Abstract

DNA damage is one of the most consistent cellular process proposed to contribute to aging. The maintenance of genomic and epigenomic integrity is critical for proper function of cells and tissues throughout life, and this homeostasis is under constant strain from both extrinsic and intrinsic insults. Considering the relationship between lifespan and genotoxic burden, it’s plausible the longest-lived cellular populations would face an accumulation of DNA damage over time. Tissue-specific stem cells are multipotent populations residing in localized niches and are responsible for maintaining all lineages of their resident tissue/system throughout life. However, many of these stem cells are impacted by genotoxic stress. Several factors may dictate the specific stem cell population response to DNA damage, including the niche location, life history, and fate decisions after damage accrual. This leads to differential handling of DNA damage in different stem cell compartments. Given the importance of adult stem cells in preserving normal tissue function during an individual’s lifetime, DNA damage sensitivity and accumulation in these compartments could have crucial implications for aging. Despite this, more support for direct functional effects driven by accumulated DNA damage in adult stem cell compartments is needed. This review will present current evidence for the accumulation and potential influence of DNA damage in adult tissue-specific stem cells and propose inquiry directions that could benefit individual healthspan.

Keywords: Adult stem cells, tissue specific stem cells, aging, DNA damage, DNA repair, mutations

Introduction

The field of aging research has been rapidly advancing in recent decades and with it our understanding of its complexity. As a result, our knowledge on the physiological and molecular hallmarks of aging has greatly expanded (Lopez-Otin et al. 2013). Concomitantly, many theories have been proposed to explain what drives these changes (Vina, Borras, and Miquel 2007; Finch and Kirkwood 2000), including free radicals (Harman 1956), semi-stochastic damage accumulation (Gladyshev 2013), immuno-senescence (Franceschi, Bonafe, and Valensin 2000), metabolism and growth (McCay, Crowell, and Maynard 1989), antagonistic pleiotropy (Williams 1957) and others. Despite the increasing data describing aging phenotypes, our understanding of what drives aging remains unclear. Among the many theories, somatic DNA damage has long been a suspected driver of aging (Kirkwood 1977; Szilard 1959) and is extensively investigated (reviewed in Moskalev et al. 2013). Within the soma, adult stem cells are especially relevant to lifelong tissue maintenance as they have the capacity to generate somatic cell lineages. This functional capacity of the tissue specific stem cells is altered with age (Table 1), via both extrinsic and intrinsic factors. One potential driver of this change could be derived from the inability to maintain genomic integrity. This is particularly relevant to the stem cell compartment as their role in the organism is to maintain and restore the function of the tissue or system they belong to. To maintain homeostasis and to repair injured systems, these cells differentiate into all cells composing the tissue / system (Wagers and Weissman 2004); thus, any change to the genome would be inherited by a multitude of daughter cells. Damage passed to the differentiated progeny could exponentially magnify the impact of the genotoxic damage by amplification in differentiated cells. Second, stem cells possess the unique ability to self-renew, i.e., to proliferate and generate more of themselves (Wagers and Weissman 2004). As such, a mutation could propagate within the stem cell compartment itself. In some cases, these mutations may either lead to loss of the already rare stem cells or worse, confer a selective advantage to stem cells that harbor them, leading to domination of mutated clones (Jaiswal et al. 2014). Moreover, the inherent self-renewal capability of stem cells combined with their undifferentiated state places them in functional proximity to cancer cells (Malta et al. 2018). Stem cells are therefore more susceptible to transformation resulting from the accumulation of mutations (Tomasetti and Vogelstein 2015; Jaiswal et al. 2014; Salk, Fox, and Loeb 2010). Finally, the long-term maintenance of tissue homeostasis depends on the ability of somatic stem cells to replace the effector cells within the system in a consistent manner. In that regard, the attrition of stem cell genomic integrity would inevitably result in a loss of tissue homeostasis either in the direction of hyperproliferation e.g. cancer and fibrosis, or hypo-proliferation.

Table 1.

Evidence for age-related accumulation of DNA damage, or reduced DNA-damage response in stem cells

| Stem cell | Species | Type of Damage/DDR | Observation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hematopoietic (HSC) | Mouse | γH2AX foci | Accumulate in HSCs | (Rossi et al. 2007; Flach et al. 2014) |

| Strand breaks | Accumulate in HSCs | (Beerman et al. 2014) | ||

| 53BP1 and p-CHK1 | No accumulation | (Flach et al. 2014) | ||

| γH2AX foci and Strand breaks | Accumulate in HSCs (compensated by repair upon stress) | (Moehrle et al. 2015) | ||

| Strand breaks. ROS | Accumulate in HSPCs | (Porto et al. 2015) | ||

| pKap1 | Increased in HSC | (Anjos-Afonso et al. 2016) | ||

| γH2AX and 53BP1 foci, Strand breaks Various DDR pathways |

Accumulate in HSCs Diminished ATM activity resulting in reduced apoptotic priming |

(Gutierrez-Martinez et al. 2018) | ||

| Human | mtDNA mutations | Accumulate in bone marrow CD34+ cells | (Shin et al. 2004) | |

| mtDNA mutations | Accumulate in mobilized CD34+ | (Ogasawara et al. 2005) | ||

| γH2AX foci DSB repair capacity |

Accumulate in mobilized CD34+ and bone marrow CD34+CD38- Reduced with age in mobilized CD34+ but not in bone marrow HSPCs |

(Rube, Fricke, et al. 2011) | ||

| Microsatellite instability MMR component MLH1 |

Increases in bone marrow CD34+ Reduced expression in a subset of CD34+ HSPCs |

(Kenyon et al. 2012) | ||

| mtDNA mutations | Accumulate with age in mobilized CD34+ | (Yao et al. 2013) | ||

| Somatic mutations | Accumulate in circulating Lin-CD34+CD38− | (Welch et al. 2012) | ||

| Somatic mutations | Accumulate in HSCs | (Lee-Six et al. 2018) | ||

| Somatic mutations | Accumulate in bone marrow CD34+CD38−CD45RA−CD90+CD49f+ (HSC) | (Osorio et al. 2018) | ||

| Muscle (MuSC) | Mouse | Strand breaks and yH2AX foci | Accumulates with age | (Sinha et al. 2014) |

| yH2AX foci | No significant DSB accumulation with age | (Cousin et al. 2013) | ||

| yH2AX foci, Strand breaks | Age-related decline in mitotic catastrophe damage response associated with accumulation of yH2AX foci | (Liu et al. 2018) | ||

| yH2AX foci, Senescence | Aged MuSC are prone to enter cellular senescence with accumulation of yH2AX foci | (Sousa-Victor et al. 2014) | ||

| Human | Mutations | Accumulate with age | (Franco et al. 2018) | |

| Intestinal (ISC) | Drosophila | γH2AX foci, 8-oxo-dG | Accumulates with age | (Park et al. 2012; Na et al. 2013) |

| Centrosome amplification | Accumulates with age | (Park et al. 2014) | ||

| ATR dependent DDR | Increased basal and inducible activity | (Park et al. 2015) | ||

| Genomic modifications, mutations, deletions | Accumulate in ISCs, leading to spontaneous neoplasia | (Siudeja et al. 2015) | ||

| Various DDR pathways γH2Av foci, transposable element expression (Gypsy-TRAP) | Age-related decline DDR (correlated with Piwi regulation) Increased with age | (Sousa-Victor et al. 2017) | ||

| Mouse | IR DDR response | Reduced with age | (Martin et al. 1998; Martin, Kirkwood, and Potten 1998) | |

| DDR gene expression | increased with age | (Moorefield et al. 2017) | ||

| Human | mtDNA mutations | Accumulate with age | (Taylor et al. 2003) | |

| mtDNA mutations, clonal expansion | Accumulate with age | (Greaves et al. 2014; Greaves et al. 2006) | ||

| Mutations | Accumulate with age | (Blokzijl et al. 2016) | ||

| Mesenchymal (MSC) ** | Mouse | γH2AX foci | Increased in osteoprogenitors | (Kim, Chang, et al. 2017) |

| Human | yH2AX foci, oxidative damage (DCFDA) | Increased with age in dental pulp MSCs | (Feng et al. 2014) | |

| Strand breaks | Increased in old stromal cells | (Gnani et al. 2019) | ||

| WRN regulated DDR | Reduced WRN expression in dental pulp MSCs from old | (Zhang et al. 2015) | ||

| Neural (NSC) | Mouse | Mutation/deletions | Loss of heterozygosity | (Bailey, Maslov, and Pruitt 2004) |

| Strand breaks | No accumulation of DNA damage | (Kalamakis et al. 2019) | ||

| Mouse and Rat | Regulation of oxidative stress by Nrf2 | Age-related alterations in levels or function of Nrf2 | (Ray et al. 2018; Corenblum et al. 2016) | |

| Skin (SSC) | Mouse | Strand breaks and γH2AX foci | Accumulate in HFSCs | (Matsumura et al. 2016) |

| yH2AX foci, 8-oxo-dG | Accumulate in epSCs in a circadian dependent manner | (Solanas et al. 2017) | ||

| Germ (GSC) | C. elegans | DDR gene expression | Altered with age in oocytes | (Luo et al. 2010) |

| Mouse | DDR gene expression | Altered with age in male and female GSCs | (Zhang et al. 2006; Hamatani et al. 2004) | |

| Rat | DDR gene expression | Altered with age in sperm | (Paul, Nagano, and Robaire 2013, 2011) | |

| Human | Mutations in progeny | Increase with both parental and maternal age | (Risch et al. 1987; Kong et al. 2012) | |

| Chromosomal structural aberrations | Increase in sperm with age | (Sloter et al. 2007; Wyrobek et al. 2006; Schmid et al. 2013; Templado et al. 2011) | ||

| Chromosomal trisomy | Increase in oocytes with age | (Oliver et al. 2008; Hassold et al. 1995) (Bugge et al. 1998; Fisher et al. 1995) (Lamb et al. 1997; Lamb et al. 1996) |

||

| Strand breaks | Increase in sperm with age | (Schmid et al. 2007; Alshahrani et al. 2014) | ||

| DDR gene expression | Altered in oocytes | (Steuerwald et al. 2007; Titus et al. 2013) | ||

| γH2AX foci | Accumulates in oocytes with age | (Titus et al. 2013) | ||

DDR – DNA damage Response

Mesenchymal stromal cells are a heterogeneous cell population, and more refined populations of skeletal stem cells have been recently defined (see text for details)

Understanding the contribution of DNA damage to the aging of tissue-specific stem cells could have crucial implications for our understanding of the aging process and development of aging interventions. In this review, we present an examination of current findings on DNA damage in multiple adult stem cell compartments.

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs)

Hematopoietic stem cells are responsible for the production of all blood cells throughout life (Weissman and Shizuru 2008). While remarkably potent (Harrison 1972), HSCs undergo marked age-related changes, including increased numbers, reduced functional potential, and a shift towards intrinsic myeloid bias in both human and mouse models (Beerman et al. 2010; Pang et al. 2011). These age-related changes are also associated with altered epigenetic profiles (Beerman et al. 2013; Sun et al. 2014) and changes in metabolic potential (Ho et al. 2017), and the human HSC frequently presents with an age-associated mutation-driven clonal expansion, often preceding cancer (Shlush et al. 2014; Jaiswal et al. 2014; Welch et al. 2012).

HSCs predominantly reside in the bone marrow, and despite the hematopoietic system’s demanding cell-production burden, due to the high turnover rate of blood cells, the limited HSC population is largely quiescent with few divisions throughout an organism’s lifetime (Wilson et al. 2008; Bernitz et al. 2016). This prolonged dormancy could theoretically protect HSCs from DNA damage by reducing the incidence of replication-based errors, minimizing telomere attrition, and curtailing oxidative damage by lowering metabolic activity (reviewed in Beerman 2017). HSCs are further protected by their hypoxic niche (Suda, Takubo, and Semenza 2011; Parmar et al. 2007; Nombela-Arrieta et al. 2013), hypoxic intracellular state (Takubo et al. 2010), and reliance on glycolytic metabolism (Simsek et al. 2010). Furthermore, the unique ABC transporter profile of HSCs implies greater protection from cytotoxic insults (Tang et al. 2010; Zhou et al. 2002). Despite these buffers, it seems multiple forms of DNA damage accrue with age in HSCs of both mice and humans (Table 2). HSCs are one of the most rigorously studied stem cell compartments, but the assessment of DNA damage accumulation and how it effects the function of aging HSCs is still incomplete. Early studies examining DNA damage accumulation in mice relied on γH2AX foci detection, a proxy of DNA double-strand breaks measuring DNA damage response (DDR) (Table 2). Inclusion of additional assays such as single-cell gel electrophoresis (comet assay), and staining with pKAP1, 53BP1, and p-CHK1 have led to a general consensus that DNA damage accumulates in the aged HSC compartment. Fewer studies have been performed on human hematopoietic stem (and progenitor) cells, but regardless of collection technique (GCSF-mobilized peripheral blood, non-mobilized blood, or bone marrow aspirates), human progenitor cells also consistently display an elevated level of DNA damage in aged individuals (Table 2).

Table 2.

Evidence for DNA damage interventions in stem cells that affect the aging phenotype

| Stem cell | Species | Intervention on | Observation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hematopoietic (HSC) | Mouse | NER (Ercc1−/−) | Multilineage cytopenia, accelerated fatty replacement of bone marrow | (Prasher et al. 2005) |

| Telomere maintenance (mTR−/−) NER (XPDTTD) NHEJ (Ku80−/−) | Accelerated age-related functional decline of HSCs | (Rossi et al. 2007) | ||

| NHEJ (Lig4Y288C/Y288C) | Accelerated loss of erythropoiesis and bone marrow cellularity | (Nijnik et al. 2007) | ||

| DDR checkpoint regulation (ATRs/s) | Pancytopenia, old-like bone marrow cellularity and profile | (Murga et al. 2009) | ||

| NER (Ercc1−/Δ) | Progressive loss of HSPC number and function | (Cho et al. 2013) | ||

| NHEJ (XLF−/−) | Accelerated age-related functional decline of HSCs | (Avagyan et al. 2014) | ||

| Telomere maintenance (mTerc−/− 3rd gen) | Accelerated aging accompanied by Increased DNA damage and γH2AX foci in HSCs | (Wang et al. 2014) | ||

| Telomere maintenance (TERTER/ER) | Various MDS phenotypes | (Colla et al. 2015) | ||

| Replication damage tolerance (PcnaK164R) | Progressive skewing of bone marrow progenitor populations and reduction of HSC function | (Pilzecker et al. 2017) | ||

| MMR (MSH2−/−) | Formed bone marrow with preleukemic HSCs | (Qing and Gerson 2017) | ||

| Human | Irradiation | Reduced reconstitution potential and myeloid bias of HPCs in NOG mice | (Wang et al. 2015) | |

| Muscle (MuSC) | Mouse | Spindle assembly checkpoint regulation (BubR1 hypomorphic mutation) | Accelerated sarcopenia and senescence. | (Baker et al. 2004) |

| NHEJ (Xrcc5−/− or Xrcc5+/−) | Accelerated skeletal muscle aging phenotypes (reduced MuSC function and accumulation of γH2AX foci) | (Didier et al. 2012) | ||

| NER (Ercc1−/−) | Accelerated functional decline of progenitor cells | (Lavasani et al. 2012) | ||

| GDF11 supplementation | Rejuvenated functional potential to old murine MuSCs, and reduced DNA damage | (Sinha et al. 2014) | ||

| Bmi1 upregulation | Improved muscle regeneration via oxidative stress resistance with reduction of 8-oxoG | (Di Foggia et al. 2014) | ||

| Telomere maintenance (Tertmdx) | Duchenne muscular dystrophy, activation of DDR leading to impaired differentiation | (Latella et al. 2017) | ||

| NER (Ercc1−/Δ) | Impaired function | (Takayama et al. 2017) | ||

| ROS (Pitx2/3 single and double mutant mice) | Over generation of ROS resulted in DNA damage and premature differentiation or senescence | (L’Honore et al. 2018) | ||

| Intestinal (ISC) | Drosophila | Oxidative stress (Paraquat administration) | Mimics several age-related phenomena | (Biteau, Hochmuth, and Jasper 2008) |

| CncC or Keap RNAi (NRF2 Oxidative damage response) | Accelerated age-related intestinal degeneration | (Hochmuth et al. 2011) | ||

| DDR checkpoint regulation (ATM/ATR knockdown) | Reduced ISC maintenance | (Park et al. 2015) | ||

| DDR checkpoint regulation (Chk2 KD) | Increased age-related hyperproliferation | (Nagy, Sandor, and Juhasz 2018) | ||

| Multiple DDR pathways (enterocyte specific KO) | ISC hyperproliferation, increased centrosome amplification and DNA damage accumulation | (Park et al. 2018) | ||

| Mouse | Accelerated mtDNA mutations (PolgD257A) | Accelerated ISC aging phenotype | (Fox et al. 2012) | |

| Irradiation | Reduced ISC regenerative potential but increased IR-resistance | (Booth et al. 2015) | ||

| Telomerase deficient accelerated aging (G3Terc−/−) | Impaired Gadd45a regulated DDR | (Diao et al. 2018) | ||

| Mesenchymal Stromal Cells (MSC) | Mouse | DDR checkpoint regulation (ATM−/−) | Accelerated bone aging phenotype due to altered MSC potential | (Hishiya et al. 2005) |

| DDR checkpoint regulation (p53 KO, Mdm2 conditional KO) | Altered osteogenic and osteoblast differentiation phenotype | (Wang et al. 2006; Lengner et al. 2006) | ||

| DDR checkpoint regulation (ATM−/−) | Osteoporosis due to osteoblast differentiation deficit but normal progenitor numbers | (Rasheed et al. 2006) | ||

| NER (Ercc1−/−/Ercc1−/Δ) | Accelerated osteoporosis accompanied by progenitor senescence and accumulation of DNA damage | (Chen et al. 2013; Niedernhofer et al. 2006) | ||

| DDR checkpoint regulation (ATRflox/−) | Osteoporosis, possibly due to MSC depletion | (Ruzankina et al. 2007) | ||

| Telomere maintenance (Wrn KO, Terc KO) | Impaired osteoblast differentiation and accelerated loss of bone mass | (Wang, Chen, et al. 2012) | ||

| NER (Ercc2R722W TTD model) | Accelerated age-related decline in MSC osteogenic potential and bone strength | (Nicolaije et al. 2012; Diderich et al. 2012) | ||

| Various DDR pathways (WRN KO) | Recapitulated aging phenotypes upon in vitro expansion | (Zhang et al. 2015) | ||

| Rat | Wnt/β-catenin ROS induction | Induced several aging phenotypes accompanied by γH2AX foci accumulation | (Zhang et al. 2013) | |

| Sirt1 KO and OE | Sirt1 protected telomere DNA damage and affected the aging phenotype | (Chen et al. 2014) | ||

| Human | Irradiation | Reduced stemness accompanied by ROS (DCFDA) and γH2AX foci accumulation in vitro | (Hou et al. 2013) | |

| Oxidative stress (H2O2) | Induced cellular senescence in MSCs in vitro | (Borodkina et al. 2014) | ||

| Antioxidants induced DNA damage | Induced cellular senescence in MSCs in vitro | (Kornienko et al. 2019) | ||

| MMR (miR675) | Accelerated MSC transformation in vitro | (Lu et al. 2019) | ||

| Neural (NSC) | Mouse | DDR checkpoint regulation (ATM−/−) | Reduced proliferation/survival of NSCs | (Allen et al. 2001; Wong et al. 2003) |

| NHEJ (XRCC4 KO, p53 KO) | Predisposed NSPCs to medulloblastoma | (Yan et al. 2006) | ||

| p16INKArf modulation | Altered proliferative profile of NSCs | (Nishino et al. 2008) | ||

| mtDNA mutatagenesis (Polg mutation) | Disrupted NSC quiescence and accelerated aging phenotypes | (Ahlqvist et al. 2012) | ||

| Irradiation | Induced proliferative arrest (senescence) and astrocytic differentiation | (Schneider et al. 2013) | ||

| Hydroxyurea treatment | Induced proliferative arrest (senescence) with inhibited differentiation | (Dong et al. 2014) | ||

| Irradiation (neonatal) | Induced early-onset adult neurodegeneration | (Kempf et al. 2014) | ||

| Irradiation | Induces long-term impairment of NSC proliferation | (Mineyeva et al. 2018) | ||

| Irradiation (in combination with SOD mimetics and p16 KD) | Reduced neurogenesis via expression of p16INK4A, independent of ROS | (Le et al. 2018) | ||

| Mouse and Rat | Various Nrf2 manipulations | Several aging or rejuvenation phenotypes | (Ray et al. 2018; Corenblum et al. 2016) | |

| Human | Low-dose irradiation | Increased sensitivity of NSCs, elevated apoptosis and cell cycle arrest | (Acharya et al. 2010) | |

| Skin (SSC) | Mouse | DDR checkpoint (ATRflox/−) | Led to hair loss, hair graying, and progressive loss of follicle stem cells | (Ruzankina et al. 2007) |

| Irradiation DDR checkpoint regulation (ATM−/−) | Activated DDR that pushed melanocyte stem cells to differentiate Increased sensitization of melanocyte stem cells to differentiate after irradiation stress | (Inomata et al. 2009) | ||

| DDR checkpoint regulation (BRCA1−/−) | Hair follicle specific degeneration with increased γH2AX foci | (Sotiropoulou et al. 2013) | ||

| Mitochondrial DSBs (SystemicIndmito-PstI mice) Various | Hair loss, hair graying, progressive loss of follicle stem cells Various | (Pinto et al. 2017), (Luo and Murphy 2011) | ||

| Germs (GSC) | C. elegans Drosophila | I-CreI expression and irradiation | Lok kinase dependent reduced survival and loss of differentiation potential | (Ma et al. 2016) |

| Mouse | DSB repair (Brca1, MRE11, Rad51, and ATM oocyte specific KD) | Reduced fertility and oocyte survival | (Titus et al. 2013) | |

| DSB repair and signaling (ATLD1H/H) | Accelerated oocyte attrition | (Inagaki, Roset, and Petrini 2016) | ||

| Human | Recombination associated DSB (Spo11−/−, Dmc1−/− and Msh5−/−) and DDR checkpoint regulation (ATM−/−) | Reduced oocyte survival | (Di Giacomo et al. 2005) | |

| DSB repair (Brca1, MRE11, Rad51, and ATM oocyte specific KD) | Reduced fertility and oocyte survival | (Titus et al. 2013) | ||

Abbreviations: DDR – DNA damage response; DSB – Double strand break; KO – Knockout; MDS – Myelodysplastic syndrome; MMR – Mismatch repair; NER – Nucleotide excision repair; NHEJ – Non- homologous end joining; OE – Overexpression; ROS – Reactive oxygen species

Early studies examining the role of DNA damage accrual in HSCs used genetic models to ablate key DNA damage repair pathways. Mice with deficient nucleotide excision repair, homologous recombination, and non-homologous recombination pathways showed various aging HSC phenotypes under transplant paradigms (Nijnik et al. 2007; Prasher et al. 2005; Rossi et al. 2007). More recently, these observations have been expanded using other models (Table 3) and other DDR pathways such as replication damage response (Pilzecker et al. 2017) and mismatch repair (Qing and Gerson 2017). Together, the studies demostrate that varied genetic disruptions of DDR result in HSC age-related phenotypes under stress conditions and support the role of DNA damage in HSC aging phenotypes. While genetic manipulations were perfomed in mice, studies of Fanconi anemia disease indicate an analogous relationship in humans between DDR and long-term HSC maintenance (Brosh et al. 2017). Though there is strong support for the accumulation of DNA damage in the aged HSC compartment and evidence that aberrant DDR function leads to decreased functional potential, not all forms of DNA damage can be directly correlated to aging phenotypes. It is important to note that several studies have shown that neither DNA damage nor defects in repair are sufficient to drive aging of this compartment (Pugh et al. 2016; Kaschutnig et al. 2015) and that changes in DDR can be independent of the actual damage accrual (Flach et al. 2014). Several papers have also demonstrated loss of telomere maintenance and mitochondrial DNA damage are not physiological drivers of aging phenotypes (Chen et al. 2015; Samper et al. 2002; Norddahl et al. 2011; Ameur et al. 2011; Allsopp et al. 2003). Furthermore, the aged HSC compartment appears to have the capacity to recognize, respond to, and repair strand breaks once driven into cell cycle (Beerman et al. 2014; Gutierrez-Martinez et al. 2018). Taken together, this suggests that DNA damage is not the sole culprit in HSC aging. That said, forms of DNA damage, such as base mutations, have been directly associated with aging and disease progression (Table 4). By mid-age, humans acquire mutations in HSCs that are detectable at low allele frequencies in the peripheral blood. Some of these mutations confer selective advantages to the stem cells and can lead to clonal expansion defined as age-related clonal hematopoiesis (ARCH) or clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential CHIP (reviewed in Busque et al. 2018). Further, these mutations have been shown to play a role in the age-related acute myeloid leukemia (Reviewed in Short, Rytting, and Cortes 2018), myelodysplastic syndromes (Reviewed in Zhou et al. 2015; Zhou et al. 2013), and atherosclerosis (Fuster et al. 2017).

Table 3.

Disease models associated with both aging and DNA damage in stem cells

| Stem cell | Species | Aging/longevity phenotype | Observation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hematopoietic (HSC) | Human | Fanconi anemia | Progressive and accelerated bone marrow failure and AML onset | (Reviewed in Brosh et al. 2017) |

| Muscle (MuSC) | Mouse | Duchenne muscular dystrophy (Mdx) | Accelerated muscle wasting accompanied by increased 8-oxoG in MuSCs | (Di Foggia et al. 2014) |

| Intestinal (ISC) | Mouse | ATM and telomerase deficient accelerated aging | Increased apoptosis, p53 activation and anaphase bridges | (Wong et al. 2003) |

| Mesenchymal (MSC) | Mouse | Werner syndrome and HGPS (Lmna mutant combined with Wrn KO) | Accelerated MSC aging accompanied by accumulation of γH2AX/53BP1 foci | (Wu et al. 2018) |

| Trichothiodystrophy (TTD) (Ercc2R722W) | Defective NER | (Diderich et al. 2012) | ||

| Human and mouse | Werner syndrome | WRN regulates MSC heterochromatin stability | (Zhang et al. 2015) | |

| Human | Werner syndrome | Accelerated in vitro MSC cellular senescence caused by telomerase deficiency | (Cheung et al. 2014) | |

| Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome (HGPS) | MSCs differentiated in vitro from HGPS derived iPSCs display increased γH2AX foci and reduced stress fidelity | (Zhang et al. 2011) | ||

| Skin (SSC) | Mouse | Accelerated skin aging by Tap63 KO | Accelerated accumulation of γH2AX foci in the hair follicle sheath | (Su et al. 2009) |

| Human | Photoaging (UV damage) | Reduction in keratinocyte progenitors in photoaged skin | (Kwon et al. 2008) | |

| Xeroderma Pigmentosum | Genetic correction of epidermal stem cells is beneficial | (Rouanet et al. 2013) | ||

Table 4.

Evidence for the involvement of stem cell DNA damage in age-related diseases

| Stem cell | Species | Age-related disease | Observation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hematopoietic (HSC) | Mouse | Atherosclerosis | Lipoprotein receptor–deficient (Ldlr−/−) mice chimeric with Tet2 mutant HSCs displayed clonal expansion and increased atherosclerosis | (Fuster et al. 2017) |

| Human and mouse | MDS | Multiple | (Reviewed in Zhou et al. 2015; Zhou et al. 2013) | |

| AML | Multiple | (Reviewed in Short, Rytting, and Cortes 2018) | ||

| Intestinal (ISC) | Drosophila | Cancer | Age-related somatic genomic modifications in ISCs lead to spontaneous neoplasia | (Siudeja et al. 2015) |

| Mouse | Colorectal Cancer | ISCs are sensitive to alkylation-induced DNA damage, leading to hyperproliferation and transformation | (Kim et al. 2016) | |

| Bcl-2 protects ISCs from IR-induced apoptosis and is also involved in adenoma development | (van der Heijden et al. 2016) | |||

| Loss of tumor-suppressor in ISCs leads to cancer via DNA damage accumulation | (Myant et al. 2017) | |||

| Various | Colorectal cancer | Various | Reviewed in (Testa, Pelosi, and Castelli 2018) | |

| Skin (SSC) | Mouse | Basal cell carcinoma | Hedgehog signaling induced carcinoma only acted via stem cells | (Sanchez-Danes et al. 2016) |

| Squamous and basal cell carcinoma | Various | Reviewed in (Sotiropoulou and Blanpain 2012) | ||

| Neuronal (NSC) | Mouse | Medulloblastoma | NHEJ deficiency in NSPCs predisposes to cancer | (Yan et al. 2006) |

| Various brain cancer types | Combination of genomic deletions caused brain tumors from NSCs but not astrocytes | (Jacques et al. 2010) | ||

| Brain cancer | Recurrent DSB sites in NSCs promote oncogenic translocations | (Schwer et al. 2016) | ||

| Neuroblastoma | Recurrent DSB sites in NSCs occur near tumor-suppressor genes | (Wei et al. 2016), (Wei et al. 2018) | ||

| Human | Glioblastoma | Constitutive DDR allows glioblastoma stem cells to resist IR | (Carruthers et al. 2018) | |

| Medulloblastoma-conditioned media | Increases sensitivity to DNA damage and oxidative stress in NSCs | (Sharma et al. 2016) | ||

| Mesenchymal (MSC) | Human | Malignant transformation | Accelerated by miR675 regulated MMR dysfunction | (Lu et al. 2019) |

| Germ (GSC) | Human | Testicular spermatocytic seminoma | Multiple | (Romano et al. 2016) |

AML – Acute myeloid leukemia; MDS – Myelodysplastic syndrome

Satellite Cells / Muscle stem cells

Muscle stem cells, most commonly referred to as satellite cells, reside in the skeletal muscle tissue below the lamina surrounding the muscle fibers (Sacco et al. 2008). These largely quiescent adult stem cells facilitate the regeneration of skeletal muscle through differentiation into multinucleated myofibers. Loss of muscle mass with age correlates with an overall decline in function, potential, and numbers of satellite cells (Table 1). Epigenetic alterations, including histone modifications and DNA methylation, have been associated with satellite cell aging (Bigot et al. 2015; Liu et al. 2013; Schworer et al. 2016) and may also contribute to their age-associated dysfunction.

One of the first reported examinations of age-related decline of satellite cells did not see an accumulation of strand breaks (Cousin et al. 2013). To the contrary, more recent evidence has shown increased levels of DNA damage in satellite cells isolated from aged mice (Sinha et al. 2014; Liu et al. 2018) (Table 2). Similarly, in humans, functional impairment of old satellite cells was associated with loss of genomic stability (Franco et al. 2018). Additionally, genetic manipulation of key DDR genes leads to various muscle stem cell defects that mirror aging phenotypes (Table 3). For example, compromising nucleotide excision repair by manipulation of ERCC1 resulted in accelerated satellite cell functional decline (Lavasani et al. 2012; Takayama et al. 2017). Similarly, interference with the non-homologous end-joining process by XRCC manipulation resulted in acceleration of muscle aging and reduced satellite cell function (Didier et al. 2012).

Interestingly, geriatric mice, over 28 months old, exhibit senescent satellite cells (Sousa-Victor et al. 2014); as senescence is often coupled with DNA damage, this further provides indirect support for DNA damage accrual in this compartment. This transition to senescence (presumably after accumulation of DNA damage) is in contrast to HSCs which have been shown to differentiate (Wang, Sun, et al. 2012), attempt to repair the accrued damage (Beerman et al. 2014), or undergo apoptosis (Gutierrez-Martinez et al. 2018) but interestingly provided a therapeutic target. After clearance of senescent cells, through induced p16INK4a-dependent apoptosis (Baker et al. 2011) or restored autophagy (Garcia-Prat et al. 2016) the aged satellite cell population had significantly improved function. In addition, treatment with the antioxidant Trolox, which again may act by mitigating DNA damage, was also demonstrated to improve aged satellite cell function by attenuating a transition from quiescence to senescence (Sousa-Victor et al. 2014). Heterochronic parabiosis studies, where mice of different ages share blood circulation, also demonstrated improved function of the aged muscle (Conboy et al. 2005; Sinha et al. 2014) and one study examined DNA damage after heterochronic parabiosis and saw decreased pH2Ax-foci in satellite cells from aged mice exposed to the young systemic environment (Sinha et al. 2014). Thus, muscle stem cells appear to be amenable to interventions, and indeed many aging phenotypes have been reversed or mitigated in experimental settings; highlighting the potential restoration of function in aged satellite cells, associated with the clearance of DNA damage.

Intestinal stem cells (ISCs)

Intestinal stem cells give rise to every cell in the intestinal epithelium, a tissue with an exceptionally high turn-over (Hu et al. 2013), similar to the hematopoietic system. ISCs reside within intestinal crypts (Gervais and Bardin 2017) and their location and cell-cycle status appear directly correlated with their function. The active population of ISCs is typically referred to as crypt base columnar (CBC) cells reside at the base of the crypt and replicate to maintain homeostasis of the rapidly replaced cells of the intestinal epithelium. A second population of ISCs, located at the +4 crypt position, remain largely quiescent (Tian et al. 2011; Yan et al. 2012) and become active under stress conditions (Takeda et al. 2011; Tian et al. 2011). A large fraction of the published research on ISCs is generated using Drosophila melanogaster (Tables 2–5); however, recent studies in the murine system have found species-specific aging phenotypes. For instance, studies in Drosophila show an increase in ISC numbers with age (Martin et al. 1998; Biteau, Hochmuth, and Jasper 2008), but aging in mouse models is associated with maintained (Nalapareddy et al. 2017) or decreased ISC numbers (Mihaylova et al. 2018; Igarashi et al. 2019). However, in both aging is associated with a functional decline (Biteau, Hochmuth, and Jasper 2008; Choi et al. 2018; Cui et al. 2019; Igarashi et al. 2019; Mihaylova et al. 2018; Nalapareddy et al. 2017).

Table 5.

Evidence for longevity phenotypes or interventions that influence DDR or DNA integrity in stem cells

| Stem cell | Species | Aging/longevity phenotype | Observation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intestinal (ISC) | Drosophila | Metformin longevity model | Improved aged ISC function with reduced DNA damage | (Na et al. 2013) |

| Mouse | Caloric Restriction | Increased DNA damage protection in ISCs | (Yousefi et al. 2018) | |

| Mesenchymal (MSC) | Rat | In vitro treatment with old rat serum | Accelerated in vitro accumulation of γH2AX foci | (Zhang, Wang, and Tan 2011) |

| Neuronal (NSC) | Mouse | CR | Reduces inflammation in SVZ and neurogenesis decline | (Apple et al. 2019) |

| Rat | High-intensity exercise | Improves adult neurogenesis | (Nokia et al. 2016) | |

| Germ (GSC) | Mouse | CR | Prevention of age-related aneuploidy | (Selesniemi et al. 2011) |

ISCs reside within a tissue that is continuously exposed to chemical threats which naturally puts them at risk for DNA insults. In addition, the constitutively mitotically active subpopulation of ISCs is under constant replicative stress which could be aggravated by putative exposure to external stressors. Examination of both the mitochondrial and nuclear genome demonstrate evidence of age-associated DNA damage accumulation (Table 2). The DDR of ISCs may also undergo a decrease in potency (Sousa-Victor et al. 2017; Martin et al. 1998; Martin, Kirkwood, and Potten 1998), while displaying increased basal activity (Moorefield et al. 2017). These observations are likely most relevant to the quiescent ISC subpopulation (Yan et al. 2012), as active ISCs respond to most non-physiological levels of genotoxicity with cell death (Otsuka et al. 2018). This is similar to the increased propensity of more committed hematopoietic progenitor cells to undergo apoptosis as compared to HSCs (Guiterrez-Martinez et al 2018). This suggests maintenance of the quiescent stem cell population is vital for the long-term maintenance of the gut epithelium. Models inducing DNA damage in ISCs has been shown to mimic several aging phenotypes (Table 3), including the known age-related colorectal cancer (Table 5). Interestingly, ISCs during the aging process, like HSCs, seem to be at a risk to undergo clonal expansion (Lopez-Garcia et al. 2010) which has been demonstrated to be possible following K-Ras mutagenesis and could predispose for cancer (Snippert et al. 2014; Gierut et al. 2015).

Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs)

Mesenchymal stromal cells are a heterogenous population of stem, and likely, progenitor cells which can give rise to bones, muscle, fat, cartilage, fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and stroma (Chan et al. 2018) often referred to as mesenchymal stem cells. Recently, a more defined population of skeletal stem cells (SkSC) that can generate bone, cartilage and stromal tissue have been characterized in both mice (Chan et al. 2015) and humans (Chan et al. 2018); however, limited information is available about the DNA damage on this refined population, so we will discuss data generated on the more heterogeneous MSC compartment.

MSCs undergo reported phenotypical changes with age but some of these may be complicated given the heterogeneity of the populations, leading to alternative conclusions on aging phenotypes (Table 1) (Sethe, Scutt, and Stolzing 2006), and most functional analysis is performed ex vivo. Examination of DDR after exogenous damage induction was more robust in early-passage MSCs compared to late-passage MSCs (Wu et al. 2017) suggesting an “aging” defect in damage response. Increased passaging of MSCs leads to accumulation of DNA damage and mutation accrual and ultimately senescence – suggesting replication stress significantly contributes to these defects (Kim, Rhee, et al. 2017; Alves et al. 2010; Hare et al. 2016; Yu et al. 2018; Galderisi et al. 2009). Recently, direct evidence of DNA damage accumulation has also been shown in aged human MSCs, where strand break accrual was accompanied by elevated ROS levels - but not increased 8- oxo- dG staining (Gnani et al. 2019). This increased damage was also associated with a decline of MSC potential (measured by colony forming assays) and decreased osteogenic lineage differentiation (Gnani et al. 2019).

Manipulation of DNA damage repair or response pathways in MSCs has frequently resulted in accelerated aging phenotypes (Table 3), mostly through demonstration of osteoporosis and bone density loss in mice. However, a direct link between DNA damage in MSCs and any human age-related disease has yet to be reported (Table 5). This is surprising considering that intrinsic MSC dysfunction has been linked to osteoporosis (Pino, Rosen, and Rodriguez 2012), chronic inflammation (Miranda et al. 2019), arthritis (Barcia et al. 2015), and osteosarcoma (Walkley et al. 2008). Still, these data may be confounded by the heterogeneous nature of these analyzed populations, and novel insight into DNA damage accrual of SkSC and evaluation of their contribution to these aging phenotypes will likely be forthcoming.

Neuronal stem cells (NSCs)

Neuronal stem cells give rise to all major cell types in the adult brain including neurons, astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and glial cells (Gage and Temple 2013). NSCs reside in two distinct niches: the sub-ventricular zone of the lateral ventricles and the sub-granular zone of the hippocampus (Gage and Temple 2013). They contribute to the maintenance of neural tissue throughout adulthood and also provide plasticity for the generation of new structures required for learning and memory. In rodents, aging is accompanied by decreased neurogenesis by resident stem and progenitor cells (Kuhn, Dickinson-Anson, and Gage 1996). In mice, there is also a sharp age-related decrease in the total number of NSCs in the ventricular-subventricular zone (Kalamakis et al. 2019; Shook et al. 2012; Ahlenius et al. 2009). This significant decline is already apparent in mid-aged brains 7–12 months with only a modest further reduction occurring over the following year (Shook et al. 2012; Kalamakis et al. 2019). A significant loss of quiescent hippocampal NSCs is also seen between one- and 24-month-old mice (Encinas et al. 2011).

Data on age-associated DNA damage accumulation in NSCs is sparse and at times contradictory. A recent study has found no significant age-associated accumulation of DNA damage in either active or quiescent NSCs, as detected by the comet assay. Further, similar functional potency was observed in NSCs isolated from young and aged mice (Kalamakis et al. 2019). However, loss of chromosomal heterozygosity (suggestive of DNA damage) was observed in almost all neurospheres derived from aged neural stem and progenitor cells (NSPCs) generated from C57Bl/6 × DBA/2 hybrid mice (Bailey, Maslov, and Pruitt 2004). Further, seminal work assaying chromosomal architecture in cycling NSPCs, demonstrated that replication stress introduces recurrent DSB clusters in key genes regulating brain functions (Wei et al. 2016). These fragile sites are hot spots for chromosomal rearrangement events and may serve as a mechanism contributing to the somatic diversity of brain as described by McConnell et al. (2013). Thus, NSCs must balance the generation of genetic diversity contributing to short-term memory and learning (Wei et al. 2016) against maintaining the genomic fidelity of the NSC pool. It has been suggested that a subset of normally quiescent NSCs permanently exit the stem cell pool once they become activated (Encinas et al. 2011) in order to protect against a long term accumulation of DNA damage in this compartment.

Models that introduce DNA damage in the brain reproduce several aging phenotypes (Table 3), largely recapitulating aberrant differentiation potential. In young NSCs, irradiation leads to robust induction of DDR, correlated with loss of stem cell markers and differentiation towards astrocytes (Schneider et al. 2013). Another model of damage induction utilizing Polg disruption, leads to mtDNA mutagenesis and also loss of NSC self-renewal (Ahlqvist et al. 2012). While these studies again support the role of differentiation to eliminate the potentially damaged NSCs from the stem cell pool (similar to HSCs and ISCs), the majority of these studies were only performed on young NSCs and are analyses of significant extrinsic perturbations of the DNA integrity. It is yet to be fully established how more endogenous stimuli and physiologic aging may affect the fidelity of DNA and the functional potential of NSCs.

While reduced functional potential of aged NSCs could be a direct driver of dementia and Parkinson’s, there is a little evidence linking DNA damage in NSCs to common age-related diseases (Table 4). For instance, low-dose irradiation induction of an Alzheimer’s-like phenotype in mice did not act through NSCs (Kempf et al. 2016) and NSPCs are less prone to apoptosis than their progeny (Kashiwagi et al. 2018), similar to aforementioned stem cells. However, murine models may not fully recapitulate Alzheimer’s phenotypes, and the possible connection between damage and disease remain to be comprehensively examined.

Skin stem cells (SSCs)

Skin stem cells also often refer to a heterogenous population of cells residing in various locations in the skin including the hair follicles, interfollicular space, and sebaceous glands (Blanpain and Fuchs 2006). SSCs generate multiple lineages of skin cells during both regular maintenance and regeneration following an insult (such as a skin wound) (Fuchs 2008; Mascre et al. 2012). These cells are typically classified as either epidermal stem cells (EpSC) hair follicle stem cells (HFSC), or melanocyte stem cells (MeSC). During aging, SSCs undergo functional decline that varies based on subtype and exposure to external factors (Table 1). In the absence of environmental insults, EpSC numbers are retained with age, although a functional decline still occurs (Giangreco et al. 2008; Keyes et al. 2013). On the other hand, examination of HFSC antibodies in C57BL/6 mice showed an age-associated reduction in signal, with dysregulation of the stem cell signatures at regions of hair thinning and loss (Matsumura et al. 2016).

SSCs are responsible for the maintenance of a high turnover tissue but are mostly dormant (Tumbar et al. 2004), and potentially derive similar protections from DNA damage during quiescence as HSCs. However, the proximity of the skin to the atmosphere may subject SSCs to external insults that threaten DNA integrity, including high oxygen intake (Stucker et al. 2002), air pollutants, and UV radiation (Panich et al. 2016). The last has been shown to directly damage EpSCs in vivo at physiological doses (Ruetze et al. 2011). As an additional layer of protection against this exposure, EpSCs have a circadian-regulated timing of DNA replication, with proliferation occurring during the night (Janich et al. 2011). With aging, this tight regulation of S-phase entry is lost, and the EpSCs continue to cycle during the day when DNA is potentially exposed to UV and oxidative damage. Accordingly, aged EpSCs display high levels of 8-OHdG and γH2AX staining throughout the day, indicating elevated DNA damage (Solanas et al. 2017).

Perhaps the most intuitive link between SSC aging and DNA damage is hair graying and hair loss, both known aging phenotypes. HFSCs in the aged skin display elevated levels of damage, indicated by 53BP1, γH2AX-foci, and the comet assay; this damage accumulation is more pronounced in regions of hair graying and loss (Matsumura et al. 2016). Additionally, MeSC depletion, due to excessive differentiation driven by DNA damage, induces hair graying (Inomata et al. 2009). Hair thinning is also a common feature of progeroid syndromes such as Werner’s syndrome and Ataxia-telangiectasia (Hasty et al. 2003), both of which are driven by genomic instability again drawing connections between DNA damage and aging phenotypes. Similar loss of homeostatic function was observed after induction of DNA damage by irradiation or when using the XPDTTD/TTD progeroid mouse model (Matsumura et al. 2016). Notably, the age-associated accumulation of strand breaks in HFSCs was reported to not exclusively colocalize with telomeric DNA, suggesting the accumulation of damage foci is independent of telomere shortening (Schuler and Rube 2013).

Overall, these lines of evidence suggest DNA damage accumulation in aged skin stem cells and raises the question of how these stem cells address this burden. HFSCs, as many of the tissue specific stem cells, are more resistant to DNA damage induced apoptosis compared to more differentiated cells (Solanas et al. 2017; Gutierrez-Martinez et al. 2018). Further, both MeSCs and HFSCs commit to differentiation after significant genotoxic stress, (Inomata et al. 2009; Matsumura et al. 2016), a strategy also used by aged HSCs (Wang, Sun, et al. 2012; Wingert et al. 2016). These mechanisms could serve as a fail-safe to eliminate damaged stem cells from the niche to minimize cancer potential.

Germline stem cells (GSCs)

Germline stem cells are, by definition, not somatic or responsible for adult tissue homeostasis. However, they reside within aging organisms and may be affected by aging processes, such as DNA damage accumulation. The major downstream impact of genomic damage and mutagenesis in GSCs would manifest in the progeny or as infertility with direct consequences to the germline, but there are also instances in which accumulation of damage could affect the host soma. Unlike other stem cells, GSCs differ noticeably between the sexes. In humans, oocyte generation ceases after birth while spermatogenesis involves constant replication throughout life, greatly increasing the risk of mutagenesis due to replication errors and necessitating powerful genome maintenance strategies (Goriely and Wilkie 2012). Accordingly, spermatogenial stem cells also utilize unique DNA damage responses (Rube, Zhang, et al. 2011; Ishii et al. 2014; Ahmed et al. 2007), including constitutively active telomerase (Pech et al. 2015), similar to somatic tissue specific stem cells. In fact, telomerase is so highly active that their telomeres have been reported to elongate with age (Antunes et al. 2015). Despite such protective mechanisms, male reproductive potential declines with age (Paul, Nagano, and Robaire 2013) correlating with a decline in GSC number and function (Paul, Nagano, and Robaire 2013, 2011; Zhang et al. 2006). Notably, a study demonstrated that in mice the intrinsic spermatogenesis cellular potential exceeds the natural mouse lifespan (Ryu et al. 2006), indicating a strong influence of the niche in the aging phenotype. Despite this potential, there is evidence spermatogenial stem cells also accumulate DNA damage with age (Sloter et al. 2007; Schmid et al. 2013; Templado et al. 2011) and display altered DDR gene expression profiles (Paul, Nagano, and Robaire 2013, 2011; Zhang et al. 2006). These aberrations have been linked to both infertility (Alshahrani et al. 2014; Wyrobek et al. 2006) and mutagenesis that predisposes progeny to various types of illness (Kong et al. 2012; Goriely and Wilkie 2012). These mutations could also lead to a selective advantage of specific clones, leading to clonal expansion of spermatogenial cells (Goriely et al. 2005; Goriely et al. 2003). Interestingly, testicular germ cell tumors originate from germ cells and in the case of spermatocytic seminoma is a disease of late life (Bahrami, Ro, and Ayala 2007). This cancer, which is generally associated with deficiency in the DDR (Romano et al. 2016), exemplifies how a non-somatic stem cell can drive an aging phenotype in the adult.

Like male GSCs, it seems oocytes of many species also decline in function with age (Ge et al. 2015; Luo and Murphy 2011; Zhao et al. 2008). In humans, oocytes cease to proliferate after birth. On one hand, this protects them from replication errors; on the other, they face a unique challenge to maintain genome integrity and function for a long time in a cell arrested at meiotic prophase I (Luo and Murphy 2011). Possibly to provide the females with the optimal oocytes, a block in DNA damage repair signaling by RNF12 and HORMAD shunt damaged cells towards apoptosis opposed to repair implicating a DNA quality control mechanism that drives the dramatic reduction of total number of oocytes seen in development (Qiao et al. 2018). In the adult, quiescent oocytes display active DNA repair with highly tuned quality control mechanisms to eliminate cells when repair fails (Qiao et al. 2018; Rinaldi et al. 2017; Stringer et al. 2018; Tuppi et al. 2018). Despite this, several genes for DNA maintenance have been shown to be mis-regulated in aging human and mouse oocytes (Hamatani et al. 2004; Steuerwald et al. 2007; Titus et al. 2013). Accordingly, aged oocytes have been shown to accumulate gH2Ax-foci with age, accompanied by a decline in BRCA1, Mre11, Rad51, and ATM (Titus et al. 2013), indicating that DSB repair is especially strained. DNA damage in oocytes has been shown to directly affect their functional decline in flies (Ma et al. 2016) and the link in humans is also quite clear as aneuploidy in the embryo almost always stems from the oocyte (Nagaoka, Hassold, and Hunt 2012); with these errors consistently increasing with age (Nagaoka, Hassold, and Hunt 2012). A fascinating aspect in this field are the dynamics with which different abnormalities accumulate with age: for example, the frequency of trisomy 16 rises sharply immediately following sexual maturity (Hassold et al. 1995) in a fairly linear fashion; whereas the frequency of trisomy 21 increases slowly at first but surges later in life (Nagaoka, Hassold, and Hunt 2012). Taken together, these patterns indicate a combination of specific types of failure- such as loss of chromosome cohesion (Hunt and Hassold 2010) as well as a strong influence of the niche; they also clearly demonstrate that the aging of this system begins long before menopause and is not solely driven by oocyte depletion. This fact also opens the door for the use of model organisms where oocytes are continuously generated to study the aging of this compartment, such as worms and flies (reviewed in Luo and Murphy 2011). In mice, it has been reported that a 40% caloric restriction diet attenuates the age-related oocyte aneuploidy (Selesniemi et al. 2011). Interestingly, reduced oocyte function with age has been proposed to be driven by telomere attrition, despite their absolute lack of replicative stress (Keefe, Marquard, and Liu 2006).

Discussion

Overall, evidence suggests tissue specific stem cells accrue DNA damage during aging despite being considered protected populations (Table 2). This accumulation differs between the various stem cell compartments, and divergence could derive from stem cells’ inherent properties (e.g. DNA methylation profile, potency etc.), their functional dynamics (e.g. quiescent vs. highly proliferative), and the niche in which they reside. The complexity of how these factors interact is well exemplified in quiescent HSCs, in which decreased cycling mitigates replicative associated damage, but consequently allows for accumulation of other types of damage, as DNA damage response pathways are attenuated until cell cycle re-entry (Beerman et al. 2013). A similar concept is exemplified in the sex difference in human germ cells; both have highly tuned defense mechanisms yet accumulate DNA damage with age, but with very distinct types depending on their extremely different proliferative profile.

Despite apparent accumulation of DNA damage with age, the evidence is incomplete to definitely state damage accrual drives the aging of stem cells or the tissues they support. While disturbance of genomic integrity can mimic some stem cell aging phenotypes (Tables 3 and 4), it has yet to be demonstrated that alleviation of the damage burden results in overall extension of health or lifespan. Similarly, there is little evidence showing increased stem cell genomic fidelity in models of longevity, such as centenarians (Table 5). While DNA damage in stem cells has been repeatedly linked to age-related neoplasias (Table 5), no study so far has shown a similar connection to any other age-related diseases with the exception of HSCs in atherosclerosis (Fuster et al. 2017). Of course, some aging processes of the somatic stem cell compartment could be entirely independent of DNA damage; such as alterations in the epigenetic profile (Beerman and Rossi 2015) or proteolytic regulation (Leeman et al. 2018), or potentially combinations of these contributions- such as mutation accrual leading to loss of DNA methylation and vice versa (Xia, Han, and Zhao 2012).

Regardless of whether DNA damage in tissue-specific stem cells is a driver or passenger of aging processes, it appears some damage is inevitable. While we may be able to minimize some insults (e.g. UV exposure), other drivers of damage could be nearly impossible to prevent (e.g. replicative stress). In addition, considering the complex and acutely regulated endogenous DNA damage repair and response network, introducing exogenous improvements to this exquisitely fine-tuned pathway is a daunting task. Thus, any intervention that aims to mitigate age-related diseases driven by DNA damage in stem cells, or to serve as a rejuvenation therapy, would likely need to be applied with the underlying assumption that damage has occurred. It could perhaps be more useful to focus on targeting the downstream effects of this damage on both the stem cell population and its progeny, rather than its prevention. This would require an understanding of the tissue specific implications of said damage. For example, DNA damage in the HSC compartment leads to mutations which can lead to clonal expansion of cells bearing mutations that give them a selective advantage. Identifying and characterizing different clone-types would serve crucial in diagnosis of individuals predisposed to hematologic cancers. Age-related changes in the HSC pool could also alter the trajectory of any potential intervention. For one, undesired clonality should be avoided in a transplantation setting. On the other hand, identification of “bad” clones opens the door to investigate how to eliminate them distinctively while preserving the “good” clones”. However, we have yet to fully understand the classification between “good” and “bad” clones. A similar understanding of parallel phenomenon in other stem cell compartments would be of equal importance for any future medical treatment or intervention aimed to alleviate aging phenotypes or age-related diseases requiring a solid understanding of stem cell type-specific aging phenotypes. Thus, there are still several avenues of research to pursue to fully characterize age-associated loss of stem cell potential; ideally providing more insight into targets for improvement of overall health of each tissue/system through maintenance of stem cell function.

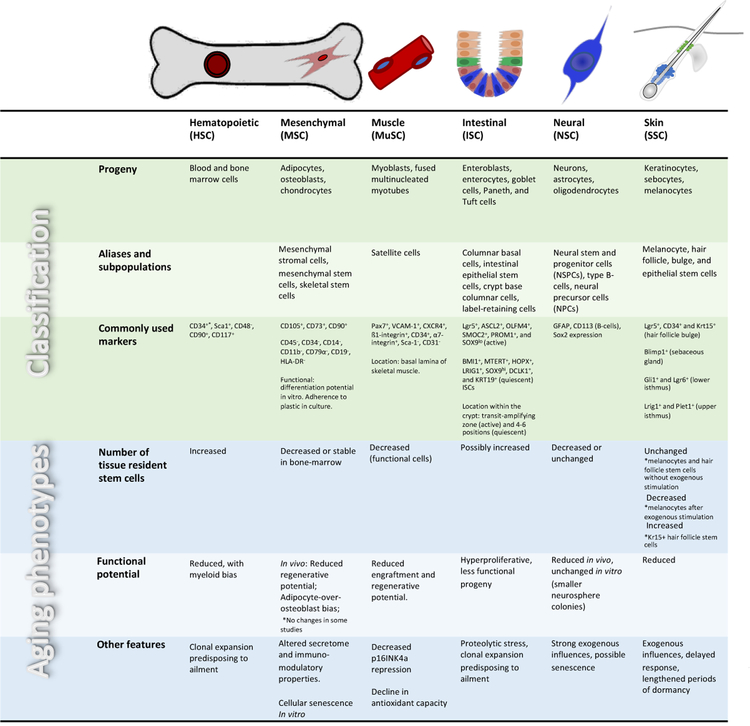

Fig. 1.

Classification and aging phenotypes of adult somatic stem cells.

* negative for mouse

** See text for references

Acknowledgements:

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health. We apologize for the inability to cite all relevant manuscripts.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

References:

- Acharya MM, Lan ML, Kan VH, Patel NH, Giedzinski E, Tseng BP, and Limoli CL. 2010. ‘Consequences of ionizing radiation-induced damage in human neural stem cells’, Free Radic Biol Med, 49: 1846–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahlenius H, Visan V, Kokaia M, Lindvall O, and Kokaia Z. 2009. ‘Neural stem and progenitor cells retain their potential for proliferation and differentiation into functional neurons despite lower number in aged brain’, J Neurosci, 29: 4408–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahlqvist KJ, Hamalainen RH, Yatsuga S, Uutela M, Terzioglu M, Gotz A, Forsstrom S, Salven P, Angers-Loustau A, Kopra OH, Tyynismaa H, Larsson NG, Wartiovaara K, Prolla T, Trifunovic A, and Suomalainen A. 2012. ‘Somatic progenitor cell vulnerability to mitochondrial DNA mutagenesis underlies progeroid phenotypes in Polg mutator mice’, Cell Metab, 15: 100–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed EA, van der Vaart A, Barten A, Kal HB, Chen J, Lou Z, Minter-Dykhouse K, Bartkova J, Bartek J, de Boer P, and de Rooij DG. 2007. ‘Differences in DNA double strand breaks repair in male germ cell types: lessons learned from a differential expression of Mdc1 and 53BP1’, DNA Repair (Amst), 6: 1243–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen DM, van Praag H, Ray J, Weaver Z, Winrow CJ, Carter TA, Braquet R, Harrington E, Ried T, Brown KD, Gage FH, and Barlow C. 2001. ‘Ataxia telangiectasia mutated is essential during adult neurogenesis’, Genes Dev, 15: 554–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allsopp RC, Morin GB, Horner JW, DePinho R, Harley CB, and Weissman IL. 2003. ‘Effect of TERT over-expression on the long-term transplantation capacity of hematopoietic stem cells’, Nat Med, 9: 369–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alshahrani S, Agarwal A, Assidi M, Abuzenadah AM, Durairajanayagam D, Ayaz A, Sharma R, and Sabanegh E. 2014. ‘Infertile men older than 40 years are at higher risk of sperm DNA damage’, Reprod Biol Endocrinol, 12: 103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alves H, Munoz-Najar U, De Wit J, Renard AJ, Hoeijmakers JH, Sedivy JM, Van Blitterswijk C, and De Boer J. 2010. ‘A link between the accumulation of DNA damage and loss of multi-potency of human mesenchymal stromal cells’, J Cell Mol Med, 14: 2729–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ameur A, Stewart JB, Freyer C, Hagstrom E, Ingman M, Larsson NG, and Gyllensten U. 2011. ‘Ultra-deep sequencing of mouse mitochondrial DNA: mutational patterns and their origins’, PLoS Genet, 7: e1002028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anjos-Afonso F, Loizou JI, Bradburn A, Kanu N, Purewal S, Da Costa C, Bonnet D, and Behrens A. 2016. ‘Perturbed hematopoiesis in mice lacking ATMIN’, Blood, 128: 2017–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antunes DM, Kalmbach KH, Wang F, Dracxler RC, Seth-Smith ML, Kramer Y, Buldo-Licciardi J, Kohlrausch FB, and Keefe DL. 2015. ‘A single-cell assay for telomere DNA content shows increasing telomere length heterogeneity, as well as increasing mean telomere length in human spermatozoa with advancing age’, J Assist Reprod Genet, 32: 1685–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apple DM, Mahesula S, Fonseca RS, Zhu C, and Kokovay E. 2019. ‘Calorie restriction protects neural stem cells from age-related deficits in the subventricular zone’, Aging (Albany NY), 11: 115–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avagyan S, Churchill M, Yamamoto K, Crowe JL, Li C, Lee BJ, Zheng T, Mukherjee S, and Zha S. 2014. ‘Hematopoietic stem cell dysfunction underlies the progressive lymphocytopenia in XLF/Cernunnos deficiency’, Blood, 124: 1622–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahrami A, Ro JY, and Ayala AG. 2007. ‘An overview of testicular germ cell tumors’, Arch Pathol Lab Med, 131: 1267–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey KJ, Maslov AY, and Pruitt SC. 2004. ‘Accumulation of mutations and somatic selection in aging neural stem/progenitor cells’, Aging Cell, 3: 391–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker DJ, Jeganathan KB, Cameron JD, Thompson M, Juneja S, Kopecka A, Kumar R, Jenkins RB, de Groen PC, Roche P, and van Deursen JM. 2004. ‘BubR1 insufficiency causes early onset of aging-associated phenotypes and infertility in mice’, Nat Genet, 36: 744–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker DJ, Wijshake T, Tchkonia T, LeBrasseur NK, Childs BG, van de Sluis B, Kirkland JL, and van Deursen JM. 2011. ‘Clearance of p16Ink4a-positive senescent cells delays ageing-associated disorders’, Nature, 479: 232–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barcia RN, Santos JM, Filipe M, Teixeira M, Martins JP, Almeida J, Agua-Doce A, Almeida SC, Varela A, Pohl S, Dittmar KE, Calado S, Simoes SI, Gaspar MM, Cruz ME, Lindenmaier W, Graca L, Cruz H, and Cruz PE. 2015. ‘What Makes Umbilical Cord Tissue-Derived Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Superior Immunomodulators When Compared to Bone Marrow Derived Mesenchymal Stromal Cells?’, Stem Cells Int, 2015: 583984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beerman I 2017. ‘Accumulation of DNA damage in the aged hematopoietic stem cell compartment’, Semin Hematol, 54: 12–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beerman I, Bock C, Garrison BS, Smith ZD, Gu H, Meissner A, and Rossi DJ. 2013. ‘Proliferation-dependent alterations of the DNA methylation landscape underlie hematopoietic stem cell aging’, Cell Stem Cell, 12: 413–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beerman I, Maloney WJ, Weissmann IL, and Rossi DJ. 2010. ‘Stem cells and the aging hematopoietic system’, Curr Opin Immunol, 22: 500–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beerman I, and Rossi DJ. 2015. ‘Epigenetic Control of Stem Cell Potential during Homeostasis, Aging, and Disease’, Cell Stem Cell, 16: 613–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beerman I, Seita J, Inlay MA, Weissman IL, and Rossi DJ. 2014. ‘Quiescent hematopoietic stem cells accumulate DNA damage during aging that is repaired upon entry into cell cycle’, Cell Stem Cell, 15: 37–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernitz JM, Kim HS, MacArthur B, Sieburg H, and Moore K. 2016. ‘Hematopoietic Stem Cells Count and Remember Self-Renewal Divisions’, Cell, 167: 1296–309 e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigot A, Duddy WJ, Ouandaogo ZG, Negroni E, Mariot V, Ghimbovschi S, Harmon B, Wielgosik A, Loiseau C, Devaney J, Dumonceaux J, Butler-Browne G, Mouly V, and Duguez S. 2015. ‘Age-Associated Methylation Suppresses SPRY1, Leading to a Failure of Re-quiescence and Loss of the Reserve Stem Cell Pool in Elderly Muscle’, Cell Rep, 13: 1172–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biteau B, Hochmuth CE, and Jasper H. 2008. ‘JNK activity in somatic stem cells causes loss of tissue homeostasis in the aging Drosophila gut’, Cell Stem Cell, 3: 442–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanpain C, and Fuchs E. 2006. ‘Epidermal stem cells of the skin’, Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol, 22: 339–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blokzijl F, de Ligt J, Jager M, Sasselli V, Roerink S, Sasaki N, Huch M, Boymans S, Kuijk E, Prins P, Nijman IJ, Martincorena I, Mokry M, Wiegerinck CL, Middendorp S, Sato T, Schwank G, Nieuwenhuis EE, Verstegen MM, van der Laan LJ, de Jonge J, Jzermans JN I, Vries RG, van de Wetering M, Stratton MR, Clevers H, Cuppen E, and van Boxtel R. 2016. ‘Tissue-specific mutation accumulation in human adult stem cells during life’, Nature, 538: 260–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth C, Tudor GL, Katz BP, and MacVittie TJ. 2015. ‘The Delayed Effects of Acute Radiation Syndrome: Evidence of Long-Term Functional Changes in the Clonogenic Cells of the Small Intestine’, Health Phys, 109: 399–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borodkina A, Shatrova A, Abushik P, Nikolsky N, and Burova E. 2014. ‘Interaction between ROS dependent DNA damage, mitochondria and p38 MAPK underlies senescence of human adult stem cells’, Aging (Albany NY), 6: 481–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosh RM Jr., Bellani M, Liu Y, and Seidman MM. 2017. ‘Fanconi Anemia: A DNA repair disorder characterized by accelerated decline of the hematopoietic stem cell compartment and other features of aging’, Ageing Res Rev, 33: 67–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bugge M, Collins A, Petersen MB, Fisher J, Brandt C, Hertz JM, Tranebjaerg L, de Lozier-Blanchet C, Nicolaides P, Brondum-Nielsen K, Morton N, and Mikkelsen M. 1998. ‘Non-disjunction of chromosome 18’, Hum Mol Genet, 7: 661–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busque L, Buscarlet M, Mollica L, and Levine RL. 2018. ‘Concise Review: Age-Related Clonal Hematopoiesis: Stem Cells Tempting the Devil’, Stem Cells, 36: 1287–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carruthers RD, Ahmed SU, Ramachandran S, Strathdee K, Kurian KM, Hedley A, Gomez-Roman N, Kalna G, Neilson M, Gilmour L, Stevenson KH, Hammond EM, and Chalmers AJ. 2018. ‘Replication Stress Drives Constitutive Activation of the DNA Damage Response and Radioresistance in Glioblastoma Stem-like Cells’, Cancer Res, 78: 5060–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan CKF, Gulati GS, Sinha R, Tompkins JV, Lopez M, Carter AC, Ransom RC, Reinisch A, Wearda T, Murphy M, Brewer RE, Koepke LS, Marecic O, Manjunath A, Seo EY, Leavitt T, Lu WJ, Nguyen A, Conley SD, Salhotra A, Ambrosi TH, Borrelli MR, Siebel T, Chan K, Schallmoser K, Seita J, Sahoo D, Goodnough H, Bishop J, Gardner M, Majeti R, Wan DC, Goodman S, Weissman IL, Chang HY, and Longaker MT. 2018. ‘Identification of the Human Skeletal Stem Cell’, Cell, 175: 43–56 e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan CK, Seo EY, Chen JY, Lo D, McArdle A, Sinha R, Tevlin R, Seita J, Vincent-Tompkins J, Wearda T, Lu WJ, Senarath-Yapa K, Chung MT, Marecic O, Tran M, Yan KS, Upton R, Walmsley GG, Lee AS, Sahoo D, Kuo CJ, Weissman IL, and Longaker MT. 2015. ‘Identification and specification of the mouse skeletal stem cell’, Cell, 160: 285–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Liu X, Zhu W, Chen H, Hu X, Jiang Z, Xu Y, Wang L, Zhou Y, Chen P, Zhang N, Hu D, Zhang L, Wang Y, Xu Q, Wu R, Yu H, and Wang J. 2014. ‘SIRT1 ameliorates age-related senescence of mesenchymal stem cells via modulating telomere shelterin’, Front Aging Neurosci, 6: 103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Bryant MA, Dent JJ, Sun Y, Desierto MJ, and Young NS. 2015. ‘Hematopoietic lineage skewing and intestinal epithelia degeneration in aged mice with telomerase RNA component deletion’, Exp Gerontol, 72: 251–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Liu K, Robinson AR, Clauson CL, Blair HC, Robbins PD, Niedernhofer LJ, and Ouyang H. 2013. ‘DNA damage drives accelerated bone aging via an NF-kappaB-dependent mechanism’, J Bone Miner Res, 28: 1214–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung HH, Liu X, Canterel-Thouennon L, Li L, Edmonson C, and Rennert OM. 2014. ‘Telomerase protects werner syndrome lineage-specific stem cells from premature aging’, Stem Cell Reports, 2: 534–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho JS, Kook SH, Robinson AR, Niedernhofer LJ, and Lee BC. 2013. ‘Cell autonomous and nonautonomous mechanisms drive hematopoietic stem/progenitor cell loss in the absence of DNA repair’, Stem Cells, 31: 511–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J, Rakhilin N, Gadamsetty P, Joe DJ, Tabrizian T, Lipkin SM, Huffman DM, Shen X, and Nishimura N. 2018. ‘Intestinal crypts recover rapidly from focal damage with coordinated motion of stem cells that is impaired by aging’, Sci Rep, 8: 10989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colla S, Ong DS, Ogoti Y, Marchesini M, Mistry NA, Clise-Dwyer K, Ang SA, Storti P, Viale A, Giuliani N, Ruisaard K, Ganan Gomez I, Bristow CA, Estecio M, Weksberg DC, Ho YW, Hu B, Genovese G, Pettazzoni P, Multani AS, Jiang S, Hua S, Ryan MC, Carugo A, Nezi L, Wei Y, Yang H, D’Anca M, Zhang L, Gaddis S, Gong T, Horner JW, Heffernan TP, Jones P, Cooper LJ, Liang H, Kantarjian H, Wang YA, Chin L, Bueso-Ramos C, Garcia-Manero G, and DePinho RA. 2015. ‘Telomere dysfunction drives aberrant hematopoietic differentiation and myelodysplastic syndrome’, Cancer Cell, 27: 644–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conboy IM, Conboy MJ, Wagers AJ, Girma ER, Weissman IL, and Rando TA. 2005. ‘Rejuvenation of aged progenitor cells by exposure to a young systemic environment’, Nature, 433: 760–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corenblum MJ, Ray S, Remley QW, Long M, Harder B, Zhang DD, Barnes CA, and Madhavan L. 2016. ‘Reduced Nrf2 expression mediates the decline in neural stem cell function during a critical middle-age period’, Aging Cell, 15: 725–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousin W, Ho ML, Desai R, Tham A, Chen RY, Kung S, Elabd C, and Conboy IM. 2013. ‘Regenerative capacity of old muscle stem cells declines without significant accumulation of DNA damage’, PLoS One, 8: e63528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui H, Tang D, Garside GB, Zeng T, Wang Y, Tao Z, Zhang L, and Tao S. 2019. ‘Wnt Signaling Mediates the Aging-Induced Differentiation Impairment of Intestinal Stem Cells’, Stem Cell Rev [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Di Foggia V, Zhang X, Licastro D, Gerli MF, Phadke R, Muntoni F, Mourikis P, Tajbakhsh S, Ellis M, Greaves LC, Taylor RW, Cossu G, Robson LG, and Marino S. 2014. ‘Bmi1 enhances skeletal muscle regeneration through MT1-mediated oxidative stress protection in a mouse model of dystrophinopathy’, J Exp Med, 211: 2617–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giacomo M, Barchi M, Baudat F, Edelmann W, Keeney S, and Jasin M. 2005. ‘Distinct DNA-damage-dependent and -independent responses drive the loss of oocytes in recombination-defective mouse mutants’, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 102: 737–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diao D, Wang H, Li T, Shi Z, Jin X, Sperka T, Zhu X, Zhang M, Yang F, Cong Y, Shen L, Zhan Q, Yan J, Song Z, and Ju Z. 2018. ‘Telomeric epigenetic response mediated by Gadd45a regulates stem cell aging and lifespan’, EMBO Rep, 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diderich KE, Nicolaije C, Priemel M, Waarsing JH, Day JS, Brandt RM, Schilling AF, Botter SM, Weinans H, van der Horst GT, Hoeijmakers JH, and van Leeuwen JP. 2012. ‘Bone fragility and decline in stem cells in prematurely aging DNA repair deficient trichothiodystrophy mice’, Age (Dordr), 34: 845–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Didier N, Hourde C, Amthor H, Marazzi G, and Sassoon D. 2012. ‘Loss of a single allele for Ku80 leads to progenitor dysfunction and accelerated aging in skeletal muscle’, EMBO Mol Med, 4: 910–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong CM, Wang XL, Wang GM, Zhang WJ, Zhu L, Gao S, Yang DJ, Qin Y, Liang QJ, Chen YL, Deng HT, Ning K, Liang AB, Gao ZL, and Xu J. 2014. ‘A stress-induced cellular aging model with postnatal neural stem cells’, Cell Death Dis, 5: e1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Encinas JM, Michurina TV, Peunova N, Park JH, Tordo J, Peterson DA, Fishell G, Koulakov A, and Enikolopov G. 2011. ‘Division-coupled astrocytic differentiation and age-related depletion of neural stem cells in the adult hippocampus’, Cell Stem Cell, 8: 566–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X, Xing J, Feng G, Huang D, Lu X, Liu S, Tan W, Li L, and Gu Z. 2014. ‘p16(INK4A) mediates age-related changes in mesenchymal stem cells derived from human dental pulp through the DNA damage and stress response’, Mech Ageing Dev, 141–142: 46–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch Caleb, and Kirkwood TBL. 2000. Chance, development, and aging (Oxford University Press: New York ; Oxford: ). [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JM, Harvey JF, Morton NE, and Jacobs PA. 1995. ‘Trisomy 18: studies of the parent and cell division of origin and the effect of aberrant recombination on nondisjunction’, Am J Hum Genet, 56: 669–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flach J, Bakker ST, Mohrin M, Conroy PC, Pietras EM, Reynaud D, Alvarez S, Diolaiti ME, Ugarte F, Forsberg EC, Le Beau MM, Stohr BA, Mendez J, Morrison CG, and Passegue E. 2014. ‘Replication stress is a potent driver of functional decline in ageing haematopoietic stem cells’, Nature, 512: 198–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox RG, Magness S, Kujoth GC, Prolla TA, and Maeda N. 2012. ‘Mitochondrial DNA polymerase editing mutation, PolgD257A, disturbs stem-progenitor cell cycling in the small intestine and restricts excess fat absorption’, Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol, 302: G914–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franceschi C, Bonafe M, and Valensin S. 2000. ‘Human immunosenescence: the prevailing of innate immunity, the failing of clonotypic immunity, and the filling of immunological space’, Vaccine, 18: 1717–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco I, Johansson A, Olsson K, Vrtacnik P, Lundin P, Helgadottir HT, Larsson M, Revechon G, Bosia C, Pagnani A, Provero P, Gustafsson T, Fischer H, and Eriksson M. 2018. ‘Somatic mutagenesis in satellite cells associates with human skeletal muscle aging’, Nat Commun, 9: 800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs E 2008. ‘Skin stem cells: rising to the surface’, J Cell Biol, 180: 273–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuster JJ, MacLauchlan S, Zuriaga MA, Polackal MN, Ostriker AC, Chakraborty R, Wu CL, Sano S, Muralidharan S, Rius C, Vuong J, Jacob S, Muralidhar V, Robertson AA, Cooper MA, Andres V, Hirschi KK, Martin KA, and Walsh K. 2017. ‘Clonal hematopoiesis associated with TET2 deficiency accelerates atherosclerosis development in mice’, Science, 355: 842–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gage FH, and Temple S. 2013. ‘Neural stem cells: generating and regenerating the brain’, Neuron, 80: 588–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galderisi U, Helmbold H, Squillaro T, Alessio N, Komm N, Khadang B, Cipollaro M, Bohn W, and Giordano A. 2009. ‘In vitro senescence of rat mesenchymal stem cells is accompanied by downregulation of stemness-related and DNA damage repair genes’, Stem Cells Dev, 18: 1033–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Prat L, Martinez-Vicente M, Perdiguero E, Ortet L, Rodriguez-Ubreva J, Rebollo E, Ruiz-Bonilla V, Gutarra S, Ballestar E, Serrano AL, Sandri M, and Munoz-Canoves P. 2016. ‘Autophagy maintains stemness by preventing senescence’, Nature, 529: 37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge ZJ, Schatten H, Zhang CL, and Sun QY. 2015. ‘Oocyte ageing and epigenetics’, Reproduction, 149: R103–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gervais L, and Bardin AJ. 2017. ‘Tissue homeostasis and aging: new insight from the fly intestine’, Curr Opin Cell Biol, 48: 97–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giangreco A, Qin M, Pintar JE, and Watt FM. 2008. ‘Epidermal stem cells are retained in vivo throughout skin aging’, Aging Cell, 7: 250–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gierut JJ, Lyons J, Shah MS, Genetti C, Breault DT, and Haigis KM. 2015. ‘Oncogenic K-Ras promotes proliferation in quiescent intestinal stem cells’, Stem Cell Res, 15: 165–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladyshev VN 2013. ‘The origin of aging: imperfectness-driven non-random damage defines the aging process and control of lifespan’, Trends Genet, 29: 506–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnani D, Crippa S, Della Volpe L, Rossella V, Conti A, Lettera E, Rivis S, Ometti M, Fraschini G, Bernardo ME, and Di Micco R. 2019. ‘An early-senescence state in aged mesenchymal stromal cells contributes to hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell clonogenic impairment through the activation of a pro-inflammatory program’, Aging Cell: e12933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Goriely A, McVean GA, Rojmyr M, Ingemarsson B, and Wilkie AO. 2003. ‘Evidence for selective advantage of pathogenic FGFR2 mutations in the male germ line’, Science, 301: 643–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goriely A, McVean GA, van Pelt AM, O’Rourke AW, Wall SA, de Rooij DG, and Wilkie AO. 2005. ‘Gain-of-function amino acid substitutions drive positive selection of FGFR2 mutations in human spermatogonia’, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 102: 6051–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]