Abstract

Personality traits such as conscientiousness and impulsivity correlate with temporal discounting, the degree to which individuals discount the value of future relative to present rewards. These variables have, in turn, been hypothesized to relate to income inequality in the United States. A key but untested assumption of this hypothesis is that the association among these variables is distinct across socioeconomic classes. The purpose of the present research is to test that assumption. N = 1,100 adults with annual income ranging from at or below the poverty line ($0-$20,000) to upper-middle class ($200,000+) completed personality measures and a measure of temporal discounting. The results of our preregistered analyses indicated a positive association of income with trait planfulness, and a negative association with trait impulsivity and one parameter of temporal discounting that captures a bias to prefer sooner rewards to a greater degree if they are delivered that day. Our results can inform psychological theories of inequality and a broader conversation about effective public policy.

Keywords: personality, temporal discounting, inequality, socioeconomic status

In his 1964 State of the Union Address, President Lyndon B. Johnson famously introduced a new legislative plan for the United States by boldly stating, “[t]his administration today, here and now, declares unconditional war on poverty in America.” Propelled by the national outcry against widening inequality in America by the Civil Rights and feminist movements of the 1960s, this address signaled the national recognition that systemic inequality was a problem that could not be alleviated without intervention from the highest level of government. President Johnson used this speech to present his plan for transforming the country into a “Great Society,” one in which poverty was eliminated and inequality was severely reduced. Now, over fifty years since Johnson’s historic declaration, data suggests that the United States remains an unequal society. Since 2013, the U.S. has had one of the highest rates of inequality among developed nations (OECD, 2018), and intergenerational analyses reveal trends of increased inequality and decreased class mobility for recent generations of Americans (Carr & Wiemers, 2016; Chetty et al., 2017). Finally, 12.7% of Americans – over 40 million people – were living below the poverty line as of 2016 (U.S. Census Bureau).

A critical question about the reality of inequality is whether and how the psychology of people living in difference socioeconomic classes might differ. Specifically, it is relevant to public policy to whether and how inequality relates to cognition and personality – both in reality and in commonly held lay theories. The present research seeks to establish whether individual differences in personality traits related to decision-making are related to socioeconomic class. The overarching aim of this line of work is to contribute to a broader conversation about finding solutions to reduce national inequality. Specifically, we hope that the patterns of relationships among our variables of interest may provide evidence-backed targets for safety net interventions.

Theories of How Inequality Relates to Decision-Making and Personality

Poverty is perhaps the most salient component of a society’s level of inequality. Those who are poor struggle to attain what are considered to be the basic necessities of food, housing, and clothing, while quality of life resources such as healthcare or higher education are often completely inaccessible. In a hierarchical social structure, those who live in poverty comprise the lowest socioeconomic class due to their lack of wealth or power over resources. Various theoretical models have offered predictions that individual differences in personality and decision-making are asymmetrical across socioeconomic class. We focus here on two that assume systematic differences in traits and decision-making preferences between those living above and below the poverty line. The first focuses on lay perceptions of poverty – how people think about people living in poverty – and the second on how and why people living in poverty actually make certain decisions.

The “just world” theory holds that people believe individuals deserve their place in the hierarchical social structure. In terms of lay attributions, this theory suggests that people assume that poverty is self-inflicted – presumably through attributes of the person such as traits, behaviors, and patterns of choice. Lerner (1980) describes this assumption as the (not necessarily accurate) belief that the world is fair and therefore that individuals are afforded prestige and power based on their personal qualities. This hypothesis predicts that beliefs about the traits of poor people will be primarily negative. Indeed, previous work has found that those who believed in a just world were more likely to report negative perceptions of poor people (Cozzarelli, Wilkinson, & Tagler, 2002; Furnham & Gunter, 1984). The poor are also believed to have fewer positive qualities, such as intelligence, honesty, and competency than those with higher social status (Lott, 2012; Mattan, Kubota, and Cloutier, 2017; Varnum, 2013). Consistent with the just-world hypothesis, people in these studies seem to make the assumption that negative personal characteristics (e.g., lack of conscientiousness and/or impulse control) cause decisions that lead to long-term poverty and inequality. These studies that support the presence of a just world hypothesis suggest that many people hold the belief that psychological attributes (traits, decision-making patterns) cause poverty.

A different theory flips the causal direction. In this class of ideas, the situational aspects of living in poverty produce sub-optimal behaviors and decision-making. Shah, Mullainathan, and Shafir (2012) formalized the theory of the ‘scarcity mindset’ to explain how living in an impoverished environment taxes cognitive abilities and biases decision-making. In a series of studies, these authors found that resource scarcity related to a narrow focus on a current task at the expense of considering future costs or benefits, and that scarcity impeded performance on cognitive tasks. Interestingly, this pattern held regardless of whether scarcity was experimentally induced or observed within subjects experiencing naturalistic variations in resources such as farmers before and after an annual harvest (Mani, Mullainathan, Shafir, & Zhao, 2013). Financial decisions that impede class mobility such as taking out high-interest loans or forgoing bill payments and incurring late fees are common among poor people and, in this model, are thought to stem from the effects of scarcity that are associated with poverty.

A limitation of the current psychological work on inequality is that beliefs about the effects of poverty are rarely if ever directly compared to the actual reality of poverty. For example, research supporting the just world hypothesis reveals that people tend to believe poor people exhibit certain types of financial decision-making or hold particular levels of conscientiousness, and the scarcity mindset theory predicts that these patterns exist due to the nature of poverty itself, but neither of these predictions have been juxtaposed with direct observations of the relation between socioeconomic class, decisions, and personality. Both perspectives assume that the relation between personality traits and patterns of decision-making will be different among the poor than in other groups, but this remains untested. A comparison across socioeconomic class may reveal whether those living in poverty do, in fact, exhibit distinct patterns of responses from those in other classes. Importantly, any documentation of such differences will contain no causal information. Instead, the value of the present research lies in revealing the degree to which individual differences are related to class inequality, not just to form a substantive base for causal theories, but also to more clearly understand the nature of inequality in order to develop effective interventions for reducing it. For example, it is possible that the ‘scarcity mindset’ phenomenon reliably alters financial decision-making, but is not strong enough on its own to cause the stable economic differences across socioeconomic classes.

Aim of the Present Study

The present research speaks directly to assumptions about how those at the lowest level of socioeconomic status tend to make decisions, and whether these patterns are different than those individuals in higher socioeconomic classes. Specifically, the present research tests the assumption that members of the lowest socioeconomic class exhibit traits and behaviors thought to be inconsistent with class mobility. To study this possibility, an online survey was distributed to 1,100 participants across the United States whose annual income ranged from less than $10,000 to more than $200,000. This survey included several different measures of personality and socioeconomic class as well as a financial decision-making task.

Consistent with prior work, this paper uses the term ‘socioeconomic class’ to describe a higher order construct that represents “an individual or group’s relative position in an economic-social-cultural hierarchy” (Diemer et al., 2013). There are two subordinate constructs to this conceptualization of socioeconomic class: socioeconomic status, which refers to the individual or group’s objective prestige and power over resources as afforded by the position in that hierarchy, and subjective social status, which represents the perception of one’s own social class at the individual level. This paper focuses on socioeconomic status as it is a more objective measurement.

Three primary hypotheses were specified a priori to examine the relationships between socioeconomic class and personality and decision-making, in line with the discussed theories’ predictions:

Greater socioeconomic status will relate to making decisions that favor long-term financial gains over short-term ones.

Greater socioeconomic status will relate to increased valuation of long-term financial gains.

Socioeconomic status will be negatively related to trait impulsivity and positively related to conscientiousness and planfulness.

The present research advances research on inequality because it addresses two limitations in the current literature. First, to increase ecological validity, socioeconomic class was not manipulated experimentally in an otherwise homogeneous group but instead measured as it occurs in people’s lives. Second, to guarantee sufficient representation of low-income individuals, participants were sampled equally across income brackets. One limitation of measuring naturally occurring socioeconomic class is that we cannot infer causation. As such, we emphasize that the present research makes no causal claim about socioeconomic class and any observed trends in psychological variables. Instead, our purpose is to reveal whether such trends are observable at all.

Method

Participants and procedure

A national sample of participants was recruited using Qualtrics panels. Participants were eligible to enroll in the study if they were 18 years of age or older, currently lived in the United States, and were native English speakers. The majority of sample participants identified as female (72%), Caucasian and not-Hispanic (82%; 7% as Black and not-Hispanic), and middle class (42%; 24% upper-middle class), and ranged in age from 18–90 (M = 45). This sample was collected based on an a priori power analysis indicating that a sample size of N = 1,073 is required to detect a small (r = 0.1) relationship among personality, temporal discounting, and socioeconomic status with 90% power. The sample was additionally drawn to be roughly equivalent across annual income brackets. Specifically, 160 people were recruited for each annual income bracket of $0−$25,000 and $26,000-$50,00; 153 people were included for the $51,000−$75,000 bracket; and 150 people were included for each income bracket of $76,000−100,000, $101,000−$150,000, $151,000−$200,000, and greater than $201,000 annually. These brackets were selected based on the 2016 poverty threshold ($24,339 for a household of two adults and two children) and median income ($57,617 for all households; U.S. Census Bureau). Notably, participants were not recruited at income rates proportionate to those at the national level; this was intentional, as it allowed us to include more individuals living below the poverty line, who are typically undersampled in psychological research (Henrich, Heine, & Norenzayan, 2010). This sample therefore represents individuals across all socioeconomic classes except the hyper-wealthy and permits us to draw inferences about the decision-making and traits of individuals across class.

Qualtrics distributed the survey to participants based on their eligibility and the targeted income brackets. Participants received the invitation to the Qualtrics survey link, where they were greeted with an online consent form. After again confirming their eligibility to participate and their consent, participants proceeded to the online survey. As a quality assurance step, Qualtrics distributes the survey to 10% of the total requested sample size as part of a “soft launch”. The responses from the soft launch are used to detect any quality control issues with the survey, including fast responding that might reflect lack of engagement with survey items; if soft launch responses are not removed by Qualtrics due to quality control issues, they are included in the final full dataset. If participants in the remainder of the sample respond faster than one third of the median response time from the soft launch sample then their survey session is terminated and their data are not recorded. None of the recorded data had been viewed, cleaned, or altered in any way from its raw form prior to the submission of this registered report.

Materials

A variety of personality trait and socioeconomic class measures were presented to participants, as well as a financial decision-making task. The survey first presented the demographic questions and the financial decision-making task in a fixed order, followed by the personality questionnaires and measures of social class in a randomized order. The entire survey took on average 30 minutes to complete.

Financial decision-making task

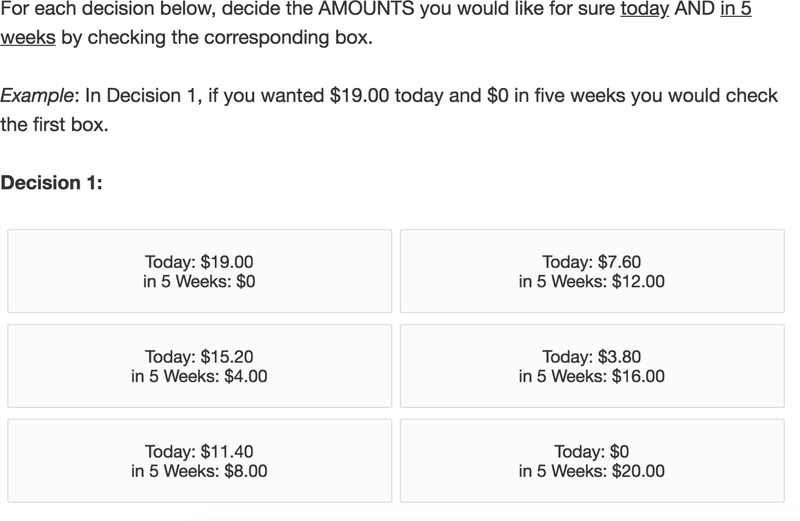

Temporal discounting describes an individual’s preference for receiving smaller rewards in the present over larger ones in the future, reflecting the degree to which a person discounts the value of a future reward. Previous work suggests that temporal discounting is related to impulsivity, and may be related to financial mismanagement (Hamilton & Potenza, 2012). The hypothesis that those living in poverty exhibit more extreme temporal discounting is tested here with the Convex Time Budget Task (CTB; Andreoni, Kuhn, & Sprenger, 2015). In this task, on each item participants choose among six economic reward options varying across two different time frames (one sooner and one later). There are four different pairs of time frames with six reward options each, for a total of 24 decision items total to be made in this task (see Appendix A for an example item). This measure is unique in the number of options it presents the participant with compared to other measures of temporal discounting, which typically present only two options (Frye, Galizio, Friedel, DeHart, & Odum 2016; Richards, Zhang, Mitchell, & de Wit, 1999). For example, in a typical temporal discounting task a participant might be asked to choose between the two options, “$19 today and $0 in 5 weeks” and “$0 today and $20 in 5 weeks,” whereas the CTB adds four intermittent options such as “$11.40 today and $8.50 in 5 weeks” and “$3.80 today and $16.00 in 5 weeks.” Compared to two-option tasks, the CTB provides more robust measurements of time discounting parameters, which is why it was selected for our research (Andreoni, Kuhn, & Sprenger, 2015). Another unique feature of this task is that the trade-off in roughly half of the trials is between an immediate reward (e.g.,“today”) and a delayed reward (e.g., “5 weeks”), as is typical, whereas on the other half the trade-off is between a sooner reward (e.g., “5 weeks”) and a more delayed reward (e.g., “10 weeks”). This allows the effect of the delay period per se to be differentiated from the effect of immediacy, and both effects can be extracted as separate parameters from the model.

Measures of socioeconomic status

To measure socioeconomic status we collected self-reported household income and the number of people living in the respondents’ permanent residence. Participants indicated their household income by selecting one of several brackets: “10,000 or less”; “10,000 −19,999; 20,000 – 29,999”, etc. in brackets of ~$10,000 per level up to $199,999; from $200,000 to $499,999 in brackets of ~$50,000; $500,00-$999,999; and $1,000,000 or more. Number of people living in the household was indicated using a numerical scale from 1–20. To be clear, this survey item was distinct from the income sample parameters used for data collection, which was monitored internally by Qualtrics and not provided to the research team for analysis.

Personality measures

Each measure was included to assess characteristics thought to relate to class mobility and long-term financial goal achievement. Our target personality traits are conscientiousness, a trait that explains variance in a person’s tendency to be organized and hardworking, planfulness, a trait that explains the tendency to think about and plan future goals, and impulsivity, a trait that describes a person’s tendency to act immediately on emergent urges. Specifically, the just world theory suggests that people believe conscientiousness and planfulness to be related to class inequality, while the theory of scarcity mindset suggests that lack of access to resources causes short-term-focus, an aspect of impulsiveness, that reinforces class status. The measures included in the survey therefore are: the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS, 30 items; Patton, Stanford & Barratt, 1995), the Conscientiousness scale from the 44-item Big Five Inventory (BFI-C, 9 items; John & Srivastava, 1999), and the Planfulness Scale (30 items; Ludwig, Srivastava, & Berkman, 2017). While planfulness and impulsivity are theorized to be facets of conscientiousness, including measures of these traits allows us to tap into specific variance potentially related to income mobility that is distinct from the broader conscientiousness factor (see scale citations for more details). Responses to the BFI-C and Planfulness Scale used a five-point Likert scale (1=Strongly disagree; 3=Neither disagree nor agree; 5 = Strongly agree), while responses to the BIS were coded using a four-point scale (1=Rarely/never, 2=Occasionally, 3=Often, 4=Almost Always/Always).

Statistical analysis

Our hypotheses focus on SES, which is operationalized as Income-to-Needs Ratio (INR) and derived from the measures described above. To calculate INR, we first calculated “adjusted household income” based on the self-reported household income item. The adjustment is to place participants in the middle of the bracket that they selected (so, $15,000 if they responded “10,000−19,999”; $750,000 if they responded “$500,00−$999,999”, etc.). This compensates for having brackets instead of exact figures by pulling all responses together in the center values. Then INR is calculated by dividing adjusted household income by the U.S. Census poverty threshold for a household of the participants’ size and age. We used the 2016 U.S. Census poverty thresholds for reference because they are the most recently published thresholds at the time of this writing. We used this variable because it allows us to more precisely characterize participants’ socioeconomic status by adjusting for household size and composition. Additionally, this variable is easily interpretable – those with an INR greater than 1 are living above the poverty line, and those with an INR of 1 or lower are living below it.

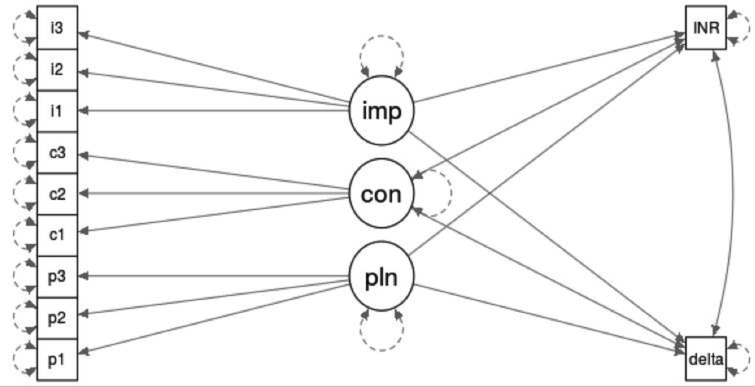

Our primary criterion variables are the scales for each of the personality measures and two parameters from the time discounting task. Measurement models for the personality traits are specified based on their original published descriptions. We first tested to confirm that loadings are invariant across income categories, and subsequently perform all analyses using the latent personality variables. This method best accounts for measurement error and differences in how people use the scales. The temporal discounting task yields two parameters relevant to our research question: δ (delta) represents a participant’s overall temporal discounting rate (i.e., their tolerance for waiting for rewards), and β (beta) represents a participant’s present bias (i.e., the additional amount they discount future rewards if the sooner reward is received today as compared to the set of trials where even the sooner reward is in the future). We extract these parameters using the regression model proposed in Andreoni, Kuhn, and Sprenger, (2015). Specifically, beta and delta are estimated using the following non-linear regression equation:

where xt is the amount chosen by the participant to receive as soon as possible (that is, at some time, t, before the delayed amount), 20 is the maximum payout amount possible at time t + k, beta is the amount of bias toward the present (that is, a multiplier on the discounting rate when time t = today, in which case t0 = 1, and otherwise 0), delta is the discounting rate, k is amount of time between the sooner and later options, P is the interest rate (such that P·xt + xt+k = 20, which describes that when interest rates are higher, sooner rewards, xt, are lower than delayed rewards, xt+k), and α (alpha) governs the curvature of the utility function (such that lower values result in a more gradually varying sensitivity to differences in delay or interest rate).

We used a regularization procedure, which leverages information from the whole sample to increase the robustness of the person-level temporal discounting parameters. This began with estimating the CTB model coefficients using a non-linear mixed effects (NLME) model using the nlme package (Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, Sarkar D and R Core Team, 2018) in R (version 3.4.4; R Core Team, 2018), allowing the coefficients for alpha, beta, and delta to vary by participant. We then extracted the individual participant coefficient estimates from this model to use in subsequent analyses. The advantage of this approach, rather then estimating a model separately for each participant, is that by pooling information across participants one is able to overcome convergence problems and obtain estimated coefficients for participants with noisy data. This also serves to “shrink” the estimates for participants with noisy data toward the mean of the sample and in doing some provides some regularization. Optimization of the NLME model may be aided by providing the nlme function a list of non-linear regression models fit to each participant’s individual data using nls (in the base-R stats package). The model fit using these random effect starting values is compared to a model fit starting with default values (to ensure that this step does improve model quality). We are then able to extract the individual coefficient estimates for all model parameters.

This step also provided an opportunity to determine whether any participants’ models did not converge without the partial pooling of information in the NLME model. Before estimating any relationships between variables, we examined the data for behavior that would indicate a clear departure from model-expectations. Possible reasons for non-convergence, a priori, might include always choosing the sooner (or later) option, choosing inconsistently (e.g., choosing both $19 and $17 today, but waiting 5 weeks for a total of $18.40), or choosing randomly; indeed, strong departures from model expectations may be interesting in themselves. We therefore had included a plan to examine the relationship between membership in “converging” and “non-converging” groups with socioeconomic and personality variables in our registration of this paper, but as we found no participants belonging to the latter category this analysis was not carried out.

To test our three hypotheses of interest we have run three separate reflective structural equation models. The first two models break out aspects of time discounting into the two parameters of future bias and patience, and the third model offers a more holistic test of the construct of time discounting.

1.) The hypothesis regardingthe relationship of SES to the relative value of immediate gains was tested with the significance test on the covariance between beta and INR. Delta, planfulness, conscientiousness, and impulsivity scores were included in the model as covariates. We expected smaller beta values to be associated with lower INR1

2.) The hypothesis about the relation of SES to the value of long-term gains was tested with the significance test on the covariance between delta and INR. Planfulness, conscientiousness, and impulsivity scores were again included in the model as covariates. We expected smaller delta values to be associated with lower INR2

3.) The hypothesis about the relation of SES to personality traits was tested by regressing INR on planfulness, conscientiousness, and impulsivity in a single regression model. We expected higher planfulness, and conscientiousness, and lower impulsivity, to be associated with higher INR.

Given the directional nature of our hypotheses, tests of the variable coefficients were one-tailed and evaluated at the .05 level. Results are interpreted according to the sign and significance of the regression coefficients. A significant coefficient p value will be taken to indicate the improvement of model fit to the data, and the value of that coefficient to describe how it is related to other variables in the model. Given the high power of this sample to detect small effects, variables with coefficients that do not reach statistical significance are interpreted as being unassociated with socioeconomic status.

We include all personality measures as covariates (i.e., simultaneous predictors) of socioeconomic status because we are interested primarily in the unique contributions of these constructs, and the unique association between SES and discounting behavior over-and-above these constructs (Lynam, Hoyle, & Newman, 2006). In other words, we wish to draw conclusions about the association between SES and discounting behavior for individuals who otherwise are similar in their level of planfulness, impulsivity, and overall contentiousness. To examine the sensitivity of our conclusions to these partial correlations, we report the zero-order correlations among all collected variables (both latent, and computed-scale-scores), though no conclusions are drawn from these correlations alone. We also report cases in which hypothesis tests were sensitive to non-registered variations in the analysis plan, including log-transforming INR, and allowing the covariates to covary freely (complete analysis output is available at the project Open Science Framework page, https://osf.io/bjrw2/).

If participants missed greater than or equal to 50% of items on a personality scale, they were coded as missing a score for that scale and not included in analyses involving that scale. Due to the nature of the CTB task, participants who missed more than one item per timeframe pair are coded as missing and excluded from analysis. Finally, participants who did not self-report household income are excluded from analysis.

Results

Descriptives and correlations

Table 1 contains a summary of the descriptive statistics for all of our collected measures. Of particular note is income-to-needs ratio, which ranged from 0.15 to 60.07 in our sample (M = 6.18, SD = 5.97, median = 4.53), and the distribution of which was right-skewed. Seventy-nine participants in our sample reported annual incomes that place them at or below the poverty threshold for their household composition and size (INR <= 1; n = 131 <= 1.5). Separately, we also note that we have reversed the signs of all reported beta and delta parameter coefficients to aid with interpretability; as these variables increase toward 1, they indicate less discounting of future rewards and present bias, hence our decision to reverse the signs to align with the natural interpretation that larger values indicate more of something. For the reversed variables, a value of −1 indicates insensitivity to the delay period (for delta) or to the immediacy of the sooner reward (beta). Reverse-coded variables increase from −1 toward 0 as individuals discount more with increased delay, or as they discount especially so for immediate, sooner rewards. Values less than −1 are also possible3

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of measured variables

| n | Mean | Standard deviation | Observed range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Planfulness | 1,095 | 3.61 | 0.49 | 1.7 – 4.93 |

| INR >= 1 | 954 | 3.63 | .49 | 1.7 – 4.93 |

| INR< 1 | 79 | 3.49 | 0.43 | 2.50 – 4.63 |

| BIS | 1,096 | 1.98 | 0.38 | 1.10 – 3.57 |

| INR >= 1 | 957 | 1.97 | 0.38 | 1.10 – 3.57 |

| INR< 1 | 79 | 2.03 | 0.33 | 1.23 – 2.87 |

| BFI-C | 1,095 | 3.54 | 0.31 | 2.25 – 4.66 |

| INR >= 1 | 955 | 3.53 | 0.30 | 2.25 – 4.66 |

| INR< 1 | 78 | 3.51 | 0.33 | 2.77 – 4.39 |

| beta | 1,079 | −0.92 | −0.12 | −0.57 – −1.23 |

| INR >= 1 | 942 | −0.92 | −0.12 | −0.57 – −1.23 |

| INR< 1 | 76 | −0.91 | −0.13 | −0.59 – −1.14 |

| delta | 1,079 | −0.98 | −0.02 | −0.94 – −1.01 |

| INR >= 1 | 942 | −0.98 | −0.02 | −0.94 – −1.01 |

| INR< 1 | 76 | −0.98 | −0.02 | −0.94 – −1.01 |

| INR | 1,038 | 6.18 | 5.97 | 0.15 – 60.07 |

Note: BIS= Barratt Impulsiveness Scale, BFI-C = conscientiousness factor of the BFI, INR =income-to-needs ratio.

Table 2 presents the bivariate correlations among our variables of interest. We present these results for descriptive purposes and rely on our formal model tests to infer conclusions about the relationships among these variables exhibited in the data.

Table 2.

Correlation matrix of measured variables.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Planfulness | BIS | BFI-C | INR | beta | delta | ||

| 1 | Planfulness | −.78 | .74 | .22 | .08 | .05 | |

| 2 | BIS | −.72 | −.82 | −.20 | −.06 | −.02 | |

| 3 | BFI-C | .38 | −.30 | .14 | .04 | .01 | |

| 4 | INR | .22 | −.19 | .05 | .09 | .06 | |

| 5 | beta | .07 | −.05 | .02 | .09 | .77 | |

| 6 | delta | .04 | −.01 | .00 | .06 | .77 |

Note: Boldedvalues are significant at p< .05 (corrected for 15 comparisons using the Holm correction). BIS = Barratt Impulsiveness Scale, INR = income-to-needs ratio, BFI-C = conscientiousness factor of the BFI. Smaller delta values indicate decreased temporal discounting; smaller beta values indicate less preference for rewards available immediately. Values in the upper triangle are correlations estimated using latent personality variables.

Measurement invariance

We tested for invariance of factor loadings (metric invariance) for each personality scale latent variable across income brackets; substantive inferences with respect to factor covariances can be made if the test of metric invariance is satisfied (Gregorich, 2006). To check for invariance, we compared the fit of structural models of personality traits with indicator loadings constrained to equality across income groups to the fit of parallel models with indicator loadings allowed to vary by income group. The primary criterion for rejecting invariance was a difference in the McDonald fit index (ΔMFI) of < −.012, indicating much poorer fit of the constrained model. We also report differences in root mean square error of approximation (ΔRMSEA), and the comparative fit index (ΔCFI). Our results indicated that metric invariance did not hold for the conscientiousness measure, ΔMFI = −0.019, ΔCFI = −0.016, ΔRMSEA = −0.009. Further inspection of the modification indices suggested that this was due to items 3 (“[d]oes a thorough job,”) and 13 (“[i]s a reliable worker”). Removal of these two items resulted in acceptable fit decrement when constraining loadings to be equal across income brackets (ΔMFI = −0.005, ΔCFI = −0.006, ΔRMSEA = −0.016). Thus, we included an additional test for all of our models using the modified-to-be-invariant conscientiousness scale in order to examine the sensitivity of our results to measurement quality. We found that across all of our hypothesis tests, the modified model results were consistent with the original models and therefore only report the latter below.

Hypotheses testing

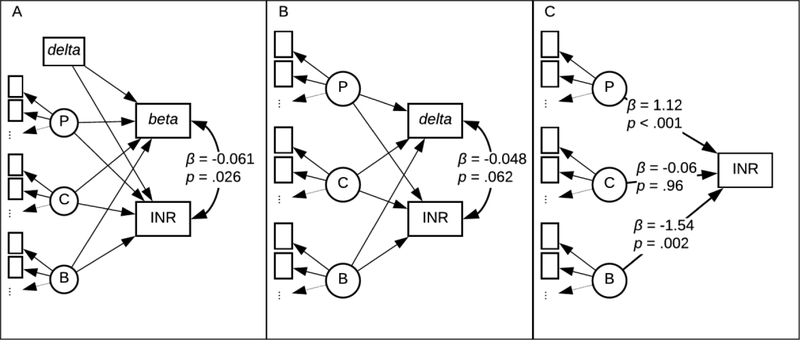

To test our first hypothesis (regarding socioeconomic status and immediate gains), we built a model testing the covariance between beta and INR, with delta and the personality traits included as covariates (see Figure 2A). Results showed that there was a statistically significant negative covariance between INR and a willingness to give up even more of a future reward if the sooner reward is obtained today (controlling for a person’s overall discounting, delta, and the personality variables), b = −.03, β = −.06, p = .026. People with a lower INR showed more of a present bias. On an exploratory basis, we further examined the relationship among beta, delta, and INR with the measured personality traits, though we highlight that these coefficients were not the target of any of our a priori hypotheses. Delta was found to significantly positively correlate with beta (as would be expected if people who value sooner rewards also tend to value them especially so if they are obtained today), b = 4.20, β = .77, p < .001; see Table 3. INR was found to be significantly and positively related to planfulness, b = 7.14, β = .18, p < .001, which corresponds in standardized terms to roughly a point increase in INR for each standard deviation increase in planfulness score. INR also significantly and negatively related to impulsivity, b = −1.57, β = −.10, p = .002, corresponding to roughly two-thirds of a point increase in INR for each standard deviation decrease in BIS score; see Table 3. Post-registration sensitivity analysis further revealed that the covariance between INR and beta was sensitive to log transformations of INR, b = .001, β = .018, p = .029.

Figure 2.

Labeled paths correspond to registered hypothesis tests. Coefficient βs are standardized; p-values are one-sided. Latent variables are denoted by circles; observed variables are denoted by rectangles. Dotted lines and arrows indicate that latent factors load on more than just the two illustrated observed variables. P = planfulness; C = conscientiousness factor of the BFI; B = Barratt Impulsiveness Scale. Residual variances not shown.

Table 3.

Exploratory linear regressions on beta parameter and INR

| b | SE | β | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| beta parameter | ||||

| delta parameter | 4.20 | 0.11 | 0.77 | < 0.001 |

| Planfulness | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.22 |

| BFI-C | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.64 |

| BIS | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.15 |

| INR | ||||

| delta parameter | −13.17 | 8.3 | −0.05 | 0.11 |

| Planfulness | 7.14 | 1.94 | 0.18 | < 0.001 |

| BFI-C | −0.7 | 0.42 | −0.06 | 0.01 |

| BIS | −1.57 | 0.52 | −0.10 | 0.002 |

Note: BIS = Barratt Impulsiveness Scale, INR = income-to-needs ratio, BFI-C = conscientiousness factor of the BFI. Two-tailedp-valuesreported.

Next, to test the second hypothesis about the relationship between valuation of long-term gains and socioeconomic status, we built a model testing the covariance between delta and INR, again including personality traits as covariates (Figure 2B). INR did not significantly correlate with decreased preference for waiting for larger reward values, b = −.006, β = −.048, p = .062. Our exploratory tests of relationships with personality traits revealed that delta was negatively associated with planfulness, b = −0.011, β = −.078, p = .032, controlling for levels of conscientiousness and impulsivity, indicating that an individual with a higher score on the Planfulness scale is very slightly more likely to discount less than a person with the same score on the BFI-C and BIS scales but a lower Planfulness score (see Table 4). We again observed that INR was significantly positively correlated with scores on the Planfulness scale, b = 7.27, β = .18, p < .001, and significantly negatively correlated with scores on the BIS, b = −1.58, β = −.10, p = .003.

Table 4.

Exploratory linear regressions on delta parameter and INR

| b | SE | β | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| delta parameter | ||||

| Planfulness | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.08 | 0.03 |

| BFI-C | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.04 | 0.28 |

| BIS | −0.001 | 0.002 | −0.01 | 0.72 |

| INR | ||||

| Planfulness | 7.27 | 1.95 | 0.18 | < 0.001 |

| BFI-C | −0.72 | 0.42 | −0.06 | 0.088 |

| BIS | −1.56 | 0.52 | −0.10 | 0.003 |

Note: BIS = Barratt Impulsiveness Scale, INR = income-to-needs ratio, BFI-C =conscientiousness factor of the BFI. Two-tailedp-valuesreported.

A final model testing the unique associations between personality constructs and SES contained only the latent personality trait variables and the observed INR variable (see Figure 2C). The patterns observed in the prior results were again apparent, with planfulness (b = 7.45, β = 1.12, p < .001) and impulsivity (b = −1.54, β = −.10, p = .002) found to significantly relate to INR in the hypothesized direction: greater planfulness and lower impulsivity related to higher SES. Conscientiousness was not related to INR (b = −0.72, β = −.06, p = .96).

Discussion

The goal of this work was to test whether and how socioeconomic status relates to temporal discounting and relevant personality traits in a large, ecologically valid sample. We constructed a priori structural equation models to test a set of hypotheses about the relationships among these variables that were derived from both lay and scientific theories of the psychology of poverty. We found mixed support for these hypotheses.

First, we tested the hypothesis that SES is negatively associated with a preference for sooner (over later) rewards if the sooner reward is obtained today rather than in the future, operationalized with the beta parameter from the CTB task. When controlling for a person’s baseline discounting rate (the delta parameter), our results did support this hypothesis, though the standardized effect size is small (β = .06) and was greatly diminished when INR was log transformed. We next tested the hypothesis that SES would be positively associated with reduced preference for sooner rewards, indexed with the delta parameter. We observed no statistically significant relationship between these variables, though we were well powered to detect such an association. Finally, we tested the hypothesis that SES would track positively with trait conscientiousness and planfulness, and negatively with impulsivity. This hypothesis was partially supported, with a positive relationship between SES and planfulness and a negative relationship between SES and impulsivity observed in all three structural equation models. No statistically significant relationship with conscientiousness was found based on our registered one-tailed hypothesis as the observed association was negative. Though the values of the coefficients might seem small – an increase of one standard deviation in planfulness corresponding to an expected one point increase in INR, and one standard deviation in impulsivity to .60 of a point in INR – it’s important to note that the parity of income-to-needs is 1; thus, one standard deviation in either of these traits could be associated with the difference between living below or above the poverty line.

One interpretation of these results is consistent with scarcity theory. Poorer people were not observed to have increased preference for sooner rewards (though they were observed to be slightly more present-biased) than people higher in SES, but there was a positive link between planfulness and SES. This latter association could reflect the constraints of poverty on poor individuals. Scoring high in planfulness reflects participants’ reporting that they set explicit plans to reach their goals and take time to reflect on how their present actions relate to their long-term plans. Engaging in these psychological processes may be privileges that are forgone when living in an environment of scarcity, even if a person is not otherwise inclined to discount future outcomes. If, as the theory proposes, scarcity restricts attention to present threats and drains cognitive resources, the observation that those living in impoverished environments score lower in planfulness while showing equivalent preference for sooner rewards is consistent- it seems logical that having one’s mind occupied by threats to one’s survival reduces the time and energy available for setting reliable, effective plans. In the laboratory, however, where there is no apparent scarcity constraint, poorer people did not tend to show a preference for sooner rewards in general. The slight increase in preference for sooner rewards if the sooner reward is obtained today complicates the picture somewhat, though it is plausible that scarcity may have a psychological effect not on different degrees of delay, but more specifically on preferences for rewards that can be used immediately to solve problems versus rewards that accrue in the future.

This latter point relates to another possible interpretation of the results–that the temporal discounting task used taps into people’s aspirational choices, rather than assessing the way people actually make decisions in real life. That is, being faced with theoretical rewards ranging across temporal and monetary values on a computer screen is undoubtedly different from considering taking out a high-interest loan to pay this month’s rent. This may be why we did not observe a relationship between SES and patience for future values on the CTB task but did observe one between SES and scores on the BIS – ecological impulsivity is qualitatively different from impulsivity measured on laboratory tasks. Relying on a survey measure of financial decision-making is an admitted limitation of this study, but the decision to use such measure was made in order to increase our sample size. Nevertheless, this limitation also presents a ripe opportunity for future research to determine whether more direct measures of financial decision-making and/or temporal discounting exhibit different patterns across SES.

We have discussed the consistencies of our results with scarcity theory, but what of the implications for the lay “just world” theory? One might be inclined to conclude that these results are also consistent with it – less planful, more impulsive people seem to be poorer. However, a less superficial engagement with the just world notion of deservingness makes prominent two of its primary assertions: first, that the observed personality traits cause, to some extent, income; and second, that such an outcome is justified, or desirable. This first claim is just one of many causal stories these data are consistent with, and scarcity effects are one example of an alternative. With regards to the second assertion, no empirical finding can possibly adjudicate whether, if such a causal story is true, it is a just and desirable state of affairs.

In the face of this final point we underscore the reminder that our results indicating relationships between SES and the personality traits of planfulness and impulsivity are non-directional and not causal. We did not set out to test lay or scientific theories about psychology and poverty, but instead wanted to determine whether relationships between the two existed at all. Given the careful design of our research to meet this aim, we conclude that relationships between SES and specific personality traits, as well as a component of temporal discounting, do indeed exist based on the present data. It is our hope that our results will be used to inform the development and refinement of theories about the effects of poverty, and to serve as an informative source for those wishing to inform public policy with empirical research.

Figure 1.

Example model of relationships to be tested among variables of interest. In this model, the correlation between income-to-needs ratio (INR) and an extracted temporal discounting parameter (delta) is observed, accounting for personality factors of impulsivity (imp), conscientiousness (con), and planfulness (pln).

Table 5.

Model 3 results

| b | SE | β | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| INR | ||||

| Planfulness | 7.44 | 1.98 | 0.19 | < 0.001 |

| BFI-C | −0.72 | 0.42 | −0.06 | .96 |

| BIS | −1.54 | 0.52 | −0.10 | 0.002 |

Note: BIS = Baratt Impulsiveness Scale, BFI-C = conscientiousness. One-tailed p-values reported.

Appendix A: Sample Convex Time Budget Task

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Open Practices

This paper was submitted as a registered report, wherein all hypotheses and data analysis plans were established prior to observing the collected data and producing results. Materials, R code for analyses, and the study data are open and available at the project Open Science Framework page, https://osf.io/bjrw2/.

Smaller beta values indicated more present-bias. The results below use a reverse-coded version of this parameter to clarify interpretation.

Smaller delta values indicated more temporal discounting. The results below use a reverse-coded version of this parameter to clarify interpretation.

Note that the hypothesis described in the introduction are in terms of the raw parameters, not the reverse-coded parameters. Thus we expected bigger values of the reverse coded parameters to be associated with lower INR.

References

- Andreoni J, Kuhn MA, & Sprenger C (2015). Measuring time preferences: A comparison of experimental methods. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 116, 451–464. [Google Scholar]

- Carr M, & Wiemers EE (2016). The decline in lifetime earnings mobility in the US: Evidence from survey-linked administrative data. Washington Center for Equitable Growth. [Google Scholar]

- Chetty R, Grusky D, Hell M, Hendren N, Manduca R, & Narang J (2017). The fading American dream: Trends in absolute income mobility since 1940. Science, 356(6336), 398–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cozzarelli C, Tagler MJ, & Wilkinson AV (2002). Do middle-class students perceive poor women and poor men differently?. Sex Roles, 47(11–12), 519–529. [Google Scholar]

- Diemer MA, Mistry RS, Wadsworth ME, López I, & Reimers F (2013). Best practices in conceptualizing and measuring social class in psychological research. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 13(1), 77–113. [Google Scholar]

- Frye CC, Galizio A, Friedel JE, DeHart BW, & Odum AL (2016). Measuring delay discounting in humans using an adjusting amount task. Journal of visualized experiments: JoVE, (107). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furnham A, & Gunter B (1984). Just world beliefs and attitudes towards the poor. British journal of social psychology, 23(3), 265–269. [Google Scholar]

- Gregorich SE (2006). Do Self-Report Instruments Allow Meaningful Comparisons Across Diverse Population Groups? Testing Measurement Invariance Using the Confirmatory Factor Analysis Framework. Medical Care, 44, S78–S94. 10.1097/01.mlr.0000245454.12228.8f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton KR, & Potenza MN (2012). Relations among delay discounting, addictions, and money mismanagement: Implications and future directions. The American journal of drug and alcohol abuse, 38(1), 30–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrich J, Heine SJ, & Norenzayan A (2010). Beyond WEIRD: Towards a broad-based behavioral science. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33(2–3), 111–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John OP, & Srivastava S (1999). The Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. Handbook of personality: Theory and research, 2(1999), 102–138. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner MJ (1980). The belief in a just world In The Belief in a just World (pp. 9–30). Springer, Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig RL, Srivastava S, & Berkman ET (2017). The Planfulness Scale. DOI 10.17605/OSF.IO/56JA2 [DOI]

- Lott B (2012). The social psychology of class and classism. American Psychologist, 67(8), 650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynam DR, Hoyle RH, & Newman JP (2006). The Perils of Partialling: Cautionary Tales From Aggression and Psychopathy. Assessment, 13(3), 328–341. 10.1177/1073191106290562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mani A, Mullainathan S, Shafir E, & Zhao J (2013). Poverty impedes cognitive function. Science, 341(6149), 976–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OECD (2018), Income inequality (indicator). doi: 10.1787/459aa7f1-en (Accessed on 02 May 2018) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patton JH, Stanford MS, & Barratt ES (1995). Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. Journal of clinical psychology, 51(6), 768–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team (2018). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria: URL: https://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Richards JB, Zhang L, Mitchell SH, & Wit H (1999). Delay or probability discounting in a model of impulsive behavior: effect of alcohol. Journal of the experimental analysis of behavior, 71(2), 121–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah AK, Mullainathan S, & Shafir E (2012). Some consequences of having too little Science, 338(6107), 682–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau (2017). The Supplemental Poverty Measure. [Google Scholar]

- Varnum ME (2013). What are lay theories of social class?. PloS one, 8(7), e70589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]