Abstract

In the USA, Black girls and women face significant health disparities and disproportionately experience violence, racism, discrimination, stereotype messaging and elevated STI/HIV rates. Research shows the importance of familial systems and effective communication in decreasing risky behaviours among Black girls. This grounded theory study explored sociocultural conditions that influence the process of becoming a sexual Black woman. Analytic results of interviews with 20 Black women identified protection as a major category associated with Black female sexual development and related risk behaviour. This paper describes the role of Black women as protectors of young Black female sexuality, the sociocultural protective strategies they used across the life course, and the consequences of absent protection. Findings can inform future evidence-based, culturally sensitive interventions to promote the sexual health and development of Black girls and women in the USA.

Keywords: Black women, girls, HIV prevention, reproductive health, sexual behaviour, USA

Introduction

In the USA, Black girls face overwhelming health disparities as they disproportionately experience violence, racism, discrimination, stereotype messaging and elevated STI/HIV risk (Crooks et al. 2019; Brown, White-Johnson and Griffin-Fennell 2013; Green 2017). Black girls endure various types of violence in their homes, schools and neighbourhoods (Green 2017). Sexual violence is common; 20% of Black women are raped during their lifetime (Green 2017). Black girls also experience institutionalised racism, particularly in government schools. They are often viewed as “disruptive”, “loud” or “defiant” by school administrators and are more likely to be suspended or expelled at higher rates than other girls due to dress code violations, which could simply be attributed to their body shape (Green 2017). The media often portray Black girls and women as sexualised beings (Crooks et al. 2019; Stokes 2007; Coleman et al. 2016). This type of stereotype messaging can indirectly contribute to elevated STI/HIV risk because Black girls often emulate the provocative dress and behaviour they observe in social media (Crooks et al. 2019; Brown, White-Johnson and Griffin-Fennell 2013; Rosenthal and Lobel 2016; Townsend et al. 2010). Black girls are more likely to have sexual contact by age 13 (Ward and Benjamin 2004) and nearly half (48%) aged 14–19 years acquire an STI (Forhan et al. 2008). Although the relationship between sexual stereotype messaging and increased sexual risk behaviour in Black girls has been well established (Brown, White-Johnson and Griffin-Fennell 2013; Townsend et al. 2010; West 2008), Black women may be positioned to help, but little is known about how they protect young Black female sexuality (Brown, White-Johnson and Griffin-Fennell 2013; Schooler et al. 2004; Townsend et al. 2010).

A major task of parenting is teaching children how to interpret societal messages and to help them determine their place in society (Greene 1990; Townsend 2008). This difficult task is made even more challenging for Black women in the face of racism and sexism, making them a “double minority” (Collins 1990; Greene 1990). Greene (1990) suggests that racism and sexism are transmitted through parenting interactions, values and messaging to their children. The “sociohistorical reality” of Black women being treated as sexual objects can be traced back to slavery in the Americas (Stephens and Phillips 2005). Collins (2004) explains how current media images of Black women come from an earlier era of racial oppression and popular images of Black culture shaped by race, gender and class. Messages from the dominant society that depict Black girls and women as sexual objects limit their choices about the roles deemed acceptable for them. Such derogatory images obscure the true strength and resilience of Black women (Greene 1990; Crooks et al. 2019). Previous research about female sexual development has predominantly been based on White women; whereas, sexual scripts, theories and models of Black women development are non-existent (Stephens and Phillips 2005; Stokes 2007). Ward and Benjamin (2004) argue that contemporary research on girl’s development focused on “White middle-class girlhood,” fails to incorporate cultural variation, and neglect the intersectionality of multiple identities, such as gender, race and economic status.

Effective communication between parents and adolescents is essential for the transmission of intergenerational values, attitudes and knowledge (Aronowitz, Rennells and Todd 2005; Stephens and Phillips 2005; Teitelman, Ratcliffe and Cederbaum 2008). Aronowitz, Rennells and Todd (2005) found that Black daughters’ perceptions of their mothers’ values related to social behaviours created an environment in which the daughters felt more confident in discussing sensitive issues and were more likely to have fewer risk behaviours. Black mothers can influence early adolescent behaviour as they are often their daughters’ primary sources for sex education (Aronowitz and Eche 2013; DiIorio et al. 2007). However, the particular strategies that Black mothers use to protect their daughters’ sexual development are unclear. Aronowitz and Eche (2013) examined parenting style and strategies of Black mothers and their findings revealed that they used a variety of psychological and behavioural strategies to control behaviour, but it was not clear if these strategies were effective at reducing sexual risk behaviours. Furthermore, the authors did not explicitly consider the wider sociocultural context of Black mother-daughter relationships.

For many girls and women, relationships with their mothers can influence how they view themselves and how they may socialise their own daughters (Greene 1990). Greene (1990) suggests that it is the responsibility of Black mothers to reject societal messages (i.e. White standards of beauty) and prevent disparaging messages about Black girls and women from being passed to their daughters and future generations. However, socialising Black girls in a society that devalues and sexualises Black women becomes particularly difficult for Black mothers when they themselves are uncomfortable talking about sex. Black women historically have been socialised to remain silent about sexuality or sexual behaviour (Fordham 1993; Hammonds 1999). Crooks et al. (2019) found a “culture of silence” exists within Black communities on topics about sexual health, which also speaks to the invisibility of Black women in discourses of sexuality (Weekes 2003). Collins (2004) suggests that many Black families retain traditional values that date back to the 17th Century, such as sex may only occur with the confines of marriage, sex is for procreation, children should be protected from sexual information, and abstinence is the preferred method of birth control. Such beliefs would clearly suppress intergenerational communication about sex and sexuality. Additional research is urgently needed with contemporary perspectives about the sexual development of Black girls and how Black women protect themselves and younger girls. The purpose of this paper is to describe the role of Black women as protectors, the sociocultural strategies they employ to protect and the consequences of protection or its absence.

Methods

Study design

A grounded theory study was conducted between May 2016 and January 2017 to explore the sociocultural conditions influencing the process of becoming a sexual Black woman (Crooks et al. 2019). The major goal of this study was to develop a conceptual model describing Black female sexual development. Grounded theory is informed by symbolic interactionism, which focuses on social interaction between individuals undergoing a shared experience and uncovering the actions, conditions and consequences that follow (Blumer 1986). Approval for the study was obtained from the University of Wisconsin-Madison Institutional Review Board (IRB). This focuses on findings regarding the concept of protection in relation to Black girls’ sexuality.

Recruitment

The study involved a purposive sample of twenty young Black women recruited using flyers and word of mouth, from university and community settings (e.g., community centres, beauty supply stores, and sexual health clinics) in an urban midwestern city. In line with grounded theory, theoretical sampling was used to expand the sample to gain conceptual clarity and further densify categories and dimensions that evolved from the data (Strauss and Corbin 1990). Initial inclusion criteria for the study required participants to be Black women ages 18–24 year with the history of an STI. As the influence of older Black women became apparent, the researchers expanded the sample to include Black women older than 24 years to reflect sexual development across the life course. Additionally, women without a history of STIs were included to offer researchers a broader perspective about Black female sexuality. The final inclusion criteria for the study consisted on: (a) self-identify as a Black woman, (b) 18 years and older, and (c) fluent in speaking and reading the English language. Sampling continued until saturation was reached, the point at which no new properties, dimensions or conditions can be identified (Strauss and Corbin 1990). The IRB approved all changes in inclusion criteria.

Data collection and analysis

In accordance with grounded theory, data collection and analysis occurred simultaneously. Constant comparative analysis was used to identify categories of social processes within and between participants, dimensions within categories, and conditions that influenced actions participants took in relation to their sexuality (Charmaz 2014; Strauss and Corbin 1990). The first author, who is a content expert, interviewed participants and analysed data with the assistance of two grounded theory experts. Individual in-depth interviews were conducted in a private space of the participant’s choice, lasting 28 to 95 minutes. Participants were compensated $30 for their participation. All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim for analysis.

Data were analysed using open, axial and selective coding. Initial data were collected using open-ended questions, e.g., “Can you tell me about things in your life that contributed to your STI risk or diagnosis?” Open coding using line by line analysis was completed to generate early codes and categories (Charmaz 2014). Axial coding was used to make connections between the categories and specify dimensions of the categories (Glaser and Strauss 2009). Later questions became more focused to densify categories and to identify related conditions. For example, to more fully understand the concept of protection questions shifted to: what has your experience been with Black women protecting your sexuality; what does protection mean to you; how do Black women protect younger Black girls; and what happens when the protection is not there? Finally, selective coding was used to clarify relationships among categories and develop a comprehensive conceptual model (Strauss and Corbin 1990).

Multiple procedures were used to ensure rigour within the study. Data analysis was conducted with a research team to recognise and minimise bias (Sandelowski 1986). Member checking was used to assure credibility of results, in which the researcher brought portions of the analysis back to participants during interviews for their feedback about categories, dimensions, and connections among categories (Charmaz 2014). All categories and dimensions included in the conceptual model developed as the result of the study were supported by quotes. Pseudonyms were used in reporting quotes to protect participants anonymity and confidentiality. Researchers also searched for cases in which the data did not support particular findings

Results

Sample

Sixteen women were recruited from community and four from university settings. All participants were sexually active, fifteen reported having had an STI and six reported recurrent STIs. Ages ranged from 19–62 years and the mean age was 31. Fifteen participants identified as Black, two as Black Latinas and three as biracial. The majority of participants were single, two were married and two were divorced. Seven participants identified as mothers with an average number of children of three. The majority of participants were heterosexual, two reported engaging in same sex as well as heterosexual intimacy, and one identified as bisexual. The average age of sexual initiation (i.e. sexual intercourse) was 11 years old. Forty-five percent of the sample had an annual income category of US $0–10,000. Two participants had completed 8th grade, nine had a high school Diploma or General Education Development (GED), two had technical degrees, four had bachelors’ degree and three had doctorates.

The Model

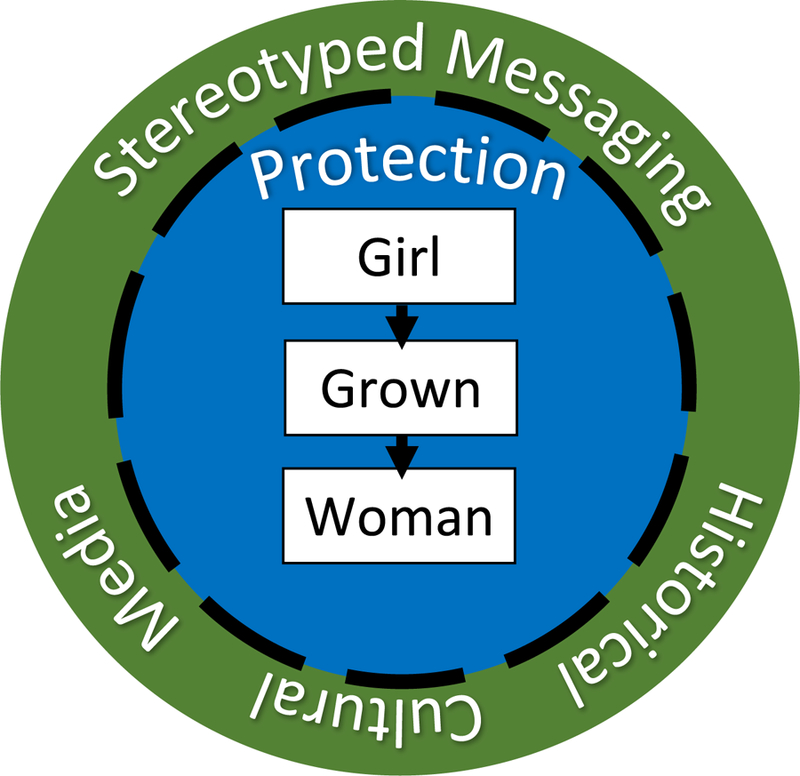

Findings resulted in the development of a conceptual model explaining the process of becoming a sexual Black woman (Figure 1). Participants identified three sequential phases of sexual development: Girl, Grown and Woman. The Girl phase was characterised as an early time, often between 5 and 14 years old, in their lives when participants lacked knowledge about sex, had little control of their own sexuality and needed protection. During the Grown phase, typically occurring between ages 11 and 18, participants tried to figure out their sexual identities and they developed strategies to protect themselves. The Woman phase, often began around 18 or when participants became parents, they described embracing their sexuality; and many became protectors of the sexual development of younger girls (Crooks et al. 2019). Stereotyped messaging and the need for protection were major sociocultural conditions associated with their sexual development. Stereotype messaging was defined as visual images, words, or stories in the media, culture and history that sexualised Black female bodies (Crooks et al. 2019). Participants identified the concept of protection as a key condition in their sexual development and this therefore merited a separate analysis and report.

Figure 1.

Becoming a Sexual Black Woman

Protection

Protection was described as a means to prevent the early sexualisation of Black girls and delay their progression into the next phase of their sexual development until they were more mature (Crooks et al. 2019). Participants described protection as means to support the sexual development and emergence of Black girls’ sexuality through developing safe spaces, sharing personal stories and increasing knowledge about sexual health topics. As girls, participants identified wanting protection from older Black women, which could be anyone that cared for the girl such as mothers, grandmothers, or other Black women in the community.

Black Women as Protectors

Our findings revealed that many Black women become protectors of their own and others’ children (especially girls), their communities, themselves and images of Black women. Participants described being valued for their bodies and seen as sexual objects by larger society as noted by Latoya, age 19: “As a Black woman you are constantly seen as this promiscuous sexual creature, not necessarily seen as the person that you are you are just seen as this body… I guess nobody really looks at you…they don’t see you as a person.” Participants worked to redefine the sexualised images of Black women to one that embodies strength and empowerment. They wanted others to recognise them and other Black women for their non-sexual roles, (e.g. as providers, mothers and women) and value them for their personhood:

“Our history is unique as Black women…I feel like, we’re amazing, honestly. Like, we go through a lot and somehow… we push through. It’s, to be strong. Like no matter the circumstance and to be your version of strong. It might not look strong to someone else, or whatever, but it’s strong for you…its perseverance, endurance, we endure a lot, we put up with a lot and we overcome” (Maya, 19).

Black women described wanting to protect Black girls so that they would not have to encounter the mistakes or “hardships” they had endured. Hardships included sexual assault, abuse, partner’s infidelity and/or contracting an STI. They explained that older Black women needed to physically protect Black girls because Black men and the law failed to do so.

Participants described going through pubescence at earlier chronological ages compared to their White peers. Consequently, their physical maturity exceeded their psychological preparedness for matters related to sex: thus, making them easy targets for sexual predators (Crooks et al. 2019). This situation was compounded by the culture of silence in Black communities that prevented informative conversations about sex and sexuality. Therefore, Black women often initiated protective strategies when they became mothers, had close friends who needed protection, or witnessed threats to Black female sexuality. In the absence of institutional mechanisms of protection (e.g. law enforcement or schools) for Black girls, older Black women described taking this role of protectors. In fact, they noted that many forces, such as the law, oppressive systems (i.e. prisons), racism and stereotyped messages, actually worked against their efforts. When asked why Black women protect, participants responded:

“Protecting someone else keeps them safe. But it also keeps you safe. Another way of looking at protecting, it keeps you on this earth. So, our legacy, our lineage will continue to go forth” (Sheila, 57).

“[We protect] because we love ourselves, we love our bodies. We don’t want nothing to happen with our bodies or our daughters’ bodies” (Jennifer, 42).

Participants described how men are typically considered the family protectors and providers. However, participants also talked about historical conditions (such as the forced separation of families, slavery, unemployment, mass incarceration, racial profiling) have prevented many Black men from fulfilling that role. Thus, Black women, by default, have become the “protectors” for their families and communities.

“That definitely goes back to slavery. We’ve always protected others…I mean it was the order of operations back then and being the cornerstones of our families. And Black women have always been told to hold it down and fight for it and it’s internalised in us” (Sasha, 27).

Physical environmental strategies

Many older participants described protective strategies that involved controlling the physical environments of their children, particularly their daughters. They did so by keeping their children close to their homes, making sure they were home by a certain time, knowing who their children associated with, and prohibiting sleepovers or time spent in others’ homes. To protect Black girls from sexually explicit messaging, older women monitored the television programmes that girls watched or the music they listened to, as described by Mariah, 26:

“I was very limited on the things I could watch and the things I could hear. My mom stole my Brittany Spears CD…. she wouldn’t let me listen to non-Christian music in the house. Or like movies I couldn’t watch a lot of movies my friends were allowed to watch. Some of those subliminal messages I didn’t receive…there was a strong message from my mom that we weren’t doing those things in her house.”

Participants also described protecting Black girls from the “outside world” meaning those beyond their home community. Older Black women taught children about appropriate physical touch and healthy boundaries as well as what to do if anyone attempted to sexually abuse them. Participants involved children in extracurricular activities, such as church, sports or afterschool programs, to keep them safe from the outside world and predators. Additionally, participants taught their children to be aware of their surroundings, notice treats to their safety, and if necessary, physically fight to protect themselves. Tonya, 52, described this:

“I (protect them) from predators. My daughters and them know all the ins and outs. And if they find someone following them, they always have pay attention to their surroundings… If you had to protect yourself, this is a whole other person trying to get at you… I said when you swing you swing hard. You swing straight for the head.”

Verbal informational strategies

Older Black women used information as a tool to protect Black girls. Mothers tried to maintain open communication with their daughters regarding sex. To help their daughters avoid the threatening situations, mothers disclosed information about their own sexual experiences as girls. Black women also encouraged girls to get to know their potential partners over time before having sex and taught them how to initiate conversations about safe sex. They taught girls to be aware of predators or messages from society that threatened their sexuality. Participants described entering puberty as early as 8 or 9 years old, therefore they encouraged younger Black girls to protect their bodies by wearing clothing that de-emphasised their sexual development:

“Don’t talk to them (predators), wear decent clothes… Keep them away from, you know, around these older men, make sure they have on decent clothes…because their body is performing like grown folks… I mean, they bodies just out there…protect yourself” (Jennifer, 42).

Cultural strategies

Older Black women described using culturally specific messages to discourage behaviour that place girls at risk for sexual exploitation. One example was labelling girls as “fast.” Older participants used this label to “call out the girl’s behaviour” if they were acting or dressing promiscuous (Crooks et al. 2019). Jennifer, age 42, explained the protective intent: “Yes, they are saying it (fast) to protect us. Because they already know how life is out here in the world, because they’ve been through it.” Older women explained that they wanted to convey messages to Black girls to “slow down” and savour their youth and innocence. Sheila, 57, said:

“Fast means…you trying to do things that your body is not ready for, that your mind is not ready for, that you are not ready for. You moving too quick… you’re making decisions too hastily. For instance, if you twelve and somebody say you a fast little girl, that means that you over here trying to be eighteen. If you sixteen, you over here trying to be twenty-five.”

Although older Black women used fast as a protective strategy it was not always understood as such by young girls. When reflecting on this term, many participants reported feeling confused by the meaning of the fast label:

“The elders tell you moving so fast, but they never told us, well what’s fast?” (Sheila, 57).

“I think it goes back to who’s in the household because, if you’re being taught don’t be fast, don’t do this, and no one is really explaining to you what being fast is, so it’s like, okay, grandma, mom, how am I being fast, what am I doing that I’m fast? Give me the terminology so I know” (Anika, 34).

Consequently, some participants thought the label defined them and acted accordingly by engaging in sexualised behaviour:

“You can always tell someone not to be something, but eventually they’re going to want to figure out why you don’t want them to be this way, like what’s wrong with being fast? Why can’t I be fast? I think I ended up rebelling because I’m like, well the fast girls have more fun, you know… I felt like I was missing out” (Brandy, 23).

Religious messaging

Many older Black women used religious messages as a form of spiritual protection. Participants reported having their children attend church as a way to instil moral values and norms about sex (i.e. suppressing sexual urges or not talking about sex). Mariah, 26, shared; “We had a religious household I think from a young age it was like don’t have sex...until you are married or at least older.” Although many Black women protected others, they did not feel as though they, themselves, were protected by most of society. Thus, some relied only on God for protection, while others also relied on other Black women:

“I’m always trying to protect somebody, but who protects me? God, He the only one who protects me” (Sharon, 62).

“No one protects the Black women aside from god or other Black women” (Tonya, 52).

Some participants described how religious messages often evoking feelings of shame, silence or fear in Black girls. Religious beliefs, suggesting that sex was bad or sinful and should not be discussed, made participants uncomfortable when communicating about sex or their sexual desires. Consequently, they felt ashamed of their sexuality and mature physical development, which further silenced Black girls and women. This was particularly true for participants who experienced traumatic events or were peer pressured into having sex. Maya, 19, described how Black women in her family used religion as way of shaming her into not having sex:

“I was kind of religious growing up and like, everything surrounded my sexuality always felt that like it was like a sin, it was horrible, and it was bad, but it was also confusing…. because I started to like really feel ashamed of these natural things.”

Erica, 20, described how religion and context of the south associated sex with being dirty or immoral:

“I think there’s a lot of shame already towards women this whole idea of women being the ones to make men dirty or to make their partners umm… dirty or unclean especially being from the south there is a feeling that I’ve gotten that sex means being dirty or unclean or that theme being very present umm…especially like when it comes to spirituality or religion like Christianity being like very prevalent, like Baptist.”

Rejecting stereotyped messages

Rejecting stereotyped messages of sexualisation represented a major protection strategy used by Black women. Strategies for rejecting the message included doing research and gaining information about sexuality and associating themselves with peers who were or trying to combat stereotypes. Rejecting such messages was described as “fighting”, not listening to or ignoring the stereotypes. In so doing, women felt empowered to talk about sex and decide for themselves when and with whom to have or not have sex. They also expressed an increased sense of self-worth, and an image of self as being more than just a sexual being. Katrina, 23, shared her story of rejecting these messages:

“When I was in high school…I just hated always being that sex object…always being looked at in that way… I didn’t date at all in high school because, I felt like I was too good for people and I’m kind of glad I did you know, because it, it instilled in me that I’m not a sex object … there’s more to me than my body.”

Participants who rejected stereotyped messages also described strategies to overcome the culture of silence about sex in Black communities. They sought information about sexual health from online resources or their health care providers. When participants rejected stereotyped messages, they often waited until they were older before becoming sexually active because they believed that they were more than sexual objects. Participants described rejecting stereotyped messaging as an ever-present and ongoing process:

“(I am) constantly reminding myself that I’m not a stereotype, I’m my own person” (Maya, 19).

“But the work [to rejecting stereotype messages] is daily. And what I mean by that, you have to work at it daily” (Sheila, 57).

Older Black women described instilling values of self-worth, self-esteem and confidence in their daughters as another way to combat stereotyped messages. This intergenerational strategy was shared by Felicia, 40: “my parents taught me values that I, I try to instil in my own kids and make them strong.” Participants provided girls with counter-messages of Black women that reflect strength, empowerment and encouraged them to embrace their Black identity. Older Black women helped girls recognise how stereotyped messages threatened their sexual development. A Mariah, 26, explains how her mother’s messages had a positive impact on her sense of self:

“Confidence or self-value, or self-awareness I think that that definitely comes from the protective layer, but I think it’s is such a big apart of your sexuality and how you present yourself, how you see yourself and how you let others come into your life…. I feel like this has been the key distinction for me. The choices I have made have led me for the most part to be more cautious with sex.”

Impact of Presence or Absence of Protection

Participants described some of the positive effects of protection. Participants who had protectors often rejected stereotype messages because older Black women limited exposure to such messaging or offered them alternative positive representations of Black females. Protectors instilled values of self-respect and self-worth. Thus, participants who reported having protectors expressed a sense of empowerment, greater control of their bodies and sexuality. An example of this is provided in the following quote:

“I had a two-parent household…they taught me values…they instilled the image of a Black woman as strong and empowered” (Anika, 34).

Although participants stated that culturally and historically Black women typically assumed the role of protector, some participants explained that not all Black women become protectors. Some women were not always capable of protecting themselves. They had not learned how to protect because they were not protected as children or were not able to do so because of power dynamics in relationships. Protection was not always afforded to participants as they described Black girls and women not always capable of protecting themselves or others. This disruption in or lack of protection is represented as a dotted line in Figure 1. Many participants described intergenerational cycles of lack of protection that made them more vulnerable to sexual exploitation:

“I think that all women aspire to be that (protector). But I think if a woman was never been protected, she wouldn’t know how to exemplify that… if you don’t protect, you’re perpetuating the cycle” (India, 26).

“I think it’s possible that women do not become protectors. Especially when you are talking about sexual abuse or childhood sexual molestation…Let’s say you are looking at a family, not only has the child been sexually molested, her mother has been molested and her grandmother was. So, it might not be purposeful that they don’t want to be protectors, but their conception of protecting or their ability to protect or the desire to protect may not manifest itself in a way that actually protects” (Ada, 26).

“I don’t think every woman does (protect). So, there is definitely like this circle or cycle, like my aunt. I love her with my whole heart. Like she had a bunch of kids when she was young, and her kids are having kids young. She definitely is not protecting her children in the way that she should” (Latoya, 19).

The intergenerational cycle of unprotected youth was repeatedly mentioned as having an adverse impact on the sexual development of Black women, specifically during the transition from Girl to Grown. Some spoke about how their relationship with their mothers or other Black women had influenced their sexual decisions in terms of partner choices or exploring sexual experiences. The degree of protection influenced whether participants rejected or accepted the stereotyped messages as described by a Latoya, 19:

“Lacking protection is like the lack of knowledge or the lack of parents... Because that is how these stereotype messages will get in and affect the girl, but if they have protection there is a wall blocking the message…Black girls especially really do need protection because of older men trying to get at them and if you don’t have anyone to protect you. You don’t know what to do. It’s yeah. It’s very scary. And the development of their body and just societal views. Like little Black girls aren’t considered little girls, they are considered young adults from the get.”

Accepting Stereotyped Messages

Given the overwhelming prevalence of these stereotyped messages many participants, as girls, internalised these messages, came to view themselves as sexual beings, and emulated the provocative and promiscuous behaviour of images portrayed in the media. During the Girl phase, participants described emulating the stereotypes they were presented with. As Katrina, 23, put it: “in terms of growing up, that’s (media) a big thing. You know, like monkey see, monkey do. The consequences for those who accepted the stereotype messages were entering the Grown phase at a younger chronological age than those who rejected them. Examples of accepting the stereotyped message included dressing promiscuously, engaging in sex at an early age, having sex with multiple partners and not caring what others thought of their behaviour. Brandy, 23, described accepting the stereotype message:

“Once you hit a certain point, like you know, you can be like, okay I’m fast…I mean you accept it …you learn to accept your actions more…I’m having sex too young and…this is the girl that my mom tried to warn me not to become. But it’s hard not to become that when you’re always getting told what not to be and not what you should be… So, if somebody tell me I’m being fast I’m like, well that’s my actions.”

Discussion

Findings from this study significantly extend research on Black female sexuality by describing specific protective strategies that Black women use to support the sexual development of young Black girls. The importance of protection to the physical and psychological wellbeing of young Black girls cannot be overstated. The salience of protection may be most profoundly recognised when it is absent, as evidenced by Black women’s testimonies about their experiences of childhood sexual abuse and adult sexual exploitation or molestation.

This need for protection of Black girls and women is not a new phenomenon. Black women have a history of oppression that has required them to nurture resilience and adaptive capacities (Bell and Nkomo 1998; Greene 1990). Greene (1990) identified “racial socialization” as a process that African American parents, especially mothers, do to socialise their children cognitively and emotionally about what it means to be Black in the USA, what to expect, how to cope and how to reject stereotyped messages from society. Bell and Nkomo referred to this racial socialisation process, specific to Black women, as “armoring”, which is a “form of socialization whereby a girl child acquires the cultural attitudes, preferences and socially legitimate behaviours for two cultural contexts…is also a political strategy for self-protection…whereby a girl develops…resistance to defy racism and sexism” (Bell and Nkomo 1998: 286). The results of our study build on the previous empirical literature by explaining the social and cultural conditions that contribute to the presence and absence of protection, the consequences of protection or lack thereof, and social strategies that contemporary Black women employ to protect the next generation of Black girls.

Protection may be considered a controversial intervention because of the historical devaluation of Black people, especially Black women within the larger US society. Greene states, “the image of childhood as protected development period during which children mature and explore the world unencumbered by many of life’s stark and dangerous realties’ does not hold true for the majority of Black children” (1990, 216). This statement speaks to what we discovered about Black girls not being viewed as minors due to their physical maturity, which increased their risk of sexual assault, early engagement in sexual activity and ultimately STI/HIV risk. Similar to our findings, Greene (1990) found that parents did not feel adequately prepared by their own parents to educate their daughters about sex or how to avoid sexual predators. Thus, the intergenerational cycles of unprotected youth continue. We found that a culture of silence in Black spaces/communities perpetuates this problem, a finding that aligns with the sexual silence described by (Konkle-Parker et al. 2018). These authors explained that this lack of communication about sex within Black families led to a lack of protection for women at both a societal and individual level. Our findings highlight the importance of protecting Black girls, the challenges Black women face when protecting and the need for Black communities to communicate about Black girls’ sexual experiences. It is critical that society recognises that Black girls are worthy of protection. The historical and present-day dangers of stereotype messages combined with lack of protection and communication pose serious threats to their sexual health. Therefore, it is essential that researchers and health care providers incorporate Black girls’ voices into discussions about sexual development and how best to intervene in ways that effectively protect and optimise their physical and psychological development.

Additionally, our findings suggest that Black women use several strategies to protect and help girls reject stereotyped messages that are prominent in social spaces. Although the popular media has been a major source of damaging stereotyped messages, it can also become a valuable source of accurate information about sexual health. Stephens and Phillips (2005) found that the media was the most influential source of sexual information for adolescents. Wingood et al. (2001) found that Black girls who watch sexually explicit videos that features Black actors were two times likely to have multiple sexual partners, more frequent sex and were not as likely to use contraception. Participants in our study validated that Black girls and women receive strong sexualised stereotype messages through various forms of media. Similarly, Greene (1990) found that Black adolescents are overpowered by the message that society places little value on their existence and emphasises their bodies. Greene’s research (1990) also suggests that Black girls may grow up under cultural conditions that contradict the values of dominant culture. Noble (2000) echoed these sentiments, noting many historical associations between Blackness and sexuality that silence and shame the expression of Black female sexuality. Weekes (2003) argues that it is very difficult for Black women to create sexual spaces outside of these stereotypes. Similarly, our findings showed that Black women worked to intentionally reject dominant societal stereotyped messaging about Black females as sexual objects.

Unlike Greene’s (1990) findings that other family members’ influence might be less intense or powerful than a “natural mother”, our findings suggest that other women in the community who were considered trustworthy, caring and credible sources of information about sex and sexual relationships could serve as protectors for Black girls. Similar to Aronowitz and Eche (2013), we identified monitoring, limit setting and instilling values as strategies that Black mothers used to decrease sexual behaviours in their daughters. Future research should focus on interventions that utilise and/or adapt the protective strategies of Black women to prevent the early sexualisation of Black girls. Our findings highlight the strength and resilience that Black women embody and should be emphasised in the development of STI/HIV prevention programs.

Many sexual health researchers conceptualise “protection” as prevention in the form of a physical barrier such as a condom, getting vaccines or getting tested for STI/HIV (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2016). Our findings suggest that the concept of protection is broader and may include other forms of physical safeguards as well as psychological, cultural, and religious strategies. Results point to the need for more effective family or parental programming regarding the protection of Black girls’ sexual development.

Limitations

Our sample consisted only of Black women; therefore, the findings are limited to this population. The sample was also restricted to participants over the age of 18 years who reflected back on their experiences when they were younger. Other conditions that influence Black female sexual development and protection based on perspectives of girls that are currently in the Girl phase may exist. Furthermore, the protection of sexuality was only discussed within a heterosexual context as our sample identified. Geographical location too may be a limitation as participants were recruited from the Midwest USA and social norms may differ by geographical context.

Conclusion

Findings from this study provide direction for future programmes and interventions that focus on the protection of Black female sexuality and sexual development. Additional research is needed to investigate how Black girls under the age of 18 years view the concept of protection, who they view as protectors and how they are protected. This line of inquiry is essential to optimising the physical and psychological sexual development of Black girls and women. Researchers need to further examine the effectiveness of the protective strategies identified in this study, in fostering positive self-images and preventing threats to Black female sexual health.

References

- Aronowitz Teri, and Eche Ijeoma. 2013. “Parenting Strategies African American Mothers Employ to Decrease Sexual Risk Behaviors in Their Early Adolescent Daughters.” Public Health Nursing 30 (4): 279–287. doi: 10.1111/phn.12027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronowitz Teri, Rennells Rachel E., and Todd Erin. 2005. “Heterosocial Behaviors in Early Adolescent African American Girls: The Role of Mother-Daughter Relationships.” Journal of Family Nursing 11 (2): 122–139. doi: 10.1177/1074840705275466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell Ella LJ Edmondson, and Nkomo Stella M.. 1998. “Armoring: Learning to Withstand Racial Oppression.” Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 285–295. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41603565 [Google Scholar]

- Blumer Herbert. 1986. Symbolic Interactionism: Perspective and Method Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown Danice L., White-Johnson Rhonda L., and Griffin-Fennell Felicia D.. 2013. “Breaking the Chains: Examining the Endorsement of Modern Jezebel Images and Racial-Ethnic Esteem among African American Women.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 15 (5): 525–539. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2013.772240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2016. “Sexually Transmitted Diseases Surveillance 2015” Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats15/std-surveillance-2015-print.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz Kathy. 2014. Constructing Grounded Theory London: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman M. Nicole, Butler Ebony O., Long Amanda M., and Fisher Felicia D.. 2016. “In and out of Love with Hip-Hop: Saliency of Sexual Scripts for Young Adult African American Women in Hip-Hop and Black-Oriented Television.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 18 (10): 1165–1179. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2016.1175029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins Patricia Hill. 1990. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Collins Patricia Hill. 2004. Black Sexual Politics: African Americans, Gender, and the New Racism New York: Routledge. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crooks Barbara King, Tluczek Audrey, and McDermott Sales Jessica. 2019. “The Process of Becoming a Sexual Black Woman: A Grounded Theory Study.” Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health 51 (1): 17–25. doi: 10.1363/psrh.12085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiIorio Colleen, Frances McCarty Pamela Denzmore, and Landis Andrea. 2007. “The Moderating Influence of Mother-Adolescent Discussion on Early and Middle African-American Adolescent Sexual Behavior.” Research in Nursing & Health 30 (2): 193–202. doi: 10.1002/nur.20193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fordham Signithia. 1993. “‘Those Loud Black Girls’:(Black) Women, Silence, and Gender ‘Passing’ in the Academy.” Anthropology & Education Quarterly 24 (1): 3–32. doi: . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Forhan Sara E., Gottlieb Sami L., Sternberg Maya R., Xu Fujie, Deblina Datta S, Berman Stuart, and Markowitz Lauri E.. 2008. “Prevalence of Sexually Transmitted Infections and Bacterial Vaginosis among Female Adolescents in the United States: Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2003–2004.” In National STD Prevention Conference, 10–13. https://cdc.confex.com/cdc/std2008/techprogram/P14888.HTM [Google Scholar]

- Glaser Barney G., and Strauss Anselm L.. 2009. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research New York: Transaction Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Green. 2017. “Violence Against Black Women – Many Types, Far-Reaching Effects.” Institute for Women’s Policy Research, July https://iwpr.org/violence-black-women-many-types-far-reaching-effects/ [Google Scholar]

- Greene Beverly A. 1990. “What Has Gone before: The Legacy of Racism and Sexism in the Lives of Black Mothers and Daughters.” Women & Therapy 9 (1–2): 207–230. 10.1300/J015v09n01_12. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hammonds Evelynn M. 1999. “Toward a Genealogy of Black Female Sexuality: The Problematic of Silence.” In Feminist Theory and the Body: A Reader, 93–104. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Konkle-Parker Deborah, Fouquier Katherine, Portz Kaitlin, Wheeless Linnie, Arnold Trisha, Harris Courtney, and Turan Janet. 2018. “Women’s Decision-Making about Self-Protection during Sexual Activity in the Deep South of the USA: A Grounded Theory Study.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 20 (1): 84–98. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2017.1331468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble Denise. 2000. “Ragga Music: Dis/Respecting Black Women and Dis/Reputable Sexualities.” Un/Settled Multiculturalisms: Diasporas, Entanglements, Transruptions, 148–169. https://drbirdonthewing.files.wordpress.com/2017/10/ragga-music-disreputable-sexualities.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal Lisa, and Lobel Marci. 2016. “Stereotypes of Black American Women Related to Sexuality and Motherhood.” Psychology of Women Quarterly 40 (3): 414–427. doi: 10.1177/0361684315627459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski Margarete. 1986. “The Problem of Rigor in Qualitative Research.” Advances in Nursing Science 8 (3): 27–37. doi: 10.1097/00012272-198604000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schooler Deborah, Monique Ward L, Merriwether Ann, and Caruthers Allison. 2004. “Who’s That Girl: Television’s Role in the Body Image Development of Young White and Black Women.” Psychology of Women Quarterly 28 (1): 38–47. 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2004.00121.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens Dionne P., and Phillips Layli. 2005. “Integrating Black Feminist Thought into Conceptual Frameworks of African American Adolescent Women’s Sexual Scripting Processes.” Sexualities, Evolution & Gender 7 (1): 37–55. 10.1080/14616660500112725. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stokes Carla E. 2007. “Representin’in Cyberspace: Sexual Scripts, Self-Definition, and Hip Hop Culture in Black American Adolescent Girls’ Home Pages.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 9 (2): 169–184. doi: 10.1080/13691050601017512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, and Corbin. 1990. Basics of Qualitative Research Vol. 15 Sage Newbury Park, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Teitelman Anne M., Ratcliffe Sarah J., and Cederbaum Julie A.. 2008. “Parent—Adolescent Communication about Sexual Pressure, Maternal Norms about Relationship Power, and STI/HIV Protective Behaviors of Minority Urban Girls.” Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association 14 (1): 50–60. doi: 10.1177/1078390307311770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend Tiffany G. 2008. “Protecting Our Daughters: Intersection of Race, Class and Gender in African American Mothers’ Socialization of Their Daughters’ Heterosexuality.” Sex Roles 59 (5–6): 429 10.1007/s11199-008-9409-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend Tiffany G., Thomas Anita Jones, Neilands Torsten B., and Jackson Tiffany R.. 2010. “I’m No Jezebel; I Am Young, Gifted, and Black: Identity, Sexuality, and Black Girls.” Psychology of Women Quarterly 34 (3): 273–285. 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2010.01574.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ward Janie Victoria, and Benjamin Beth Cooper. 2004. “Women, Girls, and the Unfinished Work of Connection: A Critical Review of American Girls’ Studies.” In All about the Girl: Culture, Power, and Identity, edited by Harris A, 15–28. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Weekes Debbie. 2003. “Keeping It in the Community: Creating Safe Spaces for Black Girlhood.” Community, Work & Family 6 (1): 47–61. 10.1080/1366880032000063897. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- West Carolyn M.. “Mammy, Jezebel, Sapphire and Their Homegirls: Developing an” Oppositional Gaze” toward the Images of Black Women.”. 2008 https://works.bepress.com/DrCarolynWest/15/ [Google Scholar]

- Wingood Gina M., DiClemente Ralph J., Harrington Kathy, Davies Suzy, Hook Edward W., and Kim Oh M. 2001. “Exposure to X-Rated Movies and Adolescents’ Sexual and Contraceptive-Related Attitudes and Behaviors.” Pediatrics 107 (5): 1116–1119. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.5.1116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]