Abstract

Objective:

Racial discrimination is a stressor that may put African Americans at risk for alcohol use and related problems. We examined whether experiences of blatant (racist events) and subtle (racial microaggressions) forms of racial discrimination were associated with alcohol consumption and alcohol problems among African American young adults, and whether childhood/adolescence racial socialization by parents and friends moderated these associations.

Method:

The sample included 383 African American young adults (Mage = 20.65, SD = 2.28; 81% female) who completed an electronic survey in Fall, 2017. Hierarchical linear regression analyses were conducted in Mplus.

Results:

Experiences of racist events and racial microaggressions were associated with higher levels of alcohol consumption and more alcohol problems. Racial socialization by friends, but not parents, moderated these associations. Specifically, cultural socialization by friends buffered the effect of racist events on alcohol consumption and alcohol problems, whereas promotion of mistrust by friends exacerbated the effect of racial microaggressions on alcohol problems.

Conclusions:

Both blatant and subtle forms of racial discrimination were associated with higher risk for alcohol use/problems among African American young adults. Racial socialization by friends while growing up may play an important role in alcohol use outcomes during young adulthood. Findings highlight the importance of considering different forms of racial discrimination and emphasize the unique roles of racial socialization across different social contexts (i.e., parent and peers/friends) in relation to psychosocial outcomes among African American individuals.

Keywords: racial discrimination, microaggressions, racial socialization, alcohol use, African Americans

Alcohol use is prevalent in the U.S., with risk for alcohol use disorders peaking during young adulthood (Grant et al., 2015; Sacks, Gonzales, Bouchery, Tomedi, & Brewer, 2015). College students are more likely to drink heavily and develop alcohol use disorders than their non-college-attending peers (Barnes, Welte, Hoffman, & Tidwell, 2010; Slutske et al., 2004). College students face unique socioenvironmental changes and transitions, such as leaving home and forming new peer groups, which usually create increased opportunity for alcohol involvement and exposure to stress that lead to elevated risk for alcohol problems (Evans, Forney, Guido, Renn, & Patton, 2010). Although African Americans, on average, consume less alcohol than European Americans, they tend to suffer more negative social and health consequences related to alcohol use (Chartier & Caetano, 2010; Mulia et al., 2009). Thus, understanding risk and protective factors underlying alcohol problems in African American college students is important for prevention and intervention efforts.

Racial Discrimination and Alcohol Consumption and Problems

Theoretical models of racial/ethnic minority individuals’ health posit that race-related stressors, including perceived discrimination, influence individuals’ general health and well- being, in part by inducing heightened psychological stress responses (Garcia Coll et al., 1996; Meyers, 2009; Pascoe & Richman, 2009; Spencer, 2006). For example, the phenomenological variant of ecological systems theory (PVEST) posits that vulnerability factors, such as racial discrimination, increase individuals’ risk for negative, unproductive outcomes such as alcohol problems (Spencer, 2006). Previous research indicates that perceived racial discrimination is a common experience among African Americans and is associated with health behaviors and psychosocial functioning (Benner et al., 2018; Harrell, 2000; Priest et al., 2013; Williams & Mohammed, 2009), including more frequent and greater quantity of alcohol consumption and more alcohol problems, such as interference with work and life responsibilities and inability to reduce drinking (Boynton, O’Hara, Covault, Scott, & Tennen, 2014; Latzman, Chan, & Shishido, 2013; Lee, Heinze, Neblett, Caldwell, & Zimmerman, 2017).

Racial discrimination can occur in different forms. Some experiences are blatant and explicit, such as verbal insults and police brutality (Landrine & Klonoff, 1996), while others are more subtle, such as microaggressions and antagonism against promotion of equity (Nadal, 2011). The distinction between blatant versus subtle forms of racial discrimination is important because they can have different effects on targets of discrimination (Major, Quinton, & McCoy, 2002; Major & Dover, 2016). When people experience blatant forms of racism, it is easy for them to attribute their negative experience to discrimination, which is an external factor. In contrast, when people experience subtle forms of racism, a cause of such negative experience can be ambiguous: some people attribute subtle forms of racism to discrimination, while others attribute the same racism to characteristics internal to them, such as personality flaw, lack of ability or skills. This “situational ambiguity” is important in relation to attributions to discrimination, with important implications for individuals’ psychosocial well-being (Major et al., 2002; Major & Dover, 2016). When individuals attribute negative experiences and events to discrimination, they experience increased psychological and physiological stress responses, which may increase their risk of using alcohol to cope.

Prior research linking racial discrimination and alcohol use outcomes have primarily focused on blatant racial discrimination (Gilbert & Zemore, 2016). However, an emerging literature has indicated that experience of subtle racial discrimination, particularly microaggressions, is also related to increased risk for emotional challenges and substance use, including depression and negative affect (Nadal, Griffin, Wong, Hamit, & Rasmus, 2014), marijuana use (Pro, Sahker, & Marzell, 2017), and binge drinking and alcohol problems (Blume, Lovato, Thyken, & Denny, 2012). Prior research did not distinguish different forms of racial discrimination, and it is unclear whether the influences of blatant versus subtle forms of racial discrimination on alcohol use outcomes are similar or different. Understanding the associations between different forms of racial discrimination and alcohol use outcomes is critical for developing effective interventions.

The Role of Parental and Peer Racial Socialization

The PVEST (Spencer, 2006) posits that not only do vulnerability factors impact unproductive outcomes, but protective factors are expected to buffer the effects of vulnerability factors. Thus, it is possible that protective factors, such as racial socialization, may protect against the negative effects of racial discrimination on alcohol use outcomes. Indeed, racial socialization in families is theorized to moderate the relationship between racial stress and self- efficacy in a path to coping and well-being (Anderson & Stevenson, 2019). Parental racial socialization refers to parental practices that convey messages about race and ethnicity to offspring (Hughes et al., 2006; Hughes, Watford, & Toro, 2016). Racial socialization is conceptualized as involving various components, including parents’ efforts to instill pride in and knowledge about children’s racial/ethnic group (i.e., cultural socialization), discussions about racial bias and coping strategies (i.e., preparation for bias), and to a lesser extent, the promotion of mistrust of other racial groups (Hughes et al., 2006).

Racial socialization has been primarily studied with adolescents in previous research. Cultural socialization has been shown to be associated with better psychosocial well-being among African Americans, including higher self-esteem, and fewer depressive symptoms among adolescents and young adults (Dunbar et al., 2015; Reynolds & Gonzales-Backen, 2017), and lower alcohol and substance use among adolescents (Grindal & Nieri, 2016; Zapolski, T., & Clifton, 2018). Preparation for bias has been conceptualized as protective and beneficial (Hughes et al., 2006; Hughes, Watford, & Toro, 2016). However, some studies showed that preparation for bias may be associated with poor psychosocial outcomes among African American adolescents, such as more internalizing and externalizing problems (Caughy, O’Campo, Nettles, & Lohrfink, 2006) and more antisocial behaviors (Hughes, Witherspoon, Rivas-Drake, & West-Bey, 2009), possibly due to unintentionally generated anxiety and vulnerability that accompanied awareness of discrimination (Hughes et al., 2009). Finally, although a less common racial socialization practice, promotion of mistrust is a risk factor for poorer psychosocial outcomes among African American youth (Hughes et al., 2006), including higher risk for substance use among adolescents (Grindal & Nieri, 2016).

To our knowledge, there are only two published studies that examined the role of racial socialization in relation to alcohol and substance use outcomes among African American college students or adults. In a sample of African American adults living in predominantly Black neighborhoods in New York City, racial socialization (measured as a composite of racial socialization from parents, peers, and other adults) in childhood and adolescence was not associated with alcohol consumption, problematic alcohol use, and tobacco use (Thompson, Goodman, & Kwate, 2016). In another sample of African American college students, racial socialization by parents was also not associated with alcohol and substance use (Bowman Heads, Glover, Castillo, Blozis, & Kim, 2018). Notably, neither of these studies examined the effects of specific dimensions of racial socialization on alcohol and substance use outcomes.

In addition to the direct effects on mental health and substance use outcomes, theoretical writings and empirical evidence suggests that racial socialization also buffers or exacerbates the negative health and behavioral consequences of racial discrimination, depending on the specific racial socialization practices (Neblett, Terzian, & Harriott, 2010). Cultural socialization practices that promote racial pride have been shown to buffer the effect of racial discrimination on adolescent outcomes such as crime (Burt, Simons, & Gibbons, 2012), self-esteem (Harris-Britt, Valrie, Kurtz-Costes, & Rowley, 2007), and psychological well-being, particularly in a context of supportive parental involvement (Varner et al., 2018). Findings regarding the moderating effect of preparation for bias have been mixed. Some studies found that higher preparation of bias buffered the negative effect of racial discrimination (Burt et al., 2012); others found that only moderate levels of preparation of bias is protective, and low or high levels of preparation of bias exacerbated the negative influence of racial discrimination (Harris-Britt et al., 2007). Yet, others found no moderating effect of parental racial socialization practices, including both cultural socialization and preparation for bias, on the associations between racial discrimination and African American adolescents’ psychosocial outcomes (Dotterer, McHale, & Crouter, 2009). To our knowledge, there is very little research examining the moderating effect of promotion of mistrust on the relationship between racial discrimination and psychosocial outcomes.

A few studies that examined the moderating role of racial socialization on the relations between racial discrimination and psychosocial outcomes among college students and young adults yielded null findings. For example, Bynum, Burton, and Best (2007) found that parental racial socialization that promotes cultural pride or coping with racism did not buffer the relation between racism experiences and psychological distress among African American college freshmen. Thompson and colleagues (2016) found that racial socialization did not moderate the effects of racial discrimination on alcohol and substance use among African American adults. These findings suggest that racial socialization by parents may not be a salient protective factor for college students and young adults. However, no research has examined whether and how moderating effects of racial socialization practices may differ for different forms of racial discrimination. For example, preparation for bias and promotion of mistrust may be particularly relevant for exacerbating the influence of subtle forms of discrimination by increasing awareness of and attribution to discrimination (Hughes et al., 2009).

The majority of previous studies focus on racial socialization by parents, with limited attention to other important socialization agents such as peers (Nelson, Syed, Tran, Hu, & Lee, 2018). Peers play an important role in individuals’ development, including the development of alcohol use and problems (Oetting & Donnermeyers, 1998). In fact, peers are the most robust influence on alcohol use behaviors during adolescence and young adulthood (Schulenberg & Maggs, 2002), although parents continue to play an important role in influencing individuals’ alcohol use in college (Abar & Turrisi, 2008; Fairlie, Wood, & Laird, 2012). Researchers have called for the considerations of racial socialization across multiple developmental contexts (i.e., family and peer) in understanding the well-being of racial/ethnic minority populations (Wang & Benner, 2016; Wang, Benner, & Kim, 2015). Prior research indicates that parental racial socialization often occurs in the context of high parental warmth and support and is more influential for youth outcomes in the context of higher parent-child relationship quality (Cooper & McLoyd, 2011; Small, 2010; Smith-Bynum, Anderson, Davis, Franco, & English, 2016; Small, 2010). The context in which peer racial socialization occurs remains understudied, and the potential mechanisms for the influence of racial socialization by friends on alcohol use could be similar or distinct from those for racial socialization by parents. Given prior evidence of parental and peer influence, as well as the important role of racial socialization on alcohol use, it is important to study the role of racial socialization by both parents and friends while growing up in influencing individuals’ alcohol use outcomes.

The Present Study

The goal of this study was to examine 1) whether blatant (i.e., racist events) and subtle (i.e., microaggressions) forms of racial discrimination are associated with alcohol consumption and alcohol problems in African American young adults, 2) how three types of racial socialization (i.e., cultural socialization, preparation for bias, and promotion of mistrust) in childhood/adolescence by parents and friends are associated with alcohol use outcomes, and 3) whether parent and friend racial socialization practices moderate the associations between racial discrimination and alcohol use outcomes. We considered both alcohol consumption and alcohol problems because prior research suggests that etiological pathways may differ for them. Specifically, alcohol consumption is more likely to be driven by positive reinforcement (e.g., pleasant feelings and social enhancement effects) whereas alcohol problems are more strongly associated with negative reinforcement (e.g., motivation to cope with stress and relief from negative affect; Cho et al., 2019). Because racial discrimination increases individuals’ psychological stress and negative affect, we expected that the association between racial discrimination and alcohol problems may be stronger than the association between racial discrimination and alcohol consumption. Indeed, a recent review of prior research suggest a stronger effect of racial discrimination for alcohol problems than for alcohol consumption (Gilbert & Zemore, 2016).

We hypothesized that experience of both blatant racist events and subtle racial microaggressions would be associated with higher levels of alcohol consumption and more alcohol problems. Parental racial socialization would be associated with young adult alcohol use outcomes. Specifically, we hypothesized that parental cultural socialization would be associated with lower alcohol consumption and fewer alcohol problems, whereas parental promotion of mistrust would be associated with more alcohol consumption and problems. We expected to observe similar patterns of associations for friend racial socialization. We further hypothesized that the associations between racial discrimination and alcohol use outcomes would be moderated by parental and friend racial socialization, such that the associations between racial discrimination and alcohol use outcomes would be weaker when cultural socialization is high and stronger when promotion of mistrust is high. Given mixed findings regarding the role of preparation of bias, we did not have specific hypothesis regarding its main and moderating effects.

Method

Sample and Procedures

Data for the present study came from the Cultural Experiences and Alcohol Use (CEAU) Study aimed at understanding the influence of genetic and cultural factors on alcohol use and related outcomes in African American young adults. The CEAU study is a spin-off study of the Spit for Science Study (S4S), an ongoing longitudinal study of how genetic and environmental factors impact substance use and behavioral health outcomes across the college years and beyond (Dick et al., 2014). The S4S invites incoming students aged 18 or older in a large public urban university in the mid-Atlantic region to participate in an online survey at the beginning of the fall semester of their freshman year and provide a saliva sample for genotyping. Participants subsequently complete a follow-up online survey each spring while attending college. Data collection for the S4S began in the fall of 2011, and five cohorts (cohorts 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, and 2017) of incoming freshman students have been enrolled in the study (n = 12,025), with 67% participation rate.

The CEAU study invited a subset of participants from the S4S who self-identified as Black/African American and provided a saliva sample to complete an additional online survey that included comprehensive measures on cultural and race-related experiences and alcohol use behaviors. In September 2017, invitation emails were sent to 1,989 eligible participants, of which 519 (26%) expressed interest in participating and were followed up with emails including a link to complete the online survey. A total of 394 (73%) participants consented and completed the survey by December 2017. Because participants in the CEAU study are also part of the S4S, researchers are able to link the data provided in both studies for the current analysis. All surveys in the S4S and the CEAU spin-off study were administered using the REDCap software (Harris et al., 2009). Informed consent was obtained electronically from participants and study procedures were approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board.

Of the 394 participants who completed the survey for the CEAU study, 383 self- identified as Black/African American, 10 self-identified as of other race/ethnicity, and one chose not to report race/ethnicity. In the present study, we included only those who self-identified as Black/African American. Participants ranged in age from 18 to 31 years (M = 20.65, SD = 2.28), with 81% of the sample self-identified as female.

Measures

Sample items for the measures are presented in the Appendix 1. Internal consistency and reliability (i.e., Cronbach’s alpha) for the measures are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | -- | ||||||||||||

| 2. Gender | −.03 | -- | |||||||||||

| 3. Parent education | −.04 | .05 | -- | ||||||||||

| 4. Racist events | .00 | −.03 | −.01 | -- | |||||||||

| 5. Microaggression | −.09 | −.01 | .04 | .61** | -- | ||||||||

| 6. Par cultural soc | −.05 | .06 | .16** | .23** | .28** | -- | |||||||

| 7. Par prep for bias | −.12* | .00 | .11* | .27** | .37** | .59** | -- | ||||||

| 8. Par prom of mistrust | .02 | .11* | .02 | .18** | .20** | .23** | .21** | -- | |||||

| 9. Friend cultural soc | .06 | .03 | .03 | .17** | .24** | .44** | .34** | .14** | -- | ||||

| 10. Friend prep for bias | .01 | .05 | .00 | .19** | .29** | .26** | .31** | .09 | .71** | -- | |||

| 11. Friend prom of mistrust | −.02 | .08 | −.01 | .15** | .29** | .15** | .15** | .34** | .40** | .43** | -- | ||

| 12. Alcohol consumption | .27** | .06 | .05 | .07 | .10 | −.04 | −.00 | .00 | −.04 | −.02 | .01 | -- | |

| 13. Alcohol problems | .23** | .07 | .01 | .13* | .17** | −.02 | −.03 | .09 | .01 | .01 | .12* | .89** | -- |

| M | 20.65 | .19a | 7.45 | 33.89 | 1.20 | 2.18 | 2.68 | 1.02 | 1.47 | 1.62 | .82 | 3.15 | 1.26 |

| SD | 2.28 | -- | 1.60 | 15.44 | 1.06 | .96 | .98 | 1.09 | 1.05 | 1.15 | 1.02 | 2.03 | .84 |

| Range | 18–31 | -- | 2–9 | 17–99 | 0–4.69 | 0–4 | 0–4 | 0–4 | 0–4 | 0–4 | 0–4 | 0–7.75 | 0–3.33 |

| Cronbach’s alpha | -- | -- | -- | .92 | .97 | .85 | .87 | .90 | .89 | .90 | .94 | -- | .85 |

| N | 383 | 381 | 380 | 383 | 378 | 382 | 381 | 380 | 376 | 376 | 374 | 380 | 381 |

Note. Par = parent, soc = socialization, pre for bias = preparation for bias, prom of mistrust = promotion of mistrust.

p < .05

p < .01

Alcohol consumption and alcohol problems were log transformed.

Gender is coded 1 = male, 0 = female; percentage of males is presented.

Racist events.

Participants reported on the frequency with which they had experienced 17 different events that can be considered a blatant form of racial discrimination in the past year via the Schedule of Racist Events (Landrine & Klonoff, 1996). Response options ranged from 0 (this has never happened to me) to 5 (this has happened almost all the time). Sum scores were calculated across items.

Racial microaggressions.

Participants completed the 45-item Racial and Ethnic Microaggressions Scale (Nadal, 2011), which assessed the extent to which individuals experienced subtle statements and behaviors that unconsciously communicated denigrating messages in the past six months. The scale consists of six subscales: Assumptions of Inferiority (8 items), Second-Class Citizen and Assumption of Criminality (7 items), Microinvalidations (9 items), Exoticization/Assumptions of Similarity (9 items), Environmental Microaggressions (7 items), and Workplace and School Microaggressions (5 items). Response options for each item ranged from 0 (I did not experience this event) to 5 (I experienced this event 5 or more times in the past six months). Items of each subscale were averaged to create a mean score. Preliminary analyses indicated that the environmental microaggressions subscale was negatively correlated with other subscales (r ranged from −.25 to −.33), whereas the other subscales were positively correlated with each other (r ranged from .62 to .80). Thus, total scores for racial microaggression were calculated by averaging scores across all the subscales except for the environmental microaggressions subscale.

Parental and friend racial socialization.

Participants reported on the frequency with which their parents engaged in cultural socialization (4 items), preparation for bias (4 items), and promotion of mistrust (2 items) while growing up via a 10-item measure of parental racial socialization developed for use with African American families (Hughes & Johnson, 2001). This measure has been adapted to measure perceived parental racial socialization among African American college students (Dunbar, Perry, Cavanaugh, & Leerkes, 2015). Similar to Dunbar et al.’s approach, we modified the questions to reflect the perspective of the adult child rather than a parent-report. We also adapted the measure to assess racial socialization by friends. Participants were asked to indicate on a scale from 0 (never) to 4 (always) how often their parents and friends (separately) engaged in specific behaviors with them when growing up. Items of each subscale for parental and friend racial socialization were averaged to create separate mean scores.

Alcohol consumption.

Participants completed the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Babor, De La Fuente, Saunders, & Grant, 1992), a 10-item self-report measure developed by the World Health Organization to screen individuals with alcohol use problems. Alcohol consumption was operationalized as grams of ethanol consumed per month, calculated based on participant’s responses to two items from the AUDIT assessing their frequency and quantity of alcohol use, following the approach described by Salvatore and colleagues (2016). Higher scores indicated higher alcohol consumption.

Alcohol problems.

Alcohol problems were measured by summing across all of the 10 items from AUDIT (Babor et al., 1992), including items related to alcohol consumption and related problems. Responses ranged from 0 (never) to 4 (daily or almost daily); higher scores indicated more alcohol problems. Preliminary analysis indicated that both alcohol consumption and alcohol problems were positively skewed (skewness = 4.22 and 2.16, respectively). Thus, we log-transformed these variables to correct for non-normality. The log-transformed alcohol consumption and alcohol problems variables were no longer skewed (skewness = −.12 and .06, respectively).

Covariates.

We considered gender (1 = male, 0 = female), age, and parental education as control variables, given prior evidence that being male and older is associated with higher levels of racial socialization and more alcohol consumption and that higher parental education is associated with more racial socialization and lower offspring alcohol consumption (Grant et al., 2015; Hughes, 2006; Schulte, Ramo, & Brown, 2009). Data on parental education were drawn from the freshmen fall survey data from S4S. Participants were asked to indicate the highest level of education attained by their father/mother figure. Valid responses ranged from 0 (she/he never went to school) to 9 (professional training beyond a four-year college or university). The higher score between maternal and paternal education was used to indicate parental education. For participants who were missing data for one parent (n = 6 for maternal education, n = 47 for paternal education), information regarding education level of the other parent was used. Maternal education and paternal education were moderately correlated (r = .43).

Analysis

We conducted preliminary analyses to examine descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations between study variables using SPSS version 24.0. We then conducted hierarchical linear regression analyses in Mplus version 7.31 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012) to examine the relations between racial discrimination, racial socialization, and alcohol use outcomes (i.e., alcohol consumption and alcohol problems). Specifically, we started with a regression model examining main effects of blatant and subtle forms of racial discrimination (i.e., racist events or racial microaggressions), controlling for gender, age, and parental education (Step 1). Next, we added parental or friend racial socialization (i.e., cultural socialization, preparation for bias, and promotion of mistrust) as independent variables to the regression model (Step 2) to examine main effects of racial socialization practices, above and beyond the effects of racial discrimination. Finally, to examine the moderating effects of racial socialization on the associations between racial discrimination and alcohol use outcomes, product terms were calculated between mean-centered racial discrimination and racial socialization variables and added to the regression model (Step 3). Significant interaction effects were further probed following the approach suggested by Aiken and West (1991). We conducted these analyses separately for racist events and racial microaggressions, separately for parental and friend racial socialization, and separately for alcohol consumption and alcohol problems, in order to examine whether patterns of relationships were similar or different for experience of blatant versus subtle forms of discrimination, for parental versus friend racial socialization, and across different alcohol use outcomes. Missing data (less than 5% for all variables) were accounted for using the full information maximum likelihood estimation method.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations between study variables. Experiences of more racist events and racial microaggressions were correlated with more alcohol problems (r = .13 and .17, respectively), but not significantly correlated with alcohol consumption (r = .07 and .10, respectively). Racist events and racial microaggressions were positively correlated (r = .61), suggesting that they are related but distinct constructs. Experiences of more racist events and racial microaggressions were correlated with higher parental and friend racial socialization (r ranged from .15 to .37). Parental and friend racial socialization were generally not significantly correlated with alcohol consumption and alcohol problems, except that friend promotion of mistrust was correlated with more alcohol problems (r = .12).

We examined potential differences between participants of the present study and eligible participants from the S4S who did not enroll in the present spin-off study. Compared to those who did not enroll in the present study, individuals who participated in the present study were more likely to be female (χ2 = 15.49, df = 1, p < .001). There were no differences in age (t = 1.69, p = .09), parental education (t = 1.45, p = .15), and alcohol consumption (t = −.95, p = .34) at the baseline S4S assessment during their freshmen year between participants and non-participants of the present study.

Main Effects of Racial Discrimination on Alcohol Use Outcomes

Results from regression analyses predicting alcohol use outcomes from experiences of racist events and microaggressions are presented in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. Consistent with our hypothesis, more frequent experience of racist events was associated with more alcohol problems. However, experience of racist events was not associated with alcohol consumption. Experience of racial microaggressions was associated with higher alcohol consumption and more alcohol problems.

Table 2.

Predicting Alcohol Consumption and Problems From Racist Events and Parental and Friend Racial Socialization

| Alcohol Consumption | Alcohol Problems | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parental Socialization | Friend Socialization | Parent Socialization | Friend Socialization | |||||||||

| B | SE | β | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | |

| Step 1 | ||||||||||||

| Gender | .34 | .26 | .07 | .34 | .26 | .07 | .19 | .11 | .09 | .19 | .11 | .09 |

| Age | .25 | .04 | .28** | .25 | .04 | .28** | .09 | .02 | .23** | .09 | .02 | .23** |

| Parent Education | .08 | .06 | .06 | .08 | .06 | .06 | .01 | .03 | .01 | .01 | .03 | .01 |

| Racist Events | .01 | .01 | .08 | .01 | .01 | .08 | .01 | .00 | .14** | .01 | .00 | .14** |

| Step 2 | ||||||||||||

| Cultural Socialization | −.19 | .13 | −.09 | −.17 | .14 | −.09 | −.04 | .05 | −.05 | −.04 | .06 | −.04 |

| Preparation for Bias | .12 | .13 | .06 | .03 | .13 | .02 | −.02 | .05 | −.03 | −.04 | .05 | −.05 |

| Promotion of Mistrust | −.04 | .10 | −.02 | .04 | .11 | .02 | .05 | .04 | .07 | .11 | .05 | .14* |

| Step 3 | ||||||||||||

| Racist events x CulSoc | −.00 | .01 | −.03 | −.02 | .01 | −.21* | −.00 | .01 | −.04 | −.01 | .01 | −.24* |

| Racist events x PrepBias | −.00 | .01 | −.02 | .02 | .01 | .18 | −.00 | .00 | −.02 | .01 | .00 | .19 |

| Racist events x ProMistrust | −.01 | .01 | −.07 | .01 | .01 | .06 | −.00 | .00 | −.06 | .01 | .00 | .11 |

Note. CulSoc = cultural socialization; PrepBias = preparation for bias; ProMistrust = promotion of mistrust.

p < .05

p < .01

Statistically significant main effects and interaction effects of racist events and racial socialization are bolded.

Table 3.

Predicting Alcohol Consumption and Problems From Racial Microaggression and Parental and Friend Racial Socialization

| Alcohol Consumption | Alcohol Problems | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parental Socialization | Friend Socialization | Parent Socialization | Friend Socialization | |||||||||

| B | SE | β | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | |

| Step 1 | ||||||||||||

| Gender | .34 | .26 | .07 | .34 | .26 | .07 | .18 | .11 | .08 | .18 | .11 | .08 |

| Age | .26 | .04 | .29** | .26 | .04 | .29** | .09 | .02 | .25** | .09 | .02 | .25** |

| Parent Education | .07 | .06 | .06 | .07 | .06 | .06 | .00 | .03 | .01 | .00 | .03 | .01 |

| Racial Microaggression | .24 | .10 | .15* | .24 | .10 | .15* | .16 | .04 | .19** | .16 | .04 | .19** |

| Step 2 | ||||||||||||

| Cultural Socialization | −.20 | .13 | −.09 | −.18 | .14 | −.09 | −.05 | .05 | −.05 | −.04 | .06 | −.05 |

| Preparation for Bias | .07 | .13 | .03 | −.00 | .13 | −.00 | −.05 | .05 | −.06 | −.05 | .05 | −.07 |

| Promotion of Mistrust | .06 | .10 | −.03 | −.01 | .11 | −.01 | .05 | .04 | .06 | .09 | .05 | .11 |

| Step 3 | ||||||||||||

| Microaggression x CulSoc | −.02 | .13 | −.01 | −.15 | .14 | −.09 | −.01 | .05 | −.01 | −.07 | .06 | −.10 |

| Microaggression x PrepBias | −.10 | .13 | −.05 | .16 | .13 | .11 | −.08 | .06 | −.09 | .07 | .05 | .11 |

| Microaggression x ProMistrust | −.06 | .09 | −.03 | .16 | .10 | .10 | −.01 | .04 | −.02 | .10 | .04 | .14* |

Note. CulSoc = cultural socialization; PrepBias = preparation for bias; ProMistrust = promotion of mistrust.

p < .05

p < .01

Statistically significant main effects and interaction effects of racist events and racial socialization are bolded.

Main and Moderating Effects of Parental and Friend Racial Socialization

As shown in Table 2 and Table 3, contrary to our hypotheses, parental racial socialization, including cultural socialization, preparation for bias, and promotion of mistrust, was not associated with alcohol consumption and alcohol problems, nor did these parental racial socialization practices moderate the associations between racist events and racial microaggressions and alcohol use outcomes. However, some significant effects of friend racial socialization were observed.

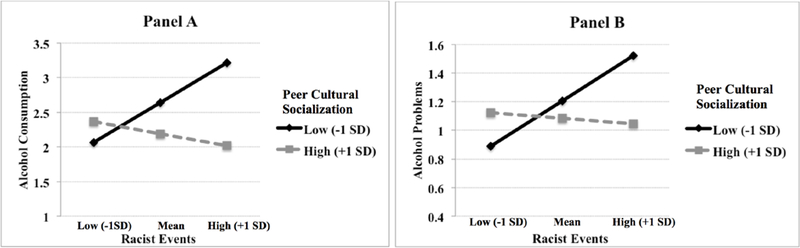

Specifically, although friend cultural socialization was not significantly associated with alcohol use outcomes, there were significant interaction effects between friend cultural socialization and racist events in relation to alcohol consumption and alcohol problems. Simple slope analyses indicated that experience of racist events was associated with higher alcohol consumption (B = .04, SE = .02, β = .29, 95% CI [.10, .47], p = .01) and more alcohol problems (B = .02, SE = .01, β = .37, 95% CI [.18, .55], p = .001) when friend cultural socialization was low (−1 SD), but was not associated with alcohol consumption (B = −.01, SE = .01, β = −.08, 95% CI [−.25, .08], p = .40) and alcohol problems (B = −.00, SE = .01, β = −.04, 95% CI [−.21, .12], p = .66) when friend cultural socialization was high (+1 SD). This pattern of interaction effects is illustrated in Figure 1. There was no significant interaction effect between friend cultural socialization and racial microaggressions on alcohol use outcomes.

Figure 1. Moderating Effects of Friend Cultural Socialization on the Associations between Racist Events and Alcohol Use Outcomes.

Note. Y-axis represents predicted values of log transformed alcohol consumption (Panel A) and alcohol problems (Panel B). Predicted values of alcohol use outcomes as a function of racist events and friend cultural socialization at prototypical values (+/− 1 SD) are shown.

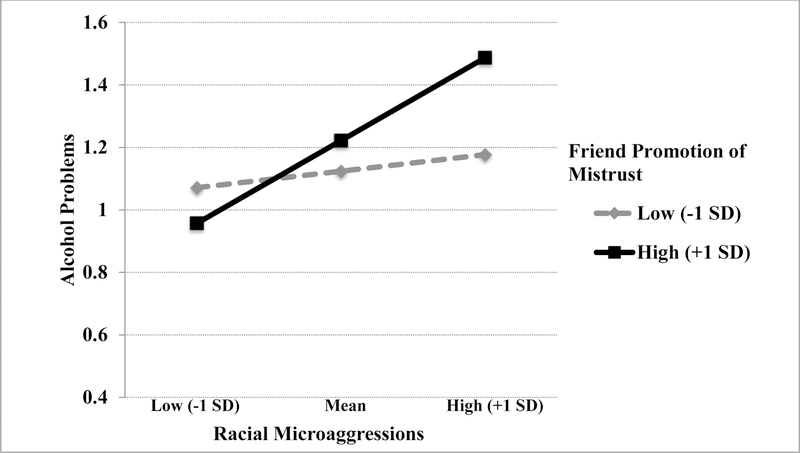

Friend promotion of mistrust was associated with more alcohol problems but was not associated with alcohol consumption. In addition, friend promotion of mistrust interacted with racial microaggressions in predicting alcohol problems but not alcohol consumption. Simple slope analyses indicated that experience of racial microaggressions was associated with more alcohol problems when friend promotion of mistrust was high (+1 SD, B = .25, SE = .06, β = .31, 95% CI [.20, .43], p < .001) but not when friend promotion of mistrust was low (−1 SD, B = .05, SE = .06, β = .06, 95% CI [−.06, .19], p = .41). This pattern of interaction effects is shown in Figure 2. There was no interaction effect between friend promotion of mistrust and racist events in relation to alcohol use outcomes.

Figure 2. Moderating Effects of Friend Promotion of Mistrust on the Association between Racial Microaggressions and Alcohol Problems.

Note. Y-axis represents predicted values of log transformed alcohol problems. Predicted values of alcohol problems as a function of racial microaggressions and promotion of mistrust by friends at prototypical values (+/− 1 SD) are shown.

Results indicated that friend preparation for bias was not associated with alcohol consumption and alcohol problems. We also found no evidence that friend preparation for bias moderated the relations between racist events and racial microaggressions and alcohol use outcomes.

Discussion

Using data from a sample of African American young adults, we examined the relations between blatant and subtle forms of racial discrimination (i.e., racist events and racial microaggressions) and alcohol use and problems, and the role of childhood/adolescence racial socialization by parents and friends in moderating these relations. Results indicated that, overall, experiences of racist events and racial microaggressions were associated with higher alcohol consumption and/or more alcohol problems. These associations were moderated by friend (but not parental) racial socialization, such that friend cultural socialization buffered the effect of racist events on alcohol consumption and problems, and peer promotion of mistrust exacerbated the effect of racial microaggressions on alcohol problems.

A large literature indicates that racial discrimination is a robust risk factor for negative psychosocial outcomes among African Americans (Benner et al., 2018; Harrell, 2000; Priest et al., 2013; Williams & Mohammed, 2009). Our results built on prior research to show that both blatant (i.e., racist events) and subtle (i.e., racial microaggressions) forms of racial discrimination are associated with higher alcohol consumption and/or problems. Notably, rates of racial discrimination were relatively low in our sample. Our findings highlight that racial discrimination has negative influences on alcohol use outcomes even when experienced infrequently. Consistent with prior research (Gilbert & Zemore, 2016), we found that experience of racist events was associated with more alcohol problems but not alcohol consumption. Experience of racist events could be a stressor that leads individuals to drink alcohol in a problematic pattern (e.g., drinking to cope), but may not be associated with alcohol consumption, which can occur in different settings with different motives (e.g., drinking to enhance social performance), and in and of itself is not necessarily problematic. Indeed, drinking to cope with stress or negative affect, which may be a consequence of the experience of racist events, is a well-documented internalizing pathway of risk to the development of alcohol problems (Anker et al., 2017), but not (or weakly) associated with alcohol consumption (Thomas, Merrill, von Hofe, & Magid, 2014). We note that racial microaggressions were reported on a more recent time frame (i.e., last six months) than racist events (i.e., last year), which may have contributed to the difference in the strength of associations between these factors and alcohol consumption.

Prior research linking racial discrimination and alcohol use outcomes has primarily focused on blatant forms of racial discrimination, such as experience of racist events (Gilbert & Zemore, 2016). Our findings contribute to the extant literature by showing that experiences of subtle forms of racial discrimination (i.e., microaggressions) were also associated with both higher alcohol consumption and more alcohol problems. The experience of microaggressions can be particularly harmful psychologically due to attribution ambiguity; that is, it is hard to tell whether the unfair treatment is due to racism or other factors such as their personality, skills, and abilities (Crocker & Major, 1989). This ambiguity may lead to heightened psychological stress, and consequently, more alcohol consumption and problems.

Prior research suggests that racial socialization plays an important role in the psychosocial adjustment among racial/ethnic minority children and adolescents (Hughes et al., 2006), and may buffer or exacerbate the effect of racial discrimination depending on the specific racial socialization practices (Burt et al., 2012; Neblett et al., 2010). The present study extended prior research to examine the role of racial socialization on alcohol use outcomes in young adulthood. Contrary to our hypothesis, racial socialization by parents in childhood/adolescence was not associated with alcohol consumption and alcohol problems, nor did it moderate the associations between racial discrimination and alcohol use outcomes. These findings are consistent with prior research that also found no significant effect of racial socialization on substance use outcomes among African American college students and adults (Bowman Heads et al., 2018; Thompson et al., 2016). Thus, despite the documented important role of parental racial socialization for adolescents’ psychosocial functioning, our findings suggest that it may have limited influence on young adult offspring’s alcohol use outcomes.

Consistent with our hypothesis, our findings indicated that childhood/adolescence racial socialization by friends was associated with alcohol use outcomes among African American young adults, and the associations varied depending on the specific dimensions of racial socialization practices and messages. Specifically, friend cultural socialization buffered the adverse effect of racist events on alcohol consumption and alcohol problems such that experience of racist events was associated with higher levels of alcohol consumption and more alcohol problems when peer cultural socialization was low but not when peer cultural socialization was high. This is largely consistent with prior evidence regarding the protective effect of cultural socialization on buffering negative influences of racial discrimination on psychosocial outcomes (Burt et al., 2012; Harris-Britt et al, 2007). The current findings highlight the importance of friends who serve a protective role against experiences of racist events. It is possible that receiving cultural socialization from friends throughout childhood/adolescence promotes individuals to build a sense of pride in being a member of their racial/ethnic group, which could protect individuals from experiencing high levels of stress and negative affect and developing alcohol problems in the face of racial discrimination.

Also consistent with our hypothesis, promotion of mistrust by friends was associated with more alcohol problems and exacerbated the negative influences of racial microaggressions on alcohol problems. This is consistent with prior evidence that promotion of mistrust serves as a risk factor for poor psychosocial outcomes including higher substance use (Grindal & Nieri, 2016), and that messages about prejudice communicated by peers play a unique role in psychosocial adjustment of racial-ethnic minority young adults (Nelson et al., 2018). A sense of mistrust of individuals from other racial/ethnic groups may make individuals more prone to perceive subtle forms of discrimination and generate negative affect which in turn are associated with higher risk for alcohol use and problems.

Finally, we found no evidence linking friend preparation for bias and alcohol use outcomes. Prior findings regarding the role of preparation for bias have been mixed, and more research is needed to clarify the effects of this specific aspect of racial socialization on alcohol use outcomes. Our findings highlight the importance of recognizing racial socialization as a multidimensional construct (Hughes et al., 2006) and understanding the differential role of specific racial socialization practices on individuals’ psychosocial outcomes.

Taken together, our findings suggest that childhood/adolescence racial socialization by friends, but not parents, is associated with young adult alcohol use outcomes. Childhood/adolescence racial socialization practices may shape individuals’ response to race-related stressors, which can be carried forward to influence individuals’ adjustment later in life, particularly in the face of racial discrimination. Consistent with prior research, our findings suggest that peers, including friends, serve as an important developmental context that play a role in alcohol use outcomes during young adulthood (Schulenberg & Maggs, 2002). Alternatively, it is possible that racial socialization messages from friends who may share experiences of being unfairly treated due to their race are more likely to be internalized and carried forward into young adulthood, compared to messages conveyed by parents. Longitudinal research is needed to replicate our findings and investigate the mechanisms underlying differential associations of parental and peer racial socialization across development.

The present study has several notable strengths, including the consideration of both blatant and subtle forms of racial discrimination, examination of the role of multiple dimensions of racial socialization by both parents and friends, and the focus on a sample of African American young adults, an understudied population in the racial socialization literature as most of prior research focused on adolescents. Despite these strengths, our findings need to be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, this is a cross-sectional study, limiting our ability to make inference about causality. For example, while racial microaggressions may lead individuals to consume alcohol, potentially as a way to cope with related stress and negative affect, it is also possible that African Americans who have more alcohol problems tend to perceive more racial microaggressions. Second, all of the measures were self-report and thus may subject to reporting bias. In particular, childhood/adolescence racial socialization were retrospective reports and may not accurately represent the actual racial socialization messages participants received growing up. In addition, the associations between childhood/adolescence racial socialization and alcohol use outcomes may reflect long-term effects of childhood/adolescence racial socialization or consistent interactions that occur over time because young adults may still have contact with their parents and childhood/adolescence friends and engage in racial socialization process with them. It would be important to measure racial socialization both in childhood/adolescence and young adulthood in future studies to disentangle long-term versus concurrent influences of racial socialization. Third, our sample was primarily female (> 80%) and the levels of alcohol consumption and problems were relatively low. Given that rates of alcohol consumption and problems (Grant et al., 2015), experience of racial discrimination (Williams & Mohammed, 2009), as well as socialization practices (Hughes et al., 2006) differ across gender, it is possible that the patterns of relations between them also differ across gender. We were not able to test this possibility due to the small sample size for males, and we acknowledge that our findings may be more representative for females and may not generalize to other high-risk samples. Finally, our sample included African American young adults who were college students or recent college graduates, and findings may not generalize to non-college-attending young adults and other racial/ethnic minority populations.

In conclusion, our findings indicate that racist events and racial microaggressions are risk factors associated with more alcohol consumption and problems. Racial socialization by friends (but not parents) while growing up plays a role in buffering or exacerbating the risks associated with experiences of racial discrimination, depending on the specific type of racial socialization practices and messages. These findings highlight the importance of considering different forms of racial discrimination, and emphasize the unique roles of racial socialization across different social contexts (i.e., parent and peers/friends) in relation to psychosocial outcomes among racial/ethnic minority individuals.

Acknowledgements:

Spit for Science: The VCU Student Survey has been supported by Virginia Commonwealth University, P20 AA107828, R37AA011408, K02AA018755, and P50 AA022537 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, and UL1RR031990 from the National Center for Research Resources and National Institutes of Health Roadmap for Medical Research.

Appendix 1. Sample Items for the Measures of Key Variables

| Variable | Sample Item |

|---|---|

| Racist Events | How many times in the past year have you been treated unfairly by teachers and professors because you are Black? |

|

Racial microaggressions | |

| Assumption of inferiority | Someone assumed that I would have a lower education because of my race. |

| Second-Class Citizen and Assumption of Criminality | Someone avoided walking near me on the street because of my race. |

| Microinvalidations | Someone told me that they do not see races. |

| Exoticization/Assumptions of Similarity | Someone assumed that I spoke a language other than English. |

| Workplace and School Microaggressions | An employer or co-worker was unfriendly or unwelcoming toward me because of my race. |

|

Parental racial socialization | |

| Parental cultural socialization | Growing up, how often did your parents talk to you about important people or events in your group’s history? |

| Parental preparation for bias | Growing up, how often did your parents tell you that you must be better to get the same rewards with others because of your race? |

| Parental promotion of mistrust | Growing up, how often did your parents do or say things to encourage you to keep distance from people of other races? |

|

Friend racial socialization | |

| Friend cultural socialization | Growing up, how often did your friends talk to you about important people or events in your group’s history? |

| Friend preparation for bias | Growing up, how often did your friends tell you that you must be better to get the same rewards with others because of your race? |

| Friend promotion of mistrust | Growing up, how often did your friends do or say things to encourage you to keep distance from people of other races? |

|

Alcohol Consumption | |

| Frequency of Alcohol use | How often do you have a drink containing alcohol? 0 (never), 1(monthly or less), 2 (2 to 4 times a month), 3 (2 to 3 times a week), 4 (4 or more times a week) |

| Quantity of alcohol use | How many drinks containing alcohol do you have on a typical day when you are drinking?” 0 (1 or 2), 1 (3 or 4), 2 (5 or 6), 3 (7, 8 or 9), 4 (10 or more) |

| Alcohol Problems | How often during the last year have you failed to do what was normally expected of you because of drinking? How often during the last year have you been unable to remember what happened the night before because of your drinking? |

References

- Aiken LS, & West SG (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Anker JJ, Forbes MK, Almquist ZW, Menk JS, Thuras P, Unruh AS, & Kushner MG (2017). A network approach to modeling comorbid internalizing and alcohol use disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 126, 325–339. doi: 10.1037/abn0000257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, De La Fuente J, Saunders J & Grant M (1992). AUDIT: The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for Use in Primary Health Care Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Benner AD, Wang Y, Shen Y, Boyle AE, Polk R, & Cheng Y (2018). Racial/ethnic discrimination and well-being during adolescence: A meta-analytic review. American Psychologist, 73, 855–883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berenz EC, Kevorkian S, Chowdhury N, Dick DM, Kendler KS, & Amstadter AB (2016). Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, anxiety sensitivity, and alcohol use motives in college students with a history of interpersonal trauma. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 30, 755–763. doi: 10.1037/adb0000193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blume AW, Lovato LV, Thyken BN, & Denny N (2012). The relationship of microaggressions with alcohol use and anxiety among ethnic minority college students in a historically White institution. Cultural Diversisty and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 18, 45–54. doi: 10.1037/a0025457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boynton MH, O’Hara RE, Covault J, Scott D, & Tennen H (2014). A mediational model of racial discrimination and alcohol-related problems among African American college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 75, 228–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt CH, Simons RL, & Gibbons FX (2012). Racial discrimination, ethnic-racial socialization, and crime: A micro-sociological model of risk and resilience. American Sociological Review, 77, 648–677. doi: 10.1177/0003122412448648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caughy MO, O’Campo PJ, Nettles SM, & Lohrfink KF (2006). Neighborhood matters: Racial socialization of African American children. Child Development, 77, 1220–1236. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00930.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chartier K, & Caetano R (2010). Ethnicity and health disparities in alcohol research. Alcohol Research and Health, 33, 152–160. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Frone MR, Russell M, & Mudar P (1995). Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 990–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper SM, & McLoyd VC (2011). Racial barrier socialization and the well-being of African American adolescents: The moderating role of mother-adolescent relationship quality. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21, 895–903. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2011.00749.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, & Major B (1989). Social stigma and self-esteem: The self-protective properties of stigma. Psychological Review, 96, 608–630. [Google Scholar]

- Dick DM, Nasim A, Edwards AC, Salvatore JE, Cho SB, Adkins A, ... & Kendler KS (2014). Spit for Science: Launching a longitudinal study of genetic and environmental influences on substance use and emotional health at a large US university. Frontiers in Genetics, 5(47), 1–12. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2014.00047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dotterer AM, McHale SM, & Crouter AC (2009). Sociocultural factors and school engagement among African American youth: The roles of racial discrimination, racial socialization and ethnic identity. Applied Developmental Science, 13, 51–73. doi: 10.1080/10888690902801442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar AS, Perry NB, Cavanaugh AM, & Leerkes EM (2015). African American parents’ racial and emotion socialization profiles and young adults’ emotional adaptation. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 21, 409–419. doi: 10.1037/a0037546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Coll C, Lamberty G, Jenkins R, McAdoo HP, Crnic K, Wasik BH, et al. (1996). An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development, 67, 1891–1914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert PA, & Zemore SE (2016). Discrimination and drinking: A systematic review of the evidence. Social Science and Medicine, 161, 178–194. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.06.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, Chou SP, Jung J, Zhang H, ... & Hasin DS (2015). Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry, 72, 757–766. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grindal M, & Nieri T (2016). The relationship between ethnic-racial socialization and adolescent substance use: An examination of social learning as a causal mechanism. Journal of Ethnicity and Substance Abuse, 15, 3–24. doi: 10.1080/15332640.2014.993785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell SP (2000). A multidimensional conceptualization of racism-related stress: Implications for the well-being of people of color. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 70, 42–57. doi: 10.1037/h0087722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, & Conde JG (2009). Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 42, 377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris-Britt A, Valrie CR, Kurtz-Costes B, & Rowley SJ (2007). Perceived racial discrimination and self-esteem in African American youth: Racial socialization as a protective factor. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 17, 669–682. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2007.00540.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman Heads AM, Glover AM, Castillo LG, Blozis S, & Kim SY (2018). Dimensions of ethnic identity as protective factors for substance use and sexual risk behaviors in African American college students. Journal of American College Health, 66, 178–186. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2017.1400975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingsworth DW, Cole AB, O’Keefe VM, Tucker RP, Story CR, & Wingate LR (2017). Experiencing racial microaggressions influences suicide ideation through perceived burdensomeness in African Americans. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 64, 104–111. doi: 10.1037/cou0000177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, & Chen L (1999). The nature of parents’ race-related communications to children: A developmental perspective. In Balter L & Tamis-Lemonda CS (Eds.), Child psychology: A handbook of contemporary issues (pp. 467–490). Philadelphia: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, & Johnson D (2001). Correlates in children’s experiences of parents’ racial socialization behaviors. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63, 981–995. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00981.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Rodriguez J, Smith EP, Johnson DJ, Stevenson HC, & Spicer P (2006). Parents’ ethnic-racial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study. Developmental Psychology, 42, 747–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Witherspoon D, Rivas-Drake D, & West-Bey N (2009). Received ethnic-racial socialization messages and youths’ academic and behavioral outcomes: Examining the mediating role of ethnic identity and self-esteem. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 15, 112–124. doi: 10.1037/a0015509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurd NM, Varner FA, Caldwell CH, & Zimmerman MA (2014). Does perceived racial discrimination predict changes in psychological distress and substance use over time? An examination among Black emerging adults. Developmental Psychology, 50, 1910–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Hatzenbuehler ML, & Hasin DS (2011). Stressful life experiences, alcohol consumption, and alcohol use disorders: The epidemiologic evidence for four main types of stressors. Psychopharmacology, 218, 1–17. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2236-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landrine H, & Klonoff EA (1996). The schedule of racist events: A measure of racial discrimination and a study of its negative physical and mental health consequences. Journal of Black Psychology, 22, 144–168. [Google Scholar]

- Latzman RD, Chan WY, & Shishido Y (2013). Impulsivity moderates the association between racial discrimination and alcohol problems. Addictive Behavior, 38, 2898–2904. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.08.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DB, Heinze JE, Neblett EW, Caldwell CH, & Zimmerman MA (2017). Trajectories of racial discrimination that predict problematic alcohol use Among African American emerging adults. Emerging Adulthood, doi: 10.1177/2167696817739022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby EE (1992). The role of parents in the socialization of children: An historical overview. Developmental Psychology, 28, 1006–1017. [Google Scholar]

- Major B, & Dover TL (2016). Attributions to discrimination: Antecedents and consequences. In Nelson TD (Ed.), Handbook of prejudice, stereotyping, and discrimination (pp. 213–239). New York, NY, US: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Major B, Quinton WJ, & McCoy SK (2002). Antecedents and consequences of attributions to discrimination: Theoretical and empiri-cal advances. In Zanna MP (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 34, pp. 251–300). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Myers HF (2009). Ethnicity-and socio-economic status-related stresses in context: An integrative review and conceptual model. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 32, 9–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulia N, Ye Y, Greenfield TK, & Zemore SE (2009). Disparities in alcohol-related problems among white, black, and Hispanic Americans. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 33, 654–662. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00880.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muraven M, & Baumeister RF (2000). Self-regulation and depletion of limited resources: Does self-control resemble a muscle? Psychological bulletin, 126, 247–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK and Muthén BO (1998–2012). Mplus User’s Guide Seventh Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén [Google Scholar]

- Nadal KL (2011). The Racial and Ethnic Microaggressions Scale (REMS): Construction, reliability, and validity. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58, 470–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadal KL, Griffin KE, Wong Y, Hamit S, & Rasmus M (2014). The impact of racial microaggressions on mental health: Counseling implications for clients of color. Journal of Counseling & Development, 92, 57–66. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6676.2014.00130.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neblett EW, Terzian M, & Harriott V (2010). From racial discrimination to substance use: The buffering effects of racial socialization. Child Development Perspectives, 4, 131–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson SC, Syed M, Tran AG, Hu AW, & Lee RM (2018). Pathways to ethnic-racial identity development and psychological adjustment: The differential associations of cultural socialization by parents and peers. Developmental psychology, 54, 2166–2180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oetting E, & Donnermeyer J (1998). Primary socialization theory: The etiology of drug use and deviance. I. Substance Use & Misuse, 33, 995–1026. doi: 10.3109/10826089809056252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe EA, & Smart Richman L (2009). Perceived discrimination and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 135, 531–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priest N, Paradies Y, Trenerry B, Truong M, Karlsen S, & Kelly Y (2013). A systematic review of studies examining the relationship between reported racism and health and wellbeing for children and young people. Social Science and Medicine, 95, 115–127. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.11.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pro G, Sahker E, & Marzell M (2017). Microaggressions and marijuana use among college students. Journal of Ethnicity and Substance Abuse, 1–13. doi: 10.1080/15332640.2017.1288191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds JE, & Gonzales-Backen MA (2017). Ethnic-racial socialization and the mental health of African Americans: A critical review. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 9, 182–200. doi: 10.1111/jftr.12192 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sacks JJ, Gonzales KR, Bouchery EE, Tomedi LE, & Brewer RD (2015). 2010 national and state costs of excessive alcohol consumption. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 49, e73–e79. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.05.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvatore JE, Thomas NS, Cho SB, Adkins A, Kendler KS, & Dick DM (2016). The role of romantic relationship status in pathways of risk for emerging adult alcohol use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 30, 335–344. doi: 10.1037/adb0000145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg JE, & Maggs JL (2002). A developmental perspective on alcohol use and heavy drinking during adolescence and the transition to young adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 14, 54–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte MT, Ramo D, & Brown SA (2009). Gender differences in factors influencing alcohol use and drinking progression among adolescents. Clinical Psychology Review, 29, 535–547. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R (2001) How does stress increase risk of drug abuse and relapse? Psychopharmacology, 158, 343–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small C (2010). Effects of mothers’ racial socialization and relationship quality on African American youth’s school engagement: A profile approach. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 16, 476–484. doi: 10.1037/a0020653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Bynum MA, Anderson RE, Davis BL, Franco MG, & English D (2016). Observed racial socialization and maternal positive emotions in African American mother-adolescent discussions about racial discrimination. Child Development, 87, 1926–1939. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer MB (2006). Phenomenology and Ecological Systems Theory: Development of Diverse Groups. In Lerner RM & Damon W (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Theoretical models of human development (pp. 829–893). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas SE, Merrill JE, von Hofe J, & Magid V (2014). Coping motives for drinking affect stress reactivity but not alcohol consumption in a clinical laboratory setting. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 75, 115–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson AB, Goodman MS, & Kwate NO (2016). Does learning about race prevent substance abuse? Racial discrimination, racial socialization and substance use among African Americans. Addictive Behavior, 61, 1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varner FA, Hou Y, Hodzic T, Hurd NM, Butler-Barnes ST, & Rowley SJ (2018). Racial discrimination experiences and African American youth adjustment: The role of parenting profiles based on racial socialization and involved-vigilant parenting. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 24, 173–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, & Benner AD (2016). Cultural socialization across contexts: Family-peer congruence and adolescent well-being. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45, 594–611. doi: 10.1007/s10964-016-0426-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Benner AD, & Kim SY (2015). The Cultural Socialization Scale: Assessing family and peer socialization toward heritage and mainstream cultures. Psychological Assessment, 27, 1452–1462. doi: 10.1037/pas0000136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, & Mohammed SA (2009). Discrimination and racial disparities in health: Evidence and needed research. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 32, 20. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapolski T, & Clifton R (2018). Cultural socialization and alcohol use: The mediating role of alcohol expectancies among racial/ethnic minority youth. Addictive Behaviors Reports doi: 10.1016/j.abrep.2018.100145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]