Abstract

Objectives:

Vasomotor symptoms (VMS), commonly reported during menopausal transition, negatively affect psychological health and health-related quality of life (HRQoL). While hormone therapy is an effective treatment, its use is limited by concerns about possible harms. Thus, many women with VMS seek nonhormonal, nonpharmacologic treatment options. However, evidence to guide clinical recommendations is inconclusive. This study reviewed the effectiveness of yoga, tai chi and qigong on vasomotor, psychological symptoms, and HRQoL in peri- or post-menopausal women.

Design:

MEDLINE, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, EMBASE, CINAHL and the Allied and Complementary Medicine Database were searched. Researchers identified systematic reviews (SR) or RCTs that evaluated yoga, tai chi, or qigong for vasomotor, psychological symptoms, and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in peri- or post-menopausal women. Data were abstracted on study design, participants, interventions and outcomes. Risk of bias (ROB) was assessed and updated meta-analyses were performed.

Results:

We identified one high-quality SR (5 RCTs, 582 participants) and 3 new RCTs (345 participants) published after the SR evaluating yoga for vasomotor, psychological symptoms, and HRQoL; no studies evaluated tai chi or qigong. Updated meta-analyses indicate that, compared to controls, yoga reduced VMS (5 trials, standardized mean difference (SMD) −0.27, 95% CI −0.49 to −0.05) and psychological symptoms (6 trials, SDM −0.32; 95% CI −0.47 to −0.17). Effects on quality of life were reported infrequently. Key limitations are that adverse effects were rarely reported and outcome measures lacked standardization.

Conclusions:

Results from this meta-analysis suggest that yoga may be a useful therapy to manage bothersome vasomotor and psychological symptoms.

1. Introduction

Menopause is often accompanied by an increase in bothersome vasomotor symptoms (VMS), such as hot flashes and psychological symptoms and a decrease in quality of life (QoL). VMS are experienced by 80% of women.1 Depending on their frequency and duration coexistence of sleep problems,2 and the degree of interference with daily life activities or job-related activities,1 VMS may negatively affect QoL.3,4 Studies also suggest that psychological symptoms, including anxiety and mood disturbances, may be more common among women in the peri- and post-menopausal periods, in general, and in women with bothersome menopause symptoms, in particular.5,6

Hormone therapy (HT) is an effective treatment for reducing VMS, but use of this therapeutic approach must be individualized by weighing benefits with known risks, such as cardiovascular events, or uterine and breast cancers.7 A common recommended strategy is to use HT with the “lowest effective dose for the shortest duration that is needed”.8,9 However, the median total duration of the menopausal transition is more than 7 years.10 Given the potential risks posed by long-term HT use and the simultaneous need to alleviate persistent VMS, nonhormonal treatment may be the only option for a substantial number of women experiencing VMS. Thus, identifying safe and effective alternatives to HT that relieve VMS, reduce depressive and anxiety-related symptoms, and improve quality of life for women is important to increase options for patient-centered care.

Many women are already using nonpharmacologic, nonhormonal therapies to manage VMS, 11–14 including mind and body practices, such as yoga. Studies indicate that yoga, tai chi, and qigong may improve health-related quality of life (HRQoL)15,16 and help to manage conditions independent of menopause, such as anxiety,17 sleep disturbance,18–20 and mood disorders.21,22 Since 2009, two systematic reviews (SRs) examined the impact of yoga on menopause-related symptoms, including vasomotor and psychological symptoms.23,24 While these reviews found negligible effects of yoga for VMS, one SR found moderate evidence for short-term effects of yoga on psychological symptoms among women in the menopausal transition.23 No SRs examined tai chi or qigong for VMS, psychological symptoms or HRQoL. Moreover, methodological limitations of these SRs, including methods that did not account for false precision and a lack of conceptually similar outcomes across studies, may have impeded the ability to draw conclusions.

Growing interest in safe alternatives to alleviate long-term menopausal symptoms has prompted research on nonpharmacologic, nonhormonal therapies in menopausal women and recommendations are beginning to emerge. In 2015, the North America Menopause Society released a position statement with recommendations for the nonhormonal management of menopause-associated symptoms; these recommendations were based on graded evidence of the literature rather than a formal systematic review. However, due to inconclusive evidence about the effect of yoga, yoga is not currently a recommended as a therapy to alleviate VMS.25 Yet, yoga is an appealing treatment that is commonly used, widely available, adaptable to most health conditions and physical limitations, and can be done at home. Therefore, more evidence about the effectiveness of yoga for common and bothersome VSM, psychological symptoms, and HRQoL is needed to guide treatment recommendations. To achieve this objective, our study applies an umbrella review, or a review of reviews,26,27 methodology to summarize and update the evidence from prior SRs on the use of yoga, tai chi and qigong compared with active and inactive controls for the treatment of menopause-associated VMS, psychological symptoms, and HRQoL among peri- and post-menopausal women.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

This paper is part of a larger umbrella review that examined the evidence about the impact of multiple categories of nonpharmacologic, nonhormonal treatments on menopausal symptoms. Given that interventions may operate through distinct mechanisms on health outcomes, we chose to group interventions into like categories (i.e. yoga/tai/qigong; acupuncture; relaxation/meditation; and physical activity) and write targeted, conceptually coherent papers about intervention categories for which there was updated evidence. This paper is distinct from the full report because it focuses exclusively on the implications of yoga/tai chi/qigong as a therapy to manage menopause-related symptoms. Appendix A. Intervention Definition. Appendix B. Flow Diagram. The full review report is available at www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp. The PROSPERO registration number for the larger review is CRD420160293351.

We followed a standard protocol28 for all steps of this review. We supplemented the umbrella review of SRs by evaluating randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published after the most recent good-quality SR. The research question for this SR was developed after a topic refinement process that included a preliminary review of published peer-reviewed literature, discussion with internal partners and investigators, and consultation with content experts and key stakeholders.

2.2. Data sources and searches

In consultation with an expert librarian, we conducted searches of MEDLINE (via PubMed) and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews published from January 2010 through November 2015 for SRs, as well as searches of PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL, and the Allied and Complementary Medicine Database from January 2012 through February 2016 for RCTs. We used MeSH keywords and selected free text terms for the interventions and health conditions of interest as well as terms for SRs and RCTs.

2.3. Study selection

We included SRs and RCTs that evaluated an eligible intervention for perimenopause or post-menopausal women. We defined perimenopause as amenorrhea for greater than 60 days in the past 12 months; post menopause is defined as being without a menstrual cycle due to spontaneous or surgical reasons for the preceding 12 months.29,30 We accepted the definition of VMS, psychological symptoms, and HRQoL used by SR authors. For RCTs, we considered studies with VMS defined as: self-identified “bothersome” hot flashes that occurred at least 6 days in the previous 2 weeks,10 or hot flashes associated with impairment in role, social, emotional, or physical functioning. For psychological symptoms, we considered RCTs that used scales to measure depression or anxiety. For HRQoL, we accepted scales that we determined measured the underlying construct of general QoL or menopause-specific QoL by conducting a comparative review of the scale items and universally accepted QoL measures. We included only full journal articles and English language publications. All eligible SRs along with relevant umbrella and narrative reviews identified during citation screening were reviewed for additional relevant RCTs. Appendix C: Search Strategies.

Using pre-specified inclusion/exclusion criteria (Table 1), two reviewers appraised titles and abstracts of SRs and RCTs identified through our primary search for potential studies relevant to the key question. In brief, eligible articles addressed yoga/tai chi/qigong in peri- or post-menopausal women who experienced bothersome VMS, reported effects on VMS, HRQoL, psychological symptoms, or adverse effects, and used a systematic review or RCT design. Articles included by either reviewer underwent full-text screening. Disagreements on inclusion or exclusion were resolved by discussion or by a third reviewer throughout the selection, data extraction and quality assessment process.

Table 1.

SR and RCT exclusion and inclusion criteria.

| Study Characteristic | Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Population | Perimenopausal and postmenopausal women who are experiencing bothersome VMS. Perimenopause is defined as amenorrhea for > 60 days in the past 12 months; post menopause is defined as being without a menstrual cycle due to spontaneous or surgical reasons for the preceding 12 months. Bothersome VMS is defined as any of the following: • Self-identified “bothersome” hot flashes • Moderate to severe VMS as defined by the FDA63 • Hot flashes that occur for at least 6 days in the previous 2 weeks10 • Hot flashes associated with functional impairment (e.g., impairment in role, social, emotional, or physical functioning) |

| Interventionsa | • Yoga, tai chi, qigong (as defined by study investigators) |

| Comparators | Any inactive control (waitlist, attention, information control, or unenhanced usual care) or active comparator (including hormone treatments, antidepressants or other pharmacotherapies, dietary supplements, health education, and alternative forms of exercise) |

| Outcomes | • Frequency and severity of VMS • Overall and condition-specific health – related quality of life • Psychological well-being (i.e., depressive or anxiety symptoms) and sleep quality, prioritizing validated scales over non-validated scales or single-symptom measures (e.g., frequency of hot flashes) • Serious adverse effects and adverse effects |

| Timing | • For SRs, timing of outcome assessments as specified by the review • For RCTs, outcomes assessed at > 60 days after treatment assignment |

| Setting | Outpatient or community settings (and mixed settings inclusive of outpatient/community settings) |

| Study design | Included: SRs and RCTs that evaluate an eligible intervention for VMS that is associated with perimenopause or post menopause Excluded: SRs of complementary and alternative therapies in general without a specific focus on the intervention of interest, and umbrella reviews |

| Publication type | Included: Full articles published in peer-reviewed journals from January 2010 to November 2015 for SRs, or from January 2012 to February 2016 for RCTs Excluded: Abstracts and dissertations |

Intervention definitions are in Table 1.

Abbreviations;: RCT = randomized controlled trial; SR = systematic review; VMS = vasomotor symptoms.

2.4. Data extraction and quality assessment

Data were abstracted into a customized DistillerSR database by one reviewer, and subsequently over-read by a second reviewer. Data elements abstracted included descriptors to characterize the type of study, study population, intervention, comparator, outcomes reported, study quality, and author conclusions.

Two reviewers assessed the quality of SRs and RCTs. For SRs, we used the following key quality criteria, adapted from ROBIS31 and AMSTAR: search methods: adequate for replication and comprehensive, selection bias avoided, data abstracted reliably, characteristics of primary literature reported and quality assessed appropriately, results synthesized using appropriate methods, publication bias assessed, conflict of interest reported, and conclusions supported by results. Based on these criteria, SRs were categorized as good, fair, or poor quality. Good- and fair-quality SRs should provide sufficient information to assess the strength of the body of evidence using the GRADE criteria,32 which include 4 major domains of risk of bias (directness, consistency, precision, and reporting bias. Poor-quality SRs were excluded from our review. For newly identified RCTs, we used the Cochrane Collaboration’s risk of bias (ROB) tool,33 which categorizes biases by 6 domains (selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, reporting bias, and other bias) and makes a summary ROB assessment (high, low, or unclear). Appendix D: Quality Criteria.

2.5. Data synthesis

We analyzed and summarized the results from the only SR identified that pertained to yoga, tai chi or qigong.34 We examined the SR for relevant subgroup analyses, including concurrent use of HT, effects in women with and without breast cancer, perimenopausal and postmenopausal women, and women with surgical versus natural menopause. We confirmed (and at times corrected) SR reports of trial characteristics, outcomes data, and data included in meta-analyses (MA) that we updated.

2.6. Statistical analysis

As a framework for determining whether a new quantitative synthesis is needed, we considered the number of new studies, the sample size, and the strength of evidence (SOE) domains.32 When an updated or new MA was indicated and feasible,28 we computed summary estimates of effect for each intervention using end-of-treatment outcomes. When means and measures of dispersion were not reported in the text, they were approximated from figures with the use of Engauge Digitizer.35 We imputed missing control group standard deviations (SDs) in two studies36,37 (and for 1 outcome measure—psychological symptoms) by using the maximum of all available SDs from other arms in the same study, which were measured on the same scale. To avoid the potential for false precision and preserve all trial data, for 3-arm studies with 2 control groups (e.g. wait list and attention control), we compared yoga to the average effect of the two control arms.26

We used R statistical software version 3.1.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) with the metafor package38 to calculate summary random-effects model estimates of effect utilizing Knapp and Hartung adjustment of standard errors of the estimated coefficients.39,40 This method provides a more precise 95% confidence interval for meta-analyses with fewer than 20 studies and is an improvement on the Der Simonian and Laird approach used in the SR by Cramer and colleagues.41 Since outcomes were measured across the trials using different instruments, outcome measures were combined using standardized mean differences (SMDs). The SMD is a measure of effective size and was calculated by dividing the difference in mean values by the pooled SDs of the 2 groups. SMDs of >0.2 can be considered small treatment effects; 0.5, moderate effects; and >0.8, large effects.42 Consistency of findings across individual studies was assessed by Cochrane’s Q and the I2 statistic.

2.7. Rating the body of evidence

We followed the approach recommended by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) to evaluate overall quality of evidence assessing 4 domains: risk of bias, consistency, directness, and precision.43 We used results from MAs when evaluating consistency (forest plots and tests for heterogeneity), precision (CIs), and strength of association (SMDs). These domains were considered qualitatively and a summary rating of high, moderate, low, or insufficient strength of evidence (SOE) was assigned after discussion by 2 investigators.

3. Results

3.1. Study characteristics and risk of bias

We identified a single eligible SR23 that included 5 RCTs 36,44–47 evaluating the effect of yoga compared with both inactive and/or active comparators on VMS in 582 participants. This SR, published in 2012, was judged to be of high quality. Yoga interventions were delivered in 34–40 sessions over 8 weeks to 4 months. All 5 trials included yoga postures and meditation; 4 included breathing exercises, and 2 included lifestyle lectures. The SR determined risk of bias was low for 2 RCTs 46,47 and high for 3 RCTs.36,44,45 Key quality issues included lack of participant/provider blinding, inadequate intention-to-treat analysis, and inadequate disclosure of the full study protocol. We found no SR or RCTs that examined the effect of tai chi or qigong on VMS, psychological symptoms, or HRQoL among women in menopausal transition. Table 2: SR Characteristics.

Table 2.

Systematic Review Study Characteristics: Cramer et al., 2012.23

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Systematic review | |

| Number of included trials | 5 |

| Number of patients | 582 |

| Date of SR literature search | April 2012 |

| Mean age range in years (median) | 45.6 to 54.9 (49.0) |

| RCTs included in the SR | |

| Study years | 2007–2011 |

| Countries | |

| USA | 2 |

| India | 2 |

| Brazil | 1 |

| Population | |

| Perimenopausal or postmenopausal | 4 |

| Women who had completed treatment for breast cancer | 1 |

| Yoga interventions | |

| Yoga postures | 5 |

| Breathing | 4 |

| Meditation | 5 |

| Lifestyle lectures | 2 |

| Planned number of yoga treatments | 34–40 |

| Length of intervention period | 8 weeks to 4 months |

| Training of yoga instructors | |

| Certified and experienced | 2 |

| Not reported | 3 |

| Comparisons | |

| Inactive—waitlist | 4 |

| Active—walking, stretching, lifestyle lectures | 3 |

| Inactive and active (3-arm trial) | 2 |

| Outcomes | |

| Total menopause symptoms | 3 |

| Vasomotor symptoms | 3 |

| Psychological symptoms | 5 |

| Sleep/insomnia | 0 |

| Adverse effects of yoga | 1 |

| Timing of last outcome assessment after randomization | |

| Short-term (taken closest to 12 weeks after randomization) | 5 |

| Long-term (taken closest to 12 months after randomization) | 1 |

We also identified 3 new relevant RCTs37,48,49 published after 2012 that assessed the impact of yoga on the frequency and severity of hot flashes, and quality of life outcomes among 345 perimenopausal or postmenopausal women. This represented a 60% increase in the number of women assessed in the previous SR. Two RCTs were judged to be of poor quality.37,48 Of primary concern was the use of a weak control (waitlist), and unclear or high risk approaches to random sequence generation, allocation concealment, and blinding. The third RCT was judged to be of moderate quality due to unclear risk related to participant blinding and the use of subjective outcome measures.49 Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Risk of bias (ROB) of two newly identified RCTs.

Newly identified RCTs were carried out in Thailand48 and the USA37,50; and included patients recruited in community settings. In these studies, integral yoga, Viniyoga, or a Rusie Dutton course were compared with inactive controls. All approaches incorporated deep breathing, physical postures, and relaxation. Courses lasted 10, 12 or 13 weeks and sessions were held on a weekly basis for 90 min. In one RCT, yoga was compared with a wait-list control,48 in another yoga was compared to an attention control50 and in the third with a 2-armed control (health-and-wellness and waitlist).37 Avis and colleagues assessed VMS, psychological symptoms, and HRQoL using the Daily Hot Flash Diary, the CESD-10, and the Global Quality of Life Scale at 5 and 10 weeks in one RCT.37 In the Ngowsiri et al. trial, vasomotor and psychological symptoms were assessed using subscales from the Menopause-specific Quality of Life instrument (MENQOL-Thai version) at 12 weeks.48 Newton et al. assessed VMS using the Daily Hot Flash Diary and depressive symptoms using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-8).50 Table 3: RCT Characteristics.

Table 3.

Newly Identified RCT Study Characteristics.

| Study Country |

Population # Women randomized Type of menopause # Hot flashes Mean age (range) |

Intervention Category/type Session frequency/duration |

Comparator Category/type Session frequency/duration |

General Outcomes Instruments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avis 201437 | Yoga: 18 | Yoga: integral yoga, adapted from Satchidananda, with breathing, relaxation, and postures | Attention: health and wellness education | • Frequency/severity of hot flashes (DDHF) • Sleep quality (Global Sleep Quality index) • Anxiety (HSCL) |

| USA | Health and wellness: 19 Waitlist: 17 Natural; surgical; and women treated for breast cancer (not currently receiving treatment) ≥ 4 hot flashes per day on average for ≥ 4 weeks and ≥ 2 months since last menses Yoga: 53.5 (0.7) Health and wellness: 52.8 (0.7) Waitlist: 53.5(0.7) |

1 group session per week for 10 weeks; 2–3 home practice per week for 15 min 90-min duration | 10 weekly educational classes; materials to read at home (to match time spent in home practice among individuals in intervention group) 90 min duration Inactive comparator: Waitlist; no initiation of new therapies for hot flashes or participation in classes for 10 weeks |

• Depressive symptoms (CESD) • Global quality of life (SF-36) |

| Ngowsiri 201448 |

Rusie Dutton: 24 | Yoga: Rusie Dutton | Inactive comparator: Wait list; | Menopause specific quality of life subscales (Thai version of MENQOL subscales: vasomotor, psychological) |

| Thailand | Waitlist: 26 Type of menopause NR Mild to moderate menopause symptoms per Self-Assessment for Menopause Symptoms (developed from MRS) Yoga: 52.9 (4.3) Waitlist: 50.7 (3.6) |

1 group class per week for 13 weeks; 2 home practice per week 90-min duration |

offered class 13 weeks after post-test assessment was completed | |

| Newton 201449 | Viniyoga: 107 | Yoga: Viniyoga | Inactive comparator: Usual activity/attention control; part of 2 × 3 factorial design trial, participants in yoga/control groups were cross randomized to receive placebo/omega-3 capsules | Hot flash/night sweat frequency and bother (Hot flash Daily Diary); depressive symptoms (PHQ-8) |

| USA | Attention control: 142 Type of menopause: natural; surgical ≥14 hot flashes/night sweats per week; VMS rated as bothersome or severe on 4 or more occasions per week per daily diary Yoga 54.3 (3.9) Control 54.2 (3.5) |

90-min duration 1 group class per week for 12 weeks; daily 20-minute home practice |

Offered 3-h yoga workshop or one-month gym member at study end | |

3.2. Statistical results

3.2.1. VMS

The authors of the SR analyzed the overall effects of outcomes and conducted subgroup analyses comparing yoga to an active control and to an inactive control.23 In the overall effects MA for VMS, SR authors conducted a MA of 2 RCTs and found that yoga, compared with exercise44 and waitlist control45 was not associated with short-term benefits for alleviating VMS (2 trials, SMD −0.04, 95% CI −0.68 to 0.60, I2 = 81%). A subgroup analysis compared yoga to the exercise control arms only44,45 and showed that yoga did not reduce VMS (2 trials, SMD −0.13, 95% CI −0.58 to 0.33, I2 = 67%).

Of the 3 new RCTs, one found significant differences in pre/post scores on the vasomotor subscale of the MENQOL (p = 0.04).48 The other 2 RCTs did not find any statistically significant effects of yoga on VMS.37

We updated the MA in the SR to examine the overall effect of yoga compared with active and inactive controls collectively on hot flash severity using data from 3 new RCTs and 2 RCTs included in the SR.44,45 Measures used in these studies included the Greene Climacteric Scale,44,45 MENQOL Thai version subscale,48 and the Daily Hot Flash Diary.37 Contrary to the SR, results from our updated MA suggest that yoga is associated with a significant reduction in hot flash severity (5 trials, SMD −0.27, 95% CI −0.49 to −0.05, I2 = 0.0%, Cochrane’s Q = 3.2 p = 0.52). Fig. 2. Strength of evidence for the effects of yoga versus control (5 trials, n = 545) on VMS was judged as low. Appendix E: Strength of Evidence.

Fig. 2.

Forest plot for effect of yoga versus control on hot flash severity.

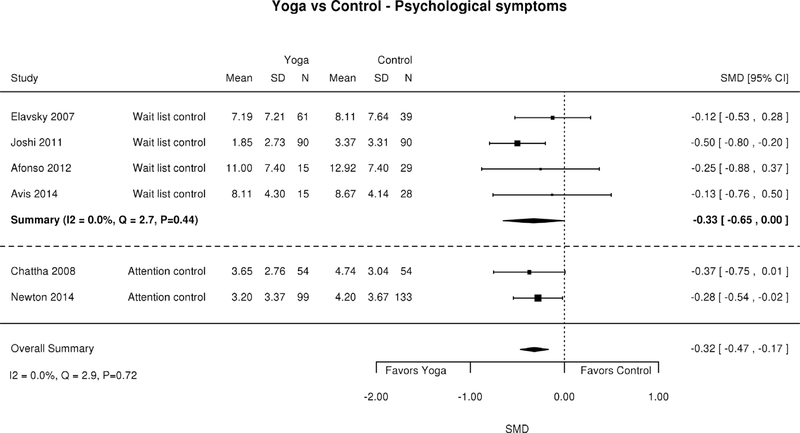

3.2.2. Psychological symptoms

In the SR,23 authors conducted a MA of the overall effect of yoga on psychological symptoms compared with active and inactive controls.36,44–46 Two of the RCTs were 3-armed trials,36,45 but only data from participants from the waitlist control groups were used. Yoga improved psychological symptoms (4 trials, SDM −0.37; 95% CI −0.67 to −0.07, I2 = 0.52).23

Findings from the SR subgroup analyses suggest that yoga had no effect on psychological symptoms regardless of control group used: inactive control 36,45,46 (3 trials, SDM −0.36; 95% CI −0.81 to −0.09, I2 = 0.68), attention control 36,44,45 (3 trials, SDM 0.10; 95% CI −0.43 to 0.62, I2 = 0.75).23

Of the newly identified RCTs, one found significant reductions in psychological symptoms at 12 weeks as measured by the pre/post scores on the MENQOL Thai version subscale (p < 0.001).48 Newton et al. also found positive effects of yoga on depressive symptoms at 12 weeks measured by pre/post scores on the PHQ-8 (p = 0.03)50 while Avis et al. found no treatment effect.37

We updated the MA in the SR to: 1) include data from two newly identified RCTs 37,50 and 2) use the results from the Beck Depression Inventory instead of the Greene Climacteric Scale presented in one RCT identified by the SR.45 Where possible, the Beck Depression Inventory was used because it is a validated measure of psychological symptoms. Measures included the Beck Depression Inventory,36,45 Greene Climacteric Scale,44 the CESD-10,37 and the Menopause Rating Scale.46 One of the newly identified RCTs48 was not included because the psychological subscale of the MENQOL Thai version did not fully represent the construct of psychological symptoms. Consistent with the prior SR results, yoga compared with control was associated with a decrease in psychological symptoms (6 trials, SDM - 0.32; 95% CI - 0.47 to −0.17, I2 = 0.0%, Cochrane’s Q = 2.9 p = 0.72). Fig. 3. Strength of evidence for the effects of yoga versus control on psychological symptoms (6 trials, n = 707) was moderate.

Fig. 3.

Forest plot for effect of yoga versus control on psychological symptoms.

3.2.3. Health-related quality of life and adverse events

Heath-related quality of life was not examined frequently. Of the 5 RCTs identified by the SR, only one RCT used a scale (the Greene Climacteric Scale) that by our judgment assessed the concept of quality of life.45 In this RCT, yoga compared to a walking attention control and a waitlist control 45 was not found to have an impact on HRQoL. Adverse effects were reported in only two RCTs and were infrequent. 36,50

4. Discussion

We evaluated the effect of yoga, tai chi, and qigong among peri- and post-menopausal women on VMS, psychological symptoms, HRQoL, and adverse events. We did not identify any SRs or RCTs on tai chi and qigong. Our review identified 1 good-quality SR and 3 new RCTs on yoga, which allowed updated MAs to estimate the effect of yoga on VMS, psychological symptoms, and HRQoL. Almost all studies reported effects on VMS frequency or severity and psychological symptoms; fewer reported effects on HRQoL and adverse events. MA results from the SR suggest that short-term effects of yoga are not significantly associated with changes in VMS, but do improve psychological symptoms.23 In contrast to previous findings, our updated MA found that yoga had small to moderate benefits on reduced hot flash severity and psychological symptoms. Yoga demonstrated no impact on quality of life; adverse events were rare and often not reported. Our results likely differ from those in previous SRs because of the addition of the 3 new RCTs (representing a 60% increase in the number of women assessed) and because we applied different analytical approaches to overcome past study limitations. Specifically, we used a treatment effect that adjusted for baseline differences in symptom severity,45 applied an adjustment for standard errors to protect against false precision,41 analyzed conceptually similar outcomes across studies, and for 3-arm trials we analyzed yoga against the average effect of two control groups.26

4.1. Limitations

The use of many different outcome measures across trials required us to report standardized mean differences, which are clinically difficult to interpret. A more readily interpretable outcome would be the proportion of women achieving the minimum clinically important response. This was especially true for HRQoL measures, with the additional caveat that there is no universally accepted HRQoL assessment instrument specific to menopause symptoms. Authors of the SR considered symptom inventories or functional status questionnaires as health-related or menopause-specific QoL instruments. We used the same terms reported by the authors of the SR, with the understanding that the underlying constructs measured are not likely to be truly health-related or menopause-specific QoL.

4.1.1. Specific to umbrella review

The novel approach of supplementing a review of reviews with findings from recently published RCTs allowed us to synthesize, both quantitatively and qualitatively, the most current information on yoga as a nonpharmacologic, nonhormonal intervention for VMS. A significant limitation to this approach is that we relied on the SR authors’ judgments on risk of bias for individual trials and the appropriateness of their search strategies, eligibility criteria, and synthesis of the evidence. We also limited our review to English-language publications, which may have excluded potentially informative evidence.

4.1.2. Specific to the trials

Most of the RCTs included in our report were relatively small, short-term trials and we are unable to determine whether observed effects might have persisted. Adverse events were rarely reported. All trials used self-report assessments and most did not mask participants to intervention allocation, thereby introducing the risk that patients allocated to the active interventions might exaggerate clinical improvement. Neither trial compared yoga to more than one active control, which could have informed clinical decision-making for patients or healthcare providers faced with deciding among various therapeutic options. Both trials used usual care or waitlist controls, which do not control for nonspecific effects of a given intervention, and as such do not provide insights about an intervention’s potential mechanisms of action. However, usual care controls are appropriate for trials that aim to inform patients or healthcare providers on outcomes of an intervention compared to no intervention.51 Yet, trials that include a usual care arm introduce a risk of bias, leading to either overestimation or underestimation of the true effect size of an intervention.52

4.2. Strength of evidence (SOE)

We found evidence that yoga compared to controls improves VMS (low SOE) and psychological symptoms (moderate SOE). There was not sufficient evidence to assess the effect of yoga for HRQoL (insufficient SOE). The SOE for adverse effects was rated insufficient because of inconsistent reporting. No trials compared yoga with active interventions such as HT or gabapentin, and yoga was not compared with antidepressants. No trials evaluated tai chi or qigong.

4.3. Research gaps/future research

Despite evidence of benefit from yoga, larger, higher quality trials comparing yoga to active controls are needed. Moreover, little is known about the effect of distinct types of yoga and whether some are more effective than others. Comparative effectiveness trials would be more likely to inform policy and clinical decision-making than placebo-controlled effectiveness trials. This may be especially true in the search for alternatives to pharmacologic approaches for managing menopause symptoms, where clinical effectiveness outcomes may need to be weighed against other outcomes of importance to women, healthcare providers, and policymakers, such as potential harm, cost, overall utility, and women’s’ preferences. Further, studies are needed to assess the effectiveness of yoga as an adjunctive treatment, since HT may not resolve all VMS or address psychological menopause-related symptoms. Finally, negative effects and duration of effects beyond end of treatment were rarely examined; future studies that measure these factors are needed. Since our search, one additional RCT was published showing that yoga compared with attention and inactive controls reduced menopause symptoms and psychological symptoms and improved HRQoL after 12 weeks (p < 0.05 for 3-way comparison on all three outcomes).53

4.4. Implications for practice and policy

VMS are highly prevalent among women in the menopausal transition.54 Clinical practice guidelines often recommend HT for women with VMS based on its known efficacy,8,9,55 but HT is contraindicated for some women and has known risks.56 Additionally, pharmacologic options may have short-term and sometimes long-term adverse effects.56 Further, estimates suggest that since findings from the Women’s Health Initiative Study (WHI) were published, the number of women who received HT related office visits in the US decreased by more than 60%.57 As a result, millions of women may be left without an alternative to manage bothersome menopause symptoms; thus, identifying effective nonpharmacologic, nonhormonal therapies is imperative. Complementary and alternative therapies are appealing as an acceptable and potentially cost-effective alternative to existing standard therapies.58,59 Yoga, with small to moderate benefits for vasomotor and psychological symptoms, might be an acceptable therapy for women in the menopausal transition. Yoga improves HRQoL and psychological symptoms and is used by older adults and more frequently by women compared with men.60–62 Our updated analysis shows benefit for yoga; and these updated results should be taken into consideration when making clinical or policy recommendations.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review builds on the existing evidence base by examining new trials and applying improved analytical methods. In contrast to previous reviews, our MAs support yoga for reducing menopause-related vasomotor and psychological symptoms in peri- or post-menopausal women. It is possible that improvements in vasomotor and psychological symptoms could impact women’s activities and HRQoL. The safety of the yoga interventions evaluated in this review has not been rigorously examined, but there is no clear signal for a significant potential for harm.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the editorial support of Liz Wing, MA, Senior Science Writer, Duke Clinical Research Institute.

Funding

This work was supported by Veteran Affairs Health Services Research and Development Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (ESP 09-010) and Veteran Affairs Health Services Research & Development (VA OAA HSR&D PhD Fellowship TPH 21-000 (Megan Shepherd-Banigan); VA HSRD CDA #13-263 (Karen Goldstein). This manuscript is based on research conducted by the Evidence-based Synthesis Program (ESP) Center located at the Durham VA Medical Center, Durham, NC, funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Quality Enhancement Research Initiative. The study sponsors had no role in designing the study, collecting, analyzing, or interpreting the data, writing the manuscript, or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

None.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this document are those of the author(s) who are responsible for its contents; the findings and conclusions do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government. Therefore, no statement in this article should be construed as an official position of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

This paper is part of a larger project undertaken by the Evidence-based Synthesis Program (ESP) Center at the Durham Veterans Affairs (VA) Healthcare System in Durham, NC. The full preliminary report will be published on US Department of Veteran Affairs Health Services Research & Development Evidence-based Synthesis Program at: http://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/reports.cfm

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2017.08.011.

The PROSPERO registration number is CRD42016029335.

References

- 1.Woods NF, Mitchell ES. Symptoms during the perimenopause: prevalence, severity, trajectory, and significance in women’s lives. Am J Med. 2005;118B(Suppl 12):14–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thurston RC, Bromberger JT, Joffe H, et al. Beyond frequency: who is most bothered by vasomotor symptoms? Menopause. 2008;15:841–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avis NE, Colvin A, Bromberger JT, et al. Change in health-related quality of life over the menopausal transition in a multiethnic cohort of middle-aged women: study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. Menopause. 2009;16:860–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ayers B, Hunter MS. Health-related quality of life of women with menopausal hot flushes and night sweats. Climacteric. 2013;16:235–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Llaneza P, Garcia-Portilla MP, Llaneza-Suarez D, Armott B, Perez-Lopez FR. Depressive disorders and the menopause transition. Maturitas. 2012;71:120–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen LS, Soares CN, Vitonis AF, Otto MW, Harlow BL. Risk for new onset of depression during the menopausal transition: the Harvard study of moods and cycles. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:385–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.North American Menopause Society. The 2012 hormone therapy position statement of the North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2012;19:257–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stuenkel CA, Davis SR, Gompel A, et al. Treatment of symptoms of the menopause: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:3975–4011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 141: management of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:202–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Avis NE, Crawford SL, Greendale G, et al. Duration of menopausal vasomotor symptoms over the menopause transition. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:531–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taylor M. Complementary and alternative approaches to menopause. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2015;44:619–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gartoulla P, Davis SR, Worsley R, Bell RJ. Use of complementary and alternative medicines for menopausal symptoms in Australian women aged 40–65 years. Med J Aust. 2015;203(146) 146e.141–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gentry-Maharaj A, Karpinskyj C, Glazer C, et al. Use and perceived efficacy of complementary and alternative medicines after discontinuation of hormone therapy: a nested United Kingdom Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening cohort study. Menopause. 2015;22:384–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Complementary, Alternative, or Integrative Health: What’s In a Name? 2017; 2017. [Available at: https://nccih.nih.gov/health/integrative-health. (Accessed March 10, 2016)].

- 15.Kelley GA, Kelley KS. Meditative movement therapies and health-related quality-of-life in adults: a systematic review of meta-analyses. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0129181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun J, Buys N. Community-based mind-body meditative Tai Chi program and its effects on improvement of blood pressure, weight, renal function, serum lipoprotein, and quality of life in chinese adults with hypertension. Am J Cardiol. 2015;116:1076–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hofmann SG, Andreoli G, Carpenter JK, Curtiss J. Effect of hatha yoga on anxiety: a meta-analysis. Journal of Evidence-Based Medicine. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sarris J, Byrne GJ. A systematic review of insomnia and complementary medicine. Sleep Med Rev. 2011;15:99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Attarian H, Hachul H, Guttuso T, Phillips B. Treatment: of chronic insomnia disorder in menopause: evaluation of literature. Menopause. 2015;22:674–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang F, Eun-Kyoung Lee O, Feng F, et al. The effect of meditative movement on sleep quality: A systematic review. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2015;30:43–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cramer H, Lauche R, Langhorst J, Dobos G. Yoga for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Depression and Anxiety. 2013;30:1068–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hempel S, Taylor S, Solloway M, et al. Evidence Map of Tai Chi. VA Evidence-based Synthesis Program Reports. Washington, DC: Department of Veteran Affairs; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cramer H, Lauche R, Langhorst J, Dobos G. Effectiveness of yoga for menopausal symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2012;2012:863905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee MS, Kim JI, Ha JY, Boddy K, Ernst E. Yoga for menopausal symptoms: a systematic review. Menopause. 2009;16:602–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.The North American Menopause Society. Nonhormonal management of menopause-associated vasomotor symptoms: 2015 position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2015;22:1155–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Becker LA, Oxman AD. Chapter 22: Overviews of reviews In: Higgins JPT, Green S, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration. 2011; 2011. [Available at: www.cochrane-handbook.org (Accessed October 21, 2015. 2011)]. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ioannidis JP. Integration of evidence from multiple meta-analyses: a primer on umbrella reviews, treatment networks and multiple treatments meta-analyses. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2009;181:488–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goldstein KM, McDuffie JR, Shepherd-Banigan M, et al. Nonpharmacologic, non-herbal management of menopause-associated vasomotor symptoms: an umbrella systematic review (protocol). Syst Rev. 2016;5:56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joffe H, Guthrie KA, LaCroix AZ, et al. Low-dose estradiol and the serotonin-nor-epinephrine reuptake inhibitor venlafaxine for vasomotor symptoms: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1058–1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harlow SD, Gass M, Hall JE, et al. Executive summary of the Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop + 10: addressing the unfinished agenda of staging reproductive aging. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:1159–1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Whiting P, Savovic J, Higgins JP, et al. ROBIS: A new tool to assess risk of bias in systematic reviews was developed. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, et al. GRADE guidelines: 1: Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:383–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011:343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robinson KA, Chou R, Berkman ND, et al. Twelve recommendations for integrating existing systematic reviews into new reviews: EPC guidance. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Engauge Digitizer (software package). Available at: http://markummitchell.github.io/engauge-digitizer/ (Accessed February 1, 2016).

- 36.Afonso RF, Hachul H, Kozasa EH, et al. Yoga decreases insomnia in postmenopausal women: a randomized clinical trial. Menopause. 2012;19:186–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Avis NE, Legault C, Russell G, Weaver K, Danhauer SC. Pilot study of integral yoga for menopausal hot flashes. Menopause. 2014;21:846–854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Viechtbauer W Conducting Meta-Analyses in R with the Metafor Package. 2010; 2010. Available at: https://www.jstatsoft.org/article/view/v036i03 (Accessed April 6, 2016. 2010).

- 39.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Knapp G, Hartung J. Improved tests for a random effects meta-regression with a single covariate. Stat Med. 2003;22:2693–2710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cornell JE, Mulrow CD, Localio R, et al. Random-effects meta-analysis of inconsistent effects: a time for change. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:267–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cohen J Hillsdale NJ, ed. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed L. Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014. [Available at: https://ahrq-ehc-application.s3.amazonaws.com/media/pdf/cer-methods-guide_overview.pdf (Accessed July 16, 2015)]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chattha R, Raghuram N, Venkatram P, Hongasandra NR. Treating the climacteric symptoms in Indian women with an integrated approach to yoga therapy: a randomized control study. Menopause. 2008;15:862–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Elavsky S, McAuley E. Physical activity and mental health outcomes during menopause: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Behav Med. 2007;33:132–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Joshi S, Khandwe R, Bapat D, Deshmukh U. Effect of yoga on menopausal symptoms. Menopause Int. 2011;17:78–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carson JW, Carson KM, Porter LS, Keefe FJ, Seewaldt VL. Yoga of Awareness program for menopausal symptoms in breast cancer survivors: results from a randomized trial. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17:1301–1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ngowsiri K, Tanmahasamut P, Sukonthasab S. Rusie Dutton traditional Thai exercise promotes health related physical fitness and quality of life in menopausal women. Complement Ther Clin Pract 2014;20:164–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Newton KM, Reed SD, Guthrie KA, et al. Efficacy of yoga for vasomotor symptoms: a randomized controlled trial. Menopause. 2014;21:339–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Carpenter JS, Woods NF, Otte JL, et al. MsFLASH participants’ priorities for alleviating menopausal symptoms. Climacteric. 2015:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kinser PA, Robins JL. Control group design: enhancing rigor in research of mind-body therapies for depression. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2013;2013:140467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McCambridge J, Sorhaindo A, Quirk A, Nanchahal K. Patient preferences and performance bias in a weight loss trial with a usual care arm. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;95:243–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jorge MP, Santaella DF, Pontes IM, et al. Hatha Yoga practice decreases menopause symptoms and improves quality of life: a randomized controlled trial. Complement Ther Med. 2016;26:128–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Berg JA, Taylor D, Woods NF. Women’s Health Expert Panel of the American Academy of N: Where we are today: prioritizing women’s health services and health policy. A report by the Women’s Health Expert Panel of the American Academy of Nursing. Nurs Outlook. 2013;61:5–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Menopause: diagnosis and management. NICE Guidelines [NG23]. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng23. (Accessed April 27, 2016). [PubMed]

- 56.Grant MD, Marbella A, Wang AT, et al. Menopausal Symptoms: Comparative Effectiveness of Therapies. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 147 (Prepared by Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association Technology Evaluation Center Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. 290–2007-10058-I.) AHRQ Publication No. 15-EHC005-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; March 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tsai SA, Stefanick ML, Stafford RS. Trends in menopausal hormone therapy use of US office-based physicians, 2000–2009. Menopause. 2011;18:385–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pagan JA, Pauly MV. Complementary and alternative medicine: personal preference or low cost option? LDI Issue Brief. 2004;10:1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pagan JA, Pauly MV. Access to conventional medical care and the use of complementary and alternative medicine. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24:255–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen KM, Chen MH, Chao HC, Hung HM, Lin HS, Li CH. Sleep quality, depression state, and health status of older adults after silver yoga exercises: cluster randomized trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46:154–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Patel NK, Newstead AH, Ferrer RL. The effects of yoga on physical functioning and health related quality of life in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Altern Complement Med. 2012;18:902–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Park CL, Braun T, Siegel T. Who practices yoga? A systematic review of demographic, health-related, and psychosocial factors associated with yoga practice. J Behav Med. 2015;38:460–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry: Estrogen and Estrogen/Progestin Drug Products to Treat Vasomotor Symptoms and Vulvar and Vaginal Atrophy Symptoms—Recommendations for Clinical Evaluation. (Draft guidance from the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), January 2003). Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DrugSafety/InformationbyDrugClass/UCM135338.pdf. (Accessed January 27, 2016).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.