Abstract

Purpose

In animal models, insulin resistance without severe hyperglycemia is associated with retinopathy, however, corroborating data in humans is lacking. This study aims to investigate the prevalence of retinopathy in a population without diabetes and evaluate the association of insulin resistance and retinopathy within this group.

Methods

The study population included 1914 adults age ≥40 without diabetes who were assigned to the morning, fasted group in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005-2008, conducted by the Centers for Disease Control. Retinopathy was determined using fundus photos independently graded by a reading center and insulin resistance was determined using the homeostatic model of insulin resistance.

Results

Prevalence of retinopathy in those without diabetes was survey design adjusted 9.4% (174/1914). In multivariable analyses, retinopathy was associated with insulin resistance (HOMA-IR OR: 1.09, 95% CI: 1.03, 1.16; p=0.0030), male gender (OR: 1.39, 95% CI: 1.04, 1.85; p=0.0267), and age (OR: 1.03, 95% CI: 1.01, 1.05; p=0.0203).

Conclusions

Insulin resistance in the absence of overt hyperglycemia could be an early driver of retinopathy.

Keywords: diabetic retinopathy, insulin resistance, NHANES, insulin

Introduction

Diabetes causes progressive retinal damage through poorly understood mechanisms. Although excess plasma glucose is thought to drive diabetic retinopathy (DR), hyperglycemia accounts for only 11% of variability in its risk1 suggesting the involvement of other factors. Moreover, lowering glucose with insulin, insulin secretogogues, or insulin sensitizers confounds attempts to dissociate effects of glucose itself versus insulin signaling in diabetic complications.

Insulin resistance occurs in both type 1 and type 2 diabetes. In rodent models, insulin resistance without severe hyperglycemia is associated with retinopathy2. In humans, similar data linking insulin resistance in the absence of overt hyperglycemia to retinopathy is lacking. Here we show that retinal lesions – typical of DR – are associated with insulin resistance but not hyperglycemia in patients without diabetes.

Methods

Data were gathered from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2005-20083. NHANES is a cross-sectional survey of health and nutrition of the United States civilian, noninstitutionalized population conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The study used a stratified, multi-stage probability sampling approach to accurately represent the United States population. Sample weights were assigned to each sample person; sample weights represent the number of people represented by each sample person. Sample weights were calculated to be representative of the United States civilian noninstitutionalized population and adjusted according survey non-response, over-sampling, post-stratification, and sampling error. For example, a 33 year-old Caucasian sample person, #31183, represents 126,819 actual persons whereas a 78 year-old African American sample person, #31263, represents 20,128 actual persons. Data were collected through home interviews, questionnaires, medical examinations and laboratory testing in a mobile examination center. Participants were randomly assigned to either a morning fasting group or an afternoon non-fasting group. Fasting labs, such as fasting glucose, insulin, and fasting lipid panel were only collected for the morning group. The analyses in this report include participants in NHANES aged 40 years and older because 2-field non-mydriatic retinal photography was performed on this age group only. Retinal photographs were graded using Early Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) criteria. Retinopathy was determined by the existence of ≥1 retinal microaneurysms or retinal blot hemorrhage with or without more severe lesions (hard exudates, soft exudates, intraretinal microvascular abnormalities, venous beading, retinal new vessels, preretinal and vitreous hemorrhage, or fibrous proliferation) using ETDRS standards4. Participants with available retinal photographs and who were in the morning/fasted group were included in this study. Participants were excluded if they self-reported a diabetes diagnosis or being treated for diabetes, if they had glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) of ≥6.5%, or if fasting plasma glucose (FPG), fasting insulin levels or ETDRS grades for both eyes were unavailable. Age, gender, race, HbA1c, mean arterial blood pressure (MABP), serologic data, and ETDRS score for each participant were recorded. MABP data were excluded for participants who indicated they had drank alcohol, coffee, or smoked a cigarette in the last 30 minutes. A homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) was calculated as (FPG × fasting insulin) ÷ 4055.

Statistical analysis

SAS version 9.4 (Cary, NC) was used to evaluate continuous variables with Student’s t tests and categorical variables with Rao-Scott χ2. SAS procedures PROC SURVEYFREQ, PROC SURVEYREG, PROC SURVEYMEANS, and PROC SURVEYLOGISTIC were used for analysis. Relevant covariates for retinopathy were evaluated by multivariable logistic regression. Variables were selected based on statistically significant differences between the retinopathy and no retinopathy in univariable analysis. Ethnicity was added to the model due to its clinical significance. NHANES sampling weights were incorporated into analyses. A two-tailed p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

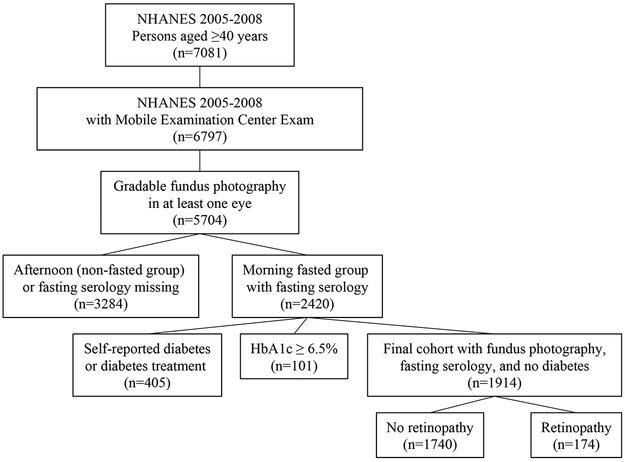

Among 5704 participants with gradable retinal photography in at least one eye, 2420 had fasting serology data available. After excluding 405 patients for self-reported diabetes treatment and 101 for HbA1c of ≥6.5%, 1914 patients were included in the final analysis (Figure 1). Retinopathy was present in 9.4% of patients. In the majority of these cases, retinopathy was mild (Table 1). In univariable analyses, compared to patients without retinal lesions, those with retinopathy were older (58.8 years versus 55.2 years, respectively) and more likely to be male, had higher HbA1c (5.5% versus 5.4% respectively, Table 1), had higher BUN (blood urea nitrogen) and creatinine. In this non-diabetic cohort, 1286 participants had a HbA1c of ≤5.6%, while 628 participants had a HbA1c of HbA1c of 5.7%−6.4%. Of the 174 participants with retinopathy, 96 had a HbA1c of ≤5.6% while 78 had a HbA1c between 5.7% and 6.4%. MABP, body mass index, triglycerides, LDL (low density lipoprotein), HDL (high density lipoprotein), urinary albumin to creatinine ratio, and C-reactive protein were comparable between groups. HOMA-IR was higher in patients with retinopathy than those without (Table 1). In this cohort, 102 participants had microaneurysms only, however, the number of microaneurysms is not available in NHANES.

Figure 1.

Cohort selection flowchart for National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) 2005–2008 fasting cohort with gradable fundus photography in at least one eye and without diabetes.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys 2005-2008 Participants Aged 40 Years and Older in the Fasting Cohort Without Diabetes, and by Retinopathy Status

| Total Cohort | Retinopathy | No Retinopathy | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | 1914 (100) | 174 (9.4)* | 1740 (90.6)* | |

| Mean age, years (SEM) | 55.5 (0.44) | 58.8 (1.50) | 55.2 (0.43) | 0.0187 |

| Gender (%) | 0.0082 | |||

| Male | 952 (47) | 94 (9.2) | 858 (90.8) | |

| Female | 962 (53) | 80 (6.5) | 882 (93.5) | |

| Ethnicity (%) | 0.1505 | |||

| Caucasian | 1129 (80) | 95 (7.3) | 1034 (92.7) | |

| African American | 295 (7.8) | 39 (11.3) | 256 (88.7) | |

| Mexican American | 289 (5) | 20 (6.1) | 269 (93.9) | |

| Other | 201(6.9) | 20 (10.8) | 181 (89.2) | |

| HbA1c, % (SEM) | 5.4 (0.01) | 5.5 (0.04) | 5.4 (0.01) | 0.0018 |

| HOMA-IR (SEM) | 2.8 (0.09) | 3.8 (0.43) | 2.8 (0.08) | 0.0182 |

| Fasting Glucose, mg/dL (SEM) | 101.9 (0.41) | 103.9 (1.16) | 101.7 (0.42) | 0.0786 |

| Fasting Insulin, μU/mL (SEM) | 10.9 (0.31) | 14.1 (1.31) | 10.7 (0.28) | 0.0106 |

| MABP, mm Hg (SEM) | 88.8 (0.30) | 89.8 (1.11) | 88.7 (0.29) | 0.3203 |

| BMI, kg/m2 (SEM) | 28.5 (0.14) | 29.5 (0.63) | 28.4 (0.15) | 0.1007 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL (SEM) | 140.0 (2.68) | 140.6 (7.38) | 140.0 (2.93) | 0.9374 |

| LDL, mg/dL (SEM) | 122.0 (0.86) | 118.8 (4.09) | 122.3 (0.93) | 0.4293 |

| HDL, mg/dL (SEM) | 56.4 (0.40) | 54.3 (1.70) | 56.7 (0.42) | 0.1810 |

| CRP, mg/dL (SEM) | 0.41 (0.03) | 0.43 (0.05) | 0.40 (0.03) | 0.6972 |

| BUN, mg/dL (SEM) | 13.1 (0.16) | 14.3 (0.43) | 13.0 (0.16) | 0.0049 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL (SEM) | 0.91 (0.01) | 0.98 (0.03) | 0.90 (0.01) | 0.0173 |

| Urinary Albumin/ Creatinine Ratio, mg/g (SEM) | 24.3 (3.91) | 37.4 (8.89) | 23.2 (4.16) | 0.1545 |

| ETDRS Score, n (%) | ||||

| No DR (10-13) | 0 | 1740 (100%) | ||

| Mild (14-31) | 169 (97.1%) | 0 | ||

| Moderate/Severe (41-51) | 5 (2.9%) | 0 | ||

| Proliferative (60-80) | 0 | 0 |

HOMA-IR = homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance, MABP = mean arterial blood pressure, BMI = body mass index, LDL = low density lipoprotein, HDL = high density lipoprotein, CRP = C-reactive peptide, BUN = Blood Urea Nitrogen, ETDRS = early detection diabetic retinopathy study

These percentages are adjusted according to NHANES survey weights.

Comparing fasting and non-fasting groups, there was no difference in age (non-fasting: 55.6 years (SEM: 0.47) vs fasting: 55.5 years (SEM: 0.45) p=7980), gender (p=0.5885), ethnicity (p=0.7980), HbA1c (non-fasting: 5.4% (SEM: 0.01) vs fasting: 5.4% (SEM: 0.01) p=0.6056), CRP (non-fasting: 0.41 mg/dL (SEM:0.02) vs fasting: 0.41 mg/dL (SEM: 0.03) p=0.9924), or BMI (non-fasting: 28.6 (SEM: 0.21), fasting: 28.5 (SEM: 0.14) p=0.5617). However, the non-fasting group had higher MABP (non-fasting: 91.0 mmHg (SEM: 0.33) vs fasting: 88.8 mmHg (SEM: 0.30) p<0.0001). Participants with missing fasting serology or HbA1c had the same rates of retinopathy.

In multivariable analysis, HOMA-IR (OR: 1.09, 95% CI: 1.03-1.16, p=0.003), male gender (OR: 1.39, 95% CI: 1.04, 1.85, p=0.0267), and older age (per year, OR: 1.03, 95% CI: 1.01, 1.05; p=0.0203), were independent predictors of retinopathy after adjusting for HbA1c (OR: 1.50, 95% CI: 0.82, 2.74; p=0.1778) and Ethnicity (African American OR: 1.74, 95% CI: 0.97, 3.11; p=0.5376, Mexican American OR: 0.93, 95% CI: 0.52, 1.64; p=0.7881, Other Ethnicity OR: 1.49, 95%CI: 0.67, 3.32, p=0.3233) (Table 2). HOMA-IR >5 was associated with 64% increased odds of retinopathy (OR:1.64, 95% CI: 1.03, 2.62, p=0.0393) compared to those with an index <3.

Table 2.

Multivariable Logistic Regression Model for Retinopathy in Participants Aged 40 Years and Older in the Fasting Cohort and Without Diabetes, NHANES 2005-2008

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|

| HbA1c | 1.50 (0.82, 2.74) | 0.1778 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 1.39 (1.04, 1.85) | 0.0267 |

| Female | Ref | |

| Age | 1.03 (1.01, 1.05) | 0.0203 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Caucasian | Ref | |

| African American | 1.74 (0.97, 3.11) | 0.5376 |

| Mexican American | 0.93 (0.52, 1.64) | 0.7881 |

| Other | 1.49 (0.67, 3.32) | 0.3233 |

| HOMA-IR | 1.09 (1.03, 1.16) | 0.0030 |

| HOMA-IR | ||

| <3 (n=1258) | Ref | |

| 3-5 (n=388) | 1.49 (0.73, 2.69) | 0.3038 |

| >5 (n=268) | 1.64 (1.03, 2.62) | 0.0393 |

HbA1c = glycated hemoglobin, HOMA-IR = homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance

Discussion

In a representative sample of the United States population aged 40 years and older, incident retinopathy was present in 9.4% of patients without diabetes, and these lesions were directly related to HOMA-IR but independent of HbA1c. Patients within the highest category of insulin resistance were 64% more likely to have retinopathy compared to those in the lowest one, a finding that is clinically significant. Although individuals with retinopathy were older than those without retinopathy, HOMA-IR was an independent risk factor for retinal lesions after controlling for HbA1c in those without diabetes and HbA1c <6.5%. Background retinopathy is common in hypertension, but MABP was similar between groups. Retinopathy was more common in males than females in this cohort, a finding that has been demonstrated previously6. The retina is intrinsically responsive to insulin7, and insulin resistance in diabetes is associated with increased retinal inflammation8,9. Therefore, underlying molecular mechanisms linking local retinal insulin resistance to retinal dysfunction are plausible. The observations suggest that disrupted insulin signals – instead of outright hyperglycemia – may initiate retinal microvascular damage in diabetes and related diseases. The DCCT found that no lower glucose threshold short of normoglycemia exists for diabetic retinopathy1. However, insulin resistance could be an early driver of DR in those without overt hyperglycemia. The incidence of retinopathy in populations without diabetes has been described elsewhere. For example, patients without diabetes had a 14.2% cumulative incidence of retinopathy over 15 years in the Beaver Dam Eye Study10. The retinal lesions in this group were associated with older age, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease. However, the Beaver Dam Eye Study did not investigate the role of insulin resistance on retinopathy in the cohort without diabetes, which is the focus of the present study. The strengths of this study include high quality data collection from the CDC, independent and unbiased grading of fundus photos, and the use of a highly validated measure of insulin resistance. A limitation of this study is the inability to identify patients who previously had diabetes and developed microvascular lesions but currently are in remission, or those who received health advice and made significant lifestyle changes that affected retinal health. However, our inability to identify such patients probably did not exert a large influence on our findings since remission rate of threshold hyperglycemia in adults is estimated to be 1.6% in 7 years11. Another limitation of this study is the inability for NHANES to account for daily fluctuations in glycemia due to its cross-sectional survey design. Daily fluctuations in glucose have been shown to have some relationship to retinopathy, however, short term measures of glycemic control are less predictive of retinopathy than long-term glycemic control as measured by HbA1c12. Although this analysis is limited by the cross-sectional survey design of the NHANES dataset, further investigation of these findings could help clarify the mechanisms of visual loss in diabetes.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Janet McGill for her expert advice and the Centers for Disease Control for providing the dataset. YKB is the guarantor of the work and had full access to the data.

Funding: NIH/NEI EY025269 (RR), NIH/NIDDK T32DK007120 (YB), Career Development Award from Research to Prevent Blindness (RR), Horncrest Foundation Support (RR), UMKC School of Medicine Sarah Morrison Research Award (YB).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None to report for any author

References

- 1.The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. The relationship of glycemic exposure (HbA1c) to the risk of development and progression of retinopathy in the diabetes control and complications trial. Diabetes. 1995;44(8):968–983. doi: 10.2337/diab.44.8.968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rajagopal R, Bligard GW, Zhang S, Yin L, Lukasiewicz P, Semenkovich CF. Functional deficits precede structural lesions in mice with high-fat diet–induced diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes. 2016;65(4):1072. doi: 10.2337/db15-1255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.NHANES 2007-2008 Questionnaires, Datasets, and Related Documentation. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control, National Center for Health Statistics; [accessed 2018 Jun 29]. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/continuousnhanes/default.aspx?BeginYear=2007 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study Research Group. Grading diabetic retinopathy from stereoscopic color fundus photographs—an extension of the modified airlie house classification: ETDRS report number 10. Ophthalmology. 1991;98(5, Supplement):786–806. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(13)38012-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985;28(7):412–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ozawa G, MAB Jr, Adams AJ. Male–female differences in diabetic retinopathy? Curr Eye Res. 2015;40(2):234–246. doi: 10.3109/02713683.2014.958500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reiter CEN, Wu X, Sandirasegarane L, Nakamura M, Gilbert KA, Singh RSJ, Fort PE, Antonetti DA, Gardner TW. Diabetes reduces basal retinal insulin receptor signaling: reversal with systemic and local insulin. Diabetes. 2006;55(4):1148–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee J-J, Wang P-W, Yang I-H, Huang H-M, Chang C-S, Wu C-L, Chuang J-H. High-fat diet induces toll-like receptor 4-dependent macrophage/microglial cell activation and retinal impairment. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56(5):3041–3050. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-16504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiang Y, Thakran S, Bheemreddy R, Ye E-A, He H, Walker RJ, Steinle JJ. Pioglitazone normalizes insulin signaling in the diabetic rat retina through reduction in tumor necrosis factor α and suppressor of cytokine signaling 3. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(38):26395–26405. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.583880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klein R, Myers CE, Lee KE, Klein BEK. The 15-year cumulative incidence and associated risk factors for retinopathy in nondiabetic persons. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128(12):1568–1575. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karter AJ, Nundy S, Parker MM, Moffet HH, Huang ES. Incidence of remission in adults with type 2 diabetes: the diabetes & aging study. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(12):3188–3195. doi: 10.2337/dc14-0874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsu C-R, Chen Y-T, Sheu WH-H. Glycemic variability and diabetes retinopathy: a missing link. J Diabetes Complications. 2015;29(2):302–306. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2014.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]