Abstract

The ‘one neuron, one neurotransmitter’ doctrine states that synaptic communication between two neurons occurs via the release of a single chemical transmitter. However, recent findings suggest that neurons that communicate using more than one classical neurotransmitter are prevalent throughout the adult mammalian CNS. In particular, several populations of neurons previously thought to release only glutamate, acetylcholine, dopamine or histamine also release the major inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA. Here, we review these findings and discuss the implications of GABA co-release for synaptic transmission and plasticity.

Neurons in the vertebrate and invertebrate nervous systems contain and release several small molecule and peptide transmitters, each capable of signaling through a variety of receptors. A distinction is often made between classical small-molecule neurotransmitters, including glutamate, GABA, glycine, acetylcholine (Ach), purines and monoamines, which serve as the primary means of transferring electrical signals between synaptic partners, and neuropeptides such as somatostatin, neuropeptide Y, substance P and enkaphalin (amongst many others), which slowly alter the properties of target neurons by activating G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). It has been established for several decades that exocytosis of one or more neuropeptide accompanies the release of classical small-molecule neurotransmitters in most neurons1.

Nevertheless, our understanding of neural function and rapid synaptic communication has been dominated by the idea that a neuron releases a single classical neurotransmitter at all of its synapses – a notion commonly known as Dale’s principle (BOX 1). This principle has helped reduce the complexity of the nervous system by assigning each neuron to one of three functional categories: excitatory, inhibitory, or modulatory. However, several important facts complicate the simple characterization of neurons in this way. First, excitatory and inhibitory neurons are also capable of modulatory functions, because glutamate, GABA, ACh and purines can activate GPCRs in addition to ligand-gated ion channels. Second, the synaptic actions of individual neurons vary with developmental age, membrane potential, cellular identity, and the biochemical state of the postsynaptic cell. Third, in nervous system of invertebrates and in the peripheral nervous system and developing CNS of vertebrates, many neuronal populations have been shown to release more than one classical neurotransmitter1–4. However, the prevalence and physiological role of such co-release in the adult mammalian CNS are less well established. In this Progress article, we discuss recent reports of neuronal populations in the rodent adult CNS that co-release GABA, examine the molecular mechanisms involved, and consider the functional significance of GABAergic co-transmission for neuronal communication and circuit computations.

Box 1. In defense of Sir Henry Dale.

In the early 1900s, Otto Loewi (1873–1961) observed that stimulation of frog parasympathetic and sympathetic nerves evoked the release of substances that inhibited or accelerated heart rate, respectively. Henry Dale (1875–1968) subsequently helped identify the released transmitters —acetylcholine and noradrenaline —and coined the terms ‘cholinergic’ and ‘adrenergic’ to describe nervous systems that liberated these molecules. These findings, which earned Loewi and Dale the 1936 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, established the chemical basis of neurotransmission and fostered the concept that neurons have distinct chemical identities that specify their function. Dale is often cited for proposing that each neuron releases a single classical transmitter—a rule that is increasingly proving not to hold. However, in his defense, Dale recognized the possibility that nerves liberate more than one molecule, and never explicitly formulated or embraced the principle that has become synonymous with his name70. In fact, the phrase ‘Dale’s principle’ was introduced by John Eccles (1903–1997) in 1954 in reference to Dale’s hypothesis that neurons release the same transmitter (or set of transmitters) across all of their synapses. Interestingly, recent work10, 38, 71 suggests that this may not be universally true.

Defining co-release

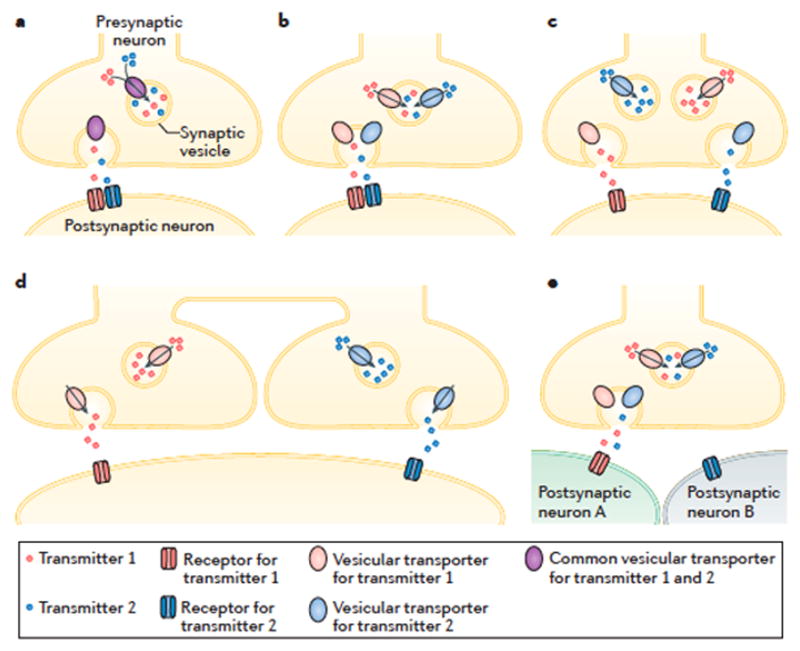

The term neurotransmitter co-release describes the process by which two (or more) neurotransmitters are released by a single neuron in response to an action potential. This description emphasizes the mechanism involved, and is restricted to the release of neurotransmitters by vesicular exocytosis4. Co-release results from packaging multiple transmitters into individual synaptic vesicles or from the coincident membrane fusion of different vesicles filled with distinct neurotransmitters (FIG. 1a–d). Because small molecule transmitters and neuropeptides are often distributed to separate vesicular compartments (clear synaptic vesicles and large dense core vesicles) and differentially mobilized by intracellular Ca2+ (see REF. 2), the term co-release typically applies to exocytosis of two classical neurotransmitters.

Figure 1. Distinct cellular and molecular mechanisms of co-transmission.

Although it is often difficult to identify co-transmission experimentally using electrophysiological and anatomical approaches, there are several possible mechanisms by which co-transmission of two neurotransmitters might occur, each offering distinct functionality and plasticity. a|The transmitters may be loaded into individual synaptic vesicles using a common vesicular transporter. The abundance of the transmitters in the cytosol and transporter affinity for those transmitters will determine the relative content of synaptic vesicles. Such co-packaging ensures that both transmitters are released at the same time and location, and are subject to similar presynaptic short-term plasticity. b|The transmitters may be packaged into individual vesicles using distinct vesicular transporters. The relative abundance of each co-transmitter in vesicles varies with cytosolic transmitter availability and with the expression levels of the vesicular transporters. Unless all vesicles express both transporters, this type of co-packaging likely occurs together with the co-packaging described in part c. c| The transmitters may be packaged into separate vesicles that are found within individual presynaptic boutons. Although both transmitters would be exocytosed from the same presynaptic bouton, their release could be modulated independently over short and long time scales, depending on transmitter abundances, synaptic vesicle release probability and the rate of synaptic vesicle recycling and loading for each transmitter. d|The transmitters may be packaged into separate vesicles that distribute to distinct presynaptic release sites. Physical separation would allow the presynaptic release of both transmitters to be modulated separately, and the targeting of each transmitter to different postsynaptic compartments. For example, glutamate release may target dendritic spines while GABA is exocytosed onto dendritic shafts. e|An example of transmitter co-release that does not result in synaptic co-transmission is depicted, in which postsynaptic membranes (cell A and cell B) express receptors for only one of the two transmitters. This mechanism enables presynaptic neurons to broadcast a signal that is differentially interpreted by distinct neuronal elements.

The term co-transmission also refers to synaptic release of multiple substances from a single cell, but it does not specify mechanism and therefore also extends to gaseous transmitters. It does, however, emphasize function, as it implies that both transmitters contribute to synaptic transmission, either by evoking postsynaptic electrical responses, or by modulating the excitability of pre- and postsynaptic membranes1. Hence, co-release might not result in co-transmission if the target cell does not express receptors for both transmitters (FIG. 1e). We note that the relative ease with which fast synaptic currents can be detected experimentally, compared with the detection of slow modulatory influences, has biased the study of co-transmission to classical neurotransmitters acting on ionotropic receptors.

Examples of GABA co-release

At a minimum, the co-release of two neurotransmitters requires that presynaptic terminals express the molecular machinery necessary to acquire both transmitters and to package them into synaptic vesicles. GABA is typically synthesized from glutamate by glutamate decarboxylase 65 kDa isoform (GAD65, encoded by Gad2) and/or glutamate decarboxylase 67 kDa isoform (GAD67, encoded by Gad1) and transported into synaptic vesicles using the vesicular GABA transporter (VGAT, encoded by Slc32a1)5. The degree of plasma membrane uptake of GABA and glutamate has also been shown to influence the amount of GABA that is exocytosed, particularly during sustained synaptic stimulation6–8. GABA signals through Cl− permeable GABAA and GABAC receptors, as well as Gαi/o-coupled GABAB receptors. In this section, we summarize the classical neurotransmitter systems in which the co-release of GABA has been observed in the adult mammalian CNS and discuss the molecular and cellular mechanisms involved in each example.

Glycine–GABA

Functional co-release of GABA and glycine in the adult CNS was first reported in the late 1990s and has since been extensively documented in several neuronal populations in the spinal cord, brainstem and cerebellum (reviewed in REF 4). Glycine and GABA are released from the same synaptic vesicles, as both neurotransmitters utilize VGAT for packaging into synaptic vessicles5 (FIG. 1a). The relative contribution of each of these transmitters to neurotransmission at individual synapses varies with the local presynaptic concentration of GABA and glycine, and with the density and composition of postsynaptic receptors8–10.

Glutamate–GABA

Classically, it is thought that glutamate and GABA are released from distinct sets of excitatory and inhibitory neurons in the adult CNS. However, despite the opposing functions of these neurotransmitters, two recent reports describe the co-release of glutamate and GABA from individual CNS axons. Neurons in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and entopeduncular nucleus (EP) were recently shown to release both glutamate and GABA onto neurons in the lateral habenula (LHb)11, 12. Activation of fibers from VTA most frequently resulted in short latency suppression of firing in LHb neurons. By contrast, stimulation of EP inputs reliably evoked spiking in LHb neurons, reflecting a predominantly excitatory mode of action. Interestingly, the ratio of GABAergic to glutamatergic signaling from EP decreased in animal models of depression and increased in response to treatment with the antidepressant citalopram11. These findings add to a growing literature implicating LHb dysfunction in major depressive disorders13, and suggest that changes in glutamate-GABA co-release within LHb might serve as a therapeutic target for these illnesses.

Most axons from EP and VTA that terminate in LHb co-express vesicular transporters for GABA and glutamate11, 12, indicating that individual synapses are capable of packaging and releasing both transmitters. Shabel and colleagues occasionally observed quantal synaptic events with biphasic waveforms11, providing compelling functional evidence that GABA and glutamate are co-packaged at some release sites in LHb (FIG. 1b). It is, however, difficult to experimentally exclude the possibility that there are also intermingled synaptic vesicles preferentially enriched with one or the other transmitter (FIG. 1c). Interestingly, individual mesohabenular boutons establish symmetric and asymmetric postsynaptic contacts enriched in GABAA and glutamate receptors, respectively, which is suggestive of a postsynaptic division of labor12. The finding that multiple synaptic inputs into this small brain area share the peculiar property of releasing both GABA and glutamate suggests that co-release may confer a specific function on this region.

Acetylcholine–GABA

Cholinergic neurons in the CNS have long been suspected of co-releasing GABA, based on extensive co-expression of GABAergic and cholinergic markers in many vertebrate species14. Unambiguous functional evidence of co-release was found in an elegant study of the mouse retina that demonstrated, using paired whole-cell recordings, that monosynaptic GABAergic and cholinergic transmission occurs from starburst amacrine cells (SACs) onto direction-sensitive retinal ganglion cells (DSGCs)15. Interestingly, this study revealed that vesicular release of GABA and ACh is differentially regulated by intracellular Ca2+, and is spatially uncoupled: whereas ACh transmission is reliably evoked in [AU: OK?] all SAC-DSGC pairs, GABA release occurs preferentially in response to visual stimuli moving in one particular direction, and is significantly biased to one half of the radial dendritic tree of a DSGC15. The spatial bias emerges from asymmetric development of SAC GABAergic synapses onto DSGCs16, 17. These data strongly suggest that SACs package GABA and ACh into distinct populations of synaptic vesicles that distribute to non-overlapping, or partially-overlapping presynaptic terminals (FIG. 1d).

More recently, functional evidence of co-release of GABA and ACh has been found in the cortex of mice, which receives most of its cholinergic input from basal forebrain projection neurons. Optogenetic activation of cholinergic fibers in general18, or of cholinergic fibers originating in globus pallidus specifically19, evoked postsynaptic responses in inhibitory cortical interneurons mediated by both GABAA and nicotinic ACh receptors. The short onset latency and pharmacological properties of GABAergic currents suggest that cholinergic fibers directly release GABA. As in the retina, cortical ACh–GABA co-release appears to occur through separate populations of synaptic vesicles, because individual cortical interneurons often exhibited responses to only one transmitter, and labeling of cholinergic presynaptic terminals from the globus pallidus showed spatial segregation of vesicular transporters for GABA and ACh18, 19. However, further research is required to determine the precise presynaptic mechanism and postsynaptic targets of ACh– GABA co-release in cortex.

Dopamine–GABA

Dopamine is synthesized from tyrosine by the enzymes tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) and aromatic-L-amino-acid decarboxylase (AADC) and is loaded into synaptic vesicles via the vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2, encoded by Slc18a2). The identification of neurons capable of releasing dopamine has historically centered on labeling TH in neurons and, more recently, on the use of mice expressing transgenes under the control of the TH promoter. These approaches revealed that a surprisingly high number of TH-expressing cells also express GADs, and might therefore co-release GABA20. However, careful analyses revealed that low levels of TH mRNA are transcribed in many neurons during development and in adulthood without generating detectable amounts of TH protein or dopamine, and that several populations of TH-expressing neurons in cortex, striatum, hypothalamus, and midbrain lack expression of AADC and VMAT2, and the ability to release dopamine20–23. Therefore care should therefore be taken when determining the neurochemical identity of a cell and identifying neuronal candidates for co-release in the adult brain. This is generally true for all optogenetic studies, as non-specific opsin expression in even a small number of off-target cells could easily be misinterpreted as co-release from one population of neurons24.

Nevertheless, functional evidence of co-release of dopamine and GABA has been found in several brain areas. The olfactory bulb and retina contain populations of cells that express GADs, TH, VGAT and VMAT2. Depolarization of these neurons results in the release of both transmitters from small clear vesicles in a Ca2+-dependent fashion25–28. Interestingly, quantal release of dopamine and GABA is mostly asynchronous — the release of dopamine outlasts GABA exocytosis by several seconds26, 27 — suggesting that packaging into largely non-overlapping synaptic vesicles occurs (FIG. 1c).

We recently reported that dopamine-containing neurons in the VTA and substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) monosynaptically inhibit spiny projection neurons (SPNs) in the striatum through Ca2+-dependent release of a GABAA receptor agonist29, 30. Dopamine does not gate Cl− conductances in striatal neurons29, 31 and several lines of evidence instead suggest that GABA is the released transmitter30. However, whereas GABA synthetic enzymes have been observed in a small fraction of SNc and VTA neurons in rat32, striatum-projecting dopaminergic neurons in mice do not contain detectable levels of GAD65, GAD67 or VGAT mRNA or protein23, 29, 30, 33, which raises the question of how SNc and VTA neurons acquire and package GABA for exocytosis. Our studies revealed that VMAT2 is necessary for GABAergic transmission from nigrostriatal afferents and restores vesicular release of GABA when re-expressed in GABAergic neurons from which VGAT had been knocked out [AU: OK?]29. VMAT2 shows homology to a large family of transporters that expel chemicals from cells, and it is the most promiscuous of the vesicular neurotransmitter transporters, with over a dozen reported substrates, including ecstasy, ethidium and rhodamine34. VMAT2 – or a molecular complex incorporating VMAT2 – may therefore transport GABA into synaptic vesicles, raising the possibility that GABA and dopamine are co-packaged in SNc and VTA axons (FIG. 1a). In agreement with this possibility, ultrastructural studies detected GABA associated with VMAT2-containing synaptic vesicles within dopaminergic terminals35. Additional biochemical studies are needed to determine the relative affinity of GABA for VMAT2, and whether other proteins also enable VMAT2-dependent transport of GABA. The absence of such a co-factor in neurons containing dopamine and GABA in the retina and olfactory bulb could explain why co-packaging is not observed more frequently in these cells26, 27.

Midbrain dopaminergic neurons express several genes typically found in neurons that release GABA36, including plasma membrane GABA transporters, which are involved in terminating the synaptic actions of GABA30. In mice, these transporters are also required to sustain GABAergic transmission from SNc neurons30, suggesting that reuptake is an important means of supplying GABA for exocytosis. This mechanism may allow the degree of GABAergic transmission to vary along dopaminergic axons, depending on extracellular GABA levels or the membrane distribution of the GABA transporter37. The latter may explain why striatal cholinergic neurons do not receive GABAergic co-transmission from SNc axons38, despite expressing GABAA receptors and receiving dopaminergic innervation39.

A recent study by Kim and colleagues40 supports the finding that mouse midbrain dopaminergic neurons do not express GADs23, 29, 30, 33, and reveals a non-canonical pathway for the synthesis of GABA via aldehyde dehydrogenase 1a1 (ALDH1a1). Pharmacological inhibition, global genetic deletion, and midbrain knockdown of ALDH1a1 in mice all reduced GABA release from SNc axons by half, and the administration of GABA reuptake blockers abolished the remaining GABA release, indicating that ALDH1a1 and membrane GABA transporters both contribute to the cytosolic accumulation of GABA for exocytosis40. Interestingly, dopamine release is also dependent on both de novo synthesis and membrane reuptake41. In addition, the study by Kim et al. 40 reported that prolonged incubation of acute brain slices in ethanol depresses GABA co-release from SNc axons, and that this effect requires ALDH1a1. Furthermore, in a continuous two-bottle-choice test in their home cage, mice lacking ALDH1a1 consumed more alcohol than wild-type controls, suggesting a functional role for GABA co-release in regulating behavioral responses to alcohol.

Co-release of GABA may also occur in other populations of dopaminergic neurons in the mammalian CNS, as dopaminergic nuclei A11–A14 all express GADs20. Although the presence of VMAT2 alone should render these cells capable of releasing both transmitters, they may also express VGAT. Co-expression of both vesicular transporters might allow for the presence of separate pools of vesicles enriched with each neurotransmitter. These observations support a large body of work in several species indicating that there is significant overlap in the expression of dopaminergic and GABAergic markers in the developing and mature nervous systems, under both physiological and pathological conditions42–45, which collectively suggest that GABA is a ubiquitous co-transmitter in dopaminergic neurons[AU: OK?].

Histamine–GABA

Neurons of the tuberomammilary nucleus (TMN), which are the only source of histamine in the vertebrate CNS, exhibit a GABAergic phenotype based on the expression of GABA, GAD67 and VGAT46, 47. However, functional evidence of GABA release from these cells has remained elusive. Electrical stimulation of TMN neurons elicits inhibitory postsynaptic potentials in supraoptic nucleus neurons that are insensitive to the GABAA receptor antagonist bicuculine48, and optogenetic activation of TMN neurons fails to evoke phasic GABAergic responses locally within TMN, in preoptic nucleus target neurons or in cortical pyramidal neurons, despite evidence of histamine release in those areas47, 49. This may reflect the fact that TMN axonal varicosities are not typically found closely apposed to postsynaptic structures46, preventing the efficient detection of co-released GABA. Alternatively, GABA and histamine may be packaged into distinct organelles in TMN neurons50 and released onto different targets that remain to be identified.

A recent study by Yu and colleagues, however, indicated that GABA co-release might participate in the control of arousal and wakefulness by neurons of the TMN by ablating VGAT from these cells in mice47. Recordings from cortical and striatal neurons in slices from wild-type mice revealed a slow and sustained increase in holding current upon prolonged optical stimulation of TMN axons (900 light pulses over 3 min) that was mediated by GABAA receptors. This current was dependent on transmitter release from TMN axons, was partially blocked by the inclusion of H1 and H2 histamine receptor antagonists, and was not observed in slices from mice with genetic deletion of VGAT in the TMN, providing the first functional evidence that GABA may be co-released by TMN neurons. However, two caveats should be noted that prevent more definitive conclusions being drawn from this study. First, the authors did not exclude a contribution of H3 receptors to the postsynaptic response to TMN stimulation; H3 receptors are widely expressed, and might contribute to the accumulation of extracellular GABA by stimulating the release of GABA from cortical interneurons or by preventing its reuptake. Second, the experiments that established the dependence of TMN stimulation-induced cortical and striatal responses on the expression of VGAT involved comparisons between two separate strains of mice, viral vectors and specificity of opsin expression. It is therefore difficult to assess whether TMN neurons were recruited to a similar extent under both conditions. In addition, the small magnitude of the induced GABAergic currents complicates the assessment of the contribution by VMAT2 to these currents, as VMAT2 presumably does not transport GABA as efficiently as VGAT[AU: OK?].

Functions of GABA co-release

GABA is a remarkably versatile neurotransmitter; it can exert excitatory, inhibitory or trophic influences, it may act either tonically or phasically, and can bind to either ionotropic or metabotropic receptors that may be localized pre- and postsynaptically. This flexibility, combined with the diversity of GABA co-transmitters, neural circuit architectures and co-release mechanisms suggest it is unlikely that GABA co-transmission serves a single, universal function. Here, we propose some interesting possible functions of GABA co-release in synaptic transmission that we hope will stimulate further investigation. We note that in addition to the possible roles discussed below, GABA co-release might have a role in the developing and diseased CNS in regulating the neurotransmitter cycle3, the specification of neurotransmitters44, 45, and the functional establishment and reorganization of synapses (see REFs 4, 51–53).

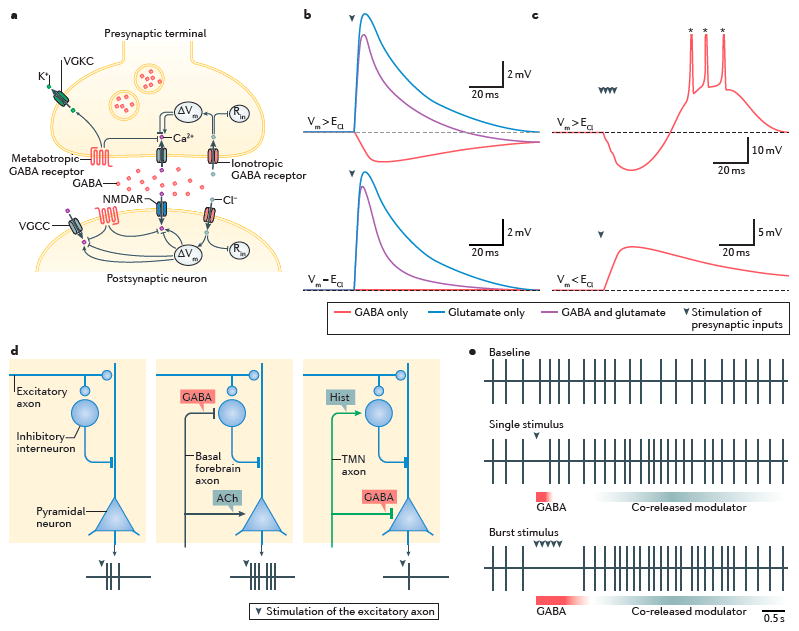

Inhibition

A major function of GABAergic signaling is the inhibition of activity in target neurons by decreasing exocytosis, hyperpolarizing membranes and shunting depolarization54–56 (FIG. 2a, FIG. 2b). When paired with excitatory or modulatory co-transmitters, GABA co-release may provide a faster and more targeted form of inhibition than that resulting from typical disynaptic mechanisms. For instance, in the LHb, a region lacking local interneurons, GABA co-release may act to balance glutamatergic excitation from EP11 and VTA12, and possibly providing a form of gain control to the LHb that in other brain areas arises from feed-forward recruitment of fast-spiking interneurons.

Figure 2. Functions of GABA co-release.

a|Once released in the synaptic cleft, GABA can signal pre- and postsynaptically, homo- and heterosynaptically and via ionotropic GABA receptors type A (GABAA) and GABA receptor type C (GABAC) and metabotropic GABAB receptors. Gating of GABAA and GABAC receptors shunts synaptic conductances by decreasing input resistance (Rin). Net flow of Cl− through these receptors alters the membrane potential (Vm), which affects Ca2+ influx through voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCCs) and NMDA receptors. GABAB receptors act to inhibit presynaptic exocytosis and postsynaptic depolarization through modulation of voltage gated potassium channels (VGKCs), VGCCs and the presynaptic release machinery. b|Depending on the Cl− reversal potential (ECl) relative to the resting membrane potential (Vrest) of a neuron, GABA co-release may dampen cellular excitability by physically hyperpolarizing postsynaptic membranes (top) or by shunting synaptic depolarizations (bottom). To illustrate this, the postsynaptic potentials evoked by presynaptic release of glutamate only, GABA only and co-release of glutamate and GABA are depicted. c|GABA release can exert a depolarizing influence if the post-synaptic cell expresses hyperpolarization-activated channels that depolarize membranes (top) or if intracellular Cl− is elevated, such that ECl lies above Vrest (bottom). Each example depicts fluctuations in membrane potential upon stimulation of a presynaptic GABAergic synapse (asterisk denotes truncated action potential). d|Co-transmission can be directed in space to achieve synergistic effects in complex neuronal circuits. Three cortical microcircuits are shown under different conditions, each composed of a pyramidal neuron, a local inhibitory interneuron and an excitatory afferent. Under baseline conditions (left), excitatory afferent stimulation evokes three spikes in the pyramidal cell. Target-specific co-release of GABA at some synapses, but not others, enables basal forebrain neurons to enhance (middle) and TMN neurons to dampen (right) the output of pyramidal cells. e|GABA co-release provides a temporally precise signal. Schematic representation of the spontaneous action potential discharge of a target cell under baseline conditions (top), or upon stimulation of afferents that co-release GABA along with a neuromodulator that increases membrane excitability by activating GPCRs (middle and bottom). Phasic inhibition of action potential firing by GABA co-release (the phasic inhibitory influence shown in blue) allows the postsynaptic cell to readily distinguish between single and burst stimulation of presynaptic afferents.

What function might the co-release of two inhibitory transmitters, such as GABA and glycine (which both gate Cl− conductances) serve? Glycinergic currents are considerably shorter than GABAergic currents, and are accelerated by GABA57. Co-transmission of two inhibitory neurotransmitters may therefore allow fine-tuning of the magnitude and duration of synaptic inhibition. Because metabotropic receptors for glycine have not been identified in mammals, co-release of GABA also confers on glycinergic synapses the ability to modulate transmission in a homo- and heterosynaptic manner, via metabotropic GABAB receptors58.

Providing a depolarizing influence

GABA can evoke action potentials in target neurons if intracellular Cl− is elevated, or if the target neurons express ion channels that promote rebound excitation (FIG. 2c). In mature neurons, the Cl− equilibrium potential (ECl) is typically below the spike threshold, precluding GABA from directly evoking firing. However, it is not uncommon for ECl to lie above the resting membrane potential of a neuron. In such cases, activation of GABAA receptors would cause a subthreshold membrane depolarization, with important consequences for somatic excitability and the induction of synaptic plasticity53. Co-release of GABA along with excitatory or modulatory transmitters may therefore enable synaptic partners with the flexibility to fine-tune the membrane potential of target cells so as to optimize the ionotropic or metabotropic actions of co-transmitters.

Providing a spatially targeted signal

GABA co-transmission, where it does occur, is not necessarily uniform across all synapses, either because presynaptic neurons restricts GABA release to particular sites, or because some postsynaptic targets do not express GABA receptors. Thus, rather than broadcasting the same information to all of the postsynaptic targets of a presynaptic neuron[AU:OK?], GABA co-transmission may serve several synergistic functions in complex circuits (FIG. 2d). For example, the fact that some terminals of individual SACs predominantly release ACh, whereas others within the same cell release both ACh and GABA, enables downstream DSGCs to encode both motion sensitivity and direction selectivity15. As another example, in cortex, coincident ACh-mediated excitation of layer I disinhibitory interneurons and GABA-mediated inhibition of deeper layer interneurons may account for the role of basal forebrain neurons in arousal59. Similarly, TMN neurons may increase cortical inhibitory synaptic transmission via the release of histamine, while simultaneously providing slow and sustained GABAergic inhibition to pyramidal neurons47.

GABAergic co-transmission might be further restricted to distinct subcellular regions of a target neuron, enabling fine spatial control of presynaptic release and postsynaptic activity. This may be particularly important for co-transmitter systems that signal by volume transmission. Midbrain dopaminergic neurons, for example, form synapses on dendritic spines that receive glutamatergic inputs60—because dopamine signals in a diffuse manner, GABA co-release may act to specifically shunt excitatory potentials within individual spines.

Providing a temporally precise signal

Monoamines signal almost exclusively through GPCRs. Their synaptic effects are therefore achieved over hundreds of milliseconds to minutes, significantly slower than those of transmitters acting on ionotropic receptors. Therefore in monoaminergic neurons, GABA co-release may provide the means to rapidly convey signals time-locked to sensory or motor events (FIG. 2e). SNc and VTA neurons fire tonically and modulate their discharge in response to salient stimuli by adding or omitting a few spikes. GABA co-release might play an important role in communicating these phasic changes in firing to striatal neurons. Interestingly, worms and insects have evolved Cl− channels gated by biogenic amines in addition to metabotropic receptors61–63, suggesting an important role for coincident fast inhibitory and slow modulatory signaling by aminergic cells.

Regulation of synaptic plasticity

By directly and indirectly influencing axonal and dendritic Ca2+ influx (FIG. 2a), GABAergic signaling plays an important role in the induction of short- and long-term synaptic plasticity at GABAergic and non-GABAergic synapses54, 55. Like any mild depolarization, subthreshold GABAA-mediated depolarization might favor Ca2+ influx and synaptic plasticity by reducing the efficacy of NMDA-type glutamate receptor Mg2+ block and increasing the opening probability of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCCs)64–66, while simultaneously dampening excitatory potentials via shunting inhibition. These mechanisms would be predicted to facilitate the induction of long-term potentiation, although such an effect not yet been demonstrated for GABA. Conversely, activation of GABAB receptors, often localized at excitatory postsynaptic terminals, can reduce Ca2+ influx through NMDA receptors and VGCCs by a variety of mechanisms54, 67–69, which would limit the induction of synaptic plasticity. Thus, GABA co-release could be a complementary signal to the metabotropic actions of transmitters such as ACh, dopamine and histamine in modulating the plasticity of synapses and neuronal circuits.

Conclusions

It has long been appreciated that individual neurons have the capacity to express and release multiple small molecule, peptide and gaseous transmitters1, 2. However, the notion that the primary synaptic actions of many neurons in the adult CNS are not limited to the release of a single classical transmitter has only recently been widely recognized3, 4. Rather than representing an evolutionary oversight, it is likely that co-release of multiple classical transmitters has emerged because of its ability to provide additional means of modulating and fine-tuning synaptic transmission between individual synaptic partners over many different time scales. As discussed in this article, there is now compelling functional evidence that GABAergic transmission can occur from neurons that also release glycine, glutamate, ACh and monoamines in the adult CNS. Many of the functions of GABA co-release remain to be determined, but the diversity and flexibility of GABAergic signaling are likely to factor greatly in the prevalence of GABA as a co-transmitter.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge members of the Sabatini lab for insightful discussions on this and other topics, and for fostering a learned and collegial research environment, which greatly helped shape this manuscript.

Biographies

Nicolas X. Tritsch obtained his Ph.D. in Neuroscience from Johns Hopkins University under the mentorship of Dr. Dwight Bergles. He recently completed a postdoctoral fellowship with Dr. Bernardo Sabatini at Harvard Medical School, and is currently an Assistant Professor and Leon Levy Neuroscience Fellow at New York University Langone Medical Center. His research focuses on understanding how synaptic communication within the basal ganglia shapes the execution of voluntary movements in health and disease. Lab website: http://www.med.nyu.edu/biosketch/tritsn01

Adam J. Granger studied Biology and Mathematics at Kalamazoo College, where he graduated in 2003. Following college, he joined the laboratory of Dr. Roger Nicoll at University of California San Francisco, where his Ph.D. thesis work focused on the molecular mechanisms of AMPA receptor trafficking during synaptic plasticity. He is now a postdoctoral fellow in the laboratory of Dr. Bernardo Sabatini at Harvard Medical School, where he studies neuromodulation and neural circuitry.

Bernardo L. Sabatini received an MD/PhD from Harvard Medical School in 1999 having done his thesis work with Dr. Wade Regher. After a postdoctoral fellowship with Dr. Karel Svoboda at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, he joined the faculty in the Department of Neurobiology at Harvard Medical School in 2001. He is currently a Professor of Neurobiology and an HHMI Investigator. Lab website: http://sabatini.hms.harvard.edu

Footnotes

Competing interests statement

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Burnstock G. Cotransmission. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2004;4:47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nusbaum MP, Blitz DM, Swensen AM, Wood D, Marder E. The roles of co-transmission in neural network modulation. Trends Neurosci. 2001;24:146–54. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01723-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hnasko TS, Edwards RH. Neurotransmitter corelease: mechanism and physiological role. Annu Rev Physiol. 2011;74:225–43. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-020911-153315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vaaga CE, Borisovska M, Westbrook GL. Dual-transmitter neurons: functional implications of co-release and co-transmission. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2014;29:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2014.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wojcik SM, et al. A shared vesicular carrier allows synaptic corelease of GABA and glycine. Neuron. 2006;50:575–87. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mathews GC, Diamond JS. Neuronal glutamate uptake Contributes to GABA synthesis and inhibitory synaptic strength. J Neurosci. 2003;23:2040–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-06-02040.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang L, Tu P, Bonet L, Aubrey KR, Supplisson S. Cytosolic transmitter concentration regulates vesicle cycling at hippocampal GABAergic terminals. Neuron. 2013;80:143–58. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Apostolides PF, Trussell LO. Rapid, activity-independent turnover of vesicular transmitter content at a mixed glycine/GABA synapse. J Neurosci. 2013;33:4768–81. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5555-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Awatramani GB, Turecek R, Trussell LO. Staggered development of GABAergic and glycinergic transmission in the MNTB. J Neurophysiol. 2005;93:819–28. doi: 10.1152/jn.00798.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dugue GP, Dumoulin A, Triller A, Dieudonne S. Target-dependent use of co-released inhibitory transmitters at central synapses. J Neurosci. 2005;25:6490–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1500-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shabel SJ, Proulx CD, Piriz J, Malinow R. Mood regulation. GABA/glutamate co-release controls habenula output and is modified by antidepressant treatment. Science. 2014;345:1494–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1250469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Root DH, et al. Single rodent mesohabenular axons release glutamate and GABA. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17:1543–51. doi: 10.1038/nn.3823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Proulx CD, Hikosaka O, Malinow R. Reward processing by the lateral habenula in normal and depressive behaviors. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17:1146–52. doi: 10.1038/nn.3779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Granger AJ, Mulder N, Saunders A, Sabatini BL. Cotransmission of acetylcholine and GABA. Neuropharmacology. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.07.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee S, Kim K, Zhou ZJ. Role of ACh-GABA cotransmission in detecting image motion and motion direction. Neuron. 2010;68:1159–72. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.11.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wei W, Hamby AM, Zhou K, Feller MB. Development of asymmetric inhibition underlying direction selectivity in the retina. Nature. 2011;469:402–6. doi: 10.1038/nature09600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morrie RD, Feller MB. An Asymmetric Increase in Inhibitory Synapse Number Underlies the Development of a Direction Selective Circuit in the Retina. J Neurosci. 2015;35:9281–6. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0670-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saunders A, Granger AJ, Sabatini BL. Corelease of acetylcholine and GABA from cholinergic forebrain neurons. Elife. 2015;4 doi: 10.7554/eLife.06412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saunders A, et al. A direct GABAergic output from the basal ganglia to frontal cortex. Nature. 2015;521:85–9. doi: 10.1038/nature14179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bjorklund A, Dunnett SB. Dopamine neuron systems in the brain: an update. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:194–202. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li X, Qi J, Yamaguchi T, Wang HL, Morales M. Heterogeneous composition of dopamine neurons of the rat A10 region: molecular evidence for diverse signaling properties. Brain Struct Funct. 2013;218:1159–76. doi: 10.1007/s00429-012-0452-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xenias HS, Ibanez-Sandoval O, Koos T, Tepper JM. Are striatal tyrosine hydroxylase interneurons dopaminergic? J Neurosci. 2015;35:6584–99. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0195-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lammel S, et al. Diversity of transgenic mouse models for selective targeting of midbrain dopamine neurons. Neuron. 2015;85:429–38. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.12.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pupe S, Wallen-Mackenzie A. Cre-driven optogenetics in the heterogeneous genetic panorama of the VTA. Trends Neurosci. 2015;38:375–86. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maher BJ, Westbrook GL. Co-transmission of dopamine and GABA in periglomerular cells. J Neurophysiol. 2008;99:1559–64. doi: 10.1152/jn.00636.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Borisovska M, Bensen AL, Chong G, Westbrook GL. Distinct modes of dopamine and GABA release in a dual transmitter neuron. J Neurosci. 2013;33:1790–6. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4342-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hirasawa H, Betensky RA, Raviola E. Corelease of dopamine and GABA by a retinal dopaminergic neuron. J Neurosci. 2012;32:13281–91. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2213-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu S, Plachez C, Shao Z, Puche A, Shipley MT. Olfactory bulb short axon cell release of GABA and dopamine produces a temporally biphasic inhibition-excitation response in external tufted cells. J Neurosci. 2013;33:2916–26. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3607-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tritsch NX, Ding JB, Sabatini BL. Dopaminergic neurons inhibit striatal output through non-canonical release of GABA. Nature. 2012;490:262–6. doi: 10.1038/nature11466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tritsch NX, Oh WJ, Gu C, Sabatini BL. Midbrain dopamine neurons sustain inhibitory transmission using plasma membrane uptake of GABA, not synthesis. Elife. 2014;3:e01936. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kress GJ, et al. Fast phasic release properties of dopamine studied with a channel biosensor. J Neurosci. 2014;34:11792–802. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2355-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hedou G, et al. Immunohistochemical studies of the localization of neurons containing the enzyme that synthesizes dopamine, GABA, or gamma-hydroxybutyrate in the rat substantia nigra and striatum. J Comp Neurol. 2000;426:549–60. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20001030)426:4<549::aid-cne4>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Poulin JF, et al. Defining midbrain dopaminergic neuron diversity by single-cell gene expression profiling. Cell Rep. 2014;9:930–43. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yelin R, Schuldiner S. The pharmacological profile of the vesicular monoamine transporter resembles that of multidrug transporters. FEBS Lett. 1995;377:201–7. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01346-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stensrud MJ, Puchades M, Gundersen V. GABA is localized in dopaminergic synaptic vesicles in the rodent striatum. Brain Struct Funct. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s00429-013-0609-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karayannis T, et al. Cntnap4 differentially contributes to GABAergic and dopaminergic synaptic transmission. Nature. 2014;511:236–40. doi: 10.1038/nature13248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scimemi A. Structure, function, and plasticity of GABA transporters. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014;8:161. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Straub C, Tritsch NX, Hagan NA, Gu C, Sabatini BL. Multiphasic modulation of cholinergic interneurons by nigrostriatal afferents. J Neurosci. 2014;34:8557–69. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0589-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guo Q, et al. Whole-brain mapping of inputs to projection neurons and cholinergic interneurons in the dorsal striatum. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0123381. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim JI, et al. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1a1 mediates a GABA synthesis pathway in midbrain dopaminergic neurons. Science. 2015;350:102–6. doi: 10.1126/science.aac4690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gainetdinov RR, Caron MG. Monoamine transporters: from genes to behavior. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2003;43:261–84. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.43.050802.112309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barreiro-Iglesias A, Villar-Cervino V, Anadon R, Rodicio MC. Dopamine and gamma-aminobutyric acid are colocalized in restricted groups of neurons in the sea lamprey brain: insights into the early evolution of neurotransmitter colocalization in vertebrates. J Anat. 2009;215:601–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2009.01159.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Svensson E, Proekt A, Jing J, Weiss KR. PKC-mediated GABAergic enhancement of dopaminergic responses: implication for short-term potentiation at a dual-transmitter synapse. J Neurophysiol. 2014;112:22–9. doi: 10.1152/jn.00794.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Velazquez-Ulloa NA, Spitzer NC, Dulcis D. Contexts for dopamine specification by calcium spike activity in the CNS. J Neurosci. 2011;31:78–88. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3542-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dulcis D, Jamshidi P, Leutgeb S, Spitzer NC. Neurotransmitter switching in the adult brain regulates behavior. Science. 2013;340:449–53. doi: 10.1126/science.1234152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haas HL, Sergeeva OA, Selbach O. Histamine in the nervous system. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:1183–241. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00043.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yu X, et al. Wakefulness Is Governed by GABA and Histamine Cotransmission. Neuron. 2015;87:164–78. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hatton GI, Yang QZ. Ionotropic histamine receptors and H2 receptors modulate supraoptic oxytocin neuronal excitability and dye coupling. J Neurosci. 2001;21:2974–82. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-09-02974.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Williams RH, et al. Optogenetic-mediated release of histamine reveals distal and autoregulatory mechanisms for controlling arousal. J Neurosci. 2014;34:6023–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4838-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kukko-Lukjanov TK, Panula P. Subcellular distribution of histamine, GABA and galanin in tuberomamillary neurons in vitro. J Chem Neuroanat. 2003;25:279–92. doi: 10.1016/s0891-0618(03)00043-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Owens DF, Kriegstein AR. Is there more to GABA than synaptic inhibition? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:715–27. doi: 10.1038/nrn919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Le Magueresse C, Monyer H. GABAergic interneurons shape the functional maturation of the cortex. Neuron. 2013;77:388–405. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kesner P, Gobert D, Ruthazer ES. Formula for Unsilencing Plasticity: Spike with GABA. Neuron. 2015;87:915–7. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chalifoux JR, Carter AG. GABAB receptor modulation of synaptic function. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2011;21:339–44. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Higley MJ. Localized GABAergic inhibition of dendritic Ca(2+) signalling. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014;15:567–72. doi: 10.1038/nrn3803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Isaacson JS, Scanziani M. How inhibition shapes cortical activity. Neuron. 2011;72:231–43. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lu T, Rubio ME, Trussell LO. Glycinergic transmission shaped by the corelease of GABA in a mammalian auditory synapse. Neuron. 2008;57:524–35. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Magnusson AK, Park TJ, Pecka M, Grothe B, Koch U. Retrograde GABA signaling adjusts sound localization by balancing excitation and inhibition in the brainstem. Neuron. 2008;59:125–37. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fu Y, et al. A cortical circuit for gain control by behavioral state. Cell. 2014;156:1139–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Moss J, Bolam JP. In: Dopamine Handbook. Iversen LL, editor. Oxford University Press; 2010. pp. 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zheng Y, et al. Identification of two novel Drosophila melanogaster histamine-gated chloride channel subunits expressed in the eye. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:2000–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107635200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gengs C, et al. The target of Drosophila photoreceptor synaptic transmission is a histamine-gated chloride channel encoded by ort (hclA) J Biol Chem. 2002;277:42113–20. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207133200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ringstad N, Abe N, Horvitz HR. Ligand-gated chloride channels are receptors for biogenic amines in C. elegans. Science. 2009;325:96–100. doi: 10.1126/science.1169243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jahr CE, Stevens CF. Voltage dependence of NMDA-activated macroscopic conductances predicted by single-channel kinetics. J Neurosci. 1990;10:3178–82. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-09-03178.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Magee JC, Johnston D. Synaptic activation of voltage-gated channels in the dendrites of hippocampal pyramidal neurons. Science. 1995;268:301–4. doi: 10.1126/science.7716525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Carter AG, Sabatini BL. State-dependent calcium signaling in dendritic spines of striatal medium spiny neurons. Neuron. 2004;44:483–93. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sabatini BL, Svoboda K. Analysis of calcium channels in single spines using optical fluctuation analysis. Nature. 2000;408:589–93. doi: 10.1038/35046076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Skeberdis VA, et al. Protein kinase A regulates calcium permeability of NMDA receptors. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:501–10. doi: 10.1038/nn1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lur G, Higley MJ. Glutamate Receptor Modulation Is Restricted to Synaptic Microdomains. Cell Rep. 2015;12:326–34. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Strata P, Harvey R. Dale’s principle. Brain Res Bull. 1999;50:349–50. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(99)00100-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang S, et al. Dopaminergic and glutamatergic microdomains in a subset of rodent mesoaccumbens axons. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:386–92. doi: 10.1038/nn.3945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]