Graphical abstract

Keywords: Resveratrol, Diabetes, Hyperlipidemia, Metabolic parameters

Abstract

Resveratrol was recognized as the major factor responsible for the beneficial properties of red wine. Several resveratrol-based dietary supplements are available, but their efficacy has not been sufficiently tested. This study was designed to examine the effect of resveratrol supplementation, using a commercially available product, on the metabolic status of experimental animals with induced hyperlipidemia or type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Hyperlipidemia was induced by feeding the rats a standard pellet diet supplemented with cholesterol. T2DM was induced by adding 10% fructose to drinking water and streptozotocin. Treatment with resveratrol-based supplement improved glycemic control in diabetic animals and significantly decreased serum low-density-lipoprotein (LDL) and triglyceride levels, concurrently increasing the high-density-lipoprotein (HDL) levels in animals with hyperlipidemia. Resveratrol-treated animals had improved tolerance to glucose loading. Supplementation did not induce alterations in parameters of liver and renal function. Findings indicate that commercial resveratrol supplement improves metabolic control in rats with induced hyperlipidemia and T2DM.

1. Introduction

Obesity and diabetes mellitus, important independent risk factors for the development of cardiovascular disease, have reached epidemic proportions over the past decade (Bhupathiraju and Hu, 2016). Sedentary lifestyles and the consumption of diets high in saturated fats lead to excess body weight, metabolic changes and abnormal lipid profile (Margolis et al., 2014). Drugs available for the treatment of obesity, dyslipidemia and diabetes work best when used in conjunction with diet, exercise and behavior changes (Wyatt, 2013, Asaadet al., 2016). A growing body of scientific literature points out that cardiovascular risk factors in metabolic disorders can be modified through dietary interventions (Han and Lean, 2016). The Mediterranean diet, which involves high consumption of monounsaturated fatty acids, mostly from olive oil and nuts, balanced amounts of fish, fruit, vegetables and whole-grain cereals (Widmer et al., 2015), and small amounts of meat and dairy, has documented beneficial effects on obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and reduction of overall mortality (Estruch et al., 2013). An important component of the Mediterranean diet is moderate but regular consumption of red wine, which has been proven to provide health benefits for people with metabolic disorders (Pandey and Rizvi, 2014).

Beneficial effects of red wine are attributed to different phytochemicals among which, resveratrol (trans-3,5,4′-trihydroxystilbene) - a non-flavonoid phytoalexin present in grapes and berries, has attracted special attention (Wu and Hsieh, 2011, Petrovskiet al., 2011). Resveratrol was recognized as the major factor responsible for the cardioprotective properties of red wine. Resveratrol exhibits protective effects on several degenerative and cardiovascular diseases including atherosclerosis, hypertension, ischaemic diseases as well as diabetes, obesity, and aging (Petrovskiet al., 2011, Carrizzoet al., 2013, Szkudelski and Szkudelska, 2011). Many resveratrol-based supplements were developed with the idea to supplement the intake of natural antioxidants and provide the benefits associated with the consumption of red wine. However, there is limited evidence demonstrating whether resveratrol-based dietary supplements offer the same beneficial effect as red wine consumption, which contains a number of additional phytochemicals with antioxidant properties (Calabriso et al., 2016). Moreover, dietary supplements are formulated from different plant species, vary in concentrations of active ingredients, and may vary widely in their antioxidant properties (Henning et al., 2014). Manufacturers offer limited information of supplement composition, labels lack information on effective antioxidant capacity values and many supplements remain untested, poorly regulated and controlled (Ekor, 2013). Supplement efficacy depends both on the composition of the raw materials and manufacturing process as well as the stability and shelf life of the product. Even with the appropriate raw material supplied, during transportation and manufacturing there is plenty of opportunity for contamination and/or fraud to occur (LeDoux et al., 2015). Therefore, post-manufacturing testing of the content and efficacy as well as product safety assessment are important for the herbal products freely available on the market.

Consequently, this study was designed to determine resveratrol content and antioxidant activity of commercially available resveratrol-based supplement and examine the effects of supplementation on metabolic control in animals with induced diabetes and dyslipidemia.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Standards and reagents

Trans-resveratrol, gallic acid and 2,2-diphenil-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Steinheim, Germany). The solvents used were of analytical grade, ethanol Zorka Pharma (Šabac, Serbia), formic acid Lach-Ner (Neratovice, Czech Republic) and methanol HPLC grade JT Baker (Deventher, Nederlands).

Streptozotocin, cholesterol (, cholic acid, urethane, citric acid and sodium citrate dihydrate were procured from Sigma Chemicals Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA) and were stored at 2–4 °C protected from light. All other chemicals used in this study were of analytical grade purity.

2.2. Commercial dietary supplement

A commercial dietary supplement based on resveratrol for human consumption available OTC was chosen after reviewing supplements on the Serbian market. The preparation had 150 dosage units, with each unit containing 44.36 mg of dry root extract of the Japanese plant Polygonum cuspidatum standardized on a minimum 98% (m/m) of trans-resveratrol. The recommended daily dose is 4–6 units for people suffering from obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases, cancer and osteoporosis.

The dose of supplement used for rats was guided by the FDA recommended human daily dose for a male with standard weight of 70 kg (FDA, 2005). Supplement was administered as a saline suspension to experimental animals by per os gavage at a dose of 20 mg/kg of body weight daily for 7 or 30 days, according to the experimental protocol.

2.2.1. Sample preparation

Standard solutions of trans-resveratrol in pure methanol were prepared, ranging from 2.5 to 40 mg/L (R2 = 0.999). After pulverization of one dosage unit of the supplement, ultrasound assisted extraction by 80% methanol (10 mL) was applied. After 15 min of extraction, extracts were filtered through a membrane filter (0.45 µm) and analyzed for trans-resveratrol content and antioxidant activity. All measurements were performed in triplicate.

2.2.2. Quantification of trans-resveratrol in dietary supplement

For the quantification of trans-resveratrol, HPLC (High Performance Liquid Chromatography) method (Miljić et al., 2017) was employed on an Agilent 1100 Series liquid chromatograph (USA) with diode array detector, Hypersyl ODS reversed-phase C18 column and a gradient elution (A- 0.1% acetic acid in water, B- 0.1% acetic acid in acetonitrile). The column was used at 25 °C, flow rate was 1.0 mL/min, injection volume 50 µL and detection using diode array detector was at 306 nm. All injections were performed in triplicate.

2.2.3. In vitro antioxidant activity of dietary supplement

The antioxidant activity was determined spectrophotometrically by reaction with DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picryl-hydrazyl) radical (Brand-Williams et al., 1995). Appropriate growing amount of extract (50–250 µL), 1000 μL of ethanolic solution of DPPH reagent (90 µM) and ethanol to 4000 μL were added and represented sample. The control sample was prepared by adding 1000 μL of the working DPPH solution to 3000 μL of ethanol. After incubation for 1 h in the dark at room temperature, its absorbance was read on a spectrophotometer (Jenway 6405 UV/Vis, Essex, UK) at a wavelength of 515 nm, with a 95% ethanol solution as a reference. All tests were carried out in triplicate. Radical scavenging capacity (RSC) was calculated for each concentration according to the equation RSC = 100–100 × [Asample/Acontrol], where Asample represented absorbance of the analyzed samples, and Acontrol represented absorbance of the control. A calibration curve was constructed so that RSC was plotted against different concentrations of extracts, from which 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50, mg/mL) was calculated as the concentration of extract necessary for achieving 50% of RSC (Sharma and Bhat, 2009).

2.3. Animal procedures

Thirty-six, 10-week-old male white rats of the Wistar strain, weighing 250–300 g, used in the experiment were purchased from the Military-Technical Institute in Belgrade. The animals were housed in Uni-Protect (Ehret, Emmendingen, Germany) cabinets, at the Department of Pharmacology, Toxicology and Clinical Pharmacology, Faculty of Medicine, Novi Sad. The animals were maintained under controlled room temperature (23 ± 1 °C), light and dark (12:12 h) cycle. Care and experimental procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of work with laboratory animals (Approval No. 323-07-10109/2015-05).

2.3.1. Experimental protocol

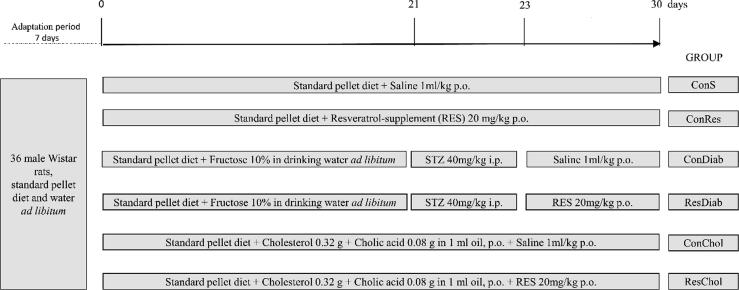

During a week of adaptation prior to the experiments animals had access to tap water and standard pellet diet ad libitum. Then, animals were randomly assigned to six (6) groups of six animals:

Group 1: Control rats treated with saline (1 mL/kg) per os for 30 days (ConS), fed standard pellet diet.

Group 2: Control rats treated with resveratrol-based dietary supplement (20 mg/kg) in aqueous solution orally for 30 days (ConRes), fed standard pellet diet.

Group 3: Diabetic rats (ConDiab). Standard pellet diet plus 10%-fructose in drinking water and 40 mg/kg b.w.-STZ.

Group 4: Diabetic rats (standard pellet diet plus 10%-fructose in drinking water and 40 mg/kg b.w.-STZ) treated with resveratrol-based dietary supplement (20 mg/kg) in aqueous solution orally for 7 days (ResDiab).

Group 5: Hyperlipidemic rats (ConChol) fed standard pellet diet with addition of cholesterol, treated with saline (1 mL/kg) per os for 30 days.

Group 6: Hyperlipidemic rats, fed standard pellet diet with addition of cholesterol, treated with resveratrol-based dietary supplement (20 mg/kg) in aqueous solution orally for 30 days (ResChol).

The treatment protocol is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Overview of the treatment protocol.

2.3.2. Induction of diabetes mellitus

Diabetes was induced through a combination of high fructose diet and streptozotocin. After the adaptation period, animals were fed a standard pellet diet and drinking water containing 10% fructose ad libitum (Wilson and Islam, 2012), for 3 weeks. Following that, streptozotocin, dissolved in citrate buffer immediately before administration, was administered in a single dose of 40 mg/kg. After 48 h, blood was taken from the tail vein for the measurement of glucose level and confirmation of diabetes. Animals with glycaemia higher than 15 mmol/L were included in further investigation. Blood from the tail vein was also taken at the beginning and at the end of experiments (Radenković et al., 2016).

2.3.3. Induction of hyperlipidemia

Hyperlipidemia was induced by feeding the animals standard pellet diet with addition of cholesterol for 30 days. Animals had access to food and water ad libitum, and received cholesterol and cholic acid, as an absorption enhancer, dissolved in olive oil via oral gavage. Each animal received near 1 mL of oil containing 0.32 g of cholesterol and 0.08 g of cholic acid daily, the exact volume being adjusted according to weekly weight measurements (Thiruchenduran et al., 2011).

2.3.4. Oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT)

On the last day of the experiment, an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) was performed on overnight fasted rats. Glucose (2 g/kg b.w.) was orally administered 30 min after pretreatment with saline (n = 6) or resveratrol supplement (n = 6). Blood was withdrawn from the tail vein at 0 (before glucose administration), 30, 60 and 120 min (after administration). Blood glucose levels were estimated using glucose oxidase-peroxidase reactive strips and a glucometer (Accu-Chek, Roche Diagnostics, USA). After the end of OGGT experiments, all animals were anesthetized with 25% aqueous solution of urethane (0.75 g/kg) intraperitoneally. After the loss of righting reflex, the animals were sacrificed by cardiopuncture and blood samples were obtained for further tests (Rašković et al., 2017). The blood samples were centrifuged for 10 min at 6000 rpm after which the supernatant was pipetted and transferred to new, properly labeled, microtubes. Until analytical processing time, samples were kept in a freezer at a temperature of −20 °C (Holen et al., 2016).

2.4. Analytical methods

The concentration of glucose was determined by commercial kits on a glucose monitoring device, Accu-chek Active (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Blood glucose was measured after 6 h fasting. The sera were used for the biochemical analyses of total cholesterol, triglycerides, LDL-cholesterol and HDL-cholesterol. Total cholesterol was determined by the CHOD-POD (cholesterol/oxidase/peroxidase) method and triglycerides by the GPO-POD (glycerol-3-phosphate/oxidase/peroxidase) method. HDL-cholesterol was determined by the CHE-CHO-POD (cholesterol/esterase/oxidase/peroxidase) method and LDL-cholesterol by the method of Friedewald et al. (1972).

In order to monitor renal function, serum urea, creatinine and uric acid were assessed, while the activities of serum aspartate transaminase (AST), serum alanine transaminase (ALT) and serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP) were measured as markers of hepatic function. These analyses were performed on the Olympus AU 400 autoanalyzer (Hamburg, Germany) by standard IFCC (International Federation of Clinical Chemistry) methods. All animals were subjected to measurement of body weight immediately before and after the end of the experiment.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS statistical software, version 19.0 (IBM SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Data were reported as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Paired two-tailed Student’s t-test was used for body weight comparison. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or Kruskal-Wallis test was employed for the comparisons between experimental groups. Post-hoc testing for ANOVA was performed using Tukey’s test. Mann-Whitney U test was used for post-hoc testing in Kruskal-Wallis analysis. All differences were considered statistically significant for a p value lower than 0.05 (p < 0.05).

3. Results

3.1. Supplement analysis on resveratrol content and antioxidant activity

Trans-resveratrol content in the dietary supplement was 44.005 ± 0.27 mg per dosage unit (Fig. 2) (99.2% of dry root extract). In vitro DPPH determination of antioxidant activity of resveratrol-based supplement confirmed the antioxidant effect of selected supplement (resveratrol-based supplement, IC50 = 0.0176 ± 0.001 mg/mL; α-tocopherol IC50 = 0.00253 mg/mL).

Fig. 2.

HPLC-DAD chromatogram of trans-resveratrol quantification in dietary supplement for calibration data: λ = 306 nm; calibration curve y = 32.2426x–0.207, x- peak area, y- concentration in mg/L; R2 = 0.999; concentration range 2.5–40 mg/L. x- retention time (min), y- absorbance at 306 nm.

3.2. Effect of the resveratrol-based supplement on the glycemic status

The effect of treatment with resveratrol based supplement on glycaemia in diabetic rats is shown in Fig. 3. A combination of 10% fructose in drinking water and streptozotocin successfully induced persistent hyperglycemia in experimental animals. There was no statistically significant difference between the groups in the blood sugar levels prior to application of streptozotocin (BSL before; p = 0.136), and 48 h after administration of streptozotocin (BSL0; p = 0.366). After seven days of treatment with resveratrol supplement, a statistically significant difference in the fasting blood glucose levels was found between treatment (ResDiab) and control (ConDiab) groups (p < 0.001). Diabetic rats treated with resveratrol had 25.46% lower blood sugar levels than the respective control. The OGTT glucose curve (Fig. 4) demonstrated that the blood glucose levels in diabetic and hyperlipidemic rats were higher than the levels in the control group as measured during 0–120 min after oral intake of glucose (Fig. 4). Resveratrol treatment significantly improved glucose tolerance in diabetic rats (p < 0.05). In addition, the OGTT showed that glucose tolerance was impaired in rats with induced hyperlipidemia, while this impairment was improved in resveratrol-treated hyperlipidemic rats.

Fig. 3.

Blood glucose levels (BGL) in rats with T2DM treated with saline (ConDiab) or dietary supplement based on resveratrol, 20 mg/kg (ResDiab). BGLbefore- prior to administration of streptozotocin, BGL0 − 48 h after the administration of streptozotocin and BGLend - on the last day of the experiment. *significantly different in comparison with ConDiab (p < 0.001).

Fig. 4.

OGTT test results of rats with T2DM and rats fed high-cholesterol diet. ConS- control group, ConRes- rats treated with dietary supplement based on resveratrol (20 mg/kg), ConDiab- rats with diabetes, ResDiab- rats with diabetes treated with dietary supplement based on resveratrol (20 mg/kg), ConChol- rats with hiperlipidemia, ResChol- rats with hyperlipidemia treated with dietary supplement based on resveratrol, 20 mg/kg.

3.3. Effect of the resveratrol-based supplement on the lipid status

Induction of hyperlipidemia was successful following a standard pellet diet with addition of cholesterol and cholic acid as an absorption enhancer. After 30 days, a statistically significant increase in total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol and triglycerides was observed (Table 1). Treatment with dietary supplement based on resveratrol significantly affected lipid metabolism in healthy, diabetic and rats with induced hyperlipidemia. Although there were no statistically significant differences in the levels of total cholesterol between the groups subjected to 30-day standard diet with addition of cholesterol who received saline (ConChol) and the resveratrol supplement (ResChol), a lower value was obtained in the group treated with dietary supplement. Importantly, a statistically significant reduction was observed between the same groups in the concentration of total triglycerides (by 40.54%, p < 0.01), and LDL-cholesterol (by 21.02%, p = 0.043), while a significant increase was noticed in HDL-cholesterol fraction (by 13.23%, p = 0.022). In rats with diabetes, there was a significant increase in total triglyceride levels (Table 1). Supplementation with resveratrol lowered total triglycerides in diabetic rats, but without statistical significance.

Table 1.

Lipid profile-plasma levels of total cholesterol, triglycerides, LDL-cholesterol and HDL-cholesterol (X ± SD).

| Group | ConS | ConRes | ConDiab | ResDiab | ConChol | ResChol | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 1.93 ± 0.22 | 1.79 ± 0.16 | 1.96 ± 0.15 | 1.74 ± 0.06 | 2.68 ± 0.16# | 2.56 ± 0.19 | <0.01 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 0.19 ± 0.04 | 0.20 ± 0.22 | 1.31 ± 0.08 | 1.20 ± 0.17 | 0.52 ± 0.10# | 0.37 ± 0.07* | <0.01/<0.01 |

| HDL (mmol/L) | 0.66 ± 0.10 | 0.62 ± 0.04 | 0.60 ± 0.07 | 0.73 ± 0.05 | 0.68 ± 0.03 | 0.77 ± 0.09* | 0.022 |

| LDL (mmol/L) | 1.18 ± 0.30 | 1.00 ± 0.15 | 1.10 ± 0.12 | 0.46 ± 0.10 | 1.90 ± 0.40# | 1.57 ± 0.12* | <0.01/0.043 |

ConS- saline 1 mL/kg p.o.; ConRes- dietary supplement based on resveratrol 20 mg/kg p.o.; ConDiab- 10% fructose-fed and streptozotocin 40 mg/kg i.p.; ResDiab- streptozotocin 40 mg/kg i.p. and dietary supplement based on resveratrol 20 mg/kg p.o. for 7 days; ConChol- hyperlipidemic control; ResChol- hyperlipidemic rats and dietary supplement based on resveratrol 20 mg/kg, p.o. for 30 days.

Statistically significant difference in comparison with ConS (p < 0.05, n = 6).

Statistically significant difference in comparison with ConChol (p < 0.05, n = 6).

3.4. Effect of the resveratrol-supplement on the body weight and biochemical parameters

In our study, there was a statistically significant increase in body weight within all experimental groups over a period of 7 and 30 days (Table 2). Rats with induced diabetes gained less weight than other animals. Comparing the results following determination of serum aminotransferase concentrations of the control and experimental groups of healthy animals (Table 3), lower values of AST (by 12.76%) and ALT (by 23.79%) were obtained in the group that was under supplementation for a period of 30 days, however, without statistical significance. For the two groups of animals with induced diabetes, lower levels of ALT, AST and ALP were noted for animals subjected to supplementation for a period of 7 days in comparison with the control group that received saline, but without statistical significance. For the two groups of animals with induced hyperlipidemia, lower values for ALT, AST and ALP were noted for animals subjected to supplementation for 30 days, but without statistical significance. Statistically significantly lower levels of ALP were measured in healthy animals (p = 0.024).

Table 2.

Initial and terminal body weight (g, X ± SD).

| Group | ConS | ConRes | ConDiab | ResDiab | ConChol | ResChol |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial body weight | 279.83 ± 12.53 | 294.00 ± 8.74 | 246.75 ± 18.07 | 220.80 ± 7.63 | 199.17 ± 17.44 | 201.00 ± 9.44 |

| Terminal body weight | 330.17 ± 13.29 | 342.50 ± 15.42 | 292.50 ± 23.66 | 258.00 ± 9.8 | 272.00 ± 12.25 | 260.40 ± 14.92 |

| Δ | 50.33 ± 9.99 | 48.50 ± 14.15 | 45.75 ± 0.74 | 37.20 ± 7.41 | 72.83 ± 20.07 | 59.40 ± 18.96 |

ConS- saline 1 mL/kg p.o.; ConRes- dietary supplement based on resveratrol 20 mg/kg p.o.; ConDiab- 10% fructose-fed and streptozotocin 40 mg/kg i.p.; ResDiab- streptozotocin 40 mg/kg i.p. and dietary supplement based on resveratrol 20 mg/kg p.o. for 7 days; ConChol- hyperlipidemic control; ResChol- hyperlipidemic rats and dietary supplement based on resveratrol 20 mg/kg, p.o. for 30 days.

Table 3.

Parameters of hepatic (AST, ALT and ALP, U/L, X ± SD) and renal (urea, mmol/L, X ± SD; creatinine and uric acid, µmol/L, X ± SD) function.

| Group | ConS | ConRes | ConDiab | ResDiab | ConChol | ResChol | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AST | 117.83 ± 11.31 | 104.50 ± 7.12 | 135.25 ± 6.06 | 122.00 ± 12.85 | 140.17 ± 35.56 | 120.40 ± 4.22 | ns |

| ALT | 29.50 ± 3.43 | 23.83 ± 2.05 | 38.00 ± 4.87 | 37.60 ± 26.60 | 30.00 ± 18.60 | 17.40 ± 1.74 | ns |

| ALP | 225.00 ± 22.86 | 163.00 ± 12.57* | 1019.25 ± 80.43 | 1005.80 ± 54.11 | 461.67 ± 42.07 | 445.21 ± 38.27 | 0.023 |

| Urea | 6.40 ± 0.86 | 5.55 ± 0.52 | 13.45 ± 3.17 | 10.64 ± 2.39 | 7.45 ± 0.72 | 7.14 ± 0.52 | ns |

| Creatinine | 60.17 ± 5.02 | 57.17 ± 5.12 | 71.50 ± 6.12 | 58.20 ± 5.98* | 55.50 ± 6.44 | 51.80 ± 1.94 | 0.024 |

| Uric acid | 88.53 ± 9.70 | 84.26 ± 11.40 | 114.25 ± 8.48 | 91.00 ± 10.62* | 114.17 ± 43.75 | 112 ± 15.50 | 0.017 |

ConS- saline 1 mL/kg p.o.; ConRes- dietary supplement based on resveratrol 20 mg/kg p.o.; ConDiab- 10% fructose-fed and streptozotocin 40 mg/kg i.p.; ResDiab- streptozotocin 40 mg/kg i.p. and dietary supplement based on resveratrol 20 mg/kg p.o. for 7 days; ConChol- hyperlipidemic control; ResChol- hyperlipidemic rats and dietary supplement based on resveratrol 20 mg/kg, p.o. for 30 days.

statistically significant difference in comparison with the respective control group (p < 0.05, n = 6). ns- non significant.

Comparing the results following determination of serum concentrations of urea, creatinine and uric acid between the control and experimental groups of animals with induced diabetes (Table 3), significantly lower levels of creatinine (by 22.85%, p = 0.024) and uric acid (by 25.55%, p = 0.017) were obtained for the group under resveratrol supplementation for a period of 7 days. A lower value was also noted for urea (by 26.41%), close to statistical significance (p = 0.057). Between the two groups of animals with induced hyperlipidemia there was no statistically significant decrease in any of the three parameters of renal function.

4. Discussion

In the present study, commercially available resveratrol dietary supplement was examined with respect to resveratrol content, antioxidant capacity, and effect on metabolic control in rats with induced experimental diabetes and dyslipidemia. Resveratrol content of the tested commercial supplement (99.2%) was in accordance with the product specification of ≈ 98% of trans-resveratrol. The DPPH free radical scavenging assay confirmed the antioxidant potential of the assayed resveratrol supplement. Radical-scavenging capacity of 1 mg of α-tocopherol, a well-known antioxidant, was found to be equivalent to 6.9 mg of the resveratrol supplement.

Resveratrol supplementation improved glycemic control in rats with diabetes induced through a combination of fructose feeding and a single dose of streptozotocin. This model serves as an alternative, non-genetic rat model for type 2 diabetes (Wilson and Islam, 2012). Improved glucose tolerance observed in the present study is in accordance with other studies which have also demonstrated that resveratrol improves insulin action in rodents with experimentally induced insulin resistance (Denget al., 2008, Bagulet al., 2012). Resveratrol can potentiate insulin action through reduced adiposity, inhibition of inflammatory gene expression and activation of SIRT1 and 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase enzymes (Szkudelski, 2001). Anti-diabetic effects of resveratrol can also be explained by high antioxidative capacity, as resveratrol was shown to be able to induce effects that may contribute to the protection of β-cells (Goyal et al., 2016). Resveratrol treatment improved glucose tolerance in an OGTT in rats with induced diabetes and hyperlipidemia. This is in accordance with the results of Yang and Kang who reported the ability of resveratrol to improve glucose load tolerance in diabetic rats (Yang and Kang, 2018). In fructose fed rats, administration of resveratrol reduced the increased blood glucose levels after an intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test (Bagul et al., 2012). Impaired tolerance to glucose load in hyperlipidemic rats is the consequence of insulin resistance. The high fat diet is known to cause insulin resistance and inflammation in visceral white adipose tissue. The mechanism that may partly explain the effect of resveratrol on insulin sensitivity is the prevention of inflammation through improvement of cellular stress and inhibition of inflammatory gene expression (Zhu et al., 2017, Chenet al., 2017, Soufiet al., 2015). Resveratrol treatment increases the expressions of pAkt, GLUT4 and IRS-1 in adipose tissues, and decreases serum proinflammatory cytokine levels (Ding et al., 2018).

Administration of cholesterol and cholic acid proved successful for induction of hyperlipidemia in Wistar rats (Thiruchenduran et al., 2011). In rats with induced hyperlipidemia, total cholesterol levels were relatively unaffected by resveratrol supplementation, but there were statistically significant differences in the levels of non-HDL and HDL fractions. Resveratrol primarily lowered the levels of LDL and triglycerides, concurrently increasing the levels of HDL. This increase in the HDL fraction is the reason for similar levels of total cholesterol in hyperlipidemic rats treated with resveratrol compared to the respective control. In diabetic rats, changes in the lipid profile presented as an increase in triglycerides, while changes in the LDL and HDL levels were not as noticeable. This confirms that the streptozotocin/fructose rat model of diabetes used here not only induces persistent hyperglycemia, but also the changes in lipid profile that are characteristic of type 2 diabetes (Mooradian, 2009). Resveratrol supplementation lowered the levels of triglycerides and increased HDL in diabetic rats, but without statistical significance. However, diabetic rats were treated for 7 days, which might explain why the changes in lipid profiles were not as pronounced as in hyperlipidemia rats which were treated for 30 days. A number of studies have confirmed that prolonged treatment with resveratrol has the ability to lower blood lipid levels in cholesterol-fed rats treated for 4 weeks (Zhu et al., 2008), hyperlipidemic mice treated for 6 weeks (Xie et al., 2014) and after 8 weeks of treatment in obese rats (Rivera et al., 2009). Similarly, 7-day resveratrol administration (50 mg/kg) failed to reduce serum cholesterol and triglyceride concentrations (Arichi et al., 1982). This might be explained by the proposed mechanism of action of resveratrol, which includes changes in the activity and expression of enzymes involved in cholesterol metabolism, which requires a certain lapse of time before the full effect is achieved. Changes in the lipid profile after resveratrol treatment are believed to be mediated through down-regulation of hepatic enzyme 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl Coenzyme A (HMG-CoA), which has a key role in the biosynthesis of cholesterol (Penumathsaet al., 2007, Doet al., 2008). Increased expression of hepatic cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase (CIP7A1) which leads to an increased synthesis and secretion of bile acids and reduction in total and LDL-cholesterol in plasma has also been suggested to be responsible for resveratrol lipid-lowering properties (Chen et al., 2012). In addition, an in vitro study showed that resveratrol can increase the expression of LDL receptors on hepatocytes and increase hepatic LDL uptake through an AMPK dependent mechanism (Yashiro et al., 2012).

Resveratrol supplementation did not significantly reduce body weight, although all three groups receiving supplementation gained less weight compared with their respective control groups that received saline. In rats with diabetes induced by a combination of high fructose diet and streptozotocin, there was less weight gain in diabetic animals in comparison with the control group, which differs from models of type 1 diabetes, where there is little endogenous insulin production, leading to hyperglycemia and weight loss (Islam and Choi, 2007). The effects of resveratrol in preventing body-weight gain in rats fed a high calorie diet are conflicting. While some authors found statistically significant body weight reductions in rodents that were fed high-fat diets supplemented with resveratrol (Kimet al., 2011, Choet al., 2012, Qiaoet al., 2014, Monteroet al., 2014, Jeonet al., 2014), certain authors observed a slight tendency towards lower body weight (Shang et al., 2008) or no changes at all (Kang et al., 2014). A recent review concluded that resveratrol effects on body fat in rodents differ depending on feeding conditions, and concluded that there is not enough evidence to propose resveratrol as a new anti-obesity treatment (Milton-Laskibar et al., 2017).

Induction of diabetes and hyperlipidemia caused changes in parameters of liver function, presenting as increased ALP but normal AST and ALT in these rats. AST and ALT are markers of hepatocyte injury and subsequent release of intracellular contents into the blood (Ozer et al., 2008). High ALP levels, with normal ALT and AST levels, indicative of cholestatic liver injury, were noted in animals with diabetes and animals with hyperlipidemia. The onset of diabetes-induced cholestasis in the rats treated with streptozotocin has been previously reported (Garcia-Mari et al., 1988), and the liver damage induced by biliary obstruction following a high fat diet is well documented (Muriel, 1995). In the animals with induced diabetes and hyperlipidemia, lower levels of ALT, AST and ALP were noted for animals subjected to resveratrol supplementation in comparison with the control group that received saline, but without statistical significance. In diabetic rats, 7 days after induction of diabetes, there was elevation of all biomarkers of renal injury. Significantly lower levels of creatinine and uric acid were obtained for diabetic rats under resveratrol supplementation in comparison with the respective control. These results are in accordance with the previous findings that resveratrol can ameliorate several types of renal injury, including diabetic nephropathy, as well as drug, sepsis and ischemia-reperfusion injury (Jianget al., 2013, Szkudelski and Szkudelska, 2015, Kitada and Koya, 2013).

5. Conclusion

The overall data obtained by the present study demonstrated antioxidant, anti-diabetic and lipid-lowering properties of a commercial resveratrol-based dietary supplement. Resveratrol supplement markedly improved the plasma lipid profile and glucose tolerance in rats with induced type 2 diabetes and hyperlipidemia. Furthermore, the good safety profile of resveratrol makes it an attractive adjunct to pharmacological management of metabolic disorders.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technological Development of the Republic of Serbia (Project No. TR31020).

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgement

We thank Gaewyn Ellison, PhD from School of Pharmacy and Biomedical Sciences, Curtin Health Innovation Research Institute, Perth, Australia, for improving the use of English in the manuscript.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The Authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

References

- Arichi H., Kimura Y., Okuda H., Baba K., Kozawa M., Arichi S. Effects of stilbene components of the roots of Polygonum cuspidatum Sieb. et Zucc. on lipid metabolism. Chem. Pharm. Bull. (Tokio) 1982;30:1766–1770. doi: 10.1248/cpb.30.1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asaad G., Soria-Contreras D.C., Bell R.C., Chan C.B. Effectiveness of a lifestyle intervention in patients with type 2 diabetes: the physical activity and nutrition for diabetes in Alberta (PANDA) trial. Healthcare (Basel) 2016;4:73. doi: 10.3390/healthcare4040073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagul P.K., Middela H., Matapally S., Padiya R., Bastia T., Madhusudana K., Reddy B.R., Chakravarty S., Banerjee S.K. Attenuation of insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome and hepatic oxidative stress by resveratrol in fructose-fed rats. Pharmacol. Res. 2012;66:260–268. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhupathiraju S.N., Hu F.B. Epidemiology of obesity and diabetes and their cardiovascular complications. Circ. Res. 2016;118:1723–1735. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand-Williams W., Cuvelier M.E., Berset C.L. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 1995;28:25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Calabriso N., Scoditti E., Massaro M., Pellegrino M., Storelli C., Ingrosso I., Giovinazzo G., Carluccio M.A. Multiple anti-inflammatory and anti-atherosclerotic properties of red wine polyphenolic extracts: differential role of hydroxycinnamic acids, flavonols and stilbenes on endothelial inflammatory gene expression. Eur. J. Nutr. 2016;55:477–489. doi: 10.1007/s00394-015-0865-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrizzo A., Puca A., Damato A., Marino M., Franco E., Pompeo F., Traficante A., Civitillo F., Santini L., Trimarco V., Vecchione C. Resveratrol improves vascular function in patients with hypertension and dyslipidemia by modulating NO metabolism. Hypertension. 2013;62:359–366. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.01009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, US Food and Drug Administration, Guidance for industry: estimating the maximum safe starting dose in initial clinical trials for therapeutics in adult healthy volunteers. Rockville MD: FDA, 2005.

- Chen L., Wang T., Chen G., Wang N., Gui L., Dai F., Fang Z., Zhang Q., Lu Y. Influence of resveratrol on endoplasmic reticulum stress and expression of adipokines in adipose tissues/adipocytes induced by high-calorie diet or palmitic acid. Endocrine. 2017;55:773–785. doi: 10.1007/s12020-016-1212-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q., Wang E., Ma L., Zhai P. Dietary resveratrol increases the expression of hepatic 7α-hydroxylase and ameliorates hypercholesterolemia in high-fat fed C57BL/6J mice. Lipids Health Dis. 2012;11:56. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-11-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho S.J., Jung U.J., Choi M.S. Differential effects of low-dose resveratrol on adiposity and hepatic steatosis in diet-induced obese mice. Br. J. Nutr. 2012;108:2166–2175. doi: 10.1017/S0007114512000347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng J.Y., Hsieh P.S., Huang J.P., Lu L.S., Hung L.M. Activation of estrogen receptor is crucial for resveratrol-stimulating muscular glucose uptake via both insulin-dependent and independent pathways. Diabetes. 2008;57:1814–1823. doi: 10.2337/db07-1750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding S., Jiang J., Wang Z., Zhang G., Yin J., Wang X., Wang S., Yu Z. Resveratrol reduces the inflammatory response in adipose tissue and improves adipose insulin signaling in high-fat diet-fed mice. PeerJ. 2018;6 doi: 10.7717/peerj.5173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do G.M., Kwon E.Y., Kim H.J., Jeon S.M., Ha T.Y., Park T., Choi M.S. Long-term effects of resveratrol supplementation on suppression of atherogenic lesion formation and cholesterol synthesis in apo E-deficient mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008;374:55–59. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.06.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekor M. The growing use of herbal medicines: issues relating to adverse reactions and challenges in monitoring safety. Front. Pharmacol. 2013;4:177. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2013.00177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estruch R., Ros E., Salas-Salvadó J., Covas M.I., Corella D., Arós F., Gómez-Gracia E., Ruiz-Gutiérrez V., Fiol M., Lapetra J., Lamuela-Raventos R.M. PREDIMED study investigators, primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a mediterranean diet. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;368:1279–1290. [Google Scholar]

- Friedewald W.T., Levy R.I., Fredrickson D.S. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin. Chem. 1972;18:499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Mari J.J., Villanueva G.R., Esteller A. Diabetes-induced cholestasis in the rat: possible role of hyperglycemia and hypoinsulinemia. Hepatology. 1988;8:332–340. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840080224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal S.N., Reddy N.M., Patil K.R., Nakhate K.T., Ojha S., Patil C.R., Agrawal Y.O. Challenges and issues with streptozotocin-induced diabetes–a clinically relevant animal model to understand the diabetes pathogenesis and evaluate therapeutics. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2016;244:49–63. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2015.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han T.S., Lean M.E. A clinical perspective of obesity, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease. JRSM Cardiovasc. Dis. 2016;5 doi: 10.1177/2048004016633371. 2048004016633371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henning S.M., Zhang Y., Rontoyanni V.G., Huang J., Lee R.P., Trang A., Nuernberger G., Heber D. Variability in the antioxidant activity of dietary supplements from pomegranate, milk thistle, green tea, grape seed, goji, and acai: effects of in vitro digestion. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014;62:4313–4321. doi: 10.1021/jf500106r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holen T., Norheim F., Gundersen T.E., Mitry P., Linseisen J., Iversen P.O., Drevon C.A. Biomarkers for nutrient intake with focus on alternative sampling techniques. Genes Nutr. 2016;11:12. doi: 10.1186/s12263-016-0527-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam M.S., Choi H. Nongenetic model of type 2 diabetes: a comparative study. Pharmacology. 2007;79:243–249. doi: 10.1159/000101989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon S.M., Lee S.A., Choi M.S. Antiobesity and vasoprotective effects of resveratrol in apoE-deficient mice. J. Med. Food. 2014;17:310–316. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2013.2885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang B., Guo L., Li B.Y., Zhen J.H., Song J., Peng T., Yang X.D., Hu Z., Gao H.Q. Resveratrol attenuates early diabetic nephropathy by down-regulating glutathione s-transferases Mu in diabetic rats. J. Med. Food. 2013;16:481–486. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2012.2686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang W., Hong H.J., Guan J., Kim D.G., Yang E.J., Koh G., Park D., Han C.H., Lee Y.J., Lee D.H. Effects of resveratrol on the insulin signaling pathway of obese mice. J. Vet. Sci. 2014;15:179–185. doi: 10.4142/jvs.2014.15.2.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S., Jin Y., Choi Y., Park T. Resveratrol exerts anti-obesity effects via mechanisms involving down-regulation of adipogenic and inflammatory processes in mice. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2011;81:1343–1351. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitada M., Koya D. Renal protective effects of resveratrol. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/568093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeDoux M.A., Appelhans K.R., Braun L.A., Dziedziczak D., Jennings S., Liu L., Osiecki H., Wyszumiala E., Griffiths J.C. A quality dietary supplement: before you start and after it’s marketed-a conference report. Eur. J. Nutr. 2015;54:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s00394-014-0827-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis, K.L., O’Connor, P.J., Morgan, T.M., Buse, J.B., Cohen, R.M., Cushman, W.C., Cutler, J.A., Evans, G.W., Gerstein, H.C., Grimm, R.H.J., Lipkin, E.W., Narayan, K.M., Riddle, M.C.J., Sood, A., Goff, D.C.J., 2014. Outcomes of combined cardiovascular risk factor management strategies in type 2 diabetes: the ACCORD randomized trial. 37, 1721-1728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Miljić U., Puškaš V., Cvejić J., Torović Lj. Phenolic compounds, chromatic characteristics and antiradical activity of plum wines. Int. J. Food Prop. 2017;20:2022–2033. [Google Scholar]

- Milton-Laskibar I., Gomez-Zorita S., Aguirre L., Fernandez-Quintela A., Gonzalez M., Portillo M. Resveratrol-induced effects on body fat differ depending on feeding conditions. Molecules. 2017;22:2091. doi: 10.3390/molecules22122091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montero M., de la Fuente S., Fonteriz R.I., Moreno A., Alvarez J. Effects of long-term feeding of the polyphenols resveratrol and kaempferol in obese mice. PLoS One. 2014;9:e112825. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooradian A.D. Dyslipidemia in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat. Clin. Pract. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009;5:150–159. doi: 10.1038/ncpendmet1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muriel P. High fat diet and liver damage induced by biliary obstruction in the rat. J. Appl. Toxicol. 1995;15:125–128. doi: 10.1002/jat.2550150211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozer J., Ratner M., Shaw M., Bailey W., Schomaker S. The current state of serum biomarkers of hepatotoxicity. Toxicology. 2008;245:194–205. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2007.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey K.B., Rizvi S.I. Role of red grape polyphenols as antidiabetic agents. Integ. Med. Res. 2014;3:119–125. doi: 10.1016/j.imr.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penumathsa S.V., Thirunavukkarasu M., Koneru S., Juhasz B., Zhan L., Pant R., Menon V.P., Otani H., Maulik N. Statin and resveratrol in combination induces cardioprotection against myocardial infarction in hypercholesterolemic rat. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2007;42:508–516. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrovski G., Gurusamy N., Das D.K. Resveratrol in cardiovascular health and disease. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2011;1215:22–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao Y., Sun J., Xia S., Tang X., Shi Y., Le G. Effects of resveratrol on gut microbiota and fat storage in a mouse model with high-fat-induced obesity. Food Funct. 2014;5:1241–1249. doi: 10.1039/c3fo60630a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radenkovic M., Stojanovic M., Prostran M. Experimental diabetes induced by alloxan and streptozotocin: The current state of the art. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods. 2016;78:13–31. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2015.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rašković A., Gigov S., Čapo I., Paut Kusturica M., Milijašević B., Kojić-Damjanov S., Martić N. Antioxidative and protective actions of apigenin in a paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity rat model. Eur. J. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2017;42:849–856. doi: 10.1007/s13318-017-0407-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera L., Moron R., Zarzuelo A., Galisteo M. Long-term resveratrol administration reduces metabolic disturbances and lowers blood pressure in obese Zucker rats. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2009;77:1053–1063. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang J., Chen L.L., Xiao F.X., Sun H., Ding H.C., Xiao H. Resveratrol improves non-alcoholic fatty liver disease by activating amp-activated protein kinase. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2008;29:698–706. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2008.00807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma O.P., Bhat T.K. DPPH antioxidant assay revisited. Food Chem. 2009;113:1202–1205. [Google Scholar]

- Soufi G.F., Arbabi-Aval E., Kanavi R.M., Ahmadieh H. Anti-inflammatory properties of resveratrol in the retinas of type 2 diabetic rats. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2015;42:63–68. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szkudelski T. The mechanism of alloxan and streptozotocin action in β cells of the rat pancreas. Physiol. Res. 2001;50:537–546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szkudelski T., Szkudelska K. Anti-diabetic effects of resveratrol. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2011;1215:34–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szkudelski T., Szkudelska K. Resveratrol and diabetes: from animal to human studies. BBA-Mol. Basis Dis. 2015;1852:1145–1154. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiruchenduran M., Vijayan N.A., Sawaminathan J.K., Devaraj S.N. Protective effect of grape seed proanthocyanidins against cholesterol cholic acid diet-induced hypercholesterolemia in rats. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2011;20:361–368. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widmer R.J., Flammer A.J., Lerman L.O., Lerman A. The Mediterranean diet, its components, and cardiovascular disease. Am. J. Med. 2015;128:229–238. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson R.D., Islam M.S. Fructose-fed streptozotocin-injected rat: an alternative model for type 2 diabetes. Pharmacol. Rep. 2012;64:129–139. doi: 10.1016/s1734-1140(12)70739-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J.M., Hsieh T. Resveratrol: a cardioprotective substance. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2011;1215:16–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt H.R. Update on treatment strategies for obesity. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013;98:1299–1306. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-3115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie H.C., Han H.P., Chen Z., He J.P. A study on the effect of resveratrol on lipid metabolism in hyperlipidemic mice. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 2014;11:209–212. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yashiro T., Nanmoku M., Shimizu M., Inoue J., Sato R. Resveratrol increases the expression and activity of the low density lipoprotein receptor in hepatocytes by the proteolytic activation of the sterol regulatory element-binding proteins. Atherosclerosis. 2012;220:369–374. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang D.K., Kang H.S. Anti-diabetic effect of cotreatment with quercetin and resveratrol in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Biomol. Ther. 2018;26:130. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2017.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L., Luo X., Jin Z. Effect of resveratrol on serum and liver lipid profile and antioxidant activity in hyperlipidemia rats. Asian Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2008;21:890. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X., Wu C., Qiu S., Yuan X., Li L. Effects of resveratrol on glucose control and insulin sensitivity in subjects with type 2 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr. Metab. 2017;14:60. doi: 10.1186/s12986-017-0217-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]