Abstract

Damage to respiratory neural circuitry and consequent loss of diaphragm function is a major cause of morbidity and mortality after cervical spinal cord injury (SCI). Upon SCI, inspiratory signals originating in the medullary rostral ventral respiratory group (rVRG) become disrupted from their phrenic motor neuron (PhMN) targets, resulting in diaphragm paralysis. Limited growth of both damaged and spared axon populations occurs after central nervous system trauma attributed, in part, to expression of various growth inhibitory molecules, some that act through direct interaction with the protein tyrosine phosphatase sigma (PTPσ) receptor located on axons. In the rat model of C2 hemisection SCI, we aimed to block PTPσ signaling to investigate potential mechanisms of axon plasticity and respiratory recovery using a small molecule peptide mimetic that inhibits PTPσ. The peptide was soaked into a biocompatible gelfoam and placed directly over the injury site immediately after hemisection and replaced with a freshly soaked piece 1 week post-SCI. At 8 weeks post-hemisection, PTPσ peptide significantly improved ipsilateral hemidiaphragm function, as assessed in vivo with electromyography recordings. PTPσ peptide did not promote regeneration of axotomized rVRG fibers originating in ipsilateral medulla, as assessed by tracing after adeno-associated virus serotype 2/mCherry injection into the rVRG. Conversely, PTPσ peptide stimulated robust sprouting of contralateral-originating rVRG fibers and serotonergic axons within the PhMN pool ipsilateral to hemisection. Further, relesion through the hemisection did not compromise diaphragm recovery, suggesting that PTPσ peptide-induced restoration of function was attributed to plasticity of spared axon pathways descending in contralateral spinal cord. These data demonstrate that inhibition of PTPσ signaling can promote significant recovery of diaphragm function after SCI by stimulating plasticity of critical axon populations spared by the injury and consequently enhancing descending excitatory input to PhMNs.

Keywords: breathing, functional recovery, regeneration, respiratory, SCI

Introduction

Functional recovery after spinal cord injury (SCI) remains a clinical challenge attributable significantly, in part, to an inability to restore damaged neural circuits. A critical factor limiting axon growth in the adult central nervous system (CNS) is the expression of various inhibitory molecules within the lesion site and surrounding spinal cord, including Nogo,1 myelin-associated glycoprotein,2,3 oligodendrocyte myelin glycoprotein,4 and chondroitin sulfate proteogylcans (CSPGs). The leukocyte common antigen-related phosphatase (LAR) family of receptors that includes LAR, protein tyrosine phosphatase σ (PTPσ), and PTPδ plays an important role in mediating axon growth inhibition through direct binding to surface inhibitory molecules present in the injured spinal cord. LAR family receptors, concentrated on the axon membrane, bind to inhibitory molecules leading to growth cone stalling mediated significantly by the RhoA pathway.5 Inhibiting these interactions has been shown to enhance forms of axon plasticity such as regeneration and sprouting. For example, digestion of CSPG GAG side chains with chondroitinase ABC results in increased axon growth in models of CNS trauma.6–8 Moreover, blocking these interactions with small molecule inhibitors to LAR and PTPσ can enhance regeneration and sprouting of spared fibers, resulting in some functional recovery after SCI.9–11 The aim of our study was to explore mechanisms of respiratory neural circuit plasticity and diaphragm functional recovery after cervical SCI mediated by the interruption of PTPσ signaling. We tested the effect of a PTPσ peptide inhibitor on respiratory neuronal plasticity and functional restoration using a rat model of C2 hemisection SCI. After mid-to-high cervical SCI, rostral ventral respiratory group (rVRG) neurons located in the medulla become axotomized and their synaptic connections to phrenic motor neurons (PhMNs) in the C3–C5 spinal cord becomes disrupted, resulting in diaphragm paralysis. We applied a PTPσ inhibitory peptide after C2 hemisection locally to the injury site and surrounding spinal cord using a gelfoam release strategy, starting treatment immediately after SCI and then adding a piece of gelfoam freshly soaked with peptide at 1 week post-injury. We labeled both injured ipsilateral-originating and spared contralateral-originating rVRG axons using an adeno-associated virus 2 (AAV2)-mCherry vector to specifically trace rVRG axon regeneration and sprouting mechanisms after treatment. Further, we tested the effect of the PTPσ peptide on hemidiaphragm functional recovery.

Methods

Experimental design

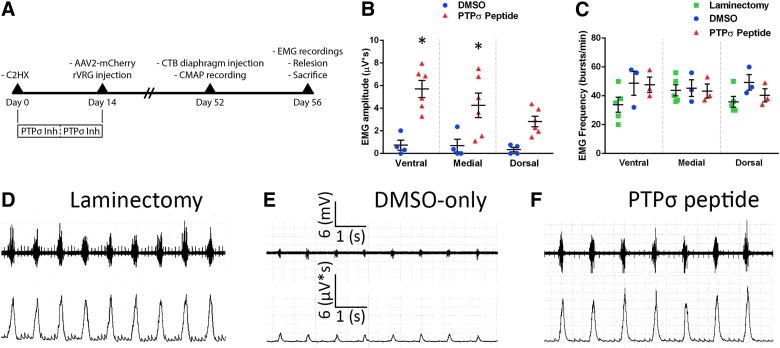

After C2 hemisection SCI in rats, we placed over the lesion a gelfoam saturated with either the PTPσ peptide or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)-only control. At 1 week post-injury, we added a freshly soaked piece of gelfoam to extend peptide delivery. At 4 days before sacrifice, we performed compound muscle action potential (CMAP) recordings to assess functional diaphragm innervation by PhMNs. At 8 weeks after injury, we conducted electromyography (EMG) recordings at three subregions of the hemidiaphragm (ventral, medial, and dorsal) to assess effects on inspiratory diaphragm activation in vivo during eupnic breathing; we then immediately performed a relesion through the hemisection site and recorded EMG activity again after the relesion. The experimental timeline is described in Figure 1A.

FIG. 1.

PTPσ inhibition improved diaphragm function after cervical SCI. Timeline of experimental design (A). Quantification of integrated EMG amplitudes 8 weeks after C2 hemisection showed a significant increase in the PTPσ peptide group at medial and ventral subregions (B). DMSO-only (ventral, 0.735 ± 0.446 μV*s, n = 4; medial, 0.685 ± 0.565, n = 4; dorsal, 0.346 ± 0.202, n = 4). PTPσ peptide (ventral, 5.702 ± 0.753 μV*s, n = 6; medial, 4.253 ± 1.082, n = 6; dorsal, 2.823 ± 0.467, n = 6). p values for DMSO-only versus PTPσ peptide (ventral, p = 0.0003; medial, p = 0.008; dorsal, p = 0.084). EMG recordings also show no differences in burst frequency across groups at all hemidiaphragm subregions (C). Laminectomy (ventral, 33.8 ± 5.16 [bursts/min], n = 5; medial, 43.8 ± 3.93, n = 5; dorsal, 35.8 ± 3.72, n = 5); DMSO (ventral, 48.7 ± 8.35 [bursts/min], n = 3; medial, 45.3 ± 5.81, n = 3; dorsal, 49.3 ± 5.46, n = 3); and PTPσ peptide (ventral, 47.7 ± 5.36 [bursts/min], n = 3; medial, 43.3 ± 4.91, n = 3; dorsal, 40.3 ± 4.48, n = 3). p values for laminectomy versus DMSO: ventral, 0.12; medial, 0.98; dorsal, 0.17. p values for laminectomy versus PTPσ peptide: ventral, 0.16; medial, >0.99; dorsal, 0.81. p values for DMSO versus PTPσ peptide: ventral, 0.99; medial, 0.97; dorsal, 0.81. Representative traces of EMG recordings of the ventral region for laminectomy-only (D), hemisection plus DMSO-only (E), and hemisection plus PTPσ peptide (F). AAV2, adeno-associated virus serotype 2; CMAP, compound muscle action potential; CTB, cholera toxin subunit B; EMG, electromyography; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; PTPσ, protein tyrosine phosphatase σ; SCI, spinal cord injury;

Animals

Adult female Sprague-Dawley rats (250–300 g) were obtained from Taconic Farms. All animal procedures were approved by the Thomas Jefferson University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and conducted in compliance with ARRIVE (Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments) guidelines. We have optimized our injury paradigm, other surgical procedures, and diaphragm functional analyses in females. Nevertheless, we recognize the importance of performing our work in both sexes. Moving forward, we are also testing the peptide in males.

C2 hemisection spinal cord injury

Rats were anesthetized with ketamine HCl (95.0 mg/kg; Vedco, Saint Joseph, MO), xylazine (10.0 mg/kg; Lloyd Laboratories, Quezon City, Metro Manila, Philippines), and acepromazine (0.075 mg/kg; Phoenix Pharm Inc, Burlingame, CA). Hemisection was performed just caudal to the C2 dorsal root with a dissecting knife (Fine Science Tools, Foster City, CA), and a 30 gauge needle was passed through to ensure lesion completeness.12

Rostral ventral respiratory group injection

The caudal portion of the occipital bone was removed to reveal the obex. The rVRG was located relative to obex: 2.0 mm lateral, 0.5 mm rostral, and 2.6 mm ventral.13 An UltraMicroPump (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) injection system was used to deliver 0.3 μL of total volume with a microsyringe (Hamilton, Reno, NV) attached to a Micro4 Microsyringe Pump Controller (World Precision Instruments). AAV2-mCherry was used at 2.1 × 1013 GC/mL.

Electromyography recordings

For EMG recordings, animals were anesthetized with isoflurane inhalant anesthesia using the same conditions in all rats (1 LPM O2). A laparotomy was performed to expose the right hemidiaphragm. Bipolar recording electrodes spaced 3 mm apart were inserted into the diaphragm at dorsal, medial, or ventral subregions. Recordings during normal eupnic breathing were averaged over a continuous 60-sec time frame for each animal, and peak amplitude, burst duration, and frequency were taken. Every inspiratory burst over these 60 continuous sec was included in the analysis for both amplitude and frequency measurements. Using LabChart software (version 7; ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, CO), the EMG signal was amplified and filtered through a band-pass filter (50–3000 Hz).12

Compound muscle action potential recordings

Rats were anesthetized with isoflurane and stimulating electrodes were transcutaneously inserted near the passage of the phrenic nerve.14 A recording surface electrode was placed over the right rib cage. The phrenic nerve was stimulated between 10 and 20 times with a single burst at 6 mV (amplitude) for a 0.5-ms duration, and recordings were averaged for analysis. The ADI Powerlab8/30stimulator and BioAMPamplifier (ADInstruments) were used for both stimulation and recording, and Scope 3.5.6 (version 3.5.6; ADInstruments) was used for subsequent data analysis.

Immunohistochemistry

First, 30 μm, 4% paraformaldehyde-fixed sections were immunostained according to standard protocols.12 Primary antibodies included: anti–glial fibrillary acidic protein at 1:400 (Dako, Carpinteria, CA; RRID: AB_10013482); anti-5-HT (5-hydroxytryptamine) at 1:500 (Immunostar, Hudson, WI; RRID: AB_572263); anti-DsRed at 1:500 (Clontech Laboratories, Inc. Mountain View, CA; RRID:AB_10013483); and anti-CTB (cholera toxin subunit beta) at 1:10,000 (List Biological Laboratories, Campbell, CA). Secondary antibodies included: donkey antimouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) H&L (Alexa Fluor 488) at 1:200 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA), Rhodamine (TRITC) AffiniPure donkey antigoat IgG (H+L) at 1:200 (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA), donkey antirabbit IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor 647) at 1:200 (Abcam), and donkey antigoat IgG antibody (DyLight® 405) at 1:200 (Jackson ImmunoResearch).

Rostral ventral respiratory group axon quantification

For mCherry tracer quantification, sagittal spinal cord sections were imaged using a Zeiss Axio M2 Imager (Carl Zeiss Inc., Thornwood, NY). For the rVRG axon regeneration analysis (i.e., when axons are labeled from the ipsilateral rVRG), we quantified directed axon growth into and through the lesion site and caudally across the PhMN pool in the caudal intact spinal cord. To do this, we performed the counts of regrowing mCherry-labeled rVRG axon profiles in 100-um-wide (in the rostral-caudal axis) bins at specific distances from the rostral intact-lesion border.12 For the rVRG sprouting analysis (i.e., when axons are labeled from the contralateral rVRG), we quantified sprouting of axons—by counting the number of mCherry+ axon profiles—ipsilateral to the hemisection at three defined distances from the rostral end of the lesion that correspond approximately to the location of PhMNs in the C3, C4, and C5 spinal cord.

5-Hydroxytryptamine axon quantification

5-HT axons were identified by immunostaining in sagittal sections of the spinal cord, as described above. 5-HT fiber length was traced using Metamorph software in the ventral gray matter at distances 1.5, 3.0, and 4.5 mm caudal to the lesion-caudal intact border. Lengths of fibers were averaged at each location, and eight sections of tissue were analyzed for each animal.

Diaphragm whole-mount histology

Right hemidiaphragm was excised and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA). Diaphragms were labeled for neuromuscular junction (NMJ) markers, as described previously,15 using the following: α-bungarotoxin conjugated to Alexa Fluor 555 at 1:200 (Life Technologies, Waltham, MA; RRID: AB_2313931), anti-SV2 at 1:10 (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Iowa City, IA; RRID: AB_2314906), and neurofilament marker anti-SMI312 at 1:1000 (BioLegend, San Diego, CA; RRID: AB_2566782). Fluorescein isothiocyanate antimouse IgG secondary (1:100; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) was used as the secondary antibody.

Neuromuscular junction analysis

Diaphragms were analyzed for several NMJ morphologies, as described previously.16 Each NMJ was classified as intact, partially denervated, or completely denervated. Whole-mounted diaphragms were imaged on a FluoView FV1000 confocal microscope (Olympus, Center Valley, PA).

Statistical analysis

In the figure legends, we provide details of exact ns, group means, standard error of the mean, statistical tests used, and the results of all statistical analyses (including exact p values, t values, and F values) for each experiment and for all statistical comparisons. Statistical significance was assessed by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and multiple comparisons (Tukey) post-hoc test. A t-test was used for analysis involving only two conditions. Graphpad Prism software (version 6; Graphpad Software Inc.; La Jolla, CA; RRID: SCR_002798) was used for statistical analyses, and p < 0.05 was considered significant. PTPσ peptide studies were conducted on two separate cohorts to ensure reproducibility of the results. Each cohort consisted of 12 animals each (6 rats in each of the two groups) of similar age and weight. Both the EMG and rVRG axon growth analyses in these two studies showed similar results, and data were combined for all analyses. Two animals had to be removed from the study because of technical error: one because of incomplete hemisection and one because of mistargeted rVRG injection. For all quantification, we present the data as scatter plots to show the results for individual animals in each experimental condition.

Reagents

We authenticated regents to ensure they performed similarly across experiments and to validate resulting data. Whenever we generated in-house a new batch of AAV2-mCherry, we verified that virus performed equivalently from batch to batch by confirming in every animal that the vector transduced cells of the rVRG, transduced predominantly neuronal nuclei–positive neurons, and induced expression of mCherry tracer in the soma and axon projections of these cells. If viral delivery was mistargeted or failed to be expressed, we did not use the animal for analysis of rVRG axon regeneration or sprouting.

Results

Protein tyrosine phosphatase σ inhibition improved diaphragm function after cervical spinal cord injury without effects on diaphragm innervation

At 8 weeks after injury, we conducted EMG recordings at three subregions of the hemidiaphragm (ventral, medial, and dorsal) to assess effects on inspiratory diaphragm activation in vivo during eupnic breathing. EMG recordings show that amplitudes of inspiratory bursts were significantly greater with PTPσ peptide (Fig. 1B,F) compared to DMSO-only (Fig. 1B,E). Further, this recovery reached 40–75% of laminectomy-only uninjured control (Fig. 1B,D). The frequency of inspiratory bursts was unaltered by PTPσ peptide treatment compared to DMSO and laminectomy cohorts (Fig. 1C).

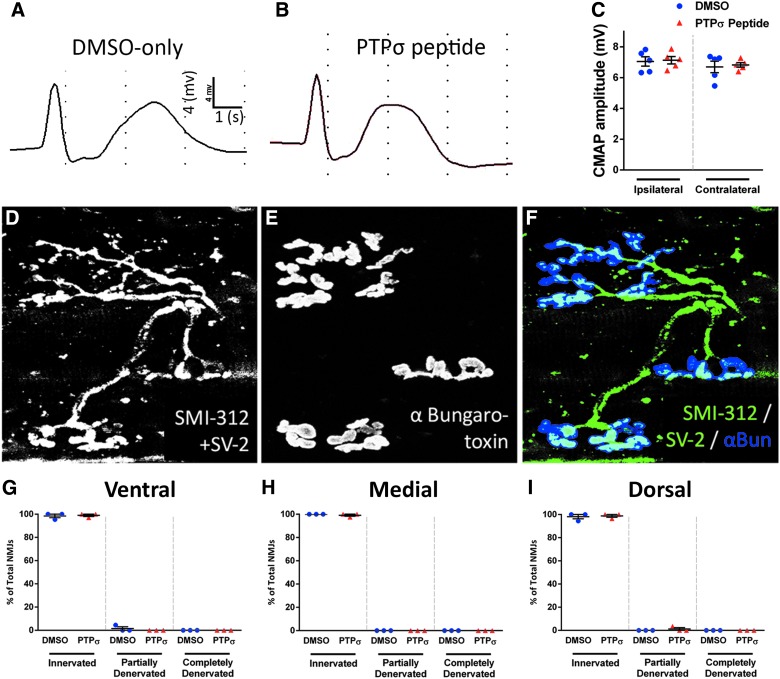

To determine potential effects on diaphragm innervation by PhMNs, we recorded CMAPs in each hemidiaphragm in vivo after supramaximal stimulation of the phrenic nerve. There were no differences in CMAP amplitude between DMSO-only (Fig. 2A) and PTPσ peptide (Fig. 2B) in both the ipsi- and contralateral hemidiaphragm, and CMAP amplitudes were also similar between the ipsi- and contralateral hemidiaphragm in both DMSO and PTPσ peptide groups (Fig. 2C). We next examined morphological innervation of the ipsilateral hemidiaphragm NMJ by phrenic motor axons using whole-mount analysis with the axon marker, SMI-312 (Fig. 2D,F), pre-synaptic terminal marker SV-2 (Fig. 2D,F), and post-synaptic nicotinic acetylcholine receptor label α-bungarotoxin (Fig. 2E,F). There were no differences between DMSO-only and PTPσ peptide in the percentage of NMJs that were intact, partially denervated, or completely denervated, with the vast majority of NMJs being completely intact across all three diaphragm subregions: ventral (Fig. 2G), medial (Fig. 2H), and dorsal (Fig. 2I). These data demonstrate that PTPσ inhibition did not affect functional or morphological innervation of the diaphragm, suggesting that functional EMG effects of the peptide were induced by plasticity mechanisms centrally within the cervical spinal cord.

FIG. 2.

PTPσ inhibition did not alter diaphragm NMJ morphology after SCI. Representative CMAP traces of ipsilateral hemidiaphragm of DMSO-only (A) and PTPσ peptide groups (B) and CMAP quantification show no difference in peak amplitude between groups on the ipsilateral side (ipsi DMSO, 7.048 ± 0.303 mV, n = 5; ipsi PTPσ peptide, 7.128 ± 0.239, n = 5; p > 0.999; contra DMSO, 6.694 ± 0.377, n = 5; contra PTPσ peptide, 6.824 ± 0.145, n = 5; p = 0.999, ANOVA) and between the ipsi- and contralateral sides in both groups (DMSO ipsi vs. DMSO contra, p = 0.945; PTPσ peptide ipsi vs. PTPσ peptide contra, p = 0.973, ANOVA; C). Diaphragm NMJs were labeled with SMI-312 (D and F), SV-2 (D and F), and α-bungarotoxin (E and F); scale bar, 50 μm. Nearly all NMJs were completely intact (D and G–I). Quantification of NMJ morphologies shows that PTPσ peptide had no effect on the percentage of NMJs that were intact, partially denervated, or completely denervated in all subregions of the diaphragm: ventral (G), medial (H), and dorsal (I; n = 3 per group). α-Bun, α-bungarotoxin; ANOVA, analysis of variance; CMAP, compound muscle action potential; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; NMJ, neuromuscular junction; PTPσ, protein tyrosine phosphatase σ; SCI, spinal cord injury.

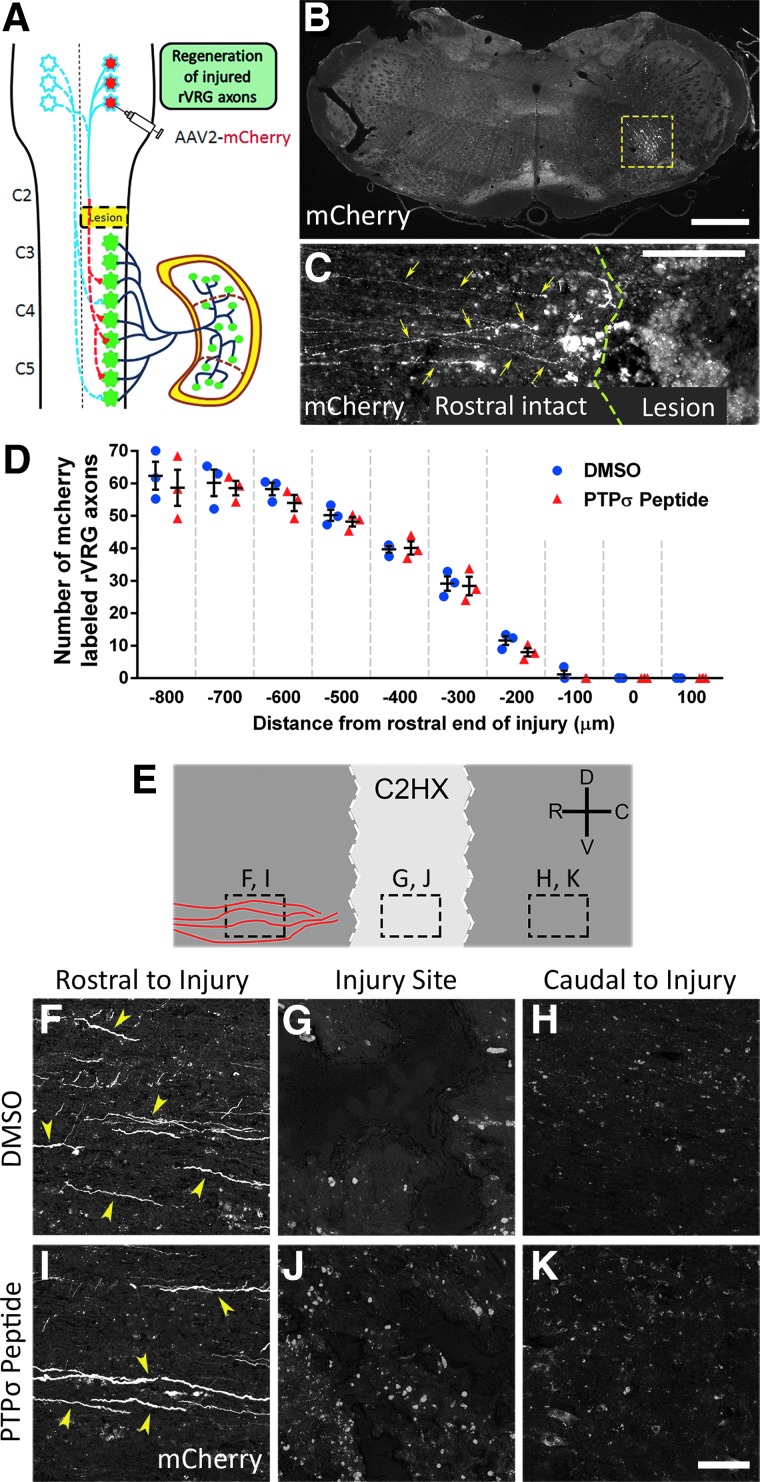

Protein tyrosine phosphatase σ inhibitory peptide did not promote regeneration of damaged respiratory axons after cervical spinal cord injury

To explore the modes of circuit plasticity associated with diaphragm recovery after PTPσ inhibition, we injected the AAV2-mCherry anterograde tracer into the ipsilateral (Fig. 3A) or contralateral (Fig. 4A) rVRG in two separate cohorts. Similar to our previous report, AAV2-mCherry transduction was efficient and localized to the rVRG in either the ipsilateral (Fig. 3B) or contralateral (Fig. 3B) medulla.12 For analysis of ipsilateral rVRG axon regrowth, we quantified the number of labeled rVRG axons in 100 (μm) bins in sagittal sections using the rostral end of the injury as the starting point. There was no regeneration of injured axons originating in the ipsilateral rVRG in response to PTPσ peptide, similar to DMSO-only control (Fig. 3C,D). We never observed rVRG axons extending through the rostral intact-lesion interface in either group, with most of these axons retracting from the rostral lesion border (Fig. 3C,D). High-magnification imaging shows mCherry-labeled rVRG axons at three locations of the ipsilateral spinal cord (Fig. 3E): rostral to injury, injury site, and caudal to injury. Both the PTPσ peptide and DMSO groups showed descending ipsilateral axons present rostral to the injury (Fig. 3F,I), but no axons extending into the injury site (Fig. 3G,J) or into the caudal intact spinal cord (Fig. 3H,K), showing that PTPσ treatment had no effect on rVRG axon regeneration. These results suggest that rVRG axon regeneration was not responsible for functional diaphragm recovery induced by PTPσ peptide.

FIG. 3.

PTPσ peptide treatment did not promote ipsilateral rVRG axon regeneration. Schematic of the AAV2-mCherry tracer injection into the ipsilateral rVRG (A). The 30-μm coronal section of the medulla shows the location and efficiency of the AAV2-mCherry injections into the ipsilateral rVRG, outlined by the dotted yellow box (B); scale bar, 450 μm. Representative image of the 30-μm sagittal section from the PTPσ peptide-treated rat injected with AAV2-mCherry into the ipsilateral rVRG: No mCherry-labeled rVRG axons regenerate across the rostral intact-lesion border into the injury site (C); scale bar, 200 μm; yellow arrows indicate mCherry-labeled rVRG axons, and green line shows the rostral border of the lesion. Quantification shows lack of regeneration of ipsilateral-originating mCherry-labeled rVRG axons in both DMSO-only and PTPσ peptide groups (D); p = 0.119; F(1, 40) = 2.543, Tukey's post-test; ANOVA; n = 3 per group. Schematic of sagittal section of the cervical spinal cord labeled with AAV2-mCherry of ipsilateral rVRG projections show the locations of high-magnification images (E). Representative images of mCherry-labeled rVRG axons within the 30-μm sagittal spinal cord sections of DMSO- (F–H) and PTPσ peptide–treated (I–K) animals. Rostral regions show no differences in mCherry-labeled fibers between DMSO- and PTPσ peptide–treated animals (F and I); yellow arrows denote mCherry-labeled axons; scale bar, 100 μ. No mCherry-labeled rVRG axon growth was present in either the injury site (G and J) or caudal intact regions of the spinal cord (H and K); scale bar, 100 μm. AAV2, adeno-associated virus serotype 2; ANOVA, analysis of variance; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; PTPσ, protein tyrosine phosphatase σ; rVRG, rostral ventral respiratory group.

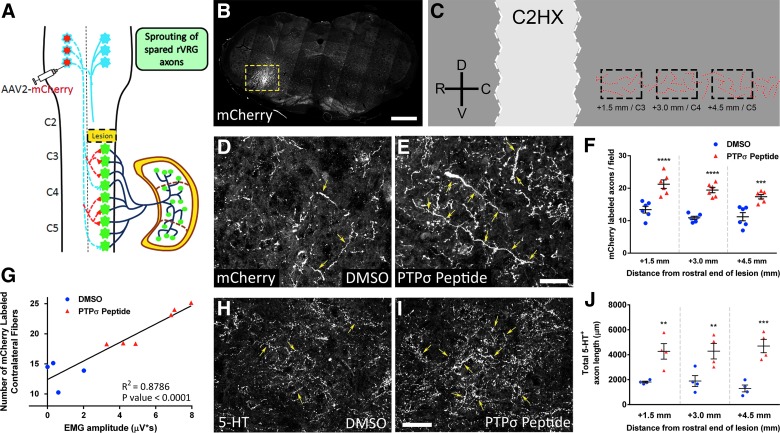

FIG. 4.

PTPσ inhibitory peptide induced robust sprouting of spared bulbospinal respiratory axons after cervical SCI. Schematic of the AAV2-mCherry tracer injection into the contralateral rVRG (A). The 30-μm coronal section of the medulla shows the location and efficiency of the AAV2-mCherry injections into the contralateral rVRG, outlined by the dotted yellow box (B); scale bar, 450 μm. Schematic of sagittal section of the cervical spinal cord shows locations of quantified mCherry-labeled contralateral rVRG projections in the C3–C5 regions of the ipsilateral spinal cord tissue (C). In animals labeled with AAV2-mCherry from the contralateral rVRG, there was a pronounced increase in the density of rVRG axons within the C3–C5 ventral horn ipsilateral to the lesion in the PTPσ peptide group (E) compared to DMSO-only (D); scale bar, 100 μm. Yellow arrows denote mCherry-labeled rVRG axons within the ipsilateral PhMN pool. Quantification of rVRG axon sprouting (F): +1.5 mm (DMSO, 13.41 ± 1.04 mCherry+ axon profiles, n = 6; PTPσ peptide, 21.24 ± 1.31, n = 6; p < 0.0001, ANOVA); +3.0 mm (DMSO, 10.88 ± 0.49, n = 6; PTPσ peptide: 19.43 ± 0.83, n = 6; p < 0.0001, ANOVA); and +4.5 mm (DMSO, 11.21 ± 1.26, n = 6; PTPσ peptide, 17.39 ± 0.68, n = 6; p = 0.0003, ANOVA). Functional EMG recovery (in the ventral subregion) was correlated with degree of the rVRG axon sprouting response (G). Compared to DMSO-only (H), PTPσ peptide (I) increased total serotonergic axon length within the ipsilateral ventral horn at C3 (1.5 mm caudal), C4 (3.0 mm), and C5 (4.5 mm; J); scale bar, 100 μm (+1.5 mm; DMSO, 1810.25 ± 73.00 μm, n = 4; PTPσ peptide, 4271.75 ± 623.03 μm, n = 4; p = 0.0050, ANOVA); (+3.0 mm; DMSO, 1890.00 ± 439.73 μm, n = 4; PTPσ peptide, 4285.00 ± 620.77 μm, n = 4; p = 0.0063, ANOVA); and (+4.5 mm; DMSO, 1295.75 ± 275.47 μm, n = 4; PTPσ peptide, 4698.75 ± 536.06 μm, n = 4; p = 0.0002, ANOVA). AAV2, adeno-associated virus serotype 2; ANOVA, analysis of variance; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; EMG, electromyography; PhMN, phrenic motor neuron; PTPσ, protein tyrosine phosphatase σ; rVRG, rostral ventral respiratory group; SCI, spinal cord injury.

Protein tyrosine phosphatase σ inhibitory peptide induced robust sprouting of spared bulbospinal respiratory axons after cervical spinal cord injury

We next assessed sprouting of spared rVRG axons originating in the contralateral medulla (Fig. 4A,B). Compared to DMSO-only (Fig. 4D), PTPσ peptide (Fig. 4E) promoted a significant increase in the density of mCherry-labeled rVRG axon projections specifically within the ventral horn ipsilateral to the hemisection at levels C3 (1.5 mm), C4 (3.0 mm), and C5 (4.5 mm; Fig. 4C,F), the location of PhMNs. Further, functional EMG recovery was correlated with the degree of the rVRG axon sprouting response (Fig. 4G). These data suggest that PTPσ inhibition may have promoted recovery of diaphragm function by stimulating sprouting of spared rVRG axons that descend in the intact contralateral spinal cord.

We also assessed growth of serotonergic axons that play an important role in modulating PhMN excitability during diaphragm activation. Compared to DMSO-only (Fig. 4H), PTPσ peptide (Fig. 4I) increased the total length of 5-HT axons within the ipsilateral ventral horn at levels C3, C4, and C5 (Fig. 4J).

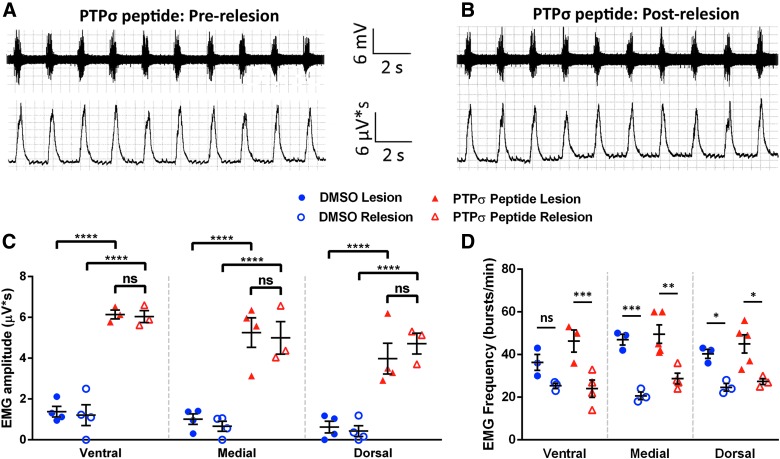

To further explore the contribution to functional recovery of regeneration through the lesion versus input from spared pathways originating in the contralateral spinal cord, we performed a relesion through the hemisection site of PTPσ peptide– and DMSO-only–treated animals. Importantly, this relesion study was performed with a separate cohort several months after the initial experiment; the robust functional EMG recovery was fully recapitulated in these animals in response to PTPσ peptide. Immediately after the relesion, EMG recordings were again obtained from the same animals. Quantification of EMG inspiratory burst amplitude from PTPσ peptide–treated animals pre-relesion (Fig. 5A) and after relesion (Fig. 5B) show no loss of EMG amplitude compared to their within-animal pre-relesion levels at all three diaphragm subregions (Fig. 5C), suggesting that functional recovery was driven by plasticity of spared contralateral input. Interestingly, we observed that relesion reduced inspiratory burst frequency in both the peptide and DMSO-only groups at all three diaphragm subregions (Fig. 5D), despite not finding an effect of relesion on EMG amplitude in any of these conditions.

FIG. 5.

Relesion did not affect PTPσ peptide-induced diaphragm EMG activity. Representative EMG traces show that, compared to pre-relesion (A), relesion did not affect inspiratory burst amplitudes in PTPσ peptide–treated animals (B). Quantification of EMG amplitudes before and after relesion (C): ventral (DMSO pre-relesion, 1.375 ± 0.26 μV*s, n = 4; DMSO post-relesion: 1.21 ± 0.51, n = 4; PTPσ peptide pre-relesion, 6.14 ± 0.22, n = 3; PTPσ peptide post-relesion, 6.04 ± 0.29, n = 3); medial (DMSO pre-relesion: 1.01 ± 0.26, n = 4; DMSO post-relesion, 0.66 ± 0.25, n = 4; PTPσ peptide pre-relesion: 5.25 ± 0.73, n = 4; PTPσ peptide post-relesion: 4.99 ± 0.79, n = 3); dorsal (DMSO pre-relesion, 0.63 ± 0.29, n = 4; DMSO post-relesion: 0.43 ± 0.27, n = 4; PTPσ peptide pre-relesion: 3.98 ± 0.75, n = 4; PTPσ peptide post-relesion: 4.71 ± 0.51, n = 3); DMSO pre-relesion versus post-relesion (ventral, p = 0.99, medial, p = 0.95, dorsal, p = 0.99); and PTPσ peptide pre-relesion versus post-relesion (ventral, p > 0.99; medial, p = 0.98; dorsal, p = 0.72). Burst frequency in ipsilateral hemidiaphragm before and after relesion in DMSO and PTPσ peptide groups at the three diaphragm subregions (D). DMSO (ventral, 36.3 ± 3.76 [bursts/min], n = 3; medial, 47.0 ± 2.52, n = 3; dorsal, 40.3 ± 2.19, n = 3); DMSO relesion (ventral, 25.3 ± 1.20, n = 3; medial, 20.7 ± 1.76, n = 3; dorsal: 24.7 ± 1.76, n = 3); PTPσ peptide (ventral, 46.3 ± 5.24, n = 3; medial, 47.0 ± 4.42, n = 4; dorsal, 44.0 ± 5.51, n = 3); and PTPσ peptide relesion (ventral, 21.0 ± 3.79, n = 3; medial, 28.8 ± 2.56, n = 4; dorsal, 27.3 ± 1.45, n = 3). DMSO pre-relesion versus post-relesion (ventral, p = 0.02; medial, p < 0.01; dorsal, p < 0.01); PTPσ peptide pre-relesion versus post-relesion (ventral, p = 0.02; medial, p = 0.05; dorsal, p = 0.12). DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; EMG, electromyography; ns, not significant; PTPσ, protein tyrosine phosphatase σ.

Discussion

These findings reveal a mode of rVRG-PhMN-diaphragm circuit plasticity that likely can drive recovery of diaphragm function after cervical SCI, namely sprouting of the rVRG axons spared by the injury. Given the anatomical preservation (particularly of white matter) that occurs in most clinical SCI cases,17 this form of bulbospinal axon growth and circuit connectivity is a relevant substrate for repair and respiratory recovery. Further, given the difficult challenge of promoting long-distance regeneration of injured rVRG axons into and through (or around) the lesion to then synaptically reconnect with their PhMN targets, stimulating relatively short-distance local sprouting of rVRG fibers—that are already present within intact C3–C5 ventral horn caudal to the lesion18—represents a therapeutic goal that is more easily achievable.

We recently demonstrated that inhibition of phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), a neuronal-intrinsic regulator of axon growth capacity, using a similar peptide-based strategy, also promoted significant recovery of diaphragm function in the C2 hemisection model (Urban and Ghosh and colleagues, eNeuro, in press). Unlike the current work with PTPσ peptide, PTEN antagonist peptide administration instead promoted robust regeneration of injured ipsilateral-originating rVRG axons and synaptic reconnectivity of these regrowing axons with PhMNs located caudal to the lesion. Further, relesion (utilizing the same paradigm as in the current study) completely ablated all functional diaphragm recovery, unlike the lack of effect we observed with relesion of PTPσ peptide–treated rats. Together, these findings demonstrate that multiple modes of rVRG axon plasticity and rVRG-PhMN-diaphragm circuit connectivity can promote recovery of diaphragm function after SCI. Our findings also suggest that combination of PTPσ and PTEN inhibition may result in particularly robust therapeutic efficacy through additive—or even synergistic—effects.

Although our anatomical tracing data support the notion that sprouting of spared rVRG axons was responsible for the observed functional recovery in response to PTPσ peptide, we have not causally established this relationship. The relesion results demonstrate that functional recovery was completely based on input from the spared contralateral spinal cord; however, neuronal populations in addition to (or instead of) contralateral-originating rVRG axons may have been responsible for driving recovery. In particular, descending serotonergic input has been shown to play an important role in PhMN activation. Interestingly, we also observed robust effects on serotonergic axon sprouting within the PhMN pool on the side of injury, suggesting that the functional effects of PTPσ peptide administration were also attributed to serotonergic axon plasticity. Though further analysis of this circuit recovery needs to conducted, we hypothesize that increases in PhMN innervation by both modulatory serotonergic and excitatory rVRG axons together mediated effects on PhMN activation and diaphragm recovery. Further, our serotonergic axon sprouting findings are in line with a previous study that used a similar PTPσ peptide approach in the thoracic contusion SCI model 9; in this study, the researchers observed enhanced serotonergic axon growth caudal to the lesion, which likely contributed to recovery of both locomotor and bladder function. Similarly, a recent study by Warren and colleagues utilized chondroitinase ABC to degrade CSPGs at acute and chronic time points after cervical SCI.19 The researchers reported robust respiratory recovery after treatment in animals even up to 1.5 years after injury, and they also showed that plasticity of serotonergic input to the PhMN pool may underlie, at least in part, this functional effect.

Our findings and other studies raise the question of why PTPσ inhibition stimulated local sprouting of rVRG axons, but not regeneration of injured fibers. In the context of the rVRG-PhMN circuit, it is possible that differential levels of expression of PTPσ ligands may be responsible. Whereas previous work (as well as our own findings: data not shown) has shown that axon growth inhibitors such as CSPGs are upregulated after cervical SCI within the intact PhMN pool caudal to the lesion,20 the degree of upregulation of CSPGs (and likely other axon growth inhibitors) is significantly less than inside and directly surrounding the lesion site. Even with administration of PTPσ peptide, it is possible that injured rVRG axons could not overcome this more pronounced expression of growth inhibitors as they encountered the injury site.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that inhibition of PTPσ receptor signaling can promote significant recovery of diaphragmatic respiratory function after cervical SCI by stimulating plasticity of critical axon populations spared by the injury and consequently enhancing descending excitatory input to PhMNs.

Funding Information

This work was supported by the NINDS (2R01NS079702-06 to A.C.L.; 1F30NS103436 to B.A.C.), Craig H. Neilsen Foundation (grant 476686 to A.C.L.), and Shriners Hospitals for Children (SHC 84051 to G.M.S.).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1. Huber A.B., Weinmann O., Brösamle C., Oertle T., and Schwab M.E. (2002). Patterns of Nogo mRNA and protein expression in the developing and adult rat and after CNS lesions. J. Neurosci. 22, 3553–3567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Baldwin K.T., and Giger R.J. (2015). Insights into the physiological role of CNS regeneration inhibitors. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 8, 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Trapp B.D., Andrews S.B., Cootauco C., and Quarles R. (1989). The myelin-associated glycoprotein is enriched in multivesicular bodies and periaxonal membranes of actively myelinating oligodendrocytes. J Cell Biol 109, 2417–2426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wang K.C., Koprivica V., Kim J.A., Sivasankaran R., Guo Y., Neve R.L., and He Z. (2002). Oligodendrocyte-myelin glycoprotein is a Nogo receptor ligand that inhibits neurite outgrowth. Nature 417, 941–944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shen Y.T., Tenney A.P., Busch S.A., Horn K.P., Cuascut F.X., Liu K., He Z., Silver J., and Flanagan J.G. (2009). PTPsigma is a receptor for chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan, an inhibitor of neural regeneration. Science 326, 592–596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bradbury E.J., Moon L.D., Popat R.J., King V.R., Bennett G.S., Patel P.N., Fawcett J.W., and McMahon S.B. (2002). Chondroitinase ABC promotes functional recovery after spinal cord injury. Nature 416, 636–640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Crespo D., Asher R.A., Lin R., Rhodes K.E., and Fawcett J.W. (2007). How does chondroitinase promote functional recovery in the damaged CNS? Exp. Neurol. 206, 159–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cafferty W.B., Yang S.H., Duffy P.J., Li S., and Strittmatter S.M. (2007). Functional axonal regeneration through astrocytic scar genetically modified to digest chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans. J. Neurosci. 27, 2176–2185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lang B.T., Cregg J.M., DePaul M.A., Tran A.P., Xu K., Dyck S.M., Madalena K.M., Brown B.P., Weng Y.L., Li S., Karimi-Abdolrezaee S., Busch S.A., Shen Y., and Silver J. (2015). Modulation of the proteoglycan receptor PTPsigma promotes recovery after spinal cord injury. Nature 518, 404–408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rink S., Arnold D., Wöhler A., Bendella H., Meyer C., Manthou M., Papamitsou T., Sarikcioglu L., and Angelov D.N. (2018). Recovery after spinal cord injury by modulation of the proteoglycan receptor PTPσ. Exp. Neurol. 309, 148–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sharma H., Alilain W.J., Sadhu A., and Silver J. (2012). Treatments to restore respiratory function after spinal cord injury and their implications for regeneration, plasticity and adaptation. Exp. Neurol. 235, 18–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Urban M.W., Ghosh B., Strojny L.R., Block C.G., Blazejewski S.M., Wright M.C., Smith G.M., and Lepore A.C. (2018). Cell-type specific expression of constitutively-active Rheb promotes regeneration of bulbospinal respiratory axons following cervical SCI. Exp. Neurol. 303, 108–119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lipski J., Zhang X., Kruszewska B., and Kanjhan R. (1994). Morphological study of long axonal projections of ventral medullary inspiratory neurons in the rat. Brain Res. 640, 171–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nicaise C., Hala T.J., Frank D.M., Parker J.L., Authelet M., Leroy K., Brion J.P., Wright M.C., and Lepore A.C. (2012). Phrenic motor neuron degeneration compromises phrenic axonal circuitry and diaphragm activity in a unilateral cervical contusion model of spinal cord injury. Exp. Neurol. 235, 539–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wright M.C., and Son Y.J. (2007). Ciliary neurotrophic factor is not required for terminal sprouting and compensatory reinnervation of neuromuscular synapses: re-evaluation of CNTF null mice. Exp. Neurol. 205, 437–448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ghosh B., Wang Z., Nong J., Urban M.W., Zhang Z., Trovillion V.A., Wright M.C., Zhong Y., and Lepore AC. (2018). Local BDNF delivery to the injured cervical spinal cord using an engineered hydrogel enhances diaphragmatic respiratory function. J. Neurosci. 38, 5982–5995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McDonald J.W., and Becker D. (2003). Spinal cord injury: promising interventions and realistic goals. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 82, 10 Suppl., S38–S49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lane M.A., Lee K.Z., Fuller D.D., and Reier P.J. (2009). Spinal circuitry and respiratory recovery following spinal cord injury. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 169, 123–132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Warren P.M.S., Steiger S.C., Dick T.E., MacFarlane P.M., Alilain W.J., and Silver J. (2018). Rapid and robust restoration of breathing long after spinal cord injury. Nat. Commun. 9, 4843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Alilain W.J., Horn K.P., Hu H., Dick T.E., and Silver J. (2011). Functional regeneration of respiratory pathways after spinal cord injury. Nature 475, 196–200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]