Abstract

Male sex workers in Kenya face a disproportionate burden of HIV and often engage in condomless sex with their commercial partners, yet little is known about how condom negotiations between male sex workers and clients take place. We conducted semi-structured interviews with 25 male sex workers and 11 male clients of male sex workers in Mombasa, Kenya, to examine barriers and facilitators to condom use and how condom negotiation takes place in these interactions. Participants reported positive attitudes toward condom use and perceived condom use to be a health-promoting behavior. Barriers to condom use included extra-payment for condomless sex, low perceived HIV/STI risk with some sexual partners, perceived reduced pleasure associated with using condoms, alcohol use, and client-based violence against male sex workers. Future interventions should address individual- and structural-level barriers to condom use to promote effective condom negotiation in interactions between male sex workers and male clients.

Keywords: Men who have sex with men, Male sex work, Condom negotiations, HIV/AIDS, HIV prevention, Kenya

Palabras clave: HSH, Hombres trabajadores sexuales, Negociación para el uso del condón, VIH, Prevención del VIH, Kenia

RESUMEN

Los hombres trabajadores sexuales (HTS) en Kenia enfrentan una carga desproporcionada de VIH y frecuentemente tienen relaciones sexuales sin condón con sus parejas comerciales. Sin embargo, se sabe poco sobre cómo se llevan a cabo las negociaciones para usar condón entre los HTS y sus clientes. Realizamos entrevistas semiestructuradas con 25 HTS y 11 clientes masculinos de HTS en Mombasa, Kenia, para evaluar las barreras y los facilitadores al uso del condón e investigar los factores que impactan a las negociaciones sobre el uso del condón. Los participantes informaron que las actitudes positivas hacia el uso del condón y perceber el uso del del condón como un comportamiento que promueve la salud facilita el uso del mismo. Barreras para el uso del condón fueron el pago adicional por tener sexo sin condón, la baja percepción del riesgo de VIH/ITS con algunas parejas sexuales, la percepción de menos placer asociado con el uso del condón, el consumo de alcohol y la violencia de parte del cliente contra los HTS fueron barreras para el uso del condón. Las futuras intervenciones deben abordar las barreras a nivel individual y estructural para el uso del condón con el fin de promover una negociación efectiva para el uso del condón en las interacciones entre los HTS y sus clientes.

INTRODUCTION

Male sex workers (MSW), a subpopulation of men who have sex with men (MSM), face a disproportionate burden of HIV. A recent meta-analysis reported a global HIV prevalence of 11.9% in this population, with sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) being the region where MSW have the highest HIV prevalence globally, reaching 36.3% [1]. Previous studies have shown that involvement in sex work is associated with higher HIV prevalence among MSM in Nigeria [2], South Africa [3], Kenya [4], and other regions in the world [5].

High HIV prevalence among MSW in SSA can be attributed to the synergistic effects of behavioral, interpersonal, and structural factors. Behavioral factors include condomless receptive anal sex [2, 3, 6–9], multiple sex partners [4], and alcohol use [6, 10, 11]; interpersonal factors include trust in and perceived attractiveness of sexual partners [10, 12] and violence from sexual partners and the police [3, 10, 13]; and structural factors include socioeconomic disparities [3, 13, 14] and stigma against same-sex practices and sex work [13, 15]. Previous studies with MSW in Kenya [6, 10] reported that engagement in sexual risk behaviors is associated with low levels of knowledge about HIV, use of alcohol and other substances, and trust and intimacy between clients and sex workers. Additionally, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis indicated that HIV prevalence among MSW is higher in countries that criminalize same-sex practices and/or sex work, such as Kenya [15].

Although MSW may have sex with both men and women [7, 14], the majority of their clients are men [10]. Studies in the US [16] and Australia [17] showed high HIV prevalence (6.9% and 8.4%, respectively) among male clients of male sex workers (MCM). There are no studies focusing on the specific barriers to condom use and determinants of HIV risk among MCM in SSA. Additionally, there is a dearth of research on how condom negotiation between MSW and MCM shapes condom use behavior.

Some studies indicate that overt condom negotiation between MSW and MCM facilitates condom use [18, 19], which has prompted interventions to focus on empowering sex workers to overtly negotiate condom use in order to reduce sex work-related HIV risk [20, 21]. Condom negotiation is embedded in the social environments where MSW and MCM interact and is influenced by levels of stigma and discrimination against same-sex practices and sex work and also by access to economic resources [14, 22]. For example, studies show that criminalization of sex work may diminish opportunities for overt condom negotiation in the context of female sex work [23] and contribute to higher HIV prevalence among MSW [15], and that MSW who experienced stigmatization and violence by clients are more likely to engage in condomless sex [24]. Moreover, MSW of low socioeconomic status may face difficulties negotiating condom use with male clients or may accept higher rates for condomless sex [10, 14, 25].

Therefore, paramount to understanding condom use in the context of male sex work is examining the interactions between sex workers and clients and the contexts in which these interactions occur [26]. In the present study, we describe the contexts in which condom use is negotiated and identify barriers and facilitators to condom use between MSW and MCM. We examined the spaces where the interactions and negotiations took place, how MSW and MCM negotiated payment and sex, attitudes toward condom use held by MSW and MCM, and actual experiences with condom use and condomless sex in these encounters.

METHODS

Study setting

The present study took place in Mombasa, Kenya. Mombasa has a general population of over 1.1 million and is the largest city in coastal Kenya [27]. In 2015, HIV prevalence was 7.5% in the adult population in Mombasa (in comparison to 6.3% among adults in the country) [28]. Mombasa is located on the Indian Ocean and along the Trans-African Highway, attracting a large number of tourists and workers in transit through the city [29].

Mombasa’s location makes tourism one of the main economic sectors in the city [27, 29]. Mombasa is also a popular destination for sex tourism and the demand for commercial sex is high [29, 30]. In 2007, a study using the capture-recapture methodology estimated there were 739 MSW in Mombasa [31]. This study also mapped the population of MSW and venues for sex work in the city, identifying 31 bars and nightclubs to be the main locations for male sex work in Mombasa [31, 32]. Data collection for the present study took place in 18 of the 31 bars and clubs previously identified as locations for sex work in Mombasa [31]. The 18 venues were identified to be the main “hotspots” of sex work in the city by sex worker peer educators working with the International Centre for Reproductive Health-Kenya (ICRHK). These bars and clubs were known as places where MSW and female sex workers solicited clients for sex but were also frequented by sex workers for non-sex work-related activities and by individuals not involved in the sex trade.

Study design and participants

The present study was part of a formative research project consisting of 75 semi-structured interviews with male and female sex workers and male clients to inform the development of a multi-level HIV risk-reduction intervention (Project Boresha). The subsequent intervention included peer education and provision of condoms, lubricants, and sexual health services (i.e. HIV and STI testing, counseling, and care) in bars and clubs.

Participants were eligible for the parent formative research study if they met the following criteria: (1) age 18 or older; (2) regular patron of the venue (four visits per month or more); (3) had anal or vaginal intercourse with a sex worker or male client they met at that venue in the past 3 months; (4) visibly sober at that time of the interview, as assessed by a trained interviewer; (5) willing to be audio-recorded; and (6) able to provide consent.

In this analysis, we included all 25 MSW interviewed for the parent study and all 11 MCM who reported having paid for sex with men in the past three months. Our sample included MSW who had sex with both male and female partners and MCM who had sex with both male and female sex workers in the past three months. Fourteen MCM reported only having sex with female sex workers in the past three months and were excluded from the analysis.

Study procedures

Peer educators identified potential participants at the recruitment sites (i.e. bars and club) and referred them to trained interviewers who were also present at the sites. Interviewers then screened potential participants for eligibility in a private location at the bar/club. Eligible individuals were invited to participate in the study and, if interested, completed the informed consent process. Interviewers were trained on how to maintain confidentiality during the study and underwent online training in good clinical practice. Interviewers did not share reasons for eligibility/ineligibility or the content of the interviews with peer educators.

After obtaining informed consent, trained researchers conducted semi-structured interviews in English or Kiswahili, according to participants’ preference, in a private space at the venues or near the venue where participants were recruited. All interviews were audio-recorded. Interviews were conducted between December 2014 and March 2015 (between 3 PM and midnight) and lasted between 60 and 90 minutes.

Assessment domains

Semi-structured interviews addressed varied topics, including sexual identity, the venues where participants went to solicit or provide sex work, strategies for identifying and finding clients/sex workers, negotiations between sex workers and clients, experiences with violence in the context of sex work, condom and lubricant use with sexual partners, knowledge about HIV, HIV and STI risk perception, HIV testing, pre- and post-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP and PEP, respectively), access to preventive services and medical care, strategies for reaching MSW and MCM, and ideas about interventions.

This paper is based on the analysis of MSW’s responses to the following questions: “How do you negotiate the price for sex with a client?” “Have there been times that you felt a client coerced or forced you to do something that you didn’t want to do? Can you tell me about these experiences?” “How do you feel about using condoms with clients?” “How do you think clients feel about using condoms?” and “Can you tell me about times that you do not use condoms with clients?” MSW who had both male and female clients were also asked about how condom use negotiation differed according to client gender.

MCM were asked similar questions: “How do sex workers and clients agree upon the price of sex?” “Have you ever been treated badly by a sex worker? Can you tell me more about this?” “How do you think sex workers feel about using condoms?” “When you have sex with a sex worker, do you prefer to have sex with or without a condom? Could you explain?” and “Can you tell me about times that you did not use condoms with sex workers?” Interviewers were trained to probe all responses for further details and explanations.

Data analysis

Most interviews were conducted in Kiswahili; these interviews were first transcribed into Kiswahili and then translated into English. Three interviews were conducted primarily in English (per participants’ choice), with some responses provided in Kiswahili. These interviews were transcribed in their original language (sections conducted in English were transcribed in English and sections conducted in Kiswahili were transcribed in Kiswahili). The sections in Kiswahili were then translated into English, so that the entire transcript was in English. A researcher at ICRHK fluent in both languages reviewed all transcripts for accuracy.

All coding and data analyses were conducted on the English language transcripts. Members of our research team in Kenya and the U.S. collaborated on the development of a codebook and coding of all transcripts. The process of codebook development and coding is described in detail elsewhere [33]. In short, from May 2015 to April 2016, a team of two masters-level and two doctoral-level researchers developed a comprehensive codebook inductively and deductively and coded all 75 transcripts. Of the 36 interviews with MSW and MCM discussed in this paper, 15 transcripts were double-coded, that is, coded independently by two members of the team, who discussed code application in weekly conference calls with the entire coding team. All differences in coding were discussed and consensus was reached on how to apply codes. This “negotiated agreement approach” is used to ensure consistent interpretation and application of codes, which increases coding reliability [34, 35].

After detailed discussion of these 15 initial transcripts, coders were familiar with the codebook and able to apply codes consistently. The remaining transcripts were coded independently by the coders, but they continued to meet weekly to discuss code interpretations and reflect on emerging themes until all transcripts were coded. We maintained detailed memos describing and reflecting on the coding process, including all instances of divergence in code application. After coding reconciliation, these memos were amended to document decisions made about how to use particular codes. Coding and management of data were conducted in Dedoose Version 6.1.18, a web-based platform for data management and analysis (SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC; Los Angeles, CA).

The present study reports on the thematic analysis of three codes: “negotiating payment/prices with clients/sex workers”, “conflict between sex workers and clients”, and “condom use with clients/sex workers”. We generated code reports containing all excerpts linked to these codes and identified the themes and illustrative quotes contained in these excerpts. After identifying themes, we documented how frequently codes came up by creating a spreadsheet in Microsoft Excel that contained each study participant (rows) and all the themes identified (columns). Counts described in this manuscript refer to the number of participants who mentioned a particular theme, and not the total number of times themes were discussed across all interviews. We assigned each MSW and MCM a sequential numerical identifier to distinguish the different participants who were quoted in this manuscript.

Ethics

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the New York State Psychiatric Institute-Columbia University Irving Medical Center Department of Psychiatry and the Kenyatta Hospital-University of Nairobi Ethics Research Committee. All study participants provided written informed consent. To ensure confidentiality, no personal identifiers were collected.

RESULTS

Our analysis sample consisted of 36 participants: 25 MSW and 11 MCM. MSW ranged in age from 20 to 39 years (M = 26.1 years; SD = 4.3 years) and were on average younger than MCM (age range = 22 – 46 years; M = 32.9 years; SD = 8.5 years). Most participants had at least a high school education, a greater proportion among MCM than MSW (9/11 and 16/25, respectively). Only two MSW were married and five MSW had children, whereas 4/11 of MCM were married and the same number had children. Table 1 presents the socio-demographic characteristics of the sample.

Table 1.

Participants’ socio-demographic characteristics (N = 36)

| MSW (N = 25) | MCM (N = 11) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years (M, SD) | 26.1 (8.54) | 32.9 (4.34) |

| Education (N, %) | ||

| Less than high school | 7 (28%) | 2 (18%) |

| High school | 13 (52%) | 5 (46%) |

| College or more | 3 (12%) | 4 (36%) |

| Missing | 2 (8%) | - |

| Married (N, %) | 2 (8%) | 4 (36%) |

| Children (N, %) | ||

| 0 | 20 (80%) | 7 (64%) |

| 1–2 | 4 (16%) | 3 (27%) |

| 3+ | 1 (4%) | 1 (9%) |

| Anal sex (N, %) | ||

| Any | 25 (100%) | 11 (100%) |

| Insertive only | 1 (4%) | 7 (64%) |

| Receptive only | 9 (36%) | 1 (9%) |

| Both | 15 (60%) | 3 (27%) |

| Recent sex work partners (N, %) | ||

| Men only | 19 (76%) | 7 (64%) |

| Men and women | 6 (24%) | 4 (36%) |

All participants engaged in anal sex in the context of sex work. Among the 11 MCM, seven engaged only in insertive anal sex, one only in receptive anal sex, and three were versatile (i.e. both insertive and receptive anal sex). In contrast, among the 25 MSW, only one engaged exclusively in insertive anal sex, nine exclusively in receptive anal sex, and 15 in both. In the context of sex work, most MSW and MCM only had sex with other men (19/25 and 7/11, respectively). The remainder reported also having commercial sex with women.

Negotiations between male sex workers and male clients

Relationships between sex workers and clients were usually initiated by an overt negotiation of the terms of the sexual exchange. This negotiation process occurred soon after the initial contact at the bars and clubs where MSW and MCM met. Negotiation typically involved direct communication between MSW and MCM, and only rarely were the terms of the sexual exchange (i.e. what kind of sex they would have, where, for how much) defined by other individuals such as club bouncers, other sex workers, or other clients. When asked about how negotiations over the price for the sexual exchange usually started, a MSW explained:

In the clubs, there aren’t a lot of stories, someone just comes up to you and asks, ‘What’s up, short time [quick sexual encounter]?’ You are the one to tell them and someone starts bargaining ‘Eeh 4000 [shillings, or around 40 USD] is a lot, make it 2000’ [around 20 USD]. (MSW-01, 21 years old)

The type of sexual activity expected and the price for the sexual exchange were the main issues negotiated between MSW and MCM. Price was based on characteristics of sex workers and clients, as well as on factors related to the sexual exchange. Most MSW reported charging more from clients they perceived to be wealthy; many also charged extra fees for services such as massage, oral sex, or specific sexual positions. Some MSW charged clients differently according to time of the night and day of the week, month, or year (i.e. higher prices early at night when there were more clients looking for sex, soon after payday, and during the holidays). Interestingly, a few MSW reported charging less money if physically attracted to the client, to the point of occasionally having sex “free of charge” or “for [their] own satisfaction”. Additionally, a few MSW took their own appearance into account when deciding their price for the sexual encounter, charging more money if they had invested more in their own physical presentation (e.g. fancy clothing and make-up).

The amount MCM were willing to spend on sex workers depended, among other factors, on the venue where they met the sex worker (i.e. more money when at high-end bars and clubs), perceived beauty and attractiveness of MSW, and on the package of sexual services they were looking for (e.g. massages, oral sex, caressing, etc., in addition to anal sex). Anal sex was seen as the “standard” sexual practice in these interactions, whereas the other sexual services were “additions” that needed to be negotiated and paid for. When MCM were satisfied with the services provided, they often increased payments to MSW in the form of tips at the end of the encounter.

The majority of MSW (18/25) and MCM (8/11) reported being aware that some MSW in the region would have sex without condoms with clients for additional payment. However, of the participants who were aware of the practice of having condomless sex for higher pay, a few MSW (5/18) and MCM (2/8) reported they had not personally engaged in condomless sex for additional payment. The practice of having condomless sex for higher payment could be initiated by MSW or MCM (i.e. MSW offering clients condomless sex for an extra fee and MCM offering higher payment to persuade MSW to have sex without condoms).

While condom use was discussed many times during the initial negotiation between MSW and MCM and often had a direct impact on the price charged/paid for the sexual exchange, lubricant use did not emerge in negotiations between MSW and MCM and did not affect payment for the sexual exchange.

Condom use in sexual exchanges between male sex workers and clients

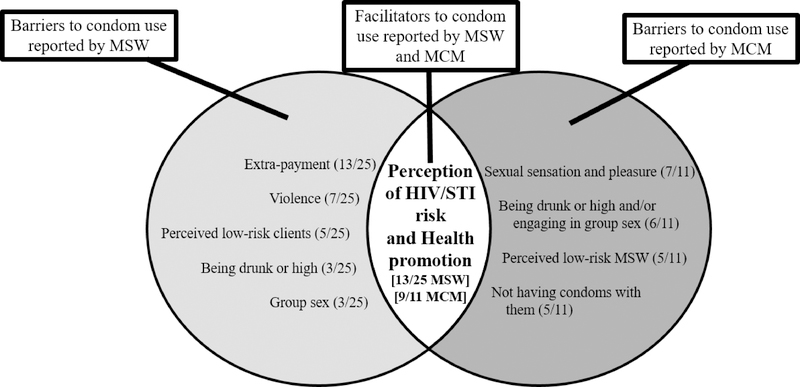

Participants were asked about specific barriers and facilitators to condom use in the context of male sex work. These barriers and facilitators are depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Barriers and facilitators to condom use among MSW and MCM in Mombasa, Kenya.

* Numbers represent how many participants expressed each barrier or facilitator.

Facilitators to condom use

Less than half of the participants who explicitly discussed how often they use condoms reported always using condoms when engaging in male sex work (6/13 MSW and 5/11 MCM). The main facilitator to condom use among MSW and MCM was concern about HIV and other STIs and the perceived health benefits of condom use (13/25 MSW and 9/11 MCM). Understanding condom use as a way to prevent HIV/STIs and promote health facilitated positive personal attitudes toward condom use among the majority of MSW and MCM:

I think they [clients] prefer them [condoms] because everyone loves life and thus would not engage in risky behavior that would endanger it. So I think everyone prefers it [condoms]. (MSW-02, 39 years old)

Sex workers feel that condoms are good and that they protect them from being infected with HIV (…). My view [as a client] is [also] that condoms protect and make us safe. (MCM-01, 31 years old)

Some MSW emphasized that the concern about acquiring an STI would override possible financial gains related to having sex without a condom.

Without a condom the price [for the sexual exchange] will go higher but you are at risk of being infected with diseases. I fear those diseases, [so] it is better to use a condom. If he [the client] does not want to use a condom, I leave him. I fear death. (MSW-03, 28 years old)

Among both groups, being free of HIV/STIs was perceived as a way to maintain their health and allow them to continue working and to support their family and their livelihood:

I want to maintain my business. I don’t want to fall sick because me falling sick means me starving to death because where will I get my money to pay my bills? So using condoms is good for me because it helps me keep healthy and get to my chores and do my work... It really protects me, it protects my work, it protects my clients and, at the end of the day, it is a win-win game. (MSW-04, 23 years old)

For married persons like me, I have to use condoms in every case because of my family, I have to take care. Although other people don’t like them [condoms], we know the risk that is there, so we have to use condoms. (MCM-02, 43 years old)

Some MSW and MCM reported that previous STIs or knowing friends, colleagues, or family who had been diagnosed with HIV increased their concern about HIV and other STIs, thus facilitating condom use.

I really love what I do and [having sex with] condoms. (…) [In the past] I never used to like condoms, I used to have sex without condoms. [Interviewer: And what made you change?] From that day I got infected with gonorrhea. (MSW-05, 26 years old)

I’m very conscious when it comes to condoms because I have seen several sex workers die of AIDS. I have seen some of my family members die of it just because somebody wanted to show off as a boss [by not using condoms] (...) So it’s like the family is not stable, it is destroyed, so I’m very cautious when it comes to condom use. That is number one. (MCM-03, 42 years old)

Barriers to condom use

MSW reported being more likely to have condomless sex with clients with whom they had regular sexual encounters, those perceived to be wealthy, and those who didn’t “look infected”. Clients reported being less likely to use condoms with MSW they perceived to be physically attractive and those they regularly had sex with or with whom they had developed “attachments”. Additionally, clients reported using condoms with MSW they perceived to be “not healthy”:

[Condomless sex with clients] happens, but not frequently…. A client can tell you that he doesn’t want to use a condom. When you ask them why they don’t want, they tell you that they don’t look infected because he has a nice body. The way he speaks and the money he proposes makes me forget and do that act. (MSW-06, 24 years old)

I cannot say I am a “condomizer” [someone who always uses condoms]. I don’t use condoms regularly. [With] people you know, sometimes you get an attachment – I don’t call them relationships, but they are special attachments. You have been with someone for several months and they have never treated you badly, [they have] made sure you get your value for your money [when providing their services]. So this is someone I feel would understand me, this is someone who, if we agree, I would prefer not to have a condom with him if he agrees. And some of them agree and some of them don’t, as much as we have that attachment, that period we have spent together. (MCM-04, 37 years old)

Depending on how [well] I know them [male sex workers], I opt to go with them [have sex] without condoms, [such as] the one [male sex worker] I have sex with every day [often], because with him we are used to each other. (…) [But with other male sex workers], when you look at them you see that they are not healthy and their bodies have infections so you just know that you must use condoms or keep off. (MCM-05, 31 years).

Interestingly, even though most participants reported positive personal attitudes toward condom use, most MSW and MCM perceived the other group to hold negative attitudes toward condoms:

Sometimes you even have to insist on condom use [because] most [clients] do not like using condoms, unless you tell them. (MSW-07, 28 years old)

Most [sex workers] don’t want to use condoms. They usually don’t like it. (MCM-06, 31 years old)

Extra payment for condomless sex was the barrier to condom use most frequently mentioned by MSW (13/25), and many clients (6/11) confirmed that they had offered MSW more money to have sex without condoms. Descriptions of receiving higher pay for condomless sex oscillated between a seemingly consensual and deliberate decision to make more money per sexual act and feeling pressured into the practice due to financial need.

If [sex workers] don’t use condoms, they are paid more so it is upon you to decide if you want that much money without using condoms or you [want to get] a small amount of money and use a condom. The decision is all yours. (MSW-08, 21 years old)

[The client] told me he understood that using condoms was important, but that he was begging me to do it without condom only for that day. I told him it was impossible, but then he mentioned the amount of money he was offering. It was 9,300 shillings [approximately 90 USD]. I lost myself completely and said that that was a lot of money, I could not afford to resist. (MSW-06, 24 years old)

Another MSW reported feeling “forced to accept” condomless sex for the same pay on days he had not been “lucky to find a client”, highlighting the major role of economic vulnerability in condomless sex. In contrast, a MSW who came from a wealthy family explained that he would just “walk away” if a client offered him more money to engage in condomless sex:

As much as I need this money, I cannot jeopardize my health... I don’t come from a family that is desperate; my parents are wealthy, my granddad is a senior government official, so if at all I lacked anything, I would go back to them. (MSW-09, 27 years old)

The discussion of whether to accept higher pay for condomless sex was usually part of the negotiation between MSW and MCM that happened before sex, but one MSW also described his strategies to make clients pay more after having sex without condoms:

I do expect more [money for condomless sex] because even after [condomless] sex, I do pretend to have been injured so that he may sympathize with me and add me [give me more] money. (MSW-06, 24 years old)

Some MSW (7/25) also reported that MCM imposed condomless sex without sex workers’ consent, for instance, by removing condoms without the knowledge of the sex worker, overtly refusing to use condoms, or forcing MSW to have sex without condoms. Nonconsensual condomless sex usually resulted in unilateral deviations from the terms of the negotiation by clients. In these instances, MSW and MCM had agreed on using condoms during the initial negotiation at the bars and clubs where they met, but when they reached the venues where they had sex, clients insisted on not using condoms.

We had agreed [on using condoms], then after [at the room where they would have sex] he tells you he does not want to use a condom, he says, “If I have to wear a condom then I am leaving.” So I had to do it [have sex without a condom]. (MSW-10, 23 years old)

Episodes of nonconsensual condomless sex described by MSW ranged from “giving in to the client’s demands” in hopes of “maintaining the client” and not “pissing him off” to physical intimidation and rape:

There is [a male client] who forced me … He fucked me without a condom and his money was less and he wanted by force and looking at him he looked like he could destroy you. I had to [do it] because where I was I couldn’t do anything, looking at the place it was risky, it was in the ghetto so if you refuse you don’t know what he might do, so you have to agree. (MSW-11, 28 years old)

Another MSW described an episode in which a peer (i.e. another MSW) was gang raped: The first person who approached you [the victim], tells you that he [the perpetrator] will use condoms, but when the other ones [additional perpetrators] come, you find that some will wear but some will not wear [condoms]. Maybe they are used to raping people, they just have sex like that. One finishes, then the next has sex with you, then they leave you there and go their way. (MSW-12, 25 years old)

Unlike MSW, no MCM reported having been pressured by sex workers into having sex without condoms. The majority of MCM (7/11) reported that condoms interfered with pleasure during the sexual act and that decreased pleasure was a barrier to condom use. However, most of these clients indicated that sex workers, and not they themselves, were the ones who complained about less pleasure when using condoms. The negative impact of condoms on sexual pleasure drove clients’ perception that MSW held negative attitudes toward using condoms. MCM reported that, in some situations, decreased pleasure was associated with MSW feeling pain related to condom use, sometimes leading MSW to intentionally burst condoms (e.g. by tearing the tip of the condoms) or remove the condom during intercourse without the knowledge of clients.

Many [sex workers] don’t like condoms. They say that they feel like they are burning with condoms, then they don’t feel the pleasure. In fact, if you are not very careful, you can put on a condom and the [sex worker] will remove it. Then if you don’t care, you can find that you have had sex without a condom. (MCM-02, 43 years old)

Similarly, 5/11 MCM emphasized the importance of having their own condoms with them as a way to prevent condomless sex and MSW tampering with the condoms. No MSW mentioned their own pleasure as a barrier to condom use.

Some clients and sex workers also reported that group sex was associated with not using condoms. Sex workers and clients highlighted that group sex commonly followed alcohol use, contributing to improper use of condoms or not using condoms at all.

All those years I have been here, I came to experience and I came to discover that in group sex, condoms are not there. They [the people who engage in group sex] usually don’t have that time. (MSW-13, 24 years old)

[During group sex] alcohol is usually used because some people say they must be ‘steamed’ [drunk] to be able to [have group sex] (…) Most of the time condoms are not used and when it is used, it is not used properly. (MSW-08, 21 years old)

Sometimes [condom use] is rare in that kind of thing [group sex] because nobody is planning to have sex at that time. It’s like we are celebrating, it’s like we are having fun, it’s like all of a sudden everyone is drunk. (MCM-03, 42 years old)

Alcohol use, whether in the context of group sex or not, contributed to condomless sex by making individuals less strict about condom use, not using condoms correctly, and failing to notice condom slippages during the sexual act:

Alcohol use makes your consciousness not as alert as possible so you’re probably not as strict on your protection as always. So [you might not wear the condom properly] but you may not even take notice… Or [like] in my case [the condom] might burst and you continue with it [sex]. (MCM-07, 26 years old)

Although participants were asked about condomless sex while using drugs, none reported engaging in this practice.

Condom use between male sex workers and female clients

Six MSW reported having both male and female clients, but most explained that the majority of their clients were men and that only occasionally would female clients engage their services. MSW perceived the risk of HIV transmission to differ between anal and vaginal sex: three MSW perceived vaginal sex to pose greater risk of HIV transmission, two perceived anal sex to pose greater risks, and one did not know. Despite different perceptions of risk, no MSW reported selectively having condomless sex with only female clients or only with MCM. Similar to interactions with male clients, MSW reported that female clients offered higher pay for condomless sex and that trust in female clients also facilitated condomless sex:

[There is a female client who] told me that she does not want to use condoms because when she uses condoms, she feels like she is being inserted with a stick and she wants the real sweetness [real pleasure related to sex]. (…) So I was forced not to use condoms [Interviewer: Then she paid you more?] Yes, with that she has to pay more. (MSW-14, 26 years old)

Vaginal [sex with a female client] you can do even without condom provided you have someone you trust and you also trust yourself [not to have HIV/STIs]. (MSW-15, 26 years old)

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate condom negotiation and use by focusing on the perspectives and experiences of both MSW and MCM in SSA. Examining similarities and differences in the perspectives of the two groups allows us to better understand the factors that result in condom use or non-use in these interactions. Our study thus contributes to a growing literature on male sex work and sheds light on the importance of also simultaneously studying clients of sex workers in order to understand the context and determinants of condom use in these interactions.

Most participants in our study, both MSW and MCM, reported positive attitudes toward condoms and mentioned condom use as a health-promoting behavior. This contrasts with Okal et al. who reported a decade ago that condomless sex was “normative” among MSW in Mombasa, Kenya [10]. Though our purposive, non-representative sample does not allow for determining social norms among all MSW in Mombasa, the discrepancy between our findings with those of Okal and colleagues might indicate that norms related to condom use among MSW in the region have changed. Future research should examine social norms related to condom use in a larger, representative sample of MSW and clients in the region to determine the current norms and attitudes toward condom use and how, if at all, they have been affected by public health interventions in the region.

Our findings also indicate that positive attitudes toward using condoms do not necessarily translate into actual use of condoms. Whereas the majority of participants understood that condom use promotes health and prevents HIV/STIs, the perception that some sexual encounters present low HIV and STI risk likely contributes to infrequent condom use. Participants reported being less likely to use condoms with partners they perceived not to be infected with HIV or another STI. Perceived wealth, beauty, and physical appearance were some of the aspects considered to determine condom use or non-use. Additionally, having repeated sexual encounters with the same commercial sex partner also facilitated condomless sex. These findings reinforce the extensive literature that links trust, “healthy” appearance, and regular commercial sex partnerships as facilitators to condomless sex in the context of male sex work in many different settings [10, 12, 22, 25, 36, 37].

Our study indicates that condom use is the outcome of ongoing interactions between sex workers and clients, and that condom negotiation is a process that begins when MSW and MCM meet and agree on price and continues until they actually have sex. A key moment in the interactions between sex worker and client is the overt negotiation of payment, type of sexual activity, and condom use, which usually occurred soon after MSW and clients met. As part of the negotiation process, MSW reported that male and female clients offered MSW extra payment to have sex without condoms, a phenomenon that has been described in other studies with male and female sex workers [10, 13, 25, 37–40]. Previous research has interpreted this practice as a “risk premium”, which assumes MSW to be rational agents employing a personal financial strategy in response to economic incentives to have condomless sex [13, 41]. However, our study shows that while MSW may have some agency (e.g. when they negotiate directly with clients regarding payment, type of sexual activity, and condom use and when they choose to have condomless sex to make more money), not all MSW freely chose to engage in condomless sex, but instead were being pressured into the practice. This pressure stemmed predominately from financial need, with MSW feeling forced to comply with clients’ demands to have condomless sex in order to maintain their livelihood.

It is important to emphasize that agreeing to use condoms at the beginning of the negotiation process did not guarantee that condoms were actually used. Condom negotiation between MSW and MCM was a tentative process, which is illustrated by clients changing what had been previously agreed upon with sex workers and imposing condomless sex. In these instances, the imposition of condomless sex by clients was achieved through threats, physical aggression, and rape of MSW, thereby unilaterally breaking the terms of the agreement negotiated with sex workers.

Nonconsensual or violence-related condomless sex is of particular concern because it is not subject to negotiation between sex worker and client and is thus beyond sex workers’ personal volition. As described by Okal et al. in their study with MSW in Kenya, condom use in the context of nonconsensual or coercive sex is “only feasible if the perpetrator [opts] for protection” (p. 816) [10], which is often not the case. Moreover, rather than just interpersonal violence, these instances of coercion should be seen within the context of Kenya’s high level of structural stigma (heterosexism and stigma against sex work) [15] and socioeconomic inequality, which also hinder condom use. Therefore, although participants had positive attitudes toward condom use and MSW had some agency to negotiate condom use before the sexual exchange, this negotiation was not always effective and did not ensure actual condom use. We identified economic vulnerability and direct coercion from clients to be important constraints to MSW’s ability to enforce condom use, which may contribute to the increased HIV risk in this population.

Previous studies have described that, in addition to direct violence from clients [24], other forms of violence, such as violence from intimate partners and law enforcement agents [10, 13, 24], may also contribute to condomless sex and HIV vulnerability among MSW. However, these types of violence did not emerge as barriers to condom use in our study and we did not specifically probe about condom use in sexual interactions with law enforcement agents. Future studies should examine the extent to which violence from clients, intimate partners, the police, and other perpetrators contribute to condomless sex and HIV risk among MSW and MCM in Kenya.

Even though participants were not specifically asked about the effect of condoms on pleasure during sex, decreased sexual sensation associated with condoms emerged from interviews with MCM as a barrier to condom use. This is aligned with previous studies that have described discomfort and reduced pleasure as being associated with condomless sex in the context of male sex work in SSA [10, 12]. Interestingly, however, MCM reported that it was not their own pleasure, but that of sex workers’, that made them forego using condoms. In our study, MSW reported having sex for free or charging lower prices from clients they found attractive, suggesting that pleasure contributes to their engagement in sex work. This is in line with a study with MSW in Mombasa that showed that men may sell sex for varied reasons, including to access same-sex love and pleasure [10]. However, no MSW in our study described pleasure as a reason to have condomless sex, suggesting that the role this factor plays in determining condom use may be limited.

There are a number of possible explanations for the discrepancy between responses of sex workers and clients regarding sexual pleasure and condomless sex. First, it is possible that clients may be attributing condomless sex, a behavior seen as “unhealthy”, to sex workers because of their awareness of the association between condoms and STI/HIV prevention. This form of projection (i.e. attribution of undesirable behaviors to other individuals or groups to sustain the understanding of oneself as “healthy” while others are “unhealthy” or deviant) was described early in the HIV epidemic and is commonly employed against stigmatized groups, such as sex workers [42]. Clients may also be attributing responsibility for condomless sex to sex workers due to social desirability bias. Furthermore, previous research indicates that sex workers may “suss out” clients’ needs and desires with the objective of acting and presenting themselves in ways that maximize their own financial gains [19, 43]. For instance, we found that clients’ level of attraction to a sex worker and satisfaction after the sexual exchange increased the price paid for the sexual encounter. Therefore, we speculate that MSW may be acting as though having pleasure-driven sex so as to capitalize on clients’ presumed desire for sex motivated by pleasure. This strategy could eventually lead MCM to think that the sex worker’s pleasure is the reason for condomless sex, when in fact it is mainly about the higher pay related to not using condoms. Although we did not examine specific strategies sex workers employ to maximize their financial gains in our interviews, one MSW did report pretending to be in pain after condomless sex to deliberately manipulate clients and obtain extra money by appealing to clients’ “sympathy”. Future research should explore what, if any, strategies MSW in coastal Kenya employ to maximize their earnings and what is the impact of these strategies on condom use.

Finally, we identified alcohol use to be an important barrier to condom use, consistent with previous studies with MSW in Kenya [6, 10, 11] and elsewhere [12, 37, 44]. We also identified an association between group sex, alcohol use, and condomless sex. Similar findings are described in the qualitative study by Vu et al. with MSM and MSW in Vietnam, which showed a link between drug use and condomless group sex [45]. Future research is needed to elucidate the nuances of condom negotiation in the context of group sex, the extent of alcohol use and group sex among MSW in Kenya, and their impact on condom use and HIV risk. Such studies will provide the grounds for interventions to address HIV/STI risk in the context of group sex, as well as initiatives to mitigate the negative effects of alcohol and substance abuse on the health of sex workers and their clients in Kenya.

Limitations

Our findings must be interpreted in light of the limitations of this study. First, considering the inherently personal nature of the questions and topic of the interviews, social desirability bias in the responses cannot be completely ruled out. This could have been the case when, for example, MSW and MCM reported positive attitudes toward condom use and when MCM attributed responsibility for condomless sex to MSW’s desire for sexual pleasure. With that in mind, however, we formulated questions using open-ended and non-judgmental phrasing and asked similar questions in different ways so as to elicit candid responses. Moreover, by examining both MSW and MCM perspectives, we were able to triangulate our sources and increase the validity of our findings [46].

Second, since we recruited participants from bars and nightclubs, our findings may not be generalizable to the population of MSW and MCM in Mombasa who go to other venues for sex work (e.g. beaches, brothels, mobile phones, dating websites). For example, alcohol use may not be as an important barrier to using condoms correctly among MSW and MCM who do not engage in commercial sex in bars, clubs, and other venues where alcohol consumption is common. Our recruitment strategy was based on a comprehensive mapping of the population of sex workers in Mombasa [31, 32] and aimed to reflect the most important venues for sex work in the region at that time. Moreover, conducting interviews with participants at the venues where they actually go to buy/sell sex may provide opportunities for participants to express richer and more realistic accounts of the context and setting of interactions between MSW and MCM [47].

Third, considering that most MSW in our study only had sex with male clients, our description of condom use in interactions between MSW and female clients is limited. Further research should examine how, if at all, MSW’s sexual practices and condom negotiation strategies differ in interactions with male and female clients.

Finally, we emphasize that the present study is part of a comprehensive formative research study to inform a multi-level HIV prevention intervention targeting male and female sex workers and their clients. As such, in-depth interviews addressed a wide range of topics and were not limited to discussions about condom use negotiation. Given our broad focus, semi-structured interviews were not able to explore all possible factors influencing condom use negotiation that have been described in other studies. For example, our interviews did not address how awareness of and previous experiences with PrEP and PEP might influence condom negotiations and actual condom use (a detailed description of participants’ perspectives on PrEP and PEP, can be found in Restar et al. [48]). Rather than an exhaustive description of condom use barriers and facilitators among MSW and MCM in Mombasa, Kenya, we analyze how condom negotiation took place in our sample and describe main factors affecting condom use in these interactions.

Despite the limitations, we believe this study makes an important contribution to the literature, especially considering the dearth of studies focused on condom negotiations and other interactions between MSW and MCM in SSA. Future research should continue to elucidate factors that could influence condom negotiation in these relationships, such as violence from intimate partners and the police, and how condom negotiation differs across different venues for sex work (e.g. online and offline) [49].

Implications

In light of the incentives not to use condoms, such as making more money and perceived greater pleasure, it is probably unrealistic to assume that individual-level messages promoting condoms alone will be able to bring about large-scale behavior change [40]. Other possible behavioral change strategies include providing financial incentives to MSW in order to overcome “risk premiums” related to condomless sex [50], and microfinance programs, which have been shown to increase condom use among female sex workers in Kenya [51].

Moreover, given violence from clients was a barrier to condom use, public health interventions should also target clients, who often are in a position of power in relation to sex workers, hence in greater control of condom use during commercial sexual exchanges. Structural interventions that address multi-level stigma, violence, and decriminalization of sex work and same-sex practices may be particularly important in this context [14, 15]. Among female sex workers, interventions to promote community empowerment and reduce sex worker-related stigma have led to increases in condom use and decrease in new HIV infections among female sex workers [20, 52, 53]. Likewise, initiatives to curb condomless sex in the context of male sex work should empower sex workers and facilitate effective condom negotiation by creating environments conducive to effective condom negotiation [20, 21]. In our study, condom negotiation between MSW and clients began at the bars and clubs frequented for sex work, indicating that future interventions should consider targeted HIV prevention initiatives in these venues. For example, previous studies have shown that venue-based testing in bars and other venues that sell alcohol may improve the detection of new cases of HIV and STIs among MSM [54] and promote condom use among female sex workers [55]. In that sense, interventions that include management and employees of these venues and peer educators may be particularly promising [56] and future research should evaluate the feasibility of such interventions among MSW and MCM in Kenya.

CONCLUSION

Our study sheds light on key characteristics of male sex work in coastal Kenya and elucidates barriers and facilitators to condom use and negotiation, increasing the understanding of HIV risk among MSW in a region of high HIV prevalence in Kenya [28]. An extensive body of research has indicated that condomless sex is common in female sex work and appears to be closely related to multi-level stigma, disempowerment, and criminalization of sex work, contributing to increased HIV risk in this population [23]. Research with female sex workers has prompted the implementation of interventions to address structural factors that rely on existing social networks, empowerment, and provision of institutional support for this population [20, 52, 57, 58]. Such interventions may have contributed to a substantial reduction of the HIV burden among female sex workers in Kenya and elsewhere [23, 57, 58]. Unfortunately, research and interventions addressing sexual health and HIV prevention needs of MSW are much scarcer. We believe that interventions with female sex workers provide important lessons about addressing structural determinants of condomless sex and should guide future interventions directed to improve the health of MSW and their clients in SSA and globally.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the study participants for their time and input and the International Centre for Reproductive Health-Kenya (ICRH-K) for their support. We would also like to thank Alberto Edeza for translation of the abstract into Spanish.

This research and manuscript preparation was supported by a National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) grant, NIMH 5R01MH103034 (Principal Investigator: Joanne E. Mantell: A Structural Intervention for Most-At-Risk Populations in Mombasa, Kenya), and a NIMH Center Grant P30-MH43520 (Principal Investigator: Robert H. Remien, Ph.D). NIMH had no role in the conceptual and writing of this manuscript. This manuscript does not reflect the official views of NIMH.

Footnotes

This manuscript has not been published previously (partly or in full), nor is it being considered for publication elsewhere.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

REFERENCES

- 1.Oldenburg CE, Perez-Brumer AG, Reisner SL, Mattie J, Bärnighausen T, Mayer KH, et al. Global burden of HIV among men who engage in transactional sex: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE. 2014;9(7):e103549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vu L, Adebajo S, Tun W, Sheehy M, Karlyn A, Njab J, et al. High HIV prevalence among men who have sex with men in Nigeria: implications for combination prevention. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2013;63(2):221–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baral S, Burrell E, Scheibe A, Brown B, Beyrer C, Bekker L-G. HIV risk and associations of HIV infection among men who have sex with men in peri-urban Cape Town, South Africa. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muraguri N, Tun W, Okal J, Broz D, Raymond HF, Kellogg T, et al. HIV and STI prevalence and risk factors among male sex workers and other men who have sex with men in Nairobi, Kenya. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2015;68(1):91–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oldenburg CE, Perez-Brumer AG, Reisner SL, Mimiaga MJ. Transactional sex and the HIV epidemic among men who have sex with men (MSM): results from a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS and Behavior. 2015;19(12):2177–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geibel S, Luchters S, King’ola N, Esu-Williams E, Rinyiru A, Tun W. Factors associated with self-reported unprotected anal sex among male sex workers in Mombasa, Kenya. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2008;35(8):746–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mannava P, Geibel S, King’ola N, Temmerman M, Luchters S. Male sex workers who sell sex to men also engage in anal intercourse with women: evidence from Mombasa, Kenya. PLOS ONE. 2013;8(1):e52547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geibel S, King’ola N, Temmerman M, Luchters S. The impact of peer outreach on HIV knowledge and prevention behaviours of male sex workers in Mombasa, Kenya. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2012;88(5):357–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baral S, Trapence G, Motimedi F, Umar E, Iipinge S, Dausab F, et al. HIV prevalence, risks for HIV Infection, and human rights among men who have sex with men (MSM) in Malawi, Namibia, and Botswana. PLOS ONE. 2009;4(3):e4997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okal J, Luchters S, Geibel S, Chersich MF, Lango D, Temmerman M. Social context, sexual risk perceptions and stigma: HIV vulnerability among male sex workers in Mombasa, Kenya. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2009;11(8):811–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luchters S, Geibel S, Syengo M, Lango D, King’ola N, Temmerman M, et al. Use of AUDIT, and measures of drinking frequency and patterns to detect associations between alcohol and sexual behaviour in male sex workers in Kenya. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Musinguzi G, Bastiaens H, Matovu JKB, Nuwaha F, Mujisha G, Kiguli J, et al. Barriers to condom use among high risk men who have sex with men in Uganda: a qualitative study. PLOS ONE. 2015;10(7):e0132297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okanlawon K, Adebowale AS, Titilayo A. Sexual hazards, life experiences and social circumstances among male sex workers in Nigeria. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2013;15(sup1):22–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baral SD, Friedman MR, Geibel S, Rebe K, Bozhinov B, Diouf D, et al. Male sex workers: practices, contexts, and vulnerabilities for HIV acquisition and transmission. Lancet (London, England). 2015;385(9964):260–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oldenburg CE, Perez-Brumer AG, Reisner SL, Mayer KH, Mimiaga MJ, Hatzenbuehler ML, et al. Human rights protections and HIV prevalence among MSM who sell sex: cross-country comparisons from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Global Public Health. 2018;13(4):414–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grov C, Wolff M, Smith MD, Koken J, Parsons JT. Male clients of male escorts: satisfaction, sexual behavior, and demographic characteristics. The Journal of Sex Research. 2014;51(7):827–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prestage G, Jin F, Bavinton B, Hurley M. Sex workers and their clients among Australian gay and bisexual Men. AIDS and Behavior. 2014;18(7):1293–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bloor MJ, Barnard MA, Finlay A, McKeganey NP. HIV-related risk practices among Glasgow male prostitutes: reframing concepts of risk behavior. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 1993;7(2):152–69. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Browne J, Minichiello V. The social meanings behind male sex work: implications for sexual interactions. British Journal of Sociology. 1995;46:598–622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jana S, Basu I, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Newman PA. The Sonagachi Project: a sustainable community intervention program. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2004;16(5):405–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lippman SA, Donini A, Díaz J, Chinaglia M, Reingold A, Kerrigan D. Social-environmental factors and protective sexual behavior among sex workers: the Encontros intervention in Brazil. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(S1):S216–S23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mimiaga MJ, Reisner SL, Closson EF, Perry N, Perkovich B, Nguyen T, et al. Self-perceived HIV risk and the use of risk reduction strategies among men who engage in transactional sex with other men in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. AIDS Care. 2013;25(8):1039–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shannon K, Strathdee SA, Goldenberg SM, Duff P, Mwangi P, Rusakova M, et al. Global epidemiology of HIV among female sex workers: influence of structural determinants. The Lancet. 2015;385(9962):55–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.George PE, Bayer AM, Garcia PJ, Perez-Lu JE, Burke JG, Coates TJ, et al. Is intimate partner and client violence associated with condomless anal intercourse and HIV among male sex workers in Lima, Peru? AIDS and Behavior. 2016;20(9):2078–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McKinnon LR, Gakii G, Juno JA, Izulla P, Munyao J, Ireri N, et al. High HIV risk in a cohort of male sex workers from Nairobi, Kenya. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2014;90(3):237–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Waldo CR, Coates TJ. Multiple levels of analysis and intervention in HIV prevention science: exemplars and directions for new research. AIDS (London, England). 2000;14:S18–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. Mombasa county statistical abstract. Nairobi, Kenya: Kenya National Bureau of Statistics; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kenya National AIDS Control Council. Kenya AIDS response progress report 2016. Kenya National AIDS Control Council; Nairobi, Kenya: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hampanda KM. The social dynamics of selling sex in Mombasa, Kenya: a qualitative study contextualizing high risk sexual behaviour. African Journal of Reproductive Health / La Revue Africaine de la Santé Reproductive. 2013;17(2):141–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kibicho W Tourism and the sex trade in Kenya’s coastal region. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 2005;13(3):256–80. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Geibel S, van der Elst EM, King’ola N, Luchters S, Davies A, Getambu EM, et al. ‘Are you on the market?’: a capture–recapture enumeration of men who sell sex to men in and around Mombasa, Kenya. AIDS (London, England). 2007;21(10):1349–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Geibel S Same-sex sexual behavior of men in Kenya: implications for HIV prevention, programs, and policy. Facts, Views & Vision in ObGyn. 2012;4(4):285–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Masvawure TB, Mantell JE, Tocco JU, Gichangi P, Restar A, Chabeda SV, et al. Intentional and unintentional condom breakage and slippage in the sexual interactions of female and male sex workers and clients in Mombasa, Kenya. AIDS and Behavior. 2018;22(2):637–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Campbell JL, Quincy C, Osserman J, Pedersen OK. Coding in-depth semistructured interviews: problems of unitization and intercoder reliability and agreement. Sociological Methods & Research. 2013;42(3):294–320. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garrison DR, Cleveland-Innes M, Koole M, Kappelman J. Revisiting methodological issues in transcript analysis: negotiated coding and reliability. The Internet and Higher Education. 2006;9(1):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Padilla M, Castellanos D, Guilamo-Ramos V, Reyes AM, Marte LES, Soriano MA. Stigma, social inequality, and HIV risk disclosure among Dominican male sex workers. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67(3):380–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kong TS. Risk factors affecting condom use among male sex workers who serve men in China: a qualitative study. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2008;84(6):444–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ford K, Wirawan DN, Fajans P, Thorpe L. AIDS knowledge, risk behaviors, and factors related to condom use among male commercial sex workers and male tourist clients in Bali, Indonesia. AIDS (London, England). 1995;9(7):751–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shah M Do sex workers respond to disease? Evidence from the male market for sex. American Economic Review. 2013;103(3):445–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karim QA, Karim SS, Soldan K, Zondi M. Reducing the risk of HIV infection among South African sex workers: socioeconomic and gender barriers. American Journal of Public Health. 1995;85(11):1521–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Belza MJ, Llacer A, Mora R, Morales M, Castilla J, Fuente Ldl. Sociodemographic characteristics and HIV risk behaviour patterns of male sex workers in Madrid, Spain. AIDS Care. 2001;13(5):677–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Crawford R The boundaries of the self and the unhealthy other: reflections on health, culture and AIDS. Social Science & Medicine. 1994;38(10):1347–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sanders T ‘It’s just acting’: sex workers’ strategies for capitalizing on sexuality. Gender, Work & Organization. 2005;12(4):319–42. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Biello KB, Colby D, Closson E, Mimiaga MJ. The syndemic condition of psychosocial problems and HIV risk among male sex workers in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. AIDS and Behavior. 2014;18(7):1264–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vu BN, Mulvey KP, Baldwin S, Nguyen ST. HIV risk among drug-using men who have sex with men, men selling sex, and transgender individuals in Vietnam. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2012;14(2):167–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Patton MQ. Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health Services Research. 1999;34(5 Pt 2):1189. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Elwood SA, Martin DG. “Placing” interviews: location and scales of power in qualitative research. The Professional Geographer. 2000;52(4):649–57. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Restar AJ, Tocco JU, Mantell JE, Lafort Y, Gichangi P, Masvawure TB, et al. Perspectives on HIV pre- and post-exposure prophylaxes (PrEP and PEP) among female and male sex workers in Mombasa, Kenya: implications for integrating biomedical prevention into sexual health services. AIDS Education and Prevention: Official Publication of the International Society for AIDS Education. 2017;29(2):141–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mimiaga MJ, Reisner SL, Tinsley JP, Mayer KH, Safren SA. Street workers and internet escorts: contextual and psychosocial factors surrounding HIV risk behavior among men who engage in sex work with other men. Journal of Urban Health. 2009;86(1):54–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Galárraga O, Sosa-Rubí SG, González A, Badial-Hernández F, Conde-Glez CJ, Juárez-Figueroa L, et al. The disproportionate burden of HIV and STIs among male sex workers in Mexico City and the rationale for economic incentives to reduce risks. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2014;17(1):19218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Odek WO, Busza J, Morris CN, Cleland J, Ngugi EN, Ferguson AG. Effects of micro-enterprise services on HIV risk behaviour among female sex workers in Kenya’s urban slums. AIDS and Behavior. 2009;13(3):449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kerrigan DL, Fonner VA, Stromdahl S, Kennedy CE. Community empowerment among female sex workers is an effective HIV prevention intervention: a systematic review of the peer-reviewed evidence from low- and middle-income countries. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17(6):1926–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kerrigan D, Kennedy CE, Morgan-Thomas R, Reza-Paul S, Mwangi P, Win KT, et al. A community empowerment approach to the HIV response among sex workers: effectiveness, challenges, and considerations for implementation and scale-up. The Lancet. 2015;385(9963):172–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Allan-Blitz L-T, Herrera MC, Calvo GM, Vargas SK, Caceres CF, Klausner JD, et al. Venue-based HIV-testing: an effective screening strategy for high-risk populations in Lima, Peru. AIDS and Behavior. 2019;23(4):813–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kalichman SC. Social and structural HIV prevention in alcohol-serving establishments: review of international interventions across populations. Alcohol Research & Health: the Journal of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. 2010;33(3):184–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Morisky DE, Stein JA, Chiao C, Ksobiech K, Malow R. Impact of a social influence intervention on condom use and sexually transmitted infections among establishment-based female sex workers in the Philippines: a multilevel analysis. Health Psychology. 2006;25(5):595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kerrigan DL, Fonner VA, Stromdahl S, Kennedy CE. Community empowerment among female sex workers is an effective HIV prevention intervention: a systematic review of the peer-reviewed evidence from low- and middle-income countries. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17(6):1926–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Reza-Paul S, Lorway R, O’Brien N, Lazarus L, Jain J, Bhagya M, et al. Sex worker-led structural interventions in India: a case study on addressing violence in HIV prevention through the Ashodaya Samithi collective in Mysore. The Indian Journal of Medical Research. 2012;135(1):98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]