Abstract

The xenobiotic receptors pregnane X receptor (PXR) and constitutive androstane receptor (CAR) are activated by structurally diverse chemicals to regulate the expression of target genes, and they have overlapping regulation in terms of ligands and target genes. Receptor-selective agonists are, therefore, critical for studying the overlapping function of PXR and CAR. An early effort identified 6-(4-chlorophenyl)imidazo[2,1-b][1,3]thiazole-5-carbaldehyde-O-(3,4-dichlorobenzyl)oxime (CITCO) as a selective human CAR (hCAR) agonist, and this has since been widely used to distinguish the function of hCAR from that of human PXR (hPXR). The selectivity was demonstrated in a green monkey kidney cell line, CV-1, in which CITCO displayed >100-fold selectivity for hCAR over hPXR. However, whether the selectivity observed in CV-1 cells also represented CITCO activity in liver cell models was not hitherto investigated. In this study, we showed that CITCO: 1) binds directly to hPXR; 2) activates hPXR in HepG2 cells, with activation being blocked by an hPXR-specific antagonist, SPA70; 3) does not activate mouse PXR; 4) depends on tryptophan-299 to activate hPXR; 5) recruits steroid receptor coactivator 1 to hPXR; 6) activates hPXR in HepaRG cell lines even when hCAR is knocked out; and 7) activates hPXR in primary human hepatocytes. Together, these data indicate that CITCO binds directly to the hPXR ligand-binding domain to activate hPXR. As CITCO has been widely used, its confirmation as a dual agonist for hCAR and hPXR is important for appropriately interpreting existing data and designing future experiments to understand the regulation of hPXR and hCAR.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT

The results of this study demonstrate that 6-(4-chlorophenyl)imidazo[2,1-b][1,3]thiazole-5-carbaldehyde-O-(3,4-dichlorobenzyl)oxime (CITCO) is a dual agonist for human constitutive androstane receptor (hCAR) and human pregnane X receptor (hPXR). As CITCO has been widely used to activate hCAR, and hPXR and hCAR have distinct and overlapping biological functions, these results highlight the value of receptor-selective agonists and the importance of appropriately interpreting data in the context of receptor selectivity of such agonists.

Introduction

Xenobiotic receptors pregnane X receptor (PXR) and constitutive androstane receptor (CAR) transcriptionally regulate the expression of genes encoding drug-metabolizing enzymes (e.g., cytochrome P450 3A4 [CYP3A4] and CYP2B6) and transporters (Bertilsson et al., 1998; Kliewer et al., 1998; Lehmann et al., 1998; Wang et al., 2012). They heterodimerize with retinoid X receptor to bind to target gene promoters, and their transcriptional activity is induced by agonists and enhanced by coactivators, such as steroid receptor coactivator 1 (SRC-1) (Oladimeji et al., 2016). Some of the target genes can be upregulated by either receptor. For example, although CYP3A4 and CYP2B6 are the prototypical targets of human PXR (hPXR) and human CAR (hCAR), respectively, both receptors regulate these genes (Xie et al., 2000; Faucette et al., 2007; Roth et al., 2008). hPXR and hCAR induce the expression of target genes by binding to DNA response elements in the proximal promoter and distal enhancer regions of the genes (Faucette et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2012). Some chemicals activate both PXR and CAR, whereas others are specific for one receptor. Potent and selective hPXR agonists such as rifampicin (RIF) have greatly facilitated the identification of hPXR target genes (Maglich et al., 2002) Similarly, 6-(4-chlorophenyl)imidazo[2,1-b][1,3]thiazole-5-carbaldehyde-O-(3,4-dichlorobenzyl)oxime (CITCO) was identified (Maglich et al., 2003) and widely used as a selective hCAR activator that preferentially induces CYP2B6 (Auerbach et al., 2005; Faucette et al., 2006; Li et al., 2019). Together with selective hPXR agonists such as rifampicin, CITCO has been used to investigate the distinct and overlapping biologic functions of hPXR and hCAR.

In the work that identified CITCO as a selective agonist of hCAR (Maglich et al., 2003), the selectivity for hCAR versus hPXR was evaluated in a green monkey kidney cell line, CV-1, that was transiently transfected with an hCAR- and hPXR-responsive luciferase reporter gene construct (i.e., XREM-CYP3A4-LUC), together with hPXR or hCAR. CITCO displayed >100-fold selectivity for hCAR over hPXR (EC50 values for hCAR and hPXR are 25 nM and ∼3 µM, respectively). Although CITCO is highly selective for hCAR in the CV-1 assay system, it is significant that CITCO weakly activated hPXR, because CITCO has been widely used as a selective hCAR agonist to distinguish the function of hCAR from that of hPXR. However, how CITCO activates hPXR and whether CITCO activity in CV-1 cells matches that in more physiologically relevant cellular models (e.g., human liver cells) have not been investigated.

hPXR is highly expressed in the human liver to regulate drug metabolism. Physiologically relevant cellular models commonly used to study hPXR function include HepG2 cells (a human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line) and primary human hepatocytes (PHHs). Recently, HepaRG cells, which are terminally differentiated hepatic cells derived from a human hepatic progenitor cell line that retains many characteristics of PHHs, have been used as an alternative to PHHs for studying drug metabolism (Grime et al., 2010; Li et al., 2019), as PHHs are not readily available and often display considerable donor-to-donor variation. In addition, the availability of hCAR-knockout (KO) and hPXR-KO HepaRG cell lines enables investigations of hPXR- and hCAR-dependent and -independent regulation at the genetic level (Li et al., 2019). Recently, a potent and selective hPXR antagonist, SPA70 (Lin et al., 2017a,b; Chai et al., 2019), has been used to investigate hPXR-dependent biologic effects in vitro and in vivo (Li et al., 2019; Xie et al., 2019). Thus, SPA70 is a valuable pharmacologic tool for investigating the specific activation of hPXR.

In this study, we first showed that CITCO binds directly to the hPXR ligand-binding domain (LBD). As the role of CITCO in inducing CYP2B6 through hCAR has been extensively studied, we focused on the regulation of CYP3A4 by CITCO through hPXR in our cell-based assays, using HepG2, HEK293, HepaRG, and PHH cells. We showed that CITCO activates wild-type hPXR, but not hPXR with tryptophan-299 mutated to alanine (W299A) or mouse PXR (mPXR). The effect of CITCO was inhibited by SPA70, but not by hCAR knockout. Together, our data clearly indicate that CITCO binds to and activates hPXR. Our demonstration that CITCO is a dual agonist of hCAR and hPXR provides important information for interpreting previously reported data, as well as for designing future experiments to investigate the overlapping function of hCAR and hPXR.

Materials and Methods

Materials.

HepG2 (ATCC CRL-10741) human hepatocellular carcinoma and HEK293 (ATCC CRL-1573) cell lines, Eagle’s minimum essential medium (EMEM), and Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). Cell lines were authenticated by short tandem repeat DNA profiling. Penicillin-streptomycin and puromycin stock solutions, Opti-MEM Reduced Serum Medium, phenol red–free Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium, Lipofectamine 3000 Reagent, DMSO, terbium (Tb)-anti–glutathione S-transferase (GST), GST-hPXR-LBD, Tris (pH 7.5, 1 M), and dithiothreitol (1 M) were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Atlanta, GA). MgCl2 (1 M) was purchased from Boston BioProducts (Ashland, MA). Rifampicin, pregnenolone-16α-carbonitrile (PCN), and bovine serum albumin were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). CITCO was purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Minneapolis, MN). T0901317 was purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). SPA70 was synthesized by WuXi App Tec (Wuhan, China). FBS and charcoal/dextran-treated FBS were purchased from HyClone (Logan, UT). Dual-Glo luciferase assay reagent was purchased from Promega (Madison, WI). Steadylite HTS reagent and 384-well white tissue culture–treated plates were purchased from PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences (Boston, MA). All other tissue culture consumables (tissue culture flasks, disposable pipettes, and 384-well black low-volume assay plates) were purchased from Corning Incorporated (Tewksbury, MA). FAM-SRC1-B peptide was prepared by the Macromolecular Synthesis Section at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital (Lin and Chen, 2018). BODIPY FL vindoline was synthesized in house as previously reported (Lin et al., 2014). Human hepatoma HepaRG-CAR functional knockout (HepaRG CAR KO) cells (cat. no. MTOX1012-1VL), HepaRG 5F parental cells (cat. no. MTOX1010-1VL), and William’s E medium (cat. no. W1878-500ML) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. HepaRG Thaw, Plate, & General Purpose Medium Supplement (HPRG770) and serum-free induction medium (HPRG750) were purchased from GIBCO Life Technologies (Frederick, MD). PHHs were obtained through the Liver Tissue Cell Distribution System (PHH-Donor 1 = Case 19-005; PHH-Donor 2 = Case 19-007; PHH-Donor 3 = Case 19-008) (Pittsburgh, PA). Primary Hepatocyte Maintenance Supplement was purchased from GIBCO (cat. no. A15564, lot 2019822; GIBCO Life Technologies).

Time-Resolved Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer PXR Competitive Binding Assay.

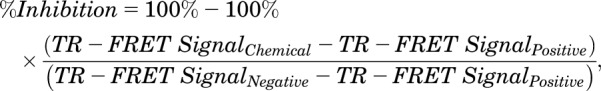

The time-resolved fluorescence resonance energy transfer (TR-FRET) PXR competitive binding assay was performed as previously described (Lin et al., 2014) with minor modifications. The PXR TR-FRET assay buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 20 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin, and 0.05 mM dithiothreitol) was used for both the TR-FRET PXR coactivator recruitment and TR-FRET PXR binding assays. Briefly, BODIPY FL vindoline (15 µl/well, 133.3 nM) was first dispensed into 384-well low-volume black assay plates. An Echo 555 Acoustic Liquid Handler (Labcyte Inc., San Jose, CA) then dispensed 60 nl/well of the indicated concentrations of tested chemicals, DMSO (as a negative control), or 3.33 mM T0901317 (as a positive control). Finally, 5 µl/well of 20 nM Tb-anti-GST and 20 nM GST-hPXR-LBD was added. The final concentrations for the assay components (in a 20-µl final assay volume per well) were as follows: BODIPY FL vindoline: 100 nM; Tb-anti-GST antibody: 5 nM; GST-hPXR-LBD: 5 nM; DMSO: 0.3%; rifampicin: from 20 µM to 9.8 nM with 1-to-2 dilutions for 12 concentration levels; CITCO: from 20 µM to 9.8 nM with 1-to-2 dilutions for 10 concentration levels; T0901317: from 10 µM to 0.17 nM with 1-to-3 dilutions for 11 concentration levels). In addition, 0.3% DMSO alone and T0901317 (10 µM, with 0.3% DMSO, diluted from 60 nl of 3.33 mM DMSO stock to a 20-µl assay volume) were also included in each plate to serve as negative and positive controls, respectively. With all assay components added, the assay plates were shaken at 900 rpm (80g) on an IKA MTS two-fourth digital microtiter plate shaker for 1 minute then briefly centrifuged at 1000 rpm (201g) for 30 seconds in an Eppendorf 5810 centrifuge equipped with an A-4-62 swing-bucket rotor (Eppendorf AG, Hamburg, Germany). The plates were then protected from light exposure and incubated for 60 minutes. After incubation, the TR-FRET signal from each well was collected with a PHERAstar FS Microplate Reader (BMG Labtech, Durham, NC). The percent inhibition for each well was calculated using eq. 1,

|

(1) |

where TR-FRET SignalChemical is the TR-FRET signal from the respective chemical-treated well, TR-FRET SignalPositive is the TR-FRET signal from the positive control well, and TR-FRET SignalNegative is the TR-FRET signal from the negative control well as indicated.

TR-FRET PXR Coactivator Recruitment Assay.

The TR-FRET PXR coactivator recruitment assay was performed as previously described (Lin and Chen, 2018) with minor modifications. Briefly, FAM-SRC1-B peptide solution (15 µl/well, 133.3 nM) was first dispensed in 384-well black low-volume assay plates. Various concentrations of tested chemicals (as stock solutions in DMSO), T0901317 (3.33 mM), or DMSO were then dispensed at 60 nl/well with the Echo 555 Acoustic Liquid Handler. Finally, 5 µl/well of 20 nM Tb-anti-GST antibody and 20 nM GST-hPXR-LBD protein were added. The final assay volume per well was 20 µl, and the final concentrations for the assay components were as follows: FAM-SRC1-B peptide: 100 nM; Tb-anti-GST antibody: 5 nM; GST-hPXR-LBD protein: 5 nM; DMSO: 0.3% in all assay wells; rifampicin and CITCO: from 20 µM to 9.8 nM with 1-to-2 dilutions for 12 concentration levels; and T0901317: 10 µM to 0.17 nM with 1-to-3 dilutions for 11 concentration levels. In addition, 0.3% DMSO alone and 10 µM T0901317 with 0.3% DMSO (diluted from 60 nl of 3.33 mM DMSO stock to 20 µl assay volume) were also included in each plate to serve as the vehicle background and reference controls, respectively. The assay plates with all assay components added were shaken at 900 rpm (80g) for 1 minute with an IKA MTS two-fourth digital microtiter plate shaker (IKA Works, Wilmington, NC), then briefly centrifuged at 1000 rpm (201g) for 30 seconds in an Eppendorf 5810 centrifuge equipped with an A-4-62 swing-bucket rotor (Eppendorf AG). The plates were then incubated for 60 minutes while protected from light exposure, and the TR-FRET signals from individual wells were collected with a PHERAstar FS Microplate Reader (BMG Labtech) after incubation. The fold-to-DMSO TR-FRET signals of each chemical at its respective concentrations were then calculated.

Cell Culture, Plasmids, and Transfection.

All cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. HEK293 cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 µg/ml streptomycin. HepG2 cells were maintained in EMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 µg/ml streptomycin. Cells were routinely verified to be mycoplasma free by using a MycoProbe Mycoplasma Detection Kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). FLAG-hPXR and CYP3A4-luciferase in pGL3 vector have been previously described (Lin et al., 2008). The CYP3A4 promoter in pGL3-CYP3A4-luciferase (Lin et al., 2008) was subcloned into pGL4.20 (Promega) to generate the pGL4.20-CYP3A4-luciferase, which was cotransfected with FLAG-hPXR into HepG2 cells. Stable cells were selected in medium containing 1 mg/ml G418 and 5 µg/ml Puromycin for 4 weeks. The HepG2 cells stably expressing FLAG-hPXR and CYP3A4-luciferase were maintained in EMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 µg/ml Puromycin, and 400 μg/ml G418. Cells were grown to 70%–80% confluence before being harvested for subcultures, transfections, or assays. Human hepatoma HepaRG-CAR functional knockout (HepaRG CAR KO) cells (cat. no. MTOX1012-1VL) and HepaRG 5F cells (HepaRG parental cells) (cat. no. MTOX1010-1VL) were grown in culture in Williams’ Medium E supplemented with HepaRG Thaw, Plate, and General Purpose Medium Supplement, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 µg/ml streptomycin for 14 days, then maintained for a further 14 days in medium containing 1.5% DMSO to differentiate the cells. Primary human hepatocytes were obtained through the Liver Tissue Cell Distribution System and were maintained in Williams’ Medium E supplemented with Primary Hepatocyte Maintenance Supplement.

Transient transfections of HEK293 cells were performed using Lipofectamine 3000 Reagent. Briefly, transfection mixture containing 625 µl of Opti-MEM Reduced Serum Medium with 5.0 µg of CYP3A4-luciferase plasmid DNA (Lin et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2013) and 0.25 µg of pRL-TK plasmid DNA (encoding Renilla luciferase as a control reporter) (Promega), with or without 0.25 µg of FLAG-hPXR wild type (WT), 0.25 µg of FLAG-hPXR-W299A (Banerjee et al., 2016), or 0.25 µg of CMV6-mPXR Kana-R (OriGene Technologies, Rockville, MD), along with 12.5 µl of P3000 reagent and 12.5 µl of Lipofectamine 3000 reagent, was mixed with 4 million HEK293 cells in 5 ml of Opti-MEM Reduced Serum Medium supplemented with 10% FBS. The transfection mixture was prepared in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. The HEK293 cell solutions mixed with the individual transfection mixtures were then transferred to T25 tissue culture flasks, and the HEK293 cells were transfected overnight before being harvested for compound treatments.

Luciferase Reporter Assays.

For the luciferase assays using transfected HEK293 cells, the transfected cells were harvested and resuspended in phenol red–free DMEM supplemented with 5% charcoal/dextran-treated FBS at 0.2 million cells/ml. The resuspended transfected HEK293 cells (25 µl/well, corresponding to 5000 cells) were dispensed into 384-well white tissue culture–treated plates. For single compound treatment, the Echo 555 Acoustic Liquid Handler was used to dispense 75 nl/well of stock dilutions of chemicals in DMSO or DMSO only (as a negative control) into the corresponding wells. The final concentrations of rifampicin, CITCO, and PCN ranged from 10 µM to 0.5 nM, with 1-to-3 dilutions for 10 concentration levels. The final DMSO concentration was 0.3% in all HEK293-based assays with single compound treatment. In cotreatments with dilutions of rifampicin and fixed concentration of CITCO, the Echo 555 Acoustic Liquid Handler dispensed 25 nl/well of stock dilutions of rifampicin in DMSO, in addition to 25 nl/well of DMSO, 1 mM CITCO, 2.5 mM CITCO, 5 mM CITCO, or 10 mM CITCO. The final concentrations of rifampicin ranged from 4.88 nM to 10 µM in a 1-to-2 dilution pattern combined with 0, 1, 2.5, 5, or 10 µM of CITCO. In cotreatments with dilutions of CITCO and fixed concentration of rifampicin, the Echo 555 Acoustic Liquid Handler dispensed 25 nl/well of stock dilutions of CITCO in DMSO, in addition to 25 nl/well of DMSO, 0.1 mM rifampicin, 0.25 mM rifampicin, 0.5 mM rifampicin, 1 mM rifampicin, or 5 mM rifampicin. The final concentrations of CITCO ranged from 4.88 nM to 10 µM in a 1-to-2 dilution pattern combined with 0, 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 1, or 5 µM of rifampicin. The final DMSO concentration was 0.2% in the rifampicin and CITCO combination study. The chemical-treated cell plates were then incubated overnight at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2, after which a Dual-Glo luciferase assay (Promega) was performed. The luminescence signals from each plate were collected with an Envision HTS Multilabel Plate Reader (Model 2102; PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences). The firefly luciferase signals were normalized to the respective Renilla luciferase signals to derive normalized luciferase signals. The relative luciferase signals for each chemical at its respective concentrations were calculated by dividing the normalized luciferase signals for the chemical by the normalized luciferase signals for the DMSO (the negative control).

For the luciferase assays with the HepG2 hPXR-CYP3A4-luciferase stable cells, a protocol was adopted that was similar to that for the HEK293 cells, except that a slightly different drug-treatment regimen was used. In the single-compound test, the Echo 555 Acoustic Liquid Handler dispensed 75 nl/well of stock dilutions of chemicals in DMSO or DMSO only into 384-well white tissue culture–treated plates, along with an additional 25 nl/well DMSO (to serve as a vehicle control when compared with treatments with two compounds). The final concentrations of rifampicin, CITCO, and SPA70 ranged from 20 µM to 0.61 nM with 1-to-2 dilutions for 16 concentration levels. In the two-compound combination test (using dilutions of rifampicin or CITCO, along with various fixed concentrations of SPA70), the Echo 555 Acoustic Liquid Handler dispensed 75 nl/well of stock dilutions of rifampicin or CITCO in DMSO or DMSO only into 384-well white tissue culture–treated plates, along with an additional 25 nl/well of SPA70 DMSO stock (10, 2, 1 mM, 500, or 100 µM) or DMSO alone. The final rifampicin and CITCO concentrations ranged from 20 µM to 9.8 nM with 1-to-2 dilutions for 12 concentration levels (in the presence of 10, 2, 1 µM, 500, 100, or 0 nM SPA70 as indicated). The final DMSO concentration was 0.4% (negative control) in all HepG2 hPXR-CYP3A4-luciferase stable cell-based assays. The chemical-treated cell plates were then incubated overnight at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2, after which the luciferase was assayed using the Steadylite HTS reagent. The luminescence signals for each plate were collected using the Envision HTS Multilabel Plate Reader. The relative luciferase signals for each chemical at its respective concentrations were calculated by dividing the firefly luciferase signals from the compound by that from the DMSO control and expressed as relative luciferase unit.

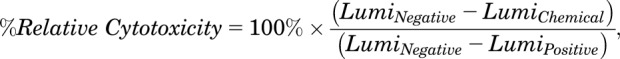

Cytotoxicity Assays.

In the HEK293 and HepG2 hPXR-CYP3A4-luciferase stable cell–based cytotoxicity assays, assay plates were prepared identically to those for the luciferase reporter assays. In addition, designated wells without cells but with other assay components present were included in each assay plate. After an overnight incubation, the chemical-treated plates were subjected to cytotoxicity assays using the CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay reagent (Promega). The luminescence signals for each plate were collected using the Envision HTS Multilabel Plate Reader. The DMSO wells with cells served as negative controls, and the DMSO wells without cells served as positive controls. The percent relative cytotoxicity for each well was calculated using eq. 2,

|

(2) |

where LumiNegative is the luminescence signal from the negative control group, LumiChemical is the luminescence signal from the respective chemical-treated well, and LumiPositive is the luminescence signal from the positive control group.

Dose-Response Data Analysis.

In the luciferase reporter, cytotoxicity, TR-FRET PXR competitive binding, and TR-FRET PXR coactivator recruitment assays, chemicals were tested in quadruplicate at least three times. For the dose-response data analysis, the relative luciferase signals in the luciferase assays, the relative cytotoxicity in the cytotoxic assays, the percent inhibition in the PXR TR-FRET competitive binding assays, and the fold-to-DMSO TR-FRET signal in the PXR TR-FRET coactivator recruitment assays of each chemical at the corresponding concentrations were plotted using GraphPad PRISM software (version 8.1.1; GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) to derive the dose-response curve and corresponding IC50 or EC50 values, if applicable, via the built-in sigmoidal dose-response fitting equation.

Computational Docking Studies.

In silico docking of CITCO to hPXR was performed using the GLIDE module (Halgren et al., 2004) from Schrodinger version 11.6. The structure of CITCO was prepared using the Ligprep module, where the structure was converted from two-dimensional to three-dimensional format, hydrogen atoms were added, and possible ionization states at pH 7 were generated (Sastry et al., 2013). The crystal structure of hPXR LBD (Lin et al., 2017b) was obtained from the Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics Protein Data Bank (code 5X0R). Chain B was processed using the Protein Preparation Wizard in the Maestro suite from Schrodinger to remove water molecules and include correct hetero atom bond order and protonation state (Kumar et al., 2018). Molecular docking experiments were executed using the Ligand Docking protocol (SP-mode) in the Maestro suit from Schrodinger with the grid set to encompass the ligand binding site of hPXR LBD, and the poses were ranked based on scores provided by GLIDE (Tahlan et al., 2019).

RNA Isolation and Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction Analysis.

Primary human hepatocytes were seeded in collagen I–coated six-well plates. Upon receipt from provider, Williams’ Medium E supplemented with Primary Hepatocyte Maintenance Supplement was used to replace the shipping medium, and the PHHs were grown for 24 hours, after which they were induced with the respective compounds dissolved in DMSO for an additional 72 hours in fresh Williams’ Medium E supplemented with Primary Hepatocyte Maintenance Supplement. Differentiated HepaRG cells were seeded in 24-well plates at 0.4 × 106 cells/well and maintained in Williams’ Medium E supplemented with HepaRG Thaw, Plate, and General Purpose Medium Supplement (HPRG770; Invitrogen) for 3 days. The cells were then treated with the respective chemicals for 24 hours in Williams’ Medium E supplemented with serum-free induction medium (HPRG750; Invitrogen). Final DMSO concentration was 0.1% (for both PHHs and HepaRG cells). Total RNA was isolated from the cells by using Maxwell 16 LEV SimplyRNA Tissue Kits (Promega). In each case, cDNA was generated from 2 µg of RNA by using a SuperScript VILO cDNA Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen). Five microliters of diluted cDNA (1:10) was used to perform quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) in an ABI 7900HT system (Applied Biosystems), using TaqMan gene expression assays specific for CYP3A4 (Hs00604506_m1), with RNA18S (Hs03928990_g1) being used as reference genes (Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Fold induction values were calculated according to the following equation: fold change = 2−ΔΔCt, where ΔCt represents the differences in cycle threshold numbers between the target gene and reference gene and ΔΔCt represents the relative change in these differences between the control and treatment groups.

Mammalian Two-Hybrid Assay.

For these assays, the CheckMate Mammalian Two-Hybrid System (Promega) was used. The pG5-luc, pACT-hPXR, and pBIND–SRC-1 plasmids have been described previously (Wang et al., 2013). pACT contains the herpes simplex virus protein 16 activation domain (VP16-AD). pBIND contains the Gal4 DNA binding domain therefore pBIND-SRC-1 is also referred to as Gal4-SRC-1. For this study, pACT-hPXR LBD (also referred to as VP16-hPXR) containing residues 139–434 of hPXR LBD was generated with the Q5 Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (New England Biolabs) using primers 5′-GGAGTGCAGGGGCTGACAGAGGAGCAGCGGATGATGATC-3′ and 5′-GTGTCGACGGATCCCTGGCGATCC-3′ and the previously described pACT-hPXR as template. For each assay, 1 µg of the pG5-luc and 0.5 µg each of the pACT-hPXR LBD and pBIND-SRC-1 vector constructs (a 2:1:1 ratio) was transfected into HepG2 cells in six-well plates. The respective empty vector constructs were used as controls. The pG5-luc construct contains five Gal4 binding motifs and expresses firefly luciferase, whereas the pBIND–SRC-1 vector expresses Renilla luciferase as an internal transfection control. Twenty-four hours after transfection, the cells were transferred into 96-well plates and treated with 0.1% DMSO, 5 µM rifampicin, or CITCO (1 or 10 µM) for an additional 24 hours. A Dual-Glo Luciferase Assay Kit (Promega) was used to measure both the firefly luciferase activity and the Renilla luciferase activity. The relative luciferase activity was obtained by normalizing the firefly luciferase activity to the Renilla luciferase activity.

Western Blot Analysis.

HepaRG cells and PHHs were treated with the respective chemical compounds for 72 hours in six-well plates, with the compound or medium being replaced each day. Cells were rinsed with cold PBS and harvested using a cell scraper in radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, and 0.1% SDS) with 1× protease inhibitors. Then, for each sample, 40 µg of protein (lysate) was loaded onto NuPAGE 4%–12% Bis-Tris Protein Gels (Invitrogen) and electrophoretically separated using 1× NuPAGE MES running buffer. The proteins were then transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane by using an iBlot Gel Transfer Device (Invitrogen). The membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk for 1 hour, then probed with mouse monoclonal antibodies against CYP3A4 (K03) (Schuetz et al., 1996) or β-actin (A5441; Sigma). This step was followed by incubation with a secondary goat anti-mouse antibody (IR-dye 800CW; LI-COR Biosciences), and protein bands were visualized with an Odyssey infrared imager (LI-COR Biosciences).

Statistical Analysis.

Results are expressed as the means ± S.D. of at least three independent experiments. Significance was established when P < 0.05. Student’s t test was used for comparisons of the means of two groups as specified. All qRT-PCR graphs were generated using Graphpad PRISM version 8. For qRT-PCR, analysis and experimental significance was established using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test for all samples compared with the DMSO control. For the mammalian two-hybrid assay, samples were analyzed using two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparisons test.

Results

CITCO Binds Directly to hPXR.

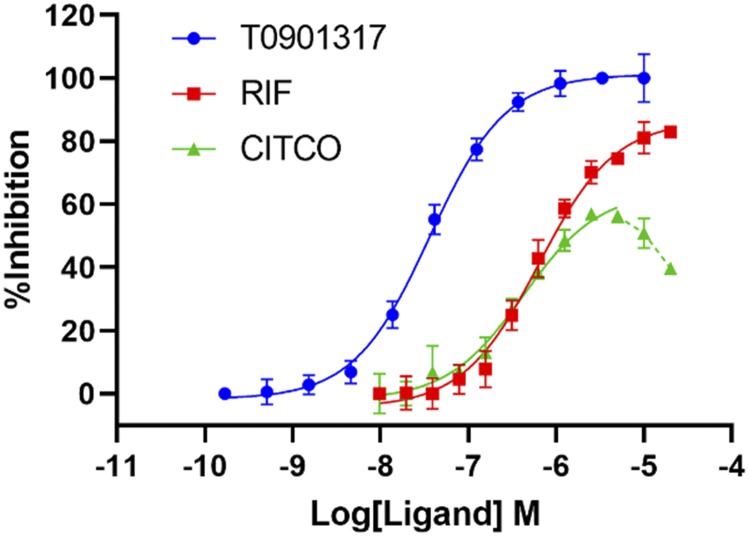

To determine whether CITCO bound directly to the hPXR LBD, we used an in vitro TR-FRET competition ligand-binding assay that employed an hPXR-binding probe, BODIPY FL vindoline (Lin et al., 2014). T0901317, a potent hPXR agonist, was used as a positive control. T0901317 inhibited the binding of BODIPY FL vindoline to hPXR in a dose-responsive manner, with an IC50 value of 36.4 nM (Fig. 1). At a concentration of 10 µM, T0901317 completely inhibits the binding of BODIPY FL vindoline to hPXR (100% inhibition) (Lin et al., 2014). DMSO was used as a vehicle negative control (0% inhibition). As shown in Fig. 1, CITCO binds to the hPXR LBD and inhibits the binding of BODIPY FL vindoline to hPXR in a dose-dependent manner with an IC50 value of 1.55 µM. At a concentration of 5 µM, CITCO displayed a maximal inhibitory activity of 56.2%. The inhibitory activity at the higher concentrations tested (10 and 20 µM) decreased, possibly because of its poor solubility in the assay system (represented by the dotted line of the CITCO dose response curve in Fig. 1; the inhibitory activities of CITCO at these two high concentrations were not included to derive its IC50 value). The IC50 value for rifampicin is 0.94 µM. These data indicate that, similar to rifampicin, CITCO binds directly to the hPXR LBD.

Fig. 1.

CITCO binds directly to hPXR. Dose-response curves for T0901317, RIF, and CITCO in the hPXR TR-FRET binding assay are shown. Results are expressed as the means ± S.D. of three independent experiments performed in quadruplicate. “%Inhibition” is determined as described in Materials and Methods and represents the binding activity of the compound.

CITCO Activates hPXR but Not mPXR.

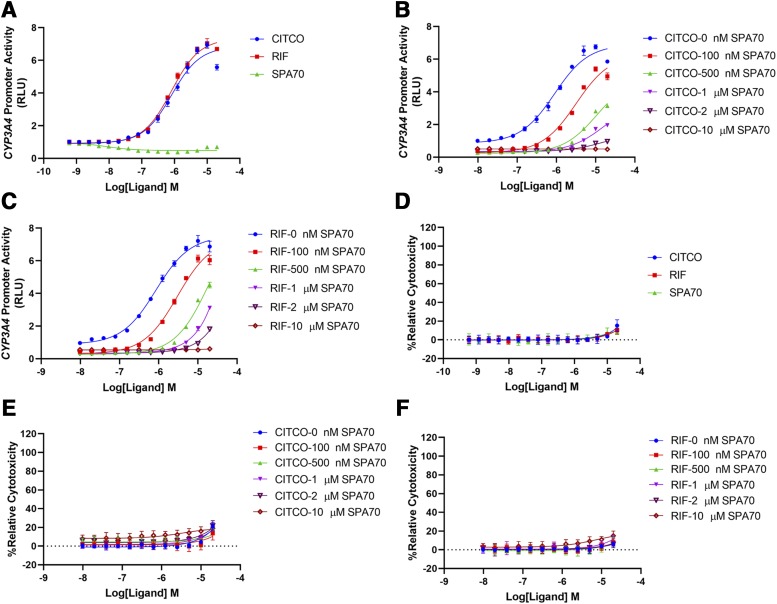

To determine whether CITCO induced hPXR-mediated CYP3A4 promoter activation, we used HepG2 cells stably expressing FLAG-hPXR and an hPXR-regulated CYP3A4 promoter luciferase reporter (CYP3A4-luciferase) (Lin et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2013). As shown in Fig. 2A, CITCO activated the CYP3A4 promoter with an EC50 of 0.82 µM and the maximal activation represented a 6.94-fold increase over that of the DMSO control at a concentration of 10 µM. As a reference, rifampicin had an EC50 of 0.81 µM and the maximal activation represented a 7.04-fold increase over that of the DMSO control (at a concentration of 10 µM). The activity of CITCO was blocked by a specific hPXR antagonist, SPA70 (Lin et al., 2017b), in a dose-responsive manner (Fig. 2B), indicating that the effect of CITCO on the CYP3A4 promoter is hPXR dependent. Consistent with a previous report (Lin et al., 2017b), SPA70 also inhibited rifampicin in a dose-responsive manner (Fig. 2C). At a concentration of 10 µM, SPA70 completely inhibited all concentrations of both rifampicin and CITCO. These three compounds exhibited very low toxicity in corresponding cytotoxicity assays (Fig. 2, D–F), confirming that the antagonistic effect of SPA70 on rifampicin and CITCO is not due to its cytotoxicity.

Fig. 2.

CITCO activates hPXR in HepG2 cells stably expressing FLAG-hPXR-WT and CYP3A4-luciferase. (A) Dose-response curves for CITCO, RIF, and SPA70. (B) Dose-response curves for CITCO in the presence of 0, 100, 500 nM, 1, 2, or 10 µM SPA70. (C) Dose-response curves for rifampicin (RIF) in the presence of 0, 100, 500 nM, 1, 2, or 10 µM SPA70. (D–F) Cytotoxicity assays corresponding to (A–C), respectively. The activity of the hPXR-regulated CYP3A4-luciferase is used to measure the activation of hPXR and is expressed as “CYP3A4 Promoter Activity,” in relative luciferase unit (RLU) as described in Materials and Methods. “%Relative Cytotoxicity” is calculated as described in Materials and Methods. Results are expressed as the means ± S.D. of three independent experiments performed in quadruplicate.

HepG2 cells have low levels of endogenous hPXR and hCAR (Yokobori et al., 2019), and both hPXR and hCAR regulate CYP3A4 promoter activity. To further confirm the hPXR-activating effect of CITCO, we used the human embryonic kidney cell line HEK293, which does not express endogenous hPXR or hCAR. In HEK293 cells transiently transfected with CYP3A4-luciferase and pRL-TK (encoding Renilla luciferase as a transfection control), with ectopic expression of hPXR-WT (Fig. 3A), but not of a vector control (Fig. 3B), CITCO induced hPXR-mediated CYP3A4 promoter activation, further confirming the agonistic effect of CITCO on hPXR. As expected, in the hPXR assay, the mPXR-specific agonist PCN did not activate hPXR (Fig. 3A) (PCN is, thus, a negative control for hPXR). In HEK293 cells transiently transfected with hPXR, CITCO activated hPXR to a lesser extent when compared with rifampicin (Fig. 3A), which is consistent with the observation noted in the original report that identified CITCO as a selective hCAR agonist that CITCO only weakly activated hPXR when compared with rifampicin in green monkey kidney CV-1 cells. Therefore, CITCO is a weaker hPXR agonist than rifampicin in HEK293 cells transiently transfected with hPXR. However, in HepG2 cells stably expressing hPXR, the EC50 of CITCO is comparable to that of rifampicin (Fig. 2A). The differential potency of CITCO in HepG2 and HEK293 cells likely reflects the contribution of cellular context to the action of ligands. Using the HEK293 cell model, we also investigated the effect of cotreatment with CITCO and rifampicin on hPXR activation (Supplemental Fig. 1). CITCO showed an additive effect with low concentrations of rifampicin but had no effect on high concentrations of rifampicin. These results are consistent with the observations that while both CITCO and rifampicin are agonists of hPXR, CITCO is weaker than rifampicin in HEK293 cells.

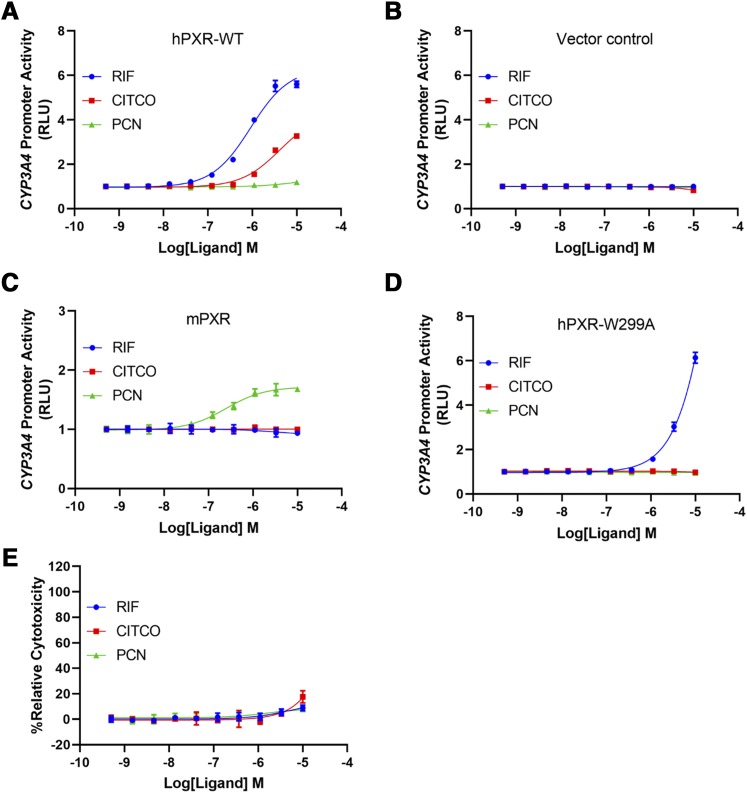

Fig. 3.

CITCO activates hPXR-WT, but not hPXR-W299A or mPXR, in HEK293 cells. (A) Dose-response curves for RIF, CITCO, and PCN in HEK293 cells transiently transfected with FLAG-hPXR-WT, CYP3A4-luciferase, and pRL-TK (Renilla luciferase transfection control). (B) Dose-response curves for RIF, CITCO, and PCN in HEK293 cells transiently transfected with CYP3A4-luciferase and pRL-TK (without FLAG-hPXR-WT). (C) Dose-response curves for RIF, CITCO, and PCN in HEK293 cells transiently transfected with CMV6-mPXR, CYP3A4-luciferase, and pRL-TK. (D) Dose-response curves for RIF, CITCO, and PCN in HEK293 cells transiently transfected with FLAG-hPXR-W299A, CYP3A4-luciferase, and pRL-TK. (E) Cytotoxicity of RIF, CITCO, and PCN in HEK293 cells. Results are expressed as the means ± S.D. of three independent experiments performed in quadruplicate. RLU, relative luciferase unit.

As shown in Fig. 3C, CITCO did not activate mPXR, indicating that the agonistic effect of CITCO is specific for hPXR. As assay controls, hPXR-specific rifampicin (used as a negative control) did not activate mPXR, but PCN (used as a positive control) did so. PCN activates mPXR with an EC50 value of 0.25 µM, which is consistent with previously reported results (Nallani et al., 2003). As shown in Fig. 3E, the compounds tested have very low cytotoxicity in HEK293 cells. Together, these data indicate that CITCO is an agonist for hPXR but not for mPXR.

The Agonistic Effect of CITCO Depends on Tryptophan-299 of hPXR.

Recently, an indirect hCAR activator, phenobarbital, was shown to activate hPXR in a manner that depends on a single aromatic amino acid, tryptophan-299 (Li et al., 2019). Interestingly, mutating tryptophan-299 to alanine (hPXR-W299A) abolished the agonistic effect of CITCO on hPXR (Fig. 3D), indicating that CITCO also depends on tryptophan-299 to activate hPXR. Consistent with previous reports, the W299A mutant also decreased the response to rifampicin (Banerjee et al., 2016; Li et al., 2019).

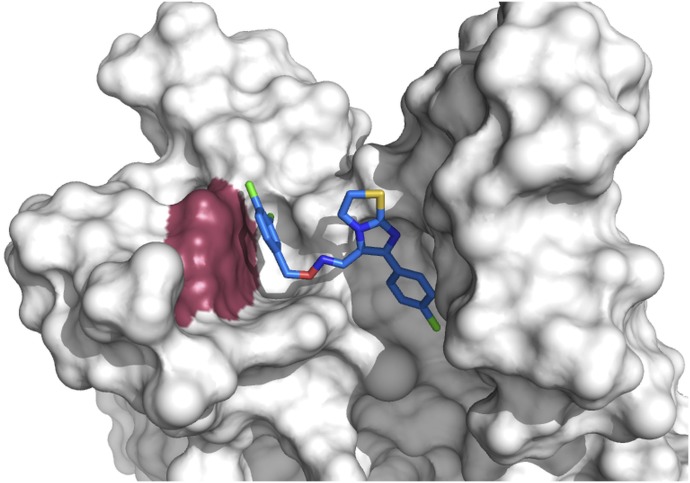

To understand the structural basis of CITCO-mediated hPXR activation and its dependency on tryptophan-299, we docked the structure of CITCO to the ligand binding pocket of hPXR LBD (Fig. 4). The preferred computational docking pose suggests that CITCO interacts with multiple residues of hPXR with mostly hydrophobic character. Notably, the 3,4-dichlorobenzyl ring moiety of CITCO shows a strong π-π interaction with the W299 residue, which could explain the reduction of agonistic activity of hPXR-W299A by CITCO.

Fig. 4.

Computational docking analysis indicates that CITCO interacts with W299 of hPXR-WT through π–π interactions. CITCO (stick representation with carbon atoms in blue) residing in the ligand binding pocket of hPXR-WT (white) displaying π–π interactions with W299 (raspberry red). The ligand binding pocket of hPXR is partially displayed as white surface for clarity. The color scheme for the ligand represented as sticks: red, oxygen; yellow, sulfur; purple, nitrogen; green, chlorine.

CITCO Induces Recruitment of SRC-1 to hPXR.

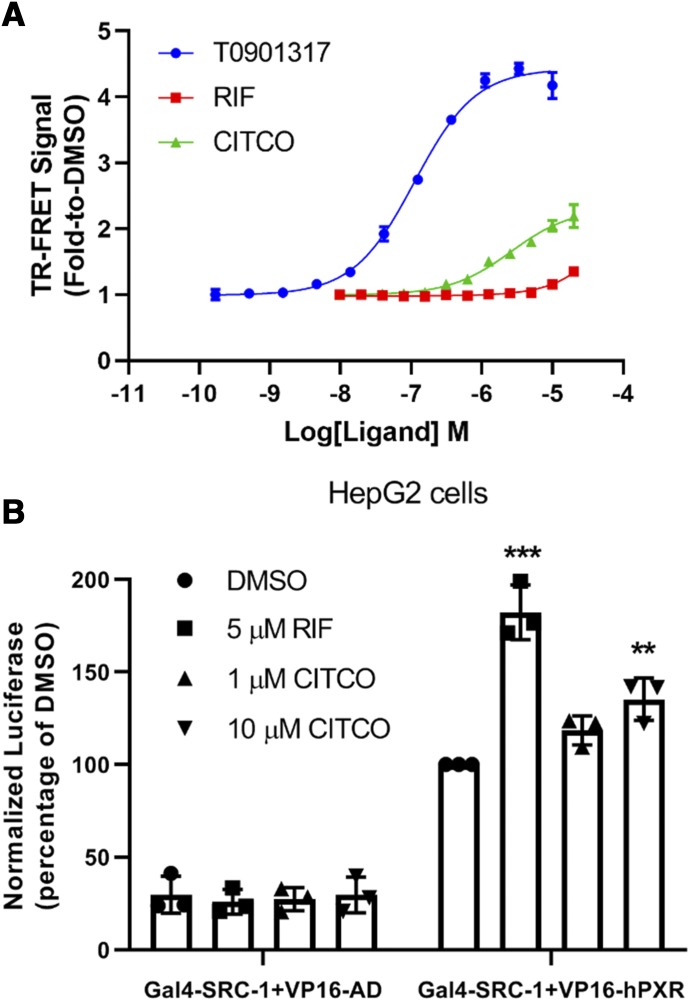

An agonist of hPXR would be expected to bind to hPXR and recruit coactivators such as SRC-1. To investigate whether CITCO exhibited this property, we first employed an in vitro hPXR TR-FRET coactivator recruitment assay in which a fluorescently labeled SRC-1 peptide (FAM-SRC1-B) was used as previously reported (Lin and Chen, 2018). As shown in Fig. 5A, CITCO and two known hPXR agonists, T0901317 and rifampicin, recruited SRC-1 peptide to hPXR in a dose-responsive manner. T0901317 is the most potent hPXR agonist and was used as a positive control. Consistent with our previous report (Lin and Chen, 2018), the EC50 value of T0901317 was 110.9 nM, with the maximal TR-FRET signal (shown as the fold increase over that of the DMSO vehicle control) being 4.43-fold at 3.33 µM and 4.18-fold at 10 µM. The maximal TR-FRET signals for CITCO and rifampicin were 2.20-fold at 20 µM and 1.35-fold at 20 µM, respectively (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

CITCO enhances the recruitment of coactivator SRC-1 to hPXR. (A) Dose-response curves for T0901317, RIF, and CITCO in the hPXR TR-FRET coactivator recruitment assay. The TR-FRET signal (fold-to-DMSO), as described in Materials and Methods, is used to represent hPXR–SRC-1 interaction. Results are expressed as the means ± S.D. of three independent experiments performed in quadruplicate. (B) Mammalian two-hybrid assay in HepG2 cells. “Normalized luciferase (percentage of DMSO)” represents the interaction of hPXR with SRC-1 and is calculated by normalizing firefly luciferase activity to Renilla luciferase activity. Data are shown as the means ± S.D. (n = 3) (**P < 0.005; ***P < 0.001). The asterisks indicate significant difference between ligand treated (RIF and CITCO) compared with DMSO control samples (Gal4-SRC-1 + VP16-hPXR). VP16-AD, pACT which contains the herpes simplex virus protein 16 (VP16) activation domain (AD).

We further examined the CITCO-induced hPXR recruitment of SRC-1 in cells by using the mammalian two-hybrid assay, using rifampicin as a positive control. As shown in Fig. 5B, in the absence of hPXR (Gal4-SRC-1 and VP16-AD vector control), neither rifampicin nor CITCO enhanced the basal (DMSO) luciferase reporter signal. In the presence of hPXR LBD (Gal4-SRC-1 and VP16-hPXR), the basal luciferase reporter signal (DMSO) increased, reflecting the basal interaction level between hPXR and SRC-1. As expected, the interaction was increased by rifampicin (5 µM). CITCO also enhanced the hPXR/SRC-1 interaction in a dose-responsive manner (at 1 and 10 µM). Together with data shown in Figs. 1–4, these data indicate that CITCO binds to the hPXR LBD to activate hPXR by recruiting the coactivator SRC-1.

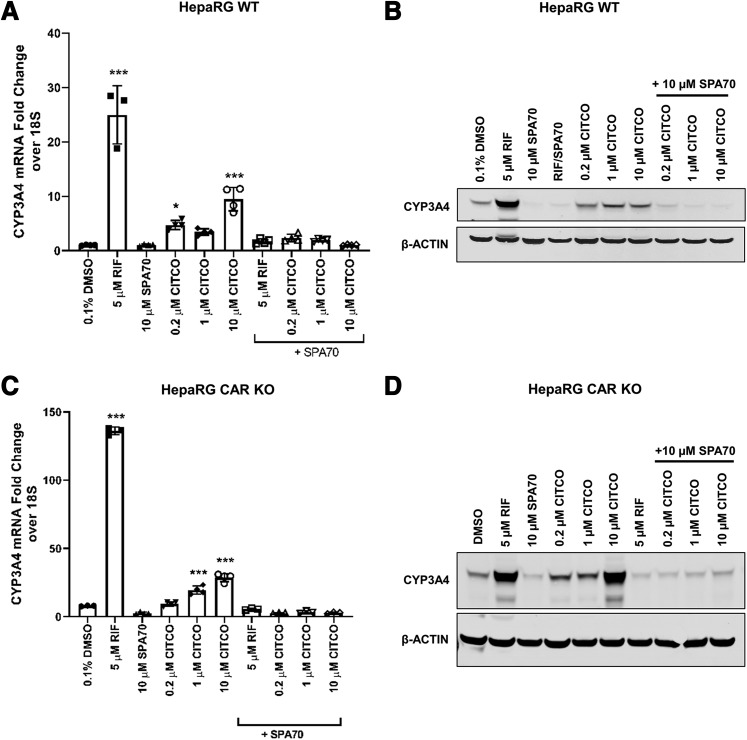

CITCO Induces CYP3A4 Expression in HepaRG Cell Models Independent of hCAR.

To confirm our observations made in HepG2 and HEK293 cells that CITCO activates hPXR, we took advantage of HepaRG cell models (using parental and hCAR knockout cells). HepaRG cells are hepatic cells derived from a human hepatic progenitor cell line, and they retain many features of PHHs, including the endogenous expression of hPXR and hCAR as well as CYPs (e.g., CYP3A4 and CYP2B6). As expected, 5 µM rifampicin robustly induced the expression of CYP3A4 at both the mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 6, A and B). CITCO at all concentration tested (0.2, 1, and 10 µM) also increased both the mRNA and protein levels of CYP3A4 (Fig. 6, A and B). SPA70 is an hPXR-specific antagonist that does not inhibit hCAR (Lin et al., 2017b). The inducing effect of both rifampicin and CITCO on CYP3A4 was almost abolished by SPA70. This is consistent with the fact that rifampicin is an hPXR-specific agonist and SPA70 an hPXR-specific antagonist and indicates that, like rifampicin, CITCO depends on hPXR to induce CYP3A4.

Fig. 6.

CITCO induces CYP3A4 expression in HepaRG cells in an hPXR-dependent but hCAR-independent manner. Differentiated parental (WT) and CAR KO HepaRG cells were treated with 5 µM RIF; 10 µM SPA70; 0.2, 1, or 10 µM CITCO; or combinations as indicated for 24 or 72 hours for mRNA and protein analysis, respectively. Cell homogenates from WT and CAR KO cells were analyzed for CYP3A4 mRNA levels (A and C). The corresponding protein expression levels for WT (B) and CAR KO (D) cells are shown. β-Actin was used as a protein loading control. For qRT-PCR analysis, data are shown as the means ± S.D. (n = 3) (*P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001).

To further confirm that CITCO induces CYP3A4 primarily through hPXR and not through hCAR, we used differentiated HepaRG cells in which hCAR had been knocked out (HepaRG CAR KO cells). In the absence of hCAR, CITCO, as well as rifampicin, could still enhance CYP3A4 mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 6, C and D). Furthermore, both rifampicin- and CITCO-induced CYP3A4 expression were abolished by SPA70 (Fig. 6, D and E). The observations that SPA70, but not knockout of hCAR in HepaRG cells, abolished the inducing effect of CITCO on CYP3A4 induction clearly indicate that CITCO is an agonist of hPXR and that it induces the expression of CYP3A4 primarily through hPXR.

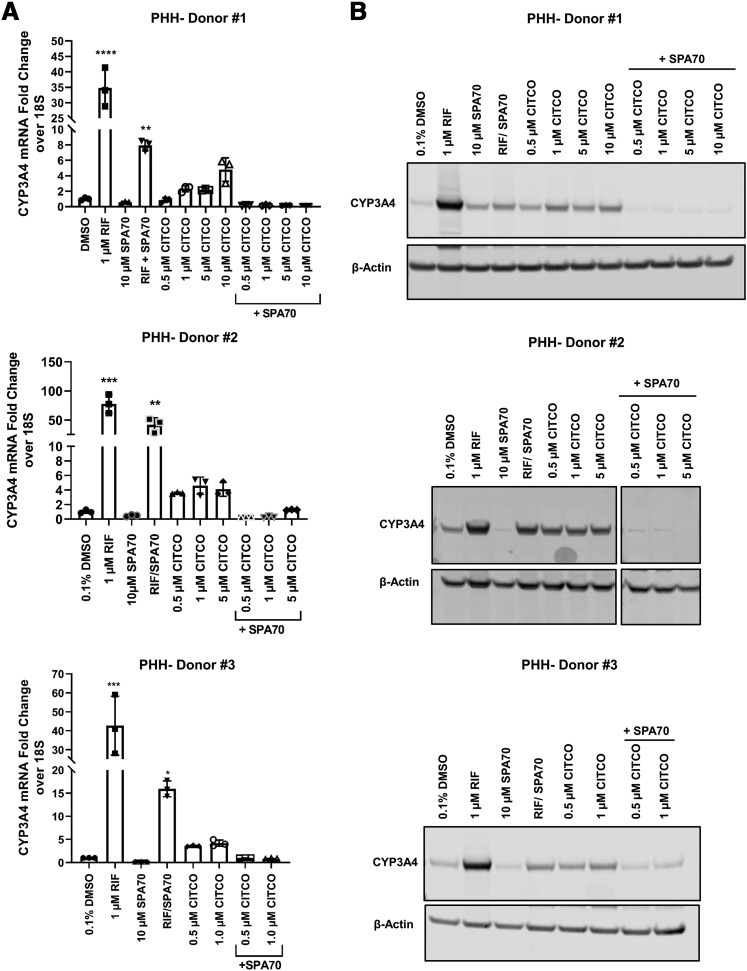

CITCO Induces CYP3A4 Expression in Primary Human Hepatocytes in an hPXR-Dependent Manner.

We further evaluated the agonistic effect of CITCO on hPXR by using PHHs (from three different donors). PHH is the gold-standard model for evaluating xenobiotics and xenobiotic receptor–mediated expression of drug-metabolizing enzymes. Consistent with our observations in HepG2 and HepaRG cells, CITCO induced CYP3A4 mRNA and protein levels to varying extents that reflected the expected donor-to-donor variation (Fig. 7); however, the inductive effect of CITCO on CYP3A4 was consistently inhibited by SPA70. Rifampicin was used as a control; it induced CYP3A4 mRNA robustly, but its inducing effect was attenuated by SPA70. Taken together, these data suggest that CITCO induces CYP3A4 by activating hPXR.

Fig. 7.

CITCO induces CYP3A4 expression in PHHs in an hPXR-dependent manner. PHHs (Donors 1–3) were treated with DMSO control; 1 µM RIF; 10 µM SPA70; 0.5, 1, 5, or 10 µM CITCO; or combinations as indicated for 72 hours for mRNA (A) and protein (B) analysis. β-Actin was used as a protein loading control. For qRT-PCR analysis, data are shown as the means ± S.D. (n = 3) (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.005; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001).

Discussion

PXR and CAR are the master xenobiotic receptors with overlapping regulation in terms of the ligands that activate them (such as rifampicin and CITCO) and the target genes (such as CYP2B6 and CYP3A4) they regulate (Chai et al., 2016, 2019). Some chemicals activate both PXR and CAR, whereas others are specific for one receptor. For example, the antimalarial artemisinin and the antipsychotic chlorpromazine activate both hPXR and hCAR (Burk et al., 2005; Faucette et al., 2007), whereas the antibiotic rifampicin and the synthetic small molecule SR12813 selectively activate hPXR (Bertilsson et al., 1998; Blumberg et al., 1998; Lehmann et al., 1998; Jones et al., 2000). Our understanding of the specific regulation of PXR and CAR in cell models in which both PXR and CAR are endogenously expressed has been facilitated by experimental genetic downregulation (as in knockdown or knockout studies) (Cheng et al., 2011) and by the development of small modulators that specifically regulate each receptor (Chai et al., 2016). Alternatively, non–physiologically relevant cell models lacking endogenous expression of PXR or CAR (such as HEK293 and CV-1 cells) have been used to study each receptor individually by expressing it ectopically (Maglich et al., 2003). When using small molecule modulators to study receptor-specific regulation in cell models endogenously expressing both PXR and CAR, the selectivity of the small molecule modulators is crucial for the study outcomes to be meaningful.

Because CITCO was identified as a selective hCAR agonist (Maglich et al., 2003), it has been widely used to investigate the selective regulation of hPXR and hCAR (Li et al., 2019), although it was known that CITCO activates hPXR in CV-1 cells with an EC50 of ∼3 µM. However, whether and how CITCO activates hPXR in more physiologically relevant models, such as liver cell models, has hitherto been unknown. In our study, we have provided the first evidence to show that CITCO directly binds to hPXR. Enabled by the recent development of the specific hPXR antagonist SPA70, we showed that in three liver cell models (HepG2, HepaRG, and PHH cells), CITCO induces CYP3A4 expression in an hPXR-dependent manner. By using HepaRG cells with CAR KO, we clearly showed that CITCO induces CYP3A4 independently of hCAR. hPXR and mPXR have very different ligand profiles, and as expected, CITCO does not activate mPXR. Recently, W299 of hPXR has been shown to control the agonistic efficacy of many hPXR ligands (Banerjee et al., 2016; Li et al., 2019). Consistent with the important role of W299 in regulating ligand efficacy, we showed that the agonistic effect of CITCO also requires W299. Even though the importance of W299 in PXR’s transcriptional activity could be correlated to its significant intermolecular interactions with the aromatic group of CITCO, more studies are needed to investigate whether the W299A mutation reduces the binding of CITCO to hPXR or decreases activation efficacy (e.g., reducing activation function-2 [AF-2] helix stabilization in the agonistic mode). These studies were hampered by the inability to obtain purified hPXR-LBD-W299A due to protein instability. We also showed that CITCO recruits the co-activator SRC-1 to hPXR in both in vitro and mammalian two-hybrid assays. Thus, our study comprehensively establishes CITCO as an agonist of hPXR that interacts directly with the hPXR LBD, involves W299, and recruits SRC-1 to carry out its agonistic function. Therefore, CITCO is a dual agonist of hCAR and hPXR.

There are two commonly used hCAR agonists: CITCO and phenobarbital. CITCO directly binds and activates hCAR, whereas phenobarbital activates hCAR through an indirect signaling mechanism that involves the inhibition of epidermal growth factor receptor signaling (Mutoh et al., 2013). Interestingly, it was recently reported that phenobarbital is also a dual activator of hCAR and hPXR (Li et al., 2019). It is also interesting that most CAR inhibitors (inverse agonists), such as PK11195, clotrimazole, meclizine, and androstanol, also function as hPXR activators (Cherian et al., 2015). Although we still lack clear structural and mechanistic insights into why and how hPXR binds most, if not all modulators (inhibitors and activators) of CAR and translates the binding of these CAR modulators (regardless whether they activate or inhibit CAR) into cellular activation of hPXR, it appears that hPXR is more promiscuous than CAR in terms of ligand binding, leading to cellular activation of the receptor and the induction of downstream transcriptional targets. Of the two master xenobiotic receptors, hPXR appears to be a more promiscuous (and, thus, more important) xenobiotic receptor than CAR.

It has also become necessary to carefully reevaluate the relation between hCAR and hPXR (in terms of both regulation and cellular function). How do they co-regulate target genes? Are they redundant and do they compensate each other? At what levels do they cross-talk (at the ligand binding, target promoter binding, or cofactor-binding levels)? We noticed that in HepaRG CAR knockout cells, the CYP3A4-inducing activity of both rifampicin (most apparently at the mRNA level) and CITCO (at both the mRNA and protein levels) increased when compared with that in parental HepaRG WT cells (Fig. 6). The possibility that these observations indicate a previously unrecognized inhibitory effect of hCAR on hPXR, albeit one that is mechanistically unclear, warrants further investigations into the relation between PXR and CAR. To facilitate such investigations, there is an urgent need to develop hCAR-specific modulators (inhibitors or activators).

In summary, we have clearly shown that CITCO, previously known to be and used as an hCAR-selective agonist, is actually a dual agonist of hPXR and hCAR. As both hPXR and hCAR are now known to play important physiologic and pathologic roles in energy metabolism, inflammation, and cell proliferation, in addition to their roles in drug metabolism (Oladimeji and Chen, 2018), appropriately dissecting the function of hPXR and hCAR with suitable genetic or chemical tools, developed using appropriate cell models, becomes more important for defining the distinct physiologic and pathologic roles of each of these receptors.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Macromolecular Synthesis Section at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital for preparing the FAM-SRC1-B peptide, other members of the Chen research laboratory for valuable discussions, and Dr. Keith A. Laycock of the St. Jude Department of Scientific Editing for editing the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- AD

activation domain

- CAR

constitutive androstane receptor

- CITCO

6-(4-chlorophenyl)imidazo [2,1-b][1,3]thiazole-5-carbaldehyde-O-(3,4-dichlorobenzyl)oxime

- CYP2B6

cytochrome P450 2B6

- CYP3A4

cytochrome P450 3A4

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

- EMEM

Eagle’s minimum essential medium

- GST

glutathione S-transferase

- hCAR

human CAR

- hPXR

human PXR

- KO

knockout

- LBD

ligand-binding domain

- mPXR

mouse PXR

- PCN

pregnenolone-16α-carbonitrile

- PHH

primary human hepatocyte

- PXR

pregnane X receptor

- qRT-PCR

quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

- RIF

rifampicin

- SRC-1

steroid receptor coactivator 1

- Tb

Terbium

- TR-FRET

time-resolved fluorescence resonance energy transfer

- VP16

herpes simplex virus protein 16

- W299A

tryptophan-299 mutated to alanine

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Lin, Bwayi, Wu, Li, Chen.

Conducted experiments: Lin, Bwayi, Wu, Li, Huber.

Performed data analysis: Lin, Bwayi, Wu, Li, Chai.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Lin, Bwayi, Wu, Li, Chai, Huber, Chen.

Footnotes

This work was supported by ALSAC, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, and the National Institutes of Health [Grants R35GM118041 (to T.C.), P30-CA21765 (to the St. Jude Cancer Center)]. Primary human hepatocytes were obtained through the Liver Tissue and Cell Distribution System (Pittsburgh, PA), which was funded by NIH (contract HHSN276201200017C). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

This article has supplemental material available at molpharm.aspetjournals.org.

This article has supplemental material available at molpharm.aspetjournals.org.

References

- Auerbach SS, Stoner MA, Su S, Omiecinski CJ. (2005) Retinoid X receptor-alpha-dependent transactivation by a naturally occurring structural variant of human constitutive androstane receptor (NR1I3). Mol Pharmacol 68:1239–1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee M, Chai SC, Wu J, Robbins D, Chen T. (2016) Tryptophan 299 is a conserved residue of human pregnane X receptor critical for the functional consequence of ligand binding. Biochem Pharmacol 104:131–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertilsson G, Heidrich J, Svensson K, Asman M, Jendeberg L, Sydow-Bäckman M, Ohlsson R, Postlind H, Blomquist P, Berkenstam A. (1998) Identification of a human nuclear receptor defines a new signaling pathway for CYP3A induction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:12208–12213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumberg B, Sabbagh W, Jr, Juguilon H, Bolado J, Jr, van Meter CM, Ong ES, Evans RM. (1998) SXR, a novel steroid and xenobiotic-sensing nuclear receptor. Genes Dev 12:3195–3205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burk O, Arnold KA, Nussler AK, Schaeffeler E, Efimova E, Avery BA, Avery MA, Fromm MF, Eichelbaum M. (2005) Antimalarial artemisinin drugs induce cytochrome P450 and MDR1 expression by activation of xenosensors pregnane X receptor and constitutive androstane receptor. Mol Pharmacol 67:1954–1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai SC, Cherian MT, Wang YM, Chen T. (2016) Small-molecule modulators of PXR and CAR. Biochim Biophys Acta 1859:1141–1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai SC, Lin W, Li Y, Chen T. (2019) Drug discovery technologies to identify and characterize modulators of the pregnane X receptor and the constitutive androstane receptor. Drug Discov Today 24:906–915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng J, Ma X, Gonzalez FJ. (2011) Pregnane X receptor- and CYP3A4-humanized mouse models and their applications. Br J Pharmacol 163:461–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherian MT, Lin W, Wu J, Chen T. (2015) CINPA1 is an inhibitor of constitutive androstane receptor that does not activate pregnane X receptor. Mol Pharmacol 87:878–889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faucette SR, Sueyoshi T, Smith CM, Negishi M, Lecluyse EL, Wang H. (2006) Differential regulation of hepatic CYP2B6 and CYP3A4 genes by constitutive androstane receptor but not pregnane X receptor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 317:1200–1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faucette SR, Zhang TC, Moore R, Sueyoshi T, Omiecinski CJ, LeCluyse EL, Negishi M, Wang H. (2007) Relative activation of human pregnane X receptor versus constitutive androstane receptor defines distinct classes of CYP2B6 and CYP3A4 inducers. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 320:72–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grime K, Ferguson DD, Riley RJ. (2010) The use of HepaRG and human hepatocyte data in predicting CYP induction drug-drug interactions via static equation and dynamic mechanistic modelling approaches. Curr Drug Metab 11:870–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halgren TA, Murphy RB, Friesner RA, Beard HS, Frye LL, Pollard WT, Banks JL. (2004) Glide: a new approach for rapid, accurate docking and scoring. 2. Enrichment factors in database screening. J Med Chem 47:1750–1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SA, Moore LB, Shenk JL, Wisely GB, Hamilton GA, McKee DD, Tomkinson NC, LeCluyse EL, Lambert MH, Willson TM, et al. (2000) The pregnane X receptor: a promiscuous xenobiotic receptor that has diverged during evolution. Mol Endocrinol 14:27–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliewer SA, Moore JT, Wade L, Staudinger JL, Watson MA, Jones SA, McKee DD, Oliver BB, Willson TM, Zetterström RH, et al. (1998) An orphan nuclear receptor activated by pregnanes defines a novel steroid signaling pathway. Cell 92:73–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Singh J, Narasimhan B, Shah SAA, Lim SM, Ramasamy K, Mani V. (2018) Reverse pharmacophore mapping and molecular docking studies for discovery of GTPase HRas as promising drug target for bis-pyrimidine derivatives. Chem Cent J 12:106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann JM, McKee DD, Watson MA, Willson TM, Moore JT, Kliewer SA. (1998) The human orphan nuclear receptor PXR is activated by compounds that regulate CYP3A4 gene expression and cause drug interactions. J Clin Invest 102:1016–1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Welch MA, Li Z, Mackowiak B, Heyward S, Swaan PW, Wang H. (2019) Mechanistic insights of phenobarbital-mediated activation of human but not mouse pregnane X receptor. Mol Pharmacol 96:345–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin W, Chen T. (2018) Using TR-FRET to investigate protein-protein interactions: a case study of PXR-coregulator interaction. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol 110:31–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin W, Goktug AN, Wu J, Currier DG, Chen T. (2017a) High-throughput screening identifies 1,4,5-substituted 1,2,3-triazole analogs as potent and specific antagonists of pregnane X receptor. Assay Drug Dev Technol 15:383–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin W, Liu J, Jeffries C, Yang L, Lu Y, Lee RE, Chen T. (2014) Development of BODIPY FL vindoline as a novel and high-affinity pregnane X receptor fluorescent probe. Bioconjug Chem 25:1664–1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin W, Wang YM, Chai SC, Lv L, Zheng J, Wu J, Zhang Q, Wang YD, Griffin PR, Chen T. (2017b) SPA70 is a potent antagonist of human pregnane X receptor. Nat Commun 8:741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin W, Wu J, Dong H, Bouck D, Zeng FY, Chen T. (2008) Cyclin-dependent kinase 2 negatively regulates human pregnane X receptor-mediated CYP3A4 gene expression in HepG2 liver carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem 283:30650–30657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maglich JM, Parks DJ, Moore LB, Collins JL, Goodwin B, Billin AN, Stoltz CA, Kliewer SA, Lambert MH, Willson TM, et al. (2003) Identification of a novel human constitutive androstane receptor (CAR) agonist and its use in the identification of CAR target genes. J Biol Chem 278:17277–17283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maglich JM, Stoltz CM, Goodwin B, Hawkins-Brown D, Moore JT, Kliewer SA. (2002) Nuclear pregnane x receptor and constitutive androstane receptor regulate overlapping but distinct sets of genes involved in xenobiotic detoxification. Mol Pharmacol 62:638–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutoh S, Sobhany M, Moore R, Perera L, Pedersen L, Sueyoshi T, Negishi M. (2013) Phenobarbital indirectly activates the constitutive active androstane receptor (CAR) by inhibition of epidermal growth factor receptor signaling. Sci Signal 6:ra31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nallani SC, Goodwin B, Maglich JM, Buckley DJ, Buckley AR, Desai PB. (2003) Induction of cytochrome P450 3A by paclitaxel in mice: pivotal role of the nuclear xenobiotic receptor, pregnane X receptor. Drug Metab Dispos 31:681–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oladimeji P, Cui H, Zhang C, Chen T. (2016) Regulation of PXR and CAR by protein-protein interaction and signaling crosstalk. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 12:997–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oladimeji PO, Chen T. (2018) PXR: more than just a master xenobiotic receptor. Mol Pharmacol 93:119–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth A, Looser R, Kaufmann M, Blättler SM, Rencurel F, Huang W, Moore DD, Meyer UA. (2008) Regulatory cross-talk between drug metabolism and lipid homeostasis: constitutive androstane receptor and pregnane X receptor increase Insig-1 expression. Mol Pharmacol 73:1282–1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sastry GM, Adzhigirey M, Day T, Annabhimoju R, Sherman W. (2013) Protein and ligand preparation: parameters, protocols, and influence on virtual screening enrichments. J Comput Aided Mol Des 27:221–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuetz EG, Schinkel AH, Relling MV, Schuetz JD. (1996) P-glycoprotein: a major determinant of rifampicin-inducible expression of cytochrome P4503A in mice and humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93:4001–4005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahlan S, Kumar S, Ramasamy K, Lim SM, Shah SAA, Mani V, Narasimhan B. (2019) In-silico molecular design of heterocyclic benzimidazole scaffolds as prospective anticancer agents. BMC Chem 13:90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YM, Lin W, Chai SC, Wu J, Ong SS, Schuetz EG, Chen T. (2013) Piperine activates human pregnane X receptor to induce the expression of cytochrome P450 3A4 and multidrug resistance protein 1. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 272:96–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YM, Ong SS, Chai SC, Chen T. (2012) Role of CAR and PXR in xenobiotic sensing and metabolism. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 8:803–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie W, Barwick JL, Simon CM, Pierce AM, Safe S, Blumberg B, Guzelian PS, Evans RM. (2000) Reciprocal activation of xenobiotic response genes by nuclear receptors SXR/PXR and CAR. Genes Dev 14:3014–3023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y, Xu M, Deng M, Li Z, Wang P, Ren S, Guo Y, Ma X, Fan J, Billiar TR, et al. (2019) Activation of pregnane X receptor sensitizes mice to hemorrhagic shock-induced liver injury. Hepatology 70:995–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokobori K, Azuma I, Chiba K, Akita H, Furihata T, Kobayashi K. (2019) Indirect activation of constitutive androstane receptor in three-dimensionally cultured HepG2 cells. Biochem Pharmacol 168:26–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]