Abstract

Continuous Chirality Measure (CCM) is a computational metric by which to quantify the chirality of a compound. In enantioselective catalysis, prior work has postulated that CCM is correlated to selectivity and can be used to understand which structural features dictate catalyst efficacy. Herein, the investigation of CCM as a metric capable of guiding catalyst optimization is explored. Conformer-dependent CCM is also explored. Finally, CCM is used with Sterimol parameters to significantly improve the performance of Random Forest models.

Keywords: Continuous chirality measure, Machine learning, Multivariate analysis

1. Introduction

The development of synthetic methods for the production of enantiomerically enriched compounds from achiral starting materials is of paramount importance in organic chemistry. Accordingly, the field of enantioselective catalysts, wherein substoichiometric quantities of a chiral catalyst can be used to generate enantiomerically enriched compounds, has risen to the forefront of research in the development of new synthetic reactions. Despite this rise in prominence, the general strategy for the development of chiral catalysts has incorporated relatively little innovation compared to the rest of the field. Catalyst design remains primarily reliant on chemical intuition, wherein practitioners qualitatively identify relationships between catalyst structure and selectivity. Whereas the intuition of a skilled experimentalist is still valued, even the most experienced veteran is incapable of analyzing vast quantities of data and identifying the multidimensional relationships pertaining to catalyst efficacy. To address these inherent limitations, synthetic chemists have embraced the use of computational tools for catalyst design, as reflected in the numerous reviews in the area [1–12]. Of these, chemoinformatics provides an attractive approach to catalyst development for several reasons: (1) no mechanistic information is needed, (2) catalyst structures can be characterized by 3D-descriptors (numerical representations of molecular properties derived from the 3-D structure of the molecule) which quantify the steric and electronic properties of thousands of candidate molecules, and (3) the suitability of a catalyst candidate can be quantified by comparing its properties to a computationally derived model on the basis of experimental data [13–15].

A major challenge in the field of chemoinformatics applied to enantioselective catalysis is the identification of numerical properties that adequately represent the aspects of chemical systems responsible for enantioinduction, The first example of 3D-QSAR applied to asymmetric catalysis was published by Norrby and coworkers, wherein structural features of palladium catalysts were used as descriptors in predicting isomeric ratios allylic substitution reactions [16], Gasteiger and coworkers later introduced conformer independent and conformer dependent chirality codes to describe molecular chirality in the form of a radial distribution function [17,18], The Kozlowski and Lipkowitz laboratories first applied Molecular Interaction Field (MIF)-based approaches toward solving problems in asymmetric catalysis [19,20], Similarly, other laboratories have used related approaches to assist understanding and designing enantioselective catalysts [21–42], For example, Sigman and coworkers have pioneered the use of physical parameters in multivariate regression analysis to identify selective catalysts and garner mechanistic insight into enantioselective reactions [43–45], Though not exhaustive, the studies mentioned (and references cited therein) represent the state-of-the-art approaches for the “mathematization of chemistry”, as defined by Ugi to represent processes wherein molecules are represented numerically, which is necessary to enable computer-guided solutions [46].

A particularly intriguing method to represent the chirality of molecules is the Continuous Chirality Measure (CCM). Continuous Chirality Measure was first described by Avnir and coworkers as an extension of Continuous Symmetry Measure (CSM) [47–50]. The crux of this concept is that rather than considering chirality as binary property of a molecule (i.e. either present or not present), the “degree of chirality” is a quantifiable property of a chiral molecule. Lipkowitz eloquently describes this concept using substituted 2,2’-biphenyls (e.g. BINOL) as an example [51]. When the biphenyl is perfectly planar (dihedral angle of 0° between the two aromatic rings), the molecule is achiral. If this dihedral angle is increased an infinitesimally small amount away from 0°, the molecule becomes chiral. Intuitively, as the dihedral angle is increased further away from 0°, the molecule becomes “more chiral”; thus, we would expect this molecule to exhibit improved performance in enantiodifferentiation tasks than “less chiral” molecules. It follows naturally that CCM has potential to be a useful descriptor in chemoinformatics applied to asymmetric catalysis.

Avnir constructed a mathematical formula capable of calculating this degree of chirality, derived from CSM (eq. (1)) as:

| (1) |

wherein G is a given symmetry group, Pi is the original set of points, is the corresponding set of points in the nearest G-symmetric configuration, and n is the total number of configuration points. Interpretation of this equation is best described by the original authors [50]: “The meaning of eq. (1) is the following: find a set of points which possess the desired symmetry (G symmetry), such that the total (normalized) distance from the original shape Pi is minimal.” Because chirality is the absence of improper symmetry elements, searching over all achiral symmetry groups will give a minimal distance to achirality. Thus, molecules with a greater minimal distance to achirality (larger values of S′) are more chiral.

Lipkowitz and coworkers were the first to explore the relationship between CCM and enantioselectivty [51]. Under the premise that the chirality content of a molecule should correlate with enantioselectivity in catalytic, enantioselective reactions, the Diels-Alder cycloaddition catalyzed by chiral 1,1′-biaryl-2,2′-diolligated Lewis acids was investigated, and a nonlinear correlation between CCM and enantioselectivity was identified. From this analysis, a maximum CCM value is found, indicating that not all atoms in a molecule contributing to overall chirality also contribute to enantiodifferentiation. The subunit of the molecule with CCM values that best correlate with enantioselectivity is termed a chiraphore, which is the subunit of a molecule responsible for its stereodifferentiating ability. A similar protocol was employed by Lipkowitz, Schefzick, and Avnir in which CCM was employed to identify the structural features of bisoxazoline ligands responsible for stereoinduction in an enantioselective Diels-Alder reaction [52,53]. This method was also employed in an analysis of the Katsuki-Jacobsen epoxidation reaction, identifying structural distortions related to chirality content [54]. Bellarosa and Zerbetto introduced a modification to the CCM method termed electronic chirality measures (ECM), wherein the chirality is measured from the electronic wave function [55]. The ECM demonstrated stronger correlation with enantioselectivity than the analogous CCM values in enantioselective aminohydroxylation reactions. Finally, continuous chirality measures have also been used to analyze stereodifferentiation at critical points along the reaction coordinate of a ruthenium-catalyzed, enantioselective, transfer hydrogenation reaction [56].

In each of these examples, CCM has been used as a single parameter used to represent catalyst efficacy. However, most publications: (1) assume that CCM and enantioselectivity correlate linearly across the entirety of the CCM coordinate, an assumption disproven in the seminal publication of the application of CCM to enantioselective catalysis, and (2) do not offer experimental validation for the hypotheses extracted from CCM analysis. Further, it is surprising that CCM and ECM have not been used in multivariate analyses given their perceived success in univariate analysis. Interestingly, calculation of CCM is accessible to the broader community and requires no computing expertise to calculate, thanks to a website created by Avnir et al. for calculating CCM [57].

Thus, we set out to experimentally validate if CCM could be used as a single parameter descriptor to facilitate catalyst optimization and to investigate whether CCM-derived descriptors can be used in machine learning procedures to enable predictive modeling. Further, we have investigated the influence of molecular conformation on CCM values and have developed conformation-dependent CCM values. To evaluate these parameters, our previously published dataset employing chiral, BINOL-derived phosphoric acids in the enantioselective formation of chiral N,S-acetals, a reaction developed by Antilla et al. [58], was used to identify correlations and construct machine learning models (Scheme 1) [32]. This dataset has a total of 43 different catalysts, each of which was evaluated in different reactions with 25 unique substrate combinations. The 25 substrate combinations are derived from every pairwise combination of imine electrophile and thiol nucleophile depicted in Scheme 1. Thus, by using substrate descriptors, each catalyst provides 25 data points, for a total of 1075 reaction data points.

Scheme 1.

2. Calculating CCM

As previously stated, a valuable feature of CCM is that it can be readily calculated at no cost by using the website created by Avnir et al. [57] In the work below, many permutations of CCM were calculated including: (1) CCM of the lowest energy conformer of a given catalyst structure (CCM_LE), (2) CCM of the nearly C2-symmetric catalyst structure, where C2 symmetry is only broken by the presence of the acidic hydrogen atom (CCM_ C2–H), (3) CCM of the anion of the catalysts, in which the acidic hydrogen atom is removed so the structure is truly C2 symmetric (CCM_ C2-A), (4) CCM of the perceived chiraphore of the C2 symmetric structure, including only the oxygens attached to the phosphorus atom, the 2, 2′, 3, and 3′ carbon atoms, and the substituents at the 3,3′ positions (CCM_Chiraphore), and (5) an average CCM value, in which a conformer distribution for all catalysts were generated and minimized. The CCM value for each conformer is calculated, and the average CCM (CCM_A) and standard deviation (CCM_SD) are then used as parameters. Finally, (6) a Boltzmann averaged CCM (CCM_BA) value for the conformer library and weighted standard deviation (CCM_BSD) were also used to represent the relative populations of the conformers. In the calculation of the conformer dependent descriptors, it is worth noting that manually calculated CCM for all structures can be time intensive. For high-throughput analysis, alternatives are available through several GitHub repositories [59].

Conformer distribution calculations were carried out using Macromodel [60]. The calculations were done with the OPLS3 force field with no solvent. The maximum number of iterations was set to 2500 and the convergence threshold to 0.05 (wherein the calculation converges on the gradient). The search method employed was mixed torsional/low-mode sampling with maximum number of steps set to 1000,100 steps per rotatable bond specified, with an energy cutoff set to 7 kcal/mol. Redundant conformers were identified using a maximum atom deviation cutoff of 0.5 Å (RMSD of respective atomic coordinates). All other options were left as defaults. The geometry of each conformer was then optimized using semi-empirical (PM6) methods with Gaussian software [61]. Free energies for each conformer were calculated at the M06–2X level of theory with the 6–311G** basis set (full computational details are available in the Supporting Information).

Machine learning models were constructed with Python2 scripts using SciKitLearn [62]. In each case, 1000 data points were used in model generation and validation. The data was divided into two sets: (1) a subset of 300 reactions from the total 1000 member set for model development and (2) an external set of 700 reactions used for model validation. The original 300 reactions were split into five [63]-member sets for cross validation, and the internally validated model was then used to predict the remaining 700 reactions that were not used in model development. This process was repeated 10 times, wherein the partitioning of training and test sets was done randomly using a Python random number generator. The appropriate control experiment in which random features were used instead of chemically meaningful descriptors is provided in the Supporting Information.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. CCM in univariate analysis

Initial attempts to evaluate the use of CCM as the sole parameter to guide catalyst optimization were undertaken by first calculating the CCM for [46] different catalysts and plotting the experimentally observed enantioselectivities for the reaction in Scheme 2 using all 43 catalysts vs. CCM to identify any correlation. The experimental enantioselectivity data is given in Scheme 2. The CCM values of catalysts were calculated using [1]: CCM_LE, (2) CCM_ C2–H, (3) CCM_ C2-A, and (4) CCM_Chiraphore. A summary of results is presented in Fig. 1.

Scheme 2.

Fig. 1.

Plots of free energy differential (∆∆G‡ for e.r.) plotted against the CCM calculated four different ways.

3.2. Conformer dependent univariate analysis

As clearly seen in the plots with one independent variable, no linear relationship between CCM and enantioselectivity was identified. Given the previous successes correlating CCM with enantioselectivity, two hypotheses were formulated to explain why this metric failed to construct correlative relationships with enantio- selectivity. First, it is possible that CCM does not contain information regarding the conformational flexibility of molecules, which could be responsible for enantioselectivity. Second, it is possible that CCM does not describe the features of the molecules that are responsible for enantioinduction in this specific reaction. For example, there is a clear, intuitive relationship between the size of the 3,3′-substituents and enantioselectivity (Fig. 2). In other words, CCMs describe the general shape of the molecules, but the CCM may not be responsive to the size of a subunit if that subunit has the same general shape. If this is the case, one would not expect CCM alone to be a general parameter to guide catalyst optimization.

Fig. 2.

Representation of the relationship between 3,3′-substituent size and enantioselectivity.

To test the first hypothesis that conformational flexibility is important for enantioinduction, resulting in large fluctuations in CCM for each given catalyst, CCM_A and CCM_BA were calculated. Further, because the deviation in CCM value across different conformers could reflect how catalyst flexibility could influence enantioselectivity in reactions, the standard deviation and weighted standard deviation, CCM_SD and CCM_BSD, respectively, were also used as single parameters to describe enantioselectivity (Fig. 3). Unfortunately, no trend relating enantioselectivity to any of the four above parameters was identified.

Fig. 3.

Free energy plotted against conformer dependent CCM.

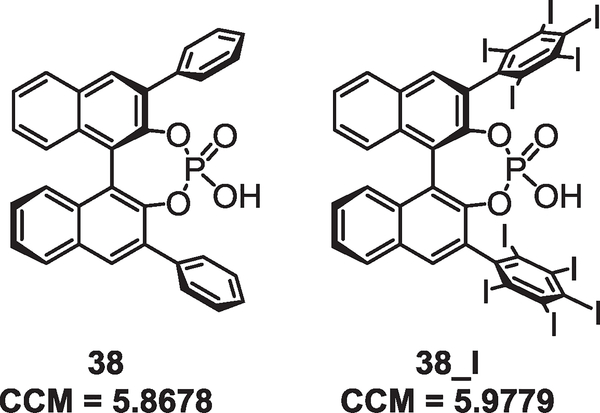

This computational experiment does not indicate that CCM_A, CCM_SD, CCM_BA, and CCM_BSD are not meaningful chemical descriptors but rather that these descriptors alone do not contain enough information about catalyst structure to predict enantioselectivity in this specific reaction. This conclusion therefore necessitates investigation of our second hypothesis that CCM may not be responsive to factors such as the size of key subunits that dictate the result of the reaction. For example, it is reasonable to postulate that the bulky triarylsilyl-substituents at the 3,3′-substituents are ineffective catalysts because they inhibit activation of the substrate by the catalyst. This effect would slow down the rate of catalyzed reaction, and the background reaction would then be dominant, explaining the formation of nearly racemic product. Because CCM is calculated with respect to the nearest achiral point group, it is reasonable to postulate that this descriptor is a representation of molecular shape; thus, it is not reasonable to suspect that CCM alone would capture this effect. To investigate this hypothesis, compounds of disparate structure but similar shape were evaluated. Compound 38 was compared with an analog in which the hydrogen atoms on the 3,3′-phenyl substituents were replaced with iodide atoms (38_I). Despite the intuitive dissimilarity between the two substituents, the calculated CCM_C2-H values are quite similar (Fig. 4, 5.8678 and 5.9779, respectively).

Fig. 4.

Differentially sized 3,3′ substituents with similar shapes give similar CCM values.

Although this crude analysis is certainly not conclusive, it lends credence to the hypothesis that CCM is related primarily to molecular shape and could be used in combination with other parameters to construct multivariate models correlating the calculable descriptors with enantioselectivity.

3.3. CCM with complementary descriptors

3.3.1. Construction of sensible, 3-D chemical space

As an initial test of the hypothesis that combining CCM descriptors with other descriptors could result in the construction of meaningful correlations with selectivity, multiple 3D chemical spaces were constructed using CCM with other descriptors to attempt to group “like” catalysts. It was reasoned that if these descriptors could be used in multivariate modeling, one should be able to use them to construct a chemical space wherein catalysts of similar selectivity values are closer than catalyst structures with different selectivity. To evaluate this hypothesis, the aforementioned CCM values were plotted with L, B1, and B5 Sterimol parameters to construct a chemical space in which similarly selective catalysts are grouped together. As seen in Fig. 5, plotting the three Sterimol parameters alone gives reasonable groupings of similarly selective catalysts. However, the selective catalysts (in blue) are in close proximity in this space to an unselective catalyst (red), indicating the chemical space constructed may not contain enough information to predict the selectivity of new catalysts in this reaction. When the B1 parameter is replaced with CCM_LE, the chemical space becomes much more well-defined, with the most selective catalysts clearly grouped together. Similarly, there are also clearly defined low and medium selectivity regions of chemical space. Thus, we reasoned that CCM could be complementary to these size descriptors as a parameter that largely describes the shape of the molecule of interest.

Fig. 5.

Catalyst space constructed from L, B1, and B5 Sterimol parameters (left) and L, B5, and CCM_LE parameters (right). The catalysts are colored by the free energy differential indicated by their experimental enantioselectivity; blue is the most selective and red is the least selective.

3.3.2. CCM as a catalyst descriptor in machine learning models

With this preliminary, qualitative indication that CCM values can enable discrimination between low, medium, and high selectivity catalysts, more quantitative measures of the contribution of these parameters to catalyst discrimination were performed. To this end, machine learning models were generated using a variety of parameters, including the different CCM values, to identify the influence of CCM on the ability of the models to predict reaction outcome. Random Forest was selected because of the capability to rank the relative importance of descriptors, providing insight into important design features in future optimization campaigns. To increase the number of data points available for model development, reactant descriptors were used to describe imines and thiols used in the transformation, including Sterimol parameters, vibrational frequencies, and NBO orbital energies, occupancies, and charges (a complete list of descriptors is available in the Supporting Information). Thus, twenty-five reactions per catalyst were used with [43] different catalysts to generate a data set of 1000 reaction outcomes for model development.

First, to evaluate the performance of CCM descriptors against widely accepted Sterimol parameters, the CCM_BA and CCM_BSD descriptors were used to describe catalyst properties in one model and Sterimol B1, B5, and L parameters were to describe catalyst properties in a separate model. A common set of substrate parameters was employed so that the only different between the feature sets was the representation of the catalyst. Because the electronic character of the 3,3′-substituents of the catalyst empirically has little influence on enantioselectivity, we reasoned that in these preliminary studies electronic effects could be neglected. However, further studies in which electronic parameters are included would be an interesting avenue of future research. Both models gave reasonable results, with Sterimol parameters outperforming CCM_BA and CCM_BSD in prediction of the external test set (Mean Absolute Deviation (MAD) = 0.199 kcal/mol and MAD = 0.255 kcal/mol, respectively, Fig. 6A and B). Both models give excellent performance, predicting enantioselectivity outcome at an accuracy rivaling that of quantum chemical methods [63]. Further, control experiments in which random features are used give no correlation, indicating chemical descriptors are indeed responsible for model efficacy (Fig. S5). Interestingly, the model in which only Sterimol parameters are used to describe catalyst structure can predict the inversion of selectivity observed with some substrate – catalyst combinations, whereas the CCM-only descriptors fail to predict this trend.

Fig. 6.

External test set predicted vs. observed plots for (A) using only CCM_BA and CCM-BSD to describe catalyst properties and (B) a random forest model generated using only Sterimol values to describe catalyst properties.

With preliminary results indicating both Sterimol and CCM are competent descriptors for the application of machine learning to asymmetric catalysis, it was postulated that combining these descriptors would lead to more accurate models. This idea was inspired by our prior hypothesis that CCM values are indicative of molecular shape, and combining these descriptors with Sterimol properties thus may provide a more holistic view of catalyst properties. Accordingly, each of the above CCM parameters (CCM_LE, CCM_C2-H, CCM_C2-A, CCM_Chiraphore, CCM_A, CCM_SD, CCM_BA, and CCM_BSD) were used with the B1, B5, and L Sterimol parameters to construct random forest models (Table 1). All combinations in which CCM parameters and Sterimol parameters are used together give more accurate predictions than when either are used independently. The model with the lowest average MAD is the model in which Sterimol and CCM_ C2-A parameters are used to describe catalyst properties (Fig. 7). However, to test if the listed descriptor combinations are significantly different from one another, a one-way ANOVA (ANalysis Of VAriance) was performed.

Table 1.

Summary of external test set MAD.

| Descriptor Combination | Run 1 MAD | Run 2 MAD | Run 3 MAD | Run 4 MAD | Run 5 MAD | Run 6 MAD | Run 7 MAD | Run 8 MAD | Run 9 MAD | Run 10 MAD | Avg. MAD (kcal/ mol) | Std. Dev. (kcal/ mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sterimol Only | 0.222 | 0.216 | 0.204 | 0.197 | 0.226 | 0.230 | 0.211 | 0.221 | 0.237 | 0.228 | 0.219 | 0.012 |

| CCM_BA and CCM_BSD only | 0.305 | 0.310 | 0.280 | 0.262 | 0.280 | 0.297 | 0.265 | 0.266 | 0.267 | 0.278 | 0.281 | 0.017 |

| Sterimol and CCM_LE | 0.183 | 0.183 | 0.183 | 0.192 | 0.193 | 0.193 | 0.185 | 0.177 | 0.184 | 0.190 | 0.186 | 0.005 |

| Sterimol and CCM_C2-H | 0.176 | 0.181 | 0.175 | 0.181 | 0.188 | 0.187 | 0.175 | 0.179 | 0.179 | 0.190 | 0.181 | 0.006 |

| Sterimol and CCM_C2-A | 0.178 | 0.170 | 0.169 | 0.173 | 0.180 | 0.181 | 0.175 | 0.173 | 0.181 | 0.178 | 0.176 | 0.005 |

| Sterimol and CCM_Chiraphore | 0.174 | 0.175 | 0.180 | 0.186 | 0.195 | 0.183 | 0.178 | 0.172 | 0.192 | 0.193 | 0.183 | 0.008 |

| Sterimol and CCM_A | 0.174 | 0.176 | 0.177 | 0.183 | 0.189 | 0.181 | 0.173 | 0.176 | 0.181 | 0.186 | 0.180 | 0.005 |

| Sterimol and CCM_SD | 0.186 | 0.190 | 0.189 | 0.195 | 0.201 | 0.190 | 0.184 | 0.184 | 0.195 | 0.196 | 0.191 | 0.006 |

| Sterimol and CCM_BA | 0.176 | 0.175 | 0.187 | 0.189 | 0.181 | 0.189 | 0.179 | 0.187 | 0.183 | 0.192 | 0.184 | 0.006 |

| Sterimol and CCM_BSD | 0.185 | 0.197 | 0.183 | 0.183 | 0.179 | 0.189 | 0.183 | 0.186 | 0.185 | 0.193 | 0.186 | 0.005 |

| Sterimol and CCM_BA and CCM_BSD | 0.178 | 0.185 | 0.176 | 0.182 | 0.184 | 0.186 | 0.178 | 0.188 | 0.190 | 0.180 | 0.183 | 0.005 |

Fig. 7.

Predicted vs. Observed Selectivity values for the Random Forest models generated with Sterimol and CCM_ C2-A used as catalyst descriptors.

Prior to performing the one-way ANOVA, the data sets were tested for normality with the D’Agostino-K squared test, with the kurtosis, skewness, and omnibus statistics indicating a normal distribution for each data set (α = 0.05). However, performing the ANOVA on the untransformed error data failed the Brown-Forsythe test of variance homogeneity. Thus, the data was transformed by the following expression:

| (2) |

In this expression, X is the original error data, n is a constant set to 0.01, and X′ is the transformed data. The variances in the transformed dataset were not significantly different as indicated by the Brown-Forsythe test (F(10,99) = 1.842, p = 0.063, α = 0.05). Further, the D’Agostino-K squared test indicated a normal distribution, satisfying the requirements of a normal distribution and homogeneity in variance between the populations. The ANOVA on the transformed data indicates that the means of one or more of the MADs associated with different descriptor sets are significantly different (F(10,99) = 130.701, p = 0.000, α = 0.05). Performing a Tukey test provides more information about the differences between the different descriptor combinations (the full summary table can be found in the Supplementary Data). The results of this analysis indicated that the descriptor set in which only Sterimol parameters were used to describe the catalyst properties was significantly more accurate than the set in which only CCM_BA and CCM_BSD were used to describe the catalyst properties. As hypothesized, every descriptor set in which a combination of CCM and Sterimol parameters were used significantly outperformed both Sterimol only and CCM_BA and CCM_BSD descriptor combinations. The Sterimol and CCM_ C2-A descriptor combination was significantly more accurate than the Sterimol and CCM_LE, Sterimol and CCM_BSD, Sterimol and CCM_SD descriptor combinations. The Sterimol and CCM_A descriptor combination was also significantly more accurate than the Sterimol and CCM_SD descriptor combination. Interestingly, all other combinations in which both a CCM-derived descriptor and Sterimol parameters were used were not significantly different from each other. Although a definitive conclusion about which CCM parameter performs best when combined with Sterimol parameters is not possible, the performance of descriptor sets including both Sterimol parameters and CCM-derived parameters yield models that are significantly more accurate than either Sterimol or CCM alone.

To ascertain the relative contributions of CCM and Sterimol values to model efficacy, the relative significance of the individual features used to construct each random forest models were analyzed. The output of this analysis is a decimal value corresponding to the significance of each feature, wherein the sum of all the importance values for all features is equal to one. The summary of the relative feature importance values is depicted in Fig. 8. In the bar graph in Fig. 8, the first category is CCM_only, in which CCM_BA and CCM_BSD (0.266 and 0.442, respectively) were used and the summation of both parameters is reported and all Sterimols values have been set to zero for comparison. Similarly, the second category is Sterimol only in which the CCM value has been set to zero. All other categories are labeled based on the method of calculation for the CCM value, but also contain Sterimol parameters. The CCM_BApBSD category uses CCM_BA, CCM_BSD, and Sterimol parameters to describe catalyst properties, and the CCM bar is the combination of both CCM_BA and CCM_BSD (0.068 and 0.084, respectively).

Fig. 8.

Top: Bar graph depicting feature importance of a CCM-derived parameter and the three Sterimol values for each random forest model generated. Bottom: Table summarizing the content of the bar graph. Note that only the relative importance of catalyst features are shown; the relative importance of substrates is not listed.

This analysis indicates that the L and B1 Sterimol parameters were especially important in predicting the enantioselectivity outcome of the reactions. However, in many cases, the CCM value is relatively significant as well; the significance of the CCM parameter was greater than the significance of the Sterimol B5 parameter in every case in which both were used to describe catalyst properties. Therefore, in this specific reaction, CCM values significantly improve the accuracy of the models and are more influential than the B5 Sterimol parameter but are less influential than the B1 and L Sterimol parameters. It is worth noting that the relative importance of these parameters should not be extended beyond this unique chemical system – other reactions may give other relative weights to each of these descriptors.

4. Conclusions

In this study we have introduced new conformer-dependent CCMs, evaluated CCM as a single parameter with which to correlate enantioselectivity for a relatively diverse set of catalyst structures, and evaluated the use of CCM as a descriptor in machine learning. For the specific model reaction used in this case study, CCM did not adequately capture the catalyst features responsible for enantioinduction. However, when CCM parameters are used with Sterimol parameters to represent catalyst properties, accurate machine learning models were constructed. Further, the combination of Sterimol parameters and CCM parameters was demonstrated to give statistically significantly more accurate models than either Sterimol or CCM parameters alone.

The major limitation of using CCM in modeling is the inherent difficulty in deriving physical meaning from the descriptor. If CCM is significant, it is difficult to use this information to identify which catalyst features are responsible for enantioinduction. It may be possible to identify the catalyst features most influential in dictating CCM by making structural perturbations to the catalyst structure and identifying how those changes correlate to CCM, thus providing a direct link to structure. However, the practitioner would be advised to validate these hypotheses with other methods, such as quantum chemical calculations, to avoid the risk of over interpretation of the results. Despite this limitation, including CCM values as a catalyst descriptor could have immediate benefits in catalyst optimization campaigns, by providing an easily accessed descriptor that is complementary to other popular descriptors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Jeremy Henle for providing code for structure generation and performing conformational searches. We thank Brennan Rose, Yang Wang, William Darrow, Zachary Wickenhauser, and Kevin Robb for experimental assistance. We thank Raquel Mendizábal Martell for insightful conversations regarding statistical analyses.

Funding sources

We are grateful for generous financial support from the W. M. Keck Foundation. A.F.Z. is grateful to the University of Illinois for Graduate Fellowships.

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tet.2019.02.007.

References

- [1].Lipkowitz K, Kozlowski M, Synlett 10 (2003) 1547. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Burello E, Rothenberg G, Int. J. Mol. Sci 7 (2006) 375. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Balcells D, Maseras F, NewJ. Chem 31 (2007) 333. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Houk KN, Cheong PH-Y, Nature 455 (2008) 309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Fey F, Orpen AG, Harvey JN, Coord. Chem. Rev 253 (2009) 704. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Corbeil CR, Moitessier N, J. Mol. Catal. A Chem 324 (2010) 146. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Fey N, Dalton Trans. 39 (2010) 296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Maldonado AG, Rothenberg G, Chem. Soc. Rev 39 (2010) 1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Neel AJ, Hilton MJ, Sigman MS, Toste FD, Nature 543 (2017) 637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Baskin II, Madzhidov TI, Antipin IS, Varnek A. Russ. Chem. Rev 86:1127. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Engkvist O, Norrby P-O, Selmi N, Lam Y-h, Peng Z, Sherer EC, Amberg W, Erhard T, Smyth LA, Drug Discov. Today 23 (2018) 1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Santiago CB, Guo J-Y, Sigman MS, Chem. Sci 9 (2018) 2398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Engel T, J. Chem. Inf. Model 46 (2006) 2267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Peter W, Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Mol. Sci 1 (2011) 46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Agrafiotis DK, Bandyopadhyay D, Wegner JK, van Vlijmen H, J. Chem. Inf. Model 47 (2007) 1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Oslob JD, Äkermark B, Helquist P, Norrby P-A, Organometallics 16 (1997) 3015. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Aires-de-Sousa J, Gasteiger J, J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci 41 (2001) 369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Aires-de-Sousa J, Gasteiger J, Gutman I, Vidovic D, J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci 44 (2004) 831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Lipkowitz K, Pradhan M, J. Org. Chem 68 (2003) 4648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Kozlowski MC, Dixon SL, Panda M, Lauri G, J. Am. Chem. Soc 125 (2003) 6614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Phuan P-W, Ianni JC, Kozlowski MC, J. Am. Chem. Soc 126 (2004) 15473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ianni JC, Annamalai V, Phuan P-W, Panda M, Kozlowski M, Angew. Chem 118 (2006) 5628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Huang J, Ianni JC, Antoline JE, Hsung RP, Kozlowski MC, Org. Lett 8 (2006) 1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Kozlowski M, Ianni J, J. Mol Catal. A. Chem 324 (2010) 141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Melville JL, Andrews BI, Lygo B, Hirst JD, Chem. Comm 0 (2004) 1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Melville JL, Lovelock KRJ, Wilson C, Allbutt B, Burke EK, Lygo B, Hirst JD, J. Chem. Inf. Model 45 (2005) 971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Denmark SE, Gould ND, Wolf LM, J. Org. Chem 76 (2011) 4260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Denmark SE, Gould ND, Wolf LM, J. Org. Chem 76 (2011) 4337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Li L, Pan Y, Lei M, Catal. Sci. Technol 6 (2016) 4450. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Yamaguchi S, Nishimura T, Hibe Y, Nagai M, Sato H, Johnston I, J. Comput. Chem 38 (2017) 1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Perrin L, Clot E, Eisenstein O, Loch J, Crabtree RH, Inorg. Chem 40 (2001) 5806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Zahrt AF, Henle JJ, Rose Y Wang W Darrow, Science (2019), 10.1126/science.aau5631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Pastor M, Cruciani G, McLay I, Pickett S, Clementi S, J. Med. Chem 43 (2000) 3233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Fontaine F, Pastor M, Sanz F, J. Med. Chem 47 (2004) 2805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Sciabola S, Alex A, Higginson PD, Mitchell JC, Snowden MJ, Morao I, J. Org. Chem 70 (2005) 9025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Urbano-Cuadrado M, Carbo JJ, Maladonado AG, Bo C, J. Chem. Inf. Model 47 (2007) 2234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Pu L, Yu HB, Chem. Rev 101 (2001) 757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Soai K, Niwa S, Chem. Rev 92 (1992) 833. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Aguado-Ullate S, Guasch L, Urbano-Cuadrado M, Bo C, Carboo JJ, Catal. Sci. Technol 2 (2012) 1694. [Google Scholar]

- [40]. See the original work for more detail on computational methods.

- [41].Axtell AT, Klosin J, Abboud KA, Organometallics 25 (2006) 5003. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Ewalds R, Eggeling EB, Hewat AC, Kamer PCJ, van Leeuwen PWNM, Vogt D, Chem.-Eur. J 6 (2000) 1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Bess EN, Sigman MS, in: Christmann M, Brase S (Eds.), Asymmetric Synthesis, Wiley-VCH Verlag & Co. KGaA, Boschstr; 12, 69469, Weinheim, Germany, 2012, pp. 363–370. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Harper KC, Sigman MS, J. Org. Chem 78 (2013) 2813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Sigman MS, Harper KC, Bess EN, Milo A, Acc. Chem. Res 49 (2016) 1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Ugi I, Bauer J, Bley K, Dengler A, Dietz A, Fontain E, Gruber B, Herges R, Knauer M, Reitsam K, Stein N, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 32 (1993) 201. [Google Scholar]

- [47].Zabrodsky H, Peleg S, Avnir D, J. Am. Chem. Soc 114 (1992) 7843. [Google Scholar]

- [48].Zabrodsky H, Peleg S, Avnir D, J. Am. Chem. Soc 11 (1993) 8278. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Zabrodsky H, Avnir D, Adv. Mol. Struct. Res 1 (1995) 1. [Google Scholar]

- [50].Zabrodsky H, Avnir D, J. Am. Chem. Soc 117 (1995) 462. [Google Scholar]

- [51].Gao D, Schefzick S, Lipkowitz K, J. Am. Chem. Soc 121 (1999) 9481. [Google Scholar]

- [52].Lipkowitz K, Schefziek S, Avnir D, J. Am. Chem. Soc 123 (2001) 6710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Alvarez S, Schefzick S, Lipkowitz K, Avnir D, Chem. Eur J 9 (2003) 5832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Lipkowitz K, Schefzick S, Chirality 14 (2002) 677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Bellarosa L, Zerbetto F, J. Am. Chem. Soc 125 (2002) 1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Handgraaf J-W, Reek JNH, Bellarosa L, Zerbetto F, Adv. Synth. Catal 347 (2005) 792. [Google Scholar]

- [57].Zayit A, Pinsky M, Elgavi H, Dryzun C, Avnir D, Chirality 23 (2011) 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Ingle GK, Mormino MG, Wojtas L, Antilla JC, Org. Lett 13 (2011) 4822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59] (a).CSM of molecular structure: https://github.com/abelcarreras/symgroup.; (b) CSM of electronic wavefunction: https://github.com/abelcarreras/WFNSYM.; (c) CSM of electron density from Gaussian Cube file: https://github.com/abelcarreras/cubesym. Related References:; Pinsky M, Dryzun C, Casanova D, Alemany P, Avnir D, J Comput Chem. 2008; 29:2712–2721, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Pinsky M, Casanova D, Alemany P, Alvarez S, Avnir D, Dryzun C, Kizner Z, Sterkin A. J Comput Chem. 2008; 29:190–7, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Casanova D, Alemany P. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2010; 12:15523–9, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Casanova D, Alemany P, Falceto A, Carreras A, Alvarez S. J Comput Chem 2013; 34:1321–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Schrödinger Release 2016–4, MacroModel, Schrodinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [61].Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Scalmani G, Barone V, Mennucci B, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Caricato M, Li X, Hratchian HP, Izmaylov AF, Bloino J, Zheng G, Sonnenberg JL, Hada M, Ehara M, Toyota K, Fukuda R, Hasegawa J, Ishida M, Nakajima T, Honda Y, Kitao O, Nakai H, Vreven T, Montgomery JA Jr., Peralta JE, Ogliaro F, Bearpark M, Heyd JJ, Brothers, Kudin KN, Staroverov VN, Kobayashi R, Normand J, Raghavachari K, Rendell A, Burant JC, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Cossi M, Rega N, Millam JM, Klene M, Knox JE, Cross JB, Bakken V, Adamo C, Jaramillo J, Gomperts R, Stratmann RE, Yazyev O, Austin AJ, Cammi R, Pomelli C, Ochterski JW, Martin RL, Morokuma K, Zakrzewski VG, Voth GA, Salvador P, Dannenberg JJ, Dapprich S, Daniels AD, Farkas O, Foresman JB, Ortiz JV, Cioslowski J, Fox DJ, Gaussian 09, Revision D.01, Gaussian, Inc, Wallingford CT, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [62].Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python, JMLR 12 (2011) 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- [63].Bahmanyar S, Houk KN, Martin HJ, List B, J. Am. Chem. Soc 125 (2003) 2475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.