Abstract

The U.S. workforce is aging. There is a paucity of literature exploring aging nurses’ work ability. This study explored the work-related barriers and facilitators influencing work ability in older nurses. We conducted a qualitative descriptive study of aging nurses working in direct patient care (N=17). Participants completed phone or in-person semi-structured interviews. We used a content analysis approach to analyzing the data. The overarching theme influencing the work ability of aging nurses was intrinsically motivated. This was tied to the desire to remain connected with patients at bedside. We identified factors at the individual, unit-based work level, and organizational level associated with work ability. Individual factors that were protective included teamwork and feeling healthy and capable of doing their job. Unit-based level work factors included having a schedule that accommodated work-life balance and one’s chronotype promoted work ability. Organizational factors included management that valued worker’s voice supported work ability.

Keywords: occupational health, nursing workforce, qualitative methods, work ability

As of 2016, one-third of the total United States (U.S.) workforce was 50 years or older (Harrington & Heidkamp, 2013; Phillips & Miltner, 2015). Workers who are 65 years or older are projected to undergo a rapid growth, and will comprise nearly one in five workers (19%) in the U.S. workforce by 2050 (Harrington & Heidkamp, 2013). The aging worker phenomenon is taking place in the health care sector, particularly among registered nurses (“nurses”). By 2020, it is estimated that half of all working nurses in the U.S. will reach the traditional retirement age of 65 (Harrington & Heidkamp, 2013). This is partly explained by the dominance of nursing as a career choice for women during the peak of the baby boom (1955) (Keller & Burns, 2010; Sofer, 2018).

It is projected that by 2030, about one million of presently employed registered nurses will have retired (Sofer, 2018). While millennials (born between 1980 and 1994) have contributed to the growth of the nursing workforce, there are still concerns about regional nursing shortages, with some areas expecting to experience significant shortages (Sofer, 2018). Furthermore, it is unknown if the current and projected supply of nurses will be adequate to fully implement health system delivery re-design as part of the Affordable Care Act, in which nurses have a critical role (Keller & Burns, 2010). Finally, the number of Americans with chronic, complex health conditions is expected to grow, resulting in greater demand for health care services from nurses. The anticipated loss of “intellectual and human resources” in retiring nurses must be carefully weighed in the changing health care environment (Auerbach et al., 2013; Phillips & Miltner, 2015).

Occupational Health Considerations for Aging Nurses

The work environment for nurses in a direct-care position is full of safety and health hazards. Nursing care requires physical tasks with repeated bending, lifting, and twisting that can lead to musculoskeletal disorders (MSD). On average, nurses lift 1.8 tons during an 8-hour shift in the clinical setting, contributing to the estimated 35–80% lifetime prevalence of back injury (Nelson & Baptiste, 2004). Inserting intravenous catheters and administering intravenous medications increases nurses’ risk of needle sticks and sharps injuries, potentially exposing them to a host of blood borne pathogens (Clarke, 2007). Nurses also face on-the-job assault or verbal abuse from patients, families or co-workers, which can lead to psychological harm (Brewer, Kovner, Obeidat, & Budin, 2013; Budin, Brewer, Chao, & Kovner, 2013). Intensifying risks for occupational injuries within the acute-care setting include long hours, unpredictable shifts, and frequent overtime (Griffiths et al., 2014; Ma & Stimpfel, 2018; Stimpfel, Sloane, & Aiken, 2012; Stimpfel & Aiken, 2013; Stimpfel, Brewer, & Kovner, 2015; Trinkoff et al., 2011; Trinkoff, Le, Geiger-Brown, & Lipscomb, 2007; Trinkoff, Le, Geiger‐Brown, Lipscomb, & Lang, 2006). These working conditions can add to the likelihood of injury because rest time necessary for mental and physical recovery between shifts may be reduced (Trinkoff et al., 2006).

The U.S. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) recognizes health care workers as the leading occupational sector at risk for occupational injuries and illness (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, n.d.). Furthermore, it is well documented that prolonged recovery from work related, work-limiting injuries is more common as workers age (Delloiacono, 2016). While occupational risks associated with illness and injury among nurses are varied, occupational stress, patient handling, and shift work are noted as major contributors (Gomaa et al., 2015; Stimpfel et al., 2015; Thinkkhamrop & Laohasiriwong, 2015; Wallis, 2015). There is also evidence to suggest that 44% of all reported musculoskeletal injuries are attributed to overexertion and patient interaction (Gomaa et al., 2015; Wallis, 2015). Although occupational risks associated with nursing have long been established, which have led to ergonomic strategies for remediation (i.e. mechanical lifts, no-lift policies), problems persists (Bureau of Labor Statistics, n.d.; Budin et al., 2013; Stimpfel & Aiken, 2013; Trinkoff et al., 2006).

While the association between work demand and injury among nurses is well documented, these relationships have been inadequately explored among aging nurses. In addition, there is evidence to suggest that shift work, a feature of nurse’s work in many settings, has various deleterious health risks. For example, night shift work has been shown to correlate with poor sleep, weight gain, and metabolic syndrome (Hansen, Stayner, Hansen, & Andersen, 2016; Hruby et al., 2016; Zhang, Punnett, McEnany, & Gore, 2016). A recent study by Hansen et al. (2016) showed an increased risk for diabetes among nurses who worked evening and night shifts. Furthermore, co-morbidities including diabetes and occupational stress have been linked with worker disability (Ervasti et al., 2016). While these risks exist for all nurses, the risks are intensified and management is more complex for older workers (Phillips & Miltner, 2015). Therefore, efforts must be made to explore these complex occupational risks in an aging workforce to ensure that nurses can safely continue their jobs for as long as they wish to continue working. These efforts must include a deeper understanding of the occupational challenges faced by aging nurses, and mitigating processes that may ensure aging nurses’ health and wellness in the workplace.

Purpose

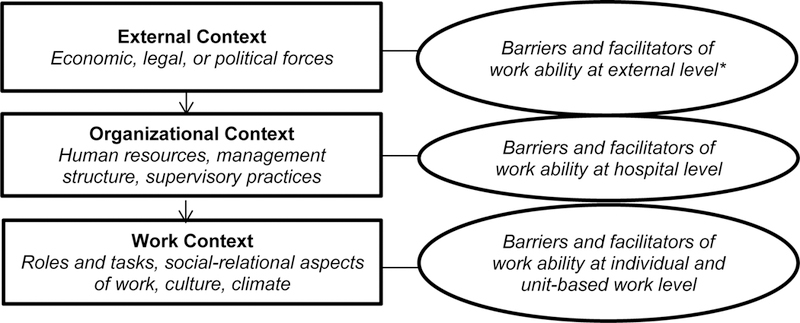

The purpose of this study was to explore work-related barriers and facilitators influencing work ability in aging nurses, guided by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) Organization of Work framework. The Organization of Work is defined as the work process (the way jobs are designed) and the organizational practices (management, production methods and human resource) policies that influence job design (NIOSH, 2008; Sauter et al., 2002). The framework’s three dimensions are: external, organizational, and work contexts. External context includes economic, legal or political forces. Organizational context includes human resources policies, management structures and supervisory practices. Work context refers to job characteristics such as worker roles, social-relational aspects of work, culture and climate, and worker tasks. There is a general consensus that new work organization trends are associated with increased stress, potentially hazardous work situations, reduced job stability, longer work hours and increased workloads. These factors are associated with work ability, which is conceptualized as the ability to work at present, in the near future and with respect to work demands, based on health and mental resources (Tuomi, Huuhtanen, Nykyri, & Ilmarinen, 2001; van den Berg, Elders, de Zwart, & Burdorf, 2009). For this project, we focused on understanding the organizational and work contexts as a first step in understanding the barriers and facilitators to work ability in aging nurses since these contexts are most proximal to the worker.

Methods

We conducted a qualitative descriptive study utilizing semi-structured interviews with eligible participants. Ethical approval to conduct the study was given by the Institutional Review Board of the authors’ institution. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant prior to participation.

Recruitment, sample, inclusion criteria

Study participants were recruited from the registered nurse (RN) workforce of a large urban academic medical center between August 2017 and March 2018. We used purposive sampling through targeted flier advertising within inpatient units, nursing committee presentations, and the personal recommendation of nurses participating in the study. Inclusion criteria included RNs between the ages of 50 and 89, English speakers, and working 20 or more hours in direct patient care on inpatient hospital units.

Procedures and data collection

Once participants were enrolled in the study, each participated in individual semi-structured interviews. Interviews were either in person in a private office space or over the phone as per the participant’s preference, lasted between 30 – 60 minutes, and were audio recorded for purposes of transcription. The interviewers were trained in qualitative research interview techniques prior to interviewing subjects. Interviews were semi-structured, with guided questions focused on barriers and facilitators influencing work ability within the work context including individual and unit-based work level factors, (e.g., “Please tell me about your experience with shift work”) and organizational context (hospital level) (e.g., “How does your organization and policies affect your ability to do your job?” ) domains of the Organization of Work. Since external context was not the focus of this study, we did not explicitly ask about economic, political or legal factors as barriers or facilitators. The interview guide questions were informed by our prior studies, which also focused on older workers (Dickson, 2013; Dickson, Howe, Deal, & McCarthy, 2012).

We also conducted a literature review to both gain a comprehensive understanding of the problem and to aid in the development of a relevant subject interview guide. The search utilized the CINAHL, PubMed, and Joanna Briggs Evidence Based Practice databases of peer reviewed research. The semi-structured interview guide included open ended questions (e.g., “Where do you see yourself at this organization, or in the nursing profession, in 5, 10 years?”) with follow up probes to elicit independent descriptions of the factors that influence work ability. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim; and accuracy was confirmed by referring to the interview recordings in cases when the transcript was unclear or the wording did not make sense. Data saturation (Creswell, 2007), i.e., no new information adding to the understanding of the study, was reached after 17 interviews (N=17).

Data analysis

We analyzed the qualitative data using a content analysis approach. Each interview was read line-by-line and coded using Atlas.ti version 8.0, a qualitative analysis software tool. Codes and categories were established a priori following the Organization of Work framework and if new concepts were noted during the line-by-line analysis, new codes were created. To ensure the rigor of the data analysis, the first several interviews were independently coded by E.L. and M.A. and achieved adequate intercoder reliability (Krippendorf’s c-alpha=.799). The remaining data analysis and coding were performed by E.L., an expert in coding textual data. Coding clusters were organized into categories, which were then further summarized into themes. We performed coding summarization within-cases, then across cases, and subsequently cross-classified them to yield a rich textual descriptive analysis (Table 2).

Table 2.

Themes

| Factors Influencing Work Ability |

Themes | Exemplar Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Theme | Work ability for older nurses is intrinsically motivated | |

| Individual | Age is only a number…until | “I feel like it’s the same. I’m in very good shape so I don’t feel—I run a lot. I take care of myself, so my energy level I don’t feel is limited by me getting older.” “I can’t say they facilitate it because I just had my third knee replacement, so it’s either you can come back to work in full capacity, or you don’t come back to this job. I don’t think it’s such a great idea because I think you have to – they keep saying the face of healthcare is changing, and the healthcare providers are aging, so I feel like they have to be accommodated. When I came back from my third knee replacement, if my surgeon said, “Listen, let her do phone calls for three weeks to let her ease back into the job,” they’d say, “Well, if she can’t come back in a full capacity, then she doesn’t come back.” It’s a little disconcerting.” “I don’t foresee any issues with me going someplace else unless some extraordinary circumstances that I don’t even like to entertain.” |

| Joy in patient care | “I think I’ll always love nursing, maybe not work as much [laughter]…but at the moment, I truly do love my—doing this, and yeah, I can see myself ten years doing it.” “I think I just—I work because I still enjoy it.” “I mean I’ve always loved nursing. I feel blessed that this is my career. I mean it’s tough sometimes, but at least I go home at the end of the day and you know you made a difference in someone’s life. You helped them through some difficult time. Cuz even though they’re coming in for testing it’s usually because there’s something they’re concerned about, or they’re worried about something. The tests sometimes can be scary. They’re afraid of the result et cetera, so nursing in general though I just think you go home, and at least you feel like you participated in trying to help someone. […] I see other people come home from their—there’s just no meaning in their work. There’s no meaning, and we have that. I feel nurses are so lucky we have that. I feel lucky that I’ve stayed at [this institution] all these years because I do think and they want us to do the best for the patients. That is nice to feel like you have that behind you also, so you feel good at least you have—I mean we have equipment, we have staff. A lot of hospitals don’t even have that, so it’s hard enough to take care of patients and let alone you’re missing things that should make everything simpler. “ |

|

| Unit | Don’t take my shift away | “Um-hum and then we went to 12 hours and I did days and nights. One of the reasons that I went to [another unit] was cause I didn’t have to, I really did not tolerate the night shift well at all and I wanted a job without the night shift.“ “I’ve been on permanent nights for more than 20 years. I’m lucky in the sense that I’m able to take a nap. Some people cannot sleep at all during the day. It doesn’t matter whether they’re drilling outside, there’s too much sun, that doesn’t matter, that doesn’t matter to me. I have no problem. Very rarely have I had issues with insomnia.” “For me personally, on 12 hour shift, I find it hard to work three days in a row. And so I ask my manager if I could work two and then be off at least one. It works out. She’s been accommodating to that. That’s a personal preference though. It’s not just totally age. For me, it’s also commuting. I travel and it takes me almost two hours to come each way. So when I add that to 12 hours, I’m just about getting home. By the third day, I’m tired.” |

| Camaraderie & Teamwork | “The nurses who have been there for a while, we’re all sometimes overwhelmed or need a little assistance, and they [younger nurses] are good with lending help without being critical. They’re very patient about that and it’s kind of a balance, because then we lend them help with some of the skills and nursing assessment and analysis and critical thinking. So I think it’s a good work flow.” “For me, it’s being in the institution for this long, I have attending’s that were residents under me, so I’ve taught them. We’ve developed collegial friendships and professional working environment that you know what they’re thinking before they even ask, which is nice. There’s definitely, there’s the plus of actually working in an institution for a while is that, you do work with people that you know.” “Honestly, I work with an incredible group of people. I’m the oldest one on the floor and most of the people I work with are in their 20s. Early 20s. A lot of the young, vibrant, intelligent young ladies. They are hard workers and they’re eager to help. They just all pitch in. We work really well together. I think I’m very lucky. I don’t know if it’s like that everywhere, but they just work together. If they see that I’m falling behind or exhausted, they’re like, “What do you need me to do?” and they’ll help out.” |

|

| Organization | Where is my voice? | “We asked our nurse manager and we actually picked our chairs and they’re very nice. I like our chairs.” “I mean, no. I really feel like they offer you every opportunity. You have to know who to ask and when to ask and get—they’re not gonna come to you. You have to go to them. “I don’t know this. I need help with that,” and you get it.” |

Results

Participants’ age ranged from 51 to 69 years old with mean age of 58.6 years (SD 5.4). All were female and most were white. Nearly half (47.1%) of participants reported a bachelor’s degree in nursing as the highest degree achieved, while an additional 41% reported holding a master’s degree in nursing. The majority of nurses worked full time (82.4%) and on the day shift (88.2%). Practice settings varied, from inpatient medicine floors to pediatrics, cardiology, and dialysis. The average work tenure of the participant cohort was 33.5 years (SD 4.5). For a detailed demographic and work characteristic summary, refer to Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and Work Characteristics of Participants

| Characteristic | M (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 58.6 (5.4) | |

| Years of Experience as RN | 33.5 (4.5) | |

| N (%) | ||

| Sex | ||

| Female | 17 (100) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White | 15 (88) | |

| Asian | 2 (12) | |

| Work Status | ||

| Full time | 14 (82) | |

| Part time | 3 (18) | |

| Shift Type | ||

| Day shift | 15 (88.2) | |

| Night shift | 2 (11.8) | |

| Highest Nursing Degree | ||

| BSN | 8 (47.1) | |

| MSN | 7 (41.2) | |

| DNP | 1 (5.9) | |

| Not reported | 1 (5.9) | |

| Current role | ||

| Charge nurse | 1 (5.9) | |

| Pediatric resuscitation coordinator | 1 (5.9) | |

| Perioperative nurse | 1 (5.9) | |

| Senior nurse clinician | 11 (64.7) | |

| Other | 3(17.6) | |

| Unit type | ||

| Cardiac Unit/Recovery Room | 8 (47.1) | |

| Dialysis | 4 (23.5) | |

| Medical/surgical | 2 (11.8) | |

| Mother/Baby Unit/Pediatrics | 2 (11.8) | |

| Acute care rehabilitation | 1 (5.9) | |

Note. BSN= bachelor of science in nursing, MSN= master of science in nursing, DNP= doctor of nursing practice.

N=17

Individual Level

Our findings’ overarching theme among aging nurses was continuing to work was intrinsically motivated. Among the domains in the Organization of Work, discussion of work-level factors and specifically individual-level factors affecting their work ability elicited the most robust responses. The joy of direct patient care – the patient-nurse relationship and the resulting human connection – emerged as a strong individual theme in facilitating work ability. Moreover, it was the relationships and connections to patients and families that was a strong reason for wanting to stay in direct care versus administration or an advanced practice role, even though several nurses held master’s degrees. One participant explained:

I actually love being a bedside nurse. I really enjoy that whole thing. That whole relationship with my patient. I like being there at night, especially, with hematology and oncology, because I find that a lot of the patients put up a good front during the day. Their family is there; the doctors are there. They’re brave and they’re going through everything. Then, night hits and they’re all alone and that’s when they need somebody. I like to fit into that role and help them relax and come to terms with whatever’s going on.

Feeling that “age is just a number” was also an enabling factor, as many nurses felt they were in good shape and did not consider themselves limited in any way due to their age. One participant said this about age, “It’s nothing but number. It’s true. It is true. You can have a very—you can have a 55-year-old who feels like they’re 65, and you have a 55-year-old who feels like 35.” On the other hand, nurses who had experienced temporary health setbacks e.g., knee replacement surgery, listed their health as a potential barrier to working in the future or as long into the future as they wanted. Most participants described a desire to continue working for the next 5 years or longer as long as they remained healthy. Because the majority of participants did not have dependents living at home at the present, family obligations were not universally discussed as a facilitator or barrier to work ability.

Unit-based Work Level

Working a preferred shift and schedule was identified as a major facilitator for continuing work as a unit-based work factor. Most nurses worked their preferred shift and schedule, which was not only a motivating factor in choosing their unit setting, but also positively affected their longevity within their respective units. Most correlated their chronotype, e.g. morningness or eveningness, with their preferred shift. One of the participants, who worked day shift, described herself:

“I’m an early person. Waking up at 4:15 doesn’t bother me, going to work 11:00 to 9:00– I live in <a distance>, coming home on the train that late, I couldn’t do it. I’m an early bird. I like to get up early, get in there, and get out.”

Another participant described her experience in the past working nights and then transitioning to days:

“I think I liked the idea of working just a day job. I had problems sleeping at night… I managed and I did it, but it became increasingly hard to get to sleep. I used to have anxiety that I would be at work and falling asleep… for my lifestyle <night shift> didn’t suit me… I didn’t feel like I was well rested.”

Several of the participants also described the importance of have flexibility in either the schedule they worked or the hours they worked as they reflected on their career path. One participant who spent over 25 years in the same specialty described the appeal of working a Monday-Friday schedule. “I saw this as a opportunity to get—to try something new in two different areas, and have the ability, actually, to work Monday to Friday because it was an eight-hour position then.”

Camaraderie and teamwork also emerged as a significant theme within unit-based work factors affecting work ability in older nurses. Nurses noted that in the units they work, colleagues shared similar interests and had similar demographic characteristics. Also, due to the longevity of the participants on their units, the comfort with interdisciplinary staff (e.g., attending physicians, residents, therapists) was largely a positive finding. One participant described her work with colleagues on the night shift. “I find that the night shift gets along great. We really work together. There’s not a lot of people around, so we really help each other. If there’s somebody that’s not doing well, they’ll all come in and help.”

Experienced older nurses reported pride in being senior staff members and being viewed as a knowledgeable mentor by newer nurses. Some participants reported a productive “give and take” environment, such as helping less experienced nurses with clinical and critical thinking tasks while receiving help from newer nurses with managing new technology and electronic health record (EHR) software. An example, “I’ve had the younger ones, now, teach me or make up smart phrases and do little things that make it a little bit faster for me”.

The increased use of technology and electronic medical record keeping were listed as perceived barriers to work ability although this varied among the participants. Some participants reported satisfactory technological dexterity while others reported being challenged by the EHR. While the technical aspects of using technology did not pose as a major barrier to continuing to work, the majority of participants described dissatisfaction with being taken away from direct patient engagement to use the computer for documentation. The subsequent decrease in the quality and quantity of the patient- nurse relationship, was cited as a barrier to finding “joy in work”.

Organizational Level

At the organizational level, the biggest factor affecting work ability was whether or not participants felt their voice was being “heard” by management and the organization as a whole. Nurses listed a supportive management and organizational structure as facilitators to continuing to do their work. Examples ranged from feeling like they received adequate reimbursement for time off for continuing education pursuits to being able to choose ergonomically appropriate chairs or other equipment. Those participants, who did not experience a supportive organizational and management structure or one that seemingly did not value their input and contributions, did not describe that as a barrier to continuing to work but rather more of an annoyance. None of the participants in our sample were able to identify a policy that explicitly supported aging workers. One participant said, “I don’t know that they’ve done anything to specifically make it more age friendly” while another said, “I don’t think that they’ve done anything as far as age differences.”

Discussion

Individual intrinsic factors play a major role in older nurses’ work ability and outlook for the future. Most nurses within the interviewed cohort anticipated continuing working at their current work for the next 5 to 10 years, barring personal health setbacks. Our findings are similar to a recent qualitative systematic review of older nurses’ experience of providing direct patient care in hospitals (Parsons, Gaudine, & Swab, 2018). In the 12-paper synthesis, one of the key findings was that nurses loved nursing and felt strongly that they identified with the profession. This theme is very similar to our overarching theme and nurses describing the joy they derived from working as a nurse. Further, the intrinsic rewards of the joy of nursing as described in our sample as a facilitator may be similar to the concept of rewards as theorized in the Effort-Reward Imbalance Model (ERI). The ERI model, which has been used extensively in other working populations to understand the effects of how work is organized, posits that an imbalance between effort (including both psychological and physical demands/obligations) and rewards (i.e., salary, esteem, job security) results in negative emotions and a sustained stress response, which may contribute to real or potential adverse health effects (Cooper & Quick, 2017).

Our study appears to be one of the few conducted in the urban northeast and confirms findings from studies previously conducted primarily in the southeast and southwest. From what we can infer based on existing studies, geography and setting (urban versus rural) does not appear to have a significant impact on older nurses’ work ability, further supporting the potency of individual level factors as facilitators to work ability.

Unit-based work factors facilitating work ability for aging nurses included working a preferred shift and schedule, including the number of hours worked per week. Several participants described their career trajectory, which lasted several decades, as it related to their shift, schedule, and full or part-time status. As they experienced different shifts and schedules and as personal situations evolved (e.g., marriage, young children at home), many described the importance of having flexibility in modifying their schedule or shift to meet their physical or home demands. Without that flexibility, many would not still be at the bedside or would be at a different institution or within a different unit/specialty. Findings from the European Nurses Early Exit Study (NEXT) support what our participants described; valuing nurses’ preferences for shift schedule is one way to potentially prevent nurses from leaving the profession early as well as promoting work ability (Galatsch, Li, Derycke, Müller, & Hasselhorn, 2013).

Interestingly, organizational policies regarding continuing education, conference travel, and other professional development was discussed but not deemed a factor related to work tenure. There was not a clear consensus from participants about how the organization could promote healthy aging at work or working longevity. It was somewhat concerning that many participants could not even identify one policy or practice that was implemented in their organization to assist aging workers. This poses a problem for workers within this organization if they do not know what supports may be available to them. The organization is also at risk for losing workers or having additional financial implications related illness/injury or turnover in aging workers. Further research on this topic across organizations may lead to different findings.

Implications for Administrators and Clinical Practice

Managers and administrators may give additional consideration to workplace policies for aging nurses in their units and within the organization. While all workers over 50 years have shown reduced tolerance for shift work, female nurses may be at greater risk for decreased work ability and increased illness with aging (Costa & Sartori, 2007). Thus, recommendations may include: reductions in night shift/rotating shift duties after age 50, choice in shift schedule and shift length, reduced workload, and increase in the frequency of health checks.

Occupational health nurses (OHN) can contribute their knowledge of aging workers to the retention of aging nurses through additional surveillance, intervention and coordination, when necessary. Some of the key physiologic considerations for aging nurses include vision, hearing, processing, and musculoskeletal flexibility; our study participants commented on issues they experienced within these key areas (Moore & Moore, 2014). OHN-led accommodations, such as larger font on work screens, ergonomic chairs and desks, and “light duty” options following musculoskeletal injury or surgery, for work within these domains has the potential to keep aging nurses at the bedside.

This study has several limitations. First, we used a convenience sample from one institution. However, we recruited from a wide range of unit specialties to achieve heterogeneity in work experiences in our sample. We were unable to recruit any men. While the nursing profession is still overwhelmingly female, especially the older cohorts, aging male nurses may have had a different experience than the female nurses. Racial/ethnic minority nurses were also underrepresented in the sample. Oversampling for male and minority participants should be a priority for future studies on this topic to allow for a more diverse cohort by race/ethnicity and gender. Also, this study did not focus on external factors (e.g. political, economic). Future studies that investigate broader populations and health care systems that may be subject to different external factors is warranted.

Overall, work ability in older nurses was rooted in largely personal, intrinsic factors versus unit-based work or organizational factors. Resilience, belief that age is just a number, and the personal relationships nurses develop with their patients keep aging nurses at the bedside. Managers with aging nurses on staff may consider additional attention to workers’ schedules, workload, and overall health to promote retention at the bedside. Consulting with occupational health nurses to provide additional surveillance and interventions to promote the health of aging workers may also prove effective in retaining aging nurses within an organization.

Figure 1. NIOSH Organization of Work framework and Level of Analysis.

Note. NIOSH=National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, *not explicitly discussed in this study.

References

- Auerbach DI, Chen PG, Friedberg MW, Reid R, Lau C, Buerhaus PI, & Mehrotra A (2013). Nurse-managed health centers and patient-centered medical homes could mitigate expected primary care physician shortage. Health Affairs, 32(11), 1933–1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer CS, Kovner CT, Obeidat RF, & Budin WC (2013). Positive work environments of early-career registered nurses and the correlation with physician verbal abuse. Nursing Outlook, 61(6), 408–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budin WC, Brewer CS, Chao Y, & Kovner C (2013). Verbal abuse from nurse colleagues and work environment of early career registered nurses. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 45(3), 308–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. (n.d.). Nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses requiring days away from work. Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/osh2.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). NIOSH topics. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/healthcare/

- Clarke SP (2007). Hospital work environments, nurse characteristics, and sharps injuries. American Journal of Infection Control, 35(5), 302–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper CL & Quick JC (Eds). (2017). The handbook of stress and health: A guide to research and practice (1st ed.). West Sussex, UK: Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Costa G, & Sartori S (2007). Ageing, working hours and work ability. Ergonomics, 50(11), 1914–1930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW (2007). Qualitative inquiry & research design (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Delloiacono N (2016). Origin of a musculoskeletal guideline: Caring for older workers. Workplace Health & Safety, 64(6), 262–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson VV (2013). How older workers with coronary heart disease perceive the health effects of work. Workplace Health & Safety, 61(11), 486–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson VV, Howe A, Deal J, & McCarthy MM (2012). The relationship of work, self-care, and quality of life in a sample of older working adults with cardiovascular disease. Heart & Lung: The Journal of Acute and Critical Care, 41(1), 5–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ervasti J, Kivimäki M, Dray-Spira R, Head J, Goldberg M, Pentti J, … Virtanen M (2016). Comorbidity and work disability among employees with diabetes: Associations with risk factors in a pooled analysis of three cohort studies. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 44(1), 84–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galatsch M, Li J, Derycke H, Müller BH, & Hasselhorn HM (2013). Effects of requested, forced and denied shift schedule change on work ability and health of nurses in Europe-Results from the European NEXT-Study. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomaa AE, Tapp LC, Luckhaupt SE, Vanoli K, Sarmiento RF, Raudabaugh WM, … Sprigg SM (2015). Occupational traumatic injuries among workers in health care facilities—United States, 2012–2014. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 64(15), 405. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths P, Dall’Ora C, Simon M, Ball J, Lindqvist R, Rafferty A-M, … Aiken LH (2014). Nurses’ shift length and overtime working in 12 European countries: The association with perceived quality of care and patient safety. Medical Care, 52(11), 975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen AB, Stayner L, Hansen J, & Andersen ZJ (2016). Night shift work and incidence of diabetes in the Danish Nurse Cohort. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 73(4), 262–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington L, & Heidkamp M (2013). The aging workforce: Challenges for the health care industry workforce. Aging, 2020, 115. [Google Scholar]

- Hruby A, Manson JE, Qi L, Malik VS, Rimm EB, Sun Q, … Hu FB (2016). Determinants and consequences of obesity. American Journal of Public Health, 106(9), 1656–1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller SM, & Burns CM (2010). The aging nurse: Can employers accommodate age-related changes? AAOHN Journal, 58(10), 437–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma C, & Stimpfel AW (2018). The association between nurse shift patterns and nurse-nurse and nurse-physician collaboration in acute care hospital units. Journal of Nursing Administration, 48(6), 335–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore PV & Moore RL (Eds.). (2014). Fundamentals of occupational and environmental health nursing: AAOHN Core Curriculum. Pensacola, FL: American Association of Occupational Health Nurses. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health. (2008). Work organization and stress-related disorders. Washington D.C: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson A, & Baptiste A (2004). Evidence-based practices for safe patient handling and movement. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 9(3), 4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons K, Gaudine A, & Swab M (2018). Older nurses’ experiences of providing direct care in hospital nursing units: A qualitative systematic review. JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports, 16(3), 669–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips JA, & Miltner R (2015). Work hazards for an aging nursing workforce. Journal of Nursing Management, 23(6), 803–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauter SL, Brightwell WS, Colligan MJ, Hurrell JJ, Katz TM, LeGrande DE, … Murphy LR (2002). The changing organization of work and the safety and health of working people. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2002-116/pdfs/2002-116.pdf

- Sofer D (2018). Nurses pass the baton: Exit baby boomers, enter millennials. The American Journal of Nursing, 118(2), 17–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stimpfel AW, & Aiken LH (2013). Hospital staff nurses’ shift length associated with safety and quality of care. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 28(2), 122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stimpfel AW, Brewer CS, & Kovner CT (2015). Scheduling and shift work characteristics associated with risk for occupational injury in newly licensed registered nurses: An observational study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 52(11), 1686–1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stimpfel AW, Sloane DM, & Aiken LH (2012). The longer the shifts for hospital nurses, the higher the levels of burnout and patient dissatisfaction. Health Affairs, 31(11), 2501–2509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thinkkhamrop W, & Laohasiriwong W (2015). Factors associated with musculoskeletal disorders among registered nurses: Evidence from the Thai Nurse Cohort Study. Kathmandu University Medical Journal, 13(3), 238–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinkoff AM, Johantgen M, Storr CL, Gurses AP, Liang Y, & Han K (2011). Nurses’ work schedule characteristics, nurse staffing, and patient mortality. Nursing Research, 60(1), 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinkoff AM, Le R, Geiger-Brown J, & Lipscomb J (2007). Work schedule, needle use, and needlestick injuries among registered nurses. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology, 28(2), 156–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinkoff AM, Le R, Geiger‐Brown J, Lipscomb J, & Lang G (2006). Longitudinal relationship of work hours, mandatory overtime, and on‐call to musculoskeletal problems in nurses. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 49(11), 964–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuomi K, Huuhtanen P, Nykyri E, & Ilmarinen J (2001). Promotion of work ability, the quality of work and retirement. Occupational Medicine, 51(5), 318–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg TIJ, Elders LAM, de Zwart BCH, & Burdorf A (2009). The effects of work-related and individual factors on the Work Ability Index: A systematic review. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 66(4), 211–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallis L (2015). OSHA gets serious about workplace safety for nurses. The American Journal of Nursing, 115(9), 13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Punnett L, McEnany GP, & Gore R (2016). Contributing influences of work environment on sleep quantity and quality of nursing assistants in long-term care facilities: A cross-sectional study. Geriatric Nursing, 37(1), 13–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]