Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disease that causes cognitive and behavioral deterioration in the elderly. Neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) are one of the pathological hallmarks of AD that has been shown to correlate positively with the severity of dementia in the neocortex of AD patients. In an attempt to characterize an in vivo AD tauopathy model, okadaic acid (OA), a protein phosphatase inhibitor, was microinfused into the right lateral dorsal hippocampus area of ovariectomized adult rat. Cognitive deficiency was seen in OA-treated rats without a change in motor function. Both silver staining and immunohistochemistry staining revealed that OA treatment induces NFTs-like conformational changes in both the cortex and hippocampus. Phosphorylated tau as well as cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (cdk5) and its coactivator, p25, were significantly increased in these regions of the brain. Oxidative stress was also increased with OA treatment as measured by protein carbonylation and lipid peroxidation. These data suggest that the unilateral microinfusion of OA into the dorsal hippocampus causes cognitive deficiency, NFTs-like pathological changes, and oxidative stress as seen in AD pathology via tau hyperphosphorylation caused by inhibition of protein phosphatases.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Tauopathy, Cognitive deficiency, Tau phosphorylation, Neurofibrillary tangles, Oxidative stress

1. Introduction

Neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), a major hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), are highly prevalent in the aging hippocampus of AD patients (Lace et al., 2009). Tau proteins are a group of microtubule-associated proteins that are abundant in neurons and play a key role in microtubules stabilization, axonal transportation, and neurite outgrowth under physiological conditions (Avila et al., 2004; Devred et al., 2004; Johnson and Stoothoff, 2004; Weingarten et al., 1975). On the other hand, deposits of abnormally hyperphosphorylated tau protein are found in many neurodegenerative diseases such as AD (Avila et al., 2004; Grundke-Iqbal et al., 1986a,b; Johnson and Stoothoff, 2004; Lace et al., 2009).

Clinical studies have suggested that the severity of dementia in AD patients is positively correlated with the numbers of NFTs in the cortex (Arriagada et al., 1992; Nagy et al., 1995). The tau hypothesis, which proposes that tau protein abnormalities initiate the AD cascade, is also supported by the observation that NFTs are found in the neurons and their aggregates disrupt the neuron’s transport system ultimately resulting in neuronal death (Brandt et al., 2005; Hernandez and Avila, 2007; Lovestone and Reynolds, 1997; Mudher and Lovestone, 2002). Although the tau hypothesis is supported by many experimental studies, especially studies from transgenic mice (Duff and Planel, 2005; Santacruz et al., 2005), it remains unclear whether NFTs are the initiating factors or merely markers of the disease process and whether NFTs crosstalk with other AD-related hallmarks (Castellani et al., 2008).

Several protein kinases, including glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3), mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), and cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (cdk5), have been reported to phosphorylate tau protein at various sites that are found in AD hyperphosphorylated tau (Correas et al., 1992; Drewes et al., 1992; Hanger et al., 1992; Liu et al., 2008; Lucas et al., 2001), whereas its dephosphorylation is mainly catalyzed by protein phosphatase (PP) 1, 2A, 2B and 5, with PP2A as the major player (Arendt et al., 1998b; Gong et al., 1994a,b,c; Liu et al., 2005). An imbalance between tau phosphorylation and dephosphorylation is critical to AD tauopathy (Arendt et al., 1998a; Gong et al., 2006). Selective inhibition of PP 2A by okadaic acid (OA) can induce an Alzheimer-like hyperphosphorylation and accumulation of tau both in vivo (Arendt et al., 1998a; Gong et al., 2006) and in vitro (Alvarez-de-la-Rosa et al., 2005; Zhang and Simpkins, 2010).

It is well established that the prevalence and incidence of AD in women dramatically increases following post-menopause (Filley, 1997) and that estrogens are potent neuroprotectants (Singh et al., 2006). Herein, we developed an experimental tau model via chronic microinfusion of OA, a serine/threonine phosphatase inhibitor, into the dorsal hippocampus of ovariectomized adult Sprague–Dawley (SD) rat, which would mimic the estrogen deficiency of the postmenopausal state. Chronic infusion of OA induced a progressive cognitive deficiency, NFTs-like conformational changes in the brain, and oxidative damage in both the cortex and hippocampus. Inhibition of serine/threonine phosphatases also increased phosphorylation of tau and protein expression of cdk5 and p25. Our findings suggest that chronic infusion of OA induces an in vivo tauopathy model; and cdk5 plays a role in tau hyperphosphorylation induced by the inhibition of protein phosphatases.

2. Results

2.1. Effect of OA infusion on behavioral performance

To examine the effect of serine/threonine phosphatase inhibition on NFTs in the hippocampus of ovariectomized adult rat, which would theoretically mimic the postmenopausal condition in the human female, OA was unilaterally microinfused into the right dorsal hippocampal area via an osmotic pump. Rats were separated into three groups: vehicle control, low-dose OA, and high-dose OA. Following a 14-day infusion period, each rat was subjected to a spatial learning and memory test using the Morris water swim maze and a motor function test using the rotarod.

2.1.1. Body weight

The body weight of each rat was monitored daily throughout the treatment period and during the behavioral testing period (data not shown). As expected, each rat exhibited a steady increase in body weight and no rats died during the experimental period. There were no effects of OA infusion on the rate of weight gain or on the absolute body weight among the different groups. These data suggest that microinfusion of OA into unilateral dorsal hippocampus did not exert a generalized toxicity.

2.1.2. Spatial learning and memory

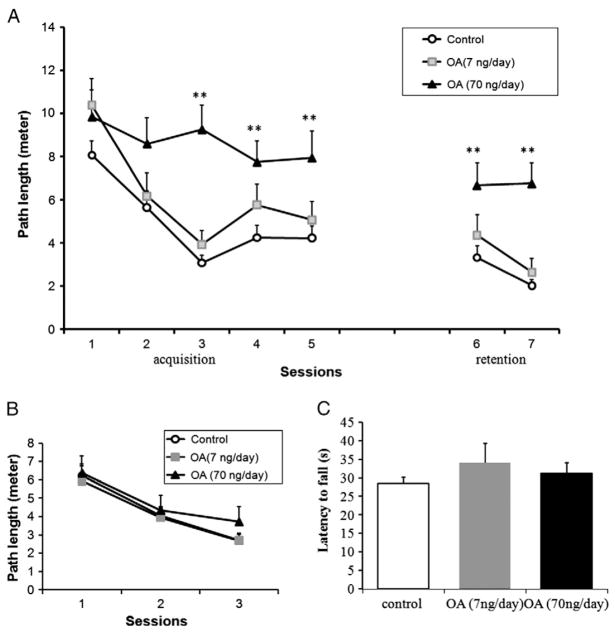

During the first three training sessions of acquisition (sessions 1–5), rats from the control group and the low-dose group learned to locate the hidden platform efficiently as evidenced by decrease in path length over sessions (Fig. 1A). In contrast, the high-dose group showed little improvement in behavior over the 5 sessions (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

MWM performance of rats infused with OA for 14 days. (A) The behavior test in the MWM started after 14 days of microinfusion of OA or vehicle into the dorsal hippocampus of the rats. The swimming path length to the escape platform was recorded to assess learning ability (acquisition test) and memory ability (retention test). After regular MWM, a visible MWM test (B) was performed and followed by rotarod tests (C). Control: 1% DMSO in artificial spinal–cerebral fluid, n=20. Treatment groups: OA (7 or 70 ng/day) was microinfused into unilateral dorsal hippocampal area for 14 days, n=10/group. Data were represented in mean±SEM. **p<0.01 between control and OA (70 ng/day) groups.

The retention sessions (sessions 6 and 7) were started 2 days after the acquisition training. In the control group and low-dose OA group, the rats swam the same and even shorter distances to find the platform as in acquisition sessions, but there are no significant changes in the high-dose OA group (Fig. 1A).

2.1.3. Visible MWM

After regular MWM tests, the rats were retested in the Morris water maze with a visible platform. This test permits the assessment of motivational and/or sensorimotor factors rather than spatial learning per se. The rats from all three treatment groups learned the path to the platform with the training. There were no differences in the ability of the different treatment groups to locate the visible escape platform in any single session (Fig. 1B).

2.1.4. Rotarod

To rule out group differences in motor coordination, all the rats were subjected to rotarod tests. Learning of coordinated running was measured by the latency to fall over the three training sessions and maximum performance was estimated by performance on the final session (Fig. 1C). A one-way ANOVA on latency to fall for the final session failed to indicate any effect of OA treatment on motor function.

2.2. Pathological changes in OA-induced tauopathy model in female rats

To characterize the pathological changes of our experimental AD model induced by OA in female rats, brain sections were stained with silver nitrate to assess NFT-like conformational changes and probed with antibodies against phosphorylated tau.

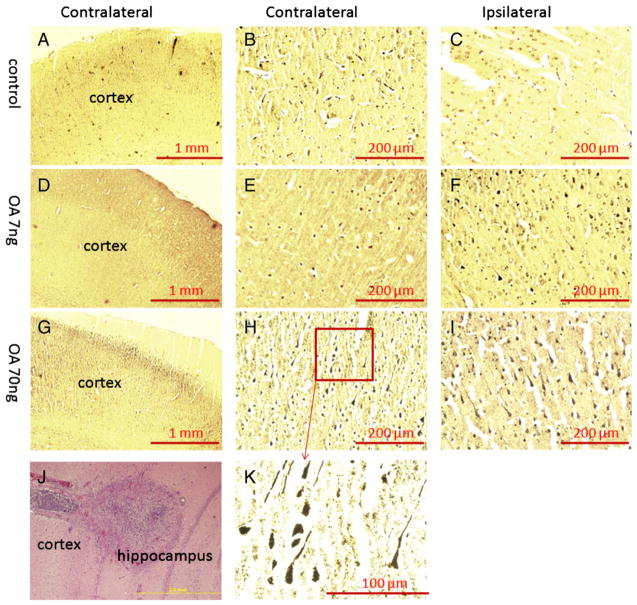

2.2.1. Silver staining of pathological changes in OA-induced tauopathy model

After this series of behavioral tests, half of the rats were submitted to prepare paraffin sections of brain samples; the other half of the rats was subjected to oxidative stress assays. After deparaffinization and rehydration, the brain sections were stained in silver nitrate solution following the Bielschowsky’s protocol. As shown in Fig. 2, there were NFTs-like conformational changes (silver positive staining) identified in the ipsilateral cortex of the low-dose treatment group and in both ipsilateral and contralateral cortices of the high-dose treatment group compared to the control group. In the hippocampus, only the ipsilateral side of the high-dose OA group showed silver positive staining of NFT-like conformational changes (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Bielschowsky silver staining of the cortex in OA-treated rats. After the behavioral tests, half of rats received transcardiac perfusion with 4% formaldehyde in PBS, followed by immersion fixation of the removed brain. Then brain tissue was processed for paraffin sectioning, and 10-μm slides were prepared for silver staining. There was no positive staining found in either contralateral (A, B) or ipsilateral (C) cortex of control group. A few silver positive staining was found in the ipsilateral side of the cortex received low-dose OA (7 ng) infusion (F) but was not seen in the contralateral cortex (D, E). Much more silver positive staining was found in the both sides of cortex in high-dose OA group (G, H, I, K). The brain infusion cannula terminal was verified by H&E staining (J).

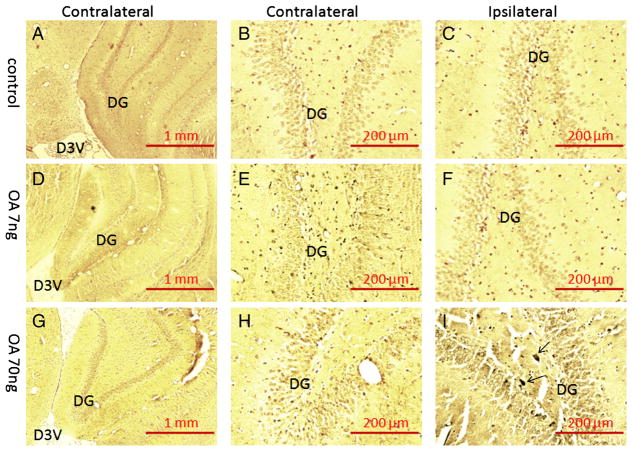

Fig. 3.

Bielschowsky silver staining of the hippocampus in OA-treated rats. There was no positive silver staining found in the hippocampus of either control group (A, B, C) or low-dose OA (7 ng) group (D, E, F). A few silver positive staining was found in the dentate gyrus area of ipsilateral hippocampus from rats that received high-dose infusion of OA (70 ng) (I) but not in the contralateral side (G, H).

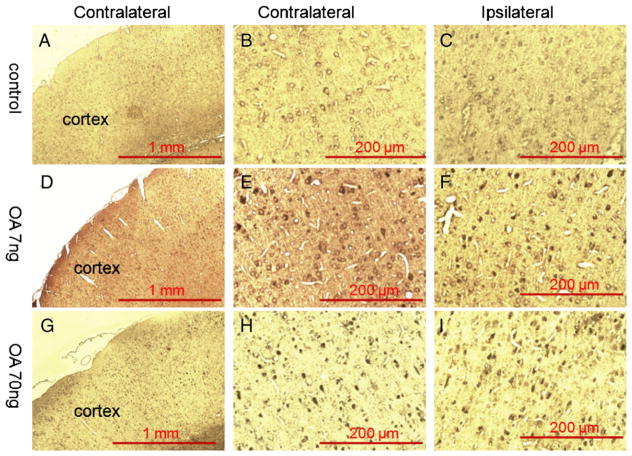

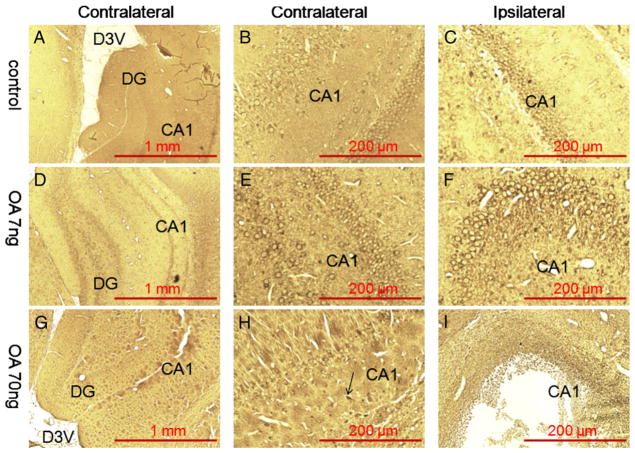

2.2.2. Immunohistochemistry of pathological changes in OA-induced tauopathy model

Both the low- and high-dose OA treatment resulted in higher immunoreactivity to p-tauThr205 in both the ipsilateral and contralateral cortices (Fig. 4). On the other hand, phosphorylated tau was only seen in ipsilateral hippocampus of the high-dose OA treatment group (Fig. 5). High-dose OA treatment induced a very large lesion in the ipsilateral dorsal hippocampal area that was not seen in low-dose OA treatment group (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Immunohistochemistry staining of the cortex in OA-treated rats. Fourteen days after microinfusion of OA into dorsal hippocampus unilaterally, rats were subjected to paraffin section preparation for immunohistochemistry staining and probed with antibody raised against phospho-tau (p-Thr205). There was no positive staining found in either side of the cortex in the control group (A, B, C). A few anti-p-Thr205 immunoreactivity positive staining was found on both side of the cortex in the rats that received low-dose OA infusion (D, E, F) and more positive staining was found in high-dose OA group (G, H, I).

Fig. 5.

Immunohistochemistry staining of the hippocampus in OA-treated rats. Fourteen days after microinfusion of OA into dorsal hippocampus unilaterally, rats were subjected to paraffin section preparation for immunohistochemistry staining and probed with antibody raised against phospho-tau (p-Thr205). There was no positive staining found in either side of the hippocampus in the control group (A, B, C) or low-dose OA (7 ng) group (D, E, F). A few anti-p-Thr205 immunoreactivity in positive stained neurons were found in the CA1 area of the contralateral hippocampus of rats that received high-dose infusion of OA (70 ng) (G, H), and the ipsilateral hippocampus CA1 area was damaged (I).

2.3. Tau phosphorylation in OA-induced tauopathy rats

There was a dose-dependent increase of p-tauThr205 in both cortex and hippocampus of OA treatment groups (Fig. 6). Low-dose OA infusion induced a four-fold increase in p-tauThr205 while high-dose OA infusion showed a six-fold increase as compared to nontreated controls in the ipsilateral side of the hippocampus (Fig. 6A). In the ipsilateral cortex, p-tauThr205 protein levels were increased over two-fold in the low-dose OA group and over three-fold in the high-dose OA group (Fig. 6B). A slight but statistically significant increase in tau phosphorylation was seen in the contralateral hippocampus and cortex of the high-dose OA group (Figs. 6A and B, respectively).

Fig. 6.

Tau phosphorylation in OA-treated rats. Fourteen days after microinfusion of OA into dorsal hippocampus unilaterally, rats were decapitated, and the brains were removed. The cortex and hippocampus were separated, homogenized in RIPA buffer, and centrifuged. The supernatants from different treatment groups were further subjected to Western blot for assessing the ratio of phospho-tau (T205) over total tau (T1) in both the hippocampus (A) and the cortex (B). Data are presented as mean±SEM for n=5. *p<0.05 and **p<0.01.

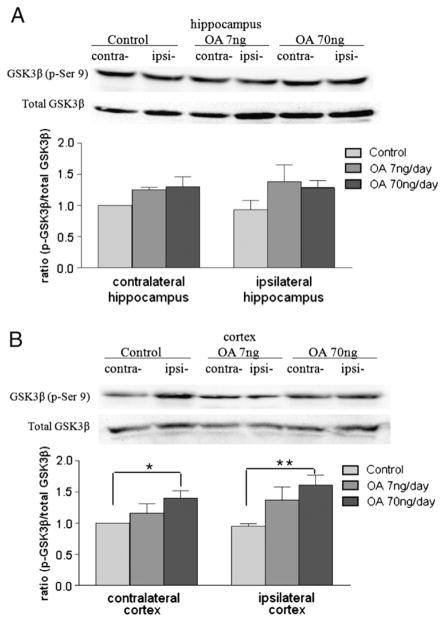

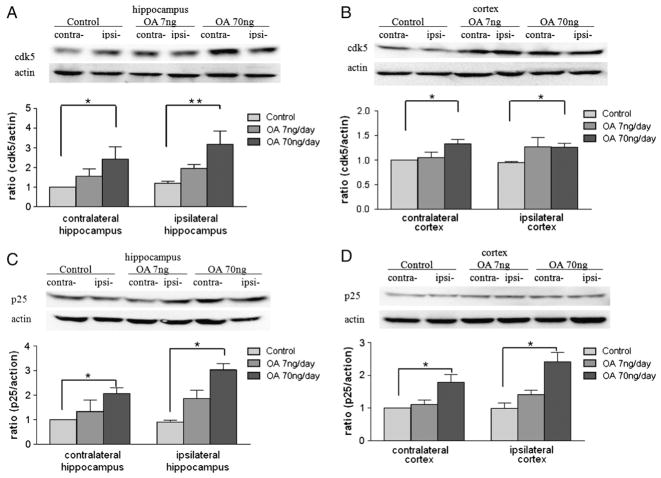

2.4. Effect of OA on tau protein phosphatases and kinases

An imbalance in the activities of tau kinases and phosphatases is crucial to tau hyperphosphorylation. To determine the players involved in the phosphorylation of tau, the protein levels of certain tau protein kinases (GSK3β, cdk5, and p-ERK1/2) and phosphatases (PP1 and PP2A) were measured in our OA- induced AD model. Samples of cortex and hippocampus were collected immediately after 14 days of microinfusion of OA into unilateral dorsal hippocampus of adult female ovariectomized SD rats. In the hippocampus, there was no significant difference in protein expression of p-GSK3 (Ser9) across the treatment groups compared to the control group (Fig. 7A); in the cortex, the high-dose OA induced an increase in p-GSK3 (Ser9) in both the ipsilateral and contralateral sides (Fig. 7B). On the other hand, protein expression of cdk5 was increased by three- and two-fold on the ipsilateral and contralateral sides of the hippocampus following high-dose OA treatment, respectively (Fig. 8A). In the cortex, the high-dose OA induced an increase in cdk5 in both the ipsilateral and contralateral sides (Fig. 8B). Meanwhile, the high-dose OA also led to an increase in levels of the cdk5 coactivation protein, p25, in both cortex and hippocampus (Figs. 8C and D). In both regions, the ipsilateral response was greater than the contralateral response (Figs. 8C and D). There were no significant changes in protein levels of phosphorylated ERK1/2 in any region of the brain with either low- or high-dose OA infusion (data not shown). Moreover, the expression of PP1 and PP2A did not show statistical significance (data not shown).

Fig. 7.

GSK3β levels in OA-treated rats. Fourteen days after microinfusion of OA into dorsal hippocampus unilaterally, rats were decapitated, and the brains were removed. The cortex and hippocampus were separated, homogenized in RIPA buffer, and centrifuged. Supernatants from different treatment groups were further subjected to Western blot for assessing the ratio of p-GSK3β (Ser 9) over total GSK3β in both the hippocampus (A) and the cortex (B). Data are presented as mean±SEM for n=5. *p<0.05 and **p<0.01.

Fig. 8.

Cdk5 and p25 levels in OA-treated rats. Fourteen days after microinfusion of OA into dorsal hippocampus unilaterally, rats were decapitated, and the brains were removed. The cortex and hippocampus were separated, homogenized in RIPA buffer, and centrifuged. Supernatants from different treatment groups were further subjected to Western blot for assessing the levels of cdk5 and p25 in both the hippocampus (A, C) and the cortex (B, D). Data were represented as mean±SEM for n=5. *p<0.05 and **p<0.01.

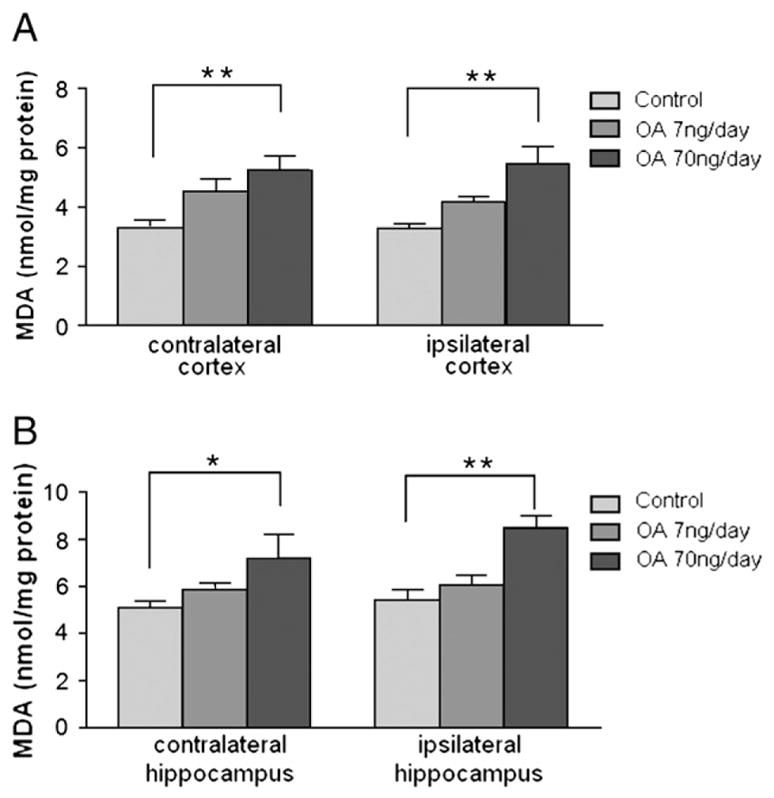

2.5. Oxidative stress induced by OA infusion

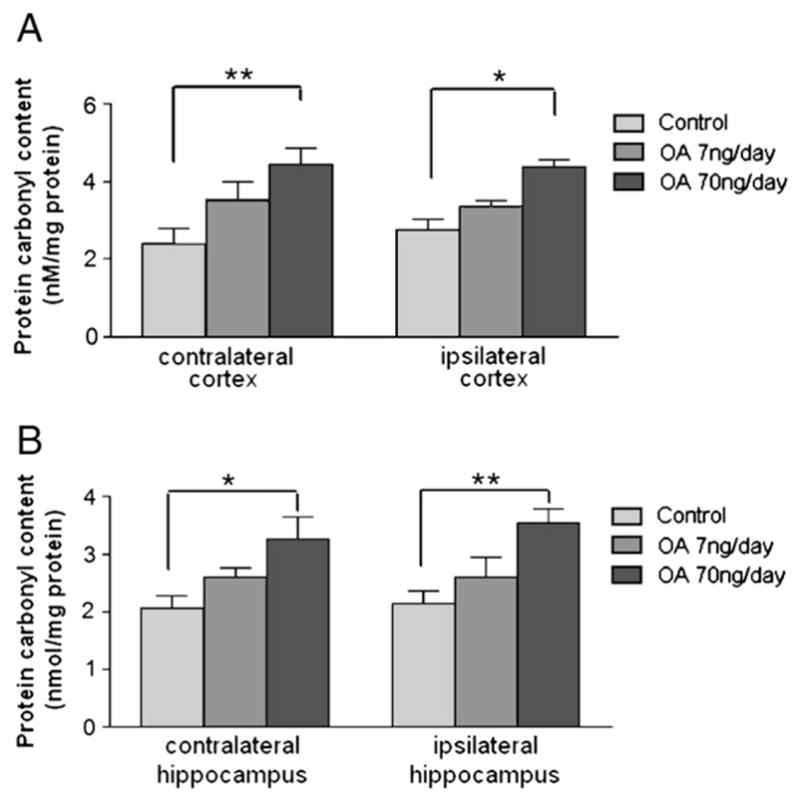

Because oxidative stress has been implicated in the pathology of neurodegenerative diseases, lipid peroxidation and protein carbonylation were determined. There was an OA dose-dependent increase of lipid peroxidation as measured by MDA content in both contralateral and ipsilateral cortex. Lipid peroxidation was significantly increased in the both cortex and hippocampus of high-dose OA group on the contralateral and ipsilateral sides (Figs. 9A and B). Although there was no statistical significance in the lipid peroxidation between low-dose OA and control groups in either sides of the hippocampus and cortex, a trend for increase was observed. Similar results were seen with protein carbonylation where the high-dose OA induced an increase in protein carbonylation in both the ipsilateral and contralateral cortices and hippocampus (Fig. 10).

Fig. 9.

MDA content in OA-treated rats. After behavioral tests, as described in Fig. 2, half of the rats were assessed for MDA concentrations. Cortex and hippocampus were separated and homogenized in specific buffer, and then the supernatants were collected for the lipid peroxidation assay as described in the Experimental procedures. Control: 1% DMSO in artificial spinal–cerebral fluid, n=4. Treatment groups: OA (7 or 70 ng/day) in vehicle, n=4/group. Data were represented in mean±SEM. *p<0.05 and **p<0.01.

Fig. 10.

Protein carbonyl content in OA-treated rats. The cortex and hippocampus tissue from different treatment groups were homogenized, and the supernatants were collected for the protein carbonyl assay as described in the Experimental procedures. Control: 1% DMSO in artificial spinal–cerebral fluid, n=4. Treatment groups: OA (7 or 70 ng/day) in vehicle, n=4/group. Data were represented in mean±SEM. *p<0.05 and **p<0.01.

3. Discussion

The present study aimed to characterize a rat model of AD tauopathy seen in postmenopausal females by chronic unilateral infusion of okadaic acid, a serine/threonine phosphatase inhibitor, into the dorsal hippocampus of ovariectomized adult SD rats. We show that chronic unilateral infusion of OA induces deficits in spatial learning and memory. These deficits in learning and memory are coupled to pathological staining of NFTs-like conformational changes as well as increased phosphorylation of tau. In addition, cdk5 appear to be players in the phosphorylation of tau in this model, while the expression of active ERK1/2, PP1, and PP2A did not change with OA infusion. We also observed increased oxidative stress. Our findings suggest that chronic infusion of OA could induce an in vivo tauopathy model and that cdk5 may be involves in OA-induced tau hyperphosphorylation.

The cognitive deficits seen in our OA infusion model of tauopathy are consistent with previous studies showing spatial memory deficits in both rats and patients with unilateral damage to the right hippocampal formation (Abrarahams et al., 1997; Bohbot et al., 1998; He et al., 2005) and the studies showing that OA infusion induced learning and memory deficiency in rats (Sun et al., 2003; Wu et al., 2008). He et al. (2005) showed that acute unilateral microinfusion of OA into the dorsal hippocampal caused spatial memory impairment in male rats, which is in accordance with our chronic infusion data. However, it is still controversial whether unilateral lesion of hippocampus, which was seen in the study of He et al. (2005) as well as in our study, is sufficient to induce learning and memory impairment. The hippocampus is known to play a major role in long-term memory and spatial navigation (Manns et al., 2003a,b) and is critical for spatial memory in rodents (Nadel, 1991). Some studies had shown that a single intact hippocampus is sufficient for executing a spatial task (Li et al., 1999), but other studies show that a unilateral hippocampal lesion led to spatial memory impairment (He et al., 2005). Certain clinical studies also reported that a cognitive decline was observed in temporal lobe epilepsy patients due to unilateral hippocampal sclerosis (Marques et al., 2007). Some research shows that spatial learning impairment is parallel to the magnitude of dorsal hippocampal lesions but not ventral lesions (Moser et al., 1993, 1995). Via chronic microinfusion of OA into the right dorsal hippocampus of ovariectomized adult female SD rats unilaterally, a significant learning and memory deficiency was observed without changes of body weight, motor coordination, and sensorimotor ability in the high-dose OA group. This suggests that unilateral dorsal hippocampal infusion of OA into ovariectomized female rats may be sufficient to induce AD-like spatial memory impairment. However, according to the “two-hit hypothesis” (Zhu et al., 2004, 2007), this spatial memory impairment may be due not only to the effect of okadaic acid but also to the deprivation of endogenous estrogen. It has been reported that estrogen is required for cognitive behaviors (Rissman et al., 2002).

But the underlying mechanism still remains elusive. We determined if neuropathological changes occurred in the contralateral side of brain after the ipsilateral damage induced by OA. We found that there was silver positive staining of NFTs-like formation and progressive formation of anti p-tau-Thr205 immunoreactivity in both the cortex and the hippocampus, especially the contralateral side of the brain, which may be responsible for the cognitive deficits due to unilateral hippocampal lesions induced by OA.

Our data showed that OA could induce a hyperphosphorylation of tau at Thr-205, which is consistent with the data from other groups (Arendt et al., 1998b; Goedert et al., 1995), and this supports our neuropathological data showing the formation of NFT-like conformational changes, an aggregation of phospho-tau, in the brains of OA-treated rats. Tau protein is a phosphoprotein whose expression and phosphorylation is well regulated (Baudier and Cole, 1987; Grundke-Iqbal et al., 1986b). PP2A is reported to be the major tau phosphatase in brain (Liu et al., 2005), whose activity is reduced in AD brain and dephosphorylation of tau can be blocked in cells by OA (Arendt et al., 1998b; Planel et al., 2001). There are 79 putative serine or threonine residues and 5 tyrosine residues located in two proline-rich regions, in the longest central nervous system (CNS) tau isoform containing 441 residues (Goedert et al., 1989; Hernandez and Avila, 2007; Johnson and Stoothoff, 2004). These sites have been divided into proline-directed and non-proline-directed groups (Morishima-Kawashima et al., 1995). Thr-205 is one of the proline-directed phosphorylation sites whose phosphorylation was associated with abnormally hyperphosphorylated tau in PHFs and tau-induced neurodegeneration (Paudel et al., 1993; Steinhilb et al., 2007). To our surprise, the significant increase of phosphorylated tau in ipsilateral hippocampus in our western data is not reflected in our pathological data which shows that there were more profound NFT-like conformational changes induced by OA observed in the cortex than in the hippocampus. This may be due to the massive hippocampal neuronal death, which was also seen in the study of He et al. (2005), showing that OA caused pyramidal cell loss in the CA1 and apoptotic cell death in the hippocampus, and therefore the loss of NFTs; and the NFT-like conformational changes found in the cortex may be due to the biochemical reaction to the damage of the hippocampus or the leakage/diffusion of okadaic acid from the brain infusion cannulae site.

To investigate the mechanism of tau phosphorylation, we assessed levels of PP1/2A and certain protein kinases, including cdk5, GSK3β, and ERK1/2, in the cortex and hippocampus of model rats. There were no significant changes of PP1/2A expression in either cortex or hippocampus after OA infusion in response to the sustained inhibition of PP1/2A activity. Although many kinases have been considered as potential tau protein kinases, so far only a few are thought to be good candidates in vivo. Two major proline-directed protein kinase families have been characterized: GSK3 and CDC2-like kinases (cdk2 and cdk5) (Billingsley and Kincaid, 1997). In our model, we found an increase of the inactive status of GSK3β by detecting the phosphorylated GSK3β at Ser 9 by inhibiting PP1/2A, which is consistent with others showing that PP2A can activate GSK3β directly by dephosphorylating Ser 9 or indirectly by dephosphorylating Akt (Lin et al., 2007). The activation of GSK3β is mediated by dephosphorylation at Ser 9 which is regulated by Akt (Grimes and Jope, 2001). Although mounting evidence supports that GSK3β, highly expressed in the brain (Woodgett, 1990) and recognized as tau protein kinase I (Ishiguro et al., 1993), is one of the kinases phosphorylating tau in vivo, GSK3β may be not the major contributor of tau phosphorylation in our model.

We also investigated another in vivo candidate for tau kinase, cdk5, which is abundant in brain tissue and has been shown to associate with tau (Tsai et al., 1994; Uchida et al., 1994). The involvement of cdk5 in tau phosphorylation is supported by our data showing that, accompanied with the tau phosphorylation, the cdk5 expression was significantly elevated in the brain of model rats; and our previous data showing that transient cerebral ischemia-induced tau hyperphosphorylation and NFT-like conformational epitopes in adult female rat cortex could be reversed by inhibition of cdks (Wen et al., 2004a,b). Cdk5 is one of the cdk family member and is activated by interaction with the non-cyclins regulatory proteins, p35 and p39 (Shelton and Johnson, 2004). A subunit of tau protein kinase II, cdk5 is associated with its activator p25 (Uchida et al., 1994). The p25 subunit, a proteolytic cleavage product of p35, accumulates in the brain and promotes the activation and mislocation of cdk5 in AD patients (Patrick et al., 1999). In vivo studies showed that p25-overexpressing transgenic mice display abnormally hyperphosphorylated tau and neurofilament, accompanied by cytoskeletal disruption (Ahlijanian et al., 2000), which is consistent with our data showing that, associated with the elevation of cdk5 expression in both cortex and hippocampus of model rats, p25 expression was significantly increased.

In our AD models, oxidative stress was also observed via measuring of protein oxidation and lipid peroxidation. The increase of protein carbonyl and MDA content in both sides of the cortex and hippocampus found in our study is consistent with the previous clinical studies (Markesbery and Carney, 1999; Pratico, 2008; Sayre et al., 1997; Smith et al., 2000). Oxidative stress is known to play an important role in AD pathogenesis. Associated with NFT and SP, a great deal of oxidative damage had been found in AD brains (Nunomura et al., 2006; Smith et al., 2000). Although the initial events of AD are still unknown, numerous studies reported an increase in oxidative stress in the AD brain as well as in cellular and animal AD models (Nunomura et al., 2006). This suggests that our model could not only mimic the cognitive impairment of AD, but also generate certain oxidative stress, which may be an important contributing factor to AD pathogenesis.

Collectively, our data showed in vivo inhibition of PP1/2A by microinfusion of OA into unilateral hippocampus could induce spatial learning and memory deficiency, oxidative stress, tau phosphorylation, and NFT-like tau pathology, and cdk5 may be involved in OA-induced tau hyperphosphorylation. Although not fully mimicking the AD pathology, our model could be a useful tool to study the tauopathy and a valuable model for preclinical testing of drug targeting on PPs.

4. Experimental procedures

4.1. Animals and chemicals

Adult female SD rats weighing between 225 and 250 g, 2 months old (Charles Rivers, Wilmington, MA, USA) were allowed to acclimate for 3 days before the onset of any procedures and were maintained at the University of North Texas Health Science Center animal facility in a temperature-controlled room (22–25 °C) with 12-hour dark–light cycles. All rats will have free access to laboratory chow and tap water. Bilateral ovariectomy was performed 2 weeks before microinfusion of OA. All animal procedures were reviewed and approved by the UNTHSC Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Okadaic acid (Calbiochem; Gibbstown, NJ, USA) was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at a concentration of 1 mM and diluted to appropriate concentration in artificial spinal–cerebral fluid. ALZET osmotic pumps (Model 1002) and brain infusion kits were purchased from DURECT Corporation (Cupertino, CA, USA). Anti-cdk5 (C-8), anti-PP1 (E-9), anti-PP2A (C-20), anti-tau (T1), and anti-p-ERK (E4) antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Anti-ERK1/2 and anti-phospho-tau (T205) antibodies were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Anti-p25, anti-p-GSK3β (Ser-9) and anti-GSK3β (27C10) antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). Immunohistochemistry ABC peroxidase staining kits and metal enhanced DAB substrate kits were purchased from Pierce (Rockford, IL, USA). Lipid peroxidation assay kit was purchased from EMD Chemicals, Inc. (Gibbstown, NJ, USA). Protein carbonyl assay kit was purchased from Cayman Chemical Company (Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Silver nitrate and other reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA).

4.2. Implantation of brain infusion kit and osmotic pump

Adult ovariectomized SD rats were anesthetized via intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (60 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/ kg) and immobilized on a stereotaxic apparatus. A small incision was made through the scalp and a small hole drilled through the exposed skull. A stainless steel brain infusion cannula of 0.36 mm outer diameter was embedded into the right dorsal hippocampus by using stereotaxic surgery and fixed onto the skull. The cannula terminal coordinates, with the incisor bar set at −3.3 mm, were in millimeters from bregma and dura as follows: posterior 3.8, lateral 2.5, depth −3. For microinfusion of OA, a brain infusion kit and ALZET osmotic pump were used. A catheter tube was used to attach the cannula to the flow moderator of the ALZET pump, which is implanted subcutaneously. Before the placement of the cannula and osmotic pump, the brain infusion assembly and osmotic pump were prepared and filled with the appropriate OA solution (in artificial spinal–cerebral fluid containing 1% DMSO) for treatment groups: high dose (70 ng/day) and low dose (7 ng/ day). Control rats underwent the same procedure but received equal volume of vehicle. The osmotic pump has a 100-μl reservoir and 2 weeks in duration. The cannula position was verified by injecting a 10-μl solution of pontamine sky blue at the termination of the study. Ten minutes following the pontamine sky blue injection, the animals were decapitated, and the brains were harvested to verify that OA was infused into the dorsal hippocampus and for subsequent analysis.

4.3. Morris water maze

The Morris water maze (MWM) is a behavioral procedure designed to test spatial learning and memory. The test apparatus was a large circular pool (180 cm in diameter by 80 cm high) filled with water to a depth of 60 cm. The water was made opaque by the addition of approximately 0.5 L of nontoxic Crayola paint and thermostatically maintained at 24±1 °C. An 11×11-cm transparent platform 59-cm high was placed in a fixed location in the tank, 1 cm below the water surface. Many extramazecues surrounded themazeandwere availablefor the rats to use in locating the escape platform. A computerized tracking system (ANY-MAZE, Stoelting, IL, USA) was used to record the position of the rat. The testing was conducted in two phases: (1) a place discrimination acquisition phase in which the rat must learn and remember the location of the platform in space and (2) a retention phase in which the rat is tested for retention of the learned behavior after two days of no exposure to the apparatus. The acquisition phase consisted of 5 days, one session per day. Each session consisted of three trials, at 10-min intervals, during which the animal had to swim to the platform from one of four different starting points in the tank. Performance was measured as path length (distance traveled to reach the platform). The retention phase was performed 2 days following the acquisition period and consisted of one session per day for 2 days. In each trial, the rat was placed in the water, close to, and facing the wall of the pool in one of four equally spaced locations. The rat was allowed to swim freely around the pool until itfound the platform. Ifa rat fails to locate the platform within 90 seconds, it was then placed there by the experimenter.

4.4. Visible MWM test

Following the retention test, a visible platform test was conducted. The platform was identified by a visible flag that was elevated above the surface of the water. Three sessions were administered, each consisting of three trials at a 10-min intervals, 90 seconds per trial. In each trial, the rat had to swim to the platform from a different starting point in the tank, and the platform was also moved to a different location before each trial. The swimming distance to escape onto the platform was recorded.

4.5. Rotarod test

This task was used to assess motor coordination, balance, and motor learning. A motor-driven Accurotor Rotarod (Accuscan Instruments, Inc., Columbus, OH, USA) with a nylon cylinder (7 cm in diameter) was mounted horizontally at a fall height of 40 cm above a padded surface. The cylinder has four 11-cm-wide compartments separated by black acrylic dividers. The rotation of the cylinder was controlled by a microprocessor chip, which accelerates the rotation 0.5 rpm/s to the desired speed. Each rat was placed on the cylinder and the latency to fall was recorded. Rat were trained, three trials per day for 3 days with an intertrial interval of 10 min, to balance on the rotating rod at 10, 20, and 30 rpm for the first, second, and third days, respectively. The motor coordination and sustainability were assessed by the time to falling off the rod rotating at 30 rpm, averaged from three successive trials.

4.6. Bielschowsky’s silver staining

Following the termination of the behavioral testing, each rat brain was harvested for silver staining analysis. Each rat was perfused with 4% formaldehyde in PBS followed by immersion fixation of harvested brains for at least 24 hours before paraffin embedding. For neuropathological assessment, tissue blocks were embedded in paraffin and sectioned at a depth of 10 μm. Formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded sections were deparaffinized with xylene and rehydrated through a series decreasing concentrations of ethanol (100% to 0% ethanol). After three washings, the slides were placed in prewarmed (40 °C) 10% silver nitrate solution for 15 min until sections became a light brown color. The slides were washed an additional three times in distilled water. Concentrated ammonium hydroxide was added to the 10% silver nitrate solution drop by drop until solution became clear. The slides were placed back in the ammonium/silver solution and incubated for 30 min at 40 °C or until sections became dark brown. The slides were then placed directly into a freshly prepared developer working solution (1% concentrated ammonium hydroxide and 1% developer stock solution, which comprised of 20% formaldehyde, 0.5% citric acid, and 0.1% concentrated nitric acid) for a maximum of 1 min. After developing, the slides were dipped into 1% ammonium hydroxide solution for 1 min to terminate the reaction and washed three times with distilled water. After 5 min of incubation in 5% sodium thiosulfate solution followed by another set of three washes in distilled water, the slides were dehydrated and passed through 95% alcohol, 100% alcohol, and xylene, respectively. They were mounted with resinous medium.

4.7. Immunohistochemistry

Separate groups of rats were infused with OA for 14 days; then, rats were killed the following day without behavioral testing. The brain was removed and prepared for paraffin slices as described in section Bielschowsky’s silver staining. After deparaffinization and rehydration, the slides were placed boiling 10 mM sodium citrate buffer, pH 6.0, and maintained at a sub-boiling temperature for 10 min. Slides were cooled and then sections were incubated in 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 min. After washing three times, the slides were blocked with 5% normal goat serum in 1% BSA for 1 hour at room temperature. The blocking solution was removed, and we added appropriate primary antibody to each section and incubated overnight at 4 °C. The biotinylated secondary antibody was applied after removing of the primary antibody by three washings, and the slides were incubated for 30 min at room temperature, followed by removing of secondary antibody and washing. The ABC (avidin–biotin complex) reagent was applied to the tissue section with a 30-min incubation. The ABC reagent was washed off, and the Metal enhanced DAB substrate working solution was incubated until the desired staining was achieved. As soon as the sections developed, the slides were immersed in distilled water followed by dehydration through 95% alcohol, absolute alcohol, and xylene. Resinous medium was used to mount the coverslips.

4.8. Western blotting

For immunoblotting analysis, 14 days after OA dorsal hippocampal infusion, rats were sacrificed; the brain tissues were dissected into cortex and hippocampus, then homogenized in RIPA buffer (1× PBS, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 10 mg/ml aprotinin, 100 mg/ml phenylmethyl sulphonyl fluoride (PMSF)). Samples were centrifuged at 12,000×g for 30 min, and the supernatants were collected for Western blotting assay. Proteins from the brain tissues were separated by SDS–PAGE and transferred to Immunobilon-P polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) membranes. Membranes were blocked with 5% dry milk in PBS. Proteins were probed with specific antibodies at dilutions recommended by the manufacturer and incubated overnight at 4 °C. The blots were rinsed and applied with the appropriate secondary antibodies. After washing, the blots were developed with an enhanced chemiluminescent kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). ECL results were digitized and quantified by using UVP Bioimaging System (Upland, CA, USA). All the blots were normalized and semiqualified by beta-actin, which was probed and detected on the same blots after stripping and reblocking the membranes.

4.9. Lipid peroxidation assay

A colorimetric assay kit (cat. no. 437634) from Calbiochem was used to assay MDA content in the hippocampus and cortex. This assay takes advantage of a chromogenic reagent, N-methyl-2-phenylindole in acetonitrile, which reacts with MDA at 45 °C. Condensation of one molecule of MDA with two molecules of reagent N-methyl-2-phenylindole yields a stable chromophore with maximal absorbance at 586 nm. For tissue homogenates preparation, the cortex and hippocampi were separated from the rat brain and put into ice-cold Tris buffer (20 mM, pH 7.4) at 1:10 (wt./vol.). Prior to homogenization, butylated hydroxyl toluene (BHT) was added to a final concentration of 5 mM to the buffer in order to prevent sample oxidation during the homogenization. Homogenates were centrifuged (3000×g at 4 °C for 10 min). The clear supernatant was collected for the lipid peroxidation assay and protein assay. For MDA measurement, 200 μl of sample was added into a clean test tube followed by adding 650 μl of solution containing one volume of ferric ion in methanol and three volumes of N-methyl-2-phenylindole in acetonitrile, and then 150 μl of 12 N HCl was added. After mixing, the testing tubes were incubated at 45 °C for 60 min. Samples were cooled on ice, and absorbance was measured at 586 nm. For each sample, there was a sample blank where the 650 μl of solution (25% ferric ion in methanol/75% N-methyl-2-phenylindole in acetonitrile) was replaced by 650 μl of 25% methanol/75% acetonitrile, and a reagent blank where the sample was replaced by water. A standard curve was created by measuring the absorbance of a series of concentration of MDA at 586 nm. The color yielded was a linear function of the MDA concentration over the range from 0 to 20 μM.

4.10. Protein carbonyl assay

A protein carbonyl assay kit (cat. no.10005020) from Cayman Chemical was used to assay brain protein carbonyl content. For tissue homogenate preparation, cortex and hippocampus were separated from the rat brain and put into ice-cold buffer (50 mM phosphate, pH 6.7 containing 1 mM EDTA) at 1:10 (wt./ vol.). After homogenization and centrifugation at 10,000×g for 15 min at 4 °C, the supernatant was collected for the assay. Supernatant absorbance was determined at 280 nm and 260 nm to assess contamination by nucleic acids. The homogenization buffer was used as a blank. If the ratio 280/260 nm was less than 1, a further step to remove nucleic acids with 1% streptomycin sulfate was used. Two hundred microliters of sample was transferred to two 2.0-ml plastic tubes. One tube was the sample tube, and the other was the control tube. Eight hundred microliters of DNPH was added to the sample tube while adding 800 μl of 2.5 N HCl to the control tube. Both tubes were incubated in the dark at room temperature for one hour with vortexing briefly every 15 min. After incubation, 1 ml of 20% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) was added to each tube on ice. Five minutes later, tubes were centrifuged at 10,000×g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was resuspended in 1 ml of 10% TCA on ice for 5 min. Tubes were centrifuged again at 10,000×g for 15 min at 4 °C, and the pellet was resuspended in 1 ml of (1:1) ethanol/ethyl acetate mixture. This step was repeated two more times. After the final wash, the protein pellets was resuspended in 500 μl of guanidine hydrochloride by vortexing. Tubes were centrifuged at 10,000×g for 15 min at 4 °C to remove any leftover debris. Two hundred twenty microliters of supernatant was transferred to a 96-well plate, and absorbance was measured at 360 nm. The carbonyl content was calculated using a molar extinction coefficient of 22 per millimolar per centimeter for DNPH and was expressed as nanomolar of DNPH per milligram of protein.

4.11. Statistics

Statistical significance was determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison tests. p<0.05 was considered significant for all experiments. The values are expressed as mean±SEM.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH grants P01 AG10485, P01 AG22550, and P01 AG27956.

Abbreviations

- OA

okadaic acid

- cdk5

cyclin-dependent kinase 5

- GSK-3

glycogen synthase kinase-3

- NFTs

neurofibrillary tangle

References

- Abrahams S, Pickering A, Polkey CE, Morris RG. Spatial memory deficits in patients with unilateral damage to the right hippocampal formation. Neuropsychologia. 1997;35:11–24. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(96)00051-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahlijanian MK, Barrezueta NX, Williams RD, Jakowski A, Kowsz KP, McCarthy S, Coskran T, Carlo A, Seymour PA, Burkhardt JE, Nelson RB, McNeish JD. Hyperphosphorylated tau and neurofilament and cytoskeletal disruptions in mice overexpressing human p25, an activator of cdk5. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:2910–2915. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040577797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-de-la-Rosa M, Silva I, Nilsen J, Perez MM, Garcia-Segura LM, Avila J, Naftolin F. Estradiol prevents neural tau hyperphosphorylation characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1052:210–224. doi: 10.1196/annals.1347.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arendt T, Holzer M, Bruckner MK, Janke C, Gartner U. The use of okadaic acid in vivo and the induction of molecular changes typical for Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience. 1998a;85:1337–1340. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00697-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arendt T, Holzer M, Fruth R, Bruckner MK, Gartner U. Phosphorylation of tau, abeta-formation, and apoptosis after in vivo inhibition of PP-1 and PP-2A. Neurobiol Aging. 1998b;19:3–13. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(98)00003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arriagada PV, Growdon JH, Hedley-Whyte ET, Hyman BT. Neurofibrillary tangles but not senile plaques parallel duration and severity of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1992;42:631–639. doi: 10.1212/wnl.42.3.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avila J, Lucas JJ, Perez M, Hernandez F. Role of tau protein in both physiological and pathological conditions. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:361–384. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00024.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudier J, Cole RD. Phosphorylation of tau proteins to a state like that in Alzheimer’s brain is catalyzed by a calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase and modulated by phospholipids. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:17577–17583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billingsley ML, Kincaid RL. Regulated phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of tau protein: effects on microtubule interaction, intracellular trafficking and neurodegeneration. Biochem J. 1997;323(Pt 3):577–591. doi: 10.1042/bj3230577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohbot VD, Kalina M, Stepankova K, Spackova N, Petrides M, Nadel L. Spatial memory deficits in patients with lesions to the right hippocampus and to the right parahippocampal cortex. Neuropsychologia. 1998;36:1217–1238. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(97)00161-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt R, Hundelt M, Shahani N. Tau alteration and neuronal degeneration in tauopathies: mechanisms and models. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1739:331–354. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2004.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellani RJ, Lee HG, Zhu X, Perry G, Smith MA. Alzheimer disease pathology as a host response. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2008;67:523–531. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e318177eaf4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correas I, Diaz-Nido J, Avila J. Microtubule-associated protein tau is phosphorylated by protein kinase C on its tubulin binding domain. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:15721–15728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devred F, Barbier P, Douillard S, Monasterio O, Andreu JM, Peyrot V. Tau induces ring and microtubule formation from alphabeta-tubulin dimers under nonassembly conditions. Biochemistry. 2004;43:10520–10531. doi: 10.1021/bi0493160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drewes G, Lichtenberg-Kraag B, Doring F, Mandelkow EM, Biernat J, Goris J, Doree M, Mandelkow E. Mitogen activated protein (MAP) kinase transforms tau protein into an Alzheimer-like state. EMBO J. 1992;11:2131–2138. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05272.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duff K, Planel E. Untangling memory deficits. Nat Med. 2005;11:826–827. doi: 10.1038/nm0805-826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filley CM. Alzheimer’s disease in women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(97)80003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goedert M, Spillantini MG, Jakes R, Rutherford D, Crowther RA. Multiple isoforms of human microtubule-associated protein tau: sequences and localization in neurofibrillary tangles of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron. 1989;3:519–526. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90210-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goedert M, Jakes R, Vanmechelen E. Monoclonal antibody AT8 recognises tau protein phosphorylated at both serine 202 and threonine 205. Neurosci Lett. 1995;189:167–169. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11484-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong CX, Grundke-Iqbal I, Damuni Z, Iqbal K. Dephosphorylation of microtubule-associated protein tau by protein phosphatase-1 and -2C and its implication in Alzheimer disease. FEBS Lett. 1994a;341:94–98. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)80247-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong CX, Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K. Dephosphorylation of Alzheimer’s disease abnormally phosphorylated tau by protein phosphatase-2A. Neuroscience. 1994b;61:765–772. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90400-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong CX, Singh TJ, Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K. Alzheimer’s disease abnormally phosphorylated tau is dephosphorylated by protein phosphatase-2B (calcineurin) J Neurochem. 1994c;62:803–806. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.62020803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong CX, Liu F, Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K. Dysregulation of protein phosphorylation/dephosphorylation in Alzheimer’s disease: a therapeutic target. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2006;2006:31825. doi: 10.1155/JBB/2006/31825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimes CA, Jope RS. The multifaceted roles of glycogen synthase kinase 3beta in cellular signaling. Prog Neurobiol. 2001;65:391–426. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(01)00011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K, Quinlan M, Tung YC, Zaidi MS, Wisniewski HM. Microtubule-associated protein tau. A component of Alzheimer paired helical filaments. J Biol Chem. 1986a;261:6084–6089. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K, Tung YC, Quinlan M, Wisniewski HM, Binder LI. Abnormal phosphorylation of the microtubule-associated protein tau (tau) in Alzheimer cytoskeletal pathology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986b;83:4913–4917. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.13.4913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanger DP, Hughes K, Woodgett JR, Brion JP, Anderton BH. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 induces Alzheimer’s disease-like phosphorylation of tau: generation of paired helical filament epitopes and neuronal localisation of the kinase. Neurosci Lett. 1992;147:58–62. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90774-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J, Yang Y, Xu H, Zhang X, Li XM. Olanzapine attenuates the okadaic acid-induced spatial memory impairment and hippocampal cell death in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:1511–1520. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez F, Avila J. Tauopathies. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:2219–2233. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7220-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiguro K, Shiratsuchi A, Sato S, Omori A, Arioka M, Kobayashi S, Uchida T, Imahori K. Glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta is identical to tau protein kinase I generating several epitopes of paired helical filaments. FEBS Lett. 1993;325:167–172. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81066-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson GV, Stoothoff WH. Tau phosphorylation in neuronal cell function and dysfunction. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:5721–5729. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lace G, Savva GM, Forster G, de Silva R, Brayne C, Matthews FE, Barclay JJ, Dakin L, Ince PG, Wharton SB on behalf of MRC-CFAS. Hippocampal tau pathology is related to neuroanatomical connections: an ageing population-based study. Brain. 2009;132:1324–1334. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Matsumoto K, Watanabe H. Different effects of unilateral and bilateral hippocampal lesions in rats on the performance of radial maze and odor-paired associate tasks. Brain Res Bull. 1999;48:113–119. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(98)00157-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CF, Chen CL, Chiang CW, Jan MS, Huang WC, Lin YS. GSK-3beta acts downstream of PP2A and the PI 3-kinase–akt pathway, and upstream of caspase-2 in ceramide-induced mitochondrial apoptosis. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:2935–2943. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K, Gong CX. Contributions of protein phosphatases PP1, PP2A, PP2B and PP5 to the regulation of tau phosphorylation. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22:1942–1950. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M, Choi S, Cuny GD, Ding K, Dobson BC, Glicksman MA, Auerbach K, Stein RL. Kinetic studies of Cdk5/p25 kinase: phosphorylation of tau and complex inhibition by two prototype inhibitors. Biochemistry. 2008;47:8367–8377. doi: 10.1021/bi800732v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovestone S, Reynolds CH. The phosphorylation of tau: a critical stage in neurodevelopment and neurodegenerative processes. Neuroscience. 1997;78:309–324. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00577-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas JJ, Hernandez F, Gomez-Ramos P, Moran MA, Hen R, Avila J. Decreased nuclear beta-catenin, tau hyperphosphorylation and neurodegeneration in GSK-3beta conditional transgenic mice. EMBO J. 2001;20:27–39. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manns JR, Hopkins RO, Reed JM, Kitchener EG, Squire LR. Recognition memory and the human hippocampus. Neuron. 2003a;37:171–180. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01147-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manns JR, Hopkins RO, Squire LR. Semantic memory and the human hippocampus. Neuron. 2003b;38:127–133. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00146-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markesbery WR, Carney JM. Oxidative alterations in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Pathol. 1999;9:133–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1999.tb00215.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques CM, Caboclo LO, da Silva TI, Noffs MH, Carrete H, Jr, Lin K, Lin J, Sakamoto AC, Yacubian EM. Cognitive decline in temporal lobe epilepsy due to unilateral hippocampal sclerosis. Epilepsy Behav. 2007;10:477–485. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morishima-Kawashima M, Hasegawa M, Takio K, Suzuki M, Yoshida H, Titani K, Ihara Y. Proline-directed and non-proline-directed phosphorylation of PHF-tau. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:823–829. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.2.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser E, Moser MB, Andersen P. Spatial learning impairment parallels the magnitude of dorsal hippocampal lesions, but is hardly present following ventral lesions. J Neurosci. 1993;13:3916–3925. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-09-03916.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser MB, Moser EI, Forrest E, Andersen P, Morris RG. Spatial learning with a minislab in the dorsal hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:9697–9701. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.21.9697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mudher A, Lovestone S. Alzheimer’s disease—do Tauists and Baptists finally shake hands? Trends Neurosci. 2002;25:22–26. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)02031-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadel L. The hippocampus and space revisited. Hippocampus. 1991;1:221–229. doi: 10.1002/hipo.450010302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy Z, Esiri MM, Jobst KA, Morris JH, King EM, McDonald B, Litchfield S, Smith A, Barnetson L, Smith AD. Relative roles of plaques and tangles in the dementia of Alzheimer’s disease: correlations using three sets of neuropathological criteria. Dementia. 1995;6:21–31. doi: 10.1159/000106918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunomura A, Castellani RJ, Zhu X, Moreira PI, Perry G, Smith MA. Involvement of oxidative stress in Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2006;65:631–641. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000228136.58062.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick GN, Zukerberg L, Nikolic M, de la Monte S, Dikkes P, Tsai LH. Conversion of p35 to p25 deregulates Cdk5 activity and promotes neurodegeneration. Nature. 1999;402:615–622. doi: 10.1038/45159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paudel HK, Lew J, Ali Z, Wang JH. Brain proline-directed protein kinase phosphorylates tau on sites that are abnormally phosphorylated in tau associated with Alzheimer’s paired helical filaments. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:23512–23518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Planel E, Yasutake K, Fujita SC, Ishiguro K. Inhibition of protein phosphatase 2A overrides tau protein kinase I/glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta and cyclin-dependent kinase 5 inhibition and results in tau hyperphosphorylation in the hippocampus of starved mouse. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:34298–34306. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102780200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratico D. Evidence of oxidative stress in Alzheimer’s disease brain and antioxidant therapy: lights and shadows. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1147:70–78. doi: 10.1196/annals.1427.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rissman EF, Heck AL, Leonard JE, Shupnik MA, Gustafsson JA. Disruption of estrogen receptor beta gene impairs spatial learning in female mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:3996–4001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012032699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santacruz K, Lewis J, Spires T, Paulson J, Kotilinek L, Ingelsson M, Guimaraes A, DeTure M, Ramsden M, McGowan E, Forster C, Yue M, Orne J, Janus C, Mariash A, Kuskowski M, Hyman B, Hutton M, Ashe KH. Tau suppression in a neurodegenerative mouse model improves memory function. Science. 2005;309:476–481. doi: 10.1126/science.1113694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayre LM, Zelasko DA, Harris PL, Perry G, Salomon RG, Smith MA. 4-hydroxynonenal-derived advanced lipid peroxidation end products are increased in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem. 1997;68:2092–2097. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68052092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton SB, Johnson GV. Cyclin-dependent kinase-5 in neurodegeneration. J Neurochem. 2004;88:1313–1326. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2003.02328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh M, Dykens JA, Simpkins JW. Novel mechanisms for estrogen-induced neuroprotection. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2006;231:514–521. doi: 10.1177/153537020623100505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MA, Rottkamp CA, Nunomura A, Raina AK, Perry G. Oxidative stress in Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1502:139–144. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(00)00040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhilb ML, Dias-Santagata D, Fulga TA, Felch DL, Feany MB. Tau phosphorylation sites work in concert to promote neurotoxicity in vivo. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:5060–5068. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-04-0327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, Liu SY, Zhou XW, Wang XC, Liu R, Wang Q, Wang JZ. Inhibition of protein phosphatase 2A- and protein phosphatase 1-induced tau hyperphosphorylation and impairment of spatial memory retention in rats. Neuroscience. 2003;118:1175–1182. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00697-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai LH, Delalle I, Caviness VS, Jr, Chae T, Harlow E. P35 is a neural-specific regulatory subunit of cyclin-dependent kinase 5. Nature. 1994;371:419–423. doi: 10.1038/371419a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida T, Ishiguro K, Ohnuma J, Takamatsu M, Yonekura S, Imahori K. Precursor of cdk5 activator, the 23 kDa subunit of tau protein kinase II: its sequence and developmental change in brain. FEBS Lett. 1994;355:35–40. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)01163-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weingarten MD, Lockwood AH, Hwo SY, Kirschner MW. A protein factor essential for microtubule assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1975;72:1858–1862. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.5.1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen Y, Yang S, Liu R, Brun-Zinkernagel AM, Koulen P, Simpkins JW. Transient cerebral ischemia induces aberrant neuronal cell cycle re-entry and Alzheimer’s disease-like tauopathy in female rats. J Biol Chem. 2004a;279:22684–22692. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311768200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen Y, Yang S, Liu R, Simpkins JW. Transient cerebral ischemia induces site-specific hyperphosphorylation of tau protein. Brain Res. 2004b;1022:30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.05.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodgett JR. Molecular cloning and expression of glycogen synthase kinase-3/factor A. EMBO J. 1990;9:2431–2438. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07419.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S, Sasaki A, Yoshimoto R, Kawahara Y, Manabe T, Kataoka K, Asashima M, Yuge L. Neural stem cells improve learning and memory in rats with Alzheimer’s disease. Pathobiology. 2008;75:186–194. doi: 10.1159/000124979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Simpkins JW. Okadaic acid induces tau phosphorylation in SH-SY5Y cells in an estrogen-preventable manner. Brain Res. 2010;1345:176–181. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.04.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Raina AK, Perry G, Smith MA. Alzheimer’s disease: the two-hit hypothesis. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3:219–226. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00707-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Lee HG, Perry G, Smith MA. Alzheimer disease, the two-hit hypothesis: an update. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1772:494–502. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2006.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]