Abstract

In 2015, Congress passed the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA), a policy intended to transition Medicare away from pure fee-for-service care to value-based care. MACRA does this by evaluating the cost and quality of providers, resulting in financial bonuses and penalties in Medicare reimbursement. MACRA offers two tracks for participation, the Merit-based Incentive Payment System and the Advanced Alternative Payment Models. Although the payment rules are different for each of the tracks, common to both is an emphasis on holding providers accountable for high-quality, cost-efficient care. Early data suggest that the End-stage renal disease Seamless Care Organizations, an Advanced Alternative Payment Model, resulted in cost-savings concurrent with improved care quality. Additionally, on July 10th 2019, the President signed an executive order that further attempts to improve kidney disease care by shifting its focus away from in-center hemodialysis and towards chronic kidney disease care, home-based dialysis, kidney transplantation, and innovating new therapies for kidney disease. These changes to nephrology reimbursement present a unique opportunity to improve patient outcomes in a cost-effective way. A multidisciplinary effort among policy makers, nephrology providers, and patient advocacy groups is critical to ensure these changes in care delivery safeguard and improve patient health.

INTRODUCTION

Total healthcare expenditures in the United States (US) were $3.5 trillion in 2017 and are projected to reach nearly $6.0 trillion by 2027. Medicare accounted for $705.9 billion in 2017.1 While healthcare costs in the US outstrip other developed countries, health outcomes continue to lag, raising the question of how to increase the value of healthcare in the US.2

A major contributor to increased health spending is fee for service (FFS), when providers are reimbursed for the quantity of services provided.2-6 Because FFS rewards increased spending independent of health outcomes, patients might receive excess services that yield little benefit or even harm. A recent study of Medicare FFS care in hospitalized patients found high variation in physician spending, but no difference in 30-day mortality or other outcomes between more expensive and cheaper providers.7 FFS in dialysis likely contributed to the overuse of erythropoietin, despite numerous randomized trials showing harm from excessive erythropoietin use.8-13 After the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) established the end-stage renal disease (ESRD) prospective payment system (PPS) and ESRD Quality Incentive Program (QIP)—bundling injectable medications into a single dialysis payment and coupling payments to quality measures—, erythropoietin use dropped dramatically with concurrent decreases in death, strokes, and heart attacks.14

In 1997, the US government passed the Sustained Growth Rate (SGR), mandating strict caps on the growth of Medicare’s payments to physicians. However, Medicare spending continued to outpace projected growth. Unsurprisingly, the SGR became the perennial target of physician and patient advocacy groups, and the government repeatedly postponed the SGR’s cuts.15,16

Congress eventually replaced the defunct SGR with the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA) (House: 392–37, Senate: 92–8).17 In contrast to the SGR, MACRA focuses on financially rewarding providers who deliver high-quality, cost-effective care and penalizing those who do not.18 A key component of MACRA is its emphasis on holding providers accountable for the downstream consequences of their healthcare decisions, including adverse events and expensive complications. Consequently, MACRA encourages physicians to coordinate care with other high-value providers.19

MACRA OVERVIEW AND PARTICIPATION

The vast majority of Medicare providers are required to participate in one of two MACRA tracks, the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) or an Advanced Alternative Payment Model (Advanced APM) (Table 1).20 Although both tracks have different requirements, they share similar priorities by evaluating providers on cost and quality. Because of the stringent requirements of advanced APMs, most providers and nephrologists have enrolled in MIPS (91% in 2017).21

Table 1:

Comparing the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System to Advanced Alternative Payment Models

| Merit-Based Incentive Payment System | Advanced Alternative Payment Model |

|

|---|---|---|

| Eligibility |

|

|

| Incentives and Penalties | Payments up- and downward adjusted using a composite performance score:

|

|

| Fee Schedule Update (after 2026) |

|

|

Notes: Adapted from data from Matousek, et al, 2016.53 Abbreviations: EHR = electronic health record, MIPS = Merit-based Incentive Payment System.

CMS allows providers to participate as individuals or as groups within the same tax identification number (TIN). Reporting as a group allows providers to “pool risk,” mitigating the impact of high-cost or low-quality outliers. However, providers and provider groups with low volumes of Medicare patients or services face disadvantages because they cannot achieve the same economies of scale as large provider groups. CMS provides two avenues to protect small-volume providers. First, providers must meet Medicare volume and cost thresholds for MACRA eligibility. Second, in 2018, CMS began allowing small provider groups with 10 or fewer clinicians to report as “virtual groups.” Virtual groups allow group-level reporting without requiring a formal merger into a single financial organization. Once providers form a virtual group, they cannot exit the group for the duration of the performance period.

THE MERIT-BASED INCENTIVE PAYMENT SYSTEM (MIPS)

The Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) is the mainstay of MACRA, with most Medicare providers enrolling in the program.21 In contrast to other Medicare value-based purchasing programs, the MIPS compares providers to their peers instead of national benchmarks by compiling 100-point performance scores weighted across 4 categories: quality, cost, improvement activities, and promoting interoperability.22 MACRA varies the categories’ respective weights year to year to allow providers to adapt to the MIPS’s more unfamiliar parts (Table 2). The cost category carried 0% weight in 2017, which will progressively increase to 30% by 2022. The MIPS follows a 3-year review cycle: a performance year where a provider submits MIPS data, a feedback year, and a payment year when positive and negative payment adjustments are applied to claims processed two years after the performance year.

Table 2:

Changes to the Merit-based Incentive Payment System and Advanced Alternative Payment Models over Time

| MERIT-BASED INCENTIVE PAYMENT SYSTEM |

2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composite Score Weights * | |||||

| - Quality | 50% | 45% | 40% | 35% | 30% |

| - Cost | 10% | 15% | 20% | 25% | 30% |

| - Improvement Activities | 15% | 15% | 15% | 15% | 15% |

| - Promoting Interoperability | 25% | 25% | 25% | 25% | 25% |

| Payment Adjustments † | - | ± 4% | ± 5% | ± 7% | ± 9% |

| ADVANCED ALTERNATIVE PAYMENT MODELS |

2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022+ |

| Required Risk Thresholds § | |||||

| - % of Medicare Payments | 25% | 50% | 50% | 75% | 75% |

| - % of Medicare Patients | 20% | 35% | 35% | 50% | 50% |

Notes:

Composite score weights for the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System for each corresponding performance year

Payment adjustment amounts are listed for payment years (2 years after the performance year). Payment adjustments for the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System were not relevant for payment year 2018.

Required risk thresholds for a provider to qualify as an Advanced Alternative Payment Model. Specifically, the proportion of a provider’s Medicare Part B payments and Medicare Part B patients seen through the Alternative Payment Model must exceed the threshold for the corresponding performance year.

The Quality metric requires providers to select six specialty specific measures from over 270 quality measures. When a specialty has fewer than six available quality measures, all must be reported. Some measures such as depression screening span multiple specialties including nephrology. One measure must evaluate an “outcome,” or must be a designated high priority measure if an outcome measure is not available. Multi-specialty providers reporting as a group may choose six quality measures and two outcomes measures among any of the available measures for the specialties within the practice.

Although nephrologists officially have 15 available quality measures and one outcome measure, most are not truly nephrology specific, such as Zoster vaccination and screening for future fall risk, underscoring the need to create additional evidence-based nephrology measures (Table 3). Nephrology specific measures include timely referral to hospice for patients with ESRD who have withdrawn from dialysis and documenting an adequate follow-up plan for patients with high blood pressure.23 The nephrology outcome measure is the percentage of adult prevalent patients with ESRD on hemodialysis using a dialysis catheter. Finally, nephrologists may also opt into a quality metric registry, such as one provided by the Renal Physicians Association,24 which contains ten custom measures for 2019, including use of an ACE inhibitor or ARB and timely transplantation referral.

Table 3:

Merit-Based Incentive Payment System and ESRD Seamless Care Organization Quality Measure Sets

| Measure Sets | Measure Type |

High Priority |

|---|---|---|

| MERIT-BASED INCENTIVE PAYMENT SYSTEM MEASURES | ||

| Diabetes: Hemoglobin A1c Poor Control (>9%) | Intermediate Outcome | Yes |

| Pediatric Kidney Disease: ESRD patients Receiving Dialysis: Hemoglobin Level < 10g/dL | Intermediate Outcome | Yes |

| Medication Reconciliation Post-Discharge | Process | Yes |

| Advance Care Plan | Process | Yes |

| Documentation of Current Medications in the Medical Record | Process | Yes |

| Functional Outcome Assessment | Process | Yes |

| Falls: Screening for Future Fall Risk | Process | Yes |

| Adult Kidney Disease: Catheter Use for Greater Than or Equal to 90 Days | Outcome | Yes |

| Adult Kidney Disease: Referral to Hospice | Process | Yes |

| Preventive Care and Screening: Screening for High Blood Pressure and Follow-Up Documented | Process | No |

| One-Time Screening for Hepatitis C Virus for Patients at Risk | Process | No |

| Zoster (Shingles) Vaccination | Process | No |

| Preventive Care and Screening: Influenza Immunization | Process | No |

| Pneumococcal Vaccination Status for Older Adults | Process | No |

| Diabetes: Medical Attention for Nephropathy | Process | No |

| ESRD Seamless Care Organization Measures | ||

| Hemodialysis Vascular Access: Maximizing Placement of Arterial Venous Fistulas | QIP Process | |

| Hemodialysis Vascular Access: Minimizing Use of Catheters | QIP Process | |

| Bloodstream Infections in Hemodialysis Outpatients | QIP Outcome | |

| Hemodialysis Adequacy: Minimum Delivered Hemodialysis Dose | QIP Outcome | |

| Proportion of Patients with Hypercalcemia | QIP Outcome | |

| Peritoneal Dialysis Adequacy: Delivered Dose of Peritoneal Dialysis Above Minimum | QIP Outcome | |

| In-Center Hemodialysis Consumer Assessment of Health Care Providers and Systems Survey | QIP Outcome | |

| Kidney Disease Quality of Life Survey | Outcome | |

| ESCO Standardized Hospitalization Ratio for Admissions | Outcome | |

| ESCO Standardized Mortality Ratio | Outcome | |

| ESCO Standardized Readmission Ratio | Outcome | |

| Documentation of Current Medications in the Medical Record | Process | |

| Falls: Screening, Risk Assessment, and Plan of Care to Prevent Future Falls | Process | |

| Advance Care Plan | Process | |

| Medication Reconciliation Post Discharge | Process | |

| Diabetes Care: Eye Exam | Process | |

| Diabetes Care: Foot Exam | Process | |

| Influenza Immunization for the ESRD Population | Process | |

| Pneumonia Vaccination Status | Process | |

| Screening for Clinical Depression and Follow-up Plan | Process | |

| Tobacco Use: Screening and Cessation Intervention | Process |

Notes: Abbreviations: ESRD = end-stage renal disease, QIP = quality incentive program, ESCO = ESRD seamless care organization

The Cost category incentivizes cost-efficient care. Quality metrics without counterbalancing cost measures could encourage providers to overtreat patients with high-cost care. Conversely, cost measures without quality measures could incentivize the skimping of necessary medical services. CMS does not require data submission for the cost measure and instead calculates it using claims.22

Cost measures fall into two categories, “all-cost” measures and “episode-based” measures. All-cost measures hold providers accountable for all Medicare Parts A and B spending within a period of time, irrespective of the clinical reason or the provider responsible for the service. Episode-based measures account for “clinical relatedness,” holding providers accountable only for services deemed related to the index service. Both types of measures hold providers responsible for costs billed by other providers to incentivize judicious use of referrals, effective care transitions, and care coordination.

The all-cost measures are the Medicare Spending per Beneficiary (MSPB) and the Total Per Capita Cost (TPCC) measures.25 The MSPB measure attributes all Medicare Parts A and B spending from 3 days prior to an index hospitalization to 30 days after hospital discharge to the clinician billing the plurality of Part B claims during the index hospitalization. Nephrologists may be attributed the MSPB measure if the billed Part B dialysis procedures constitute the plurality of Part B costs. The TPCC measure attributes all Medicare Parts A and B spending in the entire year to the provider billing the plurality of outpatient evaluation and management services for the year. After risk-adjusting costs for clinical and patient characteristics, providers are compared against their peers. Because the TPCC is intended to assess the costs of primary care providers that bill the majority of evaluation and management services, CMS explicitly excludes certain subspecialists (generally procedural ones) from the measure. However, nephrologists are not excluded and thus could be attributed the TPCC measure.26,27

CMS has already developed, and is developing, episode-based cost measures that focus on costs clinically relevant to the episode and reasonably within the attributed provider’s influence. For instance, the recently finalized acute kidney injury (AKI) requiring new inpatient dialysis episode includes subsequent outpatient dialysis costs, chronic kidney disease care, and readmissions for volume overload, but excludes unrelated costs such as elective surgeries.28 The all-cost measures, on the other hand, include all services including elective surgeries. After risk-adjusting episode costs, providers are compared with their peers. CMS has recruited multi-specialty provider committees (including representatives from the American Society of Nephrology and the Renal Physicians of America) to advise in episode construction.

The MIPS adopted eight episodes for performance year 2019, and finalized an additional ten for performance year 2020.29,30 Two episodes relevant to nephrology are “AKI requiring new inpatient dialysis” and “Hemodialysis Access Creation.”31,32 The AKI episode begins with an inpatient stay for AKI requiring dialysis and includes subsequent outpatient dialysis, CKD care, and anemia management. The episode excludes inpatient plasmapheresis and dialysis for drug overdose/poisoning, kidney transplant, and ESRD.29,31 The Hemodialysis Access Creation episode focuses on arteriovenous fistula or graft placement and relevant services, including preoperative workup, perioperative care, wound or vascular complications, dialysis catheter-related bloodstream infections, and surgical revisions.29,32

Because most of the variability of these cost measures comes from downstream complications such as readmissions, the measures are intended to enhance care coordination and encourage preventing complications. For instance, high-performing inpatient providers attributed an AKI episode will need to coordinate care with outpatient dialysis centers and will also refer their patients to other cost-conscious providers. The success of these measures depends on robust risk-adjustment to ensure providers are not penalized for taking care of sicker patients prone to developing complications. Otherwise, providers may be encouraged to cherry-pick healthier patients. It will be important to monitor that vulnerable patients do not face difficulty in accessing high-quality care.

The last two MIPS categories grade providers on their organization practices. The Improvement Activity Score assesses participation in improvement activities, such as follow-up on patient experience and completion of antibiotic stewardship training.33 The Promoting Interoperability category requires that providers implement a robust electronic health record (EHR) that includes e-prescribing, providing patient access, security risk analysis, and sending summaries of care.

The MIPS replaces many of the previous metrics for evaluating providers and compiles them into a final MIPS Score used for payment adjustment. Currently, the MIPS emphasizes participation over performance, with only 5% of clinicians receiving negative adjustments. As providers become accustomed to MIPS scoring, including the increasingly important cost measure, CMS will begin shifting the emphasis of MIPS towards performance, with more providers receiving negative payment adjustments. Negative payment adjustments were up to 4% in 2019 and are projected to increase to 9% by 2022 (Table 2).

ADVANCED ALTERNATIVE PAYMENT MODELS (ADVANCED APMs)

The Advanced Alternative Payment Model (Advanced APM) track incentivizes delivering high-value care above and beyond the requirements established by MIPS.34 In exchange for meeting these stringent requirements, CMS gives advanced APMs a 5% lump-sum bonus and exempts them from the MIPS. To achieve these benchmarks, most advanced APMs focus heavily on care-coordination and comprehensive care. Many of these payment models were established by CMS’s Innovation Center, predated MACRA, and focused on primary care and large, multi-specialty groups through Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs). In addition to incorporating these models into the advanced APM track, CMS has created additional models spanning a wide range of specialties and disease areas.

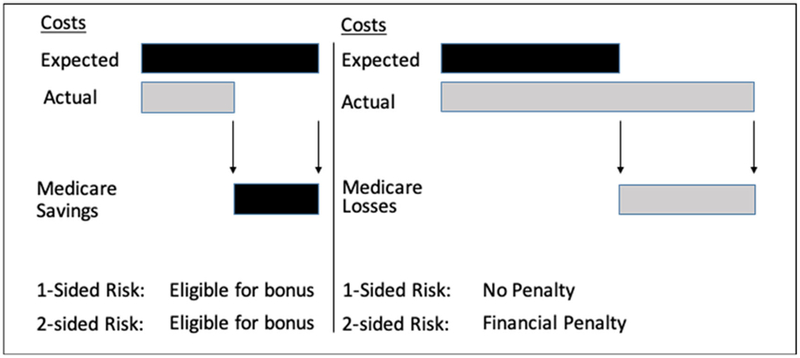

Although each model has different structures and standards, the mainstay of an advanced APM is taking on more than nominal financial risk.18,35 CMS does this by calculating each provider’s estimated savings or losses to Medicare, defined as the difference between the provider’s observed costs and risk-adjusted expected costs, which are usually calculated using data from traditional Medicare Parts A and B (Figure 1). In one-sided risk models, providers receive a portion of Medicare savings but incur no penalty from Medicare losses. Providers accepting two-sided risk must pay Medicare back a percentage of any losses as well as sharing in savings. In general, CMS requires that advanced APMs take on increasing amounts of two-sided risk over time (Table 2). Provider groups unable to meet financial risk requirements are known as regular APMs. Regular APMs taking on one-sided risk are not exempt from MIPS and do not receive the 5% lump sum bonus but are still eligible for shared savings.

Figure 1: Calculating shared-savings and losses under 1- and 2-sided risk models.

In the left panel, the provider’s actual costs are less than expected cost, leading to Medicare savings. The right panel conversely depicts Medicare losses, when actual costs exceed expected costs. One-sided and two-sided risk models are eligible for bonuses with Medicare savings, but only two-sided risk models are liable with Medicare losses.

In addition to taking on financial risk, all APMs (regular and advanced) must meet a battery of quality measures.34 Unlike in MIPS, quality measures are dictated by CMS and cannot be elected. To ensure that providers do not cut necessary care to maximize shared savings, CMS requires that providers forfeit any shared savings if providers do not meet minimum quality requirements.

The performance of advanced APMs has been, on net, positive. In 2017, the CMS reported a total of $1.1 billion in savings, with $780 million shared with the 60% of ACOs posting savings to Medicare.36 While these savings were relatively modest compared to overall Medicare spending, some studies suggest indirect savings to Medicare due to spillover effects on fee-for-service Medicare spending (an additional $1.8-$4.2 billion in 2016).37,38 The National Association of ACOs calculated that ACOs saved CMS more than $1.8 billion from 2013 to 2015.39 ACOs also achieved higher average quality scores compared to fee-for-service medical group practices. From 2013 to 2016, their quality scores were higher by 15 percent on average.37

NEPHROLOGY-FOCUSED APMS

The main nephrology-focused APM is the Comprehensive ESRD Care Model, which currently has 36 participating provider groups, known as ESRD Seamless Care organizations (ESCOs).40 ESCOs act as ACOs for patients with ESRD and focus on improving care-coordination and care delivery.40 To achieve these goals, ESCOs establish financial partnerships among dialysis facilities, nephrologists, vascular surgeons, interventional radiologists, and other providers including cardiologists and endocrinologists. Although most ESCOs are affiliated with the large dialysis organizations (LDOs), non-LDOs including independently owned dialysis facilities and hospital-based dialysis facilities have also participated. The LDO-based ESCOs must hold two-sided risk, while the non-LDOs may hold one-sided risk. However, to qualify as an advanced APM an ESCO must take on two-sided risk. As with all APMs, ESCOs are evaluated on a strict set of quality measures, which include all ESRD Quality Incentive Program (QIP) measures (Table 3).

An evaluation of the first ESCO performance year (10/1/2015–12/31/2016) demonstrated $29.9 million in Medicare Parts A and B cost-savings alongside improved care quality.40 Most cost savings came from decreased acute inpatient and post-acute care spending, with a 6% lower likelihood of hospitalization. The overall cost of outpatient dialysis increased, $12 per patient per month, suggesting that providers succeeded in substituting expensive inpatient spending with cheaper outpatient care and greater dialysis adherence. Patients receiving dialysis in ESCOs had lower dialysis catheter use, fewer hospitalizations associated with ESRD, and fewer vascular access complications. Patients did not report a statistically significant or clinically meaningful change in quality of life as measured by five quality of life composite measures in the Kidney Disease and Quality of Life (KDQOL-36) survey.41

FUTURE PAYMENT MODELS RELEVANT TO NEPHROLOGY

In the last couple of years, nephrology societies have proposed payment models aimed at shifting the emphasis in the US away from dialysis care to the full spectrum of kidney care. The Renal Physicians’ Association proposed a model focused on improving upstream preparation for dialysis, including shared decision-making, access to transplant, and a healthy transition to dialysis.42 The National Kidney Foundation has also developed a model (“the CKD-Intercept model”) that emphasized early CKD detection, effective care-coordination, prevention of hospitalizations and readmissions, and CKD patient education through partnerships between primary care providers and nephrologists.43 Additionally, the American Society of Nephrology outlined a comprehensive kidney care model that aimed to address discontinuities in care across advanced kidney disease, kidney failure/dialysis, and transplantation.44

While none of these models have been formally implemented, these efforts helped push the government to decrease its emphasis on in-center hemodialysis. On July 2019, the President signed an executive order prioritizing policies that “transform care delivery for patients with chronic kidney disease.”45 The initiative has three main goals: reduce the prevalence of ESRD through slowing CKD progression, increase the use of transplant and home dialysis, and encourage innovation of new kidney therapies. With this initiative comes new CMS Innovation Center payment models aimed at promoting these goals: the ESRD Treatment Choice (ETC) model, the Kidney Care First (KCF) model and the Comprehensive Kidney Care Contracting (CKCC) model, the latter of which has three accountability tracks.46

The ETC model is a mandatory payment model incentivizing increased use of home dialysis and kidney transplants and, according to the proposed rule, will run January 1, 2020, to June 30, 2026.47 Unlike other Innovation Center models, the ETC model applies to all providers including MIPS and Advanced APM providers managing patients with ESRD. The ETC model will adjust dialysis facility payments (for dialysis facilities) and Monthly Capitation Payments (MCP, for nephrologists) by rewarding providers who successfully increase the use of transplant and home dialysis.

The ETC incorporates two payment adjustments.48 The first is a uniformly positive adjustment for Medicare home dialysis treatment claims and home dialysis MCP claims during the initial three years of the model. The second adjustment will upward- and downward-adjust all dialysis and MCP claim payments (including in-center hemodialysis claims) based on the providers’ home dialysis and transplant rates. Providers’ performance will be judged relative to their peers, with home dialysis and transplantation rates risk-adjusted for age and comorbidities. Payment adjustments will increase over the model duration, with nephrologists and dialysis facilities holding more financial risk over time. The model acts in concert with other dialysis payment adjustors, including the Quality Incentive Program (QIP), MIPS adjustments, and advanced APM shared-savings and losses. The ETC excludes beneficiaries under age 18, in hospice, diagnosed with dementia, or receiving dialysis for acute kidney injury and also excludes low-volume providers that may be vulnerable to outliers.

To evaluate the ETC Model’s effectiveness as a policy, CMS will implement the model in a randomized fashion at the hospital referral region level.48 Thus, even though the model is mandatory, payment adjustments will only apply to providers in regions randomized to the intervention arm. In addition to evaluating the effects of the ETC model on home dialysis and transplant, the randomization will potentially allow CMS to evaluate the ETC’s impact on Medicare program spending and adverse events such as mortality and hospitalizations.

The Kidney Care First (KCF) and Comprehensive Kidney Care Contracting (CKCC) Models are voluntary payment models that build upon the ESCO structure.49 The main goal is to incentivize delayed progression to ESRD in patients with CKD stage 4 and 5, optimize the transition to ESRD, promote early kidney transplantation, and optimize care for post-transplantation beneficiaries. These models are adapted from the Primary Care First and Direct Contracting models for primary care providers,49 and are scheduled for implementation from January 1, 2020, through December 31, 2023 with the possibility of one or two additional years.

The KCF model is available only to nephrology practices and nephrologists.49,50 In this model, providers will receive capitated payments for attributed beneficiaries with CKD stages 4 and 5 or with ESRD on dialysis. The payments are performance adjusted using quality and cost measures. Quality measures include the effectiveness of depression and blood pressure control, and cost measures include the number of suboptimal ESRD starts, hospitalization costs, and total per capita costs (modeled after the MIPS’ TPCC measure). Providers will also receive bonus payments for patients who receive a kidney transplant to be paid over three years following the transplant. By capitating payments, the KCF allows providers the flexibility to decide how to best coordinate patient care. For KCF providers to maintain financial viability, they will have to efficiently manage patients while reducing expensive complications such as unnecessary hospitalizations.

The CKCC model targets groups of health care providers caring for Medicare beneficiaries with CKD stage 4 or 5, ESRD on dialysis, or a kidney transplant and can include dialysis providers.49 These provider groups are similar to ESCOs in that they represent financial partnerships among multidisciplinary groups of providers, including nephrologists, transplant physicians, dialysis facilities, and other healthcare providers. As with the KCF model, groups will receive adjusted capitated payments for managing patients with kidney disease and will also receive kidney transplant bonus payments.

Providers participating in the CKCC model are intended to function as ACOs in the same vein as the ESCOs, with providers taking on financial risk based on total Medicare Part A and B spending.49 In fact, CKCCs will replace ESCOs as the risk-bearing model available to dialysis facilities. Prior research suggests that multidisciplinary care models in CKD could be cost-effective in a Medicare population.51 The CKCC model has three accountability tracks. The CKCC Graduated Model begins with a lower-reward one-sided model, and incrementally phases in greater downside risk alongside greater potential reward. The CKCC Professional Model gives providers the opportunity to earn 50% of shared savings in exchange for taking on 50% of shared Medicare losses. Finally, the CKCC Global Model requires that providers take on 100% two-sided risk for the total cost of all Parts A and B services.

The KCF, CKCC Professional, and CKCC Global models will qualify as Advanced APMs beginning in 2021,49 with participation starting in 2020 and financial accountability in 2021. CMS has released a request for application for these models, with the deadline for application January 22, 2020.50 Because providers who are accepted into the model will have the option to withdraw by late 2020 without penalty, providers who are still weighing their options should still submit applications to CMS.

IMPLICATIONS FOR NEPHROLOGY

MACRA provides a uniquely challenging, dynamic, but potentially promising landscape for the nephrology community. By increasing its emphasis on reimbursing for value, CMS has financially encouraged providers to demonstrate that their actions maintain care quality in a cost-efficient manner. To ensure that patients with chronic kidney disease and ESRD are not harmed and truly benefit from MACRA, it is imperative that these payment models reward providers for effectively promoting patient health, including improved care coordination, dialysis education, and prevention of adverse events such as avoidable hospitalizations. It is also important that the new models are not detrimental to patients and that patients maintain access to high-quality dialysis care. Adequate risk-adjustment, selection of effective quality and cost metrics, and fair attribution are all vital to the success of MACRA and patient health.

Since most providers will participate in MACRA through the MIPS, new nephrology metrics must be constructed carefully. The first year’s performance results for MIPS eligible clinicians had 95% of clinicians meeting neutral or positive adjustment thresholds.52 In future years, higher proportions of providers will face financial penalties. We recommend that the nephrology community continue to embrace an active role in helping to shape new payment measures, including the construction of new episode groups relevant to nephrology.

With the President’s executive order on “Advancing American Kidney Care,” much of the community’s attention has focused on new payment models. These models will introduce new incentives to transform the focus of kidney disease away from in-center dialysis and toward other therapies that are cheaper, more effective, and more patient-centric, including the prevention of CKD progression, increased use of home dialysis, and promotion of kidney transplant. Given the extraordinary cost of in-center dialysis and the morbidity and mortality associated with the treatment, this effort should be lauded. The voluntary payment models, in particular, have the potential to shift the emphasis of kidney care away from in-center dialysis and towards a more holistic approach to treating kidney disease. Although many nephrologists and small dialysis providers might find it difficult to take on the required financial risk, if they are enrolled into the ETC (the mandatory model), it may be advantageous to participate in the voluntary models, given the aligned payment incentives.

CMS has also taken steps to evaluate the impact of these policies. For instance, CMS has chosen to implement the ETC in a randomized fashion, which may ease accurate assessment of the policy, though a clean evaluation may prove difficult if many providers in the control arm opt into the voluntary models. These policies will dramatically alter the organization of nephrology care in the near future, with large-scale changes in the supply and delivery of CKD care, dialysis, and transplant. The Administration’s goal to shift 80% of ESRD therapy to home modalities and transplant is incredibly ambitious, and the nephrology community and CMS should vigilantly monitor this initiative for negative and unintended impacts to patients.

In summary, MACRA presents a unique opportunity for transforming kidney disease care in the United States. A multidisciplinary effort among policy makers, nephrology providers, and patient advocacy is critical to safeguard and improve patient health in a cost-efficient manner.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) through the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK): EL receives support from NIDDK K08DK118213. EL also receives support from the University Kidney Research Organization. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Some of the data reported here have been supplied by the United States Renal Data System (USRDS). The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the author(s) and in no way should be seen as an official policy or interpretation of the U.S. government.

EL has a limited consultancy with Acumen, LLC. He helped moderate the “Acute Kidney Injury Requiring New Outpatient Dialysis” and the “Hemodialysis Access Creation” episode-based cost measures. SB is chair of the clinical subcommittee for the “Acute Kidney Injury Requiring New Outpatient Dialysis” episode-based cost measure. SB is a medical director at the Northwest Kidney Centers which provides salary support.

Grant support: EL receives support from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK): NIDDK K08DK118213.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: EL has a limited consultancy with Acumen, LLC. SB is a medical director at the Northwest Kidney Centers.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kamal R, Cox C, McDermott D, Ramirez M, Sawyer B. U.S. health system is performing better, though still lagging behind other countries. Peterson-Kais Health Syst Tracker. March 2019. https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/brief/u-s-health-system-is-performing-better-though-still-lagging-behind-other-countries/. Accessed April 5, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bodenheimer T. High and rising health care costs. Part 1: seeking an explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(10):847–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glied S Health Care Costs: On the Rise Again. J Econ Perspect. 2003;17(2):125–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mongan JJ, Ferris TG, Lee TH. Options for slowing the growth of health care costs. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(14):1509–1514. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb0707912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Orszag PR, Ellis P. The challenge of rising health care costs--a view from the Congressional Budget Office. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(18):1793–1795. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp078190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fernandopulle R Breaking The Fee-For-Service Addiction: Let’s Move To A Comprehensive Primary Care Payment Model ∣ Health Affairs. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20150817.049985/full/. Published August 17, 2015. Accessed April 24, 2019.

- 7.Tsugawa Y, Jha AK, Newhouse JP, Zaslavsky AM, Jena AB. Variation in Physician Spending and Association With Patient Outcomes. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(5):675–682. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Phrommintikul A, Haas SJ, Elsik M, Krum H. Mortality and target haemoglobin concentrations in anaemic patients with chronic kidney disease treated with erythropoietin: a meta-analysis. Lancet Lond Engl. 2007;369(9559):381–388. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60194-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh AK, Szczech L, Tang KL, et al. Correction of anemia with epoetin alfa in chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(20):2085–2098. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Di Lullo L, Floccari F, Granata A, Malaguti M. Low-Dose Treatment with Erythropoiesis-Stimulating Agents and Cardiovascular Geometry in Chronic Kidney Disease: Is Darbepoetin-α More Effective than Expected? Cardiorenal Med. 2012;2(1):18–25. doi: 10.1159/000334942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drüeke TB, Locatelli F, Clyne N, et al. Normalization of hemoglobin level in patients with chronic kidney disease and anemia. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(20):2071–2084. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collins AJ, Ebben JP, Gilbertson DT. EPO Adjustments in Patients With Elevated Hemoglobin Levels: Provider Practice Patterns Compared With Recommended Practice Guidelines. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;49(1):135–142. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.09.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pfeffer MA, Burdmann EA, Chen C-Y, et al. A Trial of Darbepoetin Alfa in Type 2 Diabetes and Chronic Kidney Disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(21):2019–2032. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chertow GM, Liu J, Monda KL, et al. Epoetin Alfa and Outcomes in Dialysis amid Regulatory and Payment Reform. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27(10):3129–3138. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015111232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.111th Congress. Temporary Extension Act of 2010.; 2010:Page 124 STAT. 42. https://www.congress.gov/bill/111th-congress/house-bill/4691/text. Accessed August 2, 2019.

- 16.112th Congress. American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012.; 2013:Page 126 STAT. 2313. https://www.congress.gov/bill/112th-congress/house-bill/8/text?overview=closed&r=1. Accessed July 29, 2019.

- 17.114th Congress. Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015.; 2015:Page 129 STAT. 87. https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/2/text. Accessed July 10, 2019.

- 18.Lin E, MaCurdy T, Bhattacharya J. The Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act: Implications for Nephrology. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28(9):2590–2596. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2017040407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hodgin S Value-based Care vs Fee-for-Service. http://www.insight-txcin.org/post/value-based-care-vs-fee-for-service. Published January 12, 2018. Accessed March 28, 2019.

- 20.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. MACRA: MIPS & APMs. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/quality-initiatives-patient-assessment-instruments/value-based-programs/macra-mips-and-apms/macra-mips-and-apms.html. Published June 14, 2019. Accessed July 10, 2019.

- 21.LaPointe J 91% of Eligible Clinicians Participated in 2017 MIPS Reporting. RevCycleIntelligence. https://revcycleintelligence.com/news/91-of-eligible-clinicians-participated-in-2017-mips-reporting. Published May 31, 2018. Accessed July 10, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Program; Revisions to Payment Policies Under the Physician Fee Schedule and Other Revisions to Part B for CY 2019; Medicare Shared Savings Program Requirements; Quality Payment Program; Medicaid Promoting Interoperability Program; Quality Payment Program-Extreme and Uncontrollable Circumstance Policy for the 2019 MIPS Payment Year; Provisions From the Medicare Shared Savings Program-Accountable Care Organizations-Pathways to Success; and Expanding the Use of Telehealth Services for the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder Under the Substance Use-Disorder Prevention That Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment (SUPPORT) for Patients and Communities Act. CMS-1963-F. Federal Register; 2018; 83(226): 59452–60303. Online. Available. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2018-11-23/pdf/2018-24170.pdf. Accessed 8/2/2019. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2019 Quality Payment Program (QPP) Measure Specification and Measure Flow Guide for MIPS Clinical Quality Measures (CQMs). Online. Available. November 2018. https://qpp.cms.gov/resource/2019%20Clinical%20Quality%20Measure%20Specifications%20and%20Supporting%20Documents. Accessed August 2, 2019.

- 24.Fischer MJ, Palevsky PM. Performance Measurement and the Kidney Quality Improvement Registry. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. June 2019:CJN.03180319. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03180319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2019 Cost Measure Information Forms. 2019. Online. Available. https://qpp.cms.gov/resource/2019%20Cost%20Measure%20Information%20Forms. Accessed 8/2/2019.

- 26.Healthmonix. 2020 Cost Measure #002: Total Per Capita Costs (TPCC). 2019. Online. Available. http://healthmonix.com/mips_cost_measures/2020-cost-measure-002-total-per-capita-costs-tpcc/. Accessed: 11/29/2019.

- 27.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Revised Total Per Capita Cost Measure Code List. March 2019. Online. Available. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs/2019-revised-TPCC-measure-specs.zip. Accessed: 11/29/2019.

- 28.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Acute Kidney Injury Requiring New Inpatient Dialysis Measure Codes List. April 2019. Online. Available. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs/2019-revised-ebcm-measure-specs.zip. Accessed: 11/29/2019/.

- 29.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. MACRA Feedback. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs/MACRA-Feedback.html. Published July 29, 2019. Accessed July 19, 2019.

- 30.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMS-1715-F and IFC. Medicare Program; CY 2020 Revisions to Payment Policies under the Physician Fee Schedule and Other Changes to Part B Payment Policies; Medicare Shared Savings Program Requirements; Medicaid Promoting Interoperability Program Requirements for Eligible Professionals; Establishment of an Ambulance Data Collection System; Updates to the Quality Payment Program; Medicare Enrollment of Opioid Treatment Programs and Enhancements to Provider Enrollment Regulations Concerning Improper Prescribing and Patient Harm; and Amendments to Physician Self-Referral Law Advisory Opinion Regulations Final Rule; and Coding and Payment for Evaluation and Management, Observation and Provision of Self-Administered Esketamine Interim Final Rule. November/15/2019. 84 FR 62568. Federal Register; Online. Available. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2019/11/15/2019-24086/medicare-program-cy-2020-revisions-to-payment-policies-under-the-physician-fee-schedule-and-other. Accessed: 11/29/2019. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Acute Kidney Injury Requiring New Inpatient Dialysis Measure - Cost Measure Methodology.; 2019. https://cmit.cms.gov/CMIT_public/ReportMeasure?measureRevisionId=2316. Accessed August 3, 2019.

- 32.Shireman PK, Woo K, Lipsitz EC. Hemodialysis access creation episode-based cost measure. J Vasc Surg. 2019;69(4):1322. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2019.01.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. MIPS: Explaining the Improvement Activities Performance Category. https://www.aafp.org/practice-management/payment/medicare-payment/mips/ia.html. Published February 2019. Accessed April 3, 2019.

- 34.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Alternative Payment Models (APMs) Overview. https://qpp.cms.gov/apms/overview. Published 2019. Accessed April 4, 2019.

- 35.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, The Lewin Group. Advanced APMs - QPP. https://qpp.cms.gov/apms/advanced-apms. Published 2019. Accessed April 24, 2019.

- 36.Castelluci M, Dickson V. Medicare ACOs saved CMS $314 million in 2017. Modern Healthcare. https://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20180830/NEWS/180839987/medicare-acos-saved-cms-314-million-in-2017. Published August 30, 2018. Accessed July 23, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mechanic R, Gaus C. Medicare Shared Savings Program Produces Substantial Savings: New Policies Should Promote ACO Growth ∣ Health Affairs. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20180906.711463/full/. Published September 11, 2018. Accessed July 23, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Program; Medicare Shared Savings Program; Accountable Care Organizations—Pathways to Success.; 2018. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2018-08-17/pdf/2018-17101.pdf. Accessed July 31, 2019.

- 39.Dobson A, Pal S, Hartzman A, Arzaluz L, Rhodes K, DaVanzo JE. Full Report for MSSP Savings 2012–2015. National Association ofo Accountable Care Organizations. https://www.naacos.com/full-report-for-mssp-savings-2012-2015. Published August 30, 2018. Accessed July 23, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 40.The Lewin Group. Comprehensive End Stage Renal Disease Care (CEC) Model - Performance Year 1 Annual Evaluation Report. October 2017. https://innovation.cms.gov/Files/reports/cec-annrpt-py1.pdf. Accessed August 2, 2019.

- 41.Peipert JD, Nair D, Klicko K, Schatell DR, Hays RD. Kidney Disease Quality of Life 36-Item Short Form Survey (KDQOL-36) Normative Values for the United States Dialysis Population and New Single Summary Score. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;30(4):654–663. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2018100994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Casale PN, Bailet J, Miller H. Preliminary Review Team Report to the Physician-Focused Payment Model Technical Advisory Committee (PTAC). https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/255906/RPAPreliminaryReviewTeamPRTReport.pdf. Published October 25, 2017. Accessed August 8, 2019.

- 43.National Kidney Foundation. CKDintercept. https://www.kidney.org/CKDintercept. Published June 30, 2015. Accessed June 17, 2019.

- 44.Meyer R ASN Care Delivery Model Concept: Comprehensive Care across a Patient’s Journey ∣ Kidney News. https://www.kidneynews.org/kidney-news/features/asn-care-delivery-model-concept-comprehensive-care-across-patient%E2%80%99s-journey. Published November 2018. Accessed November 27, 2019.

- 45.Department of Health and Human Services. HHS Launches President Trump’s ‘Advancing American Kidney Health’ Initiative. https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2019/07/10/hhs-launches-president-trump-advancing-american-kidney-health-initiative.html. Published July 10, 2019. Accessed July 19, 2019.

- 46.Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. HHS To Transform Care Delivery for Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/hhs-transform-care-delivery-patients-chronic-kidney-disease. Published July 10, 2019. Accessed July 19, 2019.

- 47.Department of Health and Human Services. Medicare Program; Specialty Care Models to Improve Quality of Care and Reduce Expenditures. July 2019. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/CMS-5527-P.pdf. Accessed August 2, 2019.

- 48.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Proposed End-Stage Renal Disease Treatment Choices (ETC) Mandatory Model. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/proposed-end-stage-renal-disease-treatment-choices-etc-mandatory-model. Published July 10, 2019. Accessed August 2, 2019.

- 49.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Kidney Care First (KCF) and Comprehensive Kidney Care Contracting (CKCC) Models ∣ CMS. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/kidney-care-first-kcf-and-comprehensive-kidney-care-contracting-ckcc-models. Published July 10, 2019. Accessed July 10, 2019.

- 50.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services: Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI). Kidney Care Choices (KCC) Model: Request for Application. 2019. Online. Available. https://innovation.cms.gov/Files/x/kcc-rfa.pdf. Accessed: 12/1/2019.

- 51.Lin E, Chertow GM, Yan B, Malcolm E, Goldhaber-Fiebert JD. Cost-effectiveness of multidisciplinary care in mild to moderate chronic kidney disease in the United States: A modeling study. Taal MW, ed. PLOS Med. 2018;15(3):e1002532. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Verma S Quality Payment Program (QPP) Year 1 Performance Results. https://www.cms.gov/blog/quality-payment-program-qpp-year-1-performance-results. Published November 8, 2018. Accessed July 19, 2019.

- 53.Matousek S What is MACRA Part 2: Digging into the Quality Payment Programs ∣ Day ∣ Health ∣ Strategies. July 2016. http://dayhealthstrategies.com/what-is-macra-part-2-digging-into-the-quality-payment-programs/. Accessed August 4, 2019.