Abstract

Background:

Patients with blood cancers experience high-intensity medical care near the end of life (EOL) and low rates of hospice use; attributes of goals of care (GOC) discussions may partly explain these outcomes.

Methods:

Using a retrospective cohort of blood cancer patients who received care at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and died in 2014, we assessed the potential relationship between timing, location, and involvement of hematologic oncologists in the first GOC discussion with intensity of care near the EOL and timely hospice use.

Results:

Among 383 patients, 39·2% had leukemia/myelodysplastic syndromes, 37·1% had lymphoma, and 23·7% had myeloma. 65·3% had a documented GOC discussion. Of the first discussions, 33·2% occurred >30 days before death, 34·8% in the outpatient setting, and 46·4% included a hematologic oncologist. In multivariable analyses, having the first discussion >30 days before death (OR 0·37, 95% CI [0·17, 0·81]), in the outpatient setting (OR 0·21, 95%CI [0·09, 0·50]), and having a hematologic oncologist present (OR 0·40, 95%CI [0·21, 0·77]) were associated with lower odds of intensive care unit admission ≤30 days before death. Presence of a hematologic oncologist at the first discussion (OR 3·07, 95%CI [1·58, 5·96]) was also associated with earlier hospice use ( >3 days before death).

Conclusions:

In this large cohort of blood cancer decedents, most initial GOC discussions occurred close to death and in the inpatient setting. When discussions were timely, outpatient, or involved hematologic oncologists, patients were less likely to experience intensive healthcare utilization near death and more likely to enroll in hospice.

Keywords: Goals of care discussions, blood cancers, end-of-life care

INTRODUCTION

In 2017, approximately 58,000 individuals died in the United States as a result of hematologic cancers.1 Existing literature suggests that compared to patients with solid malignancies, these patients have higher rates of intensive cancer-directed care near death (e.g. receipt of chemotherapy, acute hospitalizations, and intensive care unit admissions) and lower rates of timely hospice enrollment.2–11 While these end-of-life (EOL) outcomes raise concerns about the quality of EOL care for patients with hematologic cancers, little is known about factors that influence such care. Goals of care (GOC) discussions have been demonstrated to be a key factor that influence EOL care for patients with advanced solid malignancies; such discussions are associated with endorsed markers of high-quality EOL care such as receipt of care concordant with patients’ preferences, less intensive medical treatments near death, and greater hospice use.12–14 Accordingly, current guidelines recommend that GOC discussions should occur early in the disease course for patients with life-limiting illnesses.15, 16

Although specific attributes of GOC discussions (e.g. timing, location) have been associated with improved EOL care for patients with solid malignancies,12, 17 there are limited data for patients with blood cancers. Indeed, hematologic malignancies have several unique features compared to solid malignancies that may influence GOC discussions, as well as the potential impact of such discussions upon outcomes. For example, “life-limiting illness,” a term used to identify patients for whom EOL care is appropriate, is defined in solid malignancies as incurable disease (stage IV disease). This definition is not as easily applied to hematologic malignancies, as many patients present with disseminated disease (by virtue of extensive involvement of the hematopoietic and lymphatic systems), while still being potentially curable. Indeed, prior qualitative data from hematologic oncologists suggest that this blurred distinction between the curative and EOL phase for blood cancers may delay initiation of GOC discussions.18

A rigorous characterization of GOC discussions for patients with blood cancers and their impact on EOL care is needed to improve EOL care for this patient population. We aimed to characterize attributes of GOC discussions and their association with EOL care for a cohort of patients who died of blood cancers. Given the high rates of intensive medical care utilized by this population near the end of life,2, 6, 10 we hypothesized that GOC discussions would mostly occur inpatient and often near death.

METHODS

We assembled a retrospective cohort of blood cancer decedents from the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (DFCI), Boston, MA, using the DFCI Oncology Data Retrieval System (OncDRS). OncDRS is a data repository that contains information on consecutive patients who receive their care at DFCI including demographic, clinical, diagnostic, treatment, and vital statistics data. Adult patients who were 18 years or older at time of diagnosis of blood cancer and died between January 1 and December 31, 2014 were eligible for inclusion. Eligible patients also had to receive their primary oncologic care at the study institution (defined as ≥ 2 outpatient visits) in order to enhance completeness of medical data. Given that many EOL quality measures are assessed in the last 30 days of life,2, 19 we also required that eligible patients survive at least 30 days after their diagnosis. This study was approved by the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Institutional Review Board.

Medical records of the study cohort (from the first visit at the study institution through death) were manually reviewed by members of the study team (A.M and O.O) using a standardized abstraction form. Using a prior definition scheme for identifying GOC discussions from medical record data,20 we classified patients as having had a GOC discussion if there was any documentation in the medical record of a discussion regarding resuscitation status, hospice, or preferred location for dying. Prognostic discussions that occurred in the context of conversations about preferences regarding resuscitation status, hospice, or preferred location of death were subsumed under the definition of GOC discussions; however, stand-alone prognostic disclosures were not captured as GOC discussions as they may not be directly associated with clarifying goals of care.21 Importantly, given that every inpatient admission requires a code status order, inpatient notes that only documented: “Code status: Full,” without any reference to a discussion were not considered to represent GOC discussions. Although Medical Power of Attorney (MPOA) has been included in some studies of GOC discussions, we did not include it in the current study given data showing no significant relationship between MPOA completion and EOL care.22

We considered the earliest documented discussion in the medical record to be the first GOC discussion. For the first GOC discussion, we abstracted the date, topics discussed, providers involved in the discussion, whether the patient was involved in the discussion (versus caregivers only), and location of the discussion (inpatient versus outpatient). Hematologic oncologists were considered to be part of the first discussion if the GOC documentation was authored and signed by them or if they were noted to be present during the discussion even if the referenced documentation was not authored or signed by them.

Outcomes and Covariates

The primary outcome of interest was intensity of medical care at the EOL. We assessed intensity of EOL care using three indicators namely, (a) chemotherapy receipt within 14 days of death, (b) at least one intensive care unit (ICU) admission within 30 days of death, and (c) death in a hospital. These measures are widely endorsed in oncology2, 19, 23 and were recently shown to be acceptable to hematologic oncologists.24 The presence of any of these three indicators was considered high-intensity medical care at the EOL. The secondary outcome was hospice enrollment more than three days before death. Covariates included patient demographic data including age, sex, race, marital status and clinical data such as cancer type, and presence of previous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HCT).

Statistical Analysis

After characterizing the prevalence and attributes of GOC discussions (timing relative to death [> 30 days vs. ≤ 30 days], location [outpatient vs. inpatient], and presence of a hematologic oncologist) and EOL care (intensity of medical care and hospice use), we investigated the association between the attributes of the first documented GOC discussion and EOL care. For each intensity indicator of EOL care and hospice stay greater than 3 days, Chi-square test was used to assess the association with each attribute of first GOC discussion. The degree of association was summarized by odds ratio and corresponding 95% confidence interval. We also created multivariable logistic regression models for indicators of intensive medical care and the indicator of hospice use more than 3 days before death, in which associations with attributes of GOC discussions were examined jointly. We included the three attributes of first GOC discussion (timing, location, and presence of hematologic oncologist) in all multivariable models, where we adjusted for patient characteristics with p<0·05 in bivariate analyses. Age was included in all multivariable models regardless of significance in bivariate analysis, as we expected it to be a potential cofounder of EOL outcomes based on prior literature.2, 25 All significance testing was 2-sided with alpha level of ·05. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9·4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

We identified 383 consecutive deceased blood cancer patients that met eligibility for this analysis; 39·2% had leukemia/myelodysplastic syndromes, 37·1% had lymphoma, and 23·7% had myeloma. 40·7% had undergone a HCT. Other patient characteristics are listed in Table 1. Overall, 250 (65·3%) had a documented GOC discussion. Characteristics of the 250 patients were similar to the total cohort. The median time between first documented discussion and death was 15 days (interquartile range 5, 48), with 33·2% of first discussions occurring > 30 days before death, and the minority occurring in the outpatient setting (34·8%). 46·4% of all first documented discussions included a hematologic oncologist. When the discussion included a hematologic oncologist, it was most commonly the patient’s primary hematologic oncologist (81.9%). For the first documented discussions where a hematologic oncologist was not present, the involved providers included medical residents/fellows (20.0%), attending physicians/hospitalists (12.0%), palliative care specialists (7.2%), nurses (6.4%), social workers (4.4%), and physician assistants (2.8%). The most commonly discussed topic in the first documented GOC discussion was resuscitation preferences (81·2%), followed by hospice (32·4%); preferred location for dying was rarely discussed (4·0%). Other characteristics of documented GOC discussions are reported in Table 2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients

| Characteristic | Total Cohort N = 383 N (%) |

GOC discussion present N =250 N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 215 (56·1) | 133 (53·2) |

| Age | ||

| < 60 years | 112 (29·2) | 80 (32·0) |

| ≥ 60 years | 271 (70·8) | 170 (68·0) |

| Race | ||

| White | 344 (89·8) | 225 (90·0) |

| Nonwhite | 28 (7·3) | 19 (7·6) |

| Did not report race | 11 (2·9) | 6 (2·4) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 251 (65·5) | 162 (64·8) |

| Other | 132 (34·5) | 88 (35·2) |

| Diagnosis | ||

| Leukemia/myelodysplastic syndromes/myeloproliferative neoplasms | 150 (39·2) | 109 (43·6) |

| Lymphoma | 142 (37·1) | 94 (37·6) |

| Myeloma | 91 (23·7) | 47 (18·8) |

| S/p hematopoietic stem cell transplant | ||

| Yes | 156 (40·7) | 109 (43·6) |

| No | 227 (59·3) | 141 (56·4) |

Table 2.

Characteristics of first documented GOC discussions (N=250)

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Timing of discussion | |

| Within 30 days of death | 167 (66·8) |

| More than 30 days before death | 83 (33·2) |

| Location of discussion | |

| Inpatient | 163 (65·2) |

| Outpatient | 87 (34·8) |

| Hematologic oncologist involved in discussion | |

| Yes | 116 (46·4) |

| No | 134 (53·6) |

| Content of Discussion† | |

| Resuscitation status | 203 (81·2) |

| Hospice | 81 (32·4) |

| Preferred place of death | 10 (4·0) |

| Patient was part of discussion | |

| Yes | 203 (81·2) |

| No (i.e. surrogate was the one involved in discussion) | 47 (18·8) |

Categories are not mutually exclusive

With respect to EOL care, almost half (49·6%) of the total cohort experienced at least one indicator of intensive medical care. Specifically, 17·0% of patients received chemotherapy within the last 14 days of life, 21·7% had at least one ICU admission in the last 30 days of life, and 38·1% died in a hospital. About a quarter (24·3%) received hospice care and the median time spent in hospice was 8 days (interquartile range 4, 18). Of the entire cohort, 69 patients (18·0%) enrolled in hospice > 3 days before death.

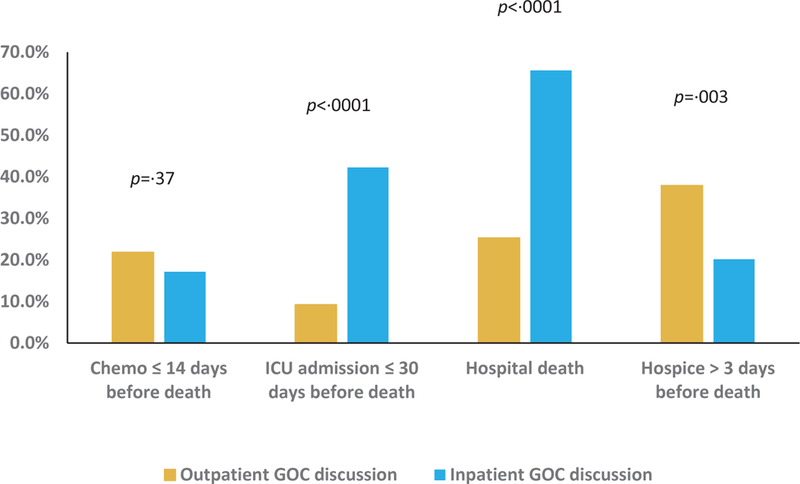

Among the subset of patients who had GOC discussions (n=250), 77 patients were admitted to the ICU within the last 30 days of life. In bivariate analyses, patients who had the first discussion more than 30 days before death were significantly less likely to have an ICU admission in the last 30 days of life (13·3% vs. 39·5%, p<0·0001; unadjusted OR=0·23 [95% CI 0·12 to 0·47]). Similarly, having the first GOC discussion in the outpatient setting (9·2% vs. 42·3%, p<0·0001; unadjusted OR =0·14 [95% CI 0·06 to 0·30]) and having a hematologic oncologist present at the first discussion (19·0% vs. 41·0%, p=0·0002; unadjusted OR=0·34 [95% CI 0·19 to 0·60]) were each associated with a lower likelihood of ICU admission in the last 30 days of life (Figures 1–3, Supplemental Table 1). These associations persisted in multivariable analyses, with timely GOC discussions, outpatient discussions, and involvement of hematologic oncologists associated with significantly lower odds of ICU admission close to death (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Timing of first GOC discussion and EOL Care

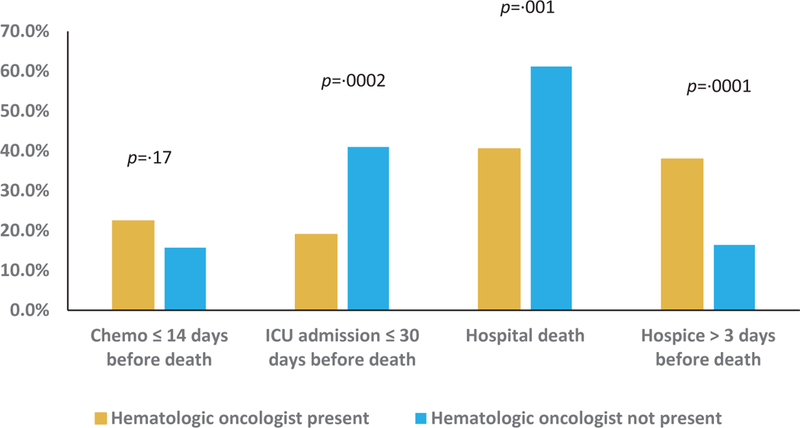

Figure 3.

Presence of hematologic oncologist at first GOC discussion and EOL care

Table 3.

Multivariable analyses of associations between attributes of first GOC discussion and EOL care†

| Characteristic |

ICU admission

≤ 30 days before death‡ |

Dying in a hospital§ |

Hospice care >

3 days before death¶ |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Timing | ||||||

| ≤ 30 days before death | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| > 30 days before death | 0·37 | 0·17, 0·81 | 0·59 | 0·31, 1·11 | 1·51 | 0·79, 2·90 |

| Location | ||||||

| Inpatient | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Outpatient | 0·21 | 0·09, 0·50 | 0·26 | 0·13, 0·53 | 1·50 | 0·76, 2·95 |

| Hematologic oncologist present | ||||||

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Yes | 0·40 | 0·21, 0·77 | 0·54 | 0·29, 0·99 | 3·07 | 1·58, 5·96 |

Separate multivariable logistic regression models fit for each outcome (ICU admission, dying in a hospital, and hospice care > 3 days before death). Each model was adjusted for age and other patient characteristics with p <0·05 in bivariate analyses.

Adjusted for age, sex, and previous HCT

Adjusted for age, sex, previous HCT, and diagnosis

Adjusted for age and sex

Among patients who had a documented GOC discussion, 51·6% died in a hospital. Patients who had the first GOC discussion more than 30 days before death were less likely to die in a hospital (34·9% vs. 59·9%, p=0·0002; unadjusted OR=0·36 [95% CI 0·21, 0·62]; Figure 1). Similarly, patients whose first GOC discussions took place in the outpatient setting were less likely to have a hospital death (25·3% vs. 65·6%, p<0.0001; unadjusted OR 0·18 [95% CI 0.10 to 0·32]; Figure 2), as were patients who had a hematologic oncologist present at their first GOC conversation (40·5% vs. 61·2%, p=0·001; unadjusted OR =0·43 [95% CI 0·26 to 0·72]; Figure 3, Supplemental Table 2). In multivariable analyses, outpatient location and involvement of a hematologic oncologist in the first GOC discussion remained significantly associated with lower odds of dying in a hospital (Table 3). Finally, with respect to high-intensity medical care near death, 18·8% of those who had a documented GOC discussion received chemotherapy within the last 14 days of life. We observed no significant differences in chemotherapy receipt close to death based on timing or location of first GOC discussion, or the presence of a hematologic oncologist (Figure 1–3, Supplemental Table 3).

Figure 2.

Location of first GOC discussion and EOL care

66 patients among those who had a documented GOC discussion enrolled in hospice more than three days before death. In unadjusted analyses, patients who had their first GOC discussion more than 30 days before death were more likely to enroll in hospice for more than 3 days (34·9% vs. 22·2%, p =0·04; unadjusted OR=1·89 [95% CI 1·06 to 3·37]). Patients who had the first GOC discussion in the outpatient setting (37·9% vs. 20·2%, p=0·003; unadjusted OR= 2·41 [95% CI 1·35 to 4·29]) or had a hematologic oncologist present (37·9% vs. 16·4%, p = 0·0001; unadjusted OR=3·11 [95% CI 1·72 to 5·62]) were also significantly more likely to enroll in hospice for more than 3 days (Figures 1–3, Supplemental Table 4). In multivariable analyses, having a hematologic oncologist present at the first GOC discussion was the only attribute that remained significantly associated with earlier hospice enrollment (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

In this large cohort of patients who died of hematologic cancers, most initial GOC discussions occurred close to death, in the inpatient setting, and almost half involved a hematologic oncologist. When GOC discussions occurred greater than one month before death, in the outpatient setting, or involved a hematologic oncologist, patients were more likely to experience less intensive cancer-directed care close to death and were more likely to enroll in hospice greater than three days before death. Taken together, our findings suggest that interventions that engage hematologic oncologists and optimize timing and location of GOC discussions are urgently needed.

Given that intensity of medical care and hospice use near the EOL differ significantly between patients with blood cancers and those with solid malignancies,2, 6, 10 we expected a lower incidence of GOC discussions among patients with blood cancers compared to what is documented in the literature for patients with solid malignancies. It was thus interesting that the rate of GOC discussions observed (65·3%) is similar to what has been reported in studies of patients who died from solid malignancies (64·5% to70·3%).12, 20 This suggests that the presence of documented GOC discussions is not sufficient to explain differences in quality of EOL care between patients with blood cancers and solid malignancies. Indeed, the attributes of GOC conversations—such as timing, location, and by whom such discussions are initiated—may play more powerful roles.

National guidelines recommend that GOC discussions should occur early in the course of illness.15,16 Contrary to these guidelines, most first documented GOC discussions in this cohort of blood cancer decedents occurred close to death. This finding is consistent with results from a national survey of hematologic oncologists where the majority reported that EOL discussions for patients with blood cancers typically occur “too late.”26 The potential curability of many blood cancers even at advanced stages and the continuing likelihood of response to multiple lines of treatment may contribute to clinicians deferring GOC discussions until death is imminent. Although the heightened level of prognostic uncertainty for hematologic malignancies may obscure the optimal time to initiate GOC discussions, waiting until there is certainty about the proximity of death limits the time to honor patients’ wishes regarding EOL care. The limited impact of late conversations is supported by our finding that GOC discussions which occurred within 30 days of death were significantly associated with higher rates of intensive medical care close to death.

Our finding that almost two-thirds of all first GOC discussions occurred in hospitals suggests that acute medical decompensation prompts clinicians to clarify preferences regarding EOL care with their patients. Unfortunately, such discussions often represent “crisis” conversations where patients already close to death are unable to fully articulate their goals. To align care with national recommendations that GOC discussions should ideally begin in the outpatient setting,16, 27 interventions coupled to triggers/prompts that can be identified in the outpatient setting are needed. On the other hand, the high rate of inpatient GOC discussions observed may also reflect the involvement of a larger medical team in the hospital setting and more opportunities to introduce GOC discussions. Indeed, inpatient clinicians who do not have longstanding relationships with blood cancer patients may be less hesitant to initiate these conversations as close long-term physician-patient relationships have been associated with avoidance of GOC discussions.28

Although slightly less than half of initial GOC conversations included hematologic oncologists, their presence was the single attribute associated with both lower rates of intensive medical care near death (ICU admission and hospital death) and higher rates of timely hospice use. Along with infusion nurses, hematologic oncologists are often the most trusted companions for patients and families on their blood cancer journey. Patients are also more likely to accept recommendations from hematologic oncologists than new or transient members of their medical team. In addition, the fact that the variable “hematologic oncologist” included both patients’ primary hematologic oncologists and other hematologic oncologists suggests that the associations observed may be a combination of patient relationship with their hematologic oncologist and trust in the specialty. While timely referral to specialty palliative care can improve EOL outcomes,29, 30 our findings demonstrate that active engagement of hematologic oncologists in GOC conversations is also important. To make meaningful strides in improving GOC discussions and EOL care for patients with blood cancers, interventions that engage hematologic oncologists are essential.

This study has limitations. First, although we performed detailed medical record abstraction, the observed rate of GOC discussions may be an underestimate as some discussions may not be documented. Moreover, although we abstracted details and content of first GOC conversations, the retrospective nature and reliance on medical documentation precluded our ability to ascertain the overall quality of communication or level of patient understanding. Second, the single-center design as well as the lack of racial/ethnic diversity may limit the generalizability of our findings. On the other hand, patients with advanced hematologic malignancies often receive care in tertiary centers like ours. In addition, other designs (e.g. claims-based large database analyses) would not have the level of granularity needed for our analysis. Third, the retrospective nature of this study precludes ascertainment of level of prognostic uncertainty. As such, we are not able to determine whether correlations existed between clinicians’ views of prognostic uncertainty for each patient and attributes of first GOC discussions. Nonetheless, current recommendations emphasize the need for timely discussion even in settings of high prognostic uncertainty.16, 31

Next, we were not able to interview patients and bereaved caregivers to assess the impact of the attributes of GOC discussions on their decision-making. Indeed, some patients who received intensive cancer-directed care close to death and did not enroll in hospice may have preferred such care even if they engaged in GOC discussions in a timely fashion. Finally, while our study demonstrates associations between attributes of GOC discussions and EOL care, it cannot firmly establish causation. Despite the aforementioned limitations, this study provides important data to inform the development of intervention studies to formally test the effects of attributes of GOC discussions on EOL care for patients with blood cancers.

Given the high rates of intensive medical care close to death and low enrollment in hospice for patients with blood cancers,2, 10, 32, 33 a concerted focus on improving quality of EOL care for this population is needed. Having more GOC discussions is necessary but not sufficient. In the report, “Dying in America,” the Institute of Medicine concludes that a “person-centered… approach that honors individual preferences and promotes quality of life through the EOL should be a national priority.”34 This can be difficult to translate into clinical practice. Our data suggest that one way to promote such person-centered care that honors individual preferences of blood cancer patients at the EOL is through timely GOC conversations that occur in the outpatient setting and importantly, involve hematologic oncologists.

Supplementary Material

Key Sentences.

In this cohort of blood cancer decedents, most initial goals of care discussions occurred ≤30 days before death or in the inpatient setting.

Discussions that were timely, outpatient, or involved hematologic oncologists were associated with lower rates of intensive healthcare utilization near death and higher rates of early hospice enrollment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

O.O. Odejide received research support from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (NCI K08 CA218295), National Palliative Care Research Center Career Development Award, and Harvard Medical School Office for Diversity Inclusion and Community Partnership Faculty Fellowship.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: No relevant financial conflict of interest

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68: 7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Earle CC, Landrum MB, Souza JM, Neville BA, Weeks JC, Ayanian JZ. Aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life: is it a quality-of-care issue? J Clin Oncol. 2008;26: 3860–3866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ho TH, Barbera L, Saskin R, Lu H, Neville BA, Earle CC. Trends in the aggressiveness of end-of-life cancer care in the universal health care system of Ontario, Canada. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29: 1587–1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sexauer A, Cheng MJ, Knight L, Riley AW, King L, Smith TJ. Patterns of hospice use in patients dying from hematologic malignancies. J Palliat Med. 2014;17: 195–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Odejide OO, Cronin AM, Earle CC, LaCasce AS, Abel GA. Hospice Use Among Patients With Lymphoma: Impact of Disease Aggressiveness and Curability. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Connor NR, Hu R, Harris PS, Ache K, Casarett DJ. Hospice admissions for cancer in the final days of life: independent predictors and implications for quality measures. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32: 3184–3189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tang ST, Wu SC, Hung YN, Chen JS, Huang EW, Liu TW. Determinants of aggressive end-of-life care for Taiwanese cancer decedents, 2001 to 2006. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27: 4613–4618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.LeBlanc TW, Egan PC, Olszewski AJ. Transfusion dependence, use of hospice services, and quality of end-of-life care in leukemia. Blood. 2018;132: 717–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Howell DA, Wang HI, Smith AG, Howard MR, Patmore RD, Roman E. Place of death in haematological malignancy: variations by disease sub-type and time from diagnosis to death. BMC Palliat Care. 2013;12: 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hui D, Didwaniya N, Vidal M, et al. Quality of end-of-life care in patients with hematologic malignancies: a retrospective cohort study. Cancer. 2014;120: 1572–1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.El-Jawahri AR, Abel GA, Steensma DP, et al. Health care utilization and end-of-life care for older patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer. 2015;121: 2840–2848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mack JW, Cronin A, Keating NL, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussion characteristics and care received near death: a prospective cohort study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30: 4387–4395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mack JW, Weeks JC, Wright AA, Block SD, Prigerson HG. End-of-life discussions, goal attainment, and distress at the end of life: predictors and outcomes of receipt of care consistent with preferences. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28: 1203–1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300: 1665–1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levy MH, Smith T, Alvarez-Perez A, et al. Palliative Care, Version 1.2014. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2014;12: 1379–1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilligan T, Coyle N, Frankel RM, et al. Patient-Clinician Communication: American Society of Clinical Oncology Consensus Guideline. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2017;35: 3618–3632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lopez-Acevedo M, Havrilesky LJ, Broadwater G, et al. Timing of end-of-life care discussion with performance on end-of-life quality indicators in ovarian cancer. Gynecologic Oncology. 2013;130: 156–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Odejide OO, Salas Coronado DY, Watts CD, Wright AA, Abel GA. End-of-life care for blood cancers: a series of focus groups with hematologic oncologists. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10: e396–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Quality Forum. National Voluntary Consensus Standards: Palliative Care and End-of-Life Care: A Consensus Report. Available from URL: http://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2012/04/Palliative_Care_and_End-of-Life_Care%e2%80%94A_Consensus_Report.aspx [accessed August 1, 2019].

- 20.Mack JW, Cronin A, Taback N, et al. End-of-life care discussions among patients with advanced cancer: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156: 204–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alexander SC, Sullivan AM, Back AL, et al. Information giving and receiving in hematological malignancy consultations. Psychooncology. 2012;21: 297–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Narang AK, Wright AA, Nicholas LH. Trends in Advance Care Planning in Patients With Cancer: Results From a National Longitudinal Survey. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1: 601–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.American Society of Clinical Oncology. Quality Oncology Practice Initiative. The Quality Oncology Practice Initiative Quality Measures. Available from URL: http://www.instituteforquality.org/qopi/measures [accessed August 1, 2019, 2019].

- 24.Odejide OO, Cronin AM, Condron NB, et al. Barriers to Quality End-of-Life Care for Patients With Blood Cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34: 3126–3132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Earle CC, Neville BA, Landrum MB, Ayanian JZ, Block SD, Weeks JC. Trends in the aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22: 315–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Odejide OO, Cronin AM, Condron N, Earle CC, Wolfe J, Abel GA. Timeliness of End-of-Life Discussions for Blood Cancers: A National Survey of Hematologic Oncologists. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176: 263–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dans M, Smith T, Back A, et al. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Palliative Care, Version 2.2017. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2017;15: 989–997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Christakis NA, Lamont EB. Extent and determinants of error in doctors’ prognoses in terminally ill patients: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2000;320: 469–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hui D, Kim SH, Roquemore J, Dev R, Chisholm G, Bruera E. Impact of timing and setting of palliative care referral on quality of end-of-life care in cancer patients. Cancer. 2014;120: 1743–1749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363: 733–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Temel JS, Shaw AT, Greer JA. Challenge of Prognostic Uncertainty in the Modern Era of Cancer Therapeutics. J Clin Oncol. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang R, Zeidan AM, Halene S, et al. Health Care Use by Older Adults With Acute Myeloid Leukemia at the End of Life. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35: 3417–3424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fletcher SA, Cronin AM, Zeidan AM, et al. Intensity of end-of-life care for patients with myelodysplastic syndromes: Findings from a large national database. Cancer. 2016;122: 1209–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Institute of Medicine. Dying in America: Improving quality and honoring individual preferences near the end of life. Washington, DC: The national Academies Press, 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.