SUMMARY

Telomeres are essential for chromosomal stability and markers of biological age. We evaluated the effect of pre-transplant short (<10th percentile-for-age) or very short (<5th or <1st percentile-for-age) leucocyte telomere length on survival after unrelated donor haematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) for acquired severe aplastic anaemia (SAA). Patient pre-transplant blood samples and clinical data were available at the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research. We used quantitative real time polymerase chain reaction to measure relative telomere length (RTL) in 490 SAA patients who received HCT between 1990 and 2013 (median age=20 years). One hundred and twelve patients (22.86%) had pre-HCT RTL<10th percentile-for-age, with the majority below the 5th percentile (N=80, 71.43%). RTL<10th percentile-for-age was associated with a higher risk of post-HCT mortality (hazard ratio [HR]=1.78, 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.18–2.69, p=0.006) compared with RTL≥50th percentile; no survival differences were noted in longer RTL categories (p>0.10). Time-dependent effects for post-HCT mortality were only observed in relation to very short RTL; HR comparing RTL<5th vs. ≥5th percentile=1.38, p=0.15 for the first 12 months after HCT, and HR=3.91, p<0.0001, thereafter, p-heterogeneity=0.008).; the corresponding HRs for RTL<1st vs. ≥1st percentile=1.29, p=0.41, and HR=5.18, p<0.0001, p-heterogeneity=0.005). The study suggests a potential role for telomere length in risk stratification of SAA patients in regard to their HCT survival.

Keywords: Severe aplastic anaemia, telomere lengths, haematopoietic cell transplantation, unrelated donor, survival

INTRODUCTION

Severe aplastic anaemia (SAA) is a rare, complex bone marrow failure disorder that may present at any age. The disease is predominantly acquired, immune-mediated and triggered by certain environmental exposures in some cases (Young 2013). Acquired SAA often responds to immunosuppressive therapy and produces durable remissions in many patients. Allogeneic haematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) is a curative option for SAA; it is the frontline therapy in young patients with a well-matched sibling donor, and second-line for all other patients after failing immunosuppressive therapy (Bacigalupo 2017).

Telomeres, the nucleoprotein complexes at the chromosome ends that are critical for chromosomal stability, shorten with each cell division and are associated with aging-related diseases (Aviv and Shay 2018). Patients with the telomere biology disorder (TBD) dyskeratosis congenita (DC) have very short telomeres, usually below the 1st percentile-for-age as measured in leucocyte subsets by flow cytometry with in situ hybridisation (flow FISH) (Alter, et al 2007, Alter, et al 2015). DC and its related TBDs are caused by the inheritance of germline mutations in one of several telomere-biology genes including DKC1, TERC, TERT, TINF2, NOP10, NHP2, CTC1, WRAP53, RTEL1, ACD, STN1, NAF1 or PARN genes (Bertuch 2015, Savage and Dufour 2017). HCT outcome studies in patients with DC show a high risk of early transplant-related mortality with myeloablative conditioning regimens and late mortality due to long-term DC-related complications (Gadalla, et al 2013). Short telomere length (TL) in patients with acquired aplastic anaemia are associated with a high risk of relapse, clonal evolution, and mortality, but the association between pre-HCT TL and patient outcome after HCT in acquired SAA is still not clear (Scheinberg, et al 2010). Our previous report of 330 patients with marrow failure (235 had acquired SAA) showed that having long pre-HCT TL was not associated with survival benefit after unrelated donor HCT (5-year survival=47% vs. 46% for those with the longest tertile vs. shorter TL) (Gadalla, et al 2015).

In the current study of 490 patients (177 were included in the original report, Gadalla et al 2015) who received unrelated donor HCT for an apparently acquired SAA, we used quantitative real time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) assay to measure relative telomere length (RTL). We categorized RTL based on age percentiles in healthy donors, and evaluated the effect of short RTL (<10th percentile-for-age) on post-HCT survival in patients with SAA who received unrelated donor HCT.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and clinical data source

Patients with SAA in this study were identified from the Center of International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) database as part of the National Cancer Institute (NCI)-CIBMTR Transplant Outcomes in Aplastic Anemia (TOAA) study; details are available elsewhere (Gadalla, et al 2016a). CIBMTR, a research collaboration between the National Marrow Donor Program (NMDP) and the Medical College of Wisconsin, provides one of the world’s largest databases and biorepositories for HCT-related research (details are available at: https://www.cibmtr.org/About/Impact/Pages/index.aspx).

The current study included 490 patients with SAA who received an unrelated donor blood or marrow transplant with high-resolution human leucocyte antigen (HLA) typing between 1990 and 2013, and had pre-HCT DNA available for TL measurement. Patients with a clinical diagnosis of an inherited bone marrow failure syndrome were excluded from the analysis. Blood samples were collected before HCT, with median time between blood collection and HCT of 7 days.

The study was approved by the NMDP institutional review board and the National Institutes of Health Office of Human Subjects Research Protections. All patients or their parents provided informed consent.

Telomere length measurement

We extracted DNA from patient pre-HCT peripheral blood mononuclear cells or whole blood using the QIAamp Maxi Kit procedure (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA). TL was measured by monoplex qPCR at the NCI Cancer Genomics Research laboratory after adapting published methods,(Callicott and Womack 2006, Cawthon 2002) as described previously (Gadalla, et al 2016a). Briefly, relative telomere length (RTL) was calculated as the ratio of telomere (T) signal concentration to that of a single copy gene (RPLP0, also termed 36B4; S); raw measurements were then standardized using internal quality-controlled calibrator samples replicated within each plate. All telomeric and RPLP0/36B4 results were measured in triplicate and their average was used for all calculations. Final RTL values were log transformed to ensure normality. RTL for SAA patients and healthy donors were measured in two sets. The mean coefficient of variations (CV) for telomeric measures (T) was 0.45%, and for single copy gene (RPLP0/36B4) was 0.4% in all samples, and 5.23% for the standardized T/S measurement from replicate samples. Laboratory personnel were blinded to patient characteristics and outcomes.

Calculation of age-adjusted telomere length

RTL was age-standardized using z-scores calculated as follows:

Expected RTL and RMSE were calculated based on the RTL set-specific linear regression model of log RTL and age from 705 healthy HCT donors for whom RTL was measured simultaneously with that of patients included in this analysis. Z-scores were then transformed to percentiles-for-age using “probnorm” function in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). The distribution of RTL percentile-for-age is shown in Figure S1. Short RTL was defined as <10th percentile-for-age and very short RTL was defined as <5th or 1st percentile-for-age.

Statistical analysis

For survival analysis, we used the Kaplan-Meier estimator to calculate the probability of overall survival (OS) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The log-rank test was used to compare the survival distribution across groups. Follow-up time started at the date of HCT and ended at death or was censored at date of last follow-up or end of study on 30 August 2017.

For multivariable analysis, we used Cox proportional hazard models to compare different categories of RTL. The Schoenfeld residuals method was used to evaluate the proportional hazard assumption in relation to RTL categories. Assumption violation was noted in analyses of very short RTL (<5th or 1st percentile) compared with longer RTL categories; no violation in analysis of RTL <10th percentile-for-age. Therefore, we conducted a time-dependent analysis to evaluate the effect of very short RTL on early versus late mortality after HCT. The post-HCT cut-off time point was determined based on the comparison of model fit statistics from different time points, using the Akaike Information Criterion. Selection of clinical factors included in the final model was based on a stepwise procedure with p=0.25 for model entry and 0.15 for retention. All final models were adjusted for patient age, donor age, year at HCT, Karnofsky performance score (KPS), intensity of conditioning regimen and level of HLA matching; all met the proportional hazards assumption. To address the possibility of confounding related to previous number of cycles of immunosuppression used, we adjusted all models for time from diagnosis to HCT, as a proxy. In a secondary analysis, we tested an interaction between year of HCT (1990–2005 and 2006–2013) and RTL categories to evaluate possible changes in observed associations with changes in transplant practices across the years.

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R package ‘survminer’ (https://cran.r-project.org/package=survminer).

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

The median age at HCT was 20 years (range ≤1–77 years). The majority of patients were Caucasian (N=379, 77.3%), received a bone marrow graft (N=393, 80.2%), and had an 8/8 HLA matched donor (N=304, 62.0%). Less than half of the patients received myeloablative regimens (N=214, 43.7%). The median follow-up was 3 years (range ≤1 months-24.4 years).

Approximately one-fifth of the patients (N=112, 22.9%) had pre-HCT RTL <10th percentile-for-age (median age=18.7 years). Of them, the majority had RTL<5th percentile (N=80, 71.4%) and 44 patients (39.3%) had RTL <1st percentile-for-age. No statistically significant differences were noted in patient characteristics or transplant modality-related factors by RTL group, except for a longer time from diagnosis to transplant noted in patients with RTL <10th percentile-for-age (p=0.008) (Table I).

Table I.

Patients characteristics by categories of age-standardized relative telomere length

| Relative telomere lengths percentile-for-age, N (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <10th (N=112) |

≥10th (N=378) |

p1 | |||

| Patient-related | |||||

| Recipient age at transplant (years) | 0.18 | ||||

| ≤10 | 19 | (17.0%) | 73 | (19.3%) | |

| >10, ≤20 | 39 | (34.8%) | 109 | (28.8%) | |

| >20, ≤40 | 40 | (35.7%) | 118 | (31.2%) | |

| >40 | 14 | (12.5%) | 78 | (20.6%) | |

| Recipient sex | 0.09 | ||||

| Male | 68 | (60.7%) | 195 | (51.6%) | |

| Female | 44 | (39.3%) | 183 | (48.4%) | |

| Recipient race | 0.72 | ||||

| Caucasian | 88 | (78.6%) | 291 | (77.0%) | |

| Other | 24 | (21.4%) | 87 | (23.0%) | |

| Karnofsky Performance Score2 | 0.84 | ||||

| 10–80 | 26 | (23.4%) | 88 | (24.4%) | |

| 90–100 | 85 | (76.6%) | 273 | (75.6%) | |

| Transplant-related | |||||

| Graft type | 0.62 | ||||

| Bone marrow | 88 | (78.6%) | 305 | (80.7%) | |

| PBSC | 24 | (21.4%) | 73 | (19.3%) | |

| Donor/recipient sex match | 0.30 | ||||

| Donor male/recipient male | 50 | (44.6%) | 144 | (38.1%) | |

| Donor male/recipient female | 31 | (27.7%) | 113 | (29.9%) | |

| Donor female/recipient male | 18 | (16.1%) | 52 | (13.8%) | |

| Donor female/recipient female | 13 | (11.6%) | 69 | (18.3%) | |

| Donor/recipient CMV serostatus match2 | 0.20 | ||||

| Donor negative/recipient negative | 36 | (33.0%) | 102 | (28.4%) | |

| Donor negative/recipient positive | 36 | (33.0%) | 106 | (29.5%) | |

| Donor positive/recipient negative | 8 | (7.3%) | 54 | (15.0%) | |

| Donor positive/recipient positive | 29 | (26.6%) | 97 | (27.0%) | |

| Conditioning regimen | 0.07 | ||||

| Myeloablative | 41 | (36.6%) | 173 | (45.8%) | |

| RIC/Non-myeloablative | 40 | (35.7%) | 136 | (36.0%) | |

| Other | 31 | (27.7%) | 69 | (18.3%) | |

| GVHD Prophylaxis | 0.983 | ||||

| Tacrolimus-based | 46 | (41.1%) | 160 | (42.3%) | |

| CSA-based | 53 | (47.3%) | 175 | (46.3%) | |

| Other | 12 | (10.7%) | 39 | (10.3%) | |

| No GVHD prophylaxis | 1 | (0.9%) | 4 | (1.1%) | |

| HLA match2 | 0.46 | ||||

| 8/8 | 69 | (62.2%) | 235 | (66.0%) | |

| ≤7/8 | 42 | (37.8%) | 121 | (34.0%) | |

| Time from diagnosis to HCT (months)2 | |||||

| <12 months | 43 | (39.1%) | 188 | (50.1%) | 0.008 |

| 12-<24 months | 21 | (19.1%) | 88 | (23.5%) | |

| 24≤ months | 46 | (41.8%) | 99 | (26.4%) | |

| Year of transplant | 0.22 | ||||

| 1990–2005 | 35 | (31.2%) | 142 | (37.5%) | |

| 2006–2013 | 77 | (68.8%) | 236 | (62.4%) | |

Chi-square test unless otherwise specified

Count does not add to the total number due to missing values

Fisher’s exact test

CMV: cytomegalovirus; CSA: ciclosporin; GVHD: graft-versus-host disease; HCT: haematopoietic cell transplantation; HLA: human leucocyte antigen; PBSC: peripheral blood stem cells; RIC: reduced intensity chemotherapy

The effect of short and very short RTL on patient post-transplant survival

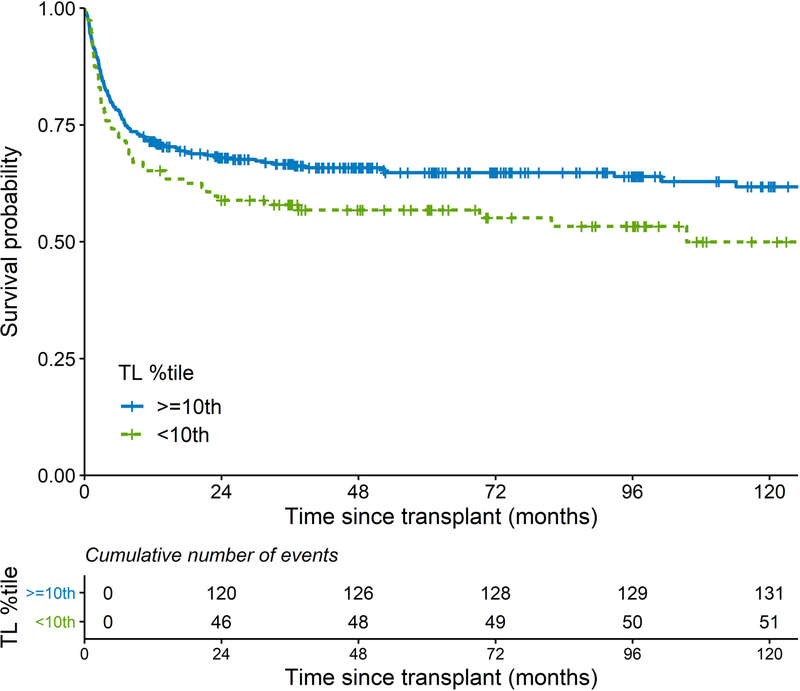

Short telomeres, defined as <10th percentile for-age, was associated with worse survival after unrelated donor HCT for SAA (p log-rank=0.03). The 5-year OS was 57% (95% CI=47–66%) vs. 65% (95% CI=60–70%) in the short vs. longer RTL, respectively. The 10-year OS was 50% (95% CI=39–61%) vs. 62% (95% CI=56–67%), respectively (Figure 1). The Kaplan Meier plots for post-HCT survival probabilities by the RTL of <1st, 1st-<5th, 5th-<10th, 10th-<25th, 25th-<50th, and ≥50th percentile-for-age are shown in Figure S2. These plots show poor post-HCT survival in patients with short RTL categories, particularly those with RTL <1st and 1-<5th RTL percentiles-for-age with a noticeable wider survival gap after the first year post-HCT. For patients with a RTL in the 5th-<10th percentile, all deaths (N=11) occurred in the first year post-HCT.

Figure 1:

Kaplan-Meier curves of post-transplant survival patients with severe aplastic anaemia comparing patients with relative telomere length < vs. ≥ 10th percentile-for-age.

TL: telomere length.

In multivariable analysis, patients with RTL <10th percentile were at excess risk of post-HCT mortality (HR=1.78, 95% CI=1.18–2.69, p=0.006) when compared with patients with RTL ≥50th percentile-for-age. No statistically significant survival differences were noted with RTL categories between the 10th and 50th percentile (HR=1.21, 95% CI=0.78–1.88, p=0.40 in those with RTL between 10th and <25th percentile, and HR=0.97, 95% CI=0.63–1.51, p=0.90 in those with RTL between 25th-<50th percentile) (Table II). In analyses comparing patients with RTL<10th percentile to all others, the HR was 1.68, 95% CI=1.20–2.37, p=0.003. Similar associations were found in the analysis of very short telomere lengths, with HR=1.80, 95% CI=1.25–2.60, p=0.002 for RTL<5th percentile and HR=1.90, 95% CI=1.18–3.07, p=0.009 for RTL<1st percentile-for-age (Table II). No statistically significant difference in the observed associations was noted by calendar time (p-interaction ≥0.1 for all models) (Table SI).

Table II.

Post-HCT mortality by categories of patient pre-HCT telomere abnormalities

| Events/total (n/N) | HR (95% CI)* | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RTL(percentiles-for-age) | ||||

| <10th | 52/109 | 1.78 (1.18–2.69) | 0.006 | |

| 10th–<25th | 39/96 | 1.21 (0.78–1.88) | 0.40 | |

| 25th–<50th | 34/97 | 0.97 (0.63–1.51) | 0.90 | |

| ≥50th | 52/160 | Reference | ||

| Categories of short RTL | ||||

| In short RTL | In longer RTL | |||

| <10th vs. ≥10th percentile-for-age | 52/109 | 125/353 | 1.68 (1.20–2.37) | 0.003 |

| <5th vs. ≥5th percentile-for-age | 41/77 | 136/385 | 1.80 (1.25–2.60) | 0.002 |

| <1st vs. ≥1st percentile-for-age | 21/42 | 156/420 | 1.90 (1.18–3.07) | 0.009 |

Hazard ratio and 95% confidence interval; Models were adjusted for patient age, donor age, Karnofsky score, conditioning intensity, year at HCT, HLA matching and time from diagnosis to HCT.

CI: confidence interval; HCT: haematopoietic cell transplantation; HLA: human leucocyte antigen; HR: hazard ratio; RTL: relative telomere length

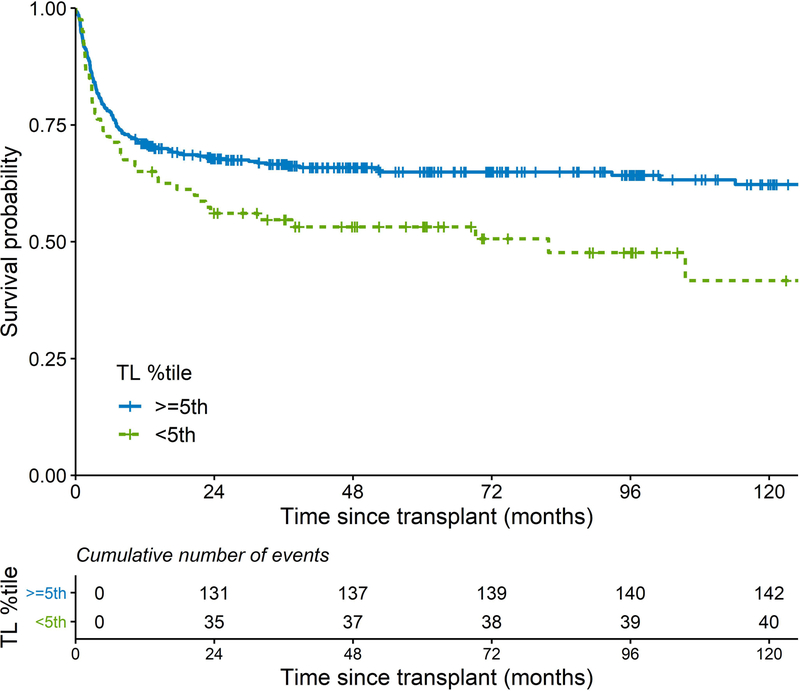

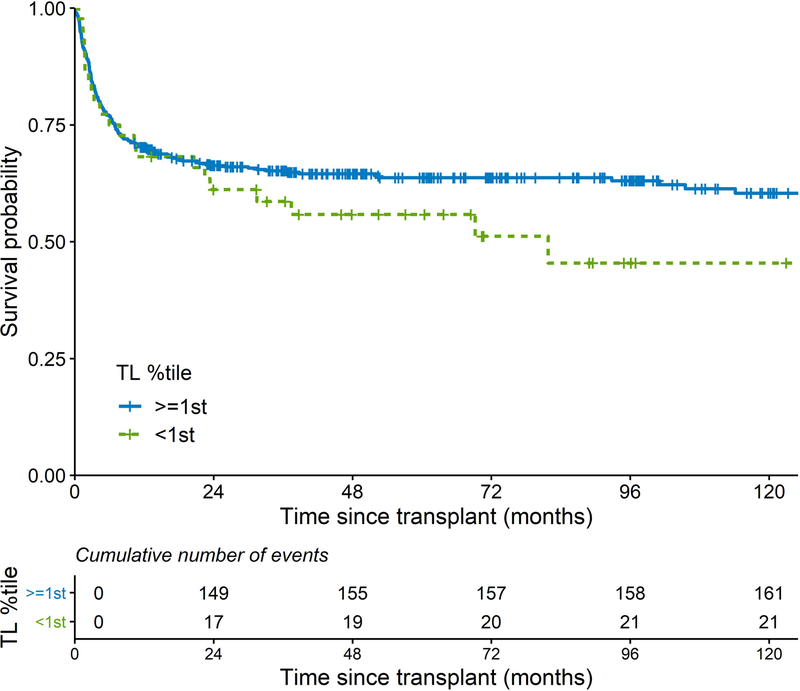

In a time-dependent analysis of very short RTL, the risk of post-HCT death in patients with RTL < 5th or <1st percentile, as compared to those with longer RTL, increased after the first 12 months of HCT (Figure 2 A, B). The HRs for death during the first 12 months after HCT were 1.38 and 1.29 (p>0.05), and HRs were 3.91 (p<0.0001) and 5.18 (p<0.0001) for RTL<5th and RTL<1st percentile, respectively, thereafter (Table III).

Figure 2:

Kaplan-Meier curves of post-transplant survival in patients with severe aplastic anaemia; comparing A) patients with relative telomere length < vs. ≥ 5th percentile-for-age; B) patients with relative telomere length < vs. ≥ 1st percentile-for-age.

TL: telomere length.

Table III.

Post-transplant mortality by time after HCT for patients with very short pre-HCT telomere length

| RTL (percentile-for-age) | Time since HCT | P heterogeneity | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≤ 12 months | > 12 months | ||

| HR (95% CI)* | |||

| <5th vs. ≥5th | 1.38 (0.89–2.13) | 3.91 (2.03–7.52) | 0.008 |

| <1st vs. ≥1st | 1.29 (0.70–2.38) | 5.18 (2.38–11.27) | 0.005 |

Hazard ratio and 95% confidence interval; Models were adjusted for patient age, donor age, Karnofsky score, conditioning intensity, year at HCT, HLA matching and time from diagnosis to HCT.

CI: confidence interval; HCT: haematopoietic cell transplantation; HLA: human leucocyte antigen; HR: hazard ratio; RTL: relative telomere length.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we showed that having a short RTL (<10th percentile-for-age) in pre-HCT recipient blood samples was associated with a high risk of post-transplant mortality in patients with severe aplastic anaemia. The mortality risk increased after the first 12 months in patients with very short RTL (<5th or 1st percentile-for-age).

The association between recipient pre-HCT telomere length and outcomes after HCT has been investigated in several studies. Our previous report in SAA showed an association between donor RTL and patient post-HCT survival, but no survival difference was noted when comparing patients with the longest tertile of pre-HCT RTL and those with shorter telomeres (Gadalla, et al 2015). Results from the current study do not necessarily conflict with the previous finding, as the survival disadvantage shown here was limited to patients with RTL <10th percentile-for age (compared with RTL >50th percentile, the HR for patients with RTL <10th percentile=1.78 vs. 1.21 in patients with RTL between 10th to <25th and 0.97 in patients with RTL between 25th to <50th percentile). The smaller sample size of the previous study, the use of tertiles to classify RTL, and combining the small number of patients with very short RTL to the majority of others with RTL in the 2nd and 3rd tertiles, and the inclusion of other marrow failure syndromes may explain the apparently different results. For malignant diseases, an association between short pre-transplant RTL and risk of transplant-related mortality has been reported but inconsistencies exist (Peffault de Latour, et al 2012, Wang, et al 2017, Xhaard, et al 2017)

The presence of very short telomeres in patients with SAA may indicate the presence of an unrecognized TBD, at least in some patients. Alternatively, short telomeres could be a consequence of impaired haematopoiesis in the absence of inherited telomere defect. Germline mutations in a limited number of telomere-biology genes (TERT, TERC, TINF2 or DKC1) have been reported in a small fraction (between 2–5%) of patients diagnosed with apparently acquired aplastic anaemia (Du, et al 2009, Vulliamy, et al 2005, Yamaguchi, et al 2003, Yamaguchi, et al 2005). A recent study of a hospital-based cohort of patients with TBD of all ages and different phenotypic presentations showed that that almost all patients had telomere length ≤10th percentile-for-age by the highly accurate flow FISH assay (Alder, et al 2018). The use of a cell-based assay for telomere length measurement, such as flow FISH, may provide some guidance, as telomere shortening in acquired SAA primarily affects granulocytes (Brummendorf, et al 2001), in contrast to shortening in all leucocyte subtypes and different tissues in the case of inherited telomere defects (Alter, et al 2015, Gadalla, et al 2010).

Our finding of higher mortality risks in the second post-transplant year and beyond in patients with very short telomeres (<5th or 1st percentile-for-age) is consistent with previous findings in patients with DC. A CIBMTR study of 34 patients with DC who received either matched sibling or unrelated donor HCT between 1981–2009 reported a 5-year survival of 57% and 10-year survival of 30% (Gadalla, et al 2013). Subsequent studies confirmed previous finding (Barbaro and Vedi 2016, Fioredda, et al 2018). Comparison of cause of death information reported to CIBMTR for patients with RTL <5th percentile showed that most first year deaths were caused by graft failure (17.9%), graft-versus-host disease (18%) and infections (17.9%) whereas the main causes of death beyond the first year were: organ failure (26.7%), cancer (20%) and infections (20%).

The study strengths include the large sample size, long post-transplant follow-up, availability of pre-transplant blood samples and comprehensive clinical information. Limitations include the unavailability of viable cells, which limited our ability to measure leucocyte cell-specific telomere length using flow FISH assays. The use of a qPCR assay for telomere length measurement may be limited by its suboptimal ability to detect very short telomeres (Gadalla, et al 2016b, Wang, et al 2018), a limitation that may result in an under-estimation of the true association. Also, the study lacked information on the number of cycles of immunosuppressive therapy used, which can result to residual confounding. To address this point, we adjusted all our models for time from diagnosis to HCT, as a proxy.

In conclusion, pre-HCT short telomere length is a prognostic factor for post-HCT survival in patients with SAA. It is possible that patients with very short telomere length before HCT act clinically like those with TBDs rather than those with idiopathic aplastic anaemia and may need to be managed accordingly. Our results also highlight the importance of long-term post-transplant follow-up for those patients.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The study was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute; by a Public Health Service grant (5U24CA076518) from the National Cancer Institute, the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, a Grant/Cooperative Agreement 4U10HL069294 from NHLBI and NCI; a contract from the Health Resources, and Services Administration (HHSH234200637015C); and by three Grants N00014-17-1-2388, N00014-16-1-2020 and N0014-17-1-2850 from the Office of Naval Research.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST / FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This manuscript is original and is not being considered for publication in any other peer-reviewed journal. The results will be presented at the 2019 Transplantation and Cellular Therapy meeting. The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

REFERNCES

- Alder JK, Hanumanthu VS, Strong MA, DeZern AE, Stanley SE, Takemoto CM, Danilova L, Applegate CD, Bolton SG, Mohr DW, Brodsky RA, Casella JF, Greider CW, Jackson JB & Armanios M (2018) Diagnostic utility of telomere length testing in a hospital-based setting. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 115, E2358–E2365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alter BP, Baerlocher GM, Savage SA, Chanock SJ, Weksler BB, Willner JP, Peters JA, Giri N & Lansdorp PM (2007) Very short telomere length by flow fluorescence in situ hybridization identifies patients with dyskeratosis congenita. Blood, 110, 1439–1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alter BP, Giri N, Savage SA & Rosenberg PS (2015) Telomere length in inherited bone marrow failure syndromes. Haematologica, 100, 49–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aviv A & Shay JW (2018) Reflections on telomere dynamics and ageing-related diseases in humans. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacigalupo A (2017) How I treat acquired aplastic anemia. Blood, 129, 1428–1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbaro P & Vedi A (2016) Survival after Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant in Patients with Dyskeratosis Congenita: Systematic Review of the Literature. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation, 22, 1152–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertuch AA (2015) The Molecular Genetics of the Telomere Biology Disorders. RNA Biology, 0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brummendorf TH, Rufer N, Holyoake TL, Maciejewski J, Barnett MJ, Eaves CJ, Eaves AC, Young N & Lansdorp PM (2001) Telomere length dynamics in normal individuals and in patients with hematopoietic stem cell-associated disorders. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 938, 293–303; discussion 303–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callicott RJ & Womack JE (2006) Real-time PCR assay for measurement of mouse telomeres. Comparative Medicine, 56, 17–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cawthon RM (2002) Telomere measurement by quantitative PCR. Nucleic Acids Research, 30, e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du HY, Mason PJ, Bessler M & Wilson DB (2009) TINF2 mutations in children with severe aplastic anemia. Pediatr.Blood Cancer, 52, 687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fioredda F, Iacobelli S, Korthof ET, Knol C, van Biezen A, Bresters D, Veys P, Yoshimi A, Fagioli F, Mats B, Zecca M, Faraci M, Miano M, Arcuri L, Maschan M, O’Brien T, Diaz MA, Sevilla J, Smith O, Peffault de Latour R, de la Fuente J, Or R, Van Lint MT, Tolar J, Aljurf M, Fisher A, Skorobogatova EV, Diaz de Heredia C, Risitano A, Dalle JH, Sedlacek P, Ghavamzadeh A & Dufour C (2018) Outcome of haematopoietic stem cell transplantation in dyskeratosis congenita. British Journal of Haematology, 183, 110–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadalla SM, Cawthon R, Giri N, Alter BP & Savage SA (2010) Telomere length in blood, buccal cells, and fibroblasts from patients with inherited bone marrow failure syndromes. Aging (Albany.NY), 2, 867–874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadalla SM, Sales-Bonfim C, Carreras J, Alter BP, Antin JH, Ayas M, Bodhi P, Davis J, Davies SM, Deconinck E, Deeg HJ, Duerst RE, Fasth A, Ghavamzadeh A, Giri N, Goldman FD, Kolb EA, Krance R, Kurtzberg J, Leung WH, Srivastava A, Or R, Richman CM, Rosenberg PS, Toledo Codina JS, Shenoy S, Socie G, Tolar J, Williams KM, Eapen M & Savage SA (2013) Outcomes of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in patients with dyskeratosis congenita. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation, 19, 1238–1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadalla SM, Wang T, Haagenson M, Spellman SR, Lee SJ, Williams KM, Wong JY, De Vivo I & Savage SA (2015) Association between donor leukocyte telomere length and survival after unrelated allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for severe aplastic anemia. JAMA, 313, 594–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadalla SM, Wang T, Dagnall C, Haagenson M, Spellman SR, Hicks B, Jones K, Katki HA, Lee SJ & Savage SA (2016a) Effect of Recipient Age and Stem Cell Source on the Association between Donor Telomere Length and Survival after Allogeneic Unrelated Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation for Severe Aplastic Anemia. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation, 22, 2276–2282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadalla SM, Khincha PP, Katki HA, Giri N, Wong JY, Spellman S, Yanovski JA, Han JC, De Vivo I, Alter BP & Savage SA (2016b) The limitations of qPCR telomere length measurement in diagnosing dyskeratosis congenita. Mol Genet Genomic Med, 4, 475–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peffault de Latour R, Calado RT, Busson M, Abrams J, Adoui N, Robin M, Larghero J, Dhedin N, Xhaard A, Clave E, Charron D, Toubert A, Loiseau P, Socie G & Young NS (2012) Age-adjusted recipient pretransplantation telomere length and treatment-related mortality after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood, 120, 3353–3359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage S & Dufour C (2017) Classical inherited bone marrow failure syndromes with high risk for myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myelogenous leukemia. Seminars in Hematology, 54, 105–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheinberg P, Cooper JN, Sloand EM, Wu CO, Calado RT & Young NS (2010) Association of telomere length of peripheral blood leukocytes with hematopoietic relapse, malignant transformation, and survival in severe aplastic anemia. JAMA, 304, 1358–1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vulliamy TJ, Walne A, Baskaradas A, Mason PJ, Marrone A & Dokal I (2005) Mutations in the reverse transcriptase component of telomerase (TERT) in patients with bone marrow failure. Blood Cells Mol.Dis, 34, 257–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Wang T, Dagnall C, Haagenson M, Spellman SR, Hicks B, Jones K, Lee SJ, Savage SA & Gadalla SM (2017) Relative Telomere Length before Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation and Outcome after Unrelated Donor Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation for Acute Leukemia. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation, 23, 1054–1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Savage SA, Alsaggaf R, Aubert G, Dagnall CL, Spellman SR, Lee SJ, Hicks B, Jones K, Katki HA & Gadalla SM (2018) Telomere Length Calibration from qPCR Measurement: Limitations of Current Method. Cells, 7, 183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xhaard A, Cunha R, Busson M, Robin M, Dhedin N, Coman T, Cabannes-Hamy A, Sicre de Fontbrune F, Michonneau D, Socie G, Calado RT & Peffault de Latour R (2017) Clinical profile, biological markers, and comorbidity index as predictors of transplant-related mortality after allo-HSCT. Blood Adv, 1, 1409–1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi H, Baerlocher GM, Lansdorp PM, Chanock SJ, Nunez O, Sloand E & Young NS (2003) Mutations of the human telomerase RNA gene (TERC) in aplastic anemia and myelodysplastic syndrome. Blood, 102, 916–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi H, Calado RT, Ly H, Kajigaya S, Baerlocher GM, Chanock SJ, Lansdorp PM & Young NS (2005) Mutations in TERT, the gene for telomerase reverse transcriptase, in aplastic anemia. N.Engl.J.Med, 352, 1413–1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young NS (2013) Current concepts in the pathophysiology and treatment of aplastic anemia. Hematology: The Education Program of the American Society of Hematology, 2013, 76–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.