Summary

Fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) is a marker of airway inflammation that is well-characterized in allergic disease states. However, FeNO is also involved in non-allergic inflammatory and pulmonary vascular mechanisms or responses to environmental stimuli. We sought to determine the extent to which obesity or sedentary lifestyle is associated with FeNO in adolescents not selected on the basis of allergic disease. In Project Viva, a pre-birth cohort study, we measured body mass index (BMI), skinfold thicknesses, waist circumference, body fat, hours watching television, hours of physical activity, and heart rate after exercise among 929 adolescents (median age 12.9). We measured FeNO twice and averaged these as a continuous, log-transformed outcome. We performed linear regression models, adjusted for child age, sex, height, and race/ethnicity, maternal education and smoking during pregnancy, household income and smoking, and neighborhood characteristics. In secondary analysis, we additionally adjusted for asthma. More than two hours spent watching TV was associated with 10% lower FeNO (95% CI: −20, 0%). Higher body fat percentage was also associated with lower FeNO. After additional adjustment for asthma, teens who are underweight (BMI <5th %tile, 3%) had 22% lower FeNO (95% CI: −40, 2%) and teens who are overweight (BMI ≥85th %ile, 28%) had 13% lower FeNO (95% CI: −23, −2%). Each of these associations of lifestyle and body weight with lower FeNO were greater in magnitude after adjusting for asthma. In summary, sedentary lifestyle, high and low BMI were all associated with lower FeNO in this adolescent cohort.

Keywords: teenagers, inflammation, asthma, overweight

Introduction

Obesity is a worldwide epidemic that affects 1 in 5 of the children and adolescents in the United States.1 Obesity is associated with several comorbid conditions, in large part due to its pro-inflammatory nature. The systemic inflammation in obesity is marked by increases in pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, CRP, and TNFα that stimulate a cascade of events including the production of acute phase proteins as well as the induction of nitric oxide synthase.2–5 Obesity has also been associated with specific immune effects. For example, obesity-associated insulin resistance has been associated with Th1 polarization, while obesity-associated dyslipidemia has been shown to increase monocyte activation.4,6 These pro-inflammatory and immune effects noted in obesity offer possible explanations for the comorbid conditions seen in obesity, including diabetes, and steatohepatitis. Specifically in the lung, obesity-associated inflammation has been linked to the development of asthma, ARDS, and pulmonary vascular disease.4 In this study, we explore whether obesity is associated with levels of exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO), a marker of airway inflammation.

NO is an intercellular messenger known to mediate a variety of processes, including immune function, inflammation, and vascular tone.7,8 NO in exhaled air (FeNO) has been well-studied in allergic inflammatory airway states including asthma and allergic rhinitis, in which FeNO is elevated.9 Current American Thoracic Society (ATS) guidelines recommend the use of FeNO to diagnose eosinophilic airway inflammation, predict steroid responsiveness, and support a diagnosis of asthma when there is a need for further objective data in uncertain cases.9

While well characterized in allergic disease including allergic asthma, the study of FeNO is evolving in other inflammatory disease states, including obesity. Presently, ATS guidelines recommend considering alternative diagnoses in individuals with symptoms of asthma but low FeNO, including obesity.9 However, it is unknown specifically how obesity and FeNO relate. In children with a family history of atopy, sedentary lifestyles, including watching TV, have been associated with increased FeNO independently of BMI and allergic sensitization.10 Others have found elevated FeNO in people with non-atopic chronic conditions including diabetes and COPD exposed to higher levels of air pollution,11 and in non-atopic pulmonary conditions including ILD, bronchiectasis, and COPD12–14 On the other hand, FeNO is consistently lower among tobacco and marijuana smokers, an effect attributed to pulmonary vasoconstrictive effects of these noxious exposures.15 Studies of asthmatic children and adults have found lower FeNO among asthmatics with obesity, but the association of obesity and FeNO in non-asthmatic children is not well-described.16,17

Exhaled NO is therefore a marker of allergic airway inflammation that is variably affected by non-allergic inflammatory and vascular mechanisms. Given the increasing prevalence of obesity in children and adolescents and its associated comorbid conditions, we sought to evaluate the relationship between BMI and lifestyle with FeNO in a large population of adolescents not enriched for asthma or atopy.

Materials and Methods

Study population

Between 1999 and 2002, we recruited women in early pregnancy into Project Viva from eight obstetric offices of Atrius Harvard Vanguard Medical Associates, a multi-specialty group practice in eastern Massachusetts. Exclusion criteria included multiple gestation, inability to answer questions in English, and gestational age ≥22 weeks at recruitment. Details of recruitment and retention are available elsewhere.18 Of the 2,128 infants, we included 929 participants with FeNO measurements at an in-person visit in early adolescence. Compared with the 929 included participants, the 1,199 excluded participants showed a lower proportion of maternal college education (59% versus 71%) and higher smoking rates during pregnancy (15% versus 9%) but did not differ on child sex or race/ethnicity.

We performed in-person study visits with the mother during pregnancy, and with both mother and child immediately after delivery and during infancy, early childhood, mid-childhood, and the early teens. Mothers provided written informed consent at each visit, and teens provided assent at the early teen visit. Institutional review boards of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care approved the study (IRBNet# 228471).

Exposures and questionnaire data

At the early teen visit, we measured children’s height using calibrated stadiometers (Shorr Productions, Olney, MD), and weight with calibrated Tanita scales. We calculated BMI in kilograms per meters squared (kg/m2) and age- and sex-specific BMI z-scores using CDC 2000 reference data.19 We defined underweight as <5th percentile and overweight or obesity as ≥85th percentile, with normal weight (5th to <85th percentile) as the comparison.25,19 We measured waist circumference (cm) using Lefkin woven tape. We measured subscapular and triceps skinfold thicknesses (mm) using Holtain calipers (Holtain LTD, Crosswell, United Kingdom). We measured total body fat using dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) and by bioimpedance (BIA), which was measured by foot-foot bioimpedance (Tanita scale model TBF-200A, Tanita Corporation of America, Arlington Heights, IL).20

We measured sedentary lifestyle by estimated hours spent watching TV, videos, or DVDs reported on parental questionnaire during early teen visit. From a continuous number of hours (h) per day reported, we derived a dichotomous variable for analysis, with ≥2h defined as high and <2 as low, based on previous studies showing increased rates of obesity in children for those watching ≥2h of television per day.21 Activity levels were defined based on parental questionnaire responses at early teen visit regarding the number of hours spent in vigorous activity per week. From a continuous number of hours reported, we derived a dichotomous variable for analysis, with low (<7h) versus high (≥7h), based on World Health Organization recommendation of 60 minutes per day of vigorous activity for this age group.22 In addition, participants completed a step test to assess physical fitness; we examined heart rate 2 minutes after the test, reported in sex-specific quartiles with a 3-category exposure (Q1, Q2–3 (reference), and Q4).

We defined ‘current asthma’ as a maternal report of ever asthma doctor diagnosis plus wheeze symptoms in the past 12 months or use of asthma medication in the past month, reported on the early teen questionnaire. We used as the comparison those with no asthma diagnosis, no wheeze, and no asthma medications. In other words, if ever asthma but not current asthma, we set current asthma to missing (excluded). Questions were drawn from the validated International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) questionnaire.23,24

Outcome: exhaled NO

Exhaled NO levels were measured with a portable electrochemical device (NIOX MINO; Aerocrine AB); this has been validated by chemiluminescence technology, with an accuracy of ± 5 parts per billion (ppb).25 Prior to measurements, subjects breathed in through an NO-scrubbing filter and exhaled into room air twice. On the third breath, subjects inhaled through the filter and exhaled into the analyzer. The last three seconds of the exhalation was utilized for FeNO measurement; this ensures lower rather than upper airway measurement. Nose clips were not used. This procedure was performed twice. Measurements of FeNO were made prior to exercise step testing.

Statistical analysis

We assigned the average of two consecutive FeNO measurements to each participant. Due to non-normality, we examined FeNO as a continuous, log-transformed outcome. We performed linear regression analyses of each measure of adiposity and sedentary lifestyle with log-transformed average FeNO as the outcome. We adjusted the parsimonious models for child age, sex, and height at the early teen visit. Fully adjusted models were additionally adjusted for child race/ethnicity, maternal education and smoking during pregnancy, household income and smoking in the home at the time of visit, and median value of census tract owner-occupied housing and percent of home census tract with a bachelor’s degree or higher (based on home address at the mid-childhood visit and using year 2000 census tract data). These potential confounders were selected a priori, based on known or suspected associations with obesity or risk of asthma or allergy. In secondary analysis, we additionally adjusted for current asthma as a potential mediator to see if the associations of obesity or sedentary lifestyle with FeNO persisted after adjustment for asthma.

We ran several secondary analyses on our data. Based on previous studies16,17 that have found that obesity affects FeNO only in atopic or asthma subjects and not their healthy peers, we tested if the association of BMI category with FeNO differed by current asthma status by adding and interaction term for current asthma by BMI category to our models. Since recent steroid use may affect FeNO levels9 we performed a sensitivity analysis excluding the 22 participants who had used inhaled corticosteroids in the past 72 hours. No participants had used oral steroids within 72 hours. We also ran fully adjusted models to confirm well-known associations of asthma with FeNO and of obesity with odds of asthma in this population.

Results

Study population

The characteristics of the study participants are shown in Table 1. Seventy-one percent of mothers had a college degree or higher and average household income at initial visit was $109,000. Household smoking was rare, occurring in 12% of participants’ households at their early teen visit. Participants were predominantly white (64%) with mean age 13 years. Most (68%) had BMI within normal range (5-<85th percentile). Two-thirds (65%) watched ≥2h of TV or videos per day, and most (77%) participated in less than 7h of vigorous physical activity per week. Mean (SD) FeNO was 26 (27) ppb, which is within normal range for this age group.9 Current asthma was reported in 14% of participants.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics, overall and according to child sex (n=929)

| Overall | Girls | Boys | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n=929 | n=463 | n=466 | |

| Mean (SD) or N (%) | |||

| Child at early teen visit | |||

| Race/ethnicity, % | |||

| . Black | 154 (17) | 74 (16) | 80 (17) |

| . Hispanic | 40 (4) | 20 (4) | 20 (4) |

| . Asian | 28 (3) | 13 (3) | 15 (3) |

| . White | 593 (64) | 301 (65) | 292 (63) |

| . Other | 113 (12) | 54 (12) | 59 (13) |

| Age, years | 13 (1) | 13 (1) | 13 (1) |

| Height, cm | 160 (9) | 159 (8) | 161 (10) |

| BMI percentile category, % | |||

| . <5th | 30 (3) | 16 (3) | 14 (3) |

| . 5-<85th | 634 (68) | 316 (68) | 318 (69) |

| . ≥85th | 262 (28) | 130 (28) | 132 (28) |

| Waist circumference, cm | 73 (12) | 73 (11) | 74 (12) |

| SS+TR skinfold thickness, mm | 29 (14) | 31 (14) | 27 (14) |

| BIA body fat % | 22 (10) | 26 (10) | 18 (9) |

| DXA body fat % | 29 (8) | 30 (7) | 27 (8) |

| Exhaled Nitric Oxide, ppb | 26 (27) | 24 (26) | 28 (28) |

| Current asthma, % | 115 (14) | 59 (14) | 56 (14) |

| TV or videos, ≥2 h/d, % | 589 (65) | 283 (63) | 306 (68) |

| Vigorous physical activity <7 h/w, % | 705 (77) | 358 (78) | 347 (76) |

| HR after step test 2 minutes, beats/min | 86 (18) | 90 (19) | 82 (17) |

|

Mother/family | |||

| Mother ≥college graduate at enrollment, % | 662 (71) | 336 (73) | 326 (70) |

| Annual household income at visit, $1000s | 109 (44) | 110 (44) | 109 (44) |

| Maternal smoking status during pregnancy, % | |||

| . Never | 653 (71) | 326 (71) | 327 (70) |

| . Former | 188 (20) | 93 (20) | 95 (20) |

| . Current (during pregnancy) | 85 (9) | 41 (9) | 44 (9) |

| Any smokers at home at time of visit, % | 114 (12) | 52 (11) | 62 (13) |

| Percent ≥bachelors (census tract, mid-childhood) | 42 (20) | 42 (20) | 42 (20) |

| Median value owner-occupied housing (census tract, mid-childhood), $1000s | 264 (149) | 263 (147) | 264 (150) |

Lifestyle and exhaled nitric oxide

Associations of lifestyle and fitness with FeNO are shown in Table 2. Sedentary lifestyle, defined as ≥2 h/day watching TV or videos, was associated with a 10% lower FeNO (95% CI: −20, 0%) (model 2) and with 12% lower FeNO (95% CI: −21, −2%) after adjustment for asthma (model 3). Low vigorous physical activity (<7 h/week) and physical fitness (determined by heart rate after step test) were not associated with FeNO.

Table 2.

Associations of lifestyle, fitness, and body composition with FeNO in early adolescence

| % difference (95% CI) in FeNO | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | (n) | Model 2 | (n) | Model 3 | (n) | |

| TV or videos, ≥2 h/d (yes v. no) | −7 (−16, 3) | 901 | −10 (−20, 0) | 779 | −12 (−21, −2) | 665 |

| Vigorous physical activity <7 h/w (yes v. no) | 0 (−11, 11) | 912 | −1 (−13, 11) | 791 | −3 (−14, 10) | 677 |

| HR after step test 2 minutes (quartiles) | 897 | 780 | 670 | |||

| . Q1 | −2 (−12, 10) | −4 (−15, 9) | −2 (−13, 12) | |||

| . Q2-Q3 | 0 (ref) | 0 (ref) | 0 (ref) | |||

| . Q4 | 3 (−8, 16) | 5 (−7, 19) | 8 (−5, 23) | |||

| BIA* body fat % (per IQR=15.6) | 3 (−5, 11) | 917 | 0 (−9, 9) | 791 | −4 (−13, 5) | 676 |

| Waist circumference (per IQR=13 cm) | −1 (−6, 5) | 925 | −3 (−9, 4) | 798 | −5 (−11, 1) | 683 |

| SS+TR‡ skinfold thickness (per IQR=17 mm) | −1 (−6, 5) | 923 | −3 (−9, 4) | 795 | −6 (−12, 0) | 680 |

| DXA† body fat % (per IQR=10.6 %) | −4 (−12, 4) | 709 | −5 (−13, 4) | 643 | −9 (−17, −1) | 545 |

| BMI percentile category, % | 926 | 798 | 683 | |||

| . <5th | −26 (−43, −4) | −24 (−43, 1) | −22 (−40, 2) | |||

| . 5-<85th | 0 (ref) | 0 (ref) | 0 (ref) | |||

| . ≥85th | −5 (−14, 5) | −8 (−19, 3) | −13 (−23, −2) | |||

Model 1. Adjusted for child age, sex, and height at the early teen visit.

Model 2. Model 1 additionally adjusted for child race/ethnicity; maternal education and smoking during pregnancy; household income and smoking in the home at time of visit; and home address year 2000 census tract median value of owner-occupied housing and education

Model 3. Model 2 additionally adjusted for current asthma.

% change (95% CI): (exponentiated (β) - 1) * 100

BIA: bioelectrical impedance analysis

SS + TR: subscapular and triceps

DXA: Dual Energy X-ray Absorptiometry

Body composition and exhaled nitric oxide

Associations of BMI and body composition with FeNO are shown in Table 2. Low BMI (<5th percentile) was associated with a 24% lower FeNO (95% CI: −43, 1%) compared to the reference category of 5th-<85th percentile. High BMI (≥85th percentile) was also associated with lower FeNO only after additional adjustment for current asthma (−13% lower FeNO; 95% CI: −23, −2%) compared to teens with normal BMI (Table 2). Higher percent body fat by DXA was associated with 5% lower FeNO (95% CI: −13, 4%) per 10.6% increment in body fat, which is the interquartile range (IQR) difference in percent body fat in the study population. After adjusting for current asthma, the association between higher body fat and lower FeNO nearly doubled in magnitude and was statistically significant: 9% lower FeNO (95% CI: −17, −1%) per IQR difference in percent body fat. Waist circumference and skinfold thickness were not associated with FeNO (Table 2).

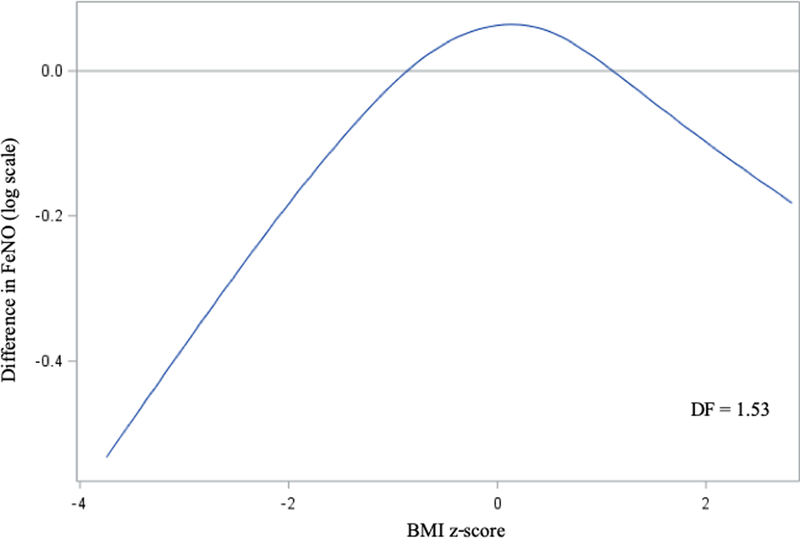

As a post-hoc analysis, we evaluated the linearity of the association of continuous age-and sex-specific between BMI z-score with FeNO by plotting a B-spline using a generalized additive model (GAM) with a smoothing parameter for BMI z-score. We allowed the degrees of freedom to be selected by the generalized cross validation method. A plot of the spline is shown in Figure 1. The Chi-square value of the test for linearity confirmed departure from linearity (p=0.0006).

Figure 1: Adjusted of BMI z-score with FeNO in early adolescence.

Generalized additive model with smoothing function (B-spline) for BMI, adjusted for child age, sex, height and race/ethnicity; maternal education and smoking during pregnancy; household income and smoking in the home at time of visit; year 2000 census tract median value of owner-occupied housing and education; and current asthma.

In sensitivity analyses, we found no statistical evidence that the association of BMI category with FeNO differed among those with and without current asthma (p-value for interaction = 0.32). Associations of sedentary lifestyle and BMI with FeNO were similar after excluding 112 participants with current asthma, and 22 participants with recent inhaled steroid use (Table E1, online supplement), although the magnitude of the negative association of low BMI with FeNO was attenuated after excluding those with current asthma.

As expected, current asthma was associated with higher average FeNO: 97% higher compared to teens with no asthma (95% CI 70%, 128%) in models adjusted for age, sex, height, ethnicity; maternal education and smoking during pregnancy; household income and smoking in the home at time of visit; and home address year 2000 census tract median value of owner-occupied housing and education. Moreover, in logistic regression models, high BMI (≥85th percentile) was associated with slightly higher odds of current asthma (odds ratio 1.2, 95% CI 0.8, 2.0), while low BMI was not associated with odds of asthma (odds ratio 0.9, 95% CI 0.3, 3.3) (model 2).

Discussion

We investigated the relationship between obesity and FeNO, a marker of allergic airway inflammation, in an adolescent population. We found that after accounting for current asthma, low BMI was associated with a 22% lower FeNO and high BMI was associated with a 13% lower FeNO compared to normal weight children. These are small differences in FeNO that generally fall within the normal range of FeNO. This association persisted after adjustment for current asthma, which is well-known to be associated with elevated FeNO.9 Similarly, higher percentage body fat by DXA and sedentary lifestyle, defined as watching over 2 hours of TV daily, were both associated with lower FeNO, with more pronounced associations after adjusting for current asthma. Below, we discuss several possible explanations for our finding of lower FeNO among adolescents with obesity, including an increase in asymmetric dimethyl arginine (ADMA) relative to L-arginine, effect of weight on airway size and pulmonary mechanics, and vascular factors.

First, in obesity, there may be an increase in the concentration of ADMA relative to L-arginine, leading to reduction in FeNO. In a study of adult asthmatics, Holguin, et al. found an inverse correlation between BMI and the ratio of L-arginine/ADMA in subjects with late-onset asthma. Those individuals with late-onset asthma also were noted to have an inverse relationship between BMI and FeNO, and this relationship was lost after adjusting for L-arginine/ADMA suggesting potential mediation of the association with FeNO by L-arginine/ADMA.26 Therefore, the relationship between L-arginine and ADMA may play an important role in the negative association between BMI and FeNO. Both ADMA and L-arginine are involved in the production of NO through their ability to inhibit nitric oxide synthase (NOS). ADMA is a product of posttranslational methylation of L-arginine, and it can compete with L-arginine to inhibit nitric oxide synthesis. By competing with L-arginine, ADMA uncouples all NOS isoforms, effectively shifting NOS from producing NO to making superoxide and leading to the formation of nitrogen oxide radicals.27 Obesity has been shown to be associated with higher plasma ADMA.28 Individuals with obesity, therefore, may have lower L-arginine/ADMA, resulting in greater uncoupling of NOS and therefore lower FeNO.

Another explanation for the observed relationship in this study between weight and FeNO involves the effects of body size on lung mechanics. In a large cohort of children and adolescents, Yao and colleagues found that FeNO was negatively associated with BMI, which may be explained in part by more narrow airways observed those with higher BMI.29,30 If the exhalation rate at the mouth is kept constant as in FeNO collection, those with narrow airways may have an increase in airflow velocity, decreasing the transit time of alveolar gas in the airway and reducing the amount of nitric oxide exhaled.29,31

The impact of airway size, however, would not explain the low FeNO observed in underweight study participants. One explanation for the low FeNO in this group may instead be explained by nutritional status. In their analysis of BMI and FeNO in NHANES, Uppalapati and colleagues found that low BMI was associated with lower FeNO in an adult population. One explanation is that those with poor nutritional status may have low arginine levels, which is required for NO production.32 Furthermore, malnourished individuals may have low thiamine levels, which can affect NO production through modulation of nitric oxide synthase.33

Finally, the relationship between obesity and FeNO may be explained by vascular factors. Exhaled NO is influenced by a number of processes at the cellular level, not only allergic inflammation, and can be low in other disease states including pulmonary hypertension.34 NO is known to have vasodilatory properties via stimulation of calcium-dependent endothelial nitric oxide synthase (FeNOS), which releases NO. NO causes smooth muscle cells to relax either directly or indirectly by its effect on calcium.35 Cigarette smoking is associated with low FeNO, which has been attributed to the vasoconstrictive effect of tobacco exposure.15,36,37 Similarly, inhaled marijuana has been associated with lower FeNO.38 It is possible that effects of obesity and/or underweight result in changes in the pulmonary vasculature that lower FeNO.

We acknowledge study limitations. Most importantly, study participants were predominantly white and from educated families residing in the Boston area. This may limit generalizability to other groups that have greater burdens and severity of childhood obesity, sedentary lifestyle and poor nutrition. Our evaluation of sedentary lifestyle (physical activity, hours of TV/video) was based on questionnaire data that may be imprecise and subject to recall bias. Our study also has several strengths. We examined FeNO according to American Thoracic Society standards, among a large cohort of adolescents, which is an age group that is under-represented in the medical literature. The pre-birth nature of the cohort allowed for adjustment of potential confounders ascertained during pregnancy. In addition, we controlled for differences in socioeconomic status at the level of the individual, household, and census tract. Our study is also novel in that we examined adolescent lifestyle factors, such as time watching TV or spent in physical activity, physical fitness, and multiple markers of obesity to differentiate physiological effects of body weight, composition and sedentary behavior on FeNO.

In summary, we found that high and low BMI were each associated with lower FeNO, with and without controlling for asthma. Because of these associations with lower FeNO, body weight may be an important factor to consider in the interpretation of FeNO.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the US National Institutes of Health (K23ES026204, R01 HD034568, R01AI102960, UH3OD023286), the American Thoracic Society Foundation and the American Lung Association.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: none

References

- 1.Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of Obesity Among Adults and Youth: United States, 2015–2016. NCHS data brief. 2017;(288):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomas PS. Tumour necrosis factor-alpha: The role of this multifunctional cytokine in asthma. Immunology and Cell Biology. 2001;79(2):132–140. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2001.00980.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shore SA. Obesity and asthma: Possible mechanisms. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2008;121(5):1087–1093. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suratt BT, Ubags NDJ, Rastogi D, Tantisira KG, Marsland BJ, Petrache I, Allen JB, Bates JHT, Holguin F, McCormack MC, et al. An Official American Thoracic Society Workshop Report: Obesity and Metabolism. An Emerging Frontier in Lung Health and Disease. Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 2017;14(6):1050–1059. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201703-263WS [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith U, Andersson CX, Gustafson B, Hammarstedt A, Isakson P, Wallerstedt E. Adipokines, systemic inflammation and inflamed adipose tissue in obesity and insulin resistance. International Congress Series. 2007;1303:31–34. doi: 10.1016/J.ICS.2007.03.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rastogi D, Fraser S, Oh J, Huber AM, Schulman Y, Bhagtani RH, Khan ZS, Tesfa L, Hall CB, Macian F. Inflammation, Metabolic Dysregulation, and Pulmonary Function among Obese Urban Adolescents with Asthma. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2015;191(2):149–160. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201409-1587OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bogdan C. Nitric oxide and the immune response. Nature Immunology. 2001;2(10):907–916. doi: 10.1038/ni1001-907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barnes PJ, Liew FY. Nitric oxide and asthmatic inflammation. Immunology Today. 1995;16(3):128–130. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80128-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dweik RA, Boggs PB, Erzurum SC, Irvin CG, Leigh MW, Lundberg JO, Olin AC, Plummer AL, Taylor DR. An official ATS clinical practice guideline: Interpretation of exhaled nitric oxide levels (FENO) for clinical applications. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2011;184(5):602–615. doi: 10.1164/rccm.9120-11ST [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sordillo JE, Webb T, Kwan D, Kamel J, Hoffman E, Milton DK, Gold DR. Allergen exposure modifies the relation of sensitization to fraction of exhaled nitric oxide levels in children at risk for allergy and asthma. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2011;127(5):1165–1172.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.01.066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peng C, Luttmann-Gibson H, Zanobetti A, Cohen A, De Souza C, Coull BA, Horton ES, Schwartz J, Koutrakis P, Gold DR. Air pollution influences on exhaled nitric oxide among people with type II diabetes. Air Quality, Atmosphere and Health. 2016;9(3):265–273. doi: 10.1007/s11869-015-0336-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kharitonov SA, Barnes PJ. Exhaled markers of inflammation. Current opinion in allergy and clinical immunology. 2001;1(3):217–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kharitonov SA, Wells AU, O’Connor BJ, Cole PJ, Hansell DM, Logan-Sinclair RB, Barnes PJ. Elevated levels of exhaled nitric oxide in bronchiectasis. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1995;151(6):1889–1893. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.151.6.7767536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maziak W, Loukides S, Culpitt S, Sullivan P, Kharitonov SA, Barnes PJ. Exhaled Nitric Oxide in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1998;157(3):998–1002. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.3.97-05009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kharitonov SA, Robbins RA, Yates D, Keatings V, Barnes PJ. Acute and chronic effects of cigarette smoking on exhaled nitric oxide. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1995;152(2):609–612. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.2.7543345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yao TC, Tsai HJ, Chang SW, Chung RH, Hsu JY, Tsai MH, Liao SL, Hua MC, Lai SH, Chen LC, et al. Obesity disproportionately impacts lung volumes, airflow and exhaled nitric oxide in children Chen Y-C, editor. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(4):e0174691. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0174691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Komakula S, Khatri S, Mermis J, Savill S, Haque S, Rojas M, Brown LA, Teague GW, Holguin F. Body mass index is associated with reduced exhaled nitric oxide and higher exhaled 8-isoprostanes in asthmatics. Respiratory Research. 2007;8(1):32. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-8-32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oken E, Baccarelli AA, Gold DR, Kleinman KP, Litonjua AA, Meo D De, Rich-Edwards JW, Rifas-Shiman SL, Sagiv S, Taveras EM, et al. Cohort profile: Project viva. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2015;44(1):37–48. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Growth Charts - Z-score Data Files. 2009. [accessed 2019 Oct 17]. https://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/zscore.htm

- 20.Boeke CE, Oken E, Kleinman KP, Rifas-Shiman SL, Taveras EM, Gillman MW. Correlations among adiposity measures in school-aged children. BMC Pediatrics. 2013;13(1):99. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-13-99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gortmaker SL, Must A, Sobol AM, Peterson K, Colditz GA, Dietz WH. Television viewing as a cause of increasing obesity among children in the United States, 1986–1990. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 1996;150(4):356–362. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1996.02170290022003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organization. Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Global recommendations on physical activity for health. In: World Health Organization; 2010. p. 58. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Asher MI, Keil U, Anderson HR, Beasley R, Crane J, Martinez F, Mitchell EA, Pearce N, Sibbald B, Stewart AW, et al. International study of asthma and allergies in childhood (ISAAC): rationale and methods. European Respiratory Journal. 1995;8(3):483–491. doi: 10.1183/09031936.95.08030483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jenkins MA, Clarke JR, Carlin JB, Robertson CF, Hopper JL, Dalton MF, Holst DP, Choi K, Giles GG. Validation of questionnaire and bronchial hyperresponsiveness against respiratory physician assessment in the diagnosis of asthma. International Journal of Epidemiology. 1996;25(3):609–616. doi: 10.1093/ije/25.3.609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khalili B, Boggs PB, Bahna SL. Reliability of a new hand-held device for the measurement of exhaled nitric oxide. Allergy. 2007;62(10):1171–1174. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01475.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holguin F, Comhair SAA, Hazen SL, Powers RW, Khatri SS, Bleecker ER, Busse WW, Calhoun WJ, Castro M, Fitzpatrick AM, et al. An Association between l -Arginine/Asymmetric Dimethyl Arginine Balance, Obesity, and the Age of Asthma Onset Phenotype. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2013;187(2):153–159. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201207-1270OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wells SM, Holian A. Asymmetric Dimethylarginine Induces Oxidative and Nitrosative Stress in Murine Lung Epithelial Cells. American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology. 2007;36(5):520–528. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0302SM [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McLaughlin T, Stühlinger M, Lamendola C, Abbasi F, Bialek J, Reaven GM, Tsao PS. Plasma Asymmetric Dimethylarginine Concentrations Are Elevated in Obese Insulin-Resistant Women and Fall with Weight Loss. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2006;91(5):1896–1900. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yao T-C, Ou L-S, Lee W-I, Yeh K-W, Chen L-C, Huang J-L. Exhaled nitric oxide discriminates children with and without allergic sensitization in a population-based study. Clinical & Experimental Allergy. 2011;41(4):556–564. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2010.03687.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.King GG, Brown NJ, Diba C, Thorpe CW, Muñoz P, Marks GB, Toelle B, Ng K, Berend N, Salome CM. The effects of body weight on airway calibre. European Respiratory Journal. 2005;25(5):896–901. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00104504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ho LP, Wood FT, Robson A, Innes JA, Greening AP. The current single exhalation method of measuring exhales nitric oxide is affected by airway calibre. The European Respiratory Journal. 2000;15(6):1009–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uppalapati A, Gogineni S, Espiritu JR. Association between Body Mass Index (BMI) and fraction of exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) levels in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2007–2010. Obesity Research & Clinical Practice. 2016;10(6):652–658. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2015.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gioda CR, Capettini LSA, Cruz JS, Lemos VS. Thiamine deficiency leads to reduced nitric oxide production and vascular dysfunction in rats. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases. 2014;24(2):183–188. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2013.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaneko FT, Arroliga AC, Dweik RA, Comhair SA, Laskowski D, Oppedisano R, Thomassen MJ, Erzurum SC. Biochemical reaction products of nitric oxide as quantitative markers of primary pulmonary hypertension. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1998;158(3):917–923. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.3.9802066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van Hove CE, Van Der Donckt C, Herman AG, Bult H, Fransen P. Vasodilator efficacy of nitric oxide depends on mechanisms of intracellular calcium mobilization in mouse aortic smooth muscle cells. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2009;158(3):920–930. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00396.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Michils A, Louis R, Peche R, Baldassarre S, Van Muylem A. Exhaled nitric oxide as a marker of asthma control in smoking patients. European Respiratory Journal. 2009;33(6):1295–1301. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00154008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dressel H, de la Motte D, Reichert J, Ochmann U, Petru R, Angerer P, Holz O, Nowak D, Jörres RA. Exhaled nitric oxide: Independent effects of atopy, smoking, respiratory tract infection, gender and height. Respiratory Medicine. 2008;102(7):962–969. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Papatheodorou SI, Buettner H, Rice MB, Mittleman MA. Recent Marijuana Use and Associations With Exhaled Nitric Oxide and Pulmonary Function in Adults in the United States. Chest. 2016;149(6):1428–35. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2015.12.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.