Abstract

Objective:

To examine development of bipolar spectrum disorders (BPSD) and other disorders in prospectively followed children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Method:

In the Longitudinal Assessment of Manic Symptoms (LAMS) study, 531 of 685 children age 6–12 (most selected for scores>12 on General Behavior Inventory 10-item Mania scale) had ADHD, 112 with BPSD, 419 without. With annual assessments for 8 years, retention averaged 6.2 years. Chi square analyses compared rate of new BPSD and other comorbidity between those with vs. without baseline ADHD, and between retained vs. resolved ADHD diagnosis. Cox regression tested factors influencing speed of BPSD onset.

Results:

Of 419 with baseline ADHD but not BPSD, 52 (12.4%) developed BPSD, compared to 16 of 110 (14.5%) without either baseline diagnosis. Those who developed BPSD had more non-mood comorbidity over the follow-up than those who did not develop BPSD (p=.0001). Of 170 who still had ADHD at eight-year follow-up (and not baseline BPSD), 26 (15.3%) had developed BPSD, compared to 16 of 186 (8.6%) who had ADHD without BPSD at baseline but lost the ADHD diagnosis (X2=3.82, p=.051). There was no statistical difference in whether ADHD persisted or not across new BPSD subtypes (X2=1.62, p=.446). Of those who developed BPSD, speed of onset was not significantly related to baseline ADHD (p=.566), baseline anxiety (p=.121), baseline depressiion (p=.185), baseline disruptive behavior disorder (p=.184), age (B=−.11 p=.092), maternal mania (p=.389), or paternal mania (B=.73, p=.056). Those who started with both diagnoses had more severe symptoms/impairment than those with later-developed BPSD and reported having ADHD first.

Conclusion:

In a cohort selected for symptoms of mania at age 6–12, baseline ADHD was not a significant prospective risk factor for developing BPSD. However, persistence of ADHD may marginally mediate risk of BPSD, and early comorbidity of both diagnoses increases severity/impairment.

Introduction

An important clinical issue is the rate at which children diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) develop bipolar disorder. A related issue is the rate of new comorbidities that develop over time. In this article, the term “conversion to bipolar’ refers to development of bipolar disorder whether or not the diagnosis of ADHD continues. Expanding our understanding of the role of ADHD in the development of other childhood disorders may help to elucidate underlying biological or environmental mechanisms that contribute to the accumulation of diagnoses over time, and could inform targeted interventions to prevent such a progression.

Currently, data regarding the relation between ADHD and bipolar disorder are inconsistent in methodology and outcomes. The Harvard group has reported a high rate of bipolar conversion (by disregarding the requirement for episodes); in a sample of youth with ADHD, 11% met their modified bipolar disorder criteria at baseline, 21% met these criteria 4 years later (Biederman et al., 1996). Similarly, the St. Louis group found a high rate of conversion to bipolar disorder by tracking manic symptoms without requiring that symptoms occur episodically (Tillman & Geller, 2006). On the other hand, when episodes are required for a bipolar diagnosis, cross-sectional studies report co-occurrence of the two disorders only at the rate expected by chance in the clinical population studied (Hazell, Carr, Lewin, Sly, 2003; Bagwell, Molina, Kashdan, Pelham, Hoza, 2006). In the LAMS clinical sample of 707 children, 538 had ADHD, 162 had bipolar spectrum disorders (BPSD), 117 had both, and 124 had neither, about the amount of overlap expected by chance (Arnold et al., 2011). Further, no family history overlap was found; each disorder “bred true” (Arnold et al., 2012).

The Multimodal Treatment Study of children with ADHD (the MTA) found 2.4% of combined-type ADHD had mania or hypomania as determined by the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children and licensed-clinician interview (4.3% depression) at baseline; 8 years later 1.8% had developed mania, hypomania, or psychosis and 5.8% had developed depression (Arnold et al., 2012; Molina et al., 2009). In other studies, ADHD has been associated with earlier bipolar disorder onset (Henin et al., 2007; Masi et al., 2006), However, other factors may better explain the association (e.g., overall burden of familial psychopathology; Birmaher et al., 2009, 2010). Thus, it is not clear whether children with ADHD are more likely to develop bipolar disorder than their peers.

A related consideration is whether those with both ADHD and BPSD develop their manic/hypomanic symptoms younger/earlier than those with only BPSD, which would support the hypothesis that those with both disorders have a different, “eary onset” type of BPSD. In this regard Arnold et al (2011) reported no difference in the age of onset of mood symptoms in those with BPSD versus those with BPSD + ADHD.

The Longitudinal Assessment of Manic Symptoms (LAMS) sample presents an opportunity to clarify these issues prospectively. Participants were recruited specifically to track development of bipolar spectrum disorders (BPSD: bipolar I [BPI] or II [BPII], cyclothymic disorder [CYC], or bipolar disorder not otherwise specified [BP-NOS]) in a child mental health population, with symptoms of mania as the main inclusion criterion. At baseline, 61% had ADHD alone, 7% BPSD alone, 16% both, and 17% neither (total=101% due to rounding). This sample has been followed-up every six months for eight years, with ongoing analyses.

We tested these hypotheses:

Over an 8-year period, children starting with ADHD without BPSD will develop BPSD at a higher rate than those starting with neither disorder;

Those who convert to BPSD will accumulate more comorbid disorders (not counting mood disorders) than those who don’t convert;

Those who continue to have diagnosable ADHD at the 96-month follow-up will have a higher rate of BPSD than those who no longer meet criteria for ADHD;

After adjusting for age, those who started with both diagnoses will have more severe symptoms and impairment than those who newly developed BPSD; and

As an exploratory analysis, cumulative rates of newly diagnosed ADHD by the 96-month follow-up in children who started with BPSD but not ADHD will be determined using DSM-5 criteria.

Method

Participants

Written informed consent from the parents/guardians and assent from the child participants used forms and procedures approved by the local university Institutional Review Boards. Participants aged 6–12 were recruited from nine child outpatient mental health clinics associated with Case Western Reserve University, University of Pittsburgh, Ohio State University, and University of Cincinnati. Parents/guardians completed the Parent General Behavior Inventory – 10 Item Mania Scale (PGBI-10M) (Youngstrom et al., 2008, 2018) to screen for symptoms of mania (SM). The PGBI-10M scores 10 hypomanic, manic, and biphasic symptoms 0–3 for a total score 0 to 30. All children whose parent/guardian rated them 12 or more (SM+) were invited, along with some demographically matched children with scores 11 or lower (SM-). Details are described separately (Horwitz et al., 2010).

Procedure

Diagnosis was by the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Episode with additional items from the Washington University St. Louis Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders (K-SADS-PL-W) (Kaufman et al., 1997; Geller, Williams, Warner, Zimmerman 1998; Geller et al, 2001). A diagnosis of BPSD required episodes; symptoms that occurred only during episodes did not count for ADHD and chronic ADHD symptoms did not count for BPSD. This is in contrast to other studies that have not required episodes, which may result in “double counting” symptoms toward multiple diagnoses, artificially inflating the rate of comorbidity. This can be particularly problematic when considering BPSD and ADHD diagnoses as many symptoms (e.g., impulsivity, distractibility, hyperactivity) are common to both.

The LAMS study used the same criteria for bipolar disorder not otherwise specified (BP NOS) as the Course and Outcome of Bipolar Youth (COBY) study (Axelson, 2006; Birmaher, 2006): (a) elated mood plus at least two other symptoms of mania (grandiosity, decreased need for sleep, pressured speech, racing thoughts, increased goal-directed activity), or irritable mood plus at least three other symptoms of mania; (b) change in the participant’s level of functioning (increase or decrease); (c) symptoms present for a total of at least four hours within 24 hours on at least 4 days. Bipolar I, II, and cyclothymic disorder were diagnosed according to DSM-IV criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2001).

A licensed child psychiatrist or psychologist reviewed and confirmed all diagnoses. Inter-rater reliability was achieved on video-taped administrations of the K-SADS-PL-W (kappa=0.82, 0.93 on BPSD). For onset age of BPSD symptoms, the earliest of BPSD diagnosis, any episodic manic symptoms, or any depressive symptoms was used.

At the beginning of the interview, interviewers gathered a developmental history to see whether there was a history of mood episodes versus a more chronic history of problems or both; e.g., interviewers asked whether “difficulty concentrating,” was chronic or only sometimes (more episodic). If mood episodes emerged, the interviewer would ask if the poor concentration occurred or intensified only in the mood episode. Symptoms occurring only episodically, in the company of other mood symptoms, were scored in the mood module (mania or depression). Symptoms that clearly extended beyond a mood episode were coded in other disorders. Symptoms that pre-dated a mood episode but clearly worsened during the episode could be counted for both diagnoses (Youngstrom, Birmaher, & Findling, 2008).

Other measures.

Global functioning was measured by the Children’s Global Assessment Scale (C-GAS; Shaffer, 1983). Impairment was assessed by the Child and Adolescent Symptom Inventory-4-Parent Version (CAASI-4R), rated on a 0–3 scale (Gadow & Sprafkin, 1994). Caregivers rated child symptoms across five domains (inattentive, hyperactive, conduct, mania, depression. Mania in biological parents was assessed using The Family History Screen (Weissman et al., 2000; Milne et al., 2006). A positive parental history of mania resulted from parents endorsing yes for “extreme elated mood” plus three supporting symptoms (more talkative, inflated self-esteem, decreased need for sleep, racing thoughts, more distractible than usual, more restless, and excessive involvement in pleasurable activities) or yes for extreme irritable mood with four supporting symptoms. In cases with missing data, if enough symptoms were known to meet the criteria above, the parent was scored positively. If the parent could not meet criteria even if missing symptoms were available (e.g., if neither extreme elated mood nor extreme irritable mood was endorsed), the parent was scored negatively.

Statistical analysis

Chi square analyses were used to test hypotheses comparing development of diagnoses (i.e., dichotomous outcomes). Cox regression was used to evaluate factors that influence how quickly youth met criteria for a BPSD, including baseline ADHD diagnosis, anxiety disorder diagnosis, depression diagnosis, family history of bipolar disorder, and medication at baseline (stimulant, antipsychotic, antidepressant).

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to evaluate differences in symptom severity across groups (i.e, continuous outcomes).

For all analyses except whether youth with a baseline diagnosis of BPSD were more likely to develop ADHD and whether those with both disorders were worse at FU, those with BPSD at baseline were excluded from analyses.

Results

The baseline LAMS sample included 707 youth; 22 were excluded from follow-up (neurodevelopmental disorders and/or IQ<70, n=16; miscellaneous reasons such as becoming a ward of the state or moving out of state, n=6). Among the remaining 685, the average follow-up was 6.2 years (SD=3.2). At baseline, the average age was 8.9 (1.9); 67% were male; 72% were white; 4.5% were Hispanic. Demographic and clinical characteristics are described in Table 1 for those still available at follow-up.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of those available at follow-up

| Baseline ADHD, Baseline BPSD A |

Baseline ADHD Follow-Up BPSD B |

Baseline BPSD No Baseline ADHD C |

Baseline ADHD No BPSD at any point D |

No Baseline ADHD, No Baseline BPSD E |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 112 | 52 | 44 | 367 | |

| % | |||||

| Female | 41%D | 35% | 48%D | 23%A,C | 49%D |

| White | 79% | 69% | 82% | 67% | 76% |

| Hispanic | 5% | 10% | 5% | 4% | 3% |

| BP I | 43% | 0% | 48% | 0% | 0% |

| BP II | 0% | 0% | 7% | 0% | 0% |

| Cyclothymic disorder | 8% | 0% | 5% | 0% | 0% |

| BP NOS | 49% | 0% | 41% | 0% | 0% |

| Comorbid anxiety | 47%B | 69%A,D,E | 57% | 42%B | 45%B |

| Comorbid DBD | 64%C,E | 79%C,D,E | 27%A,B,D | 60%B,C | 46%A,B |

| Paternal mania | 13% | 12% | 18%D,E | 7%C | 4%C |

| Maternal mania | 21%D,E | 12% | 25%D,E | 9%A,C | 10%A,C |

| Antidepressant | 13% | 13% | 23% | 10% | 13% |

| Stimulant | 46%C,E | 50%C,E | 9%A,B,D | 47%C,E | 9%A,B,D |

| Mood stabilizer | 17%D,E | 8% | 16%D | 3%A,C | 5%A |

| Mean (SD) | |||||

| Age at Baseline | 9.04(2.0)C | 8.38(1.9)C | 10.00(2.1)A,B,D | 8.77(1.9)C | 9.01(1.8)C |

| Average number of medications | 1.52(1.2)D,E | 1.42(1.2)D,E | 1.23(1.3)E | .95(.9)A,B,E | .6(1.0)A,B,C,D |

| C-GAS | 50.08(9.1) | 52.71(9.6) | 54.77(9.1) | 55.81(9.6) | 57.86(11.5)A,B |

different from baseline ADHD + baseline BPSD, p<.05

different from baseline ADHD + follow-up BPSD, p<.05

different from baseline BPSD + no ADHD, p<.05

different from baseline ADHD + no BPSD, p<.05

different from no baseline ADHD + no baseline BPSD, p<.05

ADHD = attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; BPSD =bipolar spectrum disorder; BP NOS = bipolar disorder not otherwise specified; DBD = disruptive behavior disorder (oppostional-defiant and conduct); C-GAS = Child Global Assessment Scale

Of the 685, 68 did not continue beyond baseline. Of these 68, 42 had ADHD, 5 had BPSD, and 10 had both ADHD and BPSD. Study drop-outs, compared to study persisters, were less likely to have a comorbid disruptive behavior disorder (DBD) at baseline (X2=5.93, p=.015). Another 188 were lost to follow-up by the 96-month assessment, however, their intermediate data are included in analyses.

At baseline, 78% (n=531) of the sample met criteria for ADHD; a minority (23%, n=156) met criteria for BPSD (69 BPI, 3 BPII, 11 CYC, 73 BP-NOS). Of these, 112 had both ADHD and BPSD at baseline (16% of the total sample; 21% of youth with ADHD, 72% of youth with BPSD: 48 BPI, 10 CYC, 56 BP-NOS). Of the 156 youth who had BPSD at baseline, 44 (28%) did not have ADHD; 88 (56% of all with BPSD, 79% of those with both disorders) reported experiencing clinically significant symptoms of ADHD before they had clinically significant symptoms of BPSD; 13 (8% of all with BPSD, 12% of those with both disorders) experienced symptoms of BPSD first; 10 (6% of all with BPSD, 9% of those with both disorders) reported their ADHD and mood symptoms started at the same time; and 1 (1%) had missing information. While the overall proportion of youth in each BPSD subtype category with ADHD at baseline did not differ significantly (X2=7.58, p=.056), 82% of those with CYC and none with BPII had ADHD (68% with BPI and 62% with BP-NOS had ADHD).

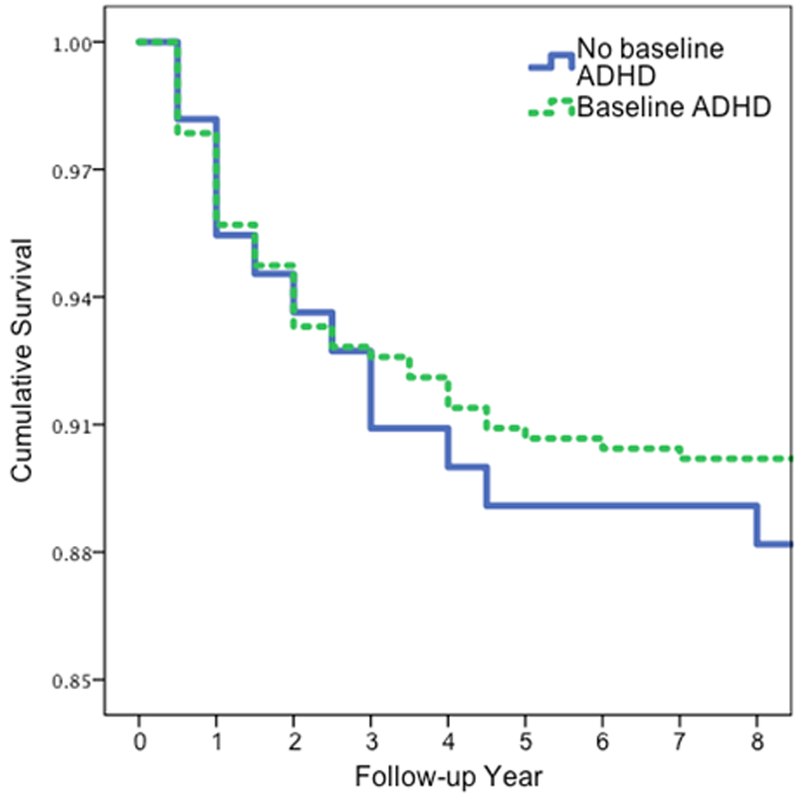

In prospective analyses (Fig. 1), baseline ADHD was not associated with new onset of BPSD, X2=0.05, p=.827. Additionally, ADHD subtype was not significantly associated with differences in BPSD outcome (X2=5.51, p=.138); 10% of youth with combined type, 6% with inattentive type, 18% with hyperactive type, and 11% with ADHD NOS developed BPSD. Medication class (antidepressant, mood stabilizer, or stimulant) at baseline was not related to risk for BPSD over follow-up, regardless of whether there was a baseline diagnosis of ADHD. Of those with baseline ADHD but not BPSD, 12.4% (52/419) developed BPSD (19 BPI, 2 BPII, 31 BP-NOS), compared to 14.5% of those without baseline ADHD (16/110; 6 BPI, 3 BPII, 7 BP-NOS). The difference in the subtype of BPSD cases that emerged over follow-up based on their ADHD status at baseline was not statistically significant (X2=4.25, p=.119). Of 170 who still had ADHD at eight-year follow-up (and not baseline BPSD), 26 (15.3%) had developed BPSD, compared to 16 of 186 (8.6%) who had ADHD and not BPSD at baseline but lost the ADHD diagnosis; this was a trend (X2=3.82, p=.051).

Figure 1.

Time to bipolar spectrum disorder diagnosis in those with (n=52 of 419) and without ADHD (n=16 of 110) at baseline (of those who did not have BPSD at baseline). ADHD =attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Difference not significant.

Cox regression analyses indicated that baseline ADHD diagnosis was not significantly related to speed of BPSD conversion (B=−.16, p=.566).

Table 1 shows demographic and clinical characteristics for five groups: baseline BPSD+ADHD, baseline ADHD with follow-up BPSD, baseline BPSD without ADHD, baseline ADHD without BPSD at any time, and neither BPSD nor ADHD at baseline. Those with ADHD at baseline who developed a BPSD were more likely to have anxiety other than post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) at some point during the 8 years of follow-up than those who did not develop BPSD (69% vs. 43%: X2=16.17, p=.003). They were also more likely to have DBD (79% versus 60%, X2=34.99, p<.0005). On the other hand, youth with ADHD who developed a BPSD were nominally less likely than youth with ADHD who did not develop BPSD to have PTSD, OCD, eating disorder, or substance use disorder at some point over the follow-up (60% versus 66%, X2=.51, p=.472).

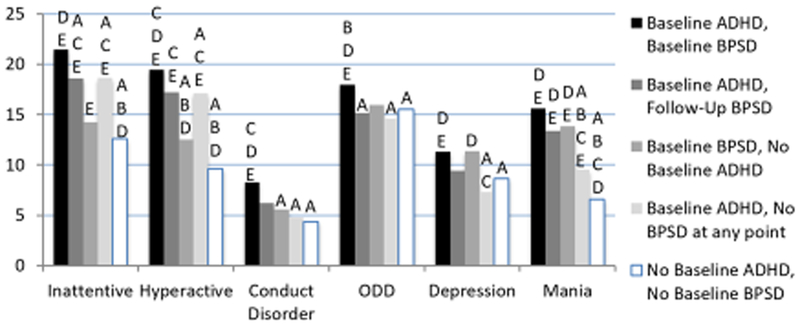

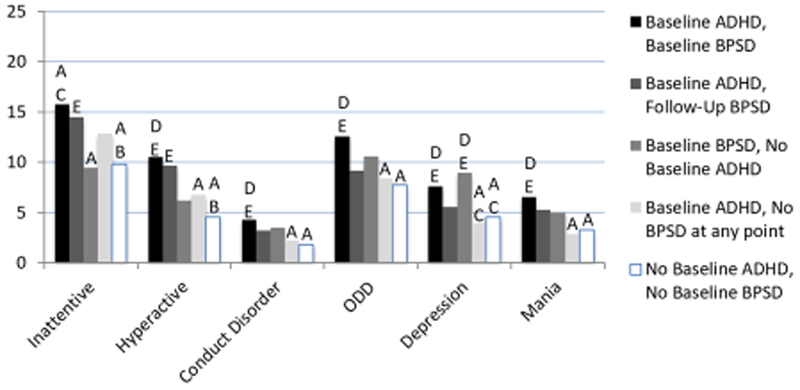

We compared dimensional scores on the CAASI-4R (Inattentive, Hyperactive, Conduct Disorder [CD], Mania, Depression) for five groups of youth (scores for youth under 12 and youth 12-and-older were computed separately to account for developmental differences): those who met criteria for both ADHD and BPSD at baseline; those with ADHD who later developed BPSD; those with ADHD but no BPSD throughout the study; those with BPSD at baseline but no ADHD throughout the study, and those with neither BPSD or ADHD at baseline (see Figures 2 and 3). With the exception of depressive symptoms, the ADHD+BPSD baseline group was the most symptomatic (the BPSD alone group was equally depressed) at both baseline and 96-month follow-up (this pattern also held across the other time points; results available upon request). Interestingly, all four groups became less symptomatic over time, with lower scores at the 96-month follow-up than at baseline, when treatment was starting. Relatedly, the ADHD+BPSD group had the lowest baseline C-GAS scores (F=10.62, p<.0001), but were not different from the other BPSD groups at 96-month follow-up (ADHD alone was significantly higher; F=4.46, p=.002).

Figure 2. Baseline Child and Adolescent Symptom Inventory scores across groups.

A different from baseline ADHD + baseline BPSD, p<.05

B different from baseline ADHD + follow-up BPSD, p<.05

C different from baseline BPSD + no ADHD, p<.05

D different from baseline ADHD + no BPSD, p<.05

E different from no baseline ADHD + no baseline BPSD, p<.05

Figure 3. Eight-year follow-up Child and Adolescent Symptom Inventory scores across groups.

A different from baseline ADHD + baseline BPSD, p<.05

B different from baseline ADHD + follow-up BPSD, p<.05

C different from baseline BPSD + no ADHD, p<.05

D different from baseline ADHD + no BPSD, p<.05

E different from no baseline ADHD + no baseline BPSD, p<.05

Exploratory analyses

Baseline ADHD was not significantly associated with increased risk for depression over follow-up, X2=2.44, p=.118. Of those with baseline ADHD, 14% developed a depressive disorder (MDD or dysthymic disorder, n=76) compared to 18% of those without ADHD at baseline (n=30).

Youth with baseline BPSD (excluding those with ADHD at baseline) were not more likely to develop ADHD over follow-up (21%, n=9, versus 32%, n=35, of those without BPSD; X2=1.99, p=.158).

Discussion

These findings confirm previous reports suggesting independence of ADHD and BPSD (e.g., Arnold et al., 2011). The new data show that neither disorder predisposed development of the other. Thus hypothesis 1 is not upheld. Importantly, in this study episodes were required for a bipolar diagnosis; symptoms that occurred only during episodes were not counted toward ADHD, as instructed in DSM, ICD, and ISBD guidelines (Youngstrom, Birmaher, Findling, 2008). The rates of new BPSD diagnoses by 8-year follow-up were almost identical between those who had ADHD at baseline and those who did not. Further, baseline BPSD did not predispose youth to develop ADHD over time; only 21% of those with baseline BPSD compared to 32% of those without baseline BPSD developed ADHD by the 8year follow-up. (Although these rates are above general population rates, they are not unexpected in this clinical sample.) This is compatible with the lack of association between baseline ADHD and BPSD in the Cox regression (Axelson et al., 2015).

Our second hypothesis was upheld-- those with baseline ADHD who develop BPSD also accumulate more comorbid disorders (not counting mood disorders) than those who do not develop BPSD. Strikingly, rates were nearly double for converters (65% versus 35%, p=.0001). As expected, the main comorbidities were disruptive behavior disorders and anxiety.

There was only marginal support for our third hypothesis--that those who continue to have diagnosable ADHD at 8 years would have a higher rate of BPSD than those who lose the ADHD diagnosis (15.3%% versus 8.6%; p=0.051). This leaves that question ambiguous.

Our fourth hypothesis was strongly supported. Two diagnoses early on are worse than one. At both baseline and 96 months, those who started with both diagnoses had more severe symptoms and impairment than those with ADHD who newly developed BPSD.

The fact that 79% of those with both disorders at baseline experienced clinically significant symptoms of ADHD before significant symptoms of BPSD may seem to suggest that ADHD is associated with very early onset BPSD, but not with typical-onset BPSD. However, a baseline report on this sample (Arnold et al, 2011) found that those with both disorders and those with only BPSD did not have significantly different age of onset of mood symptoms. The retrospectively reported sequence of ADHD before BPSD appears to be an artifact of different developmental onset ages of two independent disorders.

This study had several limitations that must be considered in interpreting the findings. First, all participants were seeking treatment at baseline and most were selected for having symptoms of mania. This may limit the generalizability of the findings. However, it might be argued that any bias this introduces would tend to elevate the proportion converting to BPSD rather than keep it low. Second, many youth already had BPSD at baseline, so it was not possible to prospectively investigate the association between ADHD and BPSD in those individuals. Third, this study focused on the impact of baseline ADHD on development of BPSD and related questions. Many other important questions (e.g., what happens to those with major depression at baseline) remain to be answered.

In summary, these findings suggest that ADHD and BPSD are independently occurring diagnoses, compatible with previous reports. These results reinforce the importance of assessing symptom episodicity; earlier studies (e.g. Biederman et al., 1996; Tillman & Geller, 2006) that showed a strong association between ADHD and BPSD did not require episodicity, which may have resulted in symptoms being attributed to both disorders in contradiction of diagnostic guidelines from DSM and ICD. We did find a weak (almost significant) signal for persistent ADHD to be more associated with 8-year follow-up BPSD than remitting ADHD, reinforcing the importance of ongoing reevaluation of diagnoses when working longitudinally with youth. An important next step in this line of research would be to follow a younger cohort of youth, who have not yet developed BPSD, to further understand the pattern of diagnostic progression.

Key points.

In 6-to-12-year-old children selected for the presence of manic symptoms, having ADHD did not alter the likelihood of meeting threshold criteria for a bipolar diagnosis within the next eight years. However, persistence of ADHD symptoms was marginally (p=.051) associated with development of BPSD compared to those whose ADHD resolved.

Speed of BPSD onset was not related to baseline ADHD.

Those who developed BPSD had more non-mood comorbidity than those who did not develop BPSD.

Acknowledgements

L.E.A. has received research funding from Curemark, Forest, Lilly, Neuropharm, Novartis, Noven, Roche, Shire, Supernus, and YoungLiving (as well as NIH and Autism Speaks), has consulted with Gowlings, Neuropharm, Organon, Pfizer, Sigma Tau, Shire, Tris Pharma, and Waypoint. He has been on advisory boards for Arbor, Ironshore, Novartis, Noven, Otsuka, Pfizer, Roche, Seaside Therapeutics, Sigma Tau, Shire, and received travel support from Noven. R.L.F. receives or has received research support, acted as a consultant and/or served on a speaker’s bureau for Aevi, Akili, Alcobra, Allergan, Amerex, American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, American Psychiatric Press, Arbor, Bracket, Daiichi-Sankyo, Epharma Solutions, Forest, Genentech, Insys, Ironshore, KemPharm, Lundbeck, Merck, NIH, Neurim, Noven, Nuvelution, Otsuka, PCORI, Pfizer, Physicians Postgraduate Press, Roche, Sage, Shire, Sunovion, Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Syneurx, Teva, TouchPoint, Tris, and Validus. M.A.F. receives royalties from Guilford Press, American Psychiatric Press, Child & Family Psychological Services, and research funding from Janssen. E.A.Y. has received grant or research support from the National Institute of Mental Health, the American Psychological Association, and the Association for Psychological Science. He has served on the advisory board/DSMB for a National Institutes of Health-sponsored project. He has served as a consultant to Janssen and Joe Startup Technologies. He has served as a consulting editor of the Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology and on the editorial board of the Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. He has received honoraria from the Nebraska Psychological Association and the American Psychological Association. He has received royalties from the American Psychological Association and Guilford Press. He has held stock options / ownership in Joe Startup Technologies and Helping Give Away Psychological Science (501c3). A.V.M. has received research funding from the American Psychological Foundation. The remaining authors have declared that they have no competing or potential conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: See Acknowledgements for full disclosures.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2001). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th Text Revision ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold LE, Demeter C, Mount K, Frazier TW, Youngstrom EA, Fristad MA, Birmaher B, Findling RL, Horwitz SM, Kowatch R, & Axelson DA (2011). Pediatric bipolar spectrum disorder and ADHD: comparison and comorbidity in the LAMS clinical sample. Bipolar Disorders, 13, 509–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold LE, Mount K, Frazier TW, Demeter C, Youngstrom EA, Fristad MA, Birmaher B, Horwitz S, Findling RL, Kowatch R, & Axelson DA (2012). Pediatric bipolar disorder and ADHD: family history comparison in the LAMS clinical sample. Journal of Affective Disorders, 141(2–3), 382–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelson D, Birmaher B, Strober M, Gill MK, Valeri S, Chiappetta L, Ryan N, Leonard H, Hunt J, Iyengar S, Bridge J, & Keller M (2006). Phenomenology of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry 2006, 63(10), 1139–1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelson D, Goldstein B, Goldstein T, Monk K, Yu H, Hickey MB, Sakolsky D, Diler R, Hafeman D, Merranko J, Iyengar S, Brent D, Kupfer D, & Birmaher B (2015). Diagnostic Precursors to Bipolar Disorder in Offspring of Parents With Bipolar Disorder: A Longitudinal Study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 172(7), 638–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagwell C, Molina B, Kashdan T, Pelham W, & Hoza B (2006). Anxiety and mood disorders in adolescents with childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders ,14, 178–187. [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Faraone S, Mick E, Wozniak J, Chen L, Oulette C, Marrs A, Moore P, Garcia J, Mennin D, & Lelon E (1996). Attention-deficit and hyperactivity disorder and juvenile mania: an over-looked comorbidity? Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 35(8), 997–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Axelson D, Strober M, Gill MK, Valeri S, Chiappetta L, Ryan N, Leonard H, Hunt J, Iyengar S, & Keller M (2006). Clinical course of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63(2), 175–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Axelson D, Monk K, Kalas C, Goldstein B, Hickey MB, Obreja M, Ehmann M, Iyengar S, Shamseddeen W, Kupfer D, & Brent D (2009). Lifetime psychiatric disorders in school-aged offspring of parents with bipolar disorder: The pittsburgh bipolar offspring study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 66(3), 287–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Axelson D, Goldstein B, Monk K, Kalas C, Obreja M, Hickey MB, Iyengar S, Brent D, Shamseddeen W, Diler R, & Kupfer D (2010). Psychiatric Disorders in Preschool Offspring of Parents With Bipolar Disorder: The Pittsburgh Bipolar Offspring Study (BIOS). American Journal of Psychiatry, 167(3), 321–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadow KD, & Sprafkin J (1994). Child Symptom Inventories Manual. Stony Brook, NY: Checkmate Plus. [Google Scholar]

- Geller B, Warner K, Williams M, & Zimerman B (1998) Prepubertal and young adolescent bipolarity versus ADHD: Assessment and validity using the WASH-U-KSADS, CBCL and TRF. Journal of Affective Disorders, 51(2), 93–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller B, Zimerman B, Williams M, Bolhofner K, Craney JL, DelBello MP, & Soutullo C (2001). Reliability of the Wahsington University in St. Louis Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (WASH-U-KSADS) mania and rapid cycling sections. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(4), 450–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazell PL, Carr V, Lewin TJ, & Sly K (2003). Manic symptoms in young males with ADHD predict functioning but not diagnosis after 6 years. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 42(5), 552–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henin A, Biederman J, Mick E, Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Sachs GS, Wu Y, Yan L, Ogutha J, & Nierenberg AA (2007). Childhood antecedent disorders to bipolar disorder in adults: A controlled study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 99, 51–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz SM, Demeter CA, Pagano ME, Youngstrom EA, Fristad MA, Arnold LE, Birmaher B, Gill MK, Axelson D, Kowatch RA, Frazier TW, & Findling RL (2010). Longitudinal Assessment of Manic Symptoms (LAMS) Study: Background, design, and initial screening results. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 71(11), 1511–1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, Williamson D, & Ryan N (1997). Schedule of Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): Initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(7), 980–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masi G, Perugi G, Toni C, Millepiedi S, Mucci M, Bertini N, & Pfanner C (2006). Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder – bipolar comorbidity in children and adolescents. Bipolar Disorders, 8(4), 373–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milne BJ, Caspi A, Harrington H, Poulton R, Rutter M, & Moffitt TE (2009). Predictive value of family history on severity of illness. Archives of General Psychiatry, 66(7), 738–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina BS, Hinshaw SP, Swanson JM, Arnold LE, Vitiello B, Jensen PS, Epstein JN, Hoza B, Hechtman L, Abikoff HB, Elliott GR, Greenhill LL, Newcorn JH, Wells KC, Wigal T, Gibbons RD, Hur K, Houck PR, & MTA Cooperative Group. (2009). The MTA at 8 years: Prospective follow-up of children treated for combined-type ADHD in a multisite study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 48(5), 484–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Gould MS, Brasic J, Ambrosini P, Fisher P, Bird H, & Aluwahlia S (1983). A Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS). Archives of General Psychiatry, 40(11), 1228–1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tillman R, & Geller B (2006). Controlled study of switching from attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder to a prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar I disorder phenotype during 6-year prospective follow-up: Rate, risk, and predictors. Development and Psychopathology, 18(4), 1037–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Wickramaratne P, Adams P, Wolk S, Verdeli H, & Olfson M (2000). Brief screening for family psychiatric history: The family history screen. Archives of General Psychiatry, 57(7), 675–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youngstrom EA, Meyers O, Demeter C, Youngstrom J, Morello L, Piiparinen R, Feeny N, Calabrese JR, & Findling RL (2005). Comparing diagnostic checklists for pediatric bipolar disorder in academic and community mental health settings. Bipolar Disorders, 7(6), 507–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youngstrom EA, Frazier TW, Demeter C, Calabrese JR, & Findling RL (2008). Developing a 10-item Mania Scale from the Parent General Behavior Inventory for Children and Adolescents. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 69(5), 831–839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youngstrom EA, Birmaher B, & Findling RL (2008). Pediatric bipolar disorder: Validity, phenomenology, and recommendations for diagnosis. Bipolar Disorders, 10, 194–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youngstrom E, Van Meter A, Frazier TW, Youngstrom JK, & Findling RL (2018). Developing and Validating Short Forms of the Parent General Behavior Inventory Mania and Depression Scales for Rating Youth Mood Symptoms AU - Youngstrom, Eric A. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 1–16. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2018.1491006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]