Abstract

The 2016 U.S. presidential election coincided with the rise of the “alternative right” or “alt-right”. Alt-right associates have wielded considerable influence on the current administration and on social discourse, but the movement’s loose organizational structure has led to disparate portrayals of its members’ psychology and made it difficult to decipher its aims and reach. To systematically explore the alt-right’s psychology, we recruited two U.S. samples: An exploratory sample through MTurk (N = 827, Nalt-right = 447), and a larger nationally representative sample through the National Opinion Research Center’s Amerispeak panel (N = 1283, Nalt-right = 71 – 160, depending on the definition). We estimate that 6% of the U.S. population and 10% of Trump voters identify as alt-right. Alt-right adherents reported a psychological profile more reflective of the desire for group-based dominance than economic anxiety. Although both the alt-right and non-alt-right Trump voters differed substantially from non-alt-right non-Trump-voters, the alt-right and Trump voters were quite similar, differing mainly in the alt-right’s especially high enthusiasm for Trump, suspicion of mainstream media, trust in alternative media, and desire for collective action on behalf of Whites. We argue for renewed consideration of overt forms of bias in contemporary intergroup research.

Keywords: political psychology, extremism, intergroup relations, alt-right

The 2016 U.S. presidential election broke with orthodoxy on numerous counts. One of its most surprising features was the election of Donald Trump despite his flouting both conservative orthodoxy and U.S. political norms forbidding offensive speech targeting minorities.

Trump’s election coincided with the rise of a political movement, the “alternative right” or “alt-right”, that took an active role in cheerleading his candidacy and several of his controversial policy positions (Bryden & Silverman, 2019; Schreckinger, 2017). Although both academics (Hawley, 2017; Nagle, 2017; Zannettou et al., 2018) and the popular press (Caldwell, 2016; NPR staff, 2016; Schreckinger, 2017) have written much about the movement and its role in the 2016 election, there is much less direct empirical examination of its membership’s psychological profile and goals. Some of the opaqueness of the alt-right follows from the movement’s largely decentralized structure: in contrast to other far-right organizations or parties previously studied (e.g., the AfD in Germany; Lega Nord in Italy; the Danish People’s Party; UKIP in the U.K.) whatever formal organization the alt-right has exists primarily online (Bokhari & Yiannopoulos, 2016; Caldwell, 2016; Lyons, 2017; NPR staff, 2016), and the group lacks an official platform or clear membership criteria.

Still, the movement has wielded influence over politics and social discourse. At various points during Trump’s administration, individuals publicly associated with the alt-right, such as Stephen Bannon, had considerable influence on it (Schreckinger, 2017), dramatically increasing the movement’s reach and political power. Moreover, alt-right associates have shown a willingness to use aggressive behavior in pursuing their aims, including doxxing of political opponents (i.e., publicly releasing sensitive personal information on the internet; (Broderick, 2017) and violence at political rallies (Berkeleyside staff, 2017), most notably a deadly attack during the “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia (Heim, 2017). Beyond the theoretical significance of the alt-right’s rise, the movement’s emergent political influence and the willingness of some of its adherents to use extreme tactics to achieve their objectives highlight the practical need to better understand the psychological roots of alt-right support. Here, we provide the first systematic quantitative examination of the alt-right’s psychology, using a nationally representative random probability sample to provide insight into alt-right adherent’s demographics, traits, values, and goals.

Current accounts emphasize different elements of alt-right psychology. On one end of the spectrum are portrayals characterizing the movement as primarily driven by an antiestablishment and anti-globalist sentiment (Bokhari & Yiannopoulos, 2016; Daniszewski, 2016; Guardian style editors, 2016). On the other end are portrayals characterizing the movement as driven by anxiety about threats to the status and power of US-born Whites (Caldwell, 2016; Daniszewski, 2016; Gest, Reny, & Mayer, 2017; Lyons, 2017; Southern Poverty Law Center, n.d.), with some outlets explicitly labeling the movement as White supremacist (Armstrong, 2017; NPR staff, 2016). These differing views of the alt-right make distinct predictions about its primary goals. If alt-right support primarily reflects the type of anti-establishment sentiment often ascribed to populist parties, one would expect its adherents to focus on transferring power from perceived elites to perceived non-elites — that is, taking power from “the (corrupt) establishment” and giving it to “the (pure) people” (Mudde & Kaltwasser, 2012; see also Bakker, Rooduijn, & Schumacher, 2016; Skocpol & Williamson, 2016). If the alt-right support primarily reflects the desire for group-based dominance, one would expect its adherents to focus on protecting and promoting the political interests of Whites and other favored groups. These characterizations need not be mutually exclusive: A given person may identify with the movement because of both anti-establishmentarianism and supremacism, perhaps especially if they view Whites as a victimized group whose plight the elites have ignored (Bai & Federico, 2019; Craig & Richeson, 2014; Mutz, 2018; Norton & Sommers, 2011)1. We consider all these possibilities in this examination.

Just as spirited as the debate about the psychology of alt-right support is a related set of questions about its prevalence (Hawley, 2018) — both in U.S. society generally and among Trump supporters in particular. Assuming that White identity concerns are at the core of alt-right ideologies, some politicians and activists have expressed alarm at the possibility that the psychology of alt-right adherents finds widespread currency among Trump’s base of support (Mauricia, 2017). And indeed, several scholars have suggested that factors at the core of the supremacist portrayal of the alt-right — such as racial resentment (Schaffner, Macwilliams, & Nteta, 2018), white identification (Jardina, 2019; Sides, Tesler, & Vavreck, 2017), and status anxiety (Mutz, 2018) — were important drivers of support for Trump. Others bristle at these suggestions, considering them little more than a political smear to dismiss and distract from legitimate issues such as border control, declining job prospects, and corruption in Washington (Alexander, 2018). Still others wonder how the alt-right’s roots compare to those of other politically insurgent groups like the Antifa movement, a self-proclaimed anti-fascist movement that arose to oppose the alt-right in Charlottesville and elsewhere. Some commentators portray the Antifa just as much a threat as the alt-right, claiming “These goons and thugs oppose free speech, celebrate violence, despise dissent, and have little use for anything else in the American political tradition” (Goldberg, 2017).

We directly address these questions here. Specifically, we estimate the proportion of Americans who support the alt-right and compare their psychological profile to that of (a) non-alt-right people who voted for Trump and (b) non-alt-right people who did not vote for Trump. The variables we assessed as part of evaluating people’s psychological profile covered a broad swathe of outcomes that could be considered reflective of “anti-establishmentarianism” and “group-based supremacism”. We define “anti-establishmentarianism” as suspicion of elites and mainstream institutions (see also Mudde, 2004) and “supremacism” as a belief that some groups are superior to others and need their interests protected (Arena & Arrigo, 2000; see also Ho et al., 2015). For anti-establishmentarianism, our variables included concern about the gap between elites and non-elites, general attitudes about the economy, and trust in various media outlets. For supremacism, they included desire for collective action on behalf of Whites, Social Dominance Orientation (Pratto, Sidanius, Stallworth, & Malle, 1994), blatant dehumanization (Kteily, Bruneau, Waytz, & Cotterill, 2015), and the motivations to express bias toward Blacks (Forscher, Cox, Graetz, & Devine, 2015). Finally, we measured characteristics, such as the Dark Triad and self-reported aggression, that might lead to extreme and counter-normative behavior to achieve political ends (Tausch et al., 2011).2

We used two data sources in this project: an exploratory convenience sample using Amazon’s Mechanical Turk and a nationally representative replication sample, which we used to conduct preregistered analyses based on the initial findings from the exploratory MTurk sample. The fact that our replication sample was nationally representative also allowed us to examine the prevalence of alt-right support among the U.S. population and their general demographic profile. In the nationally representative sample, we also assessed support for the Antifa, allowing an exploratory comparison of the psychological correlates of alt-right and Antifa support.

We did not have firm hypotheses for this study due to its exploratory nature. However, based on journalistic and ethnographic (Nagle, 2017) accounts, we had a modest expectation that alt-right adherents would prefer groups that have been historically advantaged in US society (e.g., men, Whites), derogate both disadvantaged minority groups (e.g., Blacks, Muslims) and political outgroups (e.g., Democrats), distrust mainstream institutions, and report characteristics that might cause extremist behavior. We had no specific predictions about just how similar the psychology of non-alt-right Trump supporters would be to alt-right supporters. However, based on research suggesting that support for Trump was motivated by factors such as racial resentment and status anxiety, it seemed plausible that they might have some psychological traits that are similar to the alt-right, and that both the alt-right and Trump voters might differ in similar ways from people who did not vote for Trump. Relatedly, it seemed plausible that the alt-right might be more prevalent among Trump voters than among people who did not vote for Trump.

Method

All data and materials can be found at https://osf.io/xge8q/.

Data sources

We used two data sources: MTurk, which we used to obtain a convenience sample, NORC’s Amerispeak panel, which we used to obtain a larger nationally representative sample. Although we recruited our MTurk sample prior to the representative sample, we focus our primary inferences on the representative sample for two reasons: (1) our primary analyses for the nationally representative sample were preregistered (https://osf.io/u6byt); and (2) the representativeness of this sample allows our analyses to speak to the likely characteristics of the general US adult population. Table 1 displays some basic information about our samples. We provide a detailed analysis of the demographics of the nationally representative sample in the results section.

Table 1.

Our data sources. All percentages are raw (unweighted) estimates.

| Data source | Identification | N | % Trump voters | % Clinton voters |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amerispeak (representative) | Alt-right | 105 | 93.2% | 8.7% |

| Trump voter | 894 | 100.0% | 0.0% | |

| Non-Trump-voter | 284 | 0.0% | 85.8% | |

| MTurk (convenience) | Alt-right | 447 | 74.7% | 5.6% |

| Trump voter | 67 | 100.0% | 0.0% | |

| Non-Trump-voter | 315 | 0.0% | 82.5% |

Amerispeak

To obtain a nationally representative sample, we contracted with a survey company, NORC, to use their Amerispeak panel. Amerispeak is drawn primarily from the NORC national sampling frame, which uses two-stage probability sampling to construct tracts from about 300 housing groups that broadly represent the broader US regions. The Amerispeak panel attains its representativeness from stratified simple random sampling from this national frame. For Amerispeak studies that contain custom design features, one may make additional statistical adjustments to improve representativeness, like using custom survey weights and/or stratification (see the “Complex survey design” section for the additional adjustments we use for this study). Because Amerispeak uses probability sampling, its sampling method allows a stronger claim to representativeness than does “quota sampling”, a non-probability sampling method in which people are sampled on the basis of convenience until fixed quotas of specific subgroups are reached (Rivers, 2004). Amerispeak’s sampling method also has an inferential advantage (albeit a smaller one) over “sample matching”, in which the characteristics of people drawn from a large non-probability sampling frame are matched to the characteristics of a true probability sample; in contrast to these sample matching procedures, no matching is required for an Amerispeak sample to attain representativeness (Rivers, 2004). NORC also has additional procedures to ensure that US groups that are typically suspicious of survey companies (such as conservatives) are adequately represented in Amerispeak; for more details, see https://osf.io/cqvm5/.

We set a goal to recruit at least 100 alt-right supporters. Unlike in our MTurk sample, we avoided mentioning alt-right support as a criterion for study inclusion. However, because we reasoned that the prevalence of alt-right adherents in the U.S. population would likely be low, this strategy forced us to sample a large number of Americans to meet our recruitment goal. To keep the recruitment goal feasible, we oversampled Trump voters on the basis of our prediction that they would have a higher prevalence of alt-right respondents (Schreckinger, 2017).

On the basis of a pilot, we estimated that we would need 1,000 Trump voters to obtain 100 self-professed alt-right respondents. We therefore commissioned NORC to obtain a sample of 1,000 Trump voters and, as an additional comparison sample, 300 people who did not vote for Trump. Our final sample consists of 1039 Trump voters and 309 people who did not vote for Trump, all of whom were at least 18 years old at the time of the survey.

MTurk

For our MTurk sample, we aimed to recruit about 400 each of alt-right and non-alt-right respondents (Schönbrodt & Perugini, 2013). Our advertisement for alt-right respondents specifically asked for alt-right participants, and we offered participants $3 for their participation. We created a second advertisement two weeks later to recruit non-alt-right respondents; we did not mention any inclusion criteria in this ad. To increase our confidence that our samples were who they said they were, we placed identification probes consisting of a single yes/no question that asked the respondents whether they were members of the alt-right at the end of the survey; for the survey that we fielded to recruit alt-right respondents we placed this question at the beginning. We appealed to respondents’ honesty and assured them that they would be compensated regardless of how they responded to the second probe. We also asked some open-ended questions about the alt-right (the data for which are available at https://osf.io/b56xe/). We eliminated anyone gave an answer to the yes/no questions indicating they were not a member of the intended sample.

A total of 480 people in the alt-right dataset identified as alt-right in both identification probes, and 390 in the non-alt-right dataset said they were not alt-right at the second identification probe. We did some additional screening of both datasets using the free response data to ensure each group of people were who they said they were (details available at https://osf.io/b56xe/), resulting in the elimination of 36 people from the alt-right dataset and 8 people from the non-alt-right dataset. This left 447 people from the alt-right dataset and 382 from the non-alt-right dataset for analysis.

Definition of “alt-right support”

Our definition of “alt-right” for the MTurk sample is anyone who answered affirmatively to the two yes/no questions of alt-right identification. In our nationally representative sample, we explored three definitions:

A response of “yes” on the yes/no question of alt-right support

A response above 4 on the 1–7 scale measuring the strength of alt-right support

A response of “yes” on the yes/no question and a response above 4 on the 1–7 scale (a more restrictive definition)

We put our primary focus on the “yes” definition. However, consistent with our preregistration, we explore the robustness of our conclusions by assessing whether results converge across both the other two definitions and those from the MTurk sample.

Procedure

All measures described below were presented in blocks of similarly-themed scales. The order of the blocks was randomized, as was the order of the scales within blocks and, unless otherwise noted, the order of questions within scales. We reduced sets of items that did not already have a previously validated factor structure3 through exploratory factor analysis of the MTurk alt-right sample using scree plots of principal components to decide the number of extracted factors followed by oblimin rotations to decide the variables that loaded on each factor (see https://osf.io/c6r5a/). Once we had collected the nationally representative sample, we spot-checked our MTurk factor analysis results against factor analyses in the new sample. Although these analyses were not directly comparable due to the elimination of some items in the nationally representative sample (see below), the results were similar enough to give us confidence in the scales we had constructed.

Table 2 provides an overview of the measures we included in our surveys, as well as their reliabilities. Many measures are shared across the samples. However, to save time and resources, we compressed many of the measures from the MTurk survey in the survey we fielded to our nationally representative sample. These changes are described in the table and in the sections below. Below we also provide an overview of measures unique to the nationally representative sample. Some measures were unique to the MTurk sample but not discussed in detail here; descriptions of these measures and their data can be found can be found at https://osf.io/d2zxs/

Table 2.

Measures used in the MTurk and nationally representative surveys. In the nationally representative survey, the moral foundations and motivation scales were all administered on 1–7 scales to reduce confusion for respondents. Measures that consist of a single item have their Cronbach’s α left blank.

| mTurk | Representative | |||||||

| Theme | Scale | Items | α | Items | α | Sample | Minimum | Maximum |

| Personal relationships | Closeness | 1–5 | .83 | How close do you feel to each of these friends? | 1 (very distant) | 7 (very close) | ||

| Moral match | 1–5 | .85 | To what extent do the values of each of these friends match your own? | 1 (not at all) | 7 (very much) | |||

| Ideologically embedded | 1–5 | .85 | To what extent does each of these friends identify with the alt-right movement? [non-alt-right: share your political views?] | 1 (not at all) | 7 (very much) | |||

| Interpersonal trust | 1 | About how many people would you trust with matters of deep personal importance? | 0 people | 10+ people | ||||

| Political agreement | 1 | Focusing just on these people (whom you trust with matters of deep personal importance), to what extent do you see eye-to-eye with them politically? | 1 (not at all) | 7 (very much) | ||||

| Personality | Moral foundations: Purity | 2 | .78 | 2 | .69 | People should not do things that are disgusting, even if no one is harmed | 0 (strongly disagree) | 5 (strongly agree) |

| Dark Triad | 12 | .85 | 12 | .70 | Payback needs to be quick and nasty (psychopathy) | 1 (strongly disagree) | 7 (strongly agree) | |

| Intergroup orientation | Social Dominance Orientation | 6 | .89 | 8 | .77 | Some groups of people are simply inferior to other groups | 1 (strongly disagree) | 7 (strongly agree) |

| Right-Wing Authoritarianism | 6 | .81 | Obedience and respect for authority are the most important virtues children should learn | 1 (strongly disagree) | 7 (strongly agree) | |||

| Authoritarianism | 4 | .57 | For each item pair, please select the quality you think is more important for a child to have. [Independence vs Respect for elders] | 0 (no authoritarian) | 4 (all authoritarian) | |||

| Benevolent sexism | 3 | .73 | Women should be cherished and protected by men | 1 (strongly disagree) | 7 (strongly agree) | |||

| Hostile sexism | 3 | .75 | Women exaggerate the problems they have at work. | 1 (strongly disagree) | 7 (strongly agree) | |||

| Nationalism | 2 | .66 | To maintain our country’s superiority, war is sometimes necessary. | 1 (strongly disagree) | 7 (strongly agree) | |||

| Motivations | Express bias (internal) | 3 | .87 | 2 | .82 | My beliefs motivate me to express negative views about Black people | 1 (strongly disagree) | 9; 7 (strongly agree) |

| Express bias (external) | 3 | .88 | 2 | .85 | I minimize my contact with Black people in order to avoid disapproval from others | 1 (strongly disagree) | 9; 7 (strongly agree) | |

| Inhibit bias (internal) | 3 | .87 | 2 | .71 | I am personally motivated by my beliefs to be non-prejudiced toward Black people | 1 (strongly disagree) | 9; 7 (strongly agree) | |

| Inhibit bias (external) | 3 | .91 | 2 | .71 | Because of today’s PC standards I try to appear non-prejudiced toward Black people | 1 (strongly disagree) | 9; 7 (strongly agree) | |

| Dehumanization | Alt-right’s ingroups | 8 | .91 | 7 | .86 | Americans; White people; Republicans; men (all reversed) | 0 (human) | 100 (ape) |

| Religious & national outgroups | 6 | .96 | 6 | .92 | Arabs; Muslims; Mexicans; Black people (all reversed) | 0 (human) | 100 (ape) | |

| Political opposition | 5 | .93 | 5 | .90 | Democrats; feminists; journalists (all reversed) | 0 (human) | 100 (ape) | |

| Reported aggression | Harassment | 5 | .94 | 3 | .81 | Online, physically threatened another person | 1 (not at all frequently) | 7 (very frequently) |

| Offensive | 5 | .92 | 3 | .79 | Online, made a statement because others find it offensive | 1 (not at all frequently) | 7 (very frequently) | |

| Economic optimism | Current | 2 | .59 | 2 | .65 | How would you describe the current economic situation in the US — is it very bad, somewhat bad, somewhat good, or very good? | 1 (very bad) | 4 (very good) |

| Future | 2 | .74 | 2 | .65 | Over the next 12 months, do you expect the national economic situation to worsen a lot, worsen a little, remain the same, improve a little, or improve a lot? | 1 (worsen a lot) | 5 (improve a lot) | |

| Perceived disadvantage | Alt-right’s ingroups | 4 | .84 | White people; men; Republicans; alt-right (all reversed) | 1 (strong disadvantage) | 5 (strong advantage) | ||

| Alt-right’s outgroups | 5 | .89 | Black people; Muslims; Hispanics; women (all reversed) | 1 (strong disadvantage) | 5 (strong advantage) | |||

| mTurk | Representative | |||||||

| Theme | Scale | Items | α | Items | A | Sample | Minimum | Maximum |

| Issue concern | Corruption | 3 | .72 | 3 | .64 | Government corruption; gap between the Washington elites and the common folk | 1 (not at all a problem) | 7 (a big problem) |

| Security | 3 | .72 | 3 | .71 | Islamic terrorism; illegal immigration; crime | 1 (not at all a problem) | 7 (a big problem) | |

| Liberal issues | 3 | .74 | 3 | .76 | Discrimination against Black people; discrimination against women; climate change | 1 (not at all a problem) | 7 (a big problem) | |

| Ingroup discrimination | 2 | .68 | 2 | .74 | Discrimination against White people; discrimination against men | 1 (not at all a problem) | 7 (a big problem) | |

| Speech attitudes | Political correctness | 1 | 1 | Political correctness | 1 (not at all a problem) | 7 (a big problem) | ||

| Liberal speech restriction | 1 | Restrictions on liberal speech | 1 (not at all a problem) | 7 (a big problem) | ||||

| Conservative speech restriction | 1 | Restrictions on conservative speech | 1 (not at all a problem) | 7 (a big problem) | ||||

| Free speech opposition | 2 | .83 | Some views are too dangerous to be aired in public. | 1 (strongly disagree) | 7 (strongly agree) | |||

| Charlottesville blame | Unite the Right | 1 | The people marching with "Unite the Right" | 1 (not at all responsible) | 7 (very responsible) | |||

| Counter-protesters | 1 | The people protesting "Unite the Right" | 1 (not at all responsible) | 7 (very responsible) | ||||

| Police | 1 | The police | 1 (not at all responsible) | 7 (very responsible) | ||||

| Political opinions | Trump support | 1 | Right now, how negative or positive do you feel about Donald Trump? | 1 (very negative) | 7 (very positive) | |||

| Trump job performance | 1 | Overall, how satisfied or dissatisfied are you with President Trump’s job performance? | 1 (very dissatisfied) | 7 (very satisfied) | ||||

| Trump is an alt-right ally | 1 | To what extent do you feel President Trump is an ally of the alt-right movement? | 1 (not at all) | 7 (very much) | ||||

| Muslim ban support | 1 | I support a ban on immigration from Muslim-majority countries. | 1 (strongly disagree) | 7 (strongly agree) | ||||

| Mexico wall support | 1 | I support building a wall between the U.S. and Mexico to prevent illegal immigration. | 1 (strongly disagree) | 7 (strongly agree) | ||||

| Confederate statue removal | 1 | I support the removal of Confederate statues from public spaces. | 1 (strongly disagree) | 7 (strongly agree) | ||||

| Respect for police | 3 | .73 | Police officers don’t get the respect they deserve in this country. | 1 (strongly disagree) | 7 (strongly agree) | |||

| Nostalgic deprivation | 1 | Where would yourself and people like yourself be placed on this diagram? [difference taken between present ratings and ratings for 30 years ago] | −3 (status gain) | 3 (status loss) | ||||

| Trust in institutions | Mainstream media | 10 | .96 | 3 | .93 | CNN; the Economist; the New York Times; the Wall Street Journal | 0 (not trustworthy at all) | 100 (extremely trustworthy) |

| Alternative media | 7 | .89 | 2 | .91 | Fox News; InfoWars; Breitbart; Sean Hannity | 0 (not trustworthy at all) | 100 (extremely trustworthy) | |

| Congress | 1 | Congress | 0 (not trustworthy at all) | 100 (extremely trustworthy) | ||||

| Supreme Court | 1 | The Supreme Court | 0 (not trustworthy at all) | 100 (extremely trustworthy) | ||||

| Big business | 1 | Big business | 0 (not trustworthy at all) | 100 (extremely trustworthy) | ||||

| Collective action | Opposition to BLM | 3 | .73 | 2 | .80 | I support the Black Lives Matter movement. (reversed) | 1 (strongly disagree) | 7 (strongly agree) |

| Support for White action | 5 | .92 | 3 | .82 | More needs to be done so that people remember that “White Lives” also matter. | 1 (strongly disagree) | 7 (strongly agree) | |

Measures shared across the nationally representative and mTurk surveys

Personality characteristics

We measured both moral foundations (Graham et al., 2011) and Dark Triad traits (Jones & Paulhus, 2014).

Moral foundations are theorized to derive from innate psychological mechanisms that can be modified by the social environment. These foundations consist of equality, fairness, loyalty, authority, and purity, which are all measured using the Moral Foundations Questionnaire (MFQ). The short form of the MFQ measures each of these foundations with 4 items (i.e., 20 items total), half of which ask participants to rate their agreement with various statements on a 0 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) scale. We used only these to conserve survey length. Only the purity subscale yielded acceptable reliability in either the representative or the MTurk sample, so we only present that subscale here. The Dark Triad traits consist of narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy, each of which is associated with callous, manipulative behavior (Jones & Paulhus, 2011). The short form of the Dark Triad scale (Jones & Paulhus, 2014) measures each trait using 9 items using a 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) scale. We further shortened these to 4 items each and averaged all items for analysis.

Social Dominance Orientation

We measured Social Dominance Orientation (SDO; Pratto et al., 1994). Social Dominance Orientation (Pratto et al., 1994) assesses how desirable people believe group hierarchy to be. We used six items from the SDO7 scale (Ho et al., 2015), including all four of the dominance sub-dimension and two from the opposition to equality sub-dimension. We examined the overall SDO scale (i.e., as one dimension) in our analyses.

Motivations to express and inhibit bias

These scales consisted of the motivations to express bias toward Blacks (Forscher et al., 2015), and the motivations to respond without bias toward Blacks (Plant & Devine, 1998). Each motivation is further subdivided into an internal (value-driven) motivation and an external (social) motivation, resulting in four subscales: The internal and external motivations to express bias and the internal and external motivations to inhibit bias. Each subscale is measured with five items on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 9 (strongly agree) scale. We shortened this to three and two items, respectively, for the MTurk and nationally representative surveys. In the nationally representative survey, we also shifted the response scale to use 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Dehumanization

We measured blatant dehumanization of various groups using the ascent dehumanization measure (Kteily et al., 2015). This scale asks people to rate how “evolved” they perceive people or groups to be using a diagram shown in Figure 1. People use a 0–100 slider to indicate where a person or group falls on the diagram; higher numbers represent greater humanity. For presentation we reverse-scored these responses so that higher numbers represent greater dehumanization.

Figure 1.

Image used for the ascent scale anchor points.

We assessed dehumanization of a broad array of targets; in the MTurk sample, we had 24, which we shortened to 19 in the nationally representative survey. On the basis of our exploratory factor analysis, we created three subscales measuring dehumanization of (1) the alt-right’s ingroups (Whites, men, Americans, Europeans, the alt-right, Republicans, Donald Trump); (2) the religious and ethnic groups targeted by the alt-right (Mexicans, Nigerians, Arabs, Muslims, Blacks); (3) people and groups that politically oppose the alt-right (Democrats, journalists, the Antifa, Hillary Clinton, feminists). Note that each of these indices had a slightly larger number of targets in the mTurk sample.

Self-reported aggressive behavior

We adapted items from Duggan (2014) to measure the self-reported frequency of online and offline name-calling, physical threats, harassment, and making statements because others find them offensive. We also measured two online-only behaviors: making private information about a person public without their consent (i.e., doxxing) and sharing memes intended to offend others. All self-reported behaviors were measured on a 1 (not at all frequently) to 7 (very frequently) scale. On the basis of our exploratory factor analysis, we created separate subscales assessing harassing behavior (online and offline threats, online and offline harassment, doxxing) and intentionally offensive behavior (online and offline name-calling, online and offline offensive statements, meme-sharing). In the nationally representative survey, we compressed the items asking about online and offline behavior into items that ask about behavior in general (not specifying online or offline).

Attitudes about the economy

We adapted four questions from a survey by Wike, Simmons, Vice, and Bishop (2016). Two of the questions asked the participant to assess each of their personal economic situation and that of the national economy using a 1 (very bad) to 4 (very good) scale. The second asked the participants to rate whether they expected their personal and the national economic situations to get worse or improve using a 1 (worsen a lot) to 5 (improve a lot) scale. On the basis of our exploratory factor analysis, we created separate subscales measuring current and future evaluations of the economy across the personal and national dimensions.

Concern about political issues

We asked participants to rate the extent to which they perceived 12 issues to be a problem in the United States using a 1 (not at all a problem) to 7 (a big problem) scale. On the basis of our exploratory factor analysis, we created four subscales assessing concern about (1) discrimination against the alt-right’s ingroups and allies (discrimination against Whites, discrimination against men), (2) corruption and wealth inequality (government corruption, the gap between the Washington elites and the common folk, the gap between the rich and the poor), (3) security-related issues (illegal immigration, Islamic terrorism), and (4) issues prioritized by liberals (discrimination against Blacks, discrimination against women, climate change). We also examined responses to a single item assessing concern about political correctness, which, when we present in our results alongside other measures assessing free-speech-related constructs.

Media trust

The media questions asked the participants to rate their trust in 22 news media outlets, which we sampled from a report by Mitchell (2014) and supplemented to capture a broad range of ideological lean and media format. Participants rated the extent to which they perceived each outlet as trustworthy using a 0 (not trustworthy at all) to 100 (extremely trustworthy) scale. Participants could select a checkbox labeled “Don’t know” if they were not familiar with a particular media outlet.

On the basis of our exploratory factor analysis, we created separate subscales with 10 and 7 items each that assessed trust in “alternative” and “mainstream” outlets. In our nationally representative survey, we decreased the number of outlets considerably by choosing two and three outlets, respectively, that seemed representative of the mainstream and alternative groupings: CNN and the New York Times (mainstream) and Fox News, Breitbart, and the Rush Limbaugh Show (alternative; see Benkler, Faris, Roberts, & Zuckerman, 2017; Pennycook & Rand, 2019).

Race-based collective action

This category included two scales, one measuring support for collective action on behalf of the interests of White people and a second measuring opposition to the Black Lives Matter (i.e., BLM) movement. Support for White collective action consisted of five items and BLM opposition consisted of two. In contrast to scales that focus primarily on a sense of group cohesion (e,.g., Jardina’s 2019 white identity scale), the items capturing White collective action items also contained elements that indicated a desire to separate Whites from other races (“We need to do more to stop the mixing of the White race with other races”) and advance the political interests of Whites (“I think there are good reasons to have organizations that look out for the interests of Whites”). For the nationally representative survey, we shortened the white action and BLM scales to three and two items, respectively. All items used a 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) scale.

Measures specific to the nationally representative survey

Personal relationships

We used two items to assess different aspects of personal relationships. The item first asked the respondents to name, using a 0 to 10+ scale, the number of people they would trust on matters of deep personal importance. The second asked, using a 1 (not at all) to 7 (very much) scale, the degree to which the respondent saw eye-to-eye with these trusted people.

Authoritarianism

We used an ideologically neutral measure of authoritarianism that allows for comparison across conservative and liberal groups (Hetherington & Weiler, 2009). This measure consists of four items, each of which asks the respondent to pick which of two opposing qualities is more important for a child to have. In all four cases, one of the choices involves a quality favoring rigidity and traditionalism. We summed the number choices favoring rigidity to form a 0–4 authoritarianism index.

Hostile and benevolent sexism

Theoretically, hostile and benevolent sexism stem from three sources of ambivalence toward women, paternalism, gender differentiation, and heterosexuality (Glick & Fiske, 2001). The Ambivalent Sexism Inventory assesses the positive (benevolence) and negative (hostility) feelings that stem from these sources of ambivalence. We chose one item from each of paternalism, gender differentiation, and heterosexuality for both hostile and benevolent sexism, resulting in two three-item subscales assessed on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) scale. We formed averages of the two subscales for analysis.

Nationalism

We included two items assessing a belief in US superiority (adapted from Sidanius, Feshbach, Levin, & Pratto, 1997), each of which was measured using a 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) scale, and computed an average for analysis.

Concern about speech restrictions

In our set of items assessing political concerns, we had two items asking about speech, one assessing concern about restrictions on liberal speech, one assessing concern about restrictions on conservative speech. For both the items, respondents responded using a 1 (not at all a problem) to 7 (a big problem) scale.

Perceptions of Trump

We measured perceptions of Trump with a single item: “Right now, how positive or negative do you feel toward President Donald Trump?” Responses used a 1 (very negative) to 7 (very positive) scale.

Political opinions

We added three items assessing opinions about social policies endorsed by Donald Trump. The items consisted of statements with which respondents rated their agreement using 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) scales. These were: “I support a ban on immigration from Muslim-majority countries”, “I support building a wall between the U.S. and Mexico to prevent illegal immigration”, and “I support the removal of Confederate statues from public spaces” (reverse-coded).

Opposition to free-speech

We averaged responses on two items assessing opposition to free speech for dangerous views: “Some views are too dangerous to be aired in public”, and “Some views need to be shut down by any means necessary” (survey-weighted r = .51).

Blame for Charlottesville

We fielded our representative survey approximately two months after the violence at the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville. We gave our respondents some context about the march: “On August 12 in Charlottesville, Virginia, people marching in rally to ‘Unite the Right’ clashed with people protesting their march. The clashes became violent, 34 people were injured, and one person was killed. In your view, to what extent were the following groups responsible for the violence?” We then asked the respondents to rate the degree to which they blamed the violence on the people marching to “Unite the Right”, the people protesting against “Unite the Right”, and the police using a 1 (not at all responsible) to 7 (very responsible) scale.

Nostalgic deprivation

Gest and colleagues (2017) proposed that feelings of feelings of social, economic, and political deprivation drive support for the radical right and developed a measure of “nostalgic deprivation” to assess this. Respondents view a series of concentric circles and are asked to select the in the circle that they think best represents the place in society for themselves and people like themselves; see Figure 2. Respondents then repeat this task focusing on how they think things were 30 years ago. We assessed nostalgic deprivation by taking the difference between the past and present centrality ratings; positive values represent perceptions of status loss and negative values represent perceptions of status gain.

Figure 2.

The series of circles used to measure nostalgic deprivation

Trust in institutions

In addition to asking about trust in media, in the representative survey we asked respondents to rate, using 0 (not at all) to 100 (very much) scales, the degree to which they trusted Congress, the Supreme Court, and big business.

Results

Data analytic plan

Our primary interest centered on our preregistered comparisons between the alt-right sample and both the non-alt-right Trump voters and non-alt-right people who did not vote for Trump. We made these comparisons using two dummy-coded contrasts with the alt-right as the reference group. We also conducted more exploratory comparisons between the Trump voters and the non-Trump voters to help contextualize the results, and to evaluate the extent to which non-alt-right supporting Trump voters appeared more similar to alt-right adherents vs. non-Trump voters. We placed primary focus on the “yes/no” definition of alt-right support in the nationally representative dataset; we examine the alternative definitions and the MTurk sample as part of our robustness analyses, reported in full below.

Complex survey design

Our use of a complex survey design in our nationally representative sample demanded special procedures to ensure that we could properly make inferences about the US population of alt-right adherents. To this end, in any analyses using the nationally representative dataset, we used weights proportionate to the inverse of the probability of selection from the NORC national sampling frame/address-based sample. These survey weights were further adjusted for non-response and raked to current US population totals (Little, 1993). Due to the fact that we oversampled Trump voters relative to non-Trump voters, we also stratified by voter status in all analyses (Little, 1993).

The survey weights ensure less bias in population estimates at the cost of increased variance, and therefore a lower effective sample size. The degree to which the survey weights lower the effective sample size is measured using the so-called “design effect”. Design effects are generally larger for estimates of rare characteristics, like alt-right support among non-Trump voters (Kalton, 2009).

At the time of preregistration, we consulted with a senior statistician at NORC about ways to control the size of the design effect. One way is to remove from our sample any alt-right-adherents among the non-Trump-voting sample. We expected (and found, see Table 1) these people to be rare, with a correspondingly harsh impact on the design effect (see some simulation evidence at https://osf.io/cqvm5/). To this end, we requested that NORC prepare a set of three weights, one per definition, that set the prevalence of non-Trump-voting alt-right respondents to 0. We use these weights for our preregistered comparisons between alt-right adherents, non-alt-right Trump voters, and non-alt-right non-Trump-voters. We also asked NORC to prepare a fourth set of weights for which all respondents are included. We use these weights to estimate demographic characteristics of the samples and the national prevalence of alt-right support.

Prevalence of alt-right support

We used the survey-weighted estimates from the nationally representative sample to obtain estimates of the prevalence of alt-right adherents using our three definitions of “alt-right”. These results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Estimates of the prevalence of the alt-right under three definitions: (1) a “yes” response to a yes/no question about alt-right identification; (2) a response above 4 on a 1–7 scale measuring degree of identification; and (3) both a “yes” response and a response above 4 on the above two questions.

| Overall | Trump voters | Non-Trump-voters | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | |

| Yes/No | 6.2% | [4.8%, 8.1%] | 10.0% | [7.9%, 12.5%] | 3.0% | [1.4%, 6.6%] |

| Quantitative | 11.6% | [9.3%, 13.5%] | 19.1% | [16.0%, 22.6%] | 5.5% | [2.7%, 10.8%] |

| Strict | 4.0% | [2.8%, 5.6%] | 6.9% | [5.1%, 9.0%] | 1.5% | [0.4%, 5.5%] |

We estimate that approximately 6.2%, 95% CI = [4.8%, 8.1%] of US adults would respond “yes” on a yes/no question of alt-right support. A somewhat higher percentage, 11.6%, 95% CI = [9.3%, 13.5%], would give a response above the midpoint on a 1–7 scale measuring degree of identification with the alt-right. A lower percentage — 4.0%, 95% CI = [2.8%, 5.6%] — would both respond “yes” on a yes/no question of alt-right support and respond above the midpoint of the alt-right identification scale. All these estimated percentages are higher among 17Trump voters and lower among non-Trump-voters. Taking our most conservative estimate as a lower bound, these results suggest that at least 3% of the general population are alt-right supporters, and 5% of US Trump voters are alt-right supporters

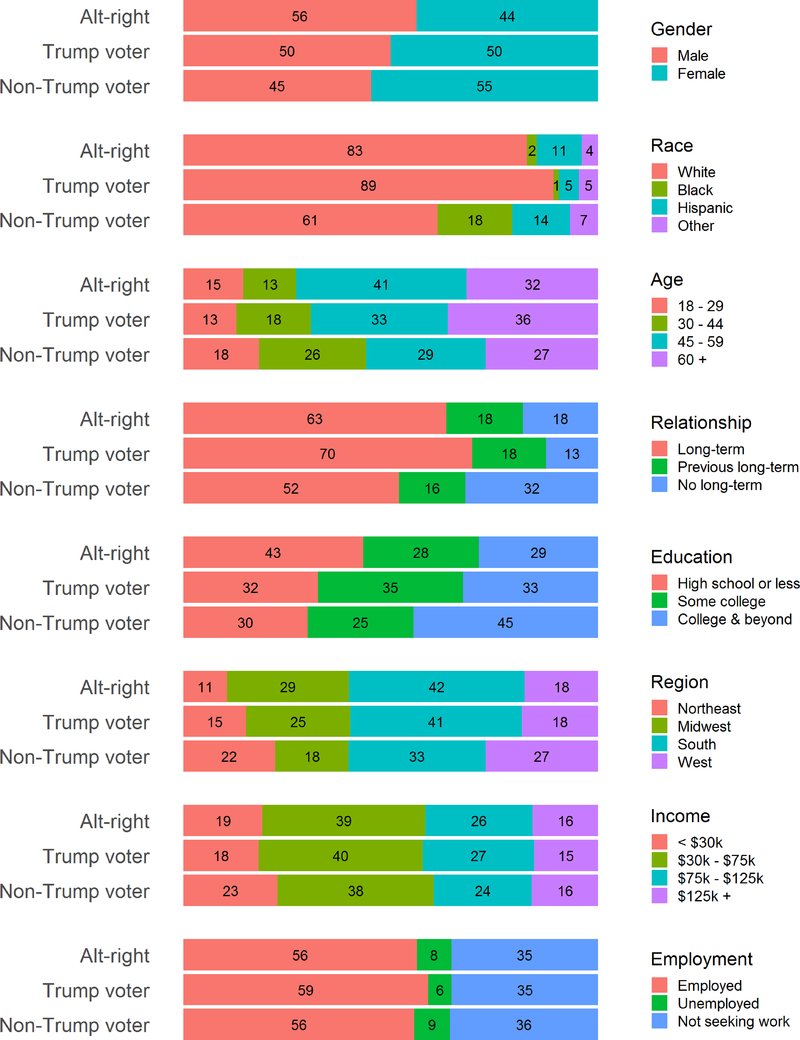

Detailed demographics

The nationally representative sample gave us an opportunity to examine the demographics of the alt-right. Figure 3 shows these demographics using the yes/no definition; Figure 4 examines how statistical comparisons of alt-right to non-alt-right vary across definitions of “alt-right”. Alt-right respondents were highly similar demographically to (non-alt-right) Trump voters; there were no significant differences between the alt-right and Trump voters that were robust to alternative definitions of “alt-right”. Both Trump voters and alt-right supporters differed demographically from non-Trump voters: regardless of definition, both samples were significantly Whiter and more likely to come from the Midwest. Moreover, both Trump voters and alt-right adherents (across two definitions, at least) were less likely than non-Trump voters to have a college education or beyond.4

Figure 3.

Demographic breakdown of the alt-right, Trump-voting, and non-Trump-voting samples (yes/no definition). Numbers in bars are survey-weighted percentage estimates. “Income” = Household income.

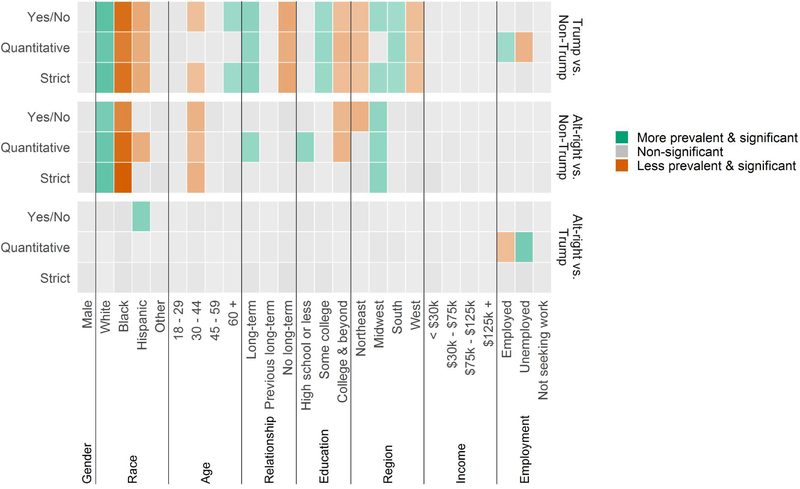

Figure 4.

Robustness of the differences in demographic prevalence across three definitions of “alt-right”. Each rectangle represents whether the demographic in question was significantly more prevalent in the first listed sample (green), significantly less prevalent (maroon), or not significantly different across samples. All statistical tests come from survey-weighted Generalized Linear Models with binomially distributed error and logit links with stratification across voting status.

Comparisons of survey measures

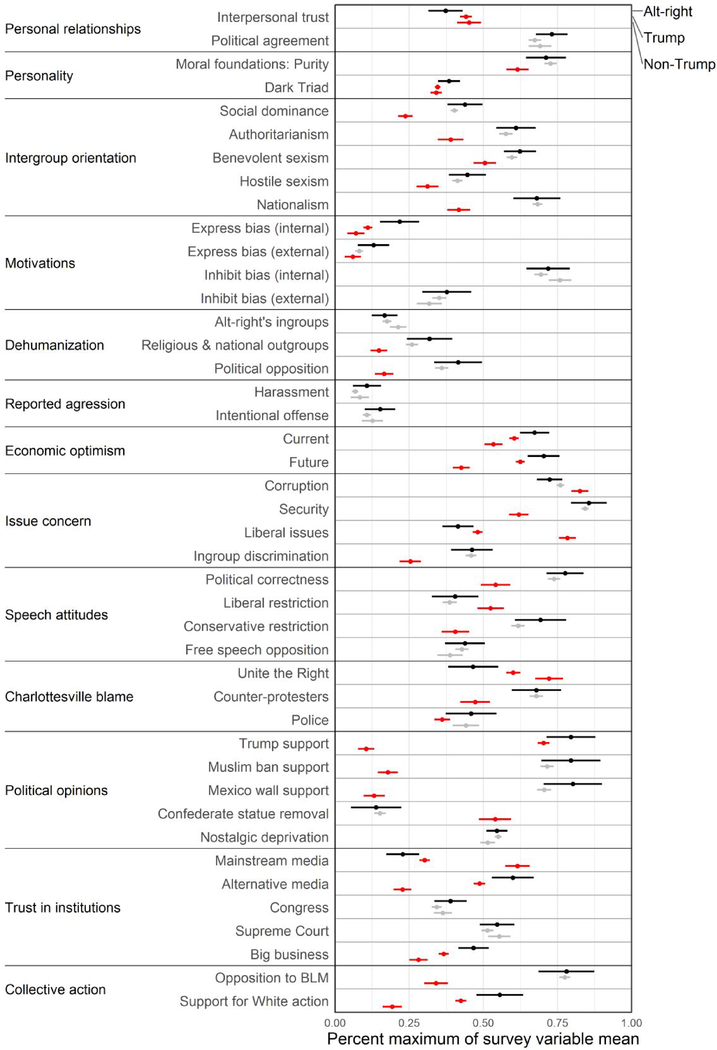

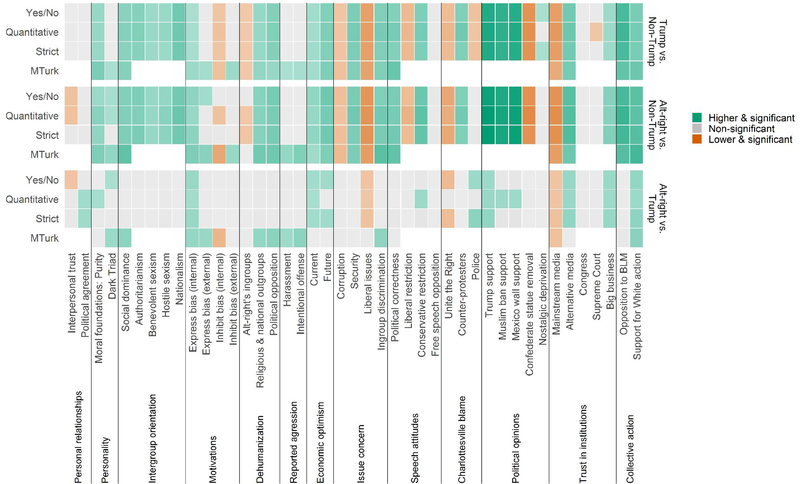

Alt-right supporters differed from (non-alt-right) non-Trump supporters across the vast majority of the outcomes that we assessed in our surveys (see Figures 5 and 6). Moreover, results tended to converge across definitions and samples. Where results diverged, the representative sample tended to be more conservative about where it indicated differences between the alt-right and other samples.

Figure 5.

Survey-weighted estimates and 95% CIs of survey responses from the alt-right and the two non-alt-right samples. Estimates come from the nationally representative sample and use the yes/no alt-right definition. All estimates are scaled in terms of the percent of the maximum possible scale response. Black dots are estimates from the alt-right respondents; red dots indicate that the estimate in question is significantly different from the alt-right estimate; grey indicates no significant difference.

Figure 6.

Robustness of the differences across alt-right, Trump voters, and non-Trump voters across the MTurk and nationally representative samples, with three possible definitions of “alt-right supporter” in the nationally representative sample. A grey rectangle indicates the comparison in question was non-significant, maroon indicates the second group was lower and significantly different, green indicates the second group was higher and significantly different. The degree of transparency in the rectangles is proportionate to the size of the difference; the more visible the larger.

More specifically, across definitions and samples, alt-right supporters were significantly higher than non-alt-right non-Trump supporters on (1) purity concerns, dark triad traits, authoritarianism, social dominance orientation, the internal and motivation to express bias toward Black people, hostile and benevolent sexism, nationalism, and blatant dehumanization of derogated and opposition groups; (2) support for Trump and policies of his such as the Muslim ban and building a wall between the U.S. and Mexico; (3) concerns about each of security, discrimination against ingroups (i.e., discrimination against Whites and men), political correctness, and restrictions to conservative speech; (4) trust in alternative media and business; and (5) opposition to Black Lives Matter and support for white collective action. Alt-right supporters were significantly lower than people who did not vote for Trump on (1) the number of people they reported trusting; (2) their support for removing confederate statues, concerns about liberal issues (i.e., discrimination against Black people and women; climate change) and (3) concerns about restrictions to liberal speech and trust in mainstream media. Interestingly, and in contrast to popular intuitions (Daniszewski, 2016; Guardian style editors, 2016), alt-right supporters were also significantly lower than non-alt-right non-Trump supporters on concerns about corruption and optimism about the economy.

The alt-right and non-Trump voters differed extensively. Indeed, the only constructs on which we did not observe differences between them were (1) the motivations to inhibit bias toward Blacks (both internal and external) and dehumanization of the alt-right’s ingroups; (2) opposition to free speech; (3) the degree of reported political agreement with friends; (4) self-reported harassing and offensive behavior; (5) feelings of nostalgic deprivation; and interestingly, (6) trust in national institutions such as Congress and the Supreme Court.

By comparison, there were far fewer differences between alt-right adherents and the non-alt-right Trump supporters. Alt-right supporters were significantly higher than Trump supporters on (1) the desire to express bias toward Black people for value-based reasons; (2) optimism about the economy, trust in business, and trust in alternative media; and, interestingly, (3) support for Donald Trump and (4) desire for collective action on behalf of Whites. They were also lower in concern about liberal issues, trust of the mainstream media, and in the number of people they reported trusting deeply. For all other variables, we observed no significant differences between alt-right supporters and non-alt-right Trump supporters.

There were several constructs where the alt-right and (non-alt-right) Trump voters were both similar to one another and different from the (non-alt-right) non-Trump-voters, namely (1) social dominance orientation, authoritarianism, benevolent and hostile sexism, nationalism, blatant dehumanization; (2) support for the Muslim ban, a wall with Mexico, and opposition to removing confederate statues; (3) opposition to Black Lives Matter, and (4) concerns about security, political correctness, and discrimination against the ingroup. The majority of these constructs were related to the desire for certain groups (e.g., Americans, men, and whites) to dominate other groups (e.g., immigrants, women, and non-white ethnic and racial minorities).

Some of the differences we observed were dramatic. For example, alt-right supporters rated their agreement with items like “Whites need to start looking out more for one another” and “We need to do more to stop the mixing of the White race with the other races” at 4.3, just above the scale midpoint, and non-alt-right Trump voters rated their agreement at 3.5, a bit below the midpoint. In contrast, non-Trump-voters rated their agreement with these kinds of items at 2.2, just above “strongly disagree”. The difference between the alt-right and non-Trump-voters in agreement with these items is 35% of what is possible on a 1–7 scale; the difference between Trump voters and non-Trump-voters is 22% of what is possible.

On some variables we observed no differences between any of the groups. Specifically, there were no differences on (1) the internal or external motivation to inhibit bias toward Black people; (2) dehumanization of the alt-right’s ingroups; (3) self-reported harassing and offensive behavior; (4) general opposition to free speech; and (5) trust in Congress and the Supreme Court.

In sum, alt-right supporters appeared psychologically similar to non-alt-right Trump supporters, and both groups appeared largely dissimilar from non-Trump voters. The alt-right supporters were only distinctive from the non-alt-right Trump voters in a small number of ways, including their extreme distrust of mainstream media and preference for alternative media, their strong support for Trump, and their strong support for collective action on behalf of Whites. The exact pattern of similarities and differences across all three groups supports an account of both the alt-right and non-alt-right Trump voters as desiring group-based dominance. There was little evidence to support an account of the alt-right as anti-establishmentarian; the main evidence to this effect was the alt-right’s high levels of suspicion of mainstream media. In fact, many of the differences we observed directly contradict an anti-establishmentarian account, including the alt-right’s high levels of economic optimism and low levels of concern about corruption.

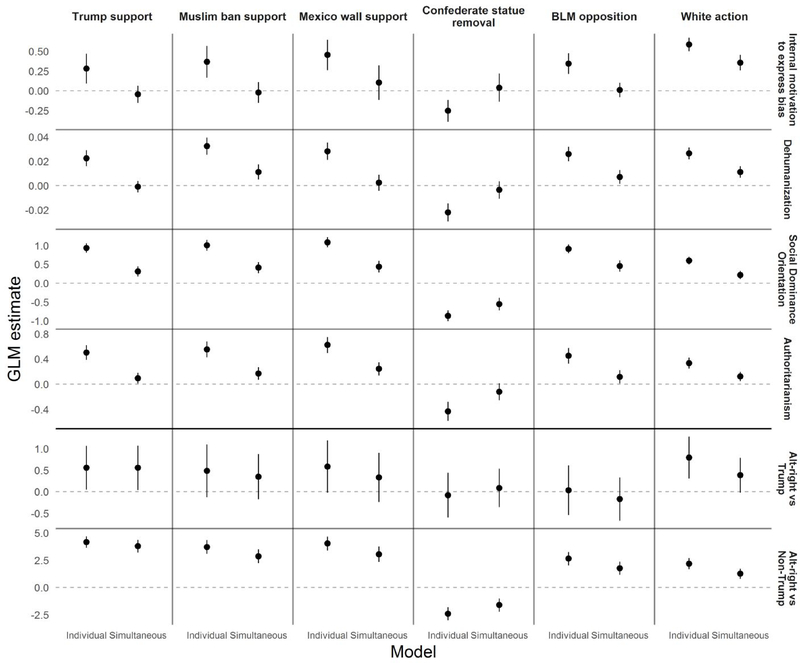

Exploratory regression analyses

According to the preceding analyses, much of what distinguishes the alt-righters from non-alt-righters is the alt-right’s favorability toward actions and policies that have the effect of protecting the interests of Whites. To better understand what might be driving this favorability, we conducted exploratory regression analyses to determine which, of several potential predictors, might be uniquely associated with favorability toward these actions and policies. Due to the cross-sectional design of our surveys, these analyses cannot speak strongly to cause. Nevertheless, these analyses can generate new hypotheses which can serve as a springboard for future studies that can support stronger causal inference.

In all the analyses we present, we focused on the nationally representative sample and the yes/no definition of alt-right support. As outcomes, we focused on the desire for White collective action, opposition to Black Lives Matter, support for a Muslim ban, support for a wall with Mexico, opposition to taking down Confederate statues, and support for Trump himself. As predictors, we chose variables that have been highlighted as plausibly important in explaining the derogation of minority groups and/or the support for policies aimed at group dominance. These included social dominance orientation (Ho et al., 2015), the dehumanization of ethnic and religious minority groups (Mexicans, Nigerians, Arabs, Muslims, and Blacks; Kteily et al., 2015), authoritarianism (Hetherington & Weiler, 2009), and the internal (value-based) motivation to express bias toward Black people (Forscher et al., 2015)5. We also included our two dummy-coded indicators that compare the alt-right to Trump voters and non-Trump-voters, respectively. For each outcome, we fit regression models that only included one of the predictors and that included all of them simultaneously. If, for a given outcome, the coefficient for a dummy code is reduced in the simultaneous model relative to the individual model, this tentatively suggests that the set of psychological predictors help explain why alt-right and non-alt-right participants differ on the outcome.

The results are shown in Figure 7. In the individual models, the motivation to express bias, dehumanization, social dominance, and authoritarianism were all associated with each of the outcomes. In the simultaneous models, only social dominance orientation remained associated all of the political/policy outcomes. Authoritarianism and dehumanization remained uniquely associated with many of the outcomes, with the exception of Confederate statue removal (for authoritarianism) and both Confederate statue removal and Trump support (for dehumanization). The internal (value-based) motivation to express bias only remained associated with the desire for collective action on behalf of Whites people.

Figure 7.

Regression analyses with the nationally representative sample (yes/no definition of alt-right). Each column represents a regression outcome, each row a predictor. In the “Individual” models, only the predictor was regressed on the outcome; in the “Simultaneous” models, all predictors were regressed on the outcome simultaneously. “Alt-right vs Trump” and “Alt-right vs Non-Trump” represent dummy-coded indicators for these comparisons. The coefficients for two dummy-codes are scaled such that higher values indicate that the alt-right is higher than the sample to which it is being compared.

We also examined the difference in the dummy code coefficients across the individual and simultaneous models using survey-weighted Structural Equation Modeling in the lavaan.survey package (Oberski, 2014). Across all outcomes, the decreases from the individual to simultaneous models for the coefficient representing the difference between the alt-right and non-Trump-voters were non-zero (Trump support: ab = −.38, 95% CI = [−.62, −.14]; Muslim ban support: ab = −.80, 95% CI = [−1.15, −.45]; support for wall with Mexico: ab = −.83, 95% CI = [−1.24, −0.41]; support for Confederate statue removal: ab = .76, 95% CI = [.33, 1.20]; opposition to Black Lives Matter: ab = −.74, 95% CI = [−1.06, −.42]; support for collective action on behalf of Whites: ab = −0.81, 95% CI = [−1.11, −.52]). In contrast, the only outcome for which the decrease in the dummy coefficient representing the difference between the alt-right and Trump voters was significant was support for collective action on behalf of Whites exhibited a significant decrease, ab = −.30, 95% CI = [−.54, −0.05].

In sum, our exploratory regression results tentatively suggest that social dominance, authoritarianism, dehumanization, and the value-based motivation to express bias may jointly explain part why the alt-right differ from non-Trump-voters. However, these predictors were largely unable to explain differences between the alt-right and Trump voters – possibly because there were fewer differences between the alt-right and Trump voters to begin with. The one exception to this pattern was the desire for White collective action; our predictors explained about half of the difference between the alt-right and Trump voters.

Exploratory comparisons between the alt-right and Antifa

Our measurement of both alt-right and Antifa identification in our nationally representative sample gave us the chance to explore the degree of similarity or difference in their psychology. On the one hand, these two groups are on the opposing ends of the ideological spectrum, so one would expect to find differences in the direction of the association between support for each of these groups and ideologically-relevant outcome measures (e.g., concern about liberal issues). On the other hand, the extent to which support for each of the groups is similarly associated with outcomes such as a willingness to engage in harassment or levels on traits such as authoritarianism or the Dark Triad remains an open question. To the extent that the alt-right and the Antifa are comparably extremist — and that right-wing and left-wing extremists are similarly disposed towards violence and authoritarianism — one would expect support for each of these two groups to be comparably correlated with relevant traits (see van Prooijen & Kouwel, 2019).

Although we asked for Antifa identification in our survey, our sampling plan was designed to maximize the number of alt-right rather than Antifa adherents. Indeed, only 47 of our respondents gave a “yes” response to the yes/no question about Antifa identification, limiting the precision with which we can estimate the characteristics of the Antifa. However, the fact that we gathered the 1–7 scale asking for degree of identification with the Antifa allows us to use an alternative strategy to compare the correlates of alt-right vs Antifa identification: compare the survey-weighted correlates of the two 1–7 scales of alt-right and Antifa identification.

Table 4 displays these correlations, with p-values representing a test of the difference (using survey-weighted SEM with stratification by voting status, implemented in lavaan.survey; Oberski, 2014). We focus here on a few particularly noteworthy comparisons. As expected, the relationships between ideologically-relevant outcomes and support for the alt-right and Antifa differed, often dramatically. For example, support for the alt-right was positively correlated strongly with Trump support and support for the Mexico wall (rs = .48 and .47, respectively), while support for Antifa was correlated with these variables at a similar magnitude but in the opposite direction (rs = −.37 and −.37, respectively). We found similar patterns for concern about liberal issues, political correctness, the Muslim ban, Black Lives Matter opposition and support for removing confederate statues. Unsurprisingly, support for the two groups was also oppositely associated with blaming marchers versus counter-protestors for the events in Charlottesville. Perhaps more surprisingly, although support for the two groups was oppositely associated with feelings about White collective action, the positive link between support for the alt-right and support for White collection action (r = .46) was notably stronger in magnitude than its negative association with Antifa support (r = −.16), χ2(1, N = 1345) = 25.34, p < .001.

Table 4.

Correlations between alt-right and Antifa identification and the other survey variables; p-values are tests of the difference in correlations, obtained using a survey-weighted SEM with stratification by voting status.

| Identification | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alt-right | Antifa | p | ||

| Personal relationships | Interpersonal trust | −0.13 | 0.03 | 0.017 |

| Political agreement | 0.01 | 0.1 | 0.06 | |

| Personality | Moral foundations: Purity | 0.14 | −0.26 | 0 |

| Dark Triad | 0.3 | 0.06 | 0.012 | |

| Intergroup orientation | Social dominance | 0.43 | −0.22 | 0 |

| Authoritarianism | 0.28 | −0.2 | 0 | |

| Benevolent sexism | 0.17 | −0.09 | 0.001 | |

| Hostile sexism | 0.27 | −0.13 | 0 | |

| Nationalism | 0.33 | −0.22 | 0 | |

| Motivations | Express bias (internal) | 0.36 | 0.04 | 0.008 |

| Express bias (external) | 0.26 | 0.06 | 0.116 | |

| Inhibit bias (internal) | −0.2 | 0.01 | 0.002 | |

| Inhibit bias (external) | 0.1 | −0.05 | 0.06 | |

| Dehumanization | Alt-right’s ingroups | −0.05 | 0.14 | 0.037 |

| Religious & national outgroups | 0.26 | −0.02 | 0 | |

| Political opposition | 0.27 | −0.17 | 0 | |

| Reported aggression | Harassment | 0.28 | 0.14 | 0.347 |

| Intentional offense | 0.25 | 0.09 | 0.243 | |

| Economic optimism | Current | 0.08 | −0.01 | 0.225 |

| Future | 0.24 | −0.25 | 0 | |

| Issue concern | Corruption | −0.24 | −0.01 | 0.014 |

| Security | 0.31 | −0.36 | 0 | |

| Liberal issues | −0.4 | 0.36 | 0 | |

| Ingroup discrimination | 0.39 | −0.22 | 0 | |

| Speech attitudes | Political correctness | 0.22 | −0.42 | 0 |

| Liberal restriction | −0.04 | 0.19 | 0.001 | |

| Conservative restriction | 0.37 | −0.29 | 0 | |

| Free speech opposition | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.829 | |

| Charlottesville blame | Unite the Right | −0.34 | 0.23 | 0 |

| Counter-protestors | 0.23 | −0.35 | 0 | |

| Police | 0 | 0.06 | 0.881 | |

| Political opinions | Trump support | 0.48 | −0.37 | 0 |

| Muslim ban support | 0.47 | −0.31 | 0 | |

| Mexico wall support | 0.47 | −0.37 | 0 | |

| Confederate statue removal | −0.4 | 0.33 | 0 | |

| Nostalgic deprivation | −0.04 | −0.07 | 0.282 | |

| Trust in institutions | Mainstream media | −0.36 | 0.44 | 0 |

| Alternative media | 0.41 | −0.31 | 0 | |

| Congress | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.906 | |

| Supreme Court | −0.04 | 0.04 | 0.101 | |

| Big business | 0.2 | −0.1 | 0 | |

| Collective action | Opposition to Black Lives Matter | 0.38 | −0.44 | 0 |

| Support for White action | 0.46 | −0.16 | 0 | |

Importantly, the differences between the two groups were not restricted to partisan issues. Whereas alt-right identification was positively associated with an ideology-free measure of authoritarianism (r = .28), the reverse was true for Antifa identification (r = −.20). Support for the alt-right was associated with more agreement with items like “some groups should dominate other groups” (social dominance orientation; r = .43), whereas support for the Antifa was associated with less (r = −.22). It therefore appears that Antifa support does not reflect authoritarianism or endorsement of the principle of intergroup dominance to the same extent as alt-right support.

That said, on some dimensions the correlates of identification with the two groups were more similar than different. Support for both groups had similar associations with the degree of political agreement with trusted others (ralt-right = .01; rAntifa = .10). Similarly, support for both groups had similar (positive) associations with self-reported harassment (ralt-right = .28; rAntifa = .14) and intentionally offensive behavior (ralt-right = .25; rAntifa = .09). The magnitude of the correlation of alt-right identification with dehumanization of religious and national outgroups (who might be considered the Antifa’s ingroups, ralt-right = .26) was not substantially different from the magnitude of the correlation of Antifa identification with dehumanization of the alt-right’s in-groups (rAntifa = .14). Intriguingly, although support for the two groups had different (and opposite) associations with concern about political correctness, restrictions on liberal speech, and restrictions on conservative speech, they had highly similar associations with overall opposition to free speech (ralt-right = .06; rAntifa = .08; Crawford & Pilanski, 2014).

Finally, we obtained exploratory estimates of the prevalence of Antifa support; see Table 5. The prevalence of Antifa support was broadly similar to the prevalence of alt-right support. The one exception was that, whereas Antifa support was more prevalent among non-Trump-voters, alt-right support was more prevalent among Trump voters.

Table 5.

Estimates of the prevalence of the Antifa under three definitions: (1) a “yes” response to a yes/no question about Antifa identification; (2) a response above 4 on a 1–7 scale measuring degree of identification; and (3) both a “yes” response and a response above 4 on the above two questions.

| Overall | Trump voters | Non-Trump-voters | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | |

| Yes/No | 6.9% | [4.8%, 9.7%] | 1.6% | [0.7%, 3.4%] | 11.6% | [7.8%, 16.8%] |

| Quantitative | 12.4% | [9.1%, 16.7%] | 2.8% | [1.8%, 16.7.6%] | 21.6% | [15.3%, 29.4%] |

| Strict | 3.4% | [2.0%, 5.9%] | 0.5% | [0.2%, 1.2%] | 6.2% | [3.5%, 10.8%] |

In sum, then, although the strength and direction of the correlations of alt-right and Antifa support were similar on a few variables, such as self-reported harassing and intentionally offensive behavior, many correlations were different. This evidence tentatively suggests that the correlates of alt-right support may differ from the correlates of Antifa support, both in partisan issues and at least some dispositional variables. In particular, Antifa support appears to be associated with less authoritarian and socially domineering tendencies than is alt-right support.

Discussion

Portrayals of the alt-right vary widely. Some of these portrayals emphasize the movement’s anti-globalist and anti-establishment views (Bokhari & Yiannopoulos, 2016; Guardian style editors, 2016), while others emphasize its interest in maintaining structures of group-based dominance and supremacy (Armstrong, 2017; Caldwell, 2016; Gest et al., 2017; Lyons, 2017). Employing a nationally representative random probability sample, we conducted the first quantitative empirical examination of the psychological profile and prevalence of the alt-right, comparing them to both non-alt-right supporting Trump voters and (non-alt-right supporting) non-Trump voters. We found some evidence for the anti-establishment portrayal: Alt-right supporters expressed more suspicion of mainstream media and trust in alternative media compared to both non-alt-right Trump voters and non-Trump-voters. However, we found little evidence that these anti-establishment tendencies extended to economic issues: Compared to both Trump voters and non-Trump-voters, alt-right supporters were both more optimistic about current and future states of the economy and more trusting of big business. These results accord with research suggesting that changes in people’s material circumstances have little to do with support for far-right political movements (Gidron & Mijs, 2019; Mutz, 2018) and are less consistent with evidence linking extremism or support for far-right parties to socio-economic anxiety (R. Ford & Goodwin, 2010; van Prooijen, Krouwel, Boiten, & Eendebak, 2015).

In contrast, we found abundant support for portrayals of the alt-right that emphasize their belief in and desire to advance the supremacy of dominant groups such as Whites at the expense of less dominant groups. Compared to non-Trump-voters, the alt-right were relatively concerned about discrimination toward White and men, more willing to dehumanize historically disadvantaged groups and groups that might politically oppose the alt-right, and higher in sexism, authoritarianism and social dominance orientation. Compared to both non-Trump-voters and Trump voters, the alt-right expressed high levels of support for collective action on behalf of Whites and internal (value-based) motivation to express bias toward Black people.

Although the alt-right differed markedly from non-alt-right non-Trump-voters, they appeared in many ways more similar to than different from non-alt-right Trump voters. Demographically, the alt-right and Trump voters were similar: both were Whiter, older, less likely to be highly educated, and more likely to hail from the Midwest than were non-Trump-voters. Psychologically, both groups reported similar high levels of social dominance and authoritarian tendencies, hostile and benevolent sexism, and concern about discrimination toward Whites and men. To the extent that alt-right adherents differed from Trump voters, they showed a profile consistent with the view that they are particularly enthusiastic Trump supporters: they were particularly favorable toward Trump and suspicious of the institutions and groups that Trump has a history of attacking, such as mainstream media outlets. The alt-right also expressed striking support for collective action to benefit the interests of Whites. Compared to non-Trump-voters, alt-right adherents were 2.18 scale points more favorable toward White collective action, representing 36% of the maximum possible difference on a 1–7 scale. Alt-right adherents were also still more favorable toward White collective action than were Trump voters, though the difference was somewhat smaller (.79), representing 13% of the maximum possible difference.

Our regression analyses highlight some possible reasons why the alt-right might have a greater preference for policies that benefit majority groups at the expense of ethnic and racial minority groups. Specifically, we considered whether the inclusion of a range of psychological constructs helped to statistically account for differences between the alt-right and each of the non-Trump and Trump voters. When comparing the alt-right to non-Trump-voters, we observed that the alt-right’s greater support for policy preferences (e.g., the Muslim ban, opposition to the removal of confederate statues) might stem from a mixture of greater social dominance, authoritarianism, the dehumanization of religious and national out-groups, and value-based motivation to express bias, each of which were uniquely associated with at least one policy preference (and accounted for part of the difference between alt-right and non-Trump voters on the respective policy). Consistent with their psychological similarity, there were fewer significant differences on policy outcomes to explain between alt-right supporters and Trump voters. Nevertheless, these same psychological variables helped to statistically account for alt-right adherents’ greater favorability toward White collective action.

Our findings also have broader implications for the psychological study of intergroup bias. Despite psychology’s rich history of examining intentional and/or blatant intergroup bias (e.g., Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswik, Levinson, & Sanford, 1950; Adorno et al., 1950; Pettigrew, 1958; Westie, 1964), research on intergroup relations and social cognition over the past several decades has focused on the more subtle and implicit forms of intergroup bias (Dovidio, Kawakami, & Gaertner, 2002; for discussion, see Forscher & Devine, 2016; Kteily & Bruneau, 2017). This pattern suggests an unstated — and, perhaps, unduly optimistic — assumption that blatant intergroup bias is a feature of a bygone past. Indeed, even our most conservative estimates place alt-right support at a non-negligible proportion of U.S. society, and our results highlight the overt nature of their bias. Non-alt-right Trump voters represent a still larger segment of the general population, and thus, the fact that we find such few differences between alt-right supporters and non-alt-right Trump voters further supports the continuing relevance of blatant intergroup attitudes6. So too does a growing body of research suggesting the contemporary relevance of white identity (Jardina, 2019) and perceived status threats to the white majority (Craig & Richeson, 2014). What are the factors that are associated with change in blatant intergroup bias? How much does blatant intergroup bias change over the lifespan? What determines whether blatant intergroup bias manifests in support for organizing on behalf of a political movement? These are deep and pressing questions that deserve sustained scholarly scrutiny, and may require re-balancing our research agenda to place greater attention back on blatant and explicit as well as subtle and implicit processes.

A final noteworthy contribution of our research was our exploratory comparison of the psychological bases of alt-right identification and identification with another extremist group, the Antifa. Our results tentatively suggest that the roots of support for these two groups may be distinct. van Prooijen and Kouwel (2019) suggest that both left-wing and right-wing extremism are similarly characterized by psychological distress, simplistic thinking, overconfidence, and intolerance. Although our surveys did not contain measures of overconfidence and simplistic thinking, we did have measures that speak to some elements of intolerance and distress, including dehumanization, economic optimism, and concern about corruption and political correctness. Alt-right and Antifa identification had different associations with economic optimism, concern about corruption, and concern about political correctness (with Antifa support associated with relatively more concern in all cases). Alt-right identification was also more strongly associated than Antifa identification with both an ideology-free measure of authoritarianism and with support for the principle of intergroup dominance (i.e., social dominance orientation). One place where the alt-right and Antifa were more similar was in dehumanization: although they dehumanized different targets, the degree to which alt-right and Antifa identification were correlated with dehumanization of their favored targets was similar (Crawford & Pilanski, 2014; Ditto et al., 2019).

Caution is warranted in interpreting our comparisons between the Antifa and the alt-right. We did not explicitly sample Antifa supporters; our sample of Antifa is thus small, and our estimates of their psychological characteristics are correspondingly imprecise. Moreover, because our research was not centrally focused on comparing the cognitive profile of left and right-wing extremism, we only had a limited subset of variables relevant to that question. Future research should more systematically examine Antifa support and compare it to alt-right support on other constructs linked to extremism such as simplistic thinking (Lammers, Koch, Conway, & Brandt, 2017) and overconfidence (Brandt, Evans, & Crawford, 2015).

Limitations