Abstract

Psychological abuse within intimate relationships is linked to negative health outcomes among women and is frequently identified as more wounding than physical or sexual violence. There is little agreement, however, on how to conceptualize or measure the phenomenon, despite measurement being necessary to estimate the prevalence of psychological abuse, establish its interaction with physical and sexual violence, assess its health impacts, and monitor progress towards global Sustainable Development Goals. To address this gap, we used latent class analysis (LCA), psychometric testing, and logistic regression to evaluate the construct and content validity of alternative methods for deriving a measure of psychological partner abuse, using pooled data from the first 10 countries and 15 sites of the World Health Organization Multi-Country Study on Domestic Violence and Women's Health (WHO MCS). Our analysis finds that psychological abuse is highly prevalent, ranging from 12% to 58% across countries. A three-class solution was supported for coding psychological abuse: none, moderate-intensity abuse, and high-intensity abuse. This three-level categorization, which can be coded without LCA, demonstrates a clear graded relationship with controlling behaviors and all measured health outcomes except physical pain. Factor analysis confirms that psychological abuse and male controlling behaviors are separate constructs as measured in the WHO MCS and the Demographic and Health Surveys and should not be combined. We conclude that this is a simple way to code psychological abuse for cross-country comparison. Its use could support urgently needed research into psychological abuse across settings and identify an appropriate threshold for defining psychological violence for surveys globally.

Keywords: Psychological abuse/violence, Emotional abuse/violence, Intimate partner violence (IPV), Measurement

1. Introduction

Over two decades of research documents consistent associations between intimate partner violence (IPV) and negative physical and mental health outcomes for women (Mary Ellsberg, Jansen, Heise, Watts, & Garcia-Moreno, 2008; World Health Organization, 2013). Although most extant research has focused on the prevalence and consequences of physical and sexual partner violence, women frequently report that psychological or emotional abuse (hereafter used interchangeably) can be even more damaging (Diane R Follingstad, 2009) and studies have linked psychological abuse alone to many mental, physical, and functional limitations in a range of settings (Ludermir, Lewis, Valongueiro, Araújo, & Araya, 2010; Porcerelli, West, Binienda, & Cogan, 2006; Ruiz-Perez & Plazaola-Castano, 2005; Yoshihama, Horrocks, & Kamano, 2009). These findings prompted a 2010 Lancet commentary calling for a “radical re-evaluation of the importance of emotional abuse in women's health” (Jewkes, 2010).

Currently, a number of large-scale, population-based, cross-cultural surveys—including the World Health Organization Multi-Country Study on Domestic Violence and Women's Health (WHO MCS) and the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS)—collect data on psychologically abusive acts. However, there has been little progress in reaching consensus on how to conceptualize and measure psychological violence. Investigators have coded items differently, applying various cut-points based on frequency, number or types of acts, or combining measures of psychological abuse with measures of male controlling behaviors. This confounds discrimination of low-level tactics from more intense behaviors as well as the differential impact of separate but related constructs.

The challenge of defining a threshold for psychological violence is a long-standing concern. Over a decade ago, the authors of the original WHO MCS report refrained from publishing prevalence estimates of psychological violence because of concerns about a lack of cross-cultural consensus on what constitutes this phenomenon (Garcia-Moreno, Jansen, Ellsberg, Heise, & Watts, 2005). They highlighted the need for methodological progress toward defining and operationalizing psychological abuse, a need that has been recently heightened by the inclusion of IPV (physical, sexual, and/or psychological) as an indicator for Goal 5 (Gender Equality and Women and Girls’ Empowerment) of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)—a set of global objectives for improving the health and well-being of the planet and its inhabitants by 2030 (United Nations, 2015). Standardized measures for physical and sexual violence already exist but baselines cannot be established, and progress cannot be monitored without similar standard measures for psychological violence.

In the absence of consensus on a cross-cultural definition of psychological violence or even what distinguishes the occasional unkind word from clinically relevant abuse, we propose leveraging the use of existing data on emotionally abusive acts to approximate levels of psychological abuse by an intimate partner. To this end, we use data from the WHO MCS to: 1) examine the patterning of items measuring psychological aggression in the ten original WHO MCS countries to provide insight into potential cut-points; 2) use latent class analysis to identify gradations of psychological abuse and violence; 3) test the convergent and construct validity of this modelling approach; and 4) propose coding for analyzing these data until better measures are developed.

2. Methods

2.1. Data collection procedures

The WHO MCS is a probability-based household survey originally conducted between 2000 and 2004 among women at 15 sites in 10 countries (Bangladesh, Brazil, Ethiopia, Japan, Namibia, Peru, Samoa, Serbia and Montenegro, Thailand, and United Republic of Tanzania)(Garcia-Moreno et al., 2005). For most sites, a two-stage cluster sampling design was used to select households. Within each household only one female occupant between the ages of 15 and 49 years (18–49 years in Japan) was invited to participate. Response rates exceeded 85% in all sites except for Japan, where the response rate was 60% (Claudia Garcia-Moreno et al., 2005). In total, 24 097 women were interviewed.

Investigators used a variety of techniques to maximize disclosure and comparability among settings (Jansen et al., 2004), special ethical and safety procedures were followed, and the study received ethical clearance from the WHO Secretariat Committee for Research in Human Subjects as well as all relevant country-level ethics committees (Watts, Heise L, Elisberg M, 1999). Further methodological details are available in the original WHO publication (Claudia Garcia-Moreno, Jansen, Ellsberg, Heise, & Watts, 2006). The present analysis is restricted to women who had ever had an intimate male partner (N = 19 567).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Intimate partners’ psychological abuse

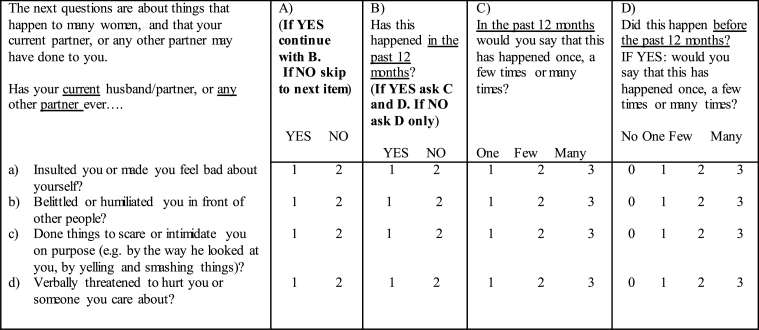

The WHO MCS Study questionnaire included four questions on psychologically abusive behaviors. A list of possible questions was identified from the international literature, with a preference for cross-cultural studies (Ramiro, Hassan, & Peedicayil, 2004; Yoshihama et al., 2009). Initial selection was made at a meeting attended by investigators from all ten participating countries, and selected items were pilot tested in 5 of the 10 countries (Bangladesh, Brazil, Peru, Japan, and Tanzania) and subsequently reviewed by local advisory committees composed of researchers, health professionals, and activists working in the field of gender-based violence. The questions were finalized after piloting and review by global and national teams of researchers who corroborated that they covered prominent, contemporary, psychological abuse constructs that were similarly salient across all settings (Sackett & Saunders, 1999; Tolman, 1999). Respondents were asked whether they had ever experienced each of the four types of acts (see Fig. 1), and if yes, whether they experienced it within the last 12 months and with what frequency: once, a few times, or many times (C Garcia-Moreno et al., 2006).

Fig. 1.

Emotional/psychological abuse questions in the world health organization multi-country study on domestic violence and Women's health.

A common approach to summarizing the phenomenon of psychological abuse is to consider a person to have been psychologically or emotionally maltreated if she answers affirmatively to any one item at any frequency. However, doing so lumps together very diverse experiences, not all of which may be considered clinically meaningful given the lack of an agreed upon threshold for defining psychological “abuse” or “violence” (Diane R Follingstad, 2009). Alternatively, a psychological violence score is often created by summing across the items and frequencies in a manner similar to the scoring convention of the revised Conflicts Tactics Scales (Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996). A total score, however, does not provide guidance on meaningful cut-points that might be consistently applied to measure thresholds for harm and potential change over time. In order to condense the data for the purpose of analysis, the frequency was recategorized for each item as not occurring, infrequently occurring (once, few times), and frequently occurring (many times).

The Cronbach's alpha for the scale, estimated across the pooled sample, was 0.78. Polychoric correlations among the four variables ranged from 0.68 to 0.81. The Cronbach's alphas for each individual country were as follows: Bangladesh, 0.78; Brazil, 0.83; Ethiopia, 0.65; Japan, 0.64; Namibia, 0.83; Peru, 0.82; Samoa, 0.84; Serbia, 0.80; Thailand, 0.78; Tanzania, 0.80.

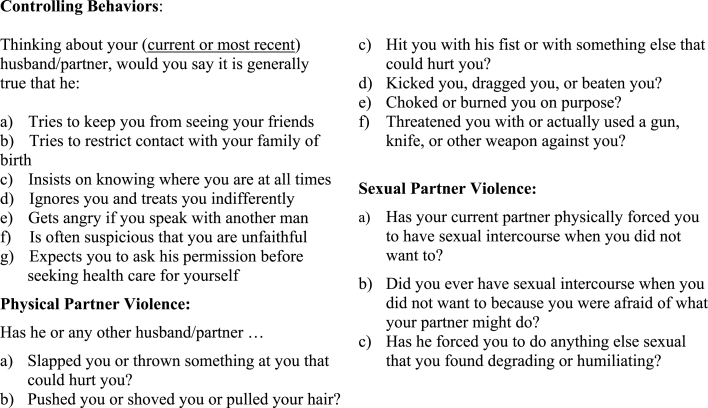

2.2.2. Physical and/or sexual IPV

The WHO MCS study module included six items designed to capture physical violence by intimate partners and three questions on sexual violence by partners [see (Claudia Garcia-Moreno et al., 2006) for details] (see Fig. 2). For each type of violence, the module asked women whether they had ever experienced the act by an intimate partner prior to the interview, and if yes, whether they experienced it within the last 12 months and with what frequency: once, a few times, or many times. Here ever-partnered women who responded yes to any of the specific acts of physical and/or sexual violence were categorized as ever having experienced physical and/or sexual IPV. The pooled Cronbach's alpha for recent (past 12 month) physical and/or sexual IPV was 0.84.

Fig. 2.

Questions on Controlling Behaviors and/or Physical and Sexual Violence by an Intimate Partner from the World Health Organization Multi-Country Study on Domestic Violence and Women's Health.

2.2.3. Intimate partners’ controlling behaviors

The WHO MCS questionnaire included seven questions (see Fig. 2) specifically designed to capture controlling behaviors. These ask about a pattern of behavior (i.e. “Thinking about your current or most recent partner, would you say it is generally true that,” about such items as, “he is often suspicious that you are unfaithful” or “tries to restrict contact with your family of birth.”). Based on the responses to the seven items, we created a variable denoting the intensity of controlling behaviors experienced, by classifying those who reported three or more controlling behaviors to a “high control” group, and those with one or two to a “low control” group, and those reporting no controlling experiences as an “unexposed” group. The pooled Cronbach's alpha for lifetime controlling behaviors was 0.68.

2.2.4. Health status indicators

We assessed self-rated health status by a commonly used single question: “In general would you describe your overall health as excellent, good, fair, poor, or very poor?” We grouped together respondents reporting “poor” and “very poor” health as constituting “poor self-rated health.” This measure of self-reported health status has been found to predict morbidity (Fryers, Melzer, & Jenkins, 2003; Sorlie, Backlund, & Keller, 1995) as well as physical and/or sexual IPV(M. Ellsberg et al., 2008). Four physical symptoms experienced in the four weeks before the interview, including difficulties with walking, daily activities, physical pain, and memory loss, were assessed on a five-point scale from “not occurring” to “extreme” (e.g., unable to walk at all). Each of the symptoms was dichotomized as “poor” if the respondent rated their health with one of the three lowest categories.

We assessed mental health status with the 20-item Self-Reporting Questionnaire (SRQ-20) (Beusenberg & Orley, 1994), dichotomized at greater or equal to eight, among the most frequently used cut-points to indicate mental distress in research in lower income countries(Ali, Ryan, & De Silva, 2016; Beusenberg & Orley, 1994). The pooled Cronbach's alpha for the SRQ-20 was 0.98. Suicidal ideation was assessed with one item from the SRQ-20: “Within the past four weeks, has the thought of ending your life been on your mind?” Elevated odds of suicidal ideation either in the past four weeks or ever have been associated with experiences of physical and sexual IPV in both the WHO MCS Study and elsewhere (Mary Ellsberg et al., 2008; Ruchira Tabassum & Nazneen, 2008; Vizcarra et al., 2004).

2.2.5. Additional covariates

Additional covariates include marital status, age, socioeconomic status, level of education, parity, childhood sexual abuse (experience of unwanted sexual experiences before age 15 years), and family history of IPV (respondent reported mother's physical abuse by an intimate partner).

2.3. Analytic approach

Exploratory factor analysis was used in a random half of the sample followed by a confirmatory factor analysis in the remaining half to assess the appropriateness of combining controlling behavior items with those on psychological abuse. Frequency and types of the four emotionally abusive behaviors were examined by country, and latent class analysis (Collins & Lanza, 2010) was used to examine patterns of partner violence victimization. First, models of two through four classes were fit separately for each country to examine if the same general latent structure was identified across sites. Differences in the log likelihood, adjusted Bayesian information criterion, and the Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test were used to determine which model fit the data best in each country, and the principle of parsimony was applied(Collins & Lanza, 2010). Entropy and posterior probabilities were examined to ascertain the model's ability to classify the study population into patterns.

Cross tabulations and Chi Square tests were used to assess convergent validity of measures of psychological abuse by examining the degree to which the respondents’ reported level of psychological abuse was associated with physical IPV, sexual IPV, or a high degree of controlling behaviors. Criterion validity was examined using population-averaged logistic regressions to predict the health outcomes, adjusted for potential confounders, and using generalized estimating equations with robust standard errors. All analyses were conducted in STATA version 14.2.

3. Results

The proportion of women experiencing any listed act of psychological abuse within the last year ranged from 12% in Samoa and Serbia and Montenegro to 58% in provincial Ethiopia (Table 1). Supplemental Table S.1 summarizes the proportion of women who have experienced each psychologically abusive act within the last 12 months, by country. In all cases, the most commonly reported act of psychological abuse was “being insulted or made to feel bad about oneself” and the least frequent act was “threatening to harm you or someone you care about.”

Table 1.

Prevalence of emotional aggression in past 12 months among ever-partnered women, by country (N = 19 567).

| Bangladesh | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| No | 2044 | 0.76 |

| Yes | 658 | 0.24 |

| Brazil | ||

| No | 1664 | 0.78 |

| Yes | 464 | 0.22 |

| Ethiopia | ||

| No | 960 | 0.42 |

| Yes | 1301 | 0.58 |

| Japan | ||

| No | 1090 | 0.85 |

| Yes | 197 | 0.15 |

| Namibia | ||

| No | 1107 | 0.81 |

| Yes | 266 | 0.19 |

| Peru | ||

| No | 1630 | 0.62 |

| Yes | 996 | 0.38 |

| Samoa | ||

| No | 1058 | 0.88 |

| Yes | 148 | 0.12 |

| Serbia and Montenegro | ||

| No | 1054 | 0.88 |

| Yes | 140 | 0.12 |

| Tanzania | ||

| No | 1941 | 0.72 |

| Yes | 771 | 0.28 |

| Thailand | ||

| No | 1662 | 0.80 |

| Yes | 416 | 0.20 |

Results of our factor analysis confirmed that psychological abuse and male controlling behaviors are separate constructs as measured in the WHO MCS, and therefore should not be combined. In the exploratory factor analysis, the two-factor solution (root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA] = 0.065; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.062, 0.068; comparative fit index [CFI] = 0.957) was superior to a one-factor solution (RMSEA = 0.099; 95% CI = 0.096, 0.101; CFI = 0.871), with all of the controlling behavior items loading separately from the psychological items, with the exception of indifference which loaded on both factors. A three-factor model fit better than the two-factor model (RMSEA = 0.030; 95% CI = 0.027, 0.034; CFI = 0.99); however, the third factor was uninterpretable and split the controlling behaviors into two factors. The two-factor model without the indifference item had adequate fit in the CFA (RMSEA = 0.062; 95% CI = 0.060, 0.065; CFI = 0.960), further confirming the lack of a common factor underlying the current iteration of the controlling behavior and emotional abuse items.

Across all countries, a robust three-class model of psychological abuse emerged. A four-class model demonstrated some evidence of good fit, particularly regarding a significant Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test; however, in all of these cases, at least one other indicator also suggested that a three-class model would be preferable (e.g., a larger Bayesian Information Criterion [BIC] in the four-versus the three-class model). Relying on the principle of parsimony, a three-class model was ultimately chosen. Supplemental Table S.2 summarizes the model fit of the pooled analysis and for each country separately. For all countries, a clear pattern emerged based on frequency and type of act. We labelled these high intensity, moderate intensity, and little to no exposure to psychological abuse. Table 2 presents the results for the pooled analysis. Country-specific analyses are available in Supplemental Table S.3.

Table 2.

Item conditional probabilities, pooled analysis (N = 19 526).

| N (%) | None |

Moderate |

High |

|---|---|---|---|

| 17 016 |

1697 |

813 |

|

| 87 | 9 | 4 | |

| Insult | |||

| None | 0.89 | 0.16 | 0.08 |

| Infrequent | 0.09 | 0.68 | 0.05 |

| Frequent | 0.02 | 0.16 | 0.87 |

| Belittle | |||

| None | 0.99 | 0.53 | 0.24 |

| Infrequent | 0.01 | 0.45 | 0.08 |

| Frequent | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.68 |

| Scare | |||

| None | 0.97 | 0.47 | 0.25 |

| Infrequent | 0.03 | 0.48 | 0.14 |

| Frequent | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.61 |

| Threaten | |||

| None | 1.00 | 0.76 | 0.51 |

| Infrequent | 0.01 | 0.22 | 0.17 |

| Frequent | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.33 |

The high-intensity category was characterized by a high probability of endorsing at least one of the items frequently. The moderate-intensity category was characterized by some exposure across items, but none frequently, except for insults which occasionally appeared “many times.” The final category, little to no exposure, was characterized by almost no exposure to any of the items. This patterning suggested the following categorization: high-intensity exposure, defined as any endorsement of one of the four psychological abuse items as “many times”; no exposure, defined as no exposure to belittling, scaring, or threatening behavior; and moderate-intensity exposure, which included all other combinations. Overall, 14.03% (N = 709) of respondents experienced high-intensity psychological abuse, 9.79% (N = 1911) experienced moderate-intensity psychological abuse, and 83.03% (N = 16 212) experienced little to no psychological abuse. Sample coding for this classification in STATA software is available in Web Appendix A.

Using this categorization, we examined psychological abuse in relation to experiencing controlling behaviors from a partner or ex-partner. In a pooled analysis, a gradient was detectable across the psychological abuse categories in the percent who also experienced controlling behaviors and physical or sexual IPV (Table 3). Similarly, in the generalized estimating equation models adjusted for relevant potential confounders, using the categories derived from the factor analysis demonstrated a dose-response relationship with psychological abuse to all of the health behaviors except for physical pain (Table 4), supporting the criterion validity of the scale.

Table 3.

Experience of controlling behaviors, by emotional abuse level (N = 19 526).

| Control |

Emotional Aggression |

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

None |

Moderate |

High |

|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| None | 6990 | 412 | 154 |

| 43.12 | 21.56 | 10.98 | |

| Low | 6026 | 637 | 374 |

| 37.17 | 33.33 | 26.66 | |

| High | 3196 | 862 | 875 |

| 19.71 | 45.11 | 62.37 | |

Note: Chi Square P value < .001.

Table 4.

Association between psychological abuse intensity and selected health outcomes among ever-partnered women.

|

General Health |

Problems Walking |

Difficulties With Daily Activities |

Problems With Memory or Concentration |

Physical Pain |

Mental Distress (SRQ score ≥8) |

Suicidal Ideation |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

(Poor or Very Poor) | |||||||

| aOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | Beta (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | |

| None | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref |

| Moderate | 1.26 (1.07, 1.48)** | 1.21 (1.04, 1.40)* | 1.39 (1.21, 1.59)*** | 1.49 (1.31, 1.70)*** | 1.34 (1.19, 1.50)*** | 1.80 (1.60, 2.02)*** | 1.91 (1.58, 2.30)*** |

| High | 1.86 (1.58, 2.18)*** | 1.52 (1.29,1.81)*** | 1.72 (1.46, 2.01)*** | 2.03 (1.71, 2.42)*** | 1.22 (1.06, 1.41)** | 2.27 (1.80, 2.84)*** | 3.27 (2.66, 4.01)*** |

| N | 18 930 | 16 887 | 16 896 | 16 897 | 16 894 | 18 943 | 18 927 |

Abbreviations: aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; IPV, intimate partner violence; SRQ, Self-Reporting Questionnaire.

All models adjusted for lifetime IPV (physical/sexual), age, socioeconomic status (SES), education, marital status, parity, childhood sexual abuse, and family history of IPV.

*P ≤ .05 **P ≤ .01 ***P ≤ .001.

4. Discussion

This paper represents an effort to guide future use of the questions pertaining to psychologically abusive acts as measured in the WHO MCS questionnaire. In the absence of contextual data or greater understanding of psychological abuse cross-culturally, we chose to view varying degrees of psychological abuse as a continuum rather than presume a threshold, classifying respondents into three intensity groups based on a combination of the types of acts they experienced and their frequency. These analyses support the validity of this intensity-based approach, showing dose-response relationships between intensity of psychological abuse and negative health indicators. Therefore, we argue for adopting this scheme using WHO MCS data or similar act-based instruments.

This paper's substantive findings on the relationship between psychological abuse and women's self-rated health and suicidal ideation are consistent with previous research that has shown a significant correlation between psychological abuse—either alone or in combination with physical and sexual violence—and various physical and mental health problems (Mary Ellsberg et al., 2008). The fact that the effect persists even after controlling for physical or sexual partner violence adds to the literature suggesting that emotional abuse alone may have detrimental effects on women's health and well-being (A B Ludermir, Schraiber, D'Oliveira, Franca-Junior, & Jansen, 2008; Ruiz-Perez & Plazaola-Castano, 2005; Wagner & Mongan, 1998; Yoshihama et al., 2009). However, because the dominant pattern across settings is that psychological abuse occurs in concert with physical and sexual violence, we suggest that countries using WHO or DHS data to monitor SDGs, report the proportion of women experiencing high-intensity psychological abuse only (i.e., without physical or sexual violence) in the past 12 months as the measure of psychological partner violence. Standardized measures of sexual or physical partner violence will capture most other women experiencing psychological abuse.

In order to further advance measurement and understanding of psychological abuse cross-culturally, it is essential that researchers continue to pursue coordinated research to refine measures of psychological abuse, including efforts to identify an appropriate cut-point between low-grade aggressive acts and frank abuse. This demands further qualitative research to understand how women experience different acts, the meanings they hold in different cultures, the context and events surrounding the acts, and the emotional or physical responses following the experience. This qualitative work must be complemented with further quantitative studies that go beyond population-based studies. Populations seeking clinical or social services as well as service providers are critical for testing instruments and improving understanding of clinical thresholds of psychological abuse.

4.1. Limitations

We acknowledge several limitations of our data and analyses. The cross-sectional design of the WHO MCS limits conclusions about temporality, although the use of indicators of current health substantiates assumptions that psychological abuse preceded or was concurrent with measured outcomes. All measures are based on self-report and are therefore vulnerable to imprecise recall, recall bias, and social desirability bias. Measures of frequency were limited to maximize response rates and respondents’ ability to discriminate among categories (Chachamovich, Fleck, & Power, 2009), which may lead to some misclassification bias. Further, although the questions used here are the most commonly used in this domain, the range of acts assessed by the WHO MCS only taps into a few facets of a multifaceted phenomenon(D R Follingstad, 2011). Finally, the ideal cut-point for the SRQ-20 likely varies across countries or populations(Ali et al., 2016). For convenience, we chose one commonly used cut-point. This may not be similarly optimal for each sample, but misclassification likely averages out in the pooled sample. Additionally, although more extensive tests of reliability and measurement invariance in the latent classes across countries could be pursued in future research, our aim was the identification of broad, robust classifications likely to hold across diverse country settings.

Further work to define and measure the construct of emotional abuse is needed, especially across countries with differing norms. However, this study highlights the validity of a simple scoring method for a widely available measure of psychological abuse. The short length of the scale and the ease of scoring make it a feasible construct to include in epidemiologic studies of the health impact of IPV. It is our hope that this analytic approach can inform future research, encourage further investigation of the additive and independent contributions of psychological abuse to women's health, and contribute to progress towards standardized reporting of psychological partner violence.

5. Conclusion

The SDGs require monitoring the prevalence of psychological abuse by intimate partners, but there is no standardized definition or measure of this construct across cultures. Data on acts of psychological/emotional abuse by intimate partners are available from a large number of countries, collected as part of WHO MCS and DHS, but these data remain largely unanalyzed. Our study develops and tests a means to leverage these data to create a cross-cultural measure of psychological violence by intimate partners for global use until better measures are developed. Our results support a graded relationship between various physical and mental health problems and psychological abuse among women. A simple, three-level index can help facilitate comparable reporting across countries, both in research and for monitoring country progress toward achieving the SDGs.

Funding

The authors did not receive any outside funding to support the writing and analysis in this paper.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100377.

Contributor Information

Lori Heise, Email: lheise1@jhu.edu.

Christina Pallitto, Email: pallittoc@who.int.

Claudia García-Moreno, Email: garciamorenoc@who.int.

Cari Jo Clark, Email: cari.j.clark@emory.edu.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data to this article:

References

- Ali G.C., Ryan G., De Silva M.J. Validated screening tools for common mental disorders in low and middle income countries: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2016;11(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beusenberg M., Orley J. World Health Organization; Geneva: 1994. A user's guide to teh self reporting questionnaire (SRQ) [Google Scholar]

- Chachamovich E., Fleck M.P., Power M. Literacy affected ability to adequately discriminate among categories in multipoint Likert Scales. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2009;62(1):37–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins L.M., Lanza S.T. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; Hoboken, New Jersey: 2010. Latent class and latent transition analysis: With applicaitons in the social, behavioral, and health sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Ellsberg M., Jansen H.A.F.M., Heise L., Watts C.H., Garcia-Moreno C. Intimate partner violence and women's physical and mental health in the WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence: An observational study. Lancet. 2008;371(9619):1165–1172. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60522-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follingstad D.R. The impact of psychological aggression on women's mental health and behavior: The status of the field. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2009;10(3):271–289. doi: 10.1177/1524838009334453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follingstad D.R. A measure of severe psychological abuse normed on a nationally representative sample of adults. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2011;26(6):1194–1214. doi: 10.1177/0886260510368157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryers T., Melzer D., Jenkins R. Social inequalities and the common mental disorders: A systematic review of the evidence. Soc Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2003;38:229–237. doi: 10.1007/s00127-003-0627-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Moreno C., Jansen H.A.F.M., Ellsberg M., Heise L., Watts C. WHO; Geneva, Switzerland: 2005. WHO Multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence against women: Initial results on prevalence, health outcomes and women's responses. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Moreno C., Jansen H.A., Ellsberg M., Heise L., Watts C.H. Prevalence of intimate partner violence: Findings from the WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence. Lancet. 2006;368(9543):1260–1269. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69523-8. [pii] 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69523-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen H.A.F.M., Watts C., Ellsberg M., Heise L., Garcia-Moreno C., García-Moreno C. Interviewer training in the WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence. Violence Against Women. 2004;10(7):831–849. [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R. Emotional abuse: A neglected dimension of partner violence. Lancet. 2010;376(9744):851–852. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61079-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludermir A.B., Lewis G., Valongueiro S.A., Araújo T. V. B. de, Araya R. Violence against women by their intimate partner during pregnancy and postnatal depression: A prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2010;376(9744):903–910. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60887-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludermir A.B., Schraiber L.B., D'Oliveira A.F., Franca-Junior I., Jansen H.A. Violence against women by their intimate partner and common mental disorders. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;66(4):1008–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.10.021. [pii] 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porcerelli J., West P., Binienda J., Cogan R. Physical and psychological symptoms in emotionally abuse and non-abuse women. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 2006;19:201–204. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.19.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramiro L., Hassan F., Peedicayil A. Risk markers of severe psychological violence against women: A WorldSAFE multi-country study. Injury Control and Safety Promotion. 2004;11(2):131–137. doi: 10.1080/15660970412331292360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruchira Tabassum N., Nazneen A. Spousal violence against women and suicidal ideation in Bangladesh. Women's Health Issues: Official Publication of the Jacobs Institute of Women’s Health. 2008;18(6):442–452. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Perez I., Plazaola-Castano J. Intimate partner violence and mental health consequences in women attending family practice in Spain. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2005;67(5):791–797. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000181269.11979.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sackett L.A., Saunders D.G. The impact of different forms of pscyhological abuse on battered women: Special Miniseries on Psychological Abuse. Violence & Victims. 1999;14(1):105–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorlie P.D., Backlund E., Keller J.B. US mortality by economic, demographic, and social characteristics: The national longitudinal mortality study. American Journal of Public Health. 1995;85(7):949–956. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.7.949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus M.A., Hamby S.L., Boney-McCoy S., Sugarman D.B. The revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17(3):283–316. [Google Scholar]

- Tolman R.M. The validation of the psychological maltreatment of women inventory. Violence & Victims. 1999;14(1):23–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations . 2015. Transforming our World: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. New York: United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- Vizcarra B., Hassan F., Hunter W.M., Munoz S.R., Ramiro L.S., De Paula C.S. Partner violence as a risk factor for mental health among women from communities in the Philippines, Egypt, Chile and India. Injury Control and Safety Promotion. 2004;11(2):125–129. doi: 10.1080/15660970412331292351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner P., Mongan P. Validating the concept of abuse: Women's perceptions of defining behaviors and the effects of emotional abuse on health indicators. Archives of Family Medicine. 1998;7:25–29. doi: 10.1001/archfami.7.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts C.H., Heise L., Elisberg M., Garcia-Moreno C. Putting Women First: Ethical and safety recommendations for research on domestic violence. Geneva. World Health Organisation. 1999;8422(August):33. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, & South African Medical Research Council; Geneva, Switzerland: 2013. Global and regional estimates of violence against women: Prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshihama M., Horrocks J., Kamano S. The role of emotional abuse in intimate partner violence and health among women in Yokohama, Japan. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(4):647–653. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.118976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.