Introduction

Although Parkinson’s disease (PD) was first described by James Parkinson over 200 years ago [1], the underlying clinical variability of this complex syndrome remains difficult to delineate. A thorough understanding of this heterogeneity is critical for diagnosis, prognosis, treatment, clinical trial endpoints, and pathophysiological insight [2–7]. It is now recognized that PD motor phenotypes may change during the course of disease[8–10], and since these phenotypes are associated with comorbidities[11,12], there is interest in identifying and intervening in the factors that contribute to this process[13]. However, organizing this phenotypic distribution into reproducible and quantifiable subtype categories is a prerequisite and an unsettled area of ongoing research, particularly because there is a wide variety of data (e.g., scales and questionnaires) that can be used as input to a wide variety of clustering techniques [14,15]. Subtyping approaches aim to accurately characterize the most common phenotype clusters and provide an efficient mechanism for selecting the best-fit subtype for any PD individual at any particular time [14]. Unfortunately, a widely agreeable system for subtype classification and assignment is currently lacking.

To overcome these difficulties, the last decade has observed increasing use of data-driven and systematic approaches for motor and non-motor subtyping [14]. While novel, these techniques may suffer from cross-sectional study design or limited follow-up, small sample size, and lack of reproducibility across different PD samples. Large datasets with long-term follow-up are needed to ensure representative data that span the full spectrum of PD symptom heterogeneity. Despite vast differences in subtyping categories seen throughout the literature [16–19], an emerging consensus is the subtype designations for tremor dominant (TD) patients and postural instability and gait disorder/dominance (PIGD) as defined by motor assessment [8,16]. In this schema, individuals not fitting criteria for TD or PIGD are placed into an intermediate/indeterminate type (IT) category.

In a recent study, we used hierarchical correlational clustering of Parkinson’s Progression Marker’s Initiative (PPMI)[20] motor scores to objectively recapitulate these TD, IT, and PIGD subtypes which were originally defined through clinical observation [8]. With respect to subtype designations and disease duration, we noted a slow shift away from TD and towards PIGD subtypes in about half of the patients within the first 5 years of diagnosis. In this study, our goal was to validate this clustering-based subtyping routine in a larger PD sample and extend follow-up to 20 years after diagnosis.

Materials and methods

We used the institutional review board (IRB)-approved University of Florida (UF) INFORM database of PD patients, who previously provided informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. UF-INFORM is a clinical-research database that provides information on demographics, clinical, and functional characteristics of patients with movement disorders. Inclusion criteria were individuals diagnosed with idiopathic PD by a movement disorders-trained neurologist with a documented estimated date of symptom onset. Exclusion criteria were patients who received deep brain stimulation therapy and patients that eventually received a different diagnosis. We compiled together scores from all items of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) Part III and items 13, 14, 15, and 16 from Part II within 20 years after disease onset[16]. To specifically study the natural disease process, we only considered off-medication (med) scores. Patients were required to have at least one recorded Part III assessment on the same date as a Part II assessment. 2,195 PD patients met inclusion and exclusion criteria, comprising a total 5,278 off-med motor score time points. Methods followed closely from prior work that utilized a different dataset [8]. Briefly, we used hierarchical correlational clustering [21] of motor scores to identify subtype categories using data from all time points. We also repeated the subtyping procedure with data from only the first 4 years after symptom onset. Subtype subscores were computed at each time point for each patient and individuals were assigned the appropriate subtype. Subtypes were assigned using ratios of subscores (mean score of UPDRS items within a subtype category) and previously established cutoff criteria[16] (see Methods of [8]. Data were binned in 2-year increments for analysis at the group level.

Next, we determined whether individuals fit criteria for stable (consistent) or unstable (inconsistent) subtyping during follow-up. For individuals with multiple different subtypes during follow-up, we computed the 25th percentile of the mean duration of time until a subtype change occurred. For individuals with a single subtype throughout follow-up, this value was used to define the minimum length of time needed between the first and last recorded time point to define the subset exhibiting a stable subtype. We analyzed mean proportions of different subtype categories over time, as well as TD and PIGD subscores. We used chi-square and linear regression with significance levels set at 0.05 using R (www.cran.r-project.org).

Results

Data-driven UPDRS-based subtype classifications were compatible with previous movement disorders society (MDS)-UPDRS-based definitions (Table 1). That is, the following groups emerged: TD, PIGD, and IT. Within IT, three groups were named according to their included UPDRS items: bulbar dominant (BD), appendicular dominant (AD), and rigidity dominant (RD). Categories and their respective UPDRS items resulting from the clustering routine were identical when considering all time points (20 years follow up) as when only considering the time points occurring within 4 years of diagnosis.

Table 1.

UPDRS Motor Subtypes

| Subtype Name | UPDRS Itemsa | |

|---|---|---|

| Tremor Dominant (TD) | 2.16, 3.20 (Head, RUE, LUE, RLE, LLE), 3.21 (RUE, LUE) | |

| Intermediate Type (IT) | ||

| Bulbar Dominant (BD) | 3.18, 3.19 | |

| Appendicular Dominant (AD) | 3.23 (R, L), 3.24 (R, L), 3.25 (R, L), 3.26 (R, L), 3.31 | |

| Rigidity Dominant (RD) | 3.22 (Neck, RUE, LUE, RLE, LLE) | |

| Postural Instability and Gait Disorder (PIGD) | 2.13, 2.14, 2.15, 3.27, 3.28, 3.29, 3.30 | |

R: Right, L: Left, UE: Upper Extremity, LE: Lower Extremity

The first column lists the names we assigned to the clusters consisting of the UPDRS items included in the second column. BD, AD, and RD are collectively classified as IT.

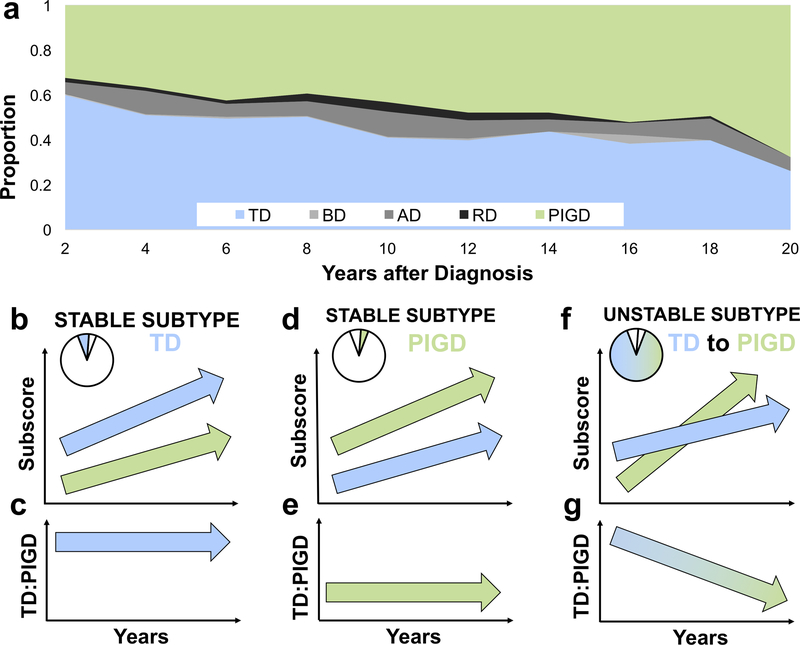

The year of symptom onset was available for 1680 individuals (76.5%). The first bin (0–2 years) had 542 data points whereas the final bin (18–20 years) had 65 data points. The drop-off in the number of time points included in each bin over time fell exponentially (slope (β)=−0.37, Intercept (Int)=6.2, R2=0.9, p<10−8). For people with unstable subtypes, relative frequencies between 0–2 years after diagnosis (542 time points) were 50.5% TD, 0.19% BD, 8.3% AD, 2.4% RD, and 38.6% PIGD. By 18–20 years after diagnosis (65 time points), relative frequencies changed to 20.0% TD, 0% BD, 6.2% AD, 0% RD, and 73.8% PIGD. There was a gradual and persistent decrease in the proportion of TD alongside an increase in that of PIGD throughout 20 years of follow-up (X2(36)=141.9, p<10−13) (Fig. 1A).

Fig 1.

TD = tremor dominant; BD = bulbar dominant; AD = appendicular dominant; RD = rigidity dominant; PIGD = postural instability and gait disorder/dominant. Blue represents TD and green represents PIGD. TD:PIGD = ratio of TD to PIGD subscore. (a) Proportion of individuals over time meeting criteria for each motor subtype. (b-g) In the lower panel, the first row represents subtype subscores, and the second row represents the value of the TD:PIGD ratio, both with respect to time after diagnosis. Each column shows separate categories. Pie charts show the relative number of patients that fit into the designated category. (b) TD-stable individuals show increasing TD and PIGD scores, (c) leading to stable and high TD:PIGD ratios. (d) PIGD-stable individuals also show increasing TD scores and increasing PIGD scores, however PIGD scores remain higher, (e) leading to a stable but lower TD:PIGD ratios. (f) Due to PIGD scores increasingly relatively faster than TD scores, (g) patients with an unstable subtype tend to shifts from TD to PIGD subtypes over time.

Next, we examined TD and PIGD subscores separately over time using regression analyses. These trends are depicted in Fig. 1B–G. We observed that the 118 (7.0%) TD-stable patients tended to have increasing tremor (β=0.05, P<10−12) and PIGD subscores (β=0.03, p<10−11) during follow-up, with higher mean tremor scores throughout (Int=1.2 and Int=0.4 for TD and PIGD, respectively) (Fig. 1B). The computed ratio of TD to PIGD subscores remained stable over time (β=−0.03, Int=4.0, p=0.22) (Fig. 1C). The 78 (4.6%) PIGD-stable patients tended to have increasing tremor (β=0.02, P<10−4) and PIGD subscores (β=0.04, p<10−6) during follow-up, with higher mean PIGD scores throughout (Int=0.4 and Int=1.3 for tremor and PIGD, respectively) (Fig. 1D). Similar to TD-stable patients, for PIGD-stable patients, the computed ratio of tremor to PIGD subscores remained stable over time (β=0.0, Int=0.3, p=0.34) (Fig. 1E). For unstable-subtype patients exhibiting changing phenotypes, the ratio of tremor to PIGD subscores significantly decreased over time (β=−0.06, Int=2.0, p<10−14) (Fig. 1G) due to increasing TD scores (β=0.03, Int=1.0, p<10−15) in the setting of more rapidly increasing PIGD scores (β=0.06, Int=0.7, p<10−15) (Fig. 1F).

Discussion

This study used a large cohort with long-term follow-up to validate and extend preliminary work of a smaller cohort of newly-diagnosed PD patients [8]. We have demonstrated the reproducibility of prior techniques for motor subtyping into TD, IT and PIGD groups based on simple motor assessments[8,22]. Unlike other approaches [18], subtyping that relies on simple and ubiquitous clinical assessments can simplify subtyping procedures and lead to categories with direct clinical interpretation. It is important to note that with this approach, subtype categories - particularly within the IT umbrella - depend on the specific motor assessment used. We have also shown that with this clustering technique, subtype discovery produces the same output categories regardless of the data input being from the first 4 years, or the first 20 years, after symptom onset. Therefore, symptom clustering categories do not depend on disease duration. This suggests that individuals may be subtyped early in disease and subsequently followed during disease progression with meaningful a priori comparison. For example, a patient with a historical TD classification and a newly identified PIGD classification may indicate disease progression. At the individual level, specific trends in subtypes over time may provide helpful clinical information regarding the course of the disease. These findings motivate future studies aiming to prospectively assess the potential prognostic utility of these sample-level trends.

Overall, we found that most patients exhibit changing subtypes with time and that most patients fit TD and PIGD subtype classifications. Consistent with previous work, the relative proportions of IT subtypes remained low and similar throughout disease progression. Clinicians have reported these IT symptoms as being predominant in certain individuals [23,24], and there is little evidence to suggest they be disregarded as distinct phenotypes. However, their utility remains to be determined. For instance, in this sample we recognize the overwhelming paucity of BD assignments, indicating that this group of symptoms may not constitute a representative subtype. These subtypes should be identified and replicated in additional datasets. Focused studies should investigate these IT subtypes to understand the extent to which they truly represent intermediate (i.e., en route to other subtypes) versus indeterminate PD clinical presentations.

Given the predominance of TD and PIGD symptoms in this sample, we analyzed motor subscores to understand these attributes in patients with either stable or unstable PD phenotypes. Interestingly, individuals with either TD-stable or PIGD-stable subtypes continued to show motor severity progression over time as defined by both TD and PIGD subscores. However, they generally increase at similar rates, lending to constant subscore ratios and hence these individuals were assigned a single subtype across multiple time points. For patients with shifting subtypes - representing the vast majority of the cohort - TD predominates early due to initially higher TD subscores and lower PIGD subscores; yet with time, the trajectories intersect and PIGD subscores outpace TD subscores. As a result, there is a slow conversion from higher proportions of TD patients to higher proportions of PIGD patients. Overall, this study reinforces and helps dissect the mechanisms underlying the previously proposed notion that PD subtypes can change over time. In this regard, subtyping routines based only on clinical presentation at diagnosis, expecting a single, perpetual subtype, may result in different subtype designations compared to approaches that consider changes in predominant motor symptoms over time. This is a vital consideration for clinicians and researchers who follow PD patients for many years.

Many questions remain unexplored, such as the impact of medical or surgical treatment on subtype assignment and progression. It is particularly intriguing to note the small proportion of TD-stable individuals who persisted in the TD category at all follow-up assessments. The subjective experience and objective severity of disease in these individuals should be scrutinized to establish whether this group represents a less severe or less progressive form of PD. Similarly, future studies could explore associated factors or therapies that prevent these individuals from transitioning towards PIGD. Indeed, these results may hint at a higher level subtyping schema that classifies individuals into stable-TD, stable-PIGD, or unstable categories. Recently, one study with limited follow-up duration identified three subtyping categories named mild-motor predominant, intermediate, and diffuse malignant[25]. They did not match closely with subtypes used here because most of the TD patients and about half of the PIGD patients in that study were classified as mild-motor predominant, for example. It is possible, however, that with adequate follow-up, the rate or proportion of progression from TD to PIGD could be higher in individuals with the diffuse malignant subtype. Conversely, TD-stable individuals may be more likely to be identified as mild-motor predominant. Overall, the clinical implications of those categories in this context need to be explored.

This study has several limitations. First, although we recognize the importance of non-motor symptoms in PD, we do not consider these symptoms in our subtyping algorithm. Instead our results offer a quantitative framework to define expected motor changes seen with PD progression. Non-motor symptom scales are less ubiquitous and thus purely motor subtyping approaches may have more widespread application to clinical care. Non-motor symptoms in these subtyping groups will be examined in follow-up work. Second, given the retrospective nature of this study, the number of data points at each follow-up dropped markedly over time and this may limit the generalizability of our results. This was, however, the first study to examine these trends up to 20 years after symptom onset. Prospective studies that follow large cohorts at regularly-scheduled visits will provide crucial confirmation to our results. Third, our study utilizes estimated year of symptom onset as opposed to specific dates of diagnosis. Keeping in mind these limitations, our data overall suggests that with disease progression, patients shift toward meeting criteria for the PIGD subtype designation. These results offer a quantitative framework to define expected changes seen during PD progression.

Acknowledgements:

We would like to acknowledge the support of the INFORM database and the Parkinson’s Foundation Center of Excellence located at the University of Florida site.

Funding: This work is supported by a UF Pruitt Family Endowed Faculty Fellowship and by the NIH/NCATS Clinical and Translational Science Awards to the University of Florida UL1TR001427, KL2TR001429, and TL1TR001428.

D.M.R. serves as a consultant for the National Parkinson Foundation and has received honoraria from UCB and the International Parkinson and Movement Disorders Society.

C.W.H. receives grant support from the University of Florida Clinical and Translational Research Institute, which is supported in part by NIH award KL2 TR001429. He has served as a research committee member for the Michael J. Fox Foundation and as a speaker for the National Parkinson Foundation, the Parkinson’s Disease Foundation, and the Davis Phinney Foundation. Dr. Hess has participated in CME and educational activities on movement disorders sponsored by Allergan, Ipsen, Mertz Pharmaceuticals, Peerview Online, and QuantiaMD.

A.R.Z serves as a consultant for the National Parkinson Foundation and has received research consulting honoraria from Medtronic and Bracket.

L.A. has no disclosures to report.

M.S.O. serves as a consultant for the National Parkinson Foundation and has received research grants from NIH, NPF, the Michael J. Fox Foundation, the Parkinson Alliance, Smallwood Foundation, the Bachmann-Strauss Foundation, the Tourette Syndrome Association, and the UF Foundation. M.S.O.’s DBS research is supported by: R01 NR014852. M.S.O. has previously received honoraria, but in the past >60 months has received no support from industry. M.S.O. has received royalties for publications with Demos, Manson, Amazon, Smashwords, Books4Patients, and Cambridge (movement disorders books). M.S.O. is an associate editor for New England Journal of Medicine Journal Watch Neurology. M.S.O. has participated in CME and educational activities on movement disorders (in the last 36) months sponsored by PeerView, Prime, QuantiaMD, WebMD, MedNet, Henry Stewart, and by Vanderbilt University. The institution and not M.S.O. receives grants from Medtronic, AbbVie, Allergan, and ANS/St. Jude, and the Principal Investigator (PI) has no financial interest in these grants. M.S.O. has participated as a site PI and/or Co-Investigator for several NIH, foundation, and industry sponsored trials over the years, but has not received honoraria.

M.S.O. and A.G. receive device donations from Medtronic.

Footnotes

Competing interests:

R.S.E has no financial disclosures to report.

References

- [1].Parkinson J, An essay on shaking palsy. Sherwood, Neeley and Jones, 1817. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Berg D, Postuma RB, Bloem B, Chan P, Dubois B, Gasser T, et al. , Time to redefine PD? Introductory statement of the MDS Task Force on the definition of Parkinson’s disease, Mov Disord. 29 (2014) 454–462. doi: 10.1002/mds.25844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Postuma RB, Gagnon JF, Vendette M, Charland K, Montplaisir J, REM sleep behaviour disorder in Parkinson’s disease is associated with specific motor features, J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 79 (2008) 1117–1121. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2008.149195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Katz M, Luciano MS, Carlson K, Luo P, Marks WJ, Larson PS, et al. , Differential effects of deep brain stimulation target on motor subtypes in Parkinson’s disease, Ann. Neurol. 77 (2015) 710–719. doi: 10.1002/ana.24374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Giladi N, Mirelman A, Thaler A, Orr-Urtreger A, A Personalized Approach to Parkinson’s Disease Patients Based on Founder Mutation Analysis, Front. Neurol. 7 (2016) 71. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2016.00071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Clarimón J, Pagonabarraga J, Paisán-Ruíz C, Campolongo A, Pascual-Sedano B, Martí-Massó J-F, et al. , Tremor dominant parkinsonism: Clinical description and LRRK2 mutation screening, Mov Disord. 23 (2008) 518–523. doi: 10.1002/mds.21771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Reijnders JSAM, Ehrt U, Lousberg R, Aarsland D, Leentjens AFG, The association between motor subtypes and psychopathology in Parkinson’s disease, Parkinsonism & Related Disorders. 15 (2009) 379–382. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Eisinger RS, Hess CW, Martinez-Ramirez D, Almeida L, Foote KD, Okun MS, et al. , Motor subtype changes in early Parkinson’s disease, Parkinsonism & Related Disorders. (2017). doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2017.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Von Coelln FR, Barr E, Gruber-Baldini A, Reich S, Armstrong M, Shulman L, Motor Subtypes of Parkinson Disease are Unstable Over Time (S48.002), Neurology. 84 (2015) S48.002. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Erro R, Picillo M, Amboni M, Savastano R, Scannapieco S, Cuoco S, et al. , Comparing PIGD and Akinetic-Rigid subtyping of Parkinson Disease and their stability over time, European Journal of Neurology. (2019) ene.13968. doi: 10.1111/ene.13968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Poletti M, Frosini D, Pagni C, Baldacci F, Nicoletti V, Tognoni G, et al. , Mild cognitive impairment and cognitive-motor relationships in newly diagnosed drug-naive patients with Parkinson’s disease, J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 83 (2012) 601–606. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2011-301874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Wojtala J, Heber IA, Neuser P, Heller J, Kalbe E, Rehberg SP, et al. , Cognitive decline in Parkinson’s disease: the impact of the motor phenotype on cognition, J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 90 (2019) 171–179. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2018-319008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Greenland JC, Williams-Gray CH, Barker RA, The clinical heterogeneity of Parkinson’s disease and its therapeutic implications, European Journal of Neuroscience. 49 (2019) 328–338. doi: 10.1111/ejn.14094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].van Rooden SM, Heiser WJ, Kok JN, Verbaan D, van Hilten JJ, Marinus J, The identification of Parkinson’s disease subtypes using cluster analysis: A systematic review, Mov Disord. 25 (2010) 969–978. doi: 10.1002/mds.23116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Mestre TA, Eberly S, Tanner C, Grimes D, Lang AE, Oakes D, et al. , Reproducibility of data-driven Parkinson’s disease subtypes for clinical research, Parkinsonism & Related Disorders. (2018). doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2018.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Stebbins GT, Goetz CG, Burn DJ, Jankovic J, Khoo TK, Tilley BC, How to identify tremor dominant and postural instability/gait difficulty groups with the movement disorder society unified Parkinson's disease rating scale: Comparison with the unified Parkinson's disease rating scale, Mov Disord. 28 (2013) 668–670. doi: 10.1002/mds.25383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].van Rooden SM, Visser M, Verbaan D, Marinus J, van Hilten JJ, Motor patterns in Parkinson’s disease: a data-driven approach, Mov Disord. 24 (2009) 1042–1047. doi: 10.1002/mds.22512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Graham JM, Sagar HJ, A data-driven approach to the study of heterogeneity in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease: identification of three distinct subtypes, Mov Disord. 14 (1999) 10–20. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Erro R, Vitale C, Amboni M, Picillo M, Moccia M, Longo K, et al. , The Heterogeneity of Early Parkinson’s Disease: A Cluster Analysis on Newly Diagnosed Untreated Patients, PLoS ONE. 8 (2013) e70244. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Parkinson Progression Marker Initiative, The Parkinson Progression Marker Initiative (PPMI), Prog. Neurobiol. 95 (2011) 629–635. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Everitt B, Landau S, Leese M, Stahl D, Cluster Analysis, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Alvarado-Franco NL, Olguín-Ramírez L, Eisinger RS, Ramirez Zamora A, Cervantes-Arriaga A, Rodríguez-Violante M, et al. , Analysis of Parkinson’s disease motor subtypes: Mexican Registry of Parkinson - ReMePARK, Rev Mex Neuroci. 19 (2019) 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Selikhova M, Williams DR, Kempster PA, Holton JL, Revesz T, Lees AJ, A clinico-pathological study of subtypes in Parkinson’s disease, Brain. 132 (2009) 2947–2957. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Nutt JG, Motor subtype in Parkinson’s disease: Different disorders or different stages of disease? Mov Disord. 31 (2016) 957–961. doi: 10.1002/mds.26657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Fereshtehnejad SM, Zeighami Y, Dagher A, Clinical criteria for subtyping Parkinson’s disease: biomarkers and longitudinal progression, Brain. (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]