Abstract

Objectives

To review systematically copper intrauterine device (Cu-IUD) use and HIV acquisition in women.

Methods

We searched Pubmed, Embase and the Cochrane Library between database inception and 26 June 2019 for longitudinal studies comparing incident HIV infection among women using an unspecified IUD or Cu-IUD compared with non-hormonal or no contraceptive users, or hormonal contraceptive users. We extracted information from included studies, assessed study quality, and summarised study findings.

Results

From 2494 publications identified, seven met our inclusion criteria. One randomised controlled trial (RCT), judged “informative with few limitations”, found no statistically significant differences in HIV risk between users of the Cu-IUD and either intramuscular depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA-IM) or levonorgestrel implant. One observational study, deemed “informative but with important limitations”, found no statistically significant difference in HIV incidence among IUD users compared with women who had tubal ligation or who were not using any contraception. Another “informative but with important limitations” observational study found no difference in HIV incidence between Cu-IUD users and DMPA or norethisterone enanthate injectable, or implant users. An RCT considered “unlikely to inform the primary question” also found no difference in HIV risk between Cu-IUD and progestogen-only injectable users. Findings from the other three “unlikely to inform the primary question” cohort studies were consistent with the more robust studies suggesting no increased risk of HIV acquisition among Cu-IUD users.

Conclusion

The collective evidence, including that from a large high-quality RCT, does not indicate an increased risk of HIV acquisition among users of Cu-IUDs.

Keywords: intrauterine devices, human immunodeficiency virus

Key messages.

Seven studies have investigated whether copper intrauterine devices (Cu-IUDs) are associated with an increased risk of women acquiring HIV, including a high-quality randomised controlled trial.

The collective evidence does not indicate an increased risk of HIV acquisition among users of Cu-IUDs.

Introduction

For nearly 30 years, inconsistent evidence from epidemiological observational research has been accumulating that hormonal contraceptives (particularly depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA)-containing injectables) may be associated with an increased risk of women acquiring HIV. In June 2019, the Evidence for Contraceptive Options and HIV Outcomes (ECHO) trial reported HIV incidence rates in users of three common contraceptives: the copper intrauterine device (Cu-IUD), intramuscular DMPA (DMPA-IM) and the levonorgestrel (LNG) implant.1 The ECHO trial sought to address, through randomisation, a key concern with previous observational studies; namely that of possible confounding (the distortion of the true relationship between contraceptive use and HIV acquisition because of a third factor linked to both exposure and outcome), especially in relation to condom use and other sexual behaviours. Cu-IUD users have often been used as a reference group in the observational studies of hormonal contraceptives and HIV risk because of an assumption that Cu-IUDs do not increase the risk. This assumption is supported by a small biological study of genital tract immune cell changes after insertion of a Cu-IUD which did not indicate increased susceptibility to HIV infection.2 Other biological studies have found that copper as a solution3 or filter4 deactivates HIV. It is important to know if Cu-IUDs affect, positively or negatively, the risk of HIV acquisition among users. We report here a systematic review of longitudinal epidemiological studies which have examined the risk of HIV acquisition among users of the Cu-IUD.

Methods

This systematic review adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines.5 We examined two related but slightly different review questions as follows. (1) Among women at risk of HIV (ie, women who are HIV-seronegative at baseline), does use of a Cu-IUD compared with use of another non-hormonal contraceptive method or no contraceptive method increase the risk of HIV acquisition? (2) Among women at risk of HIV (ie, women who are HIV-seronegative at baseline), does use of a Cu-IUD compared with use of a specific hormonal contraceptive method increase the risk of HIV acquisition?

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included studies of women of reproductive age at risk of HIV infection (ie, seronegative for HIV at baseline) that compared incident, laboratory-confirmed HIV infection among women using a Cu-IUD compared with women using a non-hormonal method (eg, condom, sterilisation, fertility awareness-based methods, withdrawal) or no contraception. We also included studies comparing incident HIV infections among users of Cu-IUDs with another specified hormonal contraceptive (eg, DMPA or other injectable, oral contraceptive (OC), ring, patch or implant) users. We included longitudinal studies (observational studies, randomised controlled trials (RCTs) or meta-analyses); cross-sectional studies, letters, narrative reviews, conference abstracts and other non-primary research reports were excluded. We contacted the chief investigators of studies that did not specify the type of IUD (ie, device was simply referred to throughout as 'IUD') used by participants to ascertain whether the usage related to Cu-IUDs rather than LNG-IUDs or inert IUDs (ie, IUDs with no bioactive component)

Search strategy

We searched Pubmed, Embase and the Cochrane Library from database inception to 26 June 2019 (online supplementary appendix 1). We hand-searched reference lists of included studies. All authors screened abstracts and full-text articles using Covidence,6 and conflicts were resolved through discussion. Two authors (KC and AT) also screened all the articles included in a companion review of hormonal contraceptive use and risk of HIV acquisition7 to identify any additional studies that included an IUD-only arm.

bmjsrh-2019-200512supp001.pdf (38.3KB, pdf)

Data extraction, quality assessment and data synthesis

We used a study quality assessment framework modified from that used for a previous review of hormonal contraceptive use and risk of HIV.8 Briefly, studies that failed to adjust for condom use or had unclear exposure measurement were judged to be “unlikely to inform the primary question”. All other studies could be considered to be either “informative but with important limitations” or “informative with few limitations”, depending on the potential for residual or uncontrolled confounding in the studies (online supplementary appendix 2). We abstracted data from all included studies into an evidence table that included information on the study design, population, exposure and comparison groups, results, strengths and weaknesses, and quality. We synthesised the study results narratively; the small number of point estimates for specific comparisons precluded meta-analysis. For studies that reported risk estimates for a hormonal contraceptive method compared with a Cu-IUD, we report the inverse of the risk estimate so that the Cu-IUD is the exposure and the hormonal contraceptive method is the referent group.

bmjsrh-2019-200512supp002.pdf (59.9KB, pdf)

Patient and public involvement

As this analysis was based on published data, patients and the public were not involved in the design of the study.

Results

Description of included studies

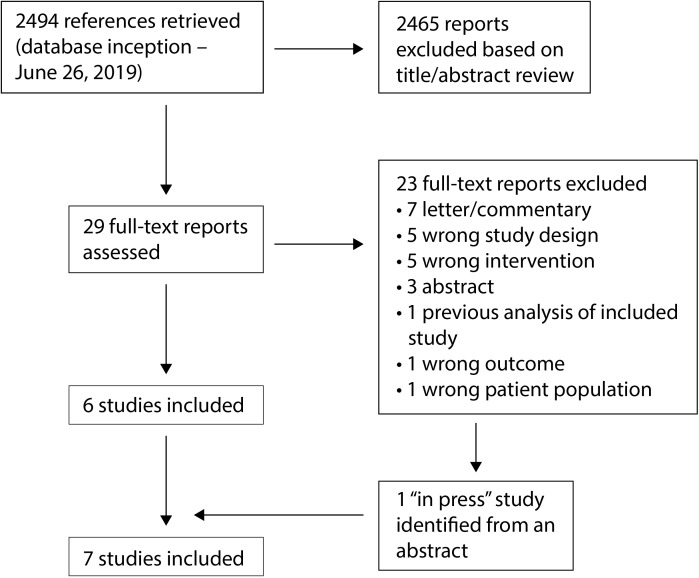

We screened 2494 abstracts and 29 full-text reports (figure 1). We excluded 23 full-text reports – one reported data subsequently updated in a later report, 10 were letters or conference abstracts, and 12 had an irrelevant exposure, outcome, study design or participant group. An 'in press' full report of a new study that has now been published9 was identified from a conference abstract.10 Seven studies met our inclusion criteria (table 1):1 9 11–15 five cohort studies9 11–14 and two RCTs.1 15 The studies were conducted in six countries: Eswatini, Italy, Kenya (three studies), Tanzania, South Africa (three studies) and Zambia. Between 343 and 7830 women were enrolled into the different studies, conducted in a variety of clinical settings: hospital or outpatient clinics serving HIV-infected people, family planning clinics, a clinic for sex workers, hospital-based pregnancy termination services or clinical trial sites for a novel vaginal ring containing dapivirine. Three studies did not specify the type of IUDs that were used.11 12 14 Two of these studies were conducted in Kenya and the study authors confirmed that Cu-IUDs were the type of IUD available during the study.12 14 The third study included two IUD users in Italy;11 the study authors were unable to provide information on the type of IUD used. One study was deemed to be “informative with few limitations”,1 two “informative but with important limitations”,9 14 and four “unlikely to inform the primary question”.11–13 15

Figure 1.

Identification of included studies.

Table 1.

Summary of evidence on intrauterine device use and risk of HIV acquisition in women

| Author, year, location, funding | Study design, purpose, period of data collection | Population | Number seroconverted/number analysed, number of seroconverters by exposure group, overall HIV incidence | Exposure | Comparison | Results (point estimate, CI) | Strengths | Weaknesses | Quality |

| Saracco 1993,11 Italy Ministry of Health and National Research Council of Italy |

Cohort; determine incidence and risk factors for male to female sexual HIV transmission, 1987–1991 | 343 seronegative women with HIV-infected male partners, recruited from 16 hospital and outpatient clinic locations; 529.6 person-years follow-up | 19/343 after mean 14.1 months 1/1 IUD and no condom use seroconverted 0/1 IUD and condom use seroconverted 0/22 OC users seroconverted (11 reported always using condom) 3.6 per 100 person-years |

IUD (type not specified) | No clear comparison group; seroconversions reported for OC users | No comparative estimates given | Serodiscordant couples Study interval 6 months |

No comparative estimates provided and no clear comparison group No adjustment for condom use No time-varying analyses Follow-up rates not reported or unclear |

Unlikely to inform the primary question |

| Sinei 1996,12 Kenya US NIH and USAID, WHO, Ortho Pharmaceutical Corp. |

Cohort; pilot study to examine relationship between contraceptive methods and HIV transmission, 1990–1992 | 1537 seronegative women recruited from a family planning clinic | 16 seroconversions by 12 months: IUD users: 7 DMPA users: 2 OC users: 5 12-month cumulative incidence rates (95% CI) per 100: Overall: 2.1 (95% CI 1.1 to 3.2): IUD: 1.66 (95% CI 0.4 to 2.9) DMPA: 1.92 (95% CI 0.0 to 4.6) OC: 4.45 (95% CI 0.5 to 8.4) |

IUD (type not specified) | No clear comparison group, but separate seroconversion rates provided for DMPA and OC users | No comparative estimates given | Study interval of 3 months | No comparative estimates provided and no clear comparison group No adjustment for condom use No time-varying analyses Low follow-up rates (29% overall) |

Unlikely to inform the primary question |

| Kapiga 1998,13 Tanzania Rockefeller Foundation, US NIH |

Cohort, to study the incidence of HIV associated with contraceptive methods, 1992–1995 | 1370 (of an original cohort of 2471) women recruited from family planning clinics; 2236 person-years follow-up |

75/1370 seroconverted 3.4 per 100 person-years (95% CI 2.6 to 4.1) IUD: 8/162 |

IUD (copper T loop specified); ever-use during the follow-up period | No IUD use (included those using hormonal methods, non-hormonal methods or no method) | IUD use vs no use: adjRR 0.80 (95% CI 0.38 to 1.69) Duration of IUD use 1–12 months vs 0 months: adjRR 1.22 (95% CI 0.44 to 3.37) >13 months vs 0 months: adjRR 0.59 (95% CI 0.21 to 1.66) |

No adjustment for condom use in the main model; authors state in text that results were not materially altered when excluding condom users or adjusting for condom use No time-varying analysis of IUD exposure (exposure measured as ever-use during the follow-up period) Comparison group included all non-IUD users Study interval unclear; HIV testing only occurred at baseline and final interview 44.5% loss to follow-up |

Unlikely to inform the primary question | |

| Lavreys 2004,14 Kenya US NIH |

Cohort, to assess the association between contraceptive use and HIV acquisition, 1993–2003 | 1498 seronegative women, recruited from a clinic for sex workers, Mombasa, 1272 returned for follow-up; providing 2931 person-years follow-up; 15 428 follow-up visits | 248/1272 Number seroconverted by group not reported |

IUD (type not specified) | No contraceptive method or tubal ligation | adjHR 1.1 (95% CI 0.4 to 3.0) | Adjusted for condom use Time-varying analysis of contraception exposure and confounders Clearly defined comparison group Study interval 1 month |

Follow-up rates not reported or unclear Potential for residual confounding |

Informative but with important limitations |

| Hofmeyr 2017,15 South Africa Effective Care Research Unit, East London, South Africa |

RCT; to compare rates of incident HIV among women using progestogen-only injectables and those using Cu-IUDs; 2009–2012 | 2493 enrolled, 1246 in injectable arm and 1247 in IUD arm, recruited from women attending pregnancy termination services at two hospitals in South Africa | ITT analysis 20/656 (3%) injectable arm 22/634 (3.5%) IUD arm Median follow-up time: 19–20 months |

Cu-IUD | DMPA and NET-EN together and separately | ITT analysis Injectables vs IUD RR 0.88 (95% CI 0.48 to 1.59) Separate ITT results for different injectables not given Per protocol analysis Injectables vs IUD RR 0.94 (95% CI 0.52 to 1.71) DMPA vs IUD RR 1.01 (95% CI 0.55 to 1.86) NET-EN vs IUD RR 0.58 (95% CI 0.14 to 2.42) |

Appropriate randomisation procedures, with good concealment of allocations at point of assignment Clearly defined comparison group |

No measurement or adjustment for condom use (or other potential confounders) No information on discontinuation or switching, or time-varying analysis of contraceptive use 19–20 month median interval for HIV testing 37% of follow-up HIV test results by self-report |

Unlikely to inform the primary question |

| Palanee-Phillips 2019,9 South Africa NIH |

Cohort; from RCT that examined effectiveness of dapivirine ring to prevent HIV; 2012–2015 | 1136 HIV-seronegative women from South African clinical study sites; 1771 person-years follow-up |

95/1136 seroconverted Median follow-up: 1.6 years HIV incidence/100 woman-years: Overall: 5.6 DMPA: 5.79 NET-EN: 6.22 Implant: 1.93 Cu-IUD: 4.48 |

Cu-IUD | DMPA NET-EN Implant |

Cu-IUD vs DMPA:adjHR 1.10 (95% CI 0.53 to 2.27)* Cu-IUD vs NET-EN: adjHR 0.98 (95% CI 0.47 to 2.04)* Cu-IUD vs implant: adjHR 2.17 (95% CI 0.59 to 7.69)* Cu-IUD vs all three hormonal methods together: adjHR 1.11 (95% CI 0.57 to 2.22)* |

Adjusted for condom use. Time-varying analysis of contraception exposure, condom use, and other relevant confounders Clearly defined comparison groups Monthly intersurvey interval |

No information on follow-up time or attrition by study group Potential for residual/ unmeasured confounding |

Informative but with important limitations |

| Evidence for Contraceptive Options and HIV Outcomes (ECHO) Trial Consortium, 2019,1

12 sites in Eswatini, Kenya, South Africa, Zambia Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, USAID and PEPFAR, Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency, South African Medical Research Council, UNFPA, Government of South Africa |

RCT, 2015–2019 | 7830 HIV-seronegative women seeking contraception (7829 randomised) | 397/7715 seroconverted HIV incidence/100 woman-years Overall: 3.81 DMPA-IM: 4.19 LNG implant: 3.31 Cu-IUD: 3.94 Follow-up time: up to 18 months |

Cu-IUD | DMPA-IM LNG-implant |

ITT analysis, Cu-IUD vs DMPA-IM: HR 0.96 (96% CI 0.75 to 1.22)* Cu-IUD vs LNG implant: HR1.18 (96% CI 0.91 to 1.53) Continuous use analysis, Cu-IUD vs DMPA-IM: adjHR 0.91 (96% CI 0.69 to 1.19)* Cu-IUD vs LNG implant: adjHR 1.18 (96% CI 0.90 to 1.55) No effect modification by age or HSV-2 status, and no substantial differences by several other factors |

Publication of full trial protocol16

Clear randomisation and allocation procedures Good adherence to allocated treatments (99% uptake; continuation 92% of follow-up time), with limited discontinuation or change of contraceptive method |

Patients and clinicians not blinded; however, study team made concerted efforts to not provide different information/counselling to women in DMPA-IM group vs other groups | Informative with few limitations |

*Estimates are for the inverse associations of those reported by the authors.

adjHR, adjusted hazard ratio; adjRR, adjusted relative risk; CI, confidence interval; Cu, copper; DMPA, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus;HSV, herpes simplex virus; IM, intramuscular; ITT, intention-to-treat;IUD, intrauterine device; LNG, levonorgestrel; NET-EN, norethisterone ethanate; OC, oral contraceptive;PEPFAR, President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief; RCT, randomised controlled trial; UNFPA, United Nations Population Fund; USAID, United States Agency for International Development; US NIH, United States National Institutes of Health; WHO, World Health Organization.

Four studies11–14 addressed our first review question, namely among women at risk of HIV (ie, women who are HIV-seronegative at baseline), does use of a Cu-IUD compared with use of another non-hormonal contraceptive method or no contraceptive method increase the risk of HIV acquisition? The only study classified as “informative but with important limitations” reported on 10-year follow-up of 1498 seronegative women recruited from a clinic for female sex workers in Mombasa, Kenya conducted between 1993 and 2003.14 A total of 15 428 follow-up visits accumulated; median number 6 (interquartile range, IQR 2–15), median interval between visits 35 (IQR 28–55) days. Thirty-one women in the study used an IUD. Overall, 248 women seroconverted, although the number in each contraceptive group was not reported. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards models compared time-varying exposure to an IUD with no contraception or tubal ligation, with adjustments including number of sexual partners each week, condom use, vaginal douching with soap products, and presence of a sexually transmitted infection or other genital infection before acquisition of HIV. The adjusted hazards ratio (adjHR) for IUD use compared with no contraception or tubal ligation was 1.1 (95% confidence interval, CI 0.4 to 3.0).

The second study followed 343 women living in Italy with an HIV-infected male partner.11 This longitudinal study conducted between 1987 and 1991 followed women enrolled in an earlier cross-sectional study that had advised women with an IUD to discontinue use because the baseline data suggested a three-fold increased risk of HIV prevalence among IUD users.16 Despite this counselling, two women continued to use an IUD; the rest of the women did not use IUDs. One of the IUD users, who did not use condoms, seroconverted during longitudinal observation.11 The very small number of exposed women, and long interval (at least 6 months) between study visits, contributed to an assessment that the study was “unlikely to inform the primary question”.

In the third longitudinal study, 1537 seronegative women attending a family planning clinic in Nairobi, Kenya were followed every 3 months between 1990 and 1992 as a pilot to test the feasibility of a larger study of contraception and HIV acquisition in women.12 Sixteen women in the entire cohort, seven of whom were IUD users, seroconverted within 12 months of study entry. The cumulative life table HIV incidence rate at 12 months per 100 IUD users at admission was 1.66 per 100 (95% CI 0.4 to 2.9) compared with 1.92 per 100 (95% CI 0.0 to 4.6) among DMPA users and 4.45 per 100 (95% CI 0.5 to 8.4) in OC users. This study was deemed “unlikely to inform the primary question”, partly because of the failure to report time-varying analyses of contraceptive exposure or relative risk estimates.

Another cohort study of women attending three family planning clinics in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania followed 1370 seronegative service users between 1992 and 1995.13 Few women were using a Cu-IUD at baseline (4.1%), compared with OCs (63.4%), DMPA (4.2%), other methods (8.0%) and no methods (20.3%). Study follow-up visits coincided with routine family planning visits, with the length of interval between visits undefined. Limited resources meant that blood for HIV testing could not be collected at every follow-up visit. Eight of the 75 women who seroconverted had ever used a Cu-IUD during follow-up, giving an adjusted relative risk (adjRR) of 0.80 (95% CI 0.38 to 1.69) compared with never-users of a Cu-IUD. There was no relationship with duration of Cu-IUD use. The adjustments included number of sexual partners but not condom use, although the authors reported that inclusion of ever-use of condom in the model did not materially change the results. The ill-defined follow-up interval, limited HIV testing, and failure to use time-varying exposure information for the risk estimates meant that this study was judged to be “unlikely to inform the primary question”.

Three studies1 9 15 addressed our second review question, namely among women at risk of HIV (ie, women who are HIV-seronegative at baseline), does use of a Cu-IUD compared with use of a specific hormonal contraceptive method increase the risk of HIV acquisition? One study was judged to be “informative with few limitations”.1 The ECHO trial was an RCT specifically designed to compare HIV incidence among women using Cu-IUDs, DMPA-IM or LNG implants; a comparison group of women not using any contraception was not included. It was conducted in 12 sites in Eswatini, Kenya, South Africa and Zambia, recruiting HIV-seronegative women aged 16–35 years and seeking contraception, with follow-up for up to 18 months. After randomisation to one of the three contraceptive methods, study visits occurred every 3 months and included HIV testing, contraceptive counselling, behavioural assessment, and HIV prevention services. Outcome assessment for HIV was conducted without knowledge of the contraception assignment, and the study worked to ensure that information and counselling provided did not differ between the study groups. Ninety-nine percent of women accepted their assigned method. Participants used their assigned method for most (92%) of the 10 409 woman-years of follow-up. More than 91% of participants attended each scheduled follow-up visit and 99% had at least one follow-up HIV test. The overall incidence of HIV was 3.81 per 100 woman-years, with no statistically significant differences observed in rates between the three contraceptive groups. The main modified intention-to–treat analysis found a HR 0.96 (96% CI 0.75 to 1.22) for the Cu-IUD compared to DMPA-IM (note that this estimate is the inverse of that reported by the authors) and HR 1.18 (96% CI 0.91 to 1.53) for Cu-IUD compared with the LNG implant. A prespecified sensitivity analysis of participants with continuous use of the contraceptive method assigned, adjusting for baseline and time-varying covariates including condom use, yielded similar results. Strengths of the ECHO trial included robust randomisation and allocation procedures, high rates of follow-up and continuation with assigned contraceptive methods, assessment of condom use and sexual behaviour as possible confounders, and appropriate intention-to-treat and prespecified sensitivity analyses. Although women and providers of services in the ECHO trial could not be blinded to contraceptive group allocation, HIV testing was conducted without knowledge of allocation, and there was no evidence that this led to the different groups of women acting, or being managed, differently with respect to important issues such as HIV prevention counselling.

A cohort study, judged to be “informative but with important limitations”, included 1136 HIV-seronegative women from South African sites originally recruited for a double-blind, placebo-controlled RCT of a monthly vaginal ring containing dapivirine for HIV-1 prevention.9 Trial participants attended monthly visits between 2012 and 2015, where standardised information about sexual behaviour and contraceptive use was collected, and pregnancy and HIV infection status were tested. Cu-IUD use comprised 15.1% of the 1771 women-years of follow-up included in the analysis, with DMPA use 50.7%, norethisterone enanthate (NET-EN) use 25.4% and implant use 8.8%. A total of 95 women seroconverted. The adjusted Cox proportional hazards model included time-varying condom use and number of sexual partners. The Cu-IUD was not associated with a significantly altered risk of HIV acquisition when compared with any of the hormonal contraceptive methods (note that these estimates are the inverse of those reported by the authors): adjHR compared with DMPA 1.10 (95% CI 0.53 to 2.27); NET-EN 0.98 (95 % CI 0.47 to 2.04); implant 2.17 (95% CI 0.59 to 7.69); all three hormonal methods together 1.11 (95% CI 0.57 to 2.22).

The third study was a pragmatic, open-label, parallel-arm RCT conducted at termination of pregnancy services within two hospitals in South Africa between 2009 and 2012.15 Participants were randomised to receive an injectable progestogen-only contraceptive (mostly DMPA, but sometimes NET-EN at the provider's discretion) or a Cu-IUD, and were followed up every 3 months. Forty-two women seroconverted, 22 of those allocated to use a Cu-IUD. The intention-to-treat analysis included 656 injectable users and 634 Cu-IUD users with a follow-up HIV test. The intention-to-treat unadjusted RR between injectable and Cu-IUD users was 0.88 (95% CI 0.48 to 1.59); per-protocol unadjusted RR 0.94 (95% CI 0.52 to 1.71). Separate per-protocol unadjusted risk estimates for the two injectables were: DMPA 1.01 (95% CI 0.55 to 1.86) and NET-EN 0.58 (95% CI 0.14 to 2.42); each compared with Cu-IUD users. The trial was considered “unlikely to inform the primary question” as it did not report on switching between groups after study entry or discontinuation rates, nor did it provide adjusted risk estimates.

IUD use versus non-hormonal contraceptive use in studies considered “informative but with important limitations” or “informative with few limitations”

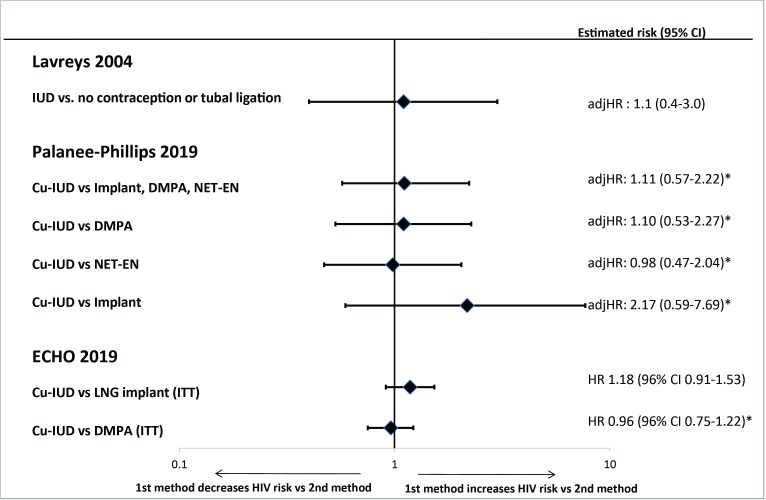

The only “informative but with important limitations” study able to examine whether IUDs are associated with an increased risk of HIV when compared with non-hormonal or no contraception did not find such an effect (figure 2).14 No studies were considered “informative with few limitations” for this question.

Figure 2.

Intrauterine device use and risk of HIV acquisition in “informative with few limitations” or “informative but with important limitations” studies. *Estimates are the inverse associations of those reported by the authors. adjHR, adjusted hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; Cu-IUD, copper intrauterine device; DMPA, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate; HR, hazard ratio; ITT, intention-to-treat; LNG, levonorgestrel; NET-EN, norethisterone enanthate

IUD use versus a specified hormonal contraceptive use in studies considered “informative but with important limitations” or “informative with few limitations”

One “informative with few limitations” study provided high-quality evidence that Cu-IUD users had a similar risk of acquiring HIV to that seen in users of DMPA-IM or the LNG implant (figure 2).1 This evidence was consistent with another “informative but with important limitations” study that found no evidence of differences in HIV risk between IUD users and users of three hormonal contraceptives, regardless of whether each hormonal method was examined separately or together.9

Discussion

This systematic search of the literature from bibliographic database inception to 26 June 2019 identified five cohort studies and two RCTs that met our inclusion criteria; one was deemed sufficiently robust to meet our “informative with few limitations” criteria,1 and two were deemed “informative but with important limitations”.9 14 None of these studies indicated an increased risk of HIV acquisition among IUD users, irrespective of whether the comparison group included non-hormonal or no contraceptive users, or users of a specific hormonal contraceptive method. None of the lower-quality “unlikely to inform the primary question” studies11–13 15 provided evidence inconsistent with the more robust studies.

Our search identified a large number of potential papers and we cross-checked the reference lists of included studies. It is unlikely, therefore, that we missed additional published data that could inform our research questions. We excluded cross-sectional studies since it is impossible to determine in such studies the time relationship between contraceptive use and HIV infection acquisition. While some studies did not specify IUD type, given the countries and years studied, the IUDs were most likely copper-bearing.

The ECHO trial was not designed to determine whether Cu-IUD use increases the risk of HIV acquisition compared with using no contraception.1 Instead, it provided direct, high-quality evidence of an absence of increased risk of acquiring HIV among Cu-IUD users, compared with women using DMPA-IM injectables or LNG implants. There was no evidence that the different contraceptive groups in the ECHO trial acted, or were managed, differently with respect to key issues such as HIV prevention counselling. Furthermore, secondary sensitivity analyses controlled for important time-varying confounders such as condomless sex. It is highly unlikely, therefore, that the ECHO trial results were affected by residual confounding (a key concern when interpreting observational studies). The high incidence of HIV in the ECHO trial, and low losses to follow-up, meant that it had sufficient statistical power to detect a 30% increase in risk of HIV between contraceptive groups assessed. Thus, it addressed another important limitation of previous observational studies, namely low power because of limited IUD usage or small number of women seroconverting.

Information from an early draft of this review, which considered only observational studies and RCTs published before the ECHO trial, was presented at a 2019 WHO Guideline Development Group meeting to assess recommendations on contraception for women at high risk of HIV. 17

Conclusion

The collective evidence from this review, which now includes information from a large high-quality RCT, does not indicate evidence of an increased risk of HIV acquisition among users of Cu-IUDs.

Additional educational resources

WHO Contraceptive Eligibility for Women at High Risk of HIV https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/contraceptive-eligibility-women-at-high-risk-of-HIV/en/

WHO Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/family_planning/Ex-Summ-MEC-5/en/

WHO Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/family_planning/SPR-3/en/

Curtis KM, Hannaford PC, Rodriguez MI, et al. Hormonal contraception and HIV acquisition among women: an updated systematic review. BMJ Sex Reprod Health 2020;46:8–16

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Joanna Taliano, MA MLS, Reference Librarian at CDC for running the search strategies.

Footnotes

Contributors: PH, AT, TC and KC contributed to the planning of this review. PH, AT, TC and KC conducted the literature search, screening, and risk of bias assessment. PH wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to subsequent drafts and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions of this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official postion of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the World Health Organization, or other institutions with which the authors are affiliated.

Competing interests: TC was a member of the ECHO trial consortium. PCH, KMC, TC participated in the 2019 WHO Guideline Development Group (GDG) process which assessed recommendations on contraception for women at high risk of HIV.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Ahmed K, Baeten JM, Beksinska M, et al. HIV incidence among women using intramuscular depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, a copper intrauterine device, or a levonorgestrel implant for contraception: a randomised, multicentre, open-label trial. Lancet 2019;394:303–13. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31288-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Achilles SL, Creinin MD, Stoner KA, et al. Changes in genital tract immune cell populations after initiation of intrauterine contraception. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014;211:489.e1–489.e9. 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.05.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sagripanti JL, Lightfoote MM. Cupric and ferric ions inactivate HIV. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 1996;12:333–6. 10.1089/aid.1996.12.333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Borkow G, Lara HH, Covington CY, et al. Deactivation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in medium by copper oxide-containing filters. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2008;52:518–25. 10.1128/AAC.00899-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Covidence Systematic Review Software Veritas health information 2019.

- 7. Curtis K, Hannaford PC, Rodriguez MI, et al. Hormonal contraception and HIV acquisition among women: an updated systematic review. BMJ Sex Reprod Health 2020;46:8–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Polis CB, Curtis KM, Hannaford PC, et al. An updated systematic review of epidemiological evidence on hormonal contraceptive methods and HIV acquisition in women. AIDS 2016;30:2665–83. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Palanee-Phillips T, Brown ER, Szydlo D, et al. Risk of HIV-1 acquisition among South African women using a variety of contraceptive methods in a prospective study. AIDS 2019;33:1619–22. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000002260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Baeten J, Palanee-Phillips T, Szydlo D, et al. Risk of HIV-1 acquisition among South African women using a variety of contraceptive methods in a prospective study (Abstract). AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2018;34:48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Saracco A, Musicco M, Nicolosi A, et al. Man-to-woman sexual transmission of HIV: longitudinal study of 343 steady partners of infected men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1993;6:497–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sinei SKA, Fortney JA, Kigondu CS, et al. Contraceptive use and HIV infection in Kenyan family planning clinic attenders. Int J STD AIDS 1996;7:65–70. 10.1258/0956462961917104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kapiga SH, Lyamuya EF, Lwihula GK, et al. The incidence of HIV infection among women using family planning methods in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. AIDS 1998;12:75–84. 10.1097/00002030-199801000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lavreys L, Baeten JM, Martin HL, et al. Hormonal contraception and risk of HIV-1 acquisition: results of a 10-year prospective study. AIDS 2004;18:695–7. 10.1097/00002030-200403050-00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hofmeyr GJ, Singata-Madliki M, Lawrie TA, et al. Effects of injectable progestogen contraception versus the copper intrauterine device on HIV acquisition: sub-study of a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care 2017;43:175–80. 10.1136/jfprhc-2016-101607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lazzarin A, Saracco A, Musicco M, et al. Man-to-woman sexual transmission of the human immunodeficiency virus. Risk factors related to sexual behavior, man's infectiousness, and woman's susceptibility. Italian Study Group on HIV Heterosexual Transmission. Arch Intern Med 1991;151:2411–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. World Health Organization Contraceptive eligibility for women at high risk of HIV. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2019. https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/contraceptive-eligibility-women-at-high-risk-of-HIV/en/ (Accessed September 13, 2019). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjsrh-2019-200512supp001.pdf (38.3KB, pdf)

bmjsrh-2019-200512supp002.pdf (59.9KB, pdf)