Short abstract

Objective

To analyse how staff in one Scottish hospital respond to anonymised patient feedback posted on the nationally endorsed feedback platform Care Opinion; and to understand staff experiences of, and attitudes towards, engaging with Care Opinion data.

Methods

This was a multi-method study comprising: (a) numerical and thematic analysis of stories posted during a six-month period, using a published framework; (b) thematic analysis of interviews with a range of 10 hospital staff responsible for organisational responses to feedback.

Results

Seventy-seven stories were published during the six-month period. All received a response, with a mean response time of 3.9 days. Ninety-six responses were made in total, from 20 staff members. Personalisation and tailoring was mostly assessed as performing well against the published framework. Only two ‘changes made’ were reported. While staff interviewed were mostly understanding of why patients might prefer giving anonymised feedback, some found it uncomfortable and challenging. Participants described instances where they might seek to de-anonymise the individual, in order to pass on personal thanks to the relevant staff member, or to investigate the issue raised and seek resolution offline. Patients did not always want to identify themselves; this could sometimes lead staff to query the veracity or importance of issues raised. Sometimes staff could identify individuals anyway, including one described as ‘our regular person’.

Conclusions

Staff used to engaging directly with patients and families, both clinically and in dealing with feedback, need support in dealing with anonymous feedback, and the uncomfortable situation of unequal power it may create.

Keywords: Patient experience, patient feedback, online feedback, qualitative research, NHS staff, anonymity, power, Care Opinion

Introduction

One consequence of the rapid growth of social media and internet use in the last decade is the opening up of multiple new ways for people to comment on healthcare they have received (or not). These range from nationally organised ratings and comments systems, to social media accounts run by individual healthcare organisations, to personal blogs, tweets and Facebook posts. This is a complex landscape, with healthcare providers facing a wave of platforms and sources of feedback, some organisationally sanctioned and moderated, others organic and uncontrolled.

Duschinsky and Paddison1 have charted the increasing focus in the UK on patient experience as an aspect of quality, and identify a range of potentially conflicting ‘causal processes’ behind it. For example, they question whether the focus on patient experience is about valuing patients’ expertise and using it for improvement or, rather, about maintaining the reputation and financial performance of healthcare organisations. Similarly they ask whether patient surveys are designed for internal hierarchical performance management or for creating public transparency, and whether this apparent concern for transparency does ‘serve as a ritual of consultation’ (p.102).

It is of course possible to be concerned both about defending organisational reputation and about improving the quality of patients’ experience by listening to and acting on their concerns. Indeed, arguably the latter can support the former; there is a growing evidence base that organisations which score well on measures of patient-centredness also perform well on other measures of organisational success.2–6 By contrast, Nagraj et al.7 demonstrate that general practices which perform poorly on doctor–patient communication are more likely to lose patients through voluntary disenrolment.

However, as Dudhwala and colleagues8 have argued, engaging with the plethora of forms and sources of online feedback is not straightforward. They argue that it is hard for staff to engage with feedback unless it is organisationally sanctioned, solicited (consistently asked for from patients or carers) and sought (actively searched for and used).

In other words, they suggest that healthcare organisations determine and shape what counts as legitimate, actionable online feedback, and what feedback is seen as irrelevant or unreliable. The reaction to online feedback has much in common with organisational responses to other more conventional forms of qualitative feedback. As Martin et al.9 have noted, senior hospital managers recognise the potential value of so-called ‘soft intelligence’, but struggle to work out ‘how to process such a detailed, frustrating, rich, and irreducibly complex resource’ (p.24). Managers in their study adopted various strategies for channelling and ‘taming’ feedback, for example systematising it by proactively collecting feedback rather than relying on naturally occurring, unprompted feedback from patients, family carers and staff; seeking to triangulate it with other more quantitative data sources; and aggregating it, looking for key themes and patterns. The purpose of such aggregation was for the organisation to distinguish data suggesting that investigation and action were required from ‘one-off incidents’.

The urge to impose structure and control, Martin et al.9 argue, may have unintended consequences – not only by reducing rich, untamed complexity to decontextualised data which is manageable but lacks useful detail, but also by prioritising majority views. If repeated and widely held views are seen as more credible, reliable and valid than ‘the exceptional views expressed by the few … serious problems with the quality of care might be missed’ (p.24).

At the same time, aggregation of online feedback holds some promise. Griffiths and Leaver10 used an automated tracking system to combine patient feedback from NHS Choices, Care Opinion, Facebook and Twitter to form a ‘collective judgement score’ and compared the result with the outcome of organisational inspections by the UK regulator, the Care Quality Commission. They found a positive association between the collective judgement score and subsequent inspection outcomes (whether the organisation was rated as inadequate; requires improvement; good or outstanding). They suggest that such a collective judgement score could be used to identify a high-risk group of organisations for inspection.

The opportunity to give online feedback has been hailed as an equalising mechanism, enabling people to give feedback at a time of their own choosing, in their own words, often unmoderated and often anonymous.11 However, as Speed et al.11 note, while patients may welcome the protection and freedom afforded by anonymity in online posting, healthcare providers may find this shift in the balance of power uncomfortable and challenging. They note that professionals see patient anonymity as a barrier to effective use of feedback, and a risk to the reputation of individual practitioners or organisations, given that anyone can say anything, no matter how unfair or damaging. Meanwhile patients fear that being identifiable may compromise the care they receive if they make critical remarks. This constitutes an ‘anonymity paradox’, whereby patients see anonymity as a prerequisite but professionals see it as a barrier.

Care Opinion and Care Opinion Scotland

The online feedback in the study by Speed et al.11 was an unmoderated blogging space set up as part of the research study. The need for moderation is one of their key recommendations, and/or verification of identity by the website managers. In our study, we focus on Care Opinion, a moderated independent website for patient feedback.

Care Opinion was set up in the UK in 2005, and was originally known as Patient Opinion until 2017. It was deliberately independent of the National Health Service (NHS), to enable people to give feedback through a third party. It is a non-profit community interest company, funded mainly by subscriptions from healthcare organisations. Organisations which choose not to subscribe may still see and respond to patient feedback, but only two staff may be registered to do so. Subscribing organisations can register staff across the organisation to reply directly to people who post, and receive training and analytics support from Care Opinion.

People who use services, their relatives, carers or friends share stories anonymously in line with Care Opinion guidelines, using a screenname which they select. Every story is read by one (or more) member of the Care Opinion team and reviewed against the following principles:

Enable a clear, timely, public, constructive conversation about care;

Make giving feedback safe and easy for patients, service users and carers;

Encourage authentic feedback, based in personal experience;

Treat staff legally and fairly.

Once moderated, stories are published on the Care Opinion website and the aim is to simultaneously send email alerts about the story to the right section of the health and care service, who can then listen and respond.

Care Opinion has always operated across the UK but activity was primarily England focused until 2011, when a base was set up in Scotland. Care Opinion Ireland and Care Opinion Australia have also been established. Positive discussions are currently underway with the Department of Health in Northern Ireland for system wide use of Care Opinion. In England and Wales there is no formal support from the NHS, and individual healthcare (and increasingly social care) organisations make their own decision as to whether or not to subscribe.

NHS Scotland is run as a separate health service by the devolved Scottish Government; unlike England, there is no separation between commissioners and providers of healthcare, and instead all healthcare services in an area are planned and managed by integrated regional health boards. In 2014 NHS Scotland took a decision to invest centrally in funding Care Opinion subscriptions for all regional health boards who wanted to take up this option. This central contract was renewed in 2017–2018 for a further four years. At the time of writing only one board out of 17 patient facing health boards has opted out of this arrangement. Jason Leitch, national clinical director for healthcare quality and strategy for the Scottish Government, is on record as saying that ‘The use of Care Opinion is the most important single thing we’ve done around person-centred care in the last three years’.12

This has created a distinctive policy landscape for online feedback in Scotland, in which there is strong central encouragement for staff to engage with Care Opinion. Scottish boards regularly feature in the top 10 list of organisations with the most staff actively getting involved in responding to posts.

There is little published research on why people post on Care Opinion, how staff respond and what people feel about the responses they receive, although one major UK study on online feedback generally, including Care Opinion, (INQUIRE) is reporting soon.13 A survey conducted as part of that study14 found that people’s reasons for posting online reviews or comments are often more positive than assumed. The top three reasons for posting were to provide information for other patients (39%); to praise a service received (36%); and to improve standards of care in the NHS (15%). Providing praise was thus considerably more common than wanting to complain about a service (6%), treatment (5%) or professional (4%). This is confirmed by qualitative interview findings from INQUIRE, suggesting that online feedback is seen by those posting as primarily a means of expressing care for the NHS as a valued institution.15

Ziewitz16 has published an ethnography of the moderation process at Care Opinion, drawing on a period of in-depth participant observation as a researcher embedded as a moderator. He argues that the moderation process is not about ‘capturing’ patient experience as a set of facts, but is rather ‘an exercise in testing versions of reality’, as moderator and story author communicate back and forth in shaping the eventual post (p.99). The hidden labour of moderation is explored in some depth through the story of one post, as well as the not uncritical reaction of the poster to the editing of his story – the dilution of his story, as he sees it.

Baines et al.17 worked with mental health users to identify what they most wanted to see in staff responses to Care Opinion posts and to design and test a framework for evaluating the quality of response. Together they identified nineteen factors considered influential in response quality, centred around seven topic areas:

(a)Introductions (names, photo, addressing the individual);

(b)Explanations (your role, what you are responsible for, why you are replying);

(c)Speed of response (if not within seven days apologise and explain the delay);

(d)Thanks and apologies (thanking the person for their time; for positive feedback offering to pass it on; for negative feedback, apologising and listening to concerns);

(e)Response content (is it tailored to the individual post: have you stated how you will follow up?);

(f)Signposting (to other relevant services or staff members; with contact details and names; with more than one option for mode of further contact);

(g)Response sign‐off (polite and personal).

These form the Plymouth, Listen, Learn and Respond framework, which informed our analysis of staff responses (see Methods below).

More recently, Ramsey et al.18 have developed a typology of staff responses and identified their frequency in an analysis of 475 published on Care Opinion in March 2018:

Non-responses (11.8%) – no response received within three months;

Generic responses (10.5%) – copied and pasted stock organisational replies;

Appreciative responses (58.5%) – mainly thanks for positive stories, some thanks and apologies;

Offline responses (23.6%) – mainly replying to negative posts, seeking to take communication offline;

Transparent, conversational responses (6.5%) – demonstrating compassion, engaging with the issues.

Arguably the appreciative and the transparent, conversational response categories map onto the qualities of response preferred by users in the Plymouth Listen, Learn Respond Framework.

Aims

This was a multi-method study in which we aimed to explore who was responding and how on Care Opinion and then to use more in-depth qualitative research to understand staff views more generally.

In our small pilot study we set out to ask the following questions:

How do staff respond to stories on Care Opinion?

What are staff experience of and attitudes towards engaging with Care Opinion data?

How can staff at all levels be better supported to use Care Opinion feedback for improvement?

This study focused on a single general acute site in Scotland, local to the research team. Within Scotland this site is an average performer in terms of number of staff responders. Our pilot findings are now informing a Scotland-wide research study, including patient as well as staff experiences.

Methods

The research team comprised two qualitative social science researchers (ZS and LLo), a senior nurse manager (CH), the director of Care Opinion Scotland (GA), a medical student intern (JS) and a patient adviser (LLa). GA and LLa both advised on the development of the interview topic guide at the start of the study and got involved in analysis (see below).

Analysis of Care Opinion responses

All patient feedback stories regarding Aberdeen Royal Infirmary (ARI) published on Care Opinion, in the six month period between December 2017 and May 2018, were identified and analysed. We made a pragmatic decision about sampling a manageable amount of data for analysis within the study timeframe. We also chose to include the winter period when pressures on services are greatest and more comments might be expected. Data on both the story itself and its associated staff response(s) were collected and analysed using the ‘Plymouth Listen, Learn and Respond Framework’ (LLRF) categories developed by Baines et al.17

To our knowledge, this is the first time the framework has been applied to staff responses to Care Opinion in an acute setting, beyond its original use in mental health services. Following our initial quality appraisal, we observed a few additional aspects to responses within our sample which did not seem to be fully represented by the framework. Therefore, responses were subsequently assessed against these further factors, which we report below.

Interviews with ARI staff

Email invitations were sent to a range of staff identified as responders from our sample of December 2017 to May 2018 and other staff members registered as responders to Care Opinion on behalf of the hospital. Our sampling was purposive, encompassing a mix of more and less experienced responders, and people in nursing, management and patient feedback roles. The identification of prospective interviewees was also facilitated by the initial analysis of patient feedback stories.

Ten staff members agreed to be interviewed. All were active responders to (and/or readers of) Care Opinion postings. Recruitment was slow; we had planned to interview up to 15 staff. Despite assurances that staff would be anonymised, we speculate that awareness that the study was being conducted in one hospital and concerns about identifiability may have created barriers to participation. (This is in itself noteworthy in the light of our findings discussed below about anonymity and feelings of vulnerability.)

Interviews were analysed thematically using a combination of anticipated themes (informed by the LLRF and our research questions), as well as inductively derived coding. To inform coding, we involved LLa as our patient partner, using an ‘analytic conversation’ approach. This approach aims ‘to elicit user reflections on their experience at the start of analysis, and use this as a guide to direct both researcher and service user attention during the remainder of the process’19 (p.2). Initially we invited LLa to reflect on her experience of using Care Opinion Scotland and suggest important topics to look out for. We then shared two transcripts with her and invited further reflection on the content and how it compared with topics she had previously identified. ZS then refined and applied the coding framework to all transcripts. Co-investigator GA also read two transcripts and took part in a Skype meeting with Lla and the two researchers (ZS and LLo) to debate the emerging analysis. Throughout this process, LLa drew our attention to issues of unequal power and vulnerability.

Findings

Our findings are presented in two main sections: a summary of the analysis of staff replies to Care Opinion stories, followed by a more in-depth analysis centred around the theme of anonymity, focusing on:

Understanding anonymity;

Breaking anonymity and diversion into offline communication;

Veracity and vexatiousness;

Who is anonymous? The case of ‘our regular person’.

Analysis of posts

Seventy-seven stories were published. From our own interpretations of both content and tone, these were classified as either positive (n=55, 71.4%), negative (n=11, 14.3%) or mixed (n=11, 14.3%). All received a response. Sixty-six per cent (n=51/77) of stories received a first response within three days, while 83% (n=64/77) received a response within seven days. There were 96 responses in total, from 20 staff members. Table 1 illustrates the spread of responders by job role.

Table 1.

Spread of responders by job role.

| Responder role/title | No. of responders | % response contribution |

|---|---|---|

| Nurse Manager | 8 | 26.04 |

| Senior Charge Nurse | 1 | 1.04 |

| Chief Nurse, Medicine | 1 | 19.79 |

| Interim Chief Nurse, Surgery | 1 | 13.54 |

| Deputy Service Manager | 2 | 13.54 |

| Patient Experience Manager | 1 | 4.17 |

| Patient Experience Officer | 1 | 1.04 |

| Patient Affairs Manager | 1 | 5.21 |

| Clinical Quality Facilitator | 1 | 7.29 |

| Service Support Manager | 1 | 3.13 |

| Head of Service | 1 | 2.08 |

| Divisional General Manager | 1 | 3.13 |

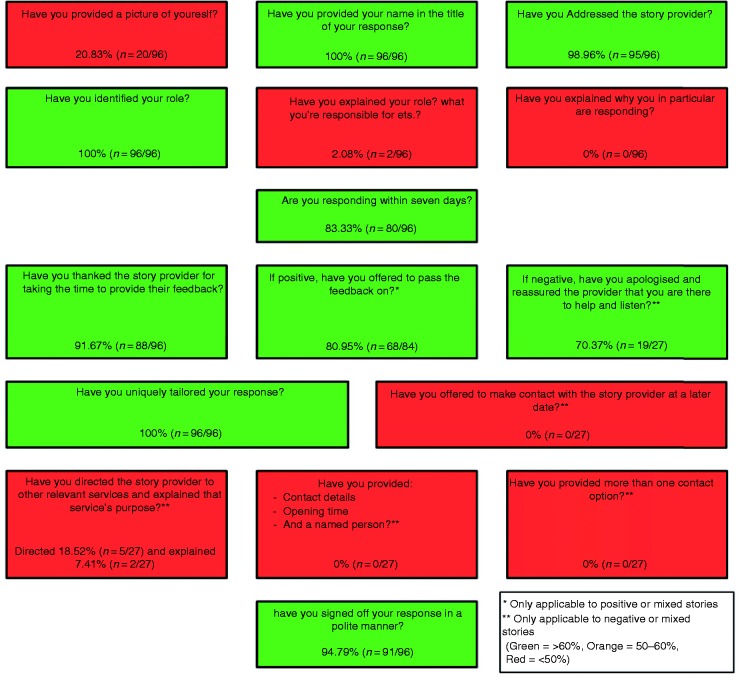

We used framework analysis to summarise how each response performed against the ‘LLRF’ criteria17 (see Figure 1). Boxes marked in red suggest areas for possible improvement, though it is worth noting that signposting people to other services, with contact details, may not always be appropriate.

Figure 1.

Performance against the ‘LLRF’ criteria.

While some offered other contact details as well as responding to the content then and there, there were very few examples where diversion into offline communication was presented as the only avenue. The response below was a striking exception:

Without your details we cannot comment on your particular case … We are sorry, but cannot comment on why your fracture was not identified … If you would like to take this further please feel free to contact me direct at the Feedback Service [= complaints].

Interview findings

Findings are presented below in four thematic sections:

Appreciating the value of anonymity;

Breaking anonymity and diversion into offline communication;

Veracity and vexatiousness;

Who is anonymous? The case of ‘our regular person’.

Appreciating the value of anonymity

There was a common theme of staff feeling somewhat exposed and anxious about what to say, and how to say it, particularly when staff were new to responding and despite some initial training.

I struggled a little bit thinking whatever I write is going out to the world … I had one glitch in the beginning where I had put like an exclamation mark at the end of my sentence and the chap came back critical of that. (04)

Nevertheless, it is important to emphasise that, despite some of the more ambivalent responses explored in subsequent sections, participants generally empathised with and understood why users valued the anonymity and distance afforded by Care Opinion. For example:

I think maybe a lot of patients still think that if I say something while I’m a patient in the ward to a nurse, they would get sub-standard care and treatment, or they’d be seen as trouble again. (07)

[Anonymity] doesn’t concern me … No matter how much reassurance we try to give to people that their care will not be adversely affected by them making a complaint, people, we know, are still fearful, particularly people with long-term conditions or that know that they’re coming back into the system. They want to get their views across, but they don’t want to be named or singled out. (05)

One participant recognised that offering a variety of ways to feed back was useful, especially for those who might be put off by formal processes.

Anonymity was usually understood to be about protecting people’s identity from healthcare staff, as opposed to privacy on a public platform more generally (for example ensuring family members or friends could not identify a story author). Participants often referred to the courage, time and effort it took for people to get as far as posting on Care Opinion. One exception to this was a member of staff who implied posting on Care Opinion might be a fleeting or casual act, and that this might explain why people did not respond when asked if they would like to identify themselves and pursue the issue offline.

When there’s been criticism or if you wanted more around the story you would say, ‘Can you contact me? This is my contact information. You can email me, you can phone me.’ But often people don’t want to do that, that’s been my experience. Even when they’ve been critical and you give them that and you can say, ‘This is really important. If that’s how you felt then we need to look at that. Can you contact me?’ and they don’t, so … I think it’s because it’s such an accessible media for them to do it, they can just do it and they’ve moved on, whereas I’m here going, ‘Actually, tell me more about that, I want to know when that happened’, or I’d like to engage with them about that. But they don’t, and that’s their choice and that’s fine. (03)

Whilst respecting their right to anonymity, there is a perhaps surprising assumption here that the issue might not have been that important to the person posting, whereas the member of staff is left feeling anxious and wanting further resolution. This asymmetry of perspective on who is most affected is discussed further under ‘Veracity and vexatiousness’.

However, one member of staff shed a very different light on unwillingness to self-identify in talking about their own experience of posting on Care Opinion as a patient:

When I first started using it, I posted a story … The best way to find out how it works is to post a story of your own. So, I did that, and the person who responded said, ‘Please get in touch’ and I thought, ‘No, I don’t want you to know it was me that posted that story’. I’d like to see that they had done something from all the information that I had given them. I doubt anything was, because I didn’t take that next step … Sometimes it’s the only way to get more information, and to get to the bottom of the story. I think for some people as well, that they do want to have that face-to-face meeting, and I think face-to-face is often really important, but I also think that we need to recognise there are changes we can make without it being face-to-face … There’s generic stuff to be learned. (06)

Another member of staff described their hesitation about posting their own story:

I’m a senior person in this organisation and things didn’t always go the way I wanted them to. Did I put my story on Care Opinion? No, I didn’t, because – I don’t know why really. All those feelings of it’s difficult to do, it takes you a long time to get your head in the right place … If it’s a struggle for me, it just goes to show what a struggle it is for most people. And, again, there is often quite a time lapse for people before they can. (05)

This member of staff went on to note that ‘there isn’t really any equivalent thing for staff to share their experiences in an anonymous way’ and that this might be useful.

Where participants talked about lack of understanding for anonymity, it was often through sub-narratives critical of the way other colleagues or other organisations responded, or blaming past approaches to responding which would now no longer be acceptable.

We’d had a story for a [General Practitioner] practice, where a lady had gone in to get a smear test, I think it was, and she’d also said that she was interested in stopping smoking, and the practice nurse had basically said, ‘That’s nothing to do with me’ and I think had been quite abrupt and rude throughout that appointment, so the lady had gone onto Care Opinion to say that, and we’d then gone back to the practice and said what had happened. And they said, as they usually do, ‘We need to know who that was. We can’t do anything unless you tell us which patient it is’. We said that that’s not really how it works, we’d like to think you’d make a change for all your patients, not one individual. (06)

These stories are thus positioned as a contrast to participants’ own reportedly more understanding position, distancing themselves from less empathetic responses.

Breaking anonymity and diversion into offline communication

A common response on Care Opinion includes staff inviting people to identify themselves offline to continue the discussion (the ‘offline response’ category identified by Ramsey et al.18). Various positive reasons for doing so were identified. These included wanting to ensure that positive comments and thanks are directed to the individual or team responsible, or to expedite care:

I managed to contact someone in the service to speak to them about this lady and they managed to get an appointment, and then she was incredibly grateful that somebody had listened to her and had managed to resolve something. (05)

Several staff expressed a preference for face-to-face or telephone communication as a way to resolve issues more quickly or to make contact feel more personal and responsive, whether the feedback was negative or positive.

Sometimes it’s the only way to get more information, and to get to the bottom of the story. I think for some people as well, that they do want to have that face-to-face meeting, and I think face-to-face is often really important, but I also think that we need to recognise there are changes we can make without it being face-to-face. (06)

You’re always going to get somebody that’s not happy with something, but if you’re dealing with it at the bedside, it shouldn’t come to that [online feedback] … if you’re face-to-face with your patient, there’s nothing better than hearing your patient saying, ‘You’ve done a fabulous job, thank you very much’, or, ‘I buzzed you but you took 45 minutes’, you can then say, ‘I am so sorry I took 45 minutes, there’s no excuse, I was with another patient but that’s no excuse, I could have got somebody else to come and do it.’ So you’ve responded there and then, they think, ‘She’s taken on-board that she took 45 minutes and I appreciate that and I hadn’t realised there was a sick patient next door.’ (08)

I guess the only problem I have with Care Opinion as well, you don’t often know when things have happened. With a complaint we usually have obviously the details of the person complaining, when the thing happened, or where it happened. If they use the Care Opinion we know where, but often you don’t know when it’s actually happened. I know staff can sometimes figure it out but then you think that’s the whole point of Care Opinion, that they want to raise it about people having it against their name, if they were dissatisfied about their care, staff knowing they weren’t satisfied with their care. Yeah, I think, yeah, there’s a mixture of things in there. (09)

However, this presupposes that wanting an issue ‘resolved’ is the reason why someone has posted, and that identifiable communication is what people are really seeking – as participant 06 above recognised, this may not always be appropriate. Our Patient Public Involvement partner emphasised to us the importance of interrogating whose interests and convenience are best served by breaking anonymity.

For example, a participant who at one level regarded anonymity as ‘fair enough, it’s the digital age’ also commented:

Participant: Twice I’ve asked someone to contact me they’ve relayed some issues and I’ve asked them to contact me and left them my number so that we can discuss it further, but they never contacted me. So, I then park that there because I probably need a bit more information.

Interviewer: What would make you think about taking it offline and asking them to contact you?

Participant: I guess it’s because I’m responding to them but I’ve no other way of contacting them. Other than writing that response, there’s no way of contacting them. You don’t really know if they’ve read it, do you? … There’s no way of knowing if you’ve helped them or not. (10)

As with participant 03 earlier, this implies more a staff need to know than what is most helpful to the patient.

Another participant who was keen on ‘just picking up the phone … instead of this tennis volley of emails, and correspondence’ reflected on wider experience of dealing with feedback cards, and how telephoning may not have been the right approach with one young woman:

I do remember phoning somebody back, but that was a feedback card … I phoned her back and said, is it okay to talk to you? She said yes, and all of a sudden, the phone went dead. I thought it was maybe me, so I phoned her back, but the phone rang, and rang, and rang, and I thought clearly this person doesn’t want to – I thought just leave it at that. It’s interesting some of the responses. Obviously that person wasn’t in the frame of mind. I came away with that conclusion that they weren’t in that frame of mind to speak about whatever they wanted to speak about. (07)

It is important to note that our analysis of staff’s actual responses showed that mostly staff did engage positively with the information in front of them.

They didn’t want to phone, they wanted to raise it through Care Opinion. We should just respect their mechanism for raising feedback to us, and I think it does feel a bit of a cop out to say, ‘Please give me a call’. I think it’s good that we say … like you say, tackle it as much as we can but say we would really value having an opportunity to hear more about your experience and if you want to, then … but I think that should just be an additional thing to tackling it … People don’t want to be signposted, they want to be acknowledged and heard, and get a human response. (09)

One participant argued that the offer of further contact was what mattered, not whether it was taken up.

Sometimes the fact you’re willing to meet with them, they don’t always take you up on that. I think the fact that you’ve taken them seriously, you’ve acknowledged that the care hasn’t been as you would have expected it to be and that you are on their behalf going to act on that. Sometimes that’s enough. (02)

Veracity and vexatiousness

Implicit or explicit in some comments was the perception that anonymity made stories less credible or trustworthy. This was by no means universal; as participant 05 said, ‘I don’t think for one minute that people make up stories.’ Others commented that it was not so much that they did not believe a certain piece of feedback, but that being able to talk to someone reinforced or elaborated on the story, and they contrasted online responding to Care Opinion with letters and complaints:

It’s so much better to just pick up the phone because you can hear it properly. (07)

At the feedback services, we are very much now trying to pick up the phone rather than getting a dry letter apologising … just to pick up the phone and actually say to the family or the patient themselves, ‘I've received your letter, can you talk me though it?’ and often what's on the letter is not really the problem. Once you start speaking to them you find out that actually, it’s something else that they’ve got an issue with. (04)

Yet even in these more positive statements there is an implication that the written word might not be the full story or the real issue. The inability to ‘verify’ details, to investigate what had ‘happened’, made some staff feel very uncomfortable. One interview included a lengthy narrative about a complaint made on Care Opinion and subsequently de-anonymised, about a dying relative’s care and poor communication, which the participant felt was unfair and inaccurate, but there was ‘no redress’.

What she was saying, I didn’t recognise as my in-patient ward because I know that’s not the quality of care that they deliver. The things she was saying just didn’t feel right – obviously that’s what she felt. I put in a response and I sought support from Care Opinion, and I put a response to say that I was really saddened to read of her experience and she’s raised a number of points that we would like to look into further, and we would like to meet with her … She was very limited around her availability to meet us because she worked. She gave us one day … We all cancelled what we were doing … and then the day beforehand she just said that we hadn’t got back to her with enough time so she had decided to go back to work. Then another date was set … She never came. Then she wrote on Care Opinion, basically, that she got no support from [the hospital], that she tried to meet up with us and we had failed … She’s anonymous on Care Opinion. She can say these very negative things, you know? … That’s out there in public. I don’t really care so much for myself wasting the time; I do care for the staff who have been involved in delivering very good care to him. And I care for the public that somebody who might be facing a diagnosis, as to what her negative feedback – her untruths, actually, what that communicates to them. But there’s no redress because she’s anonymous … You can say anything. You can say anything you like. (01)

The participant expresses concern for the reputation of both clinical colleagues and the organisation, and how this may affect other patients reading Care Opinion, as well as a sense of unfairness.

The public visibility of both posts and staff responses, coupled with anonymity and potential ‘untruths’ creates a particular sense of vulnerability.

There were also some concerns about senior staff responses seeming too ready to endorse the patient’s view without question and feeling for colleagues on the receiving end:

A couple that I did read I did think we’ve gone slightly too far with the empathy on that … I would have been furious if that had been me. (09)

My initial thought was, ‘Oh my goodness, why not just kick a team when it’s down?’ The team’s already struggling, it’s needing more resources, it’s needing support. (01)

By contrast, participant 02 argued that ‘truth’ was not the issue so much as feeling.

There’s often two sides to every story, however you’ve got to respond to the patient because it’s how it made them feel and maybe staff aren’t aware of how their behaviour is interpreted by patients. Because they’re very vulnerable and their guard is down when in the hospital. (02)

Some narratives which hinted at concerns about veracity again used distancing mechanisms that placed such attitudes in the past or in the minds of others, not the respondent.

And it was really quite difficult in the beginning because people didn’t really understand it … Often, you would get a response, ‘Well, just send it to the feedback team’ or, ‘Tell them to go through feedback’ or, ‘We can’t do anything with this because it’s anonymous’, ‘I refuse to answer this because it’s anonymous and how do I know whether what the person said is right or wrong or whatever?’ (05)

There used to be this funny thing where people used to think if a complaint was anonymous it wasn’t a real complaint. No! It’s just they don’t want you to know who they are, but they still want you to know what didn’t work. (09)

An alternative perspective was that, whilst a criticism on Care Opinion might be ‘valid’, it would be better routed through formal feedback mechanisms – perhaps unintentionally minimising the validity of other comments and responses on Care Opinion.

I think they’re both equally good [Care Opinion and formal feedback mechanism]. Maybe something I should say though, is if it is something that is a very valid complaint then we would recommend that they also fed it back through the feedback service to go through that formal structure to ensure that it was addressed correctly. (02)

Who is anonymous? The case of ‘our regular person’

It was striking that across several interviews there was a recurring narrative about one particular person – referred to by participant 03 as ‘our regular person’ – who posted frequently, sometimes with praise but often with critical feedback. Staff described finding the unpredictability and frequency of posting difficult to know how to respond to. Significantly, everyone felt they knew who this person was.

We have an individual that uses a service regularly … I’m aware who this person is. We were aware of this person before Care Opinion, because we had to use the other service that was Feedback. They found this avenue also, and it’s part of how they are. What we did with the Feedback service was develop a standard response … It’s more difficult with Care Opinion, because I know it’s anonymous, but it’s the same username so you know it’s the same individual, and they know you know who they are, so they’re speaking to you … That has been slightly more difficult. You can’t have a standard response. (03)

Despite the comment that on Care Opinion ‘you can’t have a standard response’, it was indicated in several narratives that staff were consulting each other about how to respond and developing a consistent message to close down conversation.

We’ve got one where the same person keeps putting a Care Opinion on and actually there are other issues relating to this individual, so we put quite a bland response every time and that person uses the same name every time. It is very much, ‘Thank you very much for your feedback’ full stop because there are ongoing challenges elsewhere around this individual, so that’s one that we look out for, that is a regular person that posts. It may be, some people might use different names every time they put a Care Opinion up, who knows? (04)

You don’t want tit-for-tat conversation in the public domain. (02)

In this instance it is clear that the individual had been de-anonymised, and had developed a reputation as troublesome. There were other reported instances where staff could work out from circumstantial details who a comment was from without explicitly de-anonymising the individual. Despite careful moderation and advice for site users on anonymising usernames, it was thus clear that the equalising relationship between staff and patients fostered by anonymity could be subverted.

As noted above, sometimes staff asked for a person’s identity to expedite their care. One participant reflected critically on their own practice in fixing a speedy appointment for someone and whether this was equitable.

This girl had been waiting for a procedure and she was getting married quite soon … I managed to get things sorted out there and then … I was also conscious that I didn’t want her to leap the waiting list, either … It is those that shouts the loudest, isn’t it? (07)

It is debatable whether in this case it is just a matter of ‘those that shout the loudest’ or also those who are easier for staff to empathise with. Participant 07 noted their own less positive response to another individual and having to work hard to listen with empathy.

I mean complaints and the psychology around them are quite interesting as well. I’m dealing with someone who’s got probably ment- he has got mental health issues, but I don’t know, I’m only hearing anecdotally and it’s probably right, I haven’t delved into his medical notes because it’s not for me to do that. But he’s making some unrealistic demands as well on being seen and he’s got an eye condition and everything should be big print, and although you think, ‘Well they probably should be, but it’s not practical to have everything his way’, and sometimes it’s trying to, it’s trying to listen. (07)

Discussion

Staff in our sample were generally very positive about Care Opinion as one of several ways for people to choose to give feedback. While they often said they would welcome more training in how to respond effectively and overcome their anxieties, they clearly understood why anonymity might be important for users of Care Opinion; reflected critically on their own practice and attitudes; and accepted that their own feelings of vulnerability were to some extent just an inevitable feature of the platform.

At the same time, our analysis suggests that for staff used to engaging very directly with patients and families, both clinically and in dealing with feedback, anonymous feedback creates an unfamiliar and uncomfortable situation. They are encouraged to name themselves and engage in tailored, personalised conversation, but with a faceless, nameless other. Even in more positive or straightforward encounters, their urge may be to re-personalise the conversation, and perhaps avoid the potential risk of miscommunication in writing. Wanting to ‘pick up the phone’, invite people to come and talk, and generally ‘make things better’ was a common theme, consistent with their professional values of care. In spite of themselves, they may try to work out who someone is.

Again, it is important to note that most participants acknowledged there was still useful information for improvement in anonymised comments. However, this requires a shift from the particular to the general; from an understandable impulse to want to fix a tangible problem for one ‘real’ person, to the challenge of identifying and addressing wider organisational quality issues.

At times the perceived unequal relationship and feeling of vulnerability can spark more problematic responses and feelings. Staff may see anonymity variously as a risk; a challenge to veracity; and a reason for inaction. They may feel helpless, frustrated, unfairly attacked, and that their professionalism has been impugned with ‘no redress’. The issues raised by patients who are unwilling to unmask themselves when invited to do so may be dismissed as either untrue and vexatious, or trivial and unimportant (otherwise the person would have followed up in person). This was a snapshot in time; it would be interesting to see in a more longitudinal design whether these fears and defensive reactions reduce over time. There was some suggestion in our interviews that those who had been responding longest on behalf of the organisation were most relaxed about anonymity as they gained experience and got used to this style of communication.

Feedback on Care Opinion needs to be seen within the wider landscape of staff response to feedback of any kind, whether anonymous or not. Farrington et al.20 found that medical staff in both primary and secondary care were strongly supportive in principle of incorporating patient feedback into quality improvement work. Yet they also expressed a simultaneous view questioning the credibility of survey findings and patients’ motivations and competence in providing feedback.

Adams and colleagues’21 study of staff attitudes to complaints (from known individuals) reveals similar defensiveness. They note that staff often characterised complainants as ‘inexpert, distressed or advantage-seeking’ (p.1), described their motives for complaining ‘in ways that marginalised the content of their concerns’, and rarely used complaints for improving care.

Thus staff may be sceptical of the credibility of both aggregated anonymous data from surveys and individual stories from named people. There is perhaps, however, more potential for individual anonymous narratives to be received as personally challenging and damaging than survey data, especially when they are highly visible on a public platform and other readers may be looking for a response or remediation staff feel they cannot offer.

Paediatrician Catherine Ferguson,22 reflecting on her own emotional (and physiological) responses to critical feedback, summarises the problem:

As the receiver, there is little opportunity for engaging with the feedback: for listening, for asking questions, for follow-up. This flies in the face of what we understand from the literature about how we best learn from feedback and is also different from our typical interactions with patients, which are ideally based on an exchange of information and ideas, and a mutual accountability for outcomes. While this system gives patients a safe space to share their experiences, protected from personal risk and potential repercussions, anonymous criticism can also build mistrust, and the lack of clarity and context can leave the physician receiving the criticism confused, defensive and unsure how to proceed.

Over time, Ferguson notes that she has learnt ‘to look at whatever feedback I’m getting with curiosity and to uncover any truth that might be there’, rather than disengage from it as not credible.

The ‘anonymity paradox’ identified by Speed et al.11 is at its heart a question of unequal power, risk and vulnerability. The anonymity of story authors is not always perfectly preserved and their use of anonymity to equalise or even reverse normal power relations with staff power may sometimes create backlash rather than change. It may lead to subconscious or even conscious categorisation of story authors as either pleasant, deserving individuals who merit a sympathetic response, or awkward characters to be closed down or diverted offline. This is reminiscent of the way Maben et al.23 observed inpatient ward staff to subconsciously categorise people as ‘poppets’ or ‘parcels’. Staff used to engaging directly with patients and families, both clinically and in dealing with feedback, need support in dealing with anonymous feedback, and the uncomfortable situation of unequal power it may create.

However, staff can and do recognise the need to alter the balance of power, and reflect critically on the consequences of their responses. It is important not to lose sight of growing evidence that, far from wanting to attack the NHS, patients describe their motivations for posting online feedback primarily in terms of expressing care for the NHS and its staff, and wanting to make it the best it can be.14,15

This was a small-scale study in one site. We plan to interrogate these power relationships and motivations further through the next steps with our research, a Scotland-wide PhD study, supported by The Health improvement Studies (THIS) Institute, University of Cambridge. We plan to conduct further interviews as well as ethnographic observations with staff, patients and families and policy-makers, and the studentship will incorporate a period of embedded participant observation of the moderation process at Care Opinion Scotland. Recommendations from our current findings will inform local practice, in particular through discussion and training with staff groups.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to staff participants for sharing their experiences generously and candidly. We are also grateful to James Munro, Director of Care Opinion, for reflections on an earlier draft and for facilitating conference and seminar discussions with a range of authors cited in this study who are working on online feedback generally and Care Opinion specifically.

Conflict of interest

GA is Director of Care Opinion Scotland. CH is Acting Director of Nursing and Midwifery, NHS Grampian.

Contributorship

LLo, ZS, GA and CH designed the overall study methods, and LLa contributed to designing the interview topic guide as a patient adviser. ZS and LLo obtained ethical approval. JS conducted the analysis of Care Opinion posts as a visiting medical student under supervision from ZS and LLo. ZS and CH were responsible for recruitment of interviewees. ZS led interview data collection with some input from LLo. ZS and LLo led the analysis of interviews, in which GA and LLa were also closely involved, reading and discussing a subset of transcripts, advising on coding and reflecting on emerging themes. LLo wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the University of Aberdeen College Ethics Review Board [CERB/2018/7/1641].

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by NHS Grampian Endowments Fund (grant number 2018UA012).

Guarantor

LLo

ORCID iD

Peer review

Lauren Ramsey, University of Leeds and Rebecca Baines have reviewed this manuscript.

References

- 1.Duschinsky R, Paddison C. ‘‘ The final arbiter of everything’’: A genealogy of concern with patient experience in Britain. Soc Theory Health 2017; 16: 94–110. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meterko M, Wright S, Lin Het al. Mortality among patients with acute myocardial infarction: The influences of patient-centered care and evidence-based medicine. Health Serv Res 2010; 45: 1188–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jha AK, Orav EJ, Zheng Jet al. Patients’ perception of hospital care in the United States. N Engl J Med 2008; 359: 1921–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murff HJ, France DJ, Blackford Jet al. Relationship between patient complaints and surgical complications. Qual Saf Health Care 2006; 15: 13–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edgcumbe DP. Patients’ perceptions of hospital cleanliness are correlated with rates of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia. J Hosp Infect 2009; 71: 99–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Charmel PA, Frampton SB. Building the business case for patient-centered care. Healthc Financ Manage 2008; 62: 80–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nagraj S, Abel G, Paddison Cet al. Changing practice as a quality indicator for primary care. BMC Fam Pract 2013; 14: 89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dudhwala F, Boylan A-M, Williams Vet al. What counts as online patient feedback, and for whom? Digit Health 2017; 3: 1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin G, McKee L, Dixon-Woods M. Beyond metrics? Utilizing ‘soft intelligence’ for healthcare quality and safety. Soc Sci Med 2015; 142: 19–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Griffiths A, Leaver MP. Wisdom of patients: Predicting the quality of care using aggregated patient feedback. BMJ Qual Saf 2018; 27: 110–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Speed E, Davison C, Gunnell C. The anonymity paradox in patient engagement: Reputation, risk and web-based public feedback. Med Humanit 2016; 42: 135–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alexander G. Care Opinion in Scotland: The journey so far Stirling: Care Opinion, 2018.

- 13.Powell J, Atherton H, Williams Vet al. Online patient feedback: A multimethod study to understand how to Improve NHS Quality Using Internet Ratings and Experiences (INQUIRE). Health Serv Deliv Res 2019. (in press). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Velthoven MH, Atherton H, Powell J. A cross sectional survey of the UK public to understand use of online ratings and reviews of health services. Patient Educ Couns 2018; 101: 1690–1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mazanderani F, Kirkpatrick S, Ziebland Set al. Caring for care: Rethinking online feedback in the context of public healthcare services (under review). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Ziewitz M. Experience in action: Moderating care in web-based patient feedback. Soc Sci Med 2017; 175: 99–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baines R, Donovan J, Regan de Bere Set al. Responding effectively to adult mental health Patient feedback in an online environment: A coproduced framework. Health Expect 2018; 21: 887–898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramsey LP, Sheard L, Lawton Ret al. How do healthcare staff respond to patient experience feedback online? A typology of responses published on Care Opinion. Patient Exp J 2019; 6: 9. Doi:10.35680/2372-0247.1363. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Locock L, Kirkpatrick S, Brading Let al. Involving service users in the qualitative analysis of patient narratives to support healthcare quality improvement. Res Involve Engage 2019; 5: 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farrington C, Burt J, Boiko Oet al. Doctors’ engagements with patient experience surveys in primary and secondary care: A qualitative study. Health Expect 2016; 20: 385–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adams M, Maben J, Robert G. ‘It’s sometimes hard to tell what patients are playing at’: How healthcare professionals make sense of why patients and families complain about care. Health 2018; 22: 603–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferguson C. Patient experience surveys: Reflections on rating a sacred trust. BMJ Qual Saf 2019; 28: 843–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maben J, Adams M, Peccei Ret al. ‘Poppets and parcels’: The links between staff experience of work and acutely ill older peoples’ experience of hospital care. Int J Older People Nurs 2012; 7: 83–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]