Abstract

The growth of lipidomics and the high isomeric complexity of the lipidome has revealed a need for analytical techniques capable of structurally characterizing lipids with a high degree of specificity. Lipids are morphologically diverse molecules that can exist as any one of a large number of isomeric species, and as such are often indistinguishable by mass spectrometry without a complementary separation method. Recent developments in the field of lipidomics aim to address these challenges by utilizing a combination of multiple analytical techniques which are selective to lipid primary structure. This review summarizes two emerging strategies for lipidomic analysis, namely, ion mobility-mass spectrometry and ion fragmentation via ozonolysis.

Keywords: Lipids, lipidomics, mass spectrometry, ion mobility-mass spectrometry, collision cross section, isomers, ozonolysis, molecular structure

1. Introduction

Lipids are an incredibly diverse class of molecules that regulate cellular activity, act as signaling molecules, and serve as the primary constituent of cell membranes, among other vital biological functions. As understanding of their complex roles in biological systems increases, lipids are gaining potential as therapeutic drug targets, especially given the intersection of lipid metabolic pathways with disease states such as cancer and diabetes [1–3]. The increasing relevance of lipids necessitates the development of analytical strategies for the discrimination and identification of these species in biological samples. Lipidomics, the broad scale analysis of the lipid content of a given system, poses unique analytical challenges due to the astounding structural diversity amongst lipids [3,4]. This issue is further complicated in that many lipid species are structural isomers, several examples of which are illustrated in Figure 1(a) for a common phosphatidylcholine species. Potentially hundreds of thousands of unique lipid molecules exist in biological samples, but only a small fraction of these have been putatively identified over recent decades. The source of this discrepancy is largely due to lipidomic workflows being generally developed for mass spectrometry (MS), a robust technology capable of identifying unknown species by mass [2–5]. Although MS allows for high-throughput analyses of complex samples, without a complementary separation method, MS measurements alone cannot distinguish isomeric components present in these samples. The necessity of the large degree of lipid isomerism produced in nature has yet to be determined; however, the specific, predictable lipid structural motifs have a distinctly biological basis. As an example, fatty acids (FAs) are used in the biosynthesis of six of the eight categories of lipids defined by the LipidMaps Consortium and therefore represent a useful model system for understanding broader lipid structural trends [6]. Biological synthesis of FAs is a widely conserved process across all eukaryotes and some prokaryotes, and although specific enzymes may differ between species, catalyzed condensation of acetyl-CoA units for chain elongation is generally involved [7,8]. For this reason, most endogenous FA molecules contain an even number of carbon atoms, and additional biological rules govern placement of double bonds via desaturation pathways. Attention to these biological guidelines provides researchers with a powerful tool to leverage in bioinformatics approaches for more sophisticated hypotheses for lipid analyses. As previously stated, one challenge in the field of lipidomics is the discrimination of isomeric species. The true number of naturally occurring isomeric lipid species is unknown, but it is estimated to be in the tens of thousands. The Human Metabolome Database (HMDB) released its most comprehensive update in 2018, along with a new category of metabolites termed “Expected” to represent species of known structures that have yet to be detected in the human body or for which the precise isomer has yet to be formally identified [9]. Over 90% of the 82,274 compounds reported in this category are lipids, indicating the potential scale of the isomer issue. A simple enumeration equation for FAs (Figure 1b) was developed by the authors to estimate the number of theoretical double bond positional isomers (DBPI) and cis/trans geometric isomers (GI) that can exist for unmodified (e.g., no hydroxylation, methylation, oxidation), straight chain fatty acids containing 18 carbon atoms, which are among the most abundant FA chain lengths encountered in nature. Established rules governing typical lipid structure were followed, which excludes double bonds positioned at the α- and ω-carbons and adjacent to additional double bonds. Calculation results for these equations are summarized in Table 1 and indicate that hundreds to tens of thousands of possible isomers exist for even the simplest FA lipids. A more rigorous enumeration of lipid isomers has been reported by Schuster et al. using generalized Fibonacci numbers, which in addition to DPBI and GI, considers the allowance of allenic and cumulenic FAs as well as modifications to the carbon chain. In their analysis, a C18 FA can have over 1×109 possible forms [10]. Although only a fraction of these theoretical FA isomer species are expected to occur biologically, it is currently unknown to what extent. Therefore, chemical separation and analysis approaches capable of differentiating various isomeric forms are necessary in order to improve current lipidomic strategies and expand the breadth of analytical information that can be obtained. Moreover, detailed knowledge of experimentally-observed lipid structural trends present in multidimensional analytical data will become critically important in guiding the development of predictive informatic tools and improve the confidence in lipid annotation and identification.

Fig. 1.

(a) Visualization of potential isomeric forms of PC 34:1 including sn-regioisomers, double bond positional isomers, geometric cis/trans isomers, and chiral stereoisomers. (b) Enumeration equations for the determination of double bond positional isomers and geometric isomers for simple, straight-chain fatty acids.

Table 1.

Theoretical number of double bond positional isomers and cis/trans isomers for unmodified, straight chain fatty acids containing 18 carbon atoms and 0-5 double bonds. Isomer numbers are calculated from the equations presented in Fig. 1b.

| Fatty Acid (FA) | Molecular Formula | Exact Mass (Da) ([M−H]−) | Number of Carbons | Number of Double Bonds | Number of Possible Double Bond Isomers | Number of Possible cis / trans Isomers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FA 18:0 | C18H36O | 283.2637 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| FA 18:1 | C18H34O | 281.2480 | 18 | 1 | 16 | 30 |

| FA 18:2 | C18H32O | 279.2324 | 18 | 2 | 105 | 392 |

| FA 18:3 | C18H30O | 277.2167 | 18 | 3 | 364 | 2756 |

| FA 18:4 | C18H28O | 275.2011 | 18 | 4 | 715 | 11000 |

| FA 18:5 | C18H26O | 273.1854 | 18 | 5 | 792 | 25104 |

2. New Directions in Lipidomic Analyses

Recent advances in mass spectrometry and related analytical techniques have helped drive the field of lipidomics forward. In particular, ion activation/fragmentation techniques such as collision-induced dissociation (CID) and electron impact excitation of ions from organics (EIEIO) have enabled the discrimination of sn-regioisomers [11–13]. Additionally, techniques which promote carbon-carbon double bond cleavage have been developed in conjunction with MS to identify double bond position, in particular the Paternò-Büchi (PB) and ozonolysis (Oz) reactions [14–16]. However, at this time there is no single technique capable of resolving all types of isomers commonly encountered in lipid samples (Figure 1(a)) [5,17]. Therefore, integration of multiple approaches is necessary to expand lipidome coverage and to differentiate isomeric species.

In this review, we focus predominantly on the utilization of ion mobility-mass spectrometry (IM-MS) for lipidomic analyses and its combination with orthogonal analytical techniques. IM is particularly suited to tackling the specific structural issues endemic to lipidomics discussed previously. The IM technique separates gas-phase ions based on differences in their collision cross section (CCS), a parameter that correlates to the two-dimensional cross sectional area of the molecule in the gas phase [18]. Prior studies indicate that the multidimensional separations resulting from IM-MS analyses are capable of differentiating isomers and delineating molecules into respective biomolecular classes [19,20]. When applied to lipids, IM-MS analyses have previously revealed specific and reproducible mobility-mass correlations related to differences in headgroup, acyl chain length, and degree of unsaturation [21]. The relationship between lipid structure and gas-phase conformation via IM-MS analysis are explored in the following section, with subsequent expansion towards predictive approaches and complementary analytical techniques.

3. Mobility-Mass Trends and Prediction of CCS for Lipid Analyses

One of the more interesting aspects of IM-MS data is the existence of empirical correlations between the analyte ion size (mobility) and its mass, i.e., chemical class trendlines which correspond to the specific conformation that the analyte ion adopts within the anhydrous, gas-phase environment of the IM spectrometer. These mobility-mass correlations are related to the primary structure of the analyte and thus are highly-specific for each biomolecular class [20,22–27]. For lipids, it has been shown that gas-phase packing is inefficient, resulting in a relatively large size-to-mass ratio that allows lipids to be readily differentiated from other molecules within a 2-dimensional IM-MS spectrum. Recent developments in commercial IM-MS instrumentation have allowed for larger numbers of lipids to be measured with high precision and reproducibility, which has facilitated the development of IM-MS lipidomic databases incorporating both size (CCS) and mass measurement information [28,29]. This in turn, has allowed for numerous sub-classes of lipids to be analyzed for specific size-mass trends which can be quantitatively-mapped in support of utilizing IM information for identifying and characterizing unknowns [28–31].

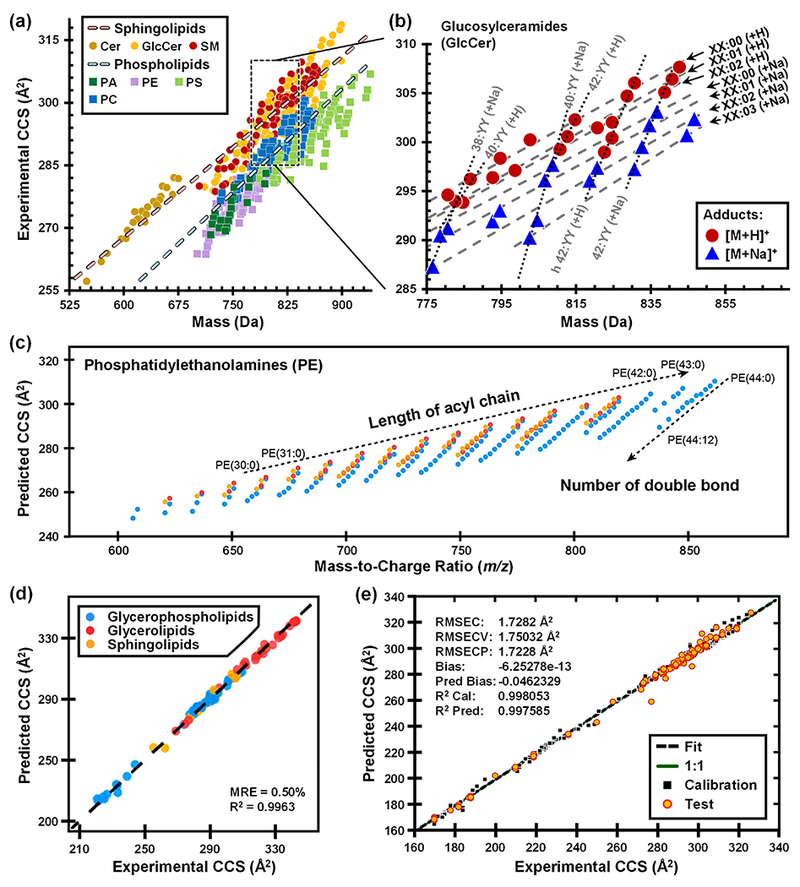

Recent work from the authors’ laboratory has focused on mapping IM-MS structural trends for broad classes of lipids (Figure 2a), yielding over 450 CCS measurements (DTCCSN2) for 217 unique lipid species obtained from four classes of glycerophospholipids (PC, PE, PS, PA) and three classes of sphingolipids (GlcCer, Cer, SM) [28]. This dataset was sufficiently large to allow specific structural trends to be quantitatively mapped for each lipid sub-class as well as for different ion forms (e.g., H+, Na+, H−, etc.) within each class, shown in Figure 2b for glucosylceramides. As with trends observed in smaller IM-MS studies using DTIMS [32–34] and TWIMS [35,36], the conformational orderings of lipids were found to be well-represented by linear functions [37] and reproducibly influenced by polar headgroup (lipid class), acyl chain length, degree of unsaturation, and ion form. Similar to previous findings [36], sphingolipids were found to adopt larger gas-phase conformations than phospholipids (quantitatively, by approximately 2-6% increase in CCS), with this observation being attributed to the limited degrees of unsaturation in sphingolipids due to the constraint imposed by the sn1 sphingosine backbone [28]. Linear equations were fitted to groups of lipids differing only in their number of double bonds or acyl chain carbon atoms, and it was found that variations in degree of unsaturation were three to four times as influential on the CCS as alkyl chain length for similar masses. The influence of the ion form on the CCS was found to be correlated to the size of the charge-carrier adduct, i.e., [M+2Na-H]+ > [M+K]+ > [M+Na]+ > [M+H]+ > [M−H]−.

Fig. 2.

(a) Experimentally measured DTCCSN2 vs mass measurements and linear regressions plotted for the two lipid categories, sphingolipids and phospholipids. (b) Quantitative correlations observed within GlcCer cation data corresponding to variation in either acyl chain length (i.e. XX:00) or degree of unsaturation (i.e. 42:YY). (c) Linear trends for three common PE lipid modifications (colored markers) to investigate the effect of acyl chain length and degree of unsaturation in [M+H]+ ions. (d) Intra-lab validation for correlation of predicted and experimental DTCCSN2 values for cations of three lipid classes. (e) Correlation of cross validation (CV)-predicted and experimental TWCCSN2 with root mean square error of calibration (RMSEC), cross validation (RMSECV), and test set prediction (RMSECP), as well as bias and fitness. Figure 2a adapted from K.L. Leaptrot, J.C. May, J.N. Dodds, J.A. McLean, Ion Mobility Conformational Lipid Atlas for High Confidence Lipidomics, Nat. Commun. 10 (2018) 1–9. Figures 2c, 2d adapted with permission from Z. Zhou, J. Tu, X. Xiong, X. Shen, Z.-J. Zhu, LipidCCS: Prediction of Collision Cross-Section Values for Lipids with High Precision To Support Ion Mobility–Mass Spectrometry-Based Lipidomics, Anal. Chem. 89 (2017) 9559–9566. Figure 2e adapted with permission from M.T. Soper-Hopper, A.S. Petrov, J.N. Howard, S.S. Yu, J.G. Forsythe, M.A. Grover, F.M. Fernández, Collision Cross Section Predictions Using 2-Dimensional Molecular Descriptors, Chem. Commun. 53 (2017) 7624-7627.

Zhu and coworkers have recently developed a machine learning model to predict lipid CCSN2 values [29]. Using a commercial DTIMS, the authors first empirically measured 458 lipid DTCCSN2 values across ten classes of glycerophospholipids (PC, PE, PG, PS, PI, PA, LPC, LPE, LPI, LPS), two classes of glycerolipids (TG, DG), and three classes of sphingolipids (SM, Cer, GlcCer). Linear trends for acyl chain length and degree of unsaturation were observed, such as is shown for PE lipids in Figure 2(c). Using this large pool of CCS data, the authors then developed a prediction model called LipidCCS Predictor, which was capable of predicting lipid CCS values with an externally validated median relative error of ca. 1% (Figure 2(d)). The support vector regression-based prediction models were built using optimized molecular descriptors (45 for cations and 66 for anions) to generate a large-scale, theoretical database of lipid CCS values, containing 63,434 predicted lipid CCS values covering 22 common lipid classes [29]. Both the LipidCCS Predictor and LipidCCS database are freely-accessible. For CCSN2 prediction, users can input SMILES structures into LipidCCS Predictor, which currently supports prediction for five commonly observed, singly charged adducts including [M+H]+, [M+Na]+, [M+NH4]−, [M+COOH]−, and [M−H]−.

Fernandez and coworkers recently demonstrated another machine-learning approach for predicting lipid CCS values using only 2-dimensional molecular descriptors (numerical representatives of chemical structure) as inputs [30]. From a database of TWCCSN2 measurements published by Astarita and coworkers [38], 195 values representing a wide variety of lipids were selected. An initial machine learning step prioritized 68 molecular descriptors of shape, symmetry, connectivity, chemical diversity, etc. upon which partial least squares (PLS) linear multivariate regression models were used to accurately predict CCS from 2D structures with a root mean square error for CCS prediction (RMSECP) of 1.72 Å2 (Figure 2(e)) [30]. These and other machine learning approaches to CCS prediction are critically important for populating large databases of lipid CCS values where experimental measurements cannot be obtained, such as the case for the near 100,000 lipids which are only theoretically predicted to exist [9].

While the numbers of high-quality, experimentally-measured lipid CCS values have increased drastically within the last few years, there are relatively few initiatives to integrate this data into lipidomic informatic workflows. Recently, McLean and coworkers compiled over 3,800 experimental DTCCSN2 values into an online, interactive resource called the Unified CCS Compendium. In addition to a large number of peptides, carbohydrates, and small molecule metabolites, this Compendium includes over 800 lipid CCS values, all of which have been scaled to reference values in order to make this resource self-consistent [31]. Regression models and predictive statistics were used in the Compendium to describe empirical size-mass correlations, and these mathematical relationships can serve as an identification filter in untargeted experimental workflows. As an example, the identification of an unknown biochemical species from a human serum sample was narrowed from 325 potential chemical formulas to 21 PC lipid isomers using the IM-MS information from the Compendium. This CCS filtering workflow results in higher confidence assignment of chemical class, and the predictive capabilities will support annotation of unknown chemical isomers which are commonly encountered in lipidomic and metabolomic studies. For lipid-specific analysis, Zhu and coworkers have recently developed a software tool known as LipidIMMS Analyzer to support the accurate identification of lipids using IM-MS [39]. The software incorporates a multi-dimensional database comprised of over 260,000 theoretical lipids annotated with predicted m/z, retention time, CCS, and fragmentation information and currently supports multiple data acquisition approaches and IM-MS instrumentation types. A test data set comprised of both lipid standards and biological samples yielded 500-600 lipid identifications through LipidIMMS Analyzer and indicated the increased identification confidence gained by utilizing a multidimensional approach [39]. While these and other IM-MS approaches provide important information for supporting identification of lipids from untargeted studies, comprehensive lipidomics requires more structural details than can yet be gleaned from trend and predictive analyses of CCS. Therefore, additional structurally-specific analytical techniques need to be employed, such as those addressed in the following section.

4. Diagnostic Double Bond Cleavage Coupled to IM-MS

Given the strong influence of molecular structure on biological function, the discrimination of lipid double bond positional isomers (Figure 1(a)) is an analytical challenge of great interest to the lipidomic community. Analyses combining MS and X-ray crystallography have shown that the position and degree of unsaturation of a lipid’s acyl chain(s) affect the ability of that species to fit in the binding pocket of an interacting protein partner [40,41]. Given the potential existence of thousands of double bond positional isomers in biological samples, the identification and separation of these species is a laborious yet crucial task. Therefore, it is beneficial to combine multiple stages of analytical techniques to enhance lipid isomer separation and identification [17].

While IM has been successfully applied to the separation of cis/trans lipid isomers, the differences in CCS of double bond positional isomers is generally too small to be resolved with current IM instrumentation [25,42]. Thus, to distinguish between double bond positional isomers, alternative strategies are necessary. While multiple analytical strategies have been developed for this purpose, including radical-derived processes such as ultraviolet photodissociation (UVPD) [43], electron impact excitation from organics (EIEIO) [13], and radical-directed dissociation (RDD) [44], here we will focus primarily on ion-molecule reactions that specifically target the C=C double bond.

Ozonolysis (Oz) [15,16,45–49] and Paternò-Büchi (PB) reactions [14,50–53] have both been utilized to target sites of unsaturation in lipids. A detailed comparison of these two reactions can be found in a recent review article, to which this work is complementary [5]. When interfaced with MS, Oz and/or PB reactions induce fragmentation at the C=C double bond, resulting in diagnostic fragment ions whose mass pinpoints the double bond location in the lipid precursor ion. The two approaches have been utilized in both shotgun [16,46,48,54] and HPLC-coupled workflows [55–58] and are capable of readily identifying a multitude of lipid C=C isomers in complex samples. In order to facilitate data analysis, custom software have been developed by both the Xia and Mitchell groups to automate the annotation of reaction products originating from Oz and PB reactions [57,59].

More recently, ozonolysis has been combined with IM-MS as an orthogonal dimension of separation [58,60–62]. Differential mobility spectrometry (DMS) as a front-end separation for ozonolysis has been used for structural characterization of unsaturated PCs, as well as 1-deoxysphingosine and its isomers [60–62]. Conversely, ozonolysis can also be performed prior to IM as part of an LC-Oz-IM-MS workflow (Figure 3(a)). In this case, IM separates the diagnostic ozonolysis fragment ions produced by the reaction, allowing further structural discrimination and improving sensitivity for low abundance fragments. For this workflow, the ozonolysis reaction can be performed either in solution or in the gas phase, with the latter implementation termed OzID [56,58]. The solution-phase method utilizes a low-pressure mercury lamp mounted parallel with the fluidics to convert dissolved oxygen gas into ozone that reacts with lipids before ionization in the ESI source. Alternatively, the gas phase approach requires modification of the IM-MS instrument such that ozone is introduced into the trapping ion funnel, allowing controlled reactions of ozone with lipid ions on timescales of 1-90 ms prior to injection into the IM drift tube. Because the rate of reaction is sufficiently fast, ozonolysis and OzID product ions can be correlated to precursors based on common retention times when LC separation is included.

Fig. 3.

(a) Example workflows combining IM and ozonolysis techniques. (b) A mixture of PC double bond positional isomers is converted to diagnostic products using LC-Oz-IM-MS. (c) IM elution order of cis/trans PE isomers is retained post-ozonolysis, allowing for identification of precursors. Figure 2b is adapted using data from R.A. Harris, J.C. May, C.A. Stinson, Y. Xia, J.A. McLean, Determining Double Bond Position in Lipids Using Online Ozonolysis Coupled to Liquid Chromatography and Ion Mobility-Mass Spectrometry, Anal. Chem. 90 (2018) 1915–1924. Figure 3c is adapted with permission from B.L.J. Poad, X. Zheng, T.W. Mitchell, R.D. Smith, E.S. Baker, S.J. Blanksby, Online Ozonolysis Combined with Ion Mobility-Mass Spectrometry Provides a New Platform for Lipid Isomer Analyses, Anal. Chem. 90 (2018) 1292–1300. Copyright 2018 American Chemical Society.

An example of how ozonolysis can be used to elucidate double bond location is depicted in Figure 3(b), where the IM-MS spectrum of a mixture of PC 18:1(9Z)/18:1(9Z) and PC 18:1(6Z)/18:1(6Z) double bond positional isomers is shown. The primary spectral peaks at m/z 786.6 and m/z 808.6 represent the [M+H]+ and [M+Na]+ cations, respectively. The isomer with double bonds at the 9Z positions reacted with ozone to form products at m/z 676.5 [M+H]+ and m/z 698.4 [M+Na]+, while the isomer with double bonds at the 6Z positions gave products at m/z 634.4 [M+H]+ and m/z 656.4 [M+Na]+. Each of these species possesses a unique drift time, which corresponds to the time taken for that particular ion to traverse through the drift tube. This drift time is proportional to the size and shape of the molecule in the gas phase, and it has previously been observed that changing the position and orientation of a lipid species’ double bond changes the molecule’s resulting drift time [25].

Blanksby and coworkers have demonstrated that differences in unique drift times for cis/trans isomer precursors allows for correlation to and identification of their product ions in combined OzID-IM experiments [56]. When running a mixture of PE cis/trans isomers, namely PE 18:1(9Z)/18:1(9Z) and PE 18:1(9E)/18:1(9E), it was observed that the cis isomer exhibited a lower drift time than the trans isomer (Figure 3(c)). This relationship was retained post-OzID in the fragment ions, and although the two resulting products had the same mass, they could be identified based upon their IM elution order.

Ion mobility separations and ozonolysis reactions exist as orthogonal techniques, and when combined serve as a powerful analytical tool for lipid isomer discrimination and identification. The work described here illustrates that combined LC-Oz/OzID-IM-MS workflows allow for the differentiation of both cis/trans isomers and double bond positional isomers, two of the four isomer types described in Figure 1(a). The ongoing work to integrate these techniques into a standard LC-MS lipidomics workflow will rely on the development of bioinformatics software for the automated assignment of spectral peaks that, once completed, will enable thousands of lipid identifications from a single experiment, bringing the field closer to the capability of cataloguing the entirety of the lipidome.

5. Conclusions

Lipidomics as a field has experienced enormous growth in past decades, but still faces critical challenges due to the structural complexity of lipid species and the high degree of isomerism hindering putative identifications. New analytical developments leverage the highly-conserved rules of lipid biosynthesis on expected lipid structure to more fully characterize lipid samples. In particular, IM-MS analysis of lipids reveals quantitative structural trends based on headgroup, acyl chain length, and degree of unsaturation. Combining IM with targeted ion-molecule reactions such as Oz and PB provide orthogonal dimensions of separation for further discrimination of isomeric species. Future directions to further interrogate lipid structural trends include bioinformatics approaches, such as predicting CCS, and the integration of IM and novel ion activation techniques into existing lipidomic workflows, both of which will promote improved identifications and expansion of the current lipidomic landscape.

Highlights:

Discusses the biological basis for lipid structure and using empirical structural patterns to guide predictive tools

Reviews lipid mobility-mass trends in light of headgroup, acyl chain length, and degree of unsaturation

Explores new directions in lipidomic analyses including CCS predictions and double-bond targeted reactions

Emphasizes combination of multiple analytical approaches for full lipidome coverage

Acknowledgements

RH acknowledges the Harold Stirling Graduate Fellowship from the Vanderbilt University Graduate School. This work was supported in part using the resources of the Center for Innovative Technology (CIT) at Vanderbilt University. Financial support for aspects of this research was provided by the National Institutes of Health (NIH NIGMS R01GM092218 and NIH NCI R03CA222452) and the U.S. Army Research Office and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) under Cooperative Agreement no. W911 NF-14-2-0022. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the Army Research Office, DARPA, or the U.S. Government.

Abbreviations

- HMDB

The Human Metabolome Database

- MS

Mass spectrometry

- LC

Liquid chromatography

- LC-MS

Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry

- HPLC

High pressure liquid chromatography

- ESI

Electrospray ionization

- CID

Collision-induced dissociation

- EIEIO

Electron impact excitation of ions from organics

- PB

Paternò-Büchi

- Oz

Ozonolysis

- OzID

Ozone-induced dissociation

- UVPD

Ultraviolet photodissociation

- RDD

Radical-directed dissociation

- IM

Ion mobility spectrometry

- IM-MS

Ion mobility-mass spectrometry

- CCS

Collision cross section

- DTCCSN2

Drift tube CCS measured in nitrogen drift gas

- TWIMS

Traveling wave ion mobility spectrometry

- DMS

Differential mobility spectrometry

- FA

Fatty acid

- PA

Phosphatidic acid

- PE

Phosphatidylethanolamine

- PC

Phosphatidylcholine

- PS

Phosphatidylserine

- GlcCer

Glucosylceramide

- Cer

Ceramide

- SM

Sphingomyelin

- PI

Phosphatidylinositol

- PG

Phosphatidylglycerol

- LPC

Lyso-phosphatidylcholine

- LPE

Lyso-phosphatidylethanolamine

- LPI

Lyso-phosphatidylinositol

- LPS

Lyso-phosphatidylserine

- TG

Triacylglycerides

- DG

Diacylglycerides

- GP

Glycerophospholipids

- SP

Sphingolipids

- GL

Glycerolipids

- GI

Geometric isomers

- DBPI

Double bond positional isomers

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Evans JF, Hutchinson JH, Seeing the future of bioactive lipid drug targets, Nat. Chem. Biol 6 (2010) 476–479. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Rolim AEH, Henrique-Arúdjo R, Ferraz EG, Dultra F.K. de Araújo Alves, Fernandez LG, Lipidomics in the study of lipid metabolism: Current perspectives in the omic sciences, Gene. 554 (2015) 131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2014.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Wenk MR, The emerging field of lipidomics, Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 4 (2005) 594–610. doi: 10.1038/nrd1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Navas-Iglesias N, Carrasco-Pancorbo A, Cuadros-Rodríguez L, From lipids analysis towards lipidomics, a new challenge for the analytical chemistry of the 21st century. Part II: Analytical lipidomics, TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 28 (2009) 393–403. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2008.12.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Zheng X, Smith RD, Baker ES, Recent advances in lipid separations and structural elucidation using mass spectrometry combined with ion mobility spectrometry, ion-molecule reactions and fragmentation approaches, Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 42 (2018) 111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2017.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Fahy E, Subramaniam S, Brown HA, Glass CK, Merrill AH, Murphy RC, Raetz CRH, Russell DW, Seyama Y, Shaw W, Shimizu T, Spener F, van Meer G, VanNieuwenhze MS, White SH, Witztum JL, Dennis EA, A comprehensive classification system for lipids., J. Lipid Res 46 (2005) 839–861. doi: 10.1194/jlr.E400004-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Smith S, Witkowski A, Joshi AK, Structural and functional organization of the animal fatty acid synthase, Prog. Lipid Res 42 (2003) 289–317. doi: 10.1016/S0163-7827(02)00067-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].White SW, Zheng J, Zhang Y-M, Rock CO, the Structural Biology of Type Ii Fatty Acid Biosynthesis, Annu. Rev. Biochem 74 (2005) 791–831. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Wishart DS, Feunang YD, Marcu A, Guo AC, Liang K, Rosa V, Sajed T, Johnson D, Li C, Karu N, Sayeeda Z, Lo E, Assempour N, Berjanskii M, Singhal S, Arndt D, Liang Y, Badran H, Grant J, Serra-cayuela A, Liu Y, Mandal R, Neveu V, Pon A, Knox C, Wilson M, Manach C, Scalbert A, Human T, Database M, HMDB 4.0 : the human metabolome database for 2018, 46 (2018) 608–617. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Schuster S, Fichtner M, Sasso S, Use of Fibonacci numbers in lipidomics – Enumerating various classes of fatty acids, Nat. Publ. Gr (2017) 1–9. doi: 10.1038/srep39821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Blanksby SJ, Mitchell TW, Advances in Mass Spectrometry for Lipidomics, Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem 3 (2010) 433–465. doi: 10.1146/annurev.anchem.111808.073705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Murphy RC, Axelsen PH, Mass spectrometric analysis of long-chain lipids, Mass Spectrom. Rev 30 (2011) 579–599. doi: 10.1002/mas.20284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Campbell JL, Baba T, Near-complete structural characterization of phosphatidylcholines using electron impact excitation of ions from organics, Anal. Chem 87 (2015) 5837–5845. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b01460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Ma X, Xia Y, Pinpointing double bonds in lipids by paternò-büchi reactions and mass spectrometry, Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed 53 (2014) 2592–2596. doi: 10.1002/anie.201310699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Thomas MC, Mitchell TW, Harman DG, Deeley JM, Murphy RC, Blanksby SJ, Elucidation of Double Bond Position in Unsaturated Lipids by Ozone Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry, Anal. Chem 79 (2007) 5013–5022. doi: 10.1021/ac0702185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Thomas MC, Mitchell TW, Harman DG, Deeley JM, Nealon JR, Blanksby SJ, Ozone-Induced Dissociation: Elucidation of Double Bond Position within Mass-Selected Lipid Ions, Anal. Chem 80 (2008) 303–311. doi: 10.1021/ac7017684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Hancock SE, Poad BLJ, Batarseh A, Abbott SK, Mitchell TW, Advances and unresolved challenges in the structural characterization of isomeric lipids, Anal. Biochem 524 (2017) 45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2016.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Mason EA, McDaniel EW, Transport Properties of Ions in Gases, Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co; KGaA, Weinheim, FRG, 1988. doi: 10.1002/3527602852. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Fenn LS, Kliman M, Mahsut A, Zhao SR, McLean JA, Characterizing ion mobility-mass spectrometry conformation space for the analysis of complex biological samples, Anal. Bioanal. Chem 394 (2009) 235–244. doi: 10.1007/s00216-009-2666-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].May JC, Goodwin CR, Lareau NM, Leaptrot KL, Morris CB, Kurulugama RT, Mordehai A, Klein C, Barry W, Darland E, Overney G, Imatani K, Stafford GC, Fjeldsted JC, McLean JA, Conformational ordering of biomolecules in the gas phase: Nitrogen collision cross sections measured on a prototype high resolution drift tube ion mobility-mass spectrometer, Anal. Chem 86 (2014) 2107–2116. doi: 10.1021/ac4038448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Kliman M, May JC, McLean JA, Lipid analysis and lipidomics by structurally selective ion mobility-mass spectrometry, Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 1811 (2011) 935–945. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2011.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Tao L, McLean JR, McLean JA, Russell DH, A collision cross-section database of singly-charged peptide ions, J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 18 (2007) 1232–1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Fenn LS, McLean JA, Biomolecular structural separations by ion mobility-mass spectrometry, Anal. Bioanal. Chem 391 (2008) 905–909. doi: 10.1007/s00216-008-1951-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].McLean JA, The Mass-Mobility Correlation Redux: The Conformational Landscape of Anhydrous Biomolecules, J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 20 (2009) 1775–1781. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Kyle JE, Zhang X, Weitz KK, Monroe ME, Ibrahim YM, Moore RJ, Cha J, Sun X, Lovelace ES, Wagoner J, Polyak SJ, Metz TO, Dey SK, Smith RD, Burnum-Johnson KE, Baker ES, Uncovering biologically significant lipid isomers with liquid chromatography, ion mobility spectrometry and mass spectrometry, Analyst. 141 (2016) 1649–1659. doi: 10.1039/C5AN02062J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].May JC, McLean JA, The Conformational Landscape of Biomolecules in Ion Mobility-Mass Spectrometry, in: Wilkins CL, Trimpin S (Eds.), Ion Mobil. Spectrom. Spectrom. Theory Appl., 1st ed, CRC press, 2010: pp. 326–342. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Woods AS, Ugarov M, Egan T, Koomen J, Gillig KJ, Fuhrer K, Gonin M, Schultz JA, Lipid/peptide/nucleotide separation with MALDI-ion mobility-TOF MS, Anal. Chem 76 (2004) 2187–2195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Leaptrot KL, May JC, Dodds JN, McLean JA, Ion Mobility Conformational Lipid Atlas for High Confidence Lipidomics, Nat. Commun 10 (2019) 1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-08897-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Zhou Z, Tu J, Xiong X, Shen X, Zhu Z-J, LipidCCS: Prediction of Collision Cross-Section Values for Lipids with High Precision To Support Ion Mobility-Mass Spectrometry-Based Lipidomics, Anal. Chem 89 (2017) 9559–9566. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b02625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Soper-Hopper MT, Petrov AS, Howard JN, Yu SS, Forsythe JG, Grover MA, Fernández FM, Collision cross section predictions using 2-dimensional molecular descriptors, Chem. Commun 53 (2017) 7624–7627. doi: 10.1039/C7CC04257D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Picache JA, Rose BS, Balinski A, Leaptrot KL, Sherrod SD, May JC, McLean JA, Collision cross section compendium to annotate and predict multi-omic compound identities, Chem. Sci 10 (2019) 983–993. doi: 10.1039/C8SC04396E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Jackson SN, Ugarov M, Post JD, Egan T, Langlais D, Schultz JA, Woods AS, A study of phospholipids by ion mobility TOFMS, J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 19 (2008) 1655–1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Trimpin S, Tan B, Bohrer BC, O’Dell DK, Merenbloom SI, Pazos MX, Clemmer DE, Walker JM, Profiling of phospholipids and related lipid structures using multidimensional ion mobility spectrometry-mass spectrometry, Int. J. Mass Spectrom 287 (2009) 58–69. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Jackson SN, Barbacci D, Egan T, Lewis EK, Schultz JA, Woods AS, MALDI-ion mobility mass spectrometry of lipids in negative ion mode, Anal. Methods 6 (2014) 5001–5007. doi: 10.1039/c4ay00320a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Kim HI, Kim H, Pang ES, Ryu EK, Beegle LW, Loo JA, Goddard WA, Kanik I, Structural Characterization of Unsaturated Phosphatidylcholines Using Traveling Wave Ion Mobility Spectrometry, Anal. Chem 81 (2009) 8289–8297. doi: 10.1021/ac900672a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Paglia G, Angel P, Williams JP, Richardson K, Olivos HJ, Thompson JW, Menikarachchi L, Lai S, Walsh C, Moseley A, Plumb RS, Grant DF, Palsson BO, Langridge J, Geromanos S, Astarita G, Ion mobility-derived collision cross section as an additional measure for lipid fingerprinting and identification, Anal. Chem 87 (2015) 1137–1144. doi: 10.1021/ac503715v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Zhang F, Guo S, Zhang M, Zhang Z, Guo Y, Characterizing ion mobility and collision cross section of fatty acids using electrospray ion mobility mass spectrometry, J. Mass Spectrom 50 (2015) 906–913. doi: 10.1002/jms.3600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Paglia G, Williams JP, Menikarachchi L, Thompson JW, Tyldesley-Worster R, Halldórsson S, Rolfsson O, Moseley A, Grant D, Langridge J, Palsson BO, Astarita G, Ion mobility derived collision cross sections to support metabolomics applications, Anal. Chem 86 (2014) 3985–3993. doi: 10.1021/ac500405x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Zhou Z, Shen X, Zhu Z-J, Tu J, Chen X, Xiong X, LipidIMMS Analyzer: integrating multi-dimensional information to support lipid identification in ion mobility—mass spectrometry based lipidomics, Bioinformatics. 35 (2018) 698–700. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Shinzawa-Itoh K, Aoyama H, Muramoto K, Terada H, Kurauchi T, Tadehara Y, Yamasaki A, Sugimura T, Kurono S, Tsujimoto K, Mizushima T, Yamashita E, Tsukihara T, Yoshikawa S, Structures and physiological roles of 13 integral lipids of bovine heart cytochrome c oxidase, EMBO J. 26 (2007) 1713–1725. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Brown SHJ, Mitchell TW, Oakley AJ, Pham HT, Blanksby SJ, Time to face the fats: What can mass spectrometry reveal about the structure of lipids and their interactions with proteins?, J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 23 (2012) 1441–1449. doi: 10.1007/s13361-012-0410-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Groessl M, Graf S, Knochenmuss R, High resolution ion mobility-mass spectrometry for separation and identification of isomeric lipids., Analyst. 140 (2015) 6904–6911. doi: 10.1039/c5an00838g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Klein DR, Brodbelt JS, Structural Characterization of Phosphatidylcholines Using 193 nm Ultraviolet Photodissociation Mass Spectrometry, Anal. Chem 89 (2017) 1516–1522. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b03353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Pham HT, Ly T, Trevitt AJ, Mitchell TW, Blanksby SJ, Differentiation of complex lipid isomers by radical-directed dissociation mass spectrometry, Anal. Chem 84 (2012) 7525–7532. doi: 10.1021/ac301652a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Sun C, Zhao YY, Curtis JM, A study of the ozonolysis of model lipids by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry, Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom 26 (2012) 921–930. doi: 10.1002/rcm.6183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Pham HT, Maccarone AT, Thomas MC, Campbell JL, Mitchell TW, Blanksby SJ, Structural characterization of glycerophospholipids by combinations of ozone- and collision-induced dissociation mass spectrometry: The next step towards “top-down” lipidomics, Analyst. 139 (2014) 204–214. doi: 10.1039/c3an01712e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Vu N, Brown J, Giles K, Zhang Q, Ozone-induced dissociation on a traveling wave high-resolution mass spectrometer for determination of double-bond position in lipids, Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom 31 (2017) 1415–1423. doi: 10.1002/rcm.7920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Barrientos RC, Vu N, Zhang Q, Structural Analysis of Unsaturated Glycosphingolipids Using Shotgun Ozone-Induced Dissociation Mass Spectrometry, J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 28 (2017) 2330–2343. doi: 10.1007/s13361-017-1772-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Stinson CA, Zhang W, Xia Y, UV Lamp as a Facile Ozone Source for Structural Analysis of Unsaturated Lipids Via Electrospray Ionization-Mass Spectrometry, J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2 (2017). doi: 10.1007/s13361-017-1861-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Ma X, Chong L, Tian R, Shi R, Hu TY, Ouyang Z, Xia Y, Identification and quantitation of lipid C=C location isomers: A shotgun lipidomics approach enabled by photochemical reaction, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 113 (2016) 2573–2578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1523356113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Stinson CA, Xia Y, Method of coupling Paternò-Büchi reaction with direct infusion ESI-MS/MS for locating C=C bond in glycerophospholipids, Analyst. 141 (2016) 3696–3704. doi: 10.1039/C6AN00015K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Ma X, Zhao X, Li J, Zhang W, Cheng JX, Ouyang Z, Xia Y, Photochemical Tagging for Quantitation of Unsaturated Fatty Acids by Mass Spectrometry, Anal. Chem 88 (2016) 8931–8935. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b02834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Murphy RC, Okuno T, Johnson CA, Barkley RM, Determination of Double Bond Positions in Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids Using the Photochemical Paternò-Büuchi Reaction with Acetone and Tandem Mass Spectrometry, Anal. Chem 89 (2017) 8545–8553. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b02375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Ren J, Franklin ET, Xia Y, Uncovering Structural Diversity of Unsaturated Fatty Acyls in Cholesteryl Esters via Photochemical Reaction and Tandem Mass Spectrometry, (2017) 1432–1441. doi: 10.1007/s13361-017-1639-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Kozlowski RL, Campbell JL, Mitchell TW, Blanksby SJ, Combining liquid chromatography with ozone-induced dissociation for the separation and identification of phosphatidylcholine double bond isomers, Anal. Bioanal. Chem 407 (2015) 5053–5064. doi: 10.1007/s00216-014-8430-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Poad BLJ, Zheng X, Mitchell TW, Smith RD, Baker ES, Blanksby SJ, Online Ozonolysis Combined with Ion Mobility-Mass Spectrometry Provides a New Platform for Lipid Isomer Analyses, Anal. Chem 90 (2018) 1292–1300. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b04091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Batarseh AM, Abbott SK, Duchoslav E, Alqarni A, Blanksby SJ, Mitchell TW, Discrimination of isobaric and isomeric lipids in complex mixtures by combining ultra-high pressure liquid chromatography with collision and ozone-induced dissociation, Int. J. Mass Spectrom 431 (2018) 27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ijms.2018.05.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Harris RA, May JC, Stinson CA, Xia Y, McLean JA, Determining Double Bond Position in Lipids Using Online Ozonolysis Coupled to Liquid Chromatography and Ion Mobility-Mass Spectrometry, Anal. Chem 90 (2018) 1915–1924. doi : 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b04007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Zhang W, Zhang D, Chen Q, Wu J, Ouyang Z, Xia Y, Online photochemical derivatization enables comprehensive mass spectrometric analysis of unsaturated phospholipid isomers, Nat. Commun 10 (2019) 1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07963-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Maccarone AT, Duldig J, Mitchell TW, Blanksby SJ, Duchoslav E, Campbell JL, Characterization of acyl chain position in unsaturated phosphatidylcholines using differential mobility-mass spectrometry., J. Lipid Res 55 (2014) 1668–77. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M046995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Steiner R, Saied EM, Othman A, Arenz C, Maccarone AT, Poad BLJ, Blanksby SJ, von Eckardstein A, Hornemann T, Elucidating the chemical structure of native 1-deoxysphingosine, J. Lipid Res 57 (2016) 1194–1203. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M067033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Poad BLJ, MacCarone AT, Yu H, Mitchell TW, Saied EM, Arenz C, Hornemann T, Bull JN, Bieske EJ, Blanksby SJ, Differential-Mobility Spectrometry of 1-Deoxysphingosine Isomers: New Insights into the Gas Phase Structures of Ionized Lipids, Anal. Chem 90 (2018) 5343–5351. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b00469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]