Abstract

DNA nanostructures have emerged as promising novel drug and gene delivery systems. Sophisticated programmable hybrid DNA nanotherapeutics have also been used for controlled and targeted drug and gene delivery. There are also numerous reports of utilizing DNA aptamers as nanomaterials targeting moieties. However, the body of literature on these DNA-based nanotherapeutics is fragmented and is not systematically reviewed. The purpose of this review is to systematically summarize the design strategy for various oligonucleotide-based programmable nanotherapeutics that are responsive to biomolecules.

Keywords: Aptamer, DNA origami, oligonucleotide nanotherapeutic, programmability

Teaser:

A systematic review on how to design different programmable nanotherapeutics using oligonucleotides as building blocks or as surface and matrix modifiers for controlled and targeted delivery of various therapeutic agents in presented.

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Over the past three decades a variety of nanomaterials made of polymeric [1–4] lipids [5] and organic and inorganic compounds [6] have been investigated as novel and alternative drug delivery systems. The architectures of these nanomaterials include nanoparticles [1–6], liposomes [7,8], nanocrystals [9], micelles [10], nanoemulsions [11,12], polymersomes [13], dendrimers [14–16], nanogels [17,18], nanofibers [19], nanowires [20], nanorods [21], nanoscaffolds [22], nanopatterned surfaces [23], nanocomposites [24], nanofluidic devices [25], carbon nanotubes [26], nanosheets [27] and nanomembranes [28]. These nanocarriers have improved drug solubility, stability, permeability and release [29–32]. Some of them have also been designed to be responsive to physical and chemical stimuli for targeted and more-efficient biological effects, which has been recently systematically reviewed by our group [33,34]. In parallel to physical- and chemical-responsive nanotherapeutics, biological stimuli-responsive nanotherapeutics made of DNA or RNA have emerged as attractive and important smart systems for biological applications owing to the unique genetic information, easy synthesis and sequence-specific binding behavior of DNA [35]. DNA encodes, stores and transfers nearly all the biological information necessary for life [36,37]. It contains two complementary, long-strand DNA chains that are joined by specific base-pairing interactions: adenine (A) and thymine (T); guanine (G) and cytosine (C), to intertwine around a common axis and form a double-stranded helix [38]. The double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) helix also folds to assume different polymorphic forms depending on the DNA sequence, the presence of ligands and the surrounding environment [39]. Mostly, DNA–ligand interactions are sequence specific, which is also a fundamental process of life. Different proteins bind selectively to only one, or just a few, specific DNA sequence(s) out of the millions present in a genome [40]. For instance, the antiviral antibiotics netropsin and distamycin selectively bind to AT-rich sequences in the minor groove of DNA [41]. Similarly, the neuronal DNA/RNA-binding protein Pur-alpha binds to single- and double-stranded nucleic acids that contain nucleotide bases GG and A, G, C or T (GGA, GGG, GGC or GGT) to regulate replication, transcription and translation, playing a crucial part in postnatal brain development [40]. Such interactions are mainly via H-bonding but van der Waals and electrostatic interactions are also often involved [40]. The understanding of the binding modes and sequence-specific binding behavior of DNA led to the development [35] of DNA-based nanostructures as biosensor chips [42], templates to align α-helical membrane proteins during protein structural determination by NMR [43], templates for the construction of plasmonic structures for concentrating, guiding and switching light in nanoscale devices [44] and drug and gene delivery devices [45], among others. Oligonucleotides and aptamers (specific DNA sequences that interact with various cells and other biological macromolecules) have also been utilized to modify the surfaces of organic and inorganic nanomaterials to improve their cellular uptake and targeting potential [35]. Despite safety risks and social and ethical implications, genes have also been investigated as therapeutic agents for the treatment of some severe diseases such as spinal muscular atrophy and hemophilia B. Recently, the FDA has received >700 new investigational drug applications for gene therapies and three products have already been approved, including axicabtagene ciloleucel for the treatment of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, tisagenlecleucel for certain patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and young adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia and voretigene neparvovecrzyl for patients who have an inherited retinal disease caused by mutations in both copies of the RPE65 gene and have enough remaining healthy cells in the retina. However, gene therapy is not within the scope of this review [46]. Here, we systematically review the strategies of designing pure and hybrid self-assembled random DNA nanostructures as well as oligonucleotide- and aptamer-modified nanocarriers for controlled delivery and release of small and large drug molecules and genes. We also discuss how these design strategies can help to overcome the current limitations and improve the outcomes of therapy.

Programmable DNA nanomaterials

Self-assembled DNA nanostructures

Design principles and strategies of self-assembled DNA nanostructures.

Recently, self-assembled DNA nanostructures have been investigated as promising gene and drug (mainly biomacromolecules and small drug molecules that resemble deoxyribonucleosides) delivery devices. However, effective gene delivery is difficult to achieve because of naked nucleic acid inherent susceptibility to enzymatic degradation in the biological milieu, rapid excretion from the body owing to their relatively low molecular weights and poor cell permeability owing to their net negative charge [47–50]. To mitigate these challenges, four major strategies have been devised. The first strategy is to synthesize DNA analogs that can resist enzymatic degradation but synthetic oligonucleotide analogs can exhibit unpredictable off-target effects and preclude advantageous interactions with their targets [47,51]. The second strategy is to PEGylate therapeutic nucleic acids and, as a matter of fact, a PEGylated 28-mer aptamer PEG–aptanib was approved by the FDA for the treatment of age-related macular degeneration of the retina [48]. The third strategy is to use various viral and nonviral nanocarriers such as cationic liposomes and cationic transfection agents. However, the application of these nanocarriers is hampered by their toxicity, immunogenicity, rapid DNA release and nucleic acid instability [50,51]. The fourth strategy is to use self-assembled DNA nanostructures, which can be ‘DNA-brick self-assemblies’ or ‘DNA origamis’ [47–50].

DNA-brick self-assemblies are rigid, well-defined and sophisticated 3D nanostructures like polyhedra (e.g., tetrahedra, octahedra, dodecahedra and icosahedra), buckyballs, nanotubes, nanocages, and prepared by assembly of carefully designed short synthetic single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) motifs (tiles) [36,38,52,53]. Such nanostructures (Figure 1a) have been utilized as synthetic hosts to encapsulate various biomacromolecules like antigens and proteins (Table 1) that are difficult to be encapsulated in other nanocarriers owing to their large size and sensitive nature [54]. They have also been used to increase the cellular uptake of nonfunctionalized and noninteracting macromolecules through endocytic pathways. For example, Bhatia et al. [54] encapsulated a 10 kDa fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-dextran in a synthetic icosahedral DNA to form an icosahedral DNA host–cargo complex. Unlike free FITC-dextran, the FITC-dextran encapsulated in the DNA cargo was exclusively taken up by Drosophila hemocytes through receptor-mediated endocytosis. Small therapeutic agents that resemble deoxyribonucleosides can also be copolymerized to the DNA tiles and assembled into DNA nanostructures. For example, Mou et al. [53] phosphorylated the anticancer agent floxuridine, which is structurally similar to thymine, and used it in place of thymine to form DNA strands. The DNA strands were then self-assembled into tetrahedron, dodecahedron and buckyball nanostructures. The three DNA nanostructures showed floxuridine-loading capacities of 17.94%, 18.36% and 18.36%; and enhanced the uptake of the floxuridine by HeLa cells more than five, seven and ninefold, respectively.

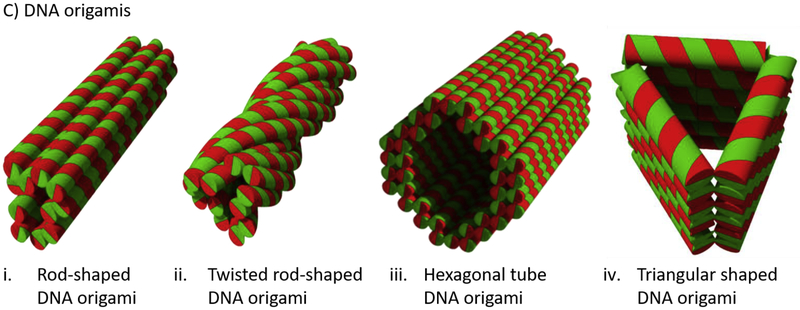

Figure 1.

Schematic representations of (a) DNA-brick self-assembly nanostructures designed as gene and drug delivery devices, (b) a 2D tile (an origami blueprint) formed by 27 short strand staple DNAs using the open source (MIT license) Cadnano 2 software and a 3D rectangular DNA origami obtained by hybridization of an M13mp18 DNA scaffold with the 27 short strand staple DNAs and (c) selected DNA origamis (red: scaffold DNA; green: staple DNAs) investigated as gene and drug delivery devices.

Table 1.

Summary of different DNA-brick self-assemblies and DNA origamis designed for therapeutic oligonucleotides and drug delivery

| Design | No. | Nanostructure | Compound(s) loaded | Purpose/application | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA-brick self-assemblies | 1. | DNA tetrahedron (self-assembeled from 4 ssDNAs) (Figure 1ai) | Antigen, streptavidin (STV) and adjuvant, cytosine-phosphate-guanine oligodeoxynucleotide (CpG-ODN) complex that resembles a natural viral particle | Induced a strong and long-lasting antibody response against the antigen: two immunizations of the STV-CpG-ODN-complex-loaded tetrahedron developed ~2-fold higher anti-STV IgGs in BALB/c mice than the free STV-CpG ODN complex in 70 days | [45] |

| Horse-heart holo-cytochrome C, a 2.4 kDa protein, which was conjugated to the 5′ end of one of the ssDNAs before assembly | Protein incarceration was dependent on the conjugation site of the protein on the oligonucleotide. Binding the protein to the center of one of the tetrahedral arms enabled encapsulation of the protein, whereas the protein projected outside when conjugated at or close to the edges | [100] | |||

| Doxorubicin (intercalate into DNA duplexes) | Reversed drug resistance in doxorubicin-resistant (MCF-7/ADR) breast cancer cell line, possibly by reducing p-GP efflux. Unlike the free doxorubicin (viability ≈ 90% at 0.1 μM), the same amount of doxorubicin loaded in the DNA tetrahedron was cytotoxic (viability ≈ 60%) to the cells | [101] | |||

| Methylene blue, a photosensitizer that can potentially be used for photodynamic therapy of tumor | Peritumoral administration of the methylene-blue-loaded tetrahedron, along with laser exposure, suppresses the growth of SCC7-cell-induced subcutaneous tumor xenograft in mice over 16 days. By contrast, the tumor volume increased 14 and 16 times in groups treated with free methylene and the control group, respectively | [102] | |||

| 2. | DNA icosahedron (assembled from 15 DNA sequences). It was telomerase (an enzyme that is expressed in 85–90% of human cancer cells but almost absent in normal cells) responsive (Figure 1aiii) | Platinum nanoparticles | In tumorous cells telomerase digested the DNA icosahedron causing the loaded platinum ions to be discharged and enter into the nucleus to induce DNA damage and cell death. In cisplatin-resistance BCG823/DDP tumor-bearing nude mice, 90% of the animals treated with platinum-nanoparticle-loaded icosahedral survived for 30 days in comparison to the 60, 20 and 10% survival rate for the groups treated with the free platinum nanoparticles, cisplatin and the control group, respectively | [33] | |

| 3. | Shuriken-shaped DNA nanostructure | MicroRNA-145 (it is downregulated in most cancer cell lines and tissue and reinstating miR-145 could immediately suppress tumor growth and block cell invasion and metastasis). It was conjugated to the DNA star motif by hybridization | The uptake of the mRNA by colorectal cancer cell line (DLD-1) was 30- and 2-fold higher than the free mRNA and mRNA loaded in Lipofectamine™ 2000 (a common transfection agent), respectively. In addition, the proliferation of the cells treated with the mRNA-conjugated DNA-Shuriken, the free mRNA, the unloaded DNA star motif and the negative control over 24 h was 46.3%, 85.9%, 81.2% and 77.8%, respectively | [103] | |

| 4. | DNA nanotubes (Figure 1aiv) | - | Unlike double-stranded DNA, the nanotubes were resistant to nuclease degradation and could enter into the human cervical cancer (HeLa) cells | [35] | |

| DNA origamis | 1. | Triangular DNA origami (Figure 1civ) | Doxorubicin (intercalates into DNA duplexes) | Intravenous injection of free doxorubicin and the doxorubicin-loaded triangular origami every 3 days for 12 days (dose = 4 mg/kg doxorubicin) to tumor-bearing mice reduced the tumor growth to about 1/2 and 1/3, respectively. In addition, the weight of the tumor-bearing mice treated with the free doxorubicin decreased significantly but not in those mice treated with the doxorubicin-loaded origami | [57] |

| Carbazole derivative photosensitizer (for photodynamic therapy of cancer) | Taken up by regular human breast adenocarcinoma cancer (MCF-7) cells. Upon near infrared irradiation, MCF-7 cells treated with free photosensitizer and the photosensitizer-loaded origami started apoptosis in 480 and 300 s, respectively | [59] | |||

| 2. | Rectangular DNA origami nanosheet (90 nm × 60 nm × 2 nm) | RNase A: for cancer therapy. Conjugated with a random sequence DNA and hybridized on the origami with capture strands | The rectangular DNA origami significantly enhanced the cellular uptake of RNase A in MCF-7 cells and inhibited their growth in a concentration-dependent manner (cell viability decreased from ~80% to ~20% when the RNase A level increased from 1 to 8 μg/ml). The native RNase A did not inhibit tumor cells growth at the concentrations investigated | [60] | |

| 3. | Rod-shaped DNA origami Trojan horse (~92.5 × 13.2 × 11 nm) | Daunorubicin (intercalates into DNA duplexes) | Increased intracellular daunorubicin concentration by 40% in HL-60/ADR multidrug-resistant human leukemia cells lines by increasing the cellular uptake and minimizing the efflux pump-mediated drug efflux and enhanced the cytotoxic effect of the drug | [58] | |

| 4. | Hexagonal tube DNA origami (Figure 1ciii). It has three biotinylated binding sites on its inner surface to bind with avidin-modified cargo | Streptavidin-modified lucia luciferase enzymes | Fluorescent measurements showed that the DNA origami enhanced the permeability of the enzymes threefold in HEK293 cells in vitro. The enzymes also stayed intact and retained their activity in the transfection process | [62] | |

| 5. | Oc tahedron RNA origami (edge length ≈ 12 nm). Formed by annealing part of a 30-UTR of a Renilla luciferase reporter gene with nine staple strands | The scaffold RNA contains intrinsic substrates for Dicer to produce siRNAs | The octahedron silenced expression of the Renilla luciferase reporter gene in H1299 cells similar to an optimized siRNA control | [61] |

Despite the advantages and promises of the DNA nanostructures discussed, it is Paul Rothemund’s [55] invention of DNA origami that launched a new era of DNA nanotechnology. DNA origamis are usually formed by self-assembly of a long viral-genome-derived ssDNA (a scaffold) into a well-defined DNA nanostructure with the help of multiple ssDNA strands (staple strands). The staple strands are hybridized to selected domains of the DNA scaffold to give the desired 2D or 3D nanostructure [36]. These nanostructures are designed or programmed in silico into the desired shape and size by using DNA design software, which applies the basic principles of Watson–Crick base-pairing and the helical geometry of dsDNA, becoming computer-aided programmable smart nanomaterials [56]. For example, M13mp18 DNA scaffold can be assembled into rectangular DNA origami in two steps (Figure 1b). In the first step, a 2D tile (the blueprint) that allows choice of various lengths of staples (27 short-stranded staple DNAs in Figure 1b) is designed using Cadnano 2 software. In the second step, the M13mp18 DNA scaffold is hybridized with staple DNAs to obtain a 3D rectangular DNA origami using Maya 2015 software. Experimentally, a DNA nanostructure can be obtained by mixing a DNA scaffold with staple DNA strands, rapidly heating to up to 90°C and then slowly cooling to room temperature to allow the staple strands to pull the long scaffold strands into the designed or programmed nanostructure. The staple strands are designed in such a way that they only hybridize with the DNA scaffold and not with each other. As a result, the relative stoichiometric ratio of staple strands and DNA scaffold should not be strictly controlled to get a high yield [36]. Accordingly, various DNA origamis have been designed (Figure 1c) and used to load different small and macromolecular drugs such as doxorubicin [57,58] and carbazole derivative photosensitizer [59] daunorubicin [58], RNase A [60] or siRNAs [61] (Table 1). The DNA origamis significantly enhanced the cellular uptake, membrane permeability and the pharmacologic effect, minimized the side effects and improved the stability of the loaded drugs [57–62]. The release of drugs from DNA origamis can be achieved by degradation of the DNA origami by the body’s DNAse or through administration of short complimentary DNA sequences (triggering sequences) that hybridize with staple strands to cause hybridization-triggered phase transition of the DNA origami [52,56,63,64]. The drug release can also be controlled by using external stimuli such as DNA, mRNA, proteins, enzymes or pH to change conformation or reconfigure the assembly networks of the DNA origami [56].

Characteristics of self-assembled DNA nanostructures.

The important characteristics of self-assembled DNA nanostructures is that their drug-loading capacity, biodistribution and cellular uptake strongly depend on their shape, size, geometry and valence. For example, Bastings et al. [65] folded a long, 7308-nucleotide, 5000 kDa DNA scaffold into a thin rod (7 nm × 400 nm), a thick rod (15 nm × 100 nm), a ring (140 nm outer diameter), a barrel (60 nm outer diameter), an octahedron (50 nm longest axis) and a block (16 nm × 21 nm × 50 nm) and investigated the uptake of the different shaped nanostructures by bone-marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs). Their results showed that the uptake of the compact block nanostructure by the BMDCs was 15-times greater than the parent dsDNA. Among the different nanostructures, the uptake decreased linearly with increasing the degree of compactness (block > barrel > octahedron > thick rod > ring > thin rod), owing to the decrease of the accessible surface-area:volume ratio and increasing the compactness. Similarly, to investigate the effect of size, they folded a short, 3024-nucleotide, 2000 kDa scaffold into thin rod (7 nm × 170 nm), thick rod (15 nm × 40 nm) and a ring (60 nm outer diameter) and found that the uptake of larger nanostructures by BMDCs was higher than that of smaller nanostructures owing to different uptake mechanisms. Caveolae-mediated uptake predominantly facilitated the uptake of nanoparticles up to 500 nm, whereas clathrin-mediated endocytosis was mainly involved in the uptake of particles <200 nm. In another study, Mou et al. [53] showed that the uptake of dodecahedron and buckyball DNA nanostructures by HeLa cells were ~1.5- and 2-times greater than that of a tetrahedron DNA nanostructure. Jiang et al. reported that the doxorubicin loading capacity of a free M13mp18 DNA scaffold and the corresponding 2D triangular and 3D tubular origamis was ~30%, 50% and 60%, respectively, after 24 h of incubation [66]. The uptake of the three systems by MCF 7 cells was 79.5, 192.4 and 218.9, respectively, measured by flow cytometry. In addition, bright-field and fluorescence microscopy investigations showed that the 3D tubular origami was less toxic than the 2D triangular origami in doxorubicin-resistant MCF 7 cells; unlike the free doxorubicin and doxorubicin-loaded dsDNA, the origami-bound doxorubicin induced cell death. Similarly, Zhao et al. [67] designed doxorubicin-loaded straight (138 nm long and 13 nm diameter) and twisted DNA nanotubes (Figure 1ci and 1cii) and showed that the straight nanotubes had 33% more doxorubicin-loading capacity than the twisted DNA nanotubes but released the loaded doxorubicin almost as fast as the necked dsDNA (>80% released in 2 h). By contrast, the twisted nanotubes released the loaded doxorubicin slowly and it took 10 h to release ~80% of the drug. In addition, the straight nanotube released doxorubicin following Fickian diffusion kinetics, whereas the twisted nanotube released doxorubicin following non-Fickian diffusion kinetics. Furthermore, confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) investigations showed that the twisted nanotubes slowly released doxorubicin in three different breast cancer cell lines (i.e., MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-468 and MCF-7) and was less toxic but more apoptotic to the cells than free doxorubicin. Zhang et al. [57] investigated the biodistribution of triangular (59.0 nm), tube (80.9 nm) and square (98.6 nm) DNA origamis formed from a circular single-stranded M13 DNA after intravenous tail injection of the origamis to subcutaneous tumor-bearing mice. Quantum dots were loaded in the nanostructures to track the nanostructures in the body. Fluorescence imaging of the quantum dots demonstrated that the triangular DNA origami mainly accumulated in the tumor site with maximum accumulation was achieved within 6 h of injection and remained higher for 24 h, whereas the square and tube DNA origamis were mainly distributed in liver and kidney. By contrast, free quantum dots and quantum dots loaded on Ml3 DNA were not detectable indicating complete clearance from the body 24 h post injection.

DNA nanoparticles are generally considered as nontoxic and biodegradable because they are of purely biological origin [68–70]. Short DNA molecules are also nonimmunogenic [69]. However, studies indicated that a high amount of DNA nanoparticles might cause unintended priming of the immune system because the excessive extracellular RNA or DNA might mimic the condition of high viral and bacterial DNA accumulation that occurs during infection [64,71]. DNA nanoparticles, unlike ssDNAs and dsDNAs that undergo spontaneous hydrolysis and nuclease-mediated digestion in the body, are relatively stable in cell lysates and remain intact in the body for a relatively longer period of time [68–70]. For example, the DNA tetrahedron remained intact for at least 4 h in 50% non-inactivated fetal bovine serum but its parent ssDNA degraded within 2 h [68]. 2D origami nanostructures (90 × 60 nm rectangular or 30 nm equal-sided triangle structures) and 3D DNA origami nanostructures (8 helix by 8 helix square lattice with dimensions of 16 × 16 × 30 nm multilayer rectangular parallelepiped structures) were found to be stable in DNA lysates obtained from a normal metaplastic human esophageal epithelial cell line or End1/E6E7, MCF-10A, cancerous HeLa or MDA-MB-231 cancer cells for 12 h at 4°C and room temperature. By contrast, the corresponding ssDNAs and dsDNAs (M13 mp18 viral DNAs) degraded within 1 h [72]. When human β-actin gene (40 bases long) was conjugated to a rectangular origami as a capture probe the gene remained stable for at least 12 h upon incubation with HeLa cell lysate. Although DNA nanostructures are less susceptible to lysate degradation, they still degrade by exonucleases and endonucleases [64]. To enhance the stability of DNA nanostructures, the 3′ and 5′ ends of the oligonucleotides can be conjugated with PEG; locked nucleic acids and peptide nucleic acid can be used; nucleic acid analogs with modified chirality such as l-DNA can be used; the 2′-OH group on the ribose of RNA nucleotides can be replaced with 2′-fluoro or 2′-O-methyl groups [64,71].

Modification of self-assembled DNA nanostructures to enhance programmability.

To improve tissue targeting, permeability and cell transfection of DNA nanostructures, aptamers (see detailed discussions below), cell targeting molecules like folic acid, cell-penetrating peptides and antibodies have been conjugated to the DNA nanostructures [62]. For example, Lee et al. [73] showed that after small interfering RNA (siRNA)-loaded DNA tetrahedron was conjugated to folic acid the efficiency of the siRNA in reducing luciferase expression in HeLa cells increased by >50%. The folic-acid-conjugated tetrahedron primarily accumulated in tumor and kidney, with little accumulation in other organs such as liver, spleen, lung and heart, after tail-vein injection to nude mice bearing KB (a subline of the cervical adenocarcinoma HeLa cells) xenograft tumors. The blood circulation half-life of the siRNA loaded in the DNA tetrahedron was four-times longer than siRNA alone (~24.2 min vs ~6 min). Similarly, Ko et al. [69] developed 50–200 nm diameter thick and 40 μm long DNA nanotubes by self-assembly of 52-base ssDNA strands (5′-CCA AGC TTG GAC TTC AGG CCT GAA GTG GTC ATT CGA ATG ACC TGA GCG CTC A-3′). They conjugated 0, 5, 10 and 20% of the DNAs with folate and 45% of the DNAs with fluorescent dye Cy3 via N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) chemistry. Confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) images showed that the DNA nanotubes could be taken up by human nasopharyngeal epidermal carcinoma cells. The uptake increased linearly with increasing percentage of folate-conjugated DNAs and increased fourfold when 10% folate-conjugated DNAs were used but stopped increasing when >10% folate-conjugated DNAs were used owing to saturation of the folate receptors. In another study, conjugation of a tumor-penetrating functional peptide specific to neuropilin-1 receptor to doxorubicin-loaded DNA tetrahedron by a click reaction enhanced the endocytosis of the tetrahedron in intracranial human primary glioblastoma cells by ~40% [74]. Similarly, Setyawati et al. [75] conjugated cetuximab – a monoclonal antibody that specifically targets epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) – to the three vertices of a doxorubicin-loaded DNA tetrahedron through sulfosuccinimidyl-4-[N-maleimidomethyl]cyclohexane-1-carboxylate crosslinking and assessed the cellular uptake and the tumor-targeting potential of the DNA nanostructure. The antibody conjugation increased the uptake of the tetrahedron in EGFR-overexpressing MDA-MB-468 breast cancer cells 2.5-fold. By contrast, antibody conjugation did not improve tetrahedron uptake in non-EGFRs expressing normal NIH 3T3 fibroblasts. In addition, the IC50 (50% inhibition concentration) of doxorubicin in the EGFR-overexpressing breast cancer cells decreased to 56% (1.36 vs 3.06 μM) and 70% (0.91 vs 3.06 μM) when it is loaded in DNA tetrahedron and cetuximab-conjugated DNA tetrahedron, respectively. By contrast, the IC50S of doxorubicin, the doxorubicin-loaded DNA tetrahedron and the antibody-conjugated doxorubicin-loaded DNA tetrahedron in the non-EGFR-expressing normal fibroblasts (NIH 3T3) were 2.067, 1.17 and 4.51 μM, respectively.

DNA nanomaterials can also be modified with a wide variety of biomolecules to trigger cellular mechanisms like the immune response. For example, Schiiller et al. [76] designed hollow-tube-shaped DNA origamis composed of different anchor sequences ~80 nm in length and ~20 nm in diameter using an 8634-nucleotide ssDNA scaffold and 227 staple strands (Figure 2). The tube had 62 inner and outer binding sites for cytosine-phosphate-guanine oligodeoxynucleotide (CpG-ODN), an immunostimulatory therapeutic oligodeoxynucleotide that binds to endosomal Toll-like receptor (TLR)9 and initiates release of cytokines and expression of surface molecules that stimulate and boost the immune system. The CpG-ODN-decorated DNA origami nanotubes induced the TLR9-mediated immune response more efficiently than the free CpG-ODN in freshly isolated mouse splenic dendritic cells, evidenced by a high interleukin (IL)-6 production and an up to fivefold increase in the transmembrane C-type lectin CD69 expression – an early marker of immune activation. Similarly, Li et al. [68] assembled four CpG-ODN-bearing 55-mer DNA strands by conjugating the CpG-ODN sequence to the end of DNA tetrahedron with a 7-mer oligothymine spacer in between. Their CLSM investigations showed that the DNA tetrahedron increased the cellular uptake of CpG-ODN in RAW264.7 cells (a cell line established from Abelson murine leukemia virus induced tumor) by about threefold and increased the production of cytokines tumor necrois factor (TNF)α, IL-6 and IL-12 at least ninefold compared with the ssDNAs. Moreover, unlike the classic nanoparticles, DNA nanoparticles can also form anisotropic functionalized nanomaterials (only part of the surface functionalized) owing to their sequence programmability, distinctive molecular ability and facile chemical modification features [77].

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of CpG-ODN-modified tube-shaped DNA origami. Conjugation of nonmodified and partially or fully phosphorothioate (PTO)-modified phosphate backbone CpG-ODN to tube-shaped DNA origami and tcellular uptake with subsequent cytokine and surface molecules production. 1. Endocytotic internalization of the DNA origami; 2. vesicle segregation by the Golgi apparatus containing the transmembrane Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9); 3. fusion of endosomes with the DNA origami and TLR9 containing vesicle; 4. recognition of CpG-ODN sequence by TLR9 and starting of signaling cascade; 5. expression of surface molecules and release of cytokines that stimulate immune response. Figure reproduced, with permission, from [76].

Hybrid self-assembled DNA nanostructures

Design principles and strategy of self-assembled hybrid DNA vesicles.

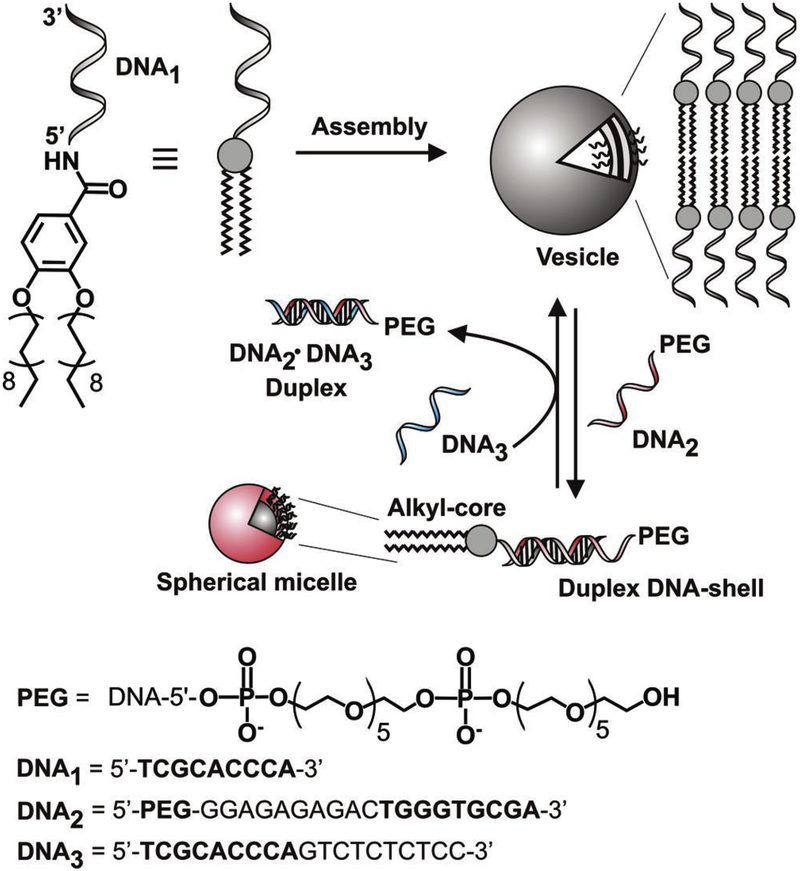

Oligonucleotides can be conjugated with hydrophobic polymers or lipids to form discreet amphiphilic molecules, which can self-assemble into unique micelles [78,79] and liposomal nanostructures [52] to improve the permeability and stability of various therapeutic agents. Different chemistries such as 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC)/NHS reaction [78], HATU coupling [47] and copper-free click chemistry [79] have been used to conjugate oligonucleotides with polymers or lipids of interest [51]. The structural features of the these supramolecular nanostructures can be altered by dehybridization of the DNA strands or biodegradation of the block copolymers, enabling programmable delivery of therapeutic genes, antisense oligodeoxynucleotides (oligodeoxynucleotides that block the expression of specific proteins by hybridization with target mRNA sequences), siRNA or other therapeutic agents [51,78]. For example, Jeong and Park [78] chemically conjugated a 10 kDa hydrophobic poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) polymer to a hydrophilic 4.6 kDa antisense c-myc oligonucleotide (CACGTTGAGGGGCAT) to form an amphiphilic block copolymer that self-assembled into ~80 nm micelles in aqueous solution. The hybrid micelles significantly increased the uptake of c-myc oligonucleotide by fibroblast cells (<0.1% vs 68.3%). Furthermore, the micelles slowly released the oligonucleotide for >50 days following burst-free zero-order release kinetics. Similarly, Rush et al. [51] conjugated a hydrophobic carboxylic-acid-terminated norbornyl polymer to an antisense locked nucleic acid through an amide linkage to form an amphiphilic diblock copolymer that self-assembled in aqueous solution into 20 nm spherical micelles with a polynorbornyl core. The micelles increased the uptake of the nucleic acid by HeLa cells more than tenfold. In addition, the micelles significantly depleted survivin mRNA levels in the HeLa cells. Zhang et al. [79] conjugated the terminal segment of an azide-modified polycaprolactone with cyclooctyne-terminated antisense DNA strands via copper-free click chemistry to form an amphiphilic DNA-brush block copolymer that self-assembled into ~40 nm spherical micelles. The formation of the brush border enabled high DNA loading (302 strands per micelle) compared with micelles formed using the block copolymer of the DNA strand and polycaprolactone (190 strands per particle). In addition, the permeability of the brush-block-copolymer-based micelles in HeLa cells was almost twofold higher than the linear-block-copolymer-based micelles. Quantification of EGFP protein expression also showed that the former micelles were more effective at regulating gene expression via the antisense mechanism than the latter. In another study, Thompson et al. [52] conjugated the 5′-termini of a 9-mer ssDNA with 3,4-di(octadecyloxy)benzoic acid (a lipid with two 18-carbon alkyl hydrophobic tails) to form an amphiphilic compound, which spontaneously assembled into 500 nm unilamellar liposomes (Figure 3). Upon addition of a complementary DNA strand conjugated to PEG, the liposomes underwent phase transition and turned into smaller (20–25 nm) micelles. The vesicle-to-micelle phase transitions could be reversed when a third complementary ssDNA was added to interact with the DNA of the PEG-complementary DNA strand conjugate. Formation of self-assembled DNA nanostructures also minimized oligonucleotide digestion by endonucleases and exonucleases. For example, Rush et al. [47] conjugated a hydrophobic polymer with a ssDNA (5′-TTTAGAG-TF-CATGTCCAGTCAG-TD-G; where TF and TD are thymine bases to which fluorescein dye and DABCYL, respectively, were attached for FRET analysis) to form a DNA–polymer amphiphile that self-assembled into 20 nm micelles. The ssDNA had a substrate (5′…CCA…3′) between fluorescein and DABCYL-labeled thymidine moieties for nicking the endonuclease Nt.CviPII [a nicking endonuclease that recognizes dsDNAs and introduces a single strand break on the 5′ side of the recognition site (5′…*CCX…30, where X = A, G or T)]. In the presence of the nicking endonuclease, the free ssDNA was degraded but the DNA–polymer micelles were not affected by the enzyme. The same degradation pattern was also observed when switching the fluorescein and DABCYL-labeled thymine bases and when the naked DNAs and the micelles were exposed to exonuclease III and snake-venom phosphodiesterase.

Figure 3.

Self-assembly of DNA–lipid conjugates into big spherical unilamellar vesicles that undergo phase transition into smaller spherical micelles in a fully reversible fashion via DNA hybridization (+ DNA2) and strand invasion (+ DNA3) cycles. Figure reproduced, with permission, from [52].

Modification of self-assembled hybrid DNA vesicles.

The surfaces of DNA-polymer hybrid nanoaggregates can be modified by hybridization with another complementary DNA sequence that is conjugated with an appropriate targeting moiety to enhance their targeting potentials. For example, Alemdaroglu et al. [80] designed doxorubicin-loaded 10.8 ±2.2 nm DNA (5′-CCTCGCTCTGCTAATCCTGTTA-3′) polypropylene oxide copolymer micelles and introduced folic acid to their surfaces via hybridization of the micelles with a complementary DNA strand that was conjugated with folic acid. Surface functionalization of the micelles increased their uptake by Caco-2 cells based on the number of folic acid molecules attached to their surfaces. Two targeting folic acid molecules per micelle did not significantly improve cellular uptake of the micelles but 28 folic acid molecules per micelle increased the uptake tenfold.

Oligonucleotide sequences as nanocarrier surface and matrix modifiers

We have discussed the design principles and strategies of self-assembled DNA as a core of nanostructures for therapeutic applications. Here, we will discuss how oligonucleotides are used as surface or matrix modifiers to the core made of non-DNA or non-oligonucleotide materials of nanostructures for therapeutic applications.

Oligonucleotides as nanocarrier surface modifiers.

When oligonucleotide sequences are used to functionalize the surface of polymeric [81] and inorganic [50] nanoparticles (Figure 4a) and nanostructured vesicles (Figure 4b) they can improve the cellular uptake and thermodynamic stability of the nanoparticles and vesicles [81,82]. Spherical nucleic acid nanoparticles (SNAs) (Figure 4a) – nanocarriers that contain a linear, densely packed and highly oriented nucleic acid shell – are the most investigated of these groups of nanocarriers [83,84]. Unlike linear nucleic acids, SNAs can cross the negatively charged cell membrane and enter cells without the need for cationic transfection agents [50,83,84]. As a result, they have often been used as permeation enhancers to increase the cellular uptakes of nanoparticles [83,85]. For example, Giljohann et al. showed that the uptake of random DNA-functionalized gold nanoparticles by A549 cells was 103-times greater than their oligo-ethylene-glycol-functionalized counterparts [82]. In another example, Banga et al. [85] functionalized the surfaces of 30 nm unilamellar liposomes using a 30 nucleic acid base DNA strand conjugated to a hydrophobic tocopherol group that intercalated into the phospholipid layer of the liposomes via hydrophobic interaction. CLSM investigation showed that the liposomal SNAs readily entered ovarian adenocarcinoma (SKOV-3) cells in high quantities after 1 h of incubation. By contrast, the free DNA was not taken up by the cells even after 36 h of incubation under identical conditions. Similarly, anti-human epidermal growth factor receptor (HER)2 oligonucleotide-functionalized liposomal SNAs reduced the HER2 protein levels in SKOV-3 cells by 85% using the housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) as an internal reference for the protein quantification.

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of various hybrid nanoparticles prepared by surface modification of different nanotherapeutics using oligonucleotides ( = DNA,

= DNA,  = aptamer).

= aptamer).

Hollow SNAs are further developments on SNAs and are formed by dissolving the cores of conventional SNAs (Figure 4c). Apart from improved cell permeability, these SNAs are less toxic than the regular SNAs because they do not contain a potentially toxic organic core and the empty core can be utilized to load biologically active compounds [85]. For example, anti-eGFP DNA-oligonucleotide-functionalized hollow SiO2 nanoparticles were synthesized by oxidative dissolution of their gold core using I2. The resulting hollow nanoparticles were internalized by mouse endothelial carcinoma (C166) cells without the need for ancillary transfection agents. In addition, unlike the scrambled nontargeting-DNA-functionalized hollow and gold-core SNAs, the anti-eGFP DNA-functionalized hollow and gold-core SNAs decreased the eGFP mRNA levels by 68% and 50%, respectively [83]. Apart from SNAs, other sophisticated nanocarriers with oligonucleotide surfaces have also been designed. For example, Shen et al. [77] successfully synthesized nanosized DNA origami clamps of defined shape and size with hinges in which they encapsulated gold nanorods (Figure 5). To induce effective and precise encapsulation, the surfaces of the gold nanorods were decorated by DNA sequences that were complementary to the DNA sequences protruding out of the inner surfaces of the clamp. They also added projecting DNA strands on the outer surface of the clamps that served as anchors to other nanoparticles to which complementary DNA strands were attached. This enabled site-selective functionalization of gold nanorods.

Figure 5.

Schematic illustration of functionalization of gold nanorods with DNA origami clamps. (a) The gold nanorods were first modified with thiolated ssDNA. The ssDNA-gold nanorod was then encapsulated by the DNA clamp through DNA hybridization with the capture and complementary strands inside the clamp. (b) Further strands outside the clamp formed specific recognition sites for other gold nanoparticles that were modified with complementary ssDNA. Figure reproduced, with permission, from [77].

According to a few reports, SNAs and other oligonucleotide surface-functionalized nanocarriers undergo a class A scavenger receptor-mediated cell binding and caveolin-1-mediated endocytosis [50,82]. In support of this, Choi et al. [50] showed that SNA uptake by human keratinocyte cells (HaCaT) was 4.8-fold higher than their uptake by human lung adenocarcinoma epithelium (A549) cells owing to the significantly higher level of class A scavenger receptors and caveolin-1 expression in the HaCaT cells. In C166 and mouse fibroblast (3T3) cells, cells that express an intermediate levels of class A scavenger receptors and caveolin-1, SNA uptake was intermediate [50]. Similarly, Giljohann et al. [82] showed that the uptake of random DNA-functionalized gold nanoparticles by HeLa cells was about threefold and 30-fold higher than their uptake by C166 and A594 cells, which correlated well with the level of class A scavenger receptors and caveolin-1 expression by the cells. The cellular uptake of SNAs is also dependent on the density of oligonucleotides on the nanocarrier surfaces [50,82]. Higher oligonucleotide density can lead to higher amounts of protein adsorbed on the nanocarrier surfaces, stronger interaction of the nanocarriers with scavenger receptors and greater nanoparticle endocytosis. For example, Giljohann et al. [82] noticed the uptake of low-density-oligonucleotide-containing ethyleneglycol-coated gold nanoparticles by C166 cells was insignificant when the oligonucleotide density was low but the SNA uptake increased to ~1.3 × 106 per cell when the oligonucleotide density was increased to 60 strands per nanocarrier. However, a further increase in oligonucleotide strand density did not increase the SNA uptake by the cells. Another issue with cellular uptake of SNAs is their specificity. SNAs are taken by healthy and diseased cells indiscriminately. To avoid this universal cell entry mechanism, various cell-targeting moieties, like antibodies and aptamers, can be attached to the SNAs to guide them to specific cell types [84]. For example, conjugation of a HER2 monoclonal antibody to gold nanoparticle core SNAs increased their uptake by ovarian cancer SKOV-3 cells 7.8- and 10.1-fold at 37 and 4°C, respectively [84]. Besides the capability of increasing the cellular uptake of nanoparticles, SNAs can improve the thermodynamic stability of polymeric nanoparticles owing to the electrostatic repulsion between the negative charges of the oligonucleotides on the shell of the nanoparticles [50]. SNAs can also be indirectly used to protect nucleic acids from enzymatic degradation. For example, Seferos et al. [86] functionalized the surfaces of 13 ±1 nm diameter gold nanoparticles using thiol-modified 20-base ssDNA oligonucleotides [5′-CCCAGCCTTCCAGCTCCTTG-(A)10-propylthiol-3′] to make DNA-gold SNPs and then hybridized the ssDNAs using fluorescein-labeled DNA complements (5′-CAAGGAGCTGGAAGGCTGGG-fluorescein-3′). When they increased the amount of ssDNA conjugated on the gold nanoparticles from 6 ±1 to 10 ±1 and to 12 ±1 pmol/cm2 the degradation half-life of the DNA increased 2.1-, 2.9- and 4.2-fold, respectively, in the presence of deoxyribonuclease I.

Oligonucleotides as crosslinkers and matrix modifiers.

When oligonucleotides are incorporated in the matrices of polymeric nanocarriers they can improve the loading efficiency of drugs and especially complex therapeutic DNA and RNA sequences. For example, Harguindey et al. [87] conjugated a diblock copolymer of PEG and PLGA with thymine containing click nucleic acid, a synthetic DNA analog, by photoinitiated thiolene reaction to form Cy3-labeled adenine-based DNA-loaded nanoparticles. Unlike the nanoparticles made of PEG–PLGA copolymer, which entrapped only negligible amounts of DNA, the PEG-DNA-PLGA nanoparticles entrapped ~57.2 ±9.5 pmol of the DNA per mg of the nanoparticles. They were also able to load the hydrophobic compound pyrene along with the hydrophilic Cy3-labeled adenine-based DNA in the same nanoparticle owing to the different microenvironments created in the triblock copolymer nanoparticles owing to the inclusion of the oligonucleotide. Recently, DNA nucleotides have also been utilized as chemical crosslinkers in the preparation of nanogels and polymeric nanoparticles. Crosslinking using DNA strands requires binding of complementary DNA strands with the monomers to form DNA-bound prepolymers and, upon hybridization of the DNA strands, the desired nanoaggregate will be obtained (Figure 6a). Alternatively, the prepolymer can be joined with primary DNA strands and, upon adding a two-arm complementary DNA strand, prepolymer crosslinking occurs by hybridization to obtain the desired nanoaggregate without the need for an initiator or a catalyst (Figure 6b) [63,64,88]. Unlike the traditional crosslinkers, the length of the DNA crosslinker can also be easily varied because of the ease of obtaining oligonucleotides of up to 100 bases long (~34 nm) [88]. Drug release from such nanostructures can be induced at the target site by using complementary triggering sequences or removal strands, which reversibly interact with the third DNA sequences that contain a ‘toehold’ region (a short single-stranded overhanging region in which the invading strand can initially bind) [63,64,88]. Alternatively, the H-bonds between complementary base pairs can be dissociated at high temperatures rendering the nanocarriers thermoresponsive with a distinct melting point. The melting point can be varied by selecting appropriate oligomer lengths or base sequences [88]. For example, Liwinska et al. [89] polymerized two acrydite-modified oligodeoxynucleotides [5′-acrydite-GGGGG-GCTCTTGGAACT-3′ (M.pt = 57.3°C) and 5′-acrydite GGGGG-TGAGTAGACACT-3′ (M.pt = 53.0°C)] with N-isopropylacrylamide and acrylic acid mixture (9:1 molar ratio) and simultaneously crosslinked the prepolymers using a third oligodeoxynucleotide [5′-ACTCATCTGTGACGAGAACCTTGA-3′ (M.pt = 56.0°C)] complementary to the two oligodeoxynucleotides and thereby formed thermoresponsive poly(N-isopropylacrylamide-co-acrylic)acid-based biodegradable mimetic nanogels. The nanogels could load 83.7% doxorubicin, whereas nanogels synthesized by using traditional bis-crosslinkers could load only 31.0% doxorubicin. The nanogels crosslinked by oligodeoxynucleotides released ~40% of the doxorubicin over 20 h at 37°C and underwent temperature- and pH-dependent drug release. When the temperature was increased from 37 to 45°C the percentage of drug release increased by 25% and 75% at pH 7.4 and 5.5, respectively. When temperature was further increased to 70°C (temperature attained in vivo by a laser ablation high hyperthermia process) 98% and 70% doxorubicin was released at pH 5.5 and 7.4, respectively. The nanogels also decreased the IC50 of doxorubicin in β-TC3 insulinoma cell lines from 0.78 ±0.04 to 0.37 ±0.03 μM, at pH 5.5. Because DNA strands are negatively charged, they can be used to crosslink positively charged polymers like chitosan by electrostatic interaction to obtain DNA and chitosan nanoparticles that increase the cellular uptake of the nanoparticles. Wang and colleagues showed that DNA-crosslinked chitosan nanoparticles increased the uptake of astaxanthin by Caco-2 cells and the radical-oxygen-species-scavenging efficiency of astaxanthin by twofold compared with the free drug alone [90]. However, one of the drawbacks of using DNA strands as crosslinkers is that a significant amount of DNA sequences should be used to obtain sufficiently strong and swellable nanogels, which might be expensive or immunogenic [63,64].

Figure 6.

Schematic representation of the use of DNA crosslinkers in the preparation of nanogels or polymeric nanoparticles that respond to a specific strand displacement DNA. (a) The primary and complementary DNAs are attached to the monomer before polymerization. (b) Prepolymers are chemically crosslinked with the primary DNA and crosslinking was carried out using a two-arm complementary DNA.

Aptamer functionalized nanotherapeutics

Aptamers are artificially selected, short, single-stranded oligonucleotides that fold into unique 3D structures that bind to specific molecular targets such as small organic molecules, metals, proteins, receptors, viruses and cells with high affinity and specificity [64,91–94]. Like antibodies, they can be conjugated to nanocarriers, noncoding RNAs (such as miRNA, circRNA, lncRNA), proteins and other molecules to be used as targeting vectors [36,64]. However, in comparison with antibodies, aptamers are smaller in size, easier to synthesize and modify, chemically and physically more stable, less expensive, exhibit lower batch-to-batch variations and penetrate tissues more rapidly. They also have low immunogenicity, high affinity and specificity, and high design flexibility with further functionalization potentials [92,93,95,96]. They are normally selected from a large library of oligonucleotide sequences by an in vitro technology known as systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX) [95,97]. Accordingly, several aptamers have been identified and conjugated to various nanocarriers (Table 2) to increase their localization at specific cells or tissues, especially cancerous cells and tissues. DNA aptamers could also be conjugated to the pure and hybrid DNA nanomaterials discussed above (Figure 4d) to obtain the combined benefits of the programmable features of DNA nanomaterials and the targeting feature of aptamers (Table 2). Apart from nanocarrier-targeting abilities, aptamers have also been used to control drug release from DNA nanostructures. For example, Banerjee et al. [98] used the cyclicdi-GMP (cdGMP) aptamer (110Vc2) interaction with its ligand cdGMP to control the release of 10 kDa FITC dextran from a DNA icosahedron origami (Figure 7). They first assembled two hemi-icosahedra (which have ten projections) and loaded the model drug dextran in the hemi-icosahedra. Then they joined the hemi-icosahedra using ten parts of cdGMP aptamers to form a complete DNA icosahedron. Upon incorporation of cdGMP, the aptamers interacted with the cdGMP and dissociated from the DNA icosahedron origami to split the icosahedron into its two constituent halves and released the encapsulated dextran. A FRET assay showed that the incorporation of the cdGMP increased dextran release from the DNA icosahedron origami by about fourfold.

Table 2.

Examples of aptamer-conjugated nanotherapeutics designed to target specific cells or tissues and improve treatment effectiveness

| no. | Nanocarrier | Aptamer conjugated | Compound (s) loaded | Purpose/application | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Polymeric nanoparticle of a PEG–PCL copolymer | S15: an aptamer that binds specifically to lung cancer cells | Paclitaxel | A549 cells treated with the aptamer-conjugated nanoparticles completely died after 24 h of incubation owing to specificity of the aptamer to the cells. By contrast, all A549 cells treated with aptamer-free nanoparticles and HeLa cells treated with the aptamer-conjugated nanoparticle survived | [104] |

| 2. | Mesoporous silica nanoparticles | MUC1: a 25-mer aptamer that selectively binds to abnormally glycosylated mucin-1, which is overexpressed on breast, ovarian, pancreas, prostate, colon and lung cancer cells | Epirubicin | Aptamer conjugation improved the uptake of the nanoparticle by MCF-7 cells by >50% | [105] |

| 3. | Liposomes | An RNA aptamer specific to prostate-specific membrane ntigen | Doxorubicin | 12 and 24 h after i.v. administration to LNCaP xenograft-bearing BALB/c nude mice, the aptamer-conjugated liposome accumulated in tumor tissue as well as in the liver and kidney. Whereas, the plain liposomes distributed mainly in the liver and kidney without any accumulation in tumor tissue | [94] |

| 4. | Dendrimers: PEGylated polyamidoa mine | S6: aptamer against A549 lung cancer cells | MicroRNA-34a: a potent endogenous tumor suppressor in nonsmall-cell lung cancer cells | Aptamer conjugation enhanced dendrimer uptake, gene transfection and cellular apoptosis in A549 cells: the aptamerconjugated and the nonconjugated dendrimers transfected 37.9% and 9.5% of the cells, respectively. Besides, compared with cells treated with the plain dendrimer, the viability of cells treated with aptamer conjugated dendrimer decreased by 29.8%, 49.7%, 57.5% and 62.4% after 24 h, 48 h, 72 h and 96 h of transfection, respectively | [96] |

| 5. | Dendrimer: PEGylated polyamidoa mine | AS1411: an anticancer aptamer that is specifically internalized by cancer cells | Camptothec in | Fluorescent microscopic images showed that aptamer conjugation enhanced the uptake of the dendrimer by nucleolin overexpressing HT29 and C26 (mice colorectal carcinoma cell line) cells in vitro. Besides, 50 mm3 C26 tumor bearing BALB/c female mice were treated (3 mg/kg i.v. injection twice weekly for 3 weeks) with the dendrimers and the volume of the tumor in the aptamer conjugateddendrimer-treated group increased only to ~100 mm3 in contrast to the volume of tumor increased to about 1350, 850 and 440 mm3, in the control group and groups treated with the free drug and the non-aptamerconjugated drug-loaded dendrimer, respectively | [106] |

| 6. | Gold nanorod; PEGylated |

AS1411 | - | Nanorod cellular uptake investigation by far-field fluorescence microscopy showed that the aptamer-conjugated nanorods were taken up by HeLa cells. Whereas, the uptake of the parent gold nanorods was negligible | [93] |

| 7. | DNA nanoparticle (with a pH-sensitive spacer) | Prostate cancer membrane antigen (PCMA)-specific aptamer (added as a segment in the DNA nanoparticles) | Doxorubicin | The nanoparticle underwent pH-dependent drug release kinetics and was taken up by PCMA-positive C4–2 cells but not significantly by PCMA null PC-3 cells. The free doxorubicin, however, was indiscriminately taken up by both cell types | [97] |

| 8. | DNA tetrahedron | MUC 1 | Doxorubicin | CLSM investigation showed that the free doxorubicin and the free tetrahedron (to a lesser extent) were taken up indiscriminately by MUC1-positive MCF-7 and MUC1-ngeative MDA-MB-231 cells in vitro. By contrast, the aptamer-conjugated tetrahedron was preferentially taken up by the MUC1-positive MCF-7 cells: its uptake by MUC1-ngeative cells was negligible. Han et al. later showed that a similar nanocarrier significantly prolonged the duration of action and minimized the side effects of doxorubicin therapy in vivo in rats | [107, 108] |

| 9. | DNA tetrahedron | sgc8c: an aptamer that targets protein tyrosine kinase 7 (PTK7), which is overexpressed on many tumor cells | Doxorubicin | Aptamer conjugation increased doxorubicin uptake by about twofold in PTK7-positive CCRFCEM cells in vitro. However, there was no significant difference in doxorubicin uptake from aptamer-modified and non-modified tetrahedron in PTK7-negative Ramos cells | [109] |

| 10. | DNA icosahedron | MUC 1 | Doxorubicin | CLSM results showed that, unlike the doxorubicin and the doxorubicin-loaded icosahedron, the aptamer-conjugated icosahedron was efficiently internalized by MCF-7 cells that express MUC1. The CLSM results also showed that the nanoparticles were not internalized by Chinese hamster ovary cell lines (CHO-K1), which do not express MUC 1 | [110] |

| 11. | Triangular DNA origami | MUC 1 | Doxorubicin and gold nanorods (generated hyperthermi a when exposed to NIR and inhibited p-gp efflux) | Aptamer conjugation enhanced the uptake of the DNA origami in MCF-7/ADR cells by about twofold. In addition, upon exposure to NIR, the gold nanorods inhibited the P-gp efflux and maximized the activity of doxorubicin: the viability of the MCF-7/ADR cells treated with the free drug only was >80% but went down to <30% when treated with the aptamer-conjugated DNA origami | [111] |

| 12. | Cylindrical DNA origami: a rectangular DNA sheet formed from an M13 bacteriopha ge genome DNA strand was rolled up into a hollow tube of 100 nm using DNA fasteners | AS1411. When it comes in contact with nucleolin proteins (selectively expressed on the surface of actively proliferating tumor vascular endothelial cells), the hybridized duplexes dissociated to open up the tube into sheets and expose the cargo loaded inside the tube/cylinder | Thrombin bound to the inner surface of the tube via DNA tags (to induce local blood clotting and tumor necrosis) | After tail vein injection of the nanotubes to MDA-MB231 tumor-bearing nude mice, the targeted nanotubes accumulated 7-times higher than the nontargeted nanotube in 8 h. Upon repeated injection of the targeted nanotube (six times every 3 days), the tumor growth was substantially slow and the animal median survival time was 39 days as compared with the 29 days of median survival time for the mice treated with saline, the free thrombin, the empty nanotube or the nontargeted nanotube | [112] |

Figure 7.

Ten kDa FITC-dextran (green) was encapsulated in two semi-DNA icosahedrons (black) held together by ten aptamers (red) to form a complete DNA icosahedron. In the presence of the molecular trigger cdGMP (gray hexagons), the aptamers folded back leading to opening of the DNA icosahedron and simultaneous release of the encapsulated dextran. Figure reproduced, with permission, from [98].

Concluding remarks and future perspectives

Oligonucleotides or DNA strands have been utilized in various ways to design programmable nanotherapeutics that are responsive to biomolecules. The first approach is to form pure DNA nanomaterials by either self-assembling of multiple oligonucleotide strands by specific DNA base-pairing or by folding and binding of a ssDNA scaffold using staple strands into in silico designed, well-defined, 2D and 3D DNA origamis. Unlike many nanotherapeutics, these nanotherapeutics are monodispersed systems with the same size, shape and charge distribution and enable perfect control of the placement of functionalities on the nanostructure using specific oligonucleotide sequences. The second approach is to use DNA strands as building blocks of various hybrid DNA nanostructures. In this case, the DNA strands can either be conjugated to form amphiphilic DNA–polymer or DNA–lipid conjugates that self-assemble into micellar, vesicular structures or DNA strands, or be used to modify the surfaces and/or matrixes of other nanomaterials to enhance their tissue targeting and cellular permeability potentials. It is now understood that pure and hybrid DNA nanostructures undergo class A scavenger receptor-mediated cell binding and caveolin-1-mediated endocytosis. The third approach is to conjugate selected DNA sequences called aptamers to different nanostructures to target the nanocarriers to the desired cells or tissues. The aptamers are obtained by the process of SELEX, which enables the generation of numerous aptamers for targeted delivery of numerous nanocarriers and macromolecules. Drug release from all the DNA nanocarriers is possible by careful introduction of a complementary DNA strand, which interacts with the DNA building blocks and modifies their nanostructure, and/or by the action of body nucleases that slowly degrade the random nucleotide sequences. Accordingly, several programmable nucleic-acid-based nanotherapeutics with improved drug loading, cell permeability, targeting and release profiles have been developed and characterized. However, mostly these nanostructures were investigated in vitro in cell culture media and lacked adequate in vivo supporting data. In addition, the stability of nucleic-acid-based nanostructures or nanocarriers in low salt concentration and acidic physiological fluids and the presence of endonuclease is a concern [99]. In the future, oligonucleotide-based nanomaterials should be designed and optimized with the structures and architectures that can increase their stability under physiological conditions, enhance the loading efficiency, cell and tissue penetration and targeting of therapeutics, and control and sustain the release of therapeutics in response to biomolecule stimuli in a rapid response manner. Significant future efforts should be also focused on the in vivo evaluations of oligonucleotide-based nanomaterials including toxicology, off-target delivery, pharmacokinetics (absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion), pharmacodynamics, immunogenicity, stability and therapeutic effects. Clinical trials, product stability assessment and scale-up manufacturing of oligonucleotide-based nanomaterials are expected after sufficient positive animal data, in terms of safety and therapeutic effects, are generated in the future [99].

Highlights.

Design principles and strategies for pure and hybrid DNA nanostructures were reviewed

The application of DNA as nanocarrier surface and matrix modifier was summarized

The applications of DNA aptamers as nanotherapeutic targeting agents were compiled

The uses of DNA nanostructures as a drug and gene delivery system were discussed

Limitations and future perspectives of oligonucleotide nanotherapeutics were addressed

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by NIH R01EY023853.

Abbreviations:

- CpG-ODN

cytosine-phosphate-guanine oligodeoxynucleotides

- CLSM

confocal laser scanning microscope

- dsDNA

double-stranded DNA

- PEG

polyethylene glycol

- PLGA

poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)

- SNA

spherical nucleic acid nanoparticles

- siRNAs

small interfering RNAs

- ssDNA

single-stranded DNA

Biographies

Fitsum F. Sahle

Dr Fitsum F. Sahle earned a PhD in pharmaceutical technology and biopharmaceutics from Martin Luther University, Halle/Saale, Germany. After his PhD he worked for two and half years as an Assistant Professor at the School of Pharmacy, Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia. Later, he joined the Freie Universität Berlin, Germany, as an Alexander von Humboldt/George-Forster Postdoctoral Fellow and worked for ~3 years in areas of nanotechnology and transdermal and transfollicular drug delivery. Currently, Dr Sahle is a postdoctoral fellow in Dr Lowe’s lab and is working on development of smart polymeric nanomaterials for drug delivery and tissue engineering.

Tao Lowe

Dr Tao Lowe is currently an Associate Professor of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Biomedical Engineering at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center. Her research activities include design and development of multifunctional biomaterials for targeted and sustained drug and gene delivery, regenerative medicine, stem cell engineering and biosensoring for the treatments and diagnoses of brain and eye diseases, diabetes, cancers, bone fractures and cartilage damage, as well as contraception. She has many high-impact peer-reviewed articles and US and international patents; and has lectured extensively throughout the global scientific community. Her research has been supported by NIH, DOD, Coulter Foundation and JDRF, among others.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Gil ES et al. (2012) β-Cyclodextrin-poly(β-amino ester) nanoparticles for sustained drug delivery across the blood–brain barrier. Biomacromolecules 13, 3533–3541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gil ES et al. (2009) Quaternary ammonium beta-cyclodextrin nanoparticles for enhancing doxorubicin permeability across the in vitro blood–brain barrier. Biomacromolecules 10, 505–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sahle FF et al. (2016) Formulation and in vitro evaluation of polymeric enteric nanoparticles as dermal carriers with pH-dependent targeting potential. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci 92, 98–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sahle FF et al. (2017) Formulation and comparative in vitro evaluation of various dexamethasone-loaded pH-sensitive polymeric nanoparticles intended for dermal applications. Int. J. Pharm 516, 21–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Müller RH et al. (2000) Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN) for controlled drug delivery – a review of the state of the art. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm 50, 161–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hua MY et al. (2011) The effectiveness of a magnetic nanoparticle-based delivery system for BCNU in the treatment of gliomas. Biomaterials 32, 516–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Landon CD. et al. (2011) Nanoscale drug delivery and hyperthermia: the materials design and preclinical and clinical testing of low temperature-sensitive liposomes used in combination with mild hyperthermia in the treatment of local cancer. The Open Nanomedicine Journal 3, 38–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bulbake U et al. (2017) Liposomal formulations in clinical use: an updated review. Pharmaceutics 9, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colombo M et al. (2017) In situ determination of the saturation solubility of nanocrystals of poorly soluble drugs for dermal application. Int. J. Pharm 521, 156–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xuan J et al. (2012) Ultrasound-Responsive Block Copolymer Micelles Based on a New Amplification Mechanism. Langmuir 28 (47), 16463–16468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sahle FF et al. (2012) Polyglycerol fatty acid ester surfactant-based microemulsions for targeted delivery of ceramide AP into the stratum corneum: formulation, characterisation, in vitro release and penetration investigation. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm 82, 139–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sahle FF et al. (2013) Lecithin-based microemulsions for targeted delivery of ceramide AP into the stratum corneum: formulation, characterizations, and in vitro release and penetration studies. Pharm. Res 30, 538–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lorenceau E et al. (2005) Generation of polymerosomes from double-emulsions. Langmuir 21, 9183–9186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim YS et al. (2006) Synthesis and characterization of thermoresponsive-co-biodegradable linear-dendritic copolymers. Macromolecules 39, 7805–7811 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stover TC et al. (2008) Thermoresponsive and biodegradable linear-dendritic nanoparticles for targeted and sustained release of a pro-apoptotic drug. Biomaterials 29, 359–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim YS et al. (2018) Thermoresponsive-co-biodegradable linear-dendritic nanoparticles for sustained release of nerve growth factor to promote neurite outgrowth. Mol. Pharm 15, 1467–1475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang X et al. (2008) Novel nanogels with both thermoresponsive and hydrolytically degradable properties. Macromolecules 41, 8339–8345 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sahle FF et al. (2017) Dendritic polyglycerol and N-isopropylacrylamide based thermoresponsive nanogels as smart carriers for controlled delivery of drugs through the hair follicle. Nanoscale 9, 172–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu X et al. (2014) Electrospinning of polymeric nanofibers for drug delivery applications. J. Control. Release 185 (suppl. C), 12–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharma HS et al. (2007) Drug delivery to the spinal cord tagged with nanowire enhances neuroprotective efficacy and functional recovery following trauma to the rat spinal cord. Annal. N. Y. Acad. Sci 1122, 197–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yilmaz C et al. (2016) Novel nanoprinting for oral delivery of poorly soluble drugs. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc. J 12, 157–162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jafari S et al. (2017) Biomacromolecule based nanoscaffolds for cell therapy. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol 37 (suppl. C), 61–66 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu Q et al. (2013) Nanopatterned smart polymer surfaces for controlled attachment, killing, and release of bacteria. ACS Appl. Mater. Interface 5, 9295–9304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DeLeon VH et al. (2012) Polymer nanocomposites for improved drug delivery efficiency. Mater. Chem. Phys 132, 409–415 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duan CH et al. (2013) Review article: fabrication of nanofluidic devices. Biomicrofluidics 7, 026501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang W et al. (2011) The application of carbon nanotubes in target drug delivery systems for cancer therapies. Nanoscale Res. Lett 6, 555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen W et al. (2017) Black phosphorus nanosheet-based drug delivery system for synergistic photodynamic/photothermal/chemotherapy of cancer. Adv. Mater 29, 1603864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jeon G et al. (2012) Functional nanoporous membranes for drug delivery. J. Mater. Chem 22, 14814–14834 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Janagam DR et al. (2017) Nanoparticles for drug delivery to the anterior segment of the eye. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev 122, 31–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu L et al. (2014) Overcoming the blood–brain barrier in chemotherapy treatment of pediatric brain tumors. Pharm. Res 31, 531–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sahle FF et al. (2014) Controlled penetration of ceramides into and across the stratum corneum using various types of microemulsions and formulation associated toxicity studies. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm 86, 244–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Balzus B et al. (2017) Formulation and ex vivo evaluation of polymeric nanoparticles for controlled delivery of corticosteroids to the skin and the corneal epithelium. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm 115, 122–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sahle FF et al. (2018) Design strategies for physical-stimuli-responsive programmable nanotherapeutics. Drug Discov. Today 23, 992–1006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gulfam M et al. (2018) Design strategies for chemical-stimuli-responsive programmable nanotherapeutics. Drug Discov. Today 24, 129–147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hamblin GD et al. (2012) Rolling circle amplification-templated DNA nanotubes show increased stability and cell penetration ability. J. Am. Chem. Soc 134, 2888–2891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li J et al. (2013) Smart drug delivery nanocarriers with self-assembled DNA nanostructures. Adv. Mater 25, 4386–4396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peterson AM and Heemstra JM (2015) Controlling self-assembly of DNA-polymer conjugates for applications in imaging and drug delivery. Nanomedicine Nanobiotechnology 7, 282–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jones MR et al. (2015) Programmable materials and the nature of the DNA bond. Science 347, 6224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cubero E et al. (2006) Theoretical study of the Hoogsteen–Watson-Crick junctions in DNA. Biophys. J 90, 1000–1008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Strauch MA (2001) Protein–DNA complexes: specific. eLS doi: 10.1038/npg.els.0001357 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bailly C and Chaires JB (1998) Sequence-specific DNA minor groove binders. Design and synthesis of netropsin and distamycin analogues. Bioconjug. Chem 9, 513–538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pei H et al. (2010) A DNA nanostructure-based biomolecular probe carrier platform for electrochemical biosensing. Adv. Mater 22, 4754–4758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Douglas SM et al. (2007) DNA-nanotube-induced alignment of membrane proteins for NMR structure determination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 104, 6644–6648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tan SJ et al. (2011) Building plasmonic nanostructures with DNA. Nat. Nanotechnol 6, 268–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu X et al. (2012) A DNA nanostructure platform for directed assembly of synthetic vaccines. Nano Lett 12 doi: 10.1021/n1301877k [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Piana R (2019) Human gene therapy: progress and oversight. The ASCO Post [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rush AM et al. (2013) Nuclease-resistant DNA via high-density packing in polymeric micellar nanoparticle coronas. ACS Nano 7, 1379–1387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kwak M and Herrmann A (2010) Nucleic acid/organic polymer hybrid materials: synthesis, superstructures, and applications. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 49, 8574–8587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Radovic-Moreno AF et al. (2015) Immunomodulatory spherical nucleic acids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 112, 3892–3897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Choi CHJ et al. (2013) Mechanism for the endocytosis of spherical nucleic acid nanoparticle conjugates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 110, 7625–7630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rush AM et al. (2014) Intracellular mRNA regulation with self-assembled locked nucleic acid polymer nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc 136, 7615–7618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thompson MP et al. (2010) Smart lipids for programmable nanomaterials. Nano Lett 10, 2690–2693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mou Q et al. (2017) DNA Trojan horses: self-assembled floxuridine-containing DNA polyhedra for cancer therapy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 56, 12528–12532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bhatia D et al. (2011) A synthetic icosahedral DNA-based host–cargo complex for functional in vivo imaging. Nat. Commun 2, 339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rothemund PWK (2006) Folding DNA to create nanoscale shapes and patterns. Nature 440, 297–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Samanta A and Medintz IL (2016) Nanoparticles and DNA – a powerful and growing functional combination in bionanotechnology. Nanoscale 8, 9037–9095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang Q et al. (2014) DNA origami as an in vivo drug delivery vehicle for cancer therapy. ACS Nano 8, 6633–6643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Halley PD et al. (2016) Daunorubicin-loaded DNA origami nanostructures circumvent drug-resistance mechanisms in a leukemia model. Small 12, 308–320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhuang X et al. (2016) A photosensitizer-loaded DNA origami nanosystem for photodynamic therapy. ACS Nano 10, 3486–3495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhao S et al. (2019) Efficient intracellular delivery of RNase A using DNA origami carriers. ACS Appl. Mater. Interface 11, 11112–11118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hoiberg HC et al. (2019) An RNA origami octahedron with intrinsic siRNAs for potent gene knockdown. Biotechnol. J 14, e1700634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ora A et al. (2016) Cellular delivery of enzyme-loaded DNA origami. Chem. Commun 52, 14161–14164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sicilia G et al. (2014) Programmable polymer-DNA hydrogels with dual input and multiscale responses. Biomater. Sci 2, 203–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stejskalova A et al. (2016) Programmable biomaterials for dynamic and responsive drug delivery. Exp. Biol. Med 241, 1127–1137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bastings MMC et al. (2018) Modulation of the cellular uptake of DNA origami through control over mass and shape. Nano Lett 18, 3557–3564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jiang Q et al. (2012) DNA origami as a carrier for circumvention of drug resistance. J. Am. Chem. Soc 134, 13396–13403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhao Y-X. et al. (2012) DNA origami delivery system for cancer therapy with tunable release properties. ACS Nano 6, 8684–8691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li J et al. (2011) Self-assembled multivalent DNA nanostructures for noninvasive intracellular delivery of immunostimulatory CpG oligonucleotides. ACS Nano 5, 8783–8789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ko S et al. (2008) DNA nanotubes as combinatorial vehicles for cellular delivery. Biomacromolecules 9, 3039–3043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Keum JW and Bermudez H (2009) Enhanced resistance of DNA nanostructures to enzymatic digestion. Chem. Commun 45, 7036–7038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Surana S et al. (2015) Designing DNA nanodevices for compatibility with the immune system of higher organisms. Nat. Nanotechnol 10, 741–747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mei Q et al. (2011) Stability of DNA origami nanoarrays in cell lysate. Nano Lett 11, 1477–1482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lee H et al. (2012) Molecularly self-assembled nucleic acid nanoparticles for targeted in vivo siRNA delivery. Nat. Nanotechnol 7, 389–393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Xia Z et al. (2016) Tumor-penetrating peptide-modified DNA tetrahedron for targeting drug delivery. Biochemistry 55, 1326–1331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Setyawati MI et al. (2016) DNA nanostructures carrying stoichiometrically definable antibodies. Small 12, 5601–5611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Schüller VJ et al. (2011) Cellular immunostimulation by CpG-sequence-coated DNA origami structures. ACS Nano 5, 9696–9702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shen C et al. (2016) Site-specific surface functionalization of gold nanorods using DNA origami clamps. J. Am. Chem. Soc 138, 1764–1767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jeong JH and Park TG (2001) Novel polymer-DNA hybrid polymeric micelles composed of hydrophobic poly(D,l-lactic-co-glycolic acid) and hydrophilic oligonucleotides. Bioconj. Chem 12, 917–923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhang C et al. (2015) Biodegradable DNA-brush block copolymer spherical nucleic acids enable transfection agent-free intracellular gene regulation. Small 11, 5360–5368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Alemdaroglu FE et al. (2008) DNA block copolymer micelles – a combinatorial tool for cancer nanotechnology. Adv. Mater 20, 899–902 [Google Scholar]

- 81.Banga RJ et al. (2017) Drug-loaded polymeric spherical nucleic acids: enhancing colloidal stability and cellular uptake of polymeric nanoparticles through DNA surface-functionalization. Biomacromolecules 18, 483–489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]