European House Mice (Mus musculus musculus) and West-European House Mice (M. m. domesticus) in a hybrid zone across the Czech Republic-Germany border. Vet. Parasitol. 2011;178:246–250. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Perec-Matysiak A, et al. Diversity of Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotypes among small rodents in southwestern Poland. Vet. Parasitol. 2015;214:242–246. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2015.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yue, D. M. et al. Occurrence of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in Donkeys (Equus asinus) in China: A Public Health Concern. Front Microbiol. 8 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Karim MR, et al. Genetic polymorphism and zoonotic potential of Enterocytozoon bieneusi from nonhuman primates in China. Appl. Env. Microbiol. 2014;80:1893. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03845-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li W, et al. High diversity of human-pathogenic Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotypes in swine in northeast China. Parasitol. Res. 2014;113:1147–1153. doi: 10.1007/s00436-014-3752-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xiao L, et al. Phylogenetic analysis of Cryptosporidium parasites based on the small-subunit rRNA gene locus. Appl. Env. Microbiol. 1999;65:1578. doi: 10.1128/AEM.65.4.1578-1583.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its Supplementary Information Files.