Abstract

Objective:

Unawareness, or anosognosia, of memory deficits is a challenging manifestation of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) that adversely affects a patient’s safety and decision-making. However, there is a lack of consensus regarding the presence, as well as the evolution, of altered awareness of memory function across the preclinical and prodromal stages of AD. Here, we aimed to characterize change in awareness of memory abilities and its relationship to beta-amyloid (Aβ) burden in a large cohort (N = 1,070) of individuals across the disease spectrum.

Methods:

Memory awareness was longitudinally assessed (average number of visits = 4.3) and operationalized using the discrepancy between mean participant and partner report on the Everyday Cognition scale (memory domain). Aβ deposition was measured at baseline using [18F]florbetapir positron emission tomographic imaging.

Results:

Aβ predicted longitudinal changes in memory awareness, such that awareness decreased faster in participants with increased Aβ burden. Aβ and clinical group interacted to predict change in memory awareness, demonstrating the strongest effect in dementia participants, but could also be found in the cognitively normal (CN) participants. In a subset of CN participants who progressed to mild cognitive impairment (MCI), heightened memory awareness was observed up to 1.6 years before MCI diagnosis, with memory awareness declining until the time of progression to MCI (−0.08 discrepant-points/yr). In a subset of MCI participants who progressed to dementia, awareness was low initially and continued to decline (−0.23 discrepant-points/yr), reaching anosognosia 3.2 years before dementia onset.

Interpretation:

Aβ burden is associated with a progressive decrease in self-awareness of memory deficits, reaching anosognosia approximately 3 years before dementia diagnosis.

The capability to accurately assess our cognitive abilities is crucial to function effectively. This is particularly important in the setting of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), when the deterioration of mental capacity can threaten even the most basic functions of everyday living. Unawareness of memory deficits, or anosognosia, is a challenging manifestation of AD that has been associated with increased hours of informal care, greater use of support services, and increased total family care costs.1,2 Despite the impact of anosognosia on patients and their caregivers, there is a lack of consensus regarding the presence, as well as the evolution, of altered awareness of memory function across the preclinical and prodromal stages of AD.

Anosognosia is a common symptom in patients with AD dementia, with a prevalence estimated to range between 21%3 and 81%,4 and the disorder has been shown to correlate with overall disease severity.5–9 Previous studies, conducted primarily in AD dementia, have reported that awareness decreases over time,10–12 whereas other studies have reported mixed results6,13 or no change.14–19 One longitudinal study examining 239 older adults with incident dementia showed that, on average, awareness of memory functioning declines 2 to 3 years before dementia onset.20 In contrast, awareness of cognitive dysfunction shown by individuals with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is highly variable, ranging from heightened awareness with marked concerns21 to complete unawareness about their cognitive difficulty.22,23

A recent publication using Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) data has demonstrated that amnestic MCI individuals with impaired awareness were harboring increased beta-amyloid (Aβ) burden, one of the hallmark pathologies of AD, as measured in vivo using [18F]florbetapir (FBP) positron emission tomography (PET).24 These findings have also been extended to cognitively normal (CN) older adults taking part of the INSIGHT-PreAD study, in which participants exhibiting low awareness showed increased cortical Aβ burden, as compared to CN participants with heightened awareness.25 In contrast, using cross-sectional data, Vannini and colleagues observed that heightened memory awareness was related to increased Aβ burden in CN participants from the Harvard Aging Brain Study.26 On the whole, the evolution of altered self-awareness of memory function across the preclinical and prodromal stages of AD is not fully understood. Specifically, it remains unclear as to which stage in the AD continuum anosognosia occurs and whether an individual’s self-judgment of his/her own cognitive abilities changes over the course of the disease as pathology increases.

The present study aimed to characterize change in awareness of memory abilities and its relationship to Aβ burden in a large cohort (N = 1,070) of individuals across the disease spectrum (CN, MCI, and dementia). Specifically, we aimed to (1) examine the change in memory self-awareness by baseline amyloid burden and clinical stage,(2) determine the onset of unawareness of memory deficits over the course of AD progression, and (3) determine predictive capabilities of low and/or high awareness for clinical progression. Overall, we hypothesized that altered memory self-awareness would be associated with baseline Aβ burden and that these initial pathophysiological changes would be associated with decreased memory self-awareness after longitudinal follow-up.

Subjects and Methods

Study Participants

This prospective study analyzed data from 1,070 participants enrolled in the ADNI (adni.loni.usc.edu). The ADNI is an ongoing, longitudinal, multicenter study conducted at 59 sites across North America, enrolling CN, amnestic MCI, and AD participants aged 55 to 94 years. The ADNI was launched in 2003 as a public–private partnership, led by principal investigator Michael W. Weiner, MD. The primary goal of the ADNI has been to test whether serial magnetic resonance imaging, PET, other biological markers, and clinical and neuropsychological assessment can be combined to measure the progression of MCI and early AD. For up-to-date information, see www.adni-info.org. Exclusion criteria included a history of alcoholism, drug abuse, and head trauma, as well as serious medical or psychiatric conditions. Cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine were only allowed in patients if they were stable for 3 months before screening. Moreover, antidepressants were allowed if participants were not significantly depressed at the time of screening and did not have a history of major depressive disorder within the past year. Institutional review board approvals and informed consents were obtained prior to all procedures. The global Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) obtained at the clinical assessment closest to each individual’s baseline PET was used as a diagnostic criterion for CN (CDR = 0), MCI (CDR = 0.5), and dementia (CDR ≥1) clinical groupings. Clinical progression of CN to MCI was defined as a global CDR increase from 0 at baseline to0.5 at final follow-up, and progression from MCI to dementia was defined as a global CDR increase from 0.5 at baseline to ≥1 at final follow-up. Baseline Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) in CN and MCI participants was ≥24.

Estimation of Awareness of Memory Performance

The memory functioning subtest of the Everyday Cognition (ECog) scale was used to estimate self-awareness of memory performance.27 ECog is a 39-item measure that was specifically developed to assess subjective cognitive decline and daily functioning abilities in older adults. The study partner and self-rated versions of the ECog are composed of identical questions, framed in the context of current performance compared to 10 years ago and scored on a Likert scale. Specifically, the discrepancy between the mean study partner-rated and the mean self-rated Everyday Memory 8-item subtest was used to assess memory self-awareness, as previously implemented in other ADNI studies.23,28 Using this approach, a negative score indicates an over-estimation of memory functioning or low memory awareness, meaning that these individuals believe they are functioning at a higher level than their partners have rated. In contrast, a positive score indicates underestimation of memory functioning or heightened memory awareness, meaning that these individuals believe they are functioning worse than their partners have rated. An awareness score of 0 indicates that the participant and the study partner judge memory similarly, suggesting that the participant has insight into his/her memory functioning. Additionally, we defined a threshold for anosognosia using the mean discrepancy score when participants are reporting significantly less difficulty than their study partners (see statistical analyses). Conversely, a threshold for heightened awareness was defined using the mean discrepancy score when participants are reporting significantly more difficulty than their study partner. Note that in the CN participants, we are using the term low awareness instead of anosognosia, as these individuals are still performing within normal limits on cognitive tests.

PET Imaging

Aβ burden was assessed for each participant at baseline using FBP-PET. FBP data were expressed as standard uptake volume ratio (SUVr; 50–70 minutes) in a large neocortical region scaled to cerebellar gray matter, including large areas of the frontal, lateral temporal, and parietal lobes. FBP SUVr was used as a continuous variable in all statistical analyses. However, a threshold set at SUVr = 1.1129–31 was used both for visualization purposes and for breaking down the interaction between baseline Aβ and baseline clinical stage.

Statistical Analyses

Participants were divided into 6 subgroups based on clinical stage (CN, MCI, or dementia) and Aβ status (high or low FBP binding). Two-sample t tests and chi-squared tests were used to examine differences in demographics and baseline ECog data for each group as compared to the low Aβ CN participants. Additional post hoc tests, using linear regression, examined awareness at baseline among clinical and Aβ groups. A linear mixed-effect model with time by participants as random factors was used to evaluate the association between baseline continuous measures of FBP binding, baseline clinical stages, and longitudinal changes in awareness, while adjusting for baseline age, sex, education, and apolipoprotein E4 (APOEε4) genotype. To evaluate whether the Aβ effect on longitudinal change in awareness increased over the disease spectrum, we computed the interactive effect of baseline Aβ, baseline diagnosis, and time on longitudinal awareness. The effects of baseline age and time were added as covariates, as well as time by subject as random factors. To further explore this 3-way interaction, the effects of baseline diagnosis and time were estimated in both high and low Aβ participants. Additionally, we computed the baseline Aβ by time effect within each diagnostic group (CN, MCI, and dementia).

To determine how much time before or after clinical progression anosognosia becomes evident in the AD course, we characterized longitudinal awareness in participants who clinically progressed. In CN-to-MCI and in MCI-to-dementia progressors, we computed linear mixed-effect models predicting awareness over time, with the time vector anchored on clinical progression (ie, time = 0 when progression occurs). We evaluated the significance of the intercept at different times (spotlight analysis) and computed a 5,000-trial bootstrap to provide 95% confidence intervals (CIs) around the time at which awareness was significantly nonzero (floodlight analysis). A threshold for low memory awareness/anosognosia was determined as the memory awareness index at that time (the Johnson–Neyman point), that is, the time when participants are reporting significantly less difficulty than their study partners do.32 Similarly, a threshold for heightened awareness was determined as the awareness index (the Johnson–Neyman point) when participants are reporting significantly more difficulty than their partners do. To validate these thresholds, we reported the proportion of participants with low awareness/anosognosia or heightened awareness at baseline in CN and MCI, and used age-adjusted logistic regression to evaluate whether low awareness/anosognosia or heightened awareness was associated with clinical progression. We illustrate these results by computing survival curves displaying the predictive power of these awareness thresholds for clinical progression. Statistics were performed in MATLAB R2018a (MathWorks, Natick, MA) and are reported with 2-tailed p values (α = 0.05).

Results

Cohort Characteristics and Baseline Awareness Measures

Table 1 shows participant characteristics and highlights the differences between clinical (CN, MCI, or dementia) and Aβ subgroups (low or high FBP). All groups are compared at baseline to low FBP CN participants. APOEε4 carriage was more frequent in high FBP CN than in low FBP CN participants (χ2 = 22.89, p < 0.001) and the proportion of APOEε4 carriers was higher in high FBP MCI and high FBP dementia (χ2 = 130.36, p < 0.001; χ2 = 94.63, p < 0.001). However, no APOEε4 carriers were found among low FBP dementia, preventing us from disentangling the contributions of APOEε4 carriage and FBP binding in dementia participants. Compared to low FBP CN, high FBP CN (t358 = 3.34, p < 0.001) and low FBP dementia (t254 = 3.52, p < 0.001) subjects were older, whereas low FBP MCI subjects were younger (t481 = −3.99, p < 0.001). [Correction added on December 11, 2019, after first online publication: In the preceding sentence, “AD” has been changed to “dementia.”] Sex was well balanced among groups, with high FBP CN being the only group having a larger percentage of females (χ2 = 9.06, p = 0.003). As expected, MMSE decreased with increasing CDR.

TABLE 1.

Demographic Information

| Subjects, n | 239 | 121 | 244 | 352 | 17 | 97 | 1,070 |

| APOEε4+, n (% of subsample) | 46 (19.3) | 52 (43.0)a | 56 (23.0) | 236 (67.1)a | 0 (0.0)a | 73 (75.3)a | 463 (43.2) |

| Female sex, n (% of subsample) | 112 (46.9) | 77 (63.6)b | 106 (43.4) | 150 (42.6) | 2 (11.8)b | 45 (46.4) | 492 (46.0) |

| Progression to MCI, n | 32 | 36 | — | — | — | — | 68 |

| Progression to dementia, n | 2 | 4 | 14 | 121 | — | — | 141 |

| Baseline age, yr, mean (SD) | 74.1 (6.7) | 76.5 (6.3)a | 71.3 (8.3)a | 74.1 (7.2) | 79.9 (6.3)a | 74.9 (8.3) | 73.9 (7.5) |

| Education, yr, mean (SD) | 16.7 (2.5) | 16.0 (2.8)b | 16.4 (2.5) | 16.1 (2.8)b | 16.2 (2.1) | 15.2 (2.8)a | 16.2 (2.7) |

| Baseline MMSE, mean (SD) | 29.1 (1.2) | 28.9 (1.2) | 28.1 (2.7)a | 26.8 (2.9)a | 21.6 (6.4)a | 22.4 (2.7)a | 27.4 (3.2) |

| Baseline logical memory, mean (SD) | 15.4 (4.0) | 14.9 (4.1) | 9.2 (5.0)a | 11.4 (5.5)a | 5.7 (5.5)a | 4.9 (3.6)a | 11.3 (5.9) |

| Baseline ECog memory score: participant, mean (SD) | 1.7 (0.5) | 1.7 (0.5) | 2.2 (0.7)a | 2.4 (0.7)a | 2.1 (0.7)a | 2.3 (0.8)a | 2.1 (0.7) |

| Baseline ECog memory score: partner, mean (SD) | 1.4 (0.5) | 1.4 (0.4) | 2.0 (0.7)a | 2.5 (0.8)a | 3.3 (0.5)a | 3.5 (0.5)a | 2.1 (0.9) |

| Baseline awareness index, mean (SD) | 0.3 (0.6) | 0.3 (0.5) | 0.3 (0.9) | −0.1 (0.9)a | −1.1 (1.0)a | −1.2 (1.0)a | −0.0006 (0.9) |

| ECog follow-up duration, yr, mean (SD) | 3.1 (1.4) | 3.0 (1.5) | 3.4 (1.6)b | 2.8 (1.6)b | 1.7 (1.6)a | 1.1 (1.0)a | 2.9 (1.6) |

| Number of ECog visits, mean (SD) | 4.1 (1.2) | 4.0 (1.3) | 5.0 (1.7)a | 4.5 (1.6)b | 3.1 (1.6)b | 2.6 (1.0)a | 4.3 (1.6) |

Subject information is presented across 6 levels of baseline diagnosis and baseline Aβ as well as the full sample (N = 1,070). Missing data: 5 participants did not have information regarding biological sex, 7 did not have APOEε4 status, and 5 did not have information regarding years of education.

Significantly different from CN, low amyloid (p < 0.001).

Significantly different from CN, low amyloid (p < 0.05).

APOEε4 = apolipoprotein E4 genotype; Aβ = beta-amyloid; CN = clinically normal; ECog = Everyday Cognition scale; MCI = mild cognitive impairment; MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination; SD = standard deviation.

Average ECog follow-up duration was 3.1 years in low FBP CN and 3.0 years in high FBP CN. Comparatively, low FBP MCI subjects had longer follow-up(3.4 years; t481 = −2.45, p = 0.01), whereas high FBP MCI (2.8 years; t589 = 1.99, p = 0.05), low FBP dementia(1.7 years; t254 = 3.87, p < 0.001), and high FBP dementia (1.1 years; t334 = 12.62, p < 0.001) participants had shorter follow-up ranges. From baseline to final clinical assessment, 68 participants progressed from CN to MCI and 135 participants progressed from MCI to dementia.

Using linear regression, the effects of FBP group and clinical status interacted at baseline (t1,066 = −4.05, β = −1.90, p < 0.001). In post hoc analyses looking within clinical groups, baseline awareness did not significantly differ by FBP group within CN as well as dementia participants (t358 = 0.87, p = 0.38; t112 = −0.35, p = 0.72), yet differed significantly within MCI participants (t594 = −4.61, p < 0.001). In comparison to low FBP CN participants, baseline awareness was not significantly different in low FBP MCI participants (t481 = 0.42, p = 0.67), but was significantly lower in high FBP MCI (t589 = −5.61, p < 0.001) as well as in both low and high FBP dementia participants (t254 = −9.50, p < 0.001; t334 = −18.05, p < 0.001).

Change in Awareness by Baseline FBP Binding and Clinical Group

Baseline FBP binding was the most significant predictor of longitudinal changes in awareness (Table 2; β = −0.22, p < 0.001), such that awareness decreased faster in participants with high FBP SUVr. Baseline clinical group, age, and APOEε4 carriage were also significant, such that awareness decreased faster in participants with advanced clinical status (ie, higher global CDR; β = −0.07, p = 0.03) and older age (β = −0.003, p = 0.005), and in APOEε4 carriers (β = −0.05, p = 0.007). Adjusting for the Geriatric Depression Scale score did not alter the results.

TABLE 2.

Effects of Independent Variables on Longitudinal Awareness

| Intercept | 1.82 | 0.33 | 4,527 | 5.47 | <0.001a |

| Baseline age | −0.02 | 0.003 | 4,527 | −4.42 | <0.001a |

| Baseline Aβ | −0.44 | 0.13 | 4,527 | −3.53 | <0.001a |

| Time | 0.55 | 0.10 | 4,527 | 5.22 | <0.001a |

| Female sex | 0.07 | 0.05 | 4,527 | 1.28 | 0.20 |

| APOEε4+ | −0.008 | 0.06 | 4,527 | −0.14 | 0.89 |

| Years of education | 0.01 | 0.009 | 4,527 | 1.33 | 0.18 |

| Baseline DX | −1.08 | 0.09 | 4,527 | −12.62 | <0.001a |

| Baseline age:time | −0.003 | 0.001 | 4,527 | −2.82 | 0.005b |

| Baseline Aβ:time | −0.22 | 0.04 | 4,527 | −5.42 | <0.001a |

| Time:female sex | −0.007 | 0.02 | 4,527 | −0.42 | 0.67 |

| Time:APOEε4+ | −0.05 | 0.02 | 4,527 | −2.68 | 0.007b |

| Time:years of education | −0.005 | 0.003 | 4,527 | −1.65 | 0.10 |

| Time:baseline DX | −0.07 | 0.03 | 4,527 | −2.21 | 0.03b |

p < 0.001.

p < 0.05.

APOEε4 = apolipoprotein E4 genotype; Aβ = beta-amyloid; DX = diagnosis; SE = standard error.

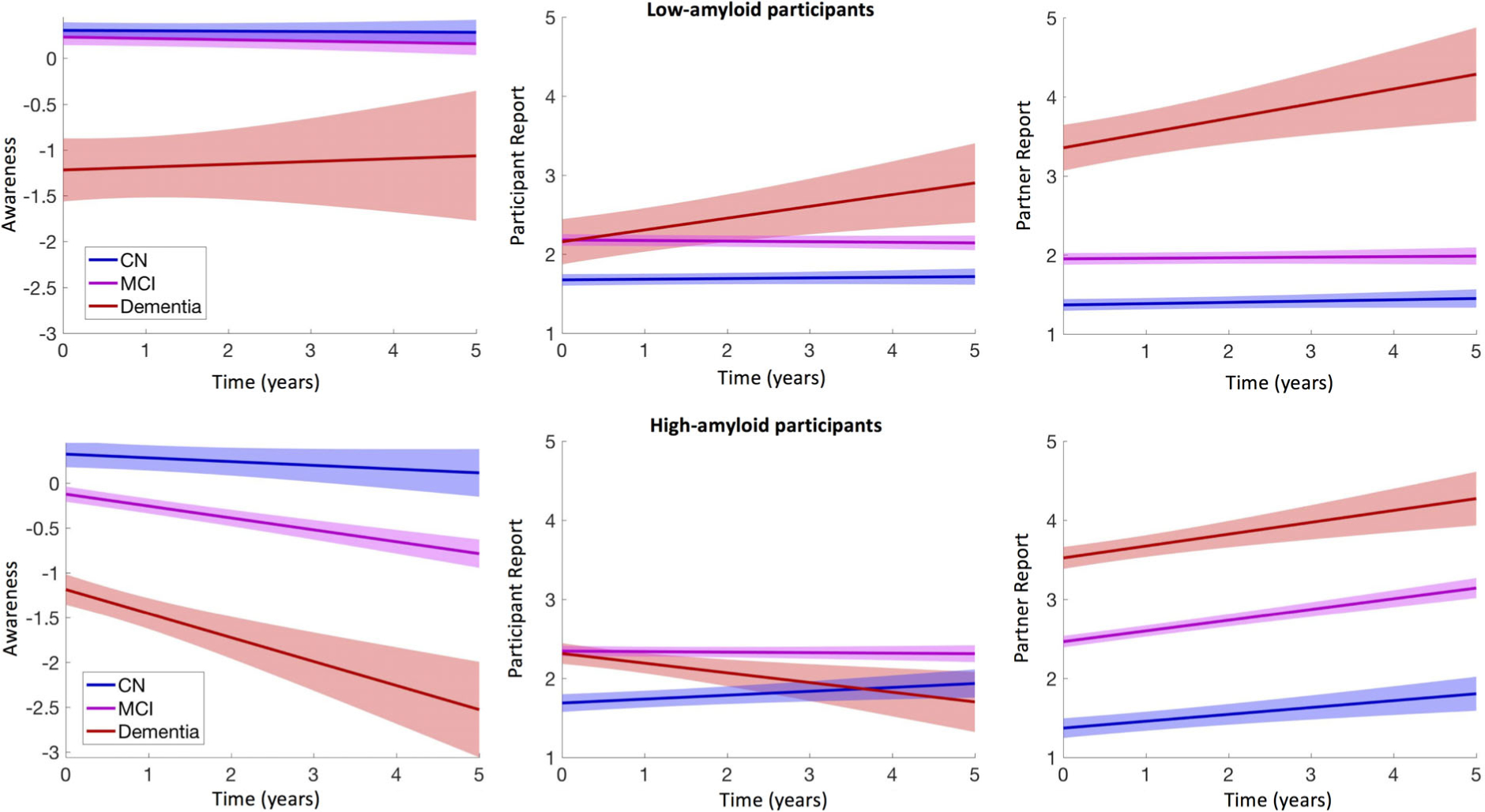

Baseline FBP and baseline clinical group interacted to predict longitudinal awareness (Table 3 and Fig 1), such that the effect of FBP on decreasing awareness increased with advanced clinical status. When breaking down the interaction, we observed that baseline clinical status only had an effect in high FBP participants and had no effect in low FBP participants (Table 4). Although FBP binding had the most significant effect on awareness changes in the dementia group (Table 5; β = −0.57, p = 0.002), followed by MCI (β = −0.30, p < 0.001), it also had a significant effect in CN (β = −0.12, p = 0.02), suggesting that awareness starts to decrease in the preclinical stage of the disease.

TABLE 3.

Interactive Effect of Diagnosis and Aβ on Longitudinal Awareness: All Subjects

| Intercept | 1.29 | 0.31 | 4,552 | 4.13 | <0.001a |

| Baseline age | −0.02 | 0.003 | 4,552 | −5.06 | <0.001a |

| Baseline Aβ | 0.30 | 0.19 | 4,552 | 1.57 | 0.12 |

| Time | 0.27 | 0.10 | 4,552 | 2.57 | 0.01b |

| Baseline DX | 0.89 | 0.43 | 4,552 | 2.07 | 0.04b |

| Baseline age:time | −0.002 | 0.001 | 4,552 | −1.91 | 0.06 |

| Baseline Aβ:time | −0.13 | 0.06 | 4,552 | −1.98 | 0.05b |

| Baseline Aβ:baseline DX | −1.65 | 0.35 | 4,552 | −4.72 | <0.001a |

| Time:baseline DX | 0.34 | 0.16 | 4,552 | 2.13 | 0.03b |

| Baseline Aβ:time:baseline DX | −0.36 | 0.14 | 4,552 | −2.63 | 0.009b |

p < 0.001.

p < 0.05.

Aβ = beta-amyloid; DX = diagnosis; SE = standard error.

FIGURE 1:

Awareness of memory deficits decreases over time in high-amyloid participants. Left: Longitudinal changes in awareness (discrepant-points between participants and partners) in low (top row) and high (bottom row) amyloid participants. Middle: Longitudinal changes in participants’ self-complaints about memory deficits over time. Higher values are indicative of more severe memory difficulty reports. Right: Longitudinal changes in partners’ complaints about memory deficits over time. Higher values are indicative of more severe memory difficulty reports. In high-amyloid cognitively normal (CN), mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and dementia participants, self-complaints do not increase over time as much as partners’ complaints increase, resulting in a progressive decrease in memory awareness. [Correction added on December 11, 2019, after first online publication: In the preceding sentence, “Alzheimer disease” has been changed to “dementia.”] Shading represents 95% confidence intervals. All plots are adjusted for age and sex.

TABLE 4.

Interactive Effect of Diagnosis and Aβ on Longitudinal Awareness: High/Low Aβ

| High Aβ | |||||

| Intercept | 0.97 | 0.37 | 2,303 | 2.61 | 0.009a |

| Baseline age | −0.006 | 0.005 | 2,303 | −1.32 | 0.19 |

| Time | 0.31 | 0.15 | 2,303 | 2.12 | 0.03a |

| Baseline DX | −1.48 | 0.12 | 2,303 | −12.83 | <0.001b |

| Baseline age:time | −0.005 | 0.002 | 2,303 | −2.42 | 0.02a |

| Time:baseline DX | −0.21 | 0.05 | 2,303 | −3.91 | <0.001b |

| Low Aβ | |||||

| Intercept | 2.17 | 0.31 | 2,247 | 7.02 | <0.001b |

| Baseline age | −0.02 | 0.004 | 2,247 | −5.84 | <0.001b |

| Time | 0.04 | 0.09 | 2,247 | 0.42 | 0.68 |

| Baseline DX | −0.63 | 0.12 | 2,247 | −5.45 | <0.001b |

| Baseline age:time | −0.0006 | 0.001 | 2,247 | −0.54 | 0.59 |

| Time:baseline DX | −0.002 | 0.04 | 2,247 | −0.06 | 0.96 |

p < 0.05.

p < 0.001.

Aβ = beta-amyloid; DX = diagnosis; SE = standard error.

TABLE 5.

Effect of Amyloid on Longitudinal Awareness Within Each Diagnostic Group

| CN | |||||

| Intercept | 0.63 | 0.33 | 1,457 | 1.91 | 0.06a |

| Baseline age | −0.007 | 0.004 | 1,457 | −1.65 | 0.10 |

| Baseline Aβ | 0.16 | 0.15 | 1,457 | 1.11 | 0.27 |

| Time | 0.26 | 0.12 | 1,457 | 2.10 | 0.04a |

| Baseline age:time | −0.002 | 0.001 | 1,457 | −1.24 | 0.22 |

| Baseline Aβ:time | −0.12 | 0.05 | 1,457 | −2.36 | 0.02a |

| MCI | |||||

| Intercept | 1.93 | 0.36 | 2,792 | 5.36 | <0.001b |

| Baseline age | −0.01 | 0.005 | 2,792 | −2.99 | 0.003a |

| Baseline Aβ | −0.73 | 0.16 | 2,792 | −4.65 | <0.001b |

| Time | 0.46 | 0.11 | 2,792 | 4.25 | <0.001b |

| Baseline age:time | −0.002 | 0.001 | 2,792 | −1.70 | 0.09 |

| Baseline Aβ:time | −0.30 | 0.05 | 2,792 | −6.03 | <0.001b |

| Dementia | |||||

| Intercept | −0.48 | 1.05 | 295 | −0.46 | 0.65 |

| Baseline age | −0.01 | 0.01 | 295 | −1.03 | 0.30 |

| Baseline Aβ | 0.07 | 0.36 | 295 | 0.20 | 0.84 |

| Time | 0.41 | 0.59 | 295 | 0.69 | 0.49 |

| Baseline age:time | 0.002 | 0.007 | 295 | 0.30 | 0.76 |

| Baseline Aβ:time | −0.57 | 0.19 | 295 | −3.06 | 0.002a |

p < 0.05.

p < 0.001.

Aβ = beta-amyloid; CN = clinically normal; MCI = mild cognitive impairment; SE = standard error.

Figure 1 (middle and right panels) separately illustrate the participant-rated and partner-rated versions of the ECog. It shows that low FBP dementia participants reported more difficulty over time (top row, middle plot; β = 0.19, p = 0.001), together with their partners (β = 0.17, p = 0.001), resulting in stable awareness (left plot; β = 0.02, p = 0.85). High FBP dementia participants reported less difficulty over time (bottom row, middle), whereas their study partners reported more difficulty over time (right plot), resulting in decreasing memory awareness that is specific for high FBP participants. These observations are, however, limited by the short follow-up of participants with dementia. It is noteworthy that high FBP MCI participants did not change their assessments over time (middle plot), whereas their partners progressively reported increased memory difficulty (right plot). Although high FBP CN participants did increase their reports of memory difficulty over the course of the study, they did so to a lesser extent than their partners.

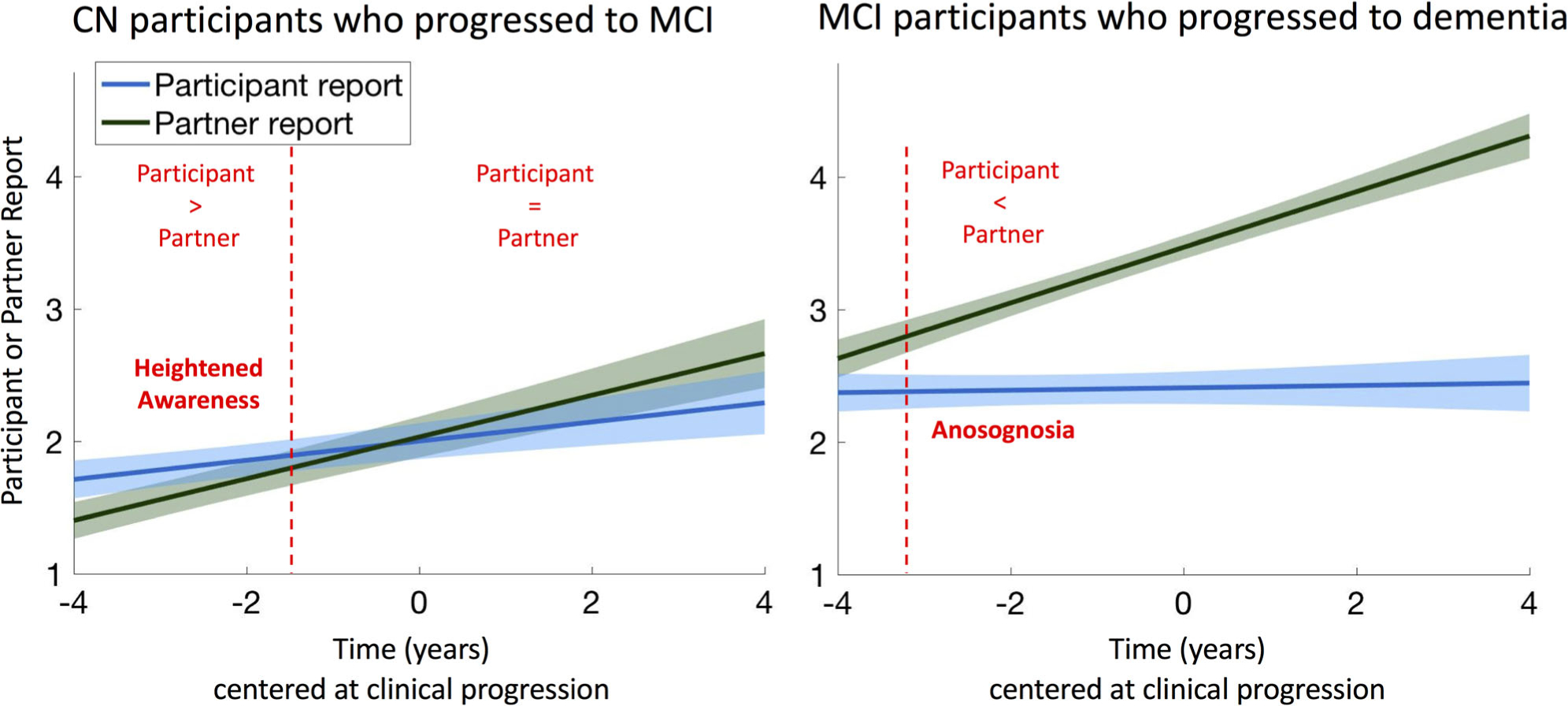

Evaluating the Change of Memory Self-Awareness Across the AD Spectrum

To investigate how self-awareness of memory functioning changes across the AD spectrum, we conducted a sub-analysis on participants who clinically progressed over the course of the study. Clinical progression of CN to MCI was defined as a global CDR increase from 0 at baseline to 0.5 at follow-up, and progression from MCI to dementia was defined as a global CDR increase from 0.5 at baseline to ≥1 at follow-up. For this analysis, we modified our time vector to define time = 0 as the year when participants progressed (rather than defining time = 0 as the time of PET imaging). By doing so, we anchored all changes to clinical progression (Fig 2).

FIGURE 2:

Significant anosognosia is observed 3 years before progression to dementia. Longitudinal changes in participants’ self-complaints and partners’ complaints in cognitively normal (CN; n = 68) and mild cognitive impairment (MCI; n = 135) participants who clinically progressed during the study. Slopes were obtained from a linear mixed effect model with random intercept and slope predicting complaints over time, adjusting for age and sex. Dotted lines are located at −1.6 years and + 3.2 years.

In the 68 CN participants who progressed to MCI, the discrepancy score was close to zero (ie, normal insight) at the time of MCI progression, as the reports of memory difficulty did not significantly differ between the participants and their partners (Table 6; p = 0.64). In general, CN participants reported more memory difficulty than their study partners up to 1.6 years before progression to MCI (95% CI around the Johnson–Neyman point = −0.5 to 4.3 years), indicating a state of heightened awareness. This is equivalent to an awareness index of +0.20, that is, a 1-point difference on at least 2 of the 8 items of the ECog memory scale. However, memory awareness decreased over time (−0.08 discrepant-points/yr, p = 0.002), reaching an awareness index close to 0 at approximately the time of MCI diagnosis.

TABLE 6.

Floodlight and Spotlight Analyses for Diagnostic Progression

| CN to MCI, n = 68 | |||||

| Intercept, 4 years before MCI | 0.36 | 0.09 | 295 | 3.77 | <0.001a |

| Intercept, 3 years before MCI | 0.28 | 0.08 | 295 | 3.40 | <0.001a |

| Intercept, 2 years before MCI | 0.20 | 0.08 | 295 | 2.64 | 0.009b |

| Intercept, 1 years before MCI | 0.12 | 0.08 | 295 | 1.56 | 0.12 |

| Intercept, at the time of MCI | 0.04 | 0.09 | 295 | 0.47 | 0.64 |

| Time | −0.08 | 0.03 | 295 | 3.12 | 0.002b |

| MCI to dementia, n = 135 | |||||

| Intercept, 4 years before dementia | −0.03 | 0.12 | 592 | −0.23 | 0.82 |

| Intercept, 3 years before dementia | −0.26 | 0.10 | 592 | 2.67 | 0.007b |

| Intercept, 2 years before dementia | −0.49 | 0.07 | 592 | −6.48 | <0.001a |

| Intercept, 1 years before dementia | −0.71 | 0.06 | 592 | −11.3 | <0.001a |

| Intercept, at the time of dementia | −0.94 | 0.06 | 592 | −14. 72 | <0.001a |

| Time | −0.23 | 0.03 | 592 | −7.68 | <0.001a |

p < 0.001.

p < 0.05.

CN = clinically normal; MCI = mild cognitive impairment; SE = standard error.

In the 135 MCI participants who progressed to dementia, reports of memory difficulty were different between participants and partners at the time of dementia progression (see Table 6; p < 0.001), with awareness decreasing over time (−0.23 discrepant-points/yr, p < 0.001), indicating a progressively lower awareness. Low awareness, that is, a significantly lower participant-rated than partner-rated ECog score, was observed in MCI participants 3.2 years (95% CI = 2.8–4.4 years) before progression to dementia. This was equivalent to an awareness index of −0.26, that is, a 1-point difference on at least 3 of the 8 items of the ECog memory scale.

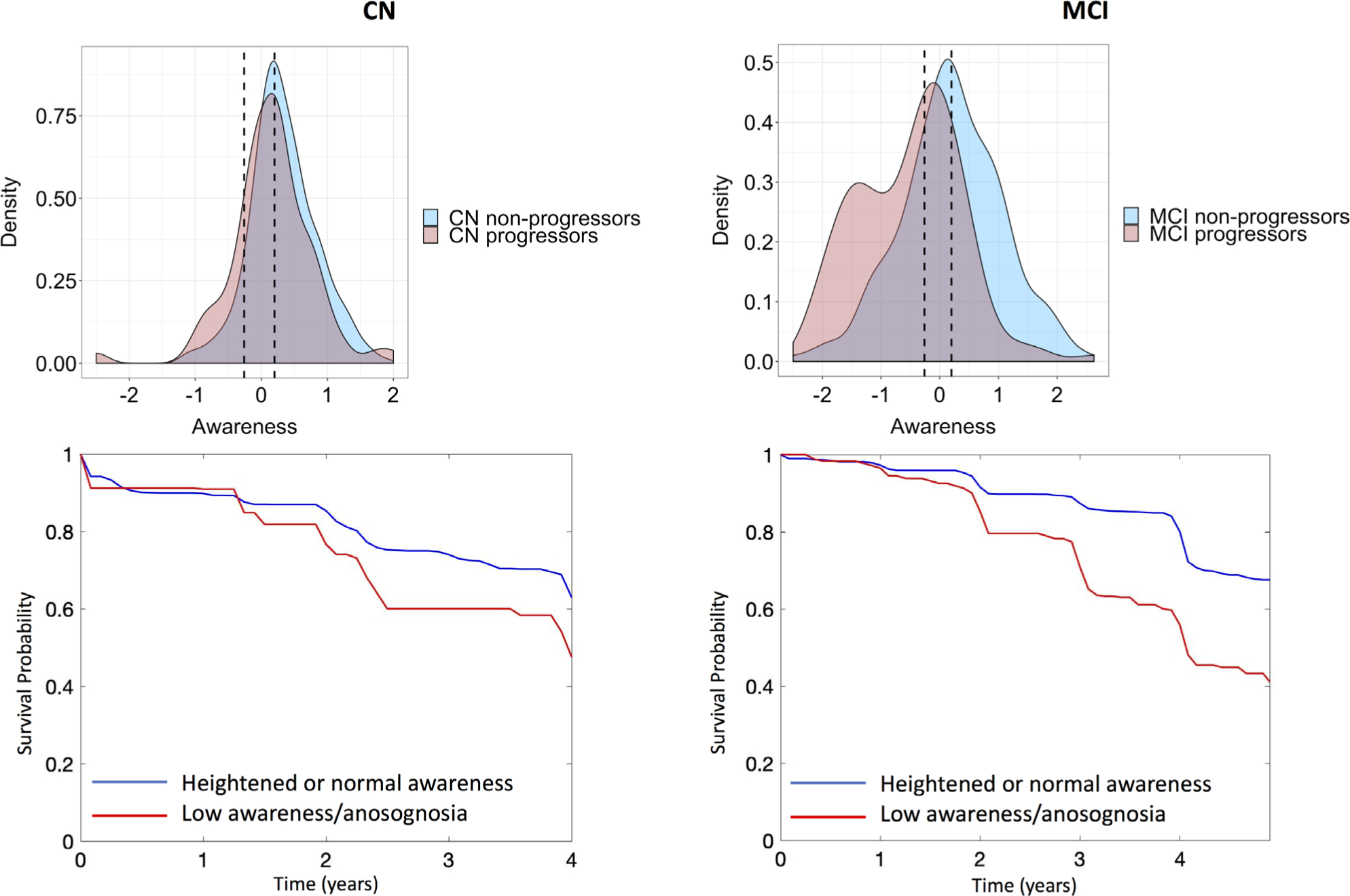

Evaluating Whether Low or High Baseline Awareness Predicts Clinical Progression

Figure 3 (top row) illustrates density plots of the awareness measures at baseline for CN and MCI participants who progressed and who did not progress over the course of the study. Using the thresholds for low awareness/anosognosia and heightened awareness derived in our floodlight analyses presented above, we calculated the prevalence of these two states in our CN and MCI participants at baseline. We found that 46 CN (14%) and 214 MCI (36%) participants could be defined as exhibiting low awareness/anosognosia, whereas 207 CN (58%) and 260 MCI (44%) participants could be defined as exhibiting heightened awareness. In CN, both the continuous awareness index (β = +2.6, p = 0.01) and the binary low awareness category (β = +2.1, p = 0.038) predicted progression to MCI. In contrast, heightened awareness was not predictive (β = −1.46, p = 0.14). In MCI, both continuous (β = +5.7, p < 0.001) and binary (β = +7.4, p < 0.001) measures of low awareness strongly predicted progression to dementia (see Fig 3, bottom row). MCI participants with heightened awareness had a lower risk of progression compared to the MCI subjects who had normal awareness (β = −5.5, p < 0.001).

FIGURE 3:

Anosognosia in cognitively normal (CN) and mild cognitive impairment (MCI) participants predicts future clinical progression. Top row: Kernel density plots of awareness for the CN (left) and MCI (right) participants who clinically progressed or remained stable. The left and right dotted lines are the awareness thresholds for significant anosognosia (−0.26) and heightened awareness (+0.20), respectively. Bottom row: Survival curves indicating the probability of remaining stable within a diagnostic group for CN and MCI participants with low awareness/anosognosia versus those with normal or heightened awareness at baseline.

Adjusting for FBP SUVr, MMSE, or memory (logical memory test, delayed story recall) at baseline did not modify the results, such that anosognosia predicted a greater risk of subsequent progression to dementia in MCI participants with equal amyloid burden and memory performance. Similar, albeit weaker, results were observed in CN participants.

Discussion

The present study aimed to characterize change in awareness of memory abilities and its relationship to Aβ burden in a large cohort of individuals across the AD spectrum. We observed that although Aβ burden was not associated with awareness at baseline in CN participants, Aβ was associated with decreasing participant awareness after longitudinal follow-up and with increasing levels of clinical impairment. In those CN subjects who progressed clinically to MCI during the course of the study, the participants themselves appeared to be the first to report difficulty with their memory, but as awareness decreased during the preclinical stage, at the time of MCI diagnosis participant and study partner complaints were equivalent. Awareness continued to decrease during the MCI stage; low awareness/anosognosia, that is, study partners reporting significantly more difficulty than participants, was observed on average 3 years before progression to dementia. Notably, using the full cohort we found that low awareness/anosognosia in both CN (13%) and MCI (36%) subjects predicted clinical progression, whereas heightened awareness in CN (58%) and MCI (44%) subjects did not. These results suggest that individuals who are unaware of memory changes may represent a specific group at risk for clinical progression and provide additional support for the usefulness of informant-reported decline.

Although there has been extensive work on the behavioral characterization of anosognosia at the stage of AD dementia (eg, see overview in Kaszniak and Edmonds33), our knowledge of the pathological mechanisms underlying anosognosia as well as the evolution of altered awareness of memory function across the earlier AD spectrum is very limited. Our knowledge about unawareness of memory impairment was limited for a long time to cross-sectional studies or longitudinal studies of prevalent dementia, suggesting that anosognosia was a variable feature of the dementia syndrome. However, as more recent studies have started to emerge, it has become clear that anosognosia is present in a relevant number of cases of individuals with MCI (see reviews by Roberts et al34 Starkstein35), and furthermore, the syndrome has been related to an increased rate of progression to AD dementia.9,23,24,36 Previous studies also suggest that anosognosia can be linked to AD pathophysiology. For instance, in one of the first postmortem studies, Marshall et al37 found that anosognosia is associated with medial temporal Aβ plaque burden in moderate to severe AD dementia. In addition, using fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET, Salmon and colleagues found that anosognosia in AD patients was related to decreased glucose metabolism in the temporoparietal junction.38 Moreover, using ADNI data, Therriault and colleagues found that MCI individuals with impaired awareness had decreased FDG metabolism as well as increased amyloid burden in the default mode network (eg, posterior cingulate cortex),24 in brain regions that have been shown to be both vulnerable to early AD pathology and important for self-referential processing.39,40

In addition, recent studies have extended these findings to preclinical AD.25,41,42 Specifically, in a cross-sectional study, Cacciamani and colleagues reported that CN participants who were unaware of memory deficits in everyday life, as noticed by their study partner, showed greater amyloid burden and lower cortical metabolism as compared to CN participants with high levels of awareness, suggesting that low awareness could be a useful marker of preclinical AD.25 In line with these findings, we found that amyloid was associated with decreases in awareness over time, and that awareness was predictive of subsequent clinical progression in individuals who were CN at baseline. Post hoc analyses revealed that awareness declined over the clinical stages, reaching the lowest scores at the stage of dementia (see Table 1). However, at the dementia stage we did not find a significant change between the Aβ groups, suggesting equal decreases in awareness. Note that at the dementia stage we had only 17 Aβ− participants, thus limiting conclusions to be drawn from that group. At the stage of MCI, we found a significant group effect such that Aβ+ participants had significantly decreased awareness as compared to the Aβ− participants, replicating both previous studies using ADNI data to investigate awareness in MCI,23,24 as well as our previous findings from the Harvard Aging Brain Study.26 However, we did not find a significant main effect of Aβ in the CN participants at baseline, indicating that awareness was the same at the start of the study in this cohort. These results are in contrast to previous findings by Cacciamani and colleagues25 as well as Vannini and colleagues,26 the latter demonstrating that increased amyloid was associated with heightened awareness in CN older participants. These discrepant findings could be due to several causes. For instance, the method to calculate awareness of memory is a factor to consider. Vannini and colleagues used discrepancy scores between subjective memory concerns and actual memory performance on an objective task, whereas Cacciamani and colleagues took a similar approach to the current study by using the Healthy Aging Brain Care Monitor43 questionnaire, which was administered to both the participants and their study partners. However, the most important issue is perhaps difference in the time to clinical progression in the different studies. That is, it could be hypothesized that levels of self-awareness vary on a continuum, starting with normal awareness of memory function, followed by a phase of heightened awareness with objectively normal memory performance, and lastly unawareness. The differential results from Cacciamani and colleagues and Vannini and colleagues support this notion, although future longitudinal studies in these cohorts will be necessary to evaluate how the participants’ awareness changes over time. Furthermore, inclusion criteria of the previous studies were different. For instance, in the study by Cacciamani and colleagues, only participants with subjective memory complaints were assessed. This was not the case in the study by Vannini and colleagues, as well as the current study (as the ADNI only introduced these criteria in later studies). We acknowledge that it will be important to address the inter-relationships between subjective memory complaints and awareness more thoroughly. Thus, future studies in which CN with and without subjective memory complaints are recruited at baseline would be helpful to address this issue.

As alluded to above, one important issue to keep in mind when discussing previous work investigating anosognosia is that it can be considered a multidimensional concept with no single clear conceptual and theoretical model or definition.34 Although a majority of studies have used a discrepancy score between participants and their study partner for assessing a level of awareness, other studies have used clinical judgment or comparison of participants’ self-assessment and objective task performance, which are other strategies that have been used to assess anosognosia in AD.44 To this end, apart from clinical judgment, we also acknowledge that there is a lack of operational criteria in assigning an anosognosia diagnosis. In this study, we propose a new methodological approach to define anosognosia and/or heightened awareness that could be used in research projects that handle discrepancy scores between self and informant report or self and objective test performance, and would like to define these states empirically. Using this approach, a threshold for low awareness was determined as having a discrepancy score of −0.26, corresponding to approximately 3.2 years (95% CI = 2.8–4.4 years) before progression to dementia. This would be equivalent to a 1-point difference on at least 3 of the 8 items on the ECog memory scale. This ADNI sample was limited in that few CN participants progressed to dementia, restricting our analyses to CN individuals who progressed to MCI, as well as MCI subjects who progressed to dementia. Nonetheless, these results are similar to the findings of Wilson and colleagues, who reported that in 2,092 individuals who were CN at baseline, awareness started to decline approximately 2.6 years before their dementia diagnosis.20 Moreover, using our linear mixed effects model to evaluate awareness over time in individuals who were considered CN at baseline but progressed clinically revealed that they generally reported more difficulty in memory than their study partner, indicating a state of heightened awareness. However, their awareness score decreased over time (−0.08 discrepant-points/yr), reaching almost equivalent discrepancy scores at the time of MCI diagnosis. Using this approach, a threshold for heightened awareness was determined as having a discrepancy score of +0.20, corresponding to approximately1.6 years (95% CI = −0.5 to 4.3 years) before progression to MCI.

The frequencies of low and heightened awareness we observed in this study are very similar to previous findings involving CN participants. For instance, Cacciamani and colleagues found that within a cohort of 318 CN older adults, 19 participants (6%) had low awareness and 86 participants (27%) had high awareness.25 Similarly, Sánchez-Benavides and colleagues recently found that in a cohort of 2,640 participants from the ALFA cohort, 173 participants (6.6%) had low awareness and 568 participants(21.5%) had high awareness.41 Of greater significance, we observed that in both CN and MCI participants low awareness predicted clinical progression, whereas MCI participants with heightened awareness had a lower risk of progression. Not only do these MCI results replicate previous ADNI findings showing that low awareness predicts clinical progression,24 as well as our previous finding,9 but they also extend those findings by showing that heightened awareness does not predict clinical progression. We acknowledge that our findings in CN participants may seem contradictory, such that in the floodlight analysis we report that our CN participants displayed more memory difficulty than their study partners, but in our logistic regression analysis we found that low awareness (not heightened awareness) predicted progression to MCI. We interpret these findings in the following 2 ways.

First, we believe that these data must be considered in relation to the proximity to clinical progression. That is, all our data indicate that awareness decreases over time from the preclinical AD stage. Thus, the tipping point for showing symptoms of unawareness of memory loss likely occurs in close proximity to the onset of cognitive symptoms. Second, as can be observed in Figure 1 (left panel) and even better in the density plots (see Fig 3), all CN and MCI participants had an overall tendency to show heightened awareness. Notably, all CN participants (both participants who progressed to MCI and CN participants who did not progress to MCI) had an overall tendency to complain about their memory. Due to this overlap, that is, nonprogressing participants also complaining about their memory, heightened awareness became a non-predictive measure of progression to MCI. This again highlights the importance of assessing these measures over time, as self-awareness likely varies over the course of the disease. Heightened awareness may occur for reasons other than AD pathology, for example, anxiety or fear of potentially developing dementia (nosophobia), psychoaffective disorders such as neuroticism,45 depression,46 and sleep disorders,47 or normal age-related changes, leading normal older individuals to complain about their memory more than their partners. When adjusting analyses for one such potential contributing factor to heightened awareness, depressive symptoms, we again found more CN and MCI participants with heightened awareness who did not progress as compared to CN and MCI participants who progressed. This suggests that non-AD factors contributing to heightened awareness are likely varied and multifactorial, which will be an important area of future investigation. The limited duration of follow-up in our study warrants longer follow-up in CN individuals as well.

Several limitations of this study should be noted. As mentioned above, the ADNI cohort has very few CN individuals who, so far, have progressed to dementia, especially given the relatively short duration of follow-up. For those reasons, and in regard to the discussion above about whether heightened awareness may predict progression to dementia, we acknowledge that our findings warrants further studies that investigate CN individuals during a longer follow-up period, and perhaps more frequently, to map out the very early changes in memory self-awareness that may occur during the preclinical period of the disease. In addition, and as also mentioned above, to date there is no consensus on how to optimally assess anosognosia in AD, but see Starkstein35 for more information. Here, we used a discrepancy score between participant self-assessment and study partner assessment, an approach that has been used in several previous publications investigating anosognosia in AD. We also acknowledge that the current study only assessed awareness based on memory reports, not taking into account other cognitive domains (eg, language, executive function). As patients and their partners often report nonmemory complaints, future studies should investigate the specificity of awareness of memory as compared to other cognitive domains, as this may be an important clinical issue. Finally, the current study only considered brain amyloidosis as a central neuropathological event in anosognosia and thus might not fully explain whether altered self-awareness is an independent symptom with a unique pathobiology or whether it is part of the AD symptom complex. Specifically, studies evaluating the relationships between tau and anosognosia should be conducted in the future. These limitations also underscore the importance of replicating these findings in other large cohorts following CN individuals over long periods of time.

We conclude that altered memory self-awareness is associated with baseline Aβ burden and these initial pathophysiological changes are associated with decreased self-awareness after longitudinal follow-up. Unawareness of memory change is observed approximately 3 years before clinical progression to dementia. Low awareness, not heightened awareness, predicted clinical progression from CN to MCI, providing further evidence for the notion that individuals who are unaware of cognitive change may represent a specific risk group as well as additional support for the usefulness of informant-reported decline.

Acknowledgment

Data collection and sharing for this project was funded by the ADNI (NIH U01 AG024904 (NIANIA) and Department of Defense W81XWH-12-2-0012). The ADNI is funded by the NIH National Institute on Aging and the NIH National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and through generous contributions from the following: AbbVie, Alzheimer’s Association, Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation, Araclon Biotech, BioClinica, Biogen, Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, CereSpir, Cogstate, Eisai, Elan Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly and Company, EuroImmun, F. Hoffmann-La Roche and its affiliated company Genentech, Fujirebio, GE Healthcare, IXICO, Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research & Development, Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development, Lumosity, Lundbeck, Merck & Co, Meso Scale Diagnostics, NeuroRx Research, Neurotrack Technologies, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, Pfizer, Piramal Imaging, Servier, Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, and Transition Therapeutics. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research provides funds to support ADNI clinical sites in Canada. Private sector contributions are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (www.fnih.org). The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer’s Therapeutic Research Institute at the University of Southern California. ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at the University of Southern California.

Footnotes

Data used in preparation of this article were obtained from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database (adni.loni.usc.edu). As such, the investigators within the ADNI contributed to the design and implementation of the ADNI and/or provided data but did not participate in analysis or writing of this report. A complete listing of ADNI investigators can be found at: http://adni.loni.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/how_to_apply/ADNI_Acknowledgement_List.pdf

Potential Conflicts of Interest

None.

References

- 1.Turro-Garriga O, Garre-Olmo J, Vilalta-Franch J, et al. Burden associated with the presence of anosognosia in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychatr 2013;28:291–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turro-Garriga O, Garre-Olmoa J, Rene-Ramırez R, et al. Consequences of anosognosia on the cost of caregivers’ care in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 2016;54:1551–1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Starkstein SE, Brockman S, Bruce D, Petracca G. Anosognosia is a significant predictor of apathy in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuropsychiatr Clin Neurosci 2010;22:378–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reed BR, Jagust WJ, Coulter L. Anosognosia in Alzheimer’s disease: relationships to depression, cognitive function, and cerebral perfusion. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 1993;15:231–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGlynn SM, Kaszniak AW. When metacognition fails: impaired awareness of deficit in Alzheimer’s disease. J Cogn Neurosci 1991;3: 181–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McDaniel KD, Edland SD, Heyman A. Relationship between level of insight and severity in Alzheimer’s disease. CERAD Clinical Investigators. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disorders 1995;9:101–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zanetti O, Vallotti B, Frisoni GB, et al. Insight in dementia: when does it occur? Evidence for a non-linear relationship between insight and cognitive status. J Gerontol 1999;54:100–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sevush S, Leve N. Denial of memory deficit in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry 1993;150:748–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Munro CE, Donovan NJ, Amariglio RE, et al. The impact of awareness of and concern about memory performance on the prediction of progression from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer disease dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2018;26:896–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Starkstein SE, Chemerinski E, Sabe L, et al. Prospective longitudinal study of depression and anosognosia in Alzheimer’s disease. Br J Psychiatry 1997;171:47–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vasterling JJ, Seltzer B, Watrous WE. Longitudinal assessment of deficit unawareness in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol 1997;10:197–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Derouesne C, Thibault S, Lagha-Pierucci S, et al. Decreased awareness of cognitive deficits in patients with mild dementia of the Alzheimer type. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1999;14:1019–1030. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akai T, Hanyu H, Sakurai H, et al. Longitudinal patterns of unawareness of memory deficits in mild Alzheimer’s disease. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2009;9:16–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kiyak HA, Teri L, Borson S. Physical and functional health assessment in normal aging and in Alzheimer’s disease: self-reports vs family reports. Gerontologist 1994;34:324–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sevush S Relationship between denial of memory deficit and dementia severity in Alzheimer disease. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol 1999;12:88–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clare L, Wilson BA. Longitudinal assessment of awareness in early-stage Alzheimer’s disease using comparable questionnaire-based and performance-based measures: a prospective one-year follow-up study. Aging Ment Health 2006;10:156–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clare L, Nelis SM, Martyr A, et al. Longitudinal trajectories of awareness in early-stage dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2012;26: 140–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sousa MF, Santos RL, Nogueira ML, et al. Awareness of disease is different for cognitive and functional aspects in mild Alzheimer’s disease: a one-year observation study. J Alzheimers Dis 2015;43: 905–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vogel A, Waldorff FB, Waldemar G. Longitudinal changes in awareness over 36 months in patients with mild Alzheimer’s disease. Int Psychogeriatr 2015;27:95–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson RS, Boyle PA, Yu L, et al. Temporal course and pathologic basis of unawareness of memory loss in dementia. Neurology 2015; 85:984–991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kalbe E, Salmon E, Perani D, et al. Anosognosia in very mild Alzheimer’s disease but not in mild cognitive impairment. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2005;19:349–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Galeone F, Pappalardo S, Chieffi S, et al. Anosognosia for memory deficit in amnestic mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2011;26:695–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Edmonds EC, Delano-Wood L, Galasko DR, et al. Subjective cognitive complaints contribute to misdiagnosis of mild cognitive impairment. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2014;20:836–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Therriault J, Ng KP, Pascoal TA, et al. Anosognosia predicts default mode network hypometabolism and clinical progression to dementia. Neurology 2018;13:e932–e939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cacciamani F, Tandetnik C, Gagliardi G, et al. Low cognitive awareness, but not complaint, is a good marker of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 2017;59:753–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vannini P, Amariglio R, Hanseeuw B, et al. Memory self-awareness in the preclinical and prodromal stages of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychologia 2017;99:343–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Farias ST, Mungas D, Reed BR, et al. The measurement of Everyday Cognition (ECog): scale development and psychometric properties. Neuropsychology 2008;22:531–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gerretsen P, Chung JK, Shah P, et al. Anosognosia is an independent predictor of conversion from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease and is associated with reduced brain metabolism. J Clin Psychiatry 2017;78:e1187–e1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hanseeuw BJ, Betensky RA, Mormino E, et al. PET staging of amyloidosis using striatum. Alzheimers Dement 2018;14:1281–1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clark CM, Pontecorvo MJ, Beach TG, et al. Cerebral PET with florbetapir compared with neuropathology at autopsy for detection of neuritic amyloid-beta plaques: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Neurol 2012;11:669–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hanseeuw BJ, Betensky RA, Jacobs HIL, et al. Association of amyloid and tau with cognition in preclinical Alzheimer disease: a longitudinal study. JAMA Neurol (in press). 10.1001/jamaneurol.20191424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hayes AF, Matthes J. Computational procedures for probing interactions in OLS and logistic regression: SPSS and SAS implementations. Behav Res Methods 2009;41:924–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaszniak AW, Edmonds EC. Anosognosia and Alzheimer’s disease: behavioral studies In: Prigatano GP, ed. The study of anosognosia. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2010:189–227. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roberts JL, Clare L, Woods RT. Subjective memory complaints and awareness of memory functioning in mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review. Dem Geriatr Cogn Disord 2009;28:95–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Starkstein SE. Anosognosia in Alzheimer’s disease: diagnosis, frequency, mechanism and clinical correlates. Cortex 2014;61:64–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tabert MH, Albert SM, Borukhova-Milov L, et al. Functional deficits in patients with mild cognitive impairment: prediction of AD. Neurology 2002;58:758–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marshall G, Kaufer DI, Lopez OL, et al. Right subiculum amyloid plaque density correlates with anosognosia in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2004;75:1396–1400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salmon E, Perani D, Herholz K, et al. Neural correlates of anosognosia for cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease. Hum Brain Mapp 2006;27:588–597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Northoff G, Bermpohl F. Cortical midline structures and the self. Trends Cogn Science 2004;8:102–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Northoff G, Heinzel A, de Greck M, et al. Self-referential processing in our brain: a meta-analysis of imaging studies on the self. Neuroimage 2006;31:440–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sánchez-Benavides G, Grau-Rivera O, Cacciaglia R, et al. Distinct cognitive and brain morphological features in healthy subjects unaware of informant-reported cognitive decline. J Alzheimers Dis 2018;65:181–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vannini P, Hanseeuw B, Munro CE, et al. Hippocampal hypometabolism in older adults with memory complaints and increased amyloid burden. Neurology 2017;88:1759–1767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Monahan PO, Boustani MA, Alder CA, et al. Practical clinical tool to monitor dementia symptoms: the HABC-Monitor. Clin Interv Aging 2012;7:143–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Starkstein SE, Jorge R, Mizrahi R, Robinson RG. A diagnostic formulation for anosognosia in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2006;77:719–725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Merema MR, Speelman CP, Foster JK, Kaczmarek EA. Neuroticism (not depressive symptoms) predicts memory complaints in some community-dwelling older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2013;21: 729–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zlatar ZZ, Moore RC, Palmer BW, et al. Cognitive complaints correlate with depression rather than concurrent objective cognitive impairment in the successful aging evaluation baseline sample. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2014;27:181–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tardy M, Gonthier R, Barthelemy JC, et al. Subjective sleep and cognitive complaints in 65 year old subjects: a significant association. The PROOF cohort. J Nutr Health Aging 2015;19:424–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]