Abstract

Background.

Sleep problems and depression are highly prevalent in pregnancy. Nocturnal rumination has been linked to insomnia and depression in non-pregnant samples, but remains poorly characterized in pregnancy. This study explored relationships of depression and suicidal ideation with insomnia, short sleep, and nocturnal rumination in mid-to-late pregnancy.

Methods.

267 pregnant women were recruited from obstetric clinics and completed online surveys on sleep, depression, and nocturnal rumination.

Results.

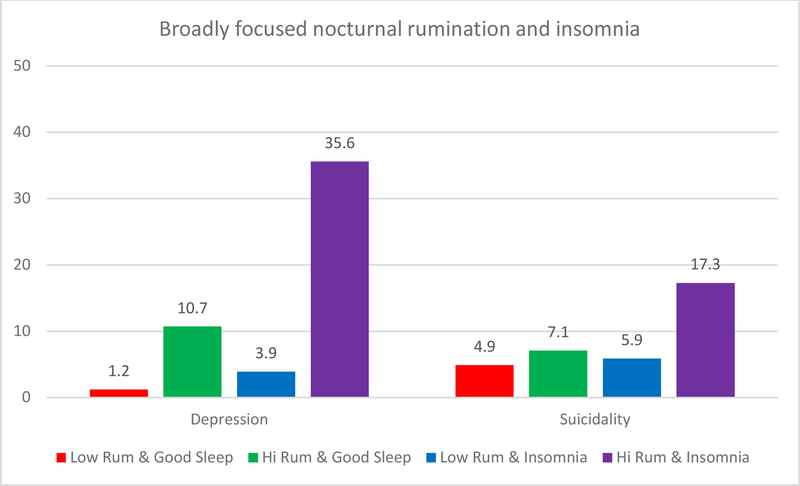

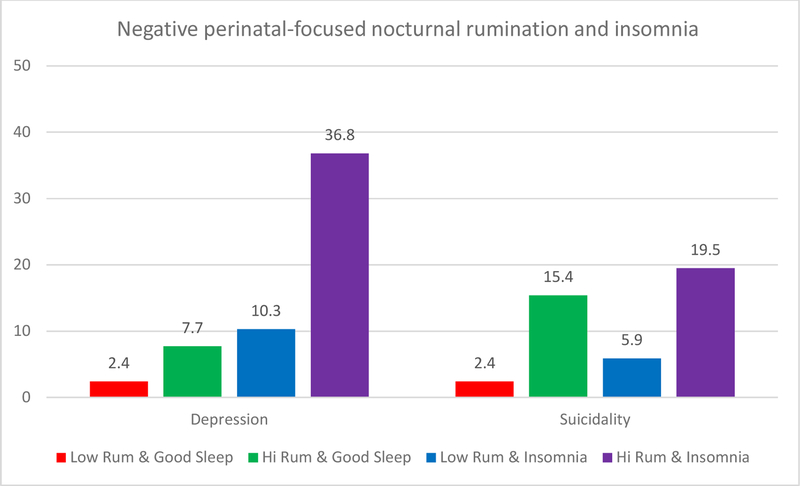

Over half (58.4%) of the sample reported clinical insomnia on the Insomnia Severity Index, 16.1% screened positive for major depression on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, and 10.1% endorsed suicidal ideation. Nocturnal rumination was more robustly associated with sleep onset difficulties than with sleep maintenance issues. Depressed women were at greater odds of sleep onset insomnia (OR=2.80), sleep maintenance insomnia (OR=6.50), high nocturnal rumination (OR=6.50), and negative perinatal-focused rumination (OR=2.70). Suicidal ideation was associated with depression (OR=3.64) and negative perinatal-focused rumination (OR=3.50). A four-group comparison based on insomnia status and high/low rumination revealed that pregnant women with insomnia and high rumination endorsed higher rates of depression (35.6%) and suicidal ideation (17.3%) than good-sleeping women with low rumination (1.2% depressed, 4.9% suicidal). Women with insomnia alone (depression: 3.9%, suicidal: 5.9%) or high rumination alone (depression: 10.7%, suicidal: 7.1%) did not differ from good-sleeping women with low rumination.

Conclusions.

High rumination and insomnia are highly common in mid-to-late pregnancy and both are associated with depression and suicidal ideation. Depression and suicidal ideation are most prevalent in pregnant women with both insomnia and high rumination.

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier:

Keywords: worry, cognitive arousal, pre-sleep arousal, perinatal, prenatal, stress, suicidality

INTRODUCTION

Pregnancy is stressful for many women1 and stress-related disorders such as insomnia and depression are highly prevalent during this period.2,3 Over half of women in mid-to-late pregnancy endorse clinical insomnia,4–6 which far exceeds rates of 10–20% in the general adult population.7–9 Similarly, 10–15% of pregnant women are afflicted with major depression and even more are affected when considering subclinical elevations in depressive symptoms.3,4,10 Insomnia and depression are closely connected during pregnancy, particularly when insomnia presents with prolonged sleep latency and short sleep duration.4,11,12 The relationship between insomnia and depression, however, is not simply a product of sleep loss or fatigue, but rather modulated by stress-related emotion dysregulation.13–15 The stress-response has thus far been under-emphasized in understanding the relationship between insomnia and depression during pregnancy.

Rumination (repetitive negative thinking) is a common but harmful emotion regulation strategy for many individuals with insomnia.16–18 Importantly, insomniacs are especially prone to ruminating at night, particularly as they try to fall asleep, when people are socially isolated in bed with few distractions thereby untethering a wander-prone mind.17–19 Yet, little is known about rumination (nocturnal or otherwise) and its associations with insomnia during pregnancy. Evidence suggests that pregnant women worry excessively, that prenatal insomnia symptoms and sleep quality ratings are correlated with ruminative thinking,12,20 and that they often ascribe sleep difficulties to intrusive thoughts.21 However, the extent to which pregnant women ruminate at night and the manner in which this nocturnal cognitive phenomenon is related to prenatal insomnia is unclear. This is a shortcoming as improved characterization of nocturnal rumination in this population may offer critical insights into stress-related cognitive processes complicit in high levels of insomnia during pregnancy as well into therapeutic approaches to pregnancy-related insomnia.

Importantly, rumination in pregnancy is not only associated with insomnia. A small extant literature has focused on rumination in perinatal depression, although much of it has focused on depression after childbirth rather than during pregnancy.22 One study on prenatal depressive symptoms suggests that women who ruminate on stress while pregnant are at elevated risk for depression before childbirth.23 This finding is consistent with the well-supported role of rumination in depression etiology24–27 and maintenance28 in the broader population. Another relevant study focused on the content of perinatal fears and their associations with psychiatric illness. Although the study did not assess rumination per se, the authors showed that perinatal women with clinical depression (with and without comorbid anxiety) were more likely to endorse concerns regarding pregnancy, childbirth, and motherhood than psychologically healthy women.29 Despite the evidence from separate lines of research showing that rumination is related to both perinatal insomnia and depression, investigations linking rumination with both perinatal insomnia and depression are lacking.

Despite early evidence that stress and emotion dysregulation may be linked to prenatal insomnia and depression, the extant literature is limited in two key ways: First, the scope of interest on rumination in perinatal research has been very limited. Prospective data in the broader population show that insomnia and high rumination alone do not significantly increase depression-risk, but rather that individuals with both insomnia and high rumination are at marked risk for future depression,30 just as already afflicted depressed individuals report high insomnia and rumination.28,31 However, the independent and combined associations of insomnia and rumination with depression in pregnant women have not been examined. Importantly, nocturnal rumination has not been explored in pregnancy, even though pregnancy is stressful for many women,1 women (relative to men) are highly ruminative when stressed,28 and women endorse high rumination at night.32 Related, we are aware of no studies that have focused on rumination specifically regarding perinatal concerns, which may be particularly germane for this patient population as ruminative thoughts tend to focus on individuals’ greatest concerns. If pregnancy is stressful, then ruminating on pregnancy and fetal/infant related concerns may be especially relevant to symptoms of insomnia and depression in this population.

Second, we know very little about the role of rumination within insomnia and suicidal ideation during pregnancy. Poor sleep quality is associated with suicidal ideation during pregnancy,33,34 and rumination has been proposed as a potential mediator of the insomnia-suicidality risk relationship in the broader population.35 But we are aware of no investigations that have explored the independent associations across insomnia, rumination, depression, and suicidal ideation during pregnancy.

Third, and unrelated to rumination, the combination of short sleep and insomnia disorder is associated with severe neurobiological stress dysregulation36 and heightened depression-risk.37 Despite high rates of short sleep in pregnancy,6 investigations have yet to examine independent and combined associations of insomnia and short sleep with perinatal mental illness.

The current study examined overall reports of insomnia, sleep duration, nocturnal rumination, depression, and suicidal ideation in women nearing or beginning the 3rd trimester of pregnancy. We first sought to explore the associations among sleep symptoms, rumination (broadly focused and perinatal-specific), depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation via group comparisons. We then explored specificity among these factors using multivariate analyses. We have previously reported on prenatal sleep disparities related to poverty, race, and obesity,38 thus here we also accounted for these sleep inequalities and explored potential disparities in rumination, depression, and suicidal ideation. Lastly, we compared odds of endorsing major depression and suicidal ideation for the following groups: (1) low ruminators without insomnia, (2) low ruminators with insomnia, (3) high ruminators without insomnia, and (4) high ruminators with insomnia. Consistent with prior data suggesting that insomnia and rumination have synergistic effects,30 we predicted that pregnant women with insomnia and high nocturnal rumination would be at greatest odds of endorsing major depression and suicidal ideation. We then repeated this four-group comparison based on insomnia status and short sleep, and predicted pregnant women with insomnia and short sleep would be at greater odds of endorsing depression/suicidality than the other three groups.

METHODS

Participants and procedures

The present study was conducted in a 6-hospital health system in Metro Detroit. All procedures were approved by the institutional review board. The study was part of a randomized controlled trial (RCT) comparing digital/internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia vs sleep hygiene education on perinatal insomnia. Data collected in this phase of the study were used to screen for eligibility into the RCT. Pregnant women receiving prenatal care in the health system’s obstetrics clinics were invited to complete this portion of the study. Due to our focus on mid-to-late pregnancy, only women in the late second trimester and early third trimester were contacted. Invitations advertising a study on perinatal sleep (without mentioning either that we were focused on poor sleep or that we were evaluating sleep treatments) were sent via email and phone calls to 3585 pregnant obstetric patients. A total of 535 women contacted us with interest in our study. Of these women, 272 women consented to completing the online surveys, 267 of whom provided sufficient data for analysis, which were collected between September 12, 2018 through March 9, 2019.

Measures

Sleep measures.

Insomnia symptoms were measured using the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI).39 Total scores on the ISI represent overall insomnia symptom levels with higher scores indicating greater severity. Subjects who reported ISI scores ≥ 10 were classified as having insomnia, which is consistent with epidemiological data from community samples.40 We assessed sleep latency, sleep onset insomnia symptoms, sleep maintenance insomnia symptoms and sleep duration using items from the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index41 (PSQI). Specifically, sleep latency was reported in minutes (item #2). Sleep duration was reported in half-hour increments (item 4a) and those who reported sleeping < 6 h/night were categorized as having short sleep, whereas those sleeping ≥ 6 h/night were categorized as having normal sleep duration. Sleep onset insomnia symptoms (SOI; item 5a: endorsing inability to fall asleep within 30 m on ≥ 3 nights/week) and sleep maintenance insomnia symptoms (SMI; item 5b: endorsing difficulties with nighttime awakening and/or early morning awakenings on ≥ 3 nights/week) were also assessed using the PSQI. This method of classifying SOI symptoms with the PSQI has been supported by prior research,42–44 and this short sleep cutoff is consistent with current practices for both objective and self-reported sleep duration.36,45 In addition to these measures, subjects were assessed for snoring, which is a prognostic marker for sleep disordered breathing.46

Depression.

Depressive symptoms were measured using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS),47 a 10-item self-report measure of depressive symptoms. EPDS scores range from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating greater severity. A cut-point of EPDS ≥ 10 favors sensitivity over specificity to detect both minor and major depression and is commonly used in clinical practice to initiate treatment for perinatal depression. By comparison, EPDS scores ≥ 13 suggest probable major depression.48 Suicidal ideation was measured with EPDS item #10 (‘The thought of harming myself has occurred to me’) such that any endorsement was classified as being a positive case for suicidal ideation.

Rumination.

The Presleep Arousal Scale Cognitive factor (PSAS-C)49 was used to measure nocturnal rumination specific to the presleep period, i.e., cognitive activity and arousal when trying to fall asleep. The PSAS-C consists of 8 items (e.g., ‘review or ponder events of the day’ and ‘can’t shut off your thoughts’) and scores range from 8 to 40 with higher scores indicating greater presleep cognitive arousal. We are not aware of any clinical cutoffs for the PSAS-C, but multiple untreated insomnia samples have reported mean PSAS-C scores > 16 (i.e., mean item response > 2 indicating ‘moderately’ to ‘extremely’), whereas average PSAS-C scores for good sleepers is < 13.50–53 In the present study, subjects who scored above the sample’s PSAS-C median score of 18 were classified as high ruminators, whereas those who scored at the median or below were classified as low ruminators. Additionally, for this study we created two perinatally focused rumination items and administered them with the 8 standard PSAS-C items. These items were kept separate when scoring the PSAS-C, so the PSAS-C in this study represents responses to only the standard 8 items. Positive perinatal nocturnal rumination was assessed by asking subjects how intensely they ‘had happy thoughts about your pregnancy or new infant’ when attempting to fall asleep. Negative perinatal nocturnal rumination was assessed by asking subjects how intensely they ‘worried or had stressful thoughts about your pregnancy or new infant’ when attempting to fall asleep. Because these items were administered with the PSAS-C, responses ranged from 1 (not at all) through 3 (moderately) up to 5 (extremely).

Sociodemographic characteristics, medical information, and pregnancy-related factors were reported by subjects via an online survey, except for body mass index (BMI) during pregnancy, which was recorded from electronic medical records based on data collected from the obstetrics appointment closest to their study participation. Poverty was operationalized as a household income < $20,000, which is consistent with the US poverty line of $21,330 for a household of 3 per the US Department of Health and Human Services 2019 Poverty Guidelines and with the operationalization used in a recent large-scale epidemiological study on disparities in sleep symptoms.54 For our racial comparisons of sleep parameters, we compared only women who self-identified as non-Hispanic white and non-Hispanic black as these were the only two groups with sufficient representation for analysis. For our obesity-related comparisons, we used a cutoff of BMI ≥ 35 representing severe obesity, which reflects criteria from the widely-used STOP-BANG sleep apnea screener55 and is consistent with the clinical cutoff utilized in our prior report on sleep disparities.38

Analyses

All analyses were conducted in SPSS version 25. We first characterized sociodemographics, pregnancy-related information, sleep, and emotion dysregulation for the full sample. Next, we explored our data by running a series of independent t-tests to compare groups based on insomnia symptoms, sleep duration, snoring, high vs low rumination, depression status, and suicidal ideation on clinically relevant sleep and emotion regulation-related factors. As group comparisons were provided more for summary than evaluation of substantive hypotheses, we then ran three multivariate logistic regressions to examine the unique associations of sleep symptoms and emotion dysregulation in predicting nocturnal rumination, depression status, and suicidal ideation. By employing independent samples t-tests for summary then multiple regression to evaluate specificity of associations, we are afforded the opportunity to observe any potential changes among associations while exercising statistical control.

Lastly, we explored nocturnal rumination and short sleep separately as potential augmentors of the depressogenicity and suicidogenicity of insomnia. To do so, we first reported rates of depression and suicidal ideation across four groups: (1) low ruminators with good sleep, (2) low ruminators with insomnia, (3) high ruminators with good sleep, and (4) high ruminators with insomnia. Next, we used dummy coded logistic regression to compare odds of endorsing depression/suicidality among groups of insomniacs and high ruminators relative to the low ruminators without insomnia as the reference group. Secondly, we repeated this process for these four groups: (1) non-insomniacs with normal sleep duration (reference group in dummy coded logistic regression model), (2) non-insomniacs with short sleep, (3) insomniacs with normal sleep duration, and (4) short sleeping insomniacs.

RESULTS

Sample characteristics and sociodemographics

The average age for women was 29.76 years (±4.72) and all were in the 2nd or 3rd trimester. Average BMI was in the moderately obese range and 21.8% of the sample was classified as having class II-III obesity. Most women planned their current pregnancy (65.5%) and 22.8% reported a history of miscarriage. Prior childbirth had been reported by 64.0% of the sample and depressive symptoms did not differ between primiparous and multiparous women (t[265]=.48, p=.63). Rates of diabetes (all cases were gestational) and hypertension (pre-pregnancy and gestational) and pre-eclampsia (clinical signs and diagnosis) were each < 5%. An estimated 17.2% of the sample reported living in poverty and 29.2% of the sample had Medicaid insurance coverage. Slightly over half of the sample identified as non-Hispanic white and a little more than a quarter identified as non-Hispanic black. Other racial categories each represented < 5% of the sample. Sample demographics, sleep symptoms, depression, and nocturnal rumination are reported in Table 1. Please refer to Supplementary Table 1 for additional data on pregnancy-related information, relationship status, and medical conditions.

Table 1.

Sample demographics, sleep, and psychological characteristics (n=267).

| Age | 29.76±4.72, 20–44 | ISI | 11.12±6.03 |

| Gestational week | 27.99±1.20, 25–37 | ISI ≥ 10 | 156/267; 58.4% |

| BMI, at assessment | 30.65±7.16 | Sleep latency (min) | 32.61±25.99 |

| Poverty | 45/261; 17.2% | Sleep duration (hrs) | 6.61±1.35 |

| Medicaid | 78/267; 29.2% | < 6 hrs/night | 65/267; 24.3% |

| Race | Snoring | 81/265; 30.6% | |

| White | 149/267; 55.8% | PSAS, Cognitive | 19.66±7.25 |

| Black | 73/267; 27.3% | Median | 18 |

| Asian | 11/267; 4.1% | PPNR | 3.24±1.32 |

| Middle Eastern or Arab | 12/267; 4.5% | NPNR | 2.44±1.14 |

| Hispanic or Latinx | 10/267; 3.7% | EPDS | 7.36±5.29 |

| Other | 1/267; 0.4% | EPDS ≥ 10 | 91/267; 34.1% |

| Multiracial | 11/267; 4.1% | EPDS ≥ 13 | 34.1/267; 16.1% |

| Suicidal ideation | 27/267; 10.1% | ||

Note: BMI = body mass index (kg/m2), derived from electronic medical records. ISI = insomnia severity index. PSAS, Cognitive = presleep arousal scale, cognitive factor. PPR = positive perinatal nocturnal rumination. NPNR = negative perinatal nocturnal rumination. EPDS = Edinburgh postnatal depression scale.

Sleep symptoms, depression, suicidal ideation, and nocturnal rumination

Over half of the sample screened positive for clinically significant insomnia (ISI≥10: 58.4%; see Table 1 for full results) and average sleep latency of 32.61±25.99 exceeded quantitative criteria for insomnia disorder.56 Average nightly sleep duration was 6 h and 37 m (±81 m) with 24.3% of the sample sleeping < 6 h/night. Snoring was endorsed by 30.6% of the sample. Over one-third of the sample screened positive for minor or major depression (EPDS ≥ 10), whereas 16.1% of women screened positive for major depression (EPDS ≥ 13) and 10.1% endorsed suicidal ideation.

Nocturnal rumination scores as measured by the PSAS-C were similar to those reported by patients with insomnia, psychiatric illness, and chronic pain.50–53 The average positive perinatal nocturnal rumination score was 3.24±1.32 and the average negative perinatal nocturnal rumination score was 2.44±1.14. As these items were created and added to the PSAS-C for this study (note: these item scores are not included in the PSAS-C score), no normative or other comparison data exist. However, for context, the average item score on the PSAS-C in this sample was 2.46. When comparing this average item-response to perinatal nocturnal rumination responses, our data may suggest that pregnant women engage in especially high levels of positive perinatal rumination when trying to fall asleep. Further, pregnant women may also engage in high levels of negative perinatal nocturnal rumination, as mean responses to this item were similar to mean responses to PSAS-C items in this sample (and this sample endorsed nocturnal rumination levels consistent with clinical populations).

Comparing sleep, rumination, and depressive features based on insomnia, short sleep, and snoring

As expected, pregnant women with clinical insomnia (ISI≥10), SOI symptoms, SMI symptoms, and short sleep endorsed more sleep disturbances than good sleepers (see Table 2 for full results). However, snorers did not differ from non-snorers on sleep disturbance parameters.

Table 2.

Comparing sleep and psychological characteristics based on insomnia symptoms, short sleep, and snoring.

| No insomnia n=111/267 |

Insomnia n=156/267 |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep latency | 20.95±12.03 | 40.97±29.84 | t=6.69***, d=.88 |

| Sleep duration | 7.34±1.10 | 6.08±1.26 | t=−8.50***, d=1.07 |

| PSAS, Cognitive | 15.27±4.83 | 22.77±7.08 | t=9.64***, d=1.24 |

| PPNR | 2.98±1.35 | 3.42±1.27 | t=2.70**, d=.34 |

| NPNR | 1.99±.93 | 2.76±1.17 | t=5.72***, d=.73 |

| EPDS | 4.90±3.78 | 9.10±5.52 | t=6.95***, d=.89 |

| Suicidal ideation | 6/111; 5.4% | 21/156; 13.5% | χ2=4.63*, RR=2.50 |

|

No SOI n=183/267 |

SOI n=84/267 |

||

| ISI | 9.27±5.49 | 15.14±5.14 | t=8.29***, d=1.10 |

| Sleep latency | 20.88±12.57 | 58.04±29.26 | t=14.50***, d=1.65 |

| Sleep duration | 6.95±1.14 | 5.85±1.46 | t=−6.75***, d=.84 |

| PSAS, Cognitive | 17.24±5.74 | 24.96±7.40 | t=9.24***, d=1.17 |

| PPNR | 3.12±1.33 | 3.49±1.25 | t=2.15*, d=.29 |

| NPNR | 2.23±1.05 | 2.90±1.21 | t=4.61***, d=.59 |

| EPDS | 6.10±4.32 | 10.08±6.14 | t=6.09***, d=.75 |

| Suicidal ideation | 14/183; 7.7% | 13/84; 15.5% | χ2=3.88*, RR=2.01 |

|

No SMI n=81/267 |

SMI n=186/267 |

||

| ISI | 7.21±5.48 | 12.82±5.44 | t=7.72***, d=1.03 |

| Sleep latency | 23.46±17.48 | 36.62±28.05 | t=3.90***, d=.56 |

| Sleep duration | 7.29±1.29 | 6.31±1.26 | t=−5.82***, d=.77 |

| PSAS, Cognitive | 16.22±6.20 | 21.17±7.17 | t=5.39***, d=.74 |

| PPNR | 2.83±1.27 | 3.42±1.30 | t=3.44**, d=.46 |

| NPNR | 1.93±.91 | 2.67±1.17 | t=5.09***, d=.71 |

| EPDS | 5.19±4.13 | 8.30±5.46 | t=4.59***, d=.64 |

| Suicidal ideation | 5/81; 6.2% | 22/186; 11.8% | χ2=1.99, p=.16 |

|

Normal sleep duration n=202/267 |

Short sleep n=65/267 |

||

| ISI | 9.53±5.58 | 16.03±4.54 | t=8.52***, d=1.28 |

| Sleep latency | 26.79±20.44 | 50.62±32.49 | t=6.98***, d=.88 |

| PSAS, Cognitive | 18.63±6.93 | 22.85±7.33 | t=4.21***, d=.59 |

| PPNR | 3.20±1.30 | 3.35±1.36 | t=.82, p=.41 |

| NPNR | 2.38±1.12 | 2.65±1.19 | t=1.67, p=.10 |

| EPDS | 6.70±4.93 | 9.38±5.86 | t=3.64***, d=.49 |

| Suicidal ideation | 15/202; 7.4% | 12/65; 18.5% | χ2=6.59*, RR=2.50 |

|

Non-snorers n=184/265 |

Snorers n=81/265 |

||

| ISI | 10.75±6.15 | 12.03±5.68 | t=1.61, p=.26 |

| Sleep latency | 33.42±27.25 | 31.11±23.25 | t=−0.66, p=.51 |

| Sleep duration | 6.61±1.35 | 6.57±1.36 | t=−0.21, p=.84 |

| PSAS, Cognitive | 19.38±7.24 | 20.30±7.26 | t=0.95, p=.34 |

| PPNR | 3.15±1.32 | 3.43±1.29 | t=1.60, p=.11 |

| NPNR | 2.35±1.13 | 2.65±1.15 | t=2.02*, d=.26 |

| EPDS | 6.95±5.21 | 8.27±5.42 | t=1.88, p=.06 |

| Suicidal ideation | 18/184; 9.8% | 9/81; 11.1% | χ2(1)=0.11, p=.74 |

Note: ISI = insomnia severity index. PSAS, Cognitive = presleep arousal scale, cognitive factor. PPR = positive perinatal nocturnal rumination. NPNR = negative perinatal nocturnal rumination. EPDS = Edinburgh postnatal depression scale.

Pregnant women with insomnia (i.e., ISI ≥ 10, SOI, SMI) reported higher nocturnal rumination and depression and were more likely to endorse suicidal ideation as compared to pregnant women without insomnia (see Table 2 for full results). Importantly, areas of potential specificity were identified. Namely, nocturnal rumination (both general and perinatally focused) was more consistently associated with insomnia than with short sleep or snoring. Suicidal ideation was related to SOI symptoms and short sleep, but not to SMI symptoms or snoring.

Comparing sleep and emotion regulation based on nocturnal rumination, depression, and suicidal ideation.

Next, we compared high vs low nocturnal ruminators on sleep and psychological parameters. As expected, high ruminators as identified by the PSAS-C endorsed higher levels of ruminating on positive and negative thoughts about their pregnancy and their new child when trying to fall asleep (see Table 3 for full results). Additionally, high ruminators reported greater symptom levels of insomnia and depression, shorter sleep duration, and higher rates of suicidal ideation. When comparing those high vs low on positive perinatal-focused nocturnal rumination, high positive ruminators were also elevated on general nocturnal rumination and negative perinatal rumination, but no other group differences were observed. This was starkly different for negative perinatal-focused nocturnal rumination where high negative ruminators endorsed substantially greater insomnia symptoms, general nocturnal rumination, and rates of suicidal ideation, as well as moderately prolonged sleep latency, shorter sleep duration, and moderately higher positive perinatal rumination.

Table 3.

Comparing sleep and psychological characteristics based on nocturnal rumination, depression status, and suicidal ideation.

| Low rumination n=133/265 |

High rumination n=132/265 |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| ISI | 8.21±5.06 | 14.10±5.48 | t=9.09***, d=1.12 |

| Sleep latency | 23.26±17.50 | 42.16±29.63 | t=6.31***, d=.78 |

| Sleep duration | 6.89±1.19 | 6.33±1.45 | t=−3.27**, d=.42 |

| PPNR | 2.99±1.34 | 3.48±1.25 | t=3.09**, d=.38 |

| NPNR | 2.02±.90 | 2.87±1.21 | t=6.56***, d=.80 |

| EPDS | 4.84±3.81 | 9.89±5.40 | t=8.79***, d=1.08 |

| Suicidal ideation | 7/133; 5.3% | 20/132; 15.2% | χ2=7.08**, RR=2.87 |

|

Low PPNR n=140/265 |

High PPNR n=125/140 |

||

| ISI | 10.71±6.10 | 11.63±5.95 | t=1.25, p=.26 |

| Sleep latency | 30.25±24.80 | 35.48±27.26 | t=1.63, p=.10 |

| Sleep duration | 6.67±1.33 | 6.52±1.36 | t=−.87, p=.39 |

| PSAS, Cognitive | 18.33±7.00 | 21.15±7.25 | t=3.22**, d=.40 |

| NPNR | 2.24±1.09 | 2.66±1.17 | t=, 3.04**, d=.37 |

| EPDS | 6.99±5.20 | 7.76±5.41 | t=1.18, p=.24 |

| Suicidal ideation | 13/140; 9.3% | 14/125; 11.2% | χ2=.26, p=.61 |

|

Low NPNR n=152/265 |

High NPNR n=113 |

||

| ISI | 9.21±5.79 | 13.73±5.36 | t=6.48***, d=1.22 |

| Sleep latency | 27.34±23.47 | 40.00±27.70 | t=4.01***, d=.49 |

| Sleep duration | 6.82±1.36 | 6.30±1.27 | t=−3.17**, d=.40 |

| PSAS, Cognitive | 17.07±6.49 | 23.15±6.75 | t=−7.42***, d=.92 |

| PPNR | 2.95±1.35 | 3.62±1.18 | t=4.19***, d=.53 |

| Suicidal ideation | 6/152; 5.3% | 21/113; 18.6% | χ2=15.17***, RR=3.51 |

|

No depression n=224/267 |

Depression n=43/267 |

||

| ISI | 10.06±5.61 | 16.60±5.12 | t=7.10***, d=1.22 |

| Sleep latency | 29.30±23.80 | 49.77±30.14 | t=4.93***, d=.75 |

| Sleep duration | 6.71±1.33 | 6.04±1.31 | t=−3.08**, d=.51 |

| PSAS, Cognitive | 18.06±6.28 | 27.93±6.22 | t=9.44***, d=1.58 |

| PPNR | 3.17±1.33 | 3.58±1.22 | t=1.88, p=.06 |

| NPNR | 2.24±1.09 | 2.66±1.17 | t=6.41***, d=1.02 |

| Suicidal ideation | 14/224; 6.3% | 1¾3; 30.2% | χ2=22.83***, RR=4.79 |

|

No suicidality n=240/267 |

Suicidal Ideation n=27/267 |

||

| ISI | 10.64±5.85 | 15.37±6.01 | t=3.98***, d=.80 |

| Sleep latency | 32.18±26.16 | 36.48±24.61 | t=0.82, p=.42 |

| Sleep duration | 6.67±1.33 | 6.04±1.41 | t=−2.33*, d=.86 |

| PSAS, Cognitive | 19.07±7.05 | 24.85±6.99 | t=4.04***, d=.82 |

| PPNR | 3.23±1.33 | 3.30±1.20 | t=.24, p=.81 |

| NPNR | 2.35±1.12 | 3.26±1.06 | t=4.03***, d=.83 |

| EPDS | 6.60±4.70 | 14.11±5.50 | t=7.74***, d=1.47 |

Note: ISI = insomnia severity index. PSAS, Cognitive = presleep arousal scale, cognitive factor. PPR = positive perinatal nocturnal rumination. NPNR = negative perinatal nocturnal rumination. EPDS = Edinburgh postnatal depression scale.

When comparing depressed vs non-depressed pregnant women, we observed a highly similar pattern of outcomes to those associated with high vs low rumination (both in significance and magnitude of findings), except that depressed and non-depressed women did not differ on levels of positive perinatal nocturnal rumination. Comparing suicidal vs non-suicidal pregnant women yielded similar results in terms of insomnia, sleep duration, broadly focused rumination, and negative perinatal rumination, except that both sleep latency and positive perinatal nocturnal rumination did not differ between groups.

Specificity among insomnia, rumination, depression, and suicidal ideation.

We next assessed patterns of specificity among insomnia, rumination, depression, and suicidal ideation. Specifically, we ran four multivariate logistic regression models predicting nocturnal rumination (high vs low), insomnia status, depression status, and suicidal ideation as predicted by sleep symptoms, rumination, depression, and suicidal ideation (controlling for poverty, Medicaid coverage, race, and obesity) identified in Supplementary Table 2. In predicting high rumination, we found that having insomnia (OR=1.88), SOI symptoms (OR=3.98), depression (OR=6.45), and negative perinatal nocturnal rumination (OR=2.06) were all independently associated with elevated odds of having high nocturnal rumination (Table 4). In predicting insomnia, short sleep (OR=20.83), general nocturnal rumination (OR=5.46), and negative perinatal-focused nocturnal rumination (OR=3.11) were significant independent predictors (Table 4).

Table 4.

Multivariate logistic regression models predicting high rumination, positive depression status, and suicidal ideation.

| Outcome | Predictors | b | OR (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSAS-C > 18 | ||||

| χ2=98.99, p<.001 | Poverty | .33 | -- | .44 |

| ISI ≥ 10 | .63 | 1.88 (1.33, 2.65) | <.001 | |

| SOI | 1.38 | 3.98 (1.85, 8.59) | <.001 | |

| SMI | −.02 | -- | .95 | |

| TST<6 | −.25 | -- | .55 | |

| PPNR > 3 | .41 | -- | .19 | |

| NPNR > 2 | .73 | 2.06 (1.08, 3.93) | .03 | |

| EPDS ≥ 13 | 1.86 | 6.45 (1.73, 23.99) | <.01 | |

| Suicidal ideation | .01 | -- | .99 | |

| ISI ≥ 10 | ||||

| χ2=95.30, p<.001 | Poverty | −.20 | -- | .74 |

| Race | .52 | -- | .25 | |

| BMI ≥ 35 | −.72 | -- | .16 | |

| TST<6 | 3.04 | 20.83 (5.34, 81.25) | <.001 | |

| PSAS-C > 18 | 1.70 | 5.46 (2.53, 11.77) | <.001 | |

| PPNR > 3 | −.35 | -- | .37 | |

| NPNR > 2 | 1.13 | 3.11 (1.43, 6.76) | <.01 | |

| Suicidal ideation | 1.24 | -- | .15 | |

| EPDS ≥ 13 | ||||

| χ2=63.48, p<.001 | Poverty | .72 | -- | .13 |

| ISI ≥ 10 | .38 | -- | .25 | |

| SOI | 1.03 | 2.80 (1.13, 6.95) | .03 | |

| SMI | 1.91 | 6.72 (1.15, 39.20) | .03 | |

| TST<6 | −.08 | -- | .86 | |

| PSAS-C > 18 | 1.87 | 6.50 (1.78, 23.73) | <.01 | |

| PPNR > 3 | .06 | -- | .89 | |

| NPNR > 2 | .99 | 2.70 (1.04, 6.98) | .04 | |

| Suicidal ideation | 1.33 | 3.79 (1.22, 11.81) | .02 | |

| Suicidal ideation | ||||

| χ2=31.73, p<.001 | Medicaid | .82 | -- | .08 |

| BMI ≥ 35 | 1.07 | 2.90 (1.09, 7.72) | .03 | |

| ISI ≥ 10 | .11 | -- | .87 | |

| SOI | −.64 | -- | .28 | |

| SMI | −.14 | -- | .83 | |

| TST<6 | .66 | -- | .22 | |

| PSAS-C > 18 | .49 | -- | .42 | |

| PPNR > 3 | −.16 | -- | .85 | |

| NPNR > 2 | 1.25 | 3.50 (1.18, 10.38) | .02 | |

| EPDS ≥ 13 | 1.29 | 3.64 (1.14, 11.61) | .03 |

Note: ISI = insomnia severity index. PSAS, Cognitive = presleep arousal scale, cognitive factor. PPR = positive perinatal nocturnal rumination. NPNR = negative perinatal nocturnal rumination. EPDS = Edinburgh postnatal depression scale.

In a similar multivariate model, we predicted the odds of screening positive for major depression during pregnancy (i.e., EPDS ≥ 13; see Table 4 for full results). Analyses revealed that pregnant women with SOI symptoms (OR=2.80), SMI symptoms (OR=6.72), high rumination (OR=6.50), and high negative perinatal nocturnal rumination (OR=2.70) were at elevated odds of screening positive for prenatal depression. When estimating the odds of endorsing suicidal ideation, we found that obesity (OR=2.90), depression (OR=3.50), and high negative perinatal nocturnal rumination (OR=3.64) were associated with endorsing suicidal ideation (Table 4).

Depression and suicidal ideation rates by insomnia with rumination and insomnia with short sleep

Our last set of analyses evaluated whether odds of endorsing depression/suicidality is augmented by high rumination and short sleep among pregnant women with insomnia. But first, we estimated odds for endorsing major depression and suicidal ideation based on insomnia classification only (see Table 5 for full results). Logistic regression results showed that insomniacs, relative to those without insomnia, were at higher odds of endorsing depression (OR=8.92; 25.0% vs 3.6% depressed) and suicidal ideation (OR=2.72; 13.5% vs 5.4% suicidal).

Table 5.

Dummy coded logistic regression models regressing depression status and suicidal ideation onto insomnia, rumination, and short sleep.

| Outcome | Predictors | b | OR (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimating depression status and suicidal ideation as predicted by insomnia status only | ||||

| EPDS ≥ 13 | ||||

| χ2=25.82, p<.001 | Good sleepers | -- | -- | -- |

| Insomniacs | 2.19 | 8.92 (3.08, 25.79) | <.001 | |

| Suicidal ideation | ||||

| χ2=4.97, p=.03 | Good sleepers | -- | -- | -- |

| Insomniacs | 1.00 | 2.72 (1.06, 6.99) | .04 | |

| Estimating depression status and suicidality as predicted by insomnia and broad nocturnal rumination | ||||

| EPDS ≥ 13 | ||||

| χ2=53.52, p<.001 | Low ruminating good sleepers | -- | -- | -- |

| High ruminating good sleepers | 2.30 | -- | .05 | |

| Low ruminating insomniacs | 1.22 | -- | .32 | |

| High ruminating insomniacs | 3.83 | 45.84 (6.13, 342.84) | <.001 | |

| Suicidal ideation | ||||

| χ2=9.69, p=.02 | Low ruminating good sleepers | -- | -- | -- |

| High ruminating good sleepers | .43 | -- | .63 | |

| Low ruminating insomniacs | .22 | -- | .78 | |

| High ruminating insomniacs | 1.43 | 4.19 (1.36, 12.90) | .01 | |

| Estimating depression status and suicidality predicted by insomnia and negative perinatal rumination | ||||

| EPDS ≥ 13 | ||||

| χ2=42.46, p<.001 | Low ruminating good sleepers | -- | -- | -- |

| High ruminating good sleepers | 1.23 | -- | .23 | |

| Low ruminating insomniacs | 1.55 | -- | .06 | |

| High ruminating insomniacs | 3.17 | 23.86 (5.49, 103.63) | <.001 | |

| Suicidal ideation | ||||

| χ2=9.69, p=.02 | Low ruminating good sleepers | -- | -- | -- |

| High ruminating good sleepers | 2.01 | 7.46 (1.28, 43.39) | .03 | |

| Low ruminating insomniacs | .94 | -- | .29 | |

| High ruminating insomniacs | 2.30 | 9.96 (2.22, 44.60) | <.01 | |

| Estimating depression status and suicidal ideation as predicted by insomnia and short sleep | ||||

| EPDS ≥ 13 | ||||

| χ2=53.52, p<.001 | No insomnia, normal sleep duration | -- | -- | -- |

| No insomnia, short sleep | −17.95 | -- | .99 | |

| Insomnia, normal sleep duration | 1.99 | 7.31 (2.41, 22.18) | <.001 | |

| Insomnia, short sleep | 2.38 | 10.78 (3.45, 33.72) | <.001 | |

| Suicidal ideation | ||||

| χ2=9.69, p=.02 | No insomnia, normal sleep duration | -- | -- | -- |

| No insomnia, short sleep | 1.92 | -- | .12 | |

| Insomnia, normal sleep duration | .88 | -- | .12 | |

| Insomnia, short sleep | 1.50 | 4.49 (1.48, 13.62) | ||

Note: EPDS = Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. Suicidal ideation = positive response on EPDS item #10. Insomnia measured by the Insomnia Severity Scale. Broad nocturnal rumination measured by the Pre-Sleep Arousal Scale Cognitive factor. Short sleep is < 6 hrs per night as reported on item 4A on the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. b = beta. OR = odds ratio. 95% CI = 95% confidence interval for the OR. χ2 = Chi-square for model fit with significant values indicating superiority to a null model. p = significance value.

Next, we ran a series of logistic regression models estimating our two primary clinical outcomes: depression status and suicidal ideation. The first pair of dummy coded logistic regression models compared odds of depression/suicidality for (1) high ruminators with good sleep, (2) low ruminators with insomnia, and (3) high ruminators with insomnia to (4) the reference group low ruminators good sleep (Table 5). Notably, high vs low rumination here was operationalized based on the median split for the PSAS-C. The only group shown to be at greater odds of depression and/or suicidality were high ruminators with insomnia, thereby suggesting that the odds of reporting clinical depression and suicidal ideation is highest among those with insomnia and high rumination, whereas pregnant women with insomnia or high rumination alone do not differ in odds of endorsing depression or suicidality relative to pregnant women with low rumination and good sleep. Important to emphasize here is that 35.6% of highly ruminating insomniacs screened positive for depression and 17.3% endorsed suicidal ideation; see depression and suicidal ideation rates for all groups in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Percentage rates of depression and suicidal ideation based on insomnia status and broadly focused nocturnal rumination.

We then re-ran these same analyses, but focusing specifically on negative perinatal-focused nocturnal rumination; i.e., instead of categorizing high/low rumination on the full PSAS-C, here it was based on the median split for our single negative perinatal rumination item. Results were remarkably similar for depression such that only pregnant women with insomnia and high negative perinatal rumination were at elevated odds of endorsing depression (OR=23.86, see Table 5). Regarding suicidal ideation, high negative perinatal ruminators were at elevated odds of endorsing suicidal ideation including ruminators with insomnia (OR=9.96) and those without insomnia (OR=7.46; Table 5). Indeed, a posthoc logistic regression showed that high negative perinatal ruminators with insomnia were not at greater odds of endorsing suicidal ideation than those without insomnia (OR=1.34, 95% CI=.41, 4.39, p=.63). See rates of depression and suicidal ideation in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Percentage rates of depression and suicidal ideation based on insomnia status and negative perinatal-focused nocturnal rumination.

Finally, we ran a third pair of dummy coded logistic regression models that compared odds of depression/suicidality for (1) non-insomniacs with short sleep, (2) insomniacs with normal sleep duration, and (3) short sleeping insomniacs to (4) the reference group good sleepers with normal sleep duration (Table 5). In estimating depression status, both insomniacs with normal sleep duration (OR=7.31; 22.1% depressed) and short sleeping insomniacs (OR=10.78; 29.5% depressed) were more likely to screen positive for depression than good sleepers with normal sleep duration (3.7% depressed). A posthoc logistic regression comparing odds of depression between insomniacs with vs without short sleep yielded no group difference (b=.39, OR=1.48, 95% CI=.71 – 3.07, p=.30). In estimating suicidal ideation, only short sleeping insomniacs were at greater odds of endorsing suicidal ideation compared to good sleepers with normal sleep duration (OR=4.49; 18.0% vs 4.7% suicidal), whereas neither short sleep nor insomnia alone conferred increased odds of suicidal ideation.

DISCUSSION

In a sample of 267 women, problematic sleep, nocturnal rumination, depression, and suicidal ideation were all highly endorsed in mid and late pregnancy. Consistent with prior works on prenatal sleep,4,5 rates of insomnia and short sleep far exceeded those found in the broader adult population.7,57,58 Similarly, depression and suicidal ideation rates were higher than prevalence estimates for US adults,59,60 and similar to or even higher than those reported by pregnant women in other studies.4,34 Highly ruminative women in our study reported high levels of sleep onset insomnia symptoms and depressive symptoms, and ruminating on perinatal concerns was strongly associated with depression and suicidal ideation. Depression and suicidal ideation rates were highest in our study for pregnant women with both insomnia and high rumination.

Insomnia, depression, and suicidal ideation in pregnancy

Sleep onset insomnia symptoms (which are closely tied to stress as shown here and in prior studies6,19,61) and sleep maintenance insomnia symptoms (which are closely tied to pregnancy-related discomfort6) both independently corresponded to prenatal depression. Rates of depression and suicidal ideation were markedly higher among pregnant women with insomnia as compared to those without insomnia. This is consistent with a burgeoning literature describing the high co-occurrence between insomnia and psychiatric illness during pregnancy.4,5,12,34 Although the relationship between insomnia and depression in the general adult population is bidirectional, some evidence suggests that the effects of sleep on mood are larger than vice versa.13,62–64 Moreover, insomnia is a robust predictor of future depression, precedes nearly half of new depression cases, and is the residual symptom most strongly associated with depression relapse.65–68 Thus, when interpreting our findings within this context, non-depressed pregnant women with clinical insomnia may be at high risk for depression incidence or relapse in the perinatal period. If future prospective studies support insomnia as a prognostic marker for perinatal depression, then interventions targeting insomnia as an active prodrome to prevent perinatal depression carries important potential to improve maternal and fetal/infant health.

Regarding suicidal thoughts and behaviors, pregnant women with insomnia were more likely to endorse suicidal thoughts than good sleepers. However, data from our adjusted model estimating suicidal ideation suggest that insomnia itself may not be directly linked to suicidal thoughts and behaviors, per se’, but rather linked via emotion dysregulation and depression. The extant literature offers mixed results regarding whether insomnia directly or indirectly (via depression or depressogenic behaviors) corresponds to suicidal thoughts and behaviors.69–71 In a previous investigation of pregnant women, our team found that insomnia symptoms were independently associated with suicidal ideation, even when controlling for depression. Yet, data from the present study suggest a potential indirect link between insomnia and suicidal ideation during pregnancy. Notably, both studies were cross-sectional and we presently lack the prospective data necessary test a mediation model. Future research should explore the extent to which suicidal ideation in pregnant women with insomnia may be accounted for by higher levels of emotion dysregulation such as rumination.

Nocturnal rumination in prenatal insomnia and depression

Rumination plays an important role in the etiology and maintenance of depression in the general adult population28,72 and contributes to the greater depression burden for women.73 Only recently has rumination begun to garner scientific interest in the genesis of perinatal depression.22 Novel to this study is consideration of perinatal women ruminating specifically on their pregnancies and/or new infants. Specifically, we looked at three content areas for rumination when trying to fall asleep: (1) broad nocturnal rumination as measured by the PSAS-C (e.g., concerns about falling asleep, pondering events of the day, feeling mentally alert, having racing thoughts), (2) positive perinatal-focused nocturnal rumination (perseverating on positive thoughts about pregnancy or new infant), and (3) negative perinatal-focused nocturnal rumination (worrying or distressing thoughts about pregnancy or new infant). Regarding broad nocturnal rumination, women in our study reported levels similar to those reported by patients with insomnia, psychiatric illness, and chronic pain.50–53,74 This suggests that many women in mid and late pregnancy struggle to regulate their emotional responses to stress.

Pregnant women with insomnia reported even higher levels of nocturnal rumination than insomnia patients from the broader adult population,51 but similar levels reported by patients with clinically severe insomnia symptoms74 and by non-pregnant women with insomnia disorder.32 Broadly focused nocturnal rumination and negative perinatal-specific nocturnal rumination were each independently related to insomnia and to depression. Notably, nocturnal rumination was more robustly associated with sleep onset insomnia than with sleep maintenance issues, which is consistent with stress-related rumination producing prolonged sleep latency.75 Regarding perinatal concerns, our findings are consistent with prior evidence that pregnant women endorse high levels of fear about pregnancy, childbirth, and motherhood, and that these concerns are associated with clinical depression and anxiety in the perinatal period.29 Although data from the present study are cross-sectional, we can consider these results within the context of extant prospective data from the general adult population. Prospective epidemiological data in pregnant and non-pregnant samples have suggested that emotion dysregulation may mediate the effects of insomnia on future depression development.14,76

Prenatal depression rates in the present study were highest among pregnant women with insomnia and high rumination (36–37%) as compared to those without insomnia or rumination (1–2%), rumination alone (8–11%), and insomnia alone (4–10%). Importantly, these patterns were observed for both broadly focused nocturnal rumination and for negative perinatal-focused nocturnal rumination. These findings are similar to a large-scale prospective study we conducted in 1126 initially non-depressed adults from the broader population. Specifically, we previously found that highly ruminative insomniacs were about 2–3 times more likely to develop depression in the 2 years after exposure to major life stress as compared to those with no insomnia and low rumination, high rumination alone, and insomnia alone.30 Taken together, pregnancy and postpartum represent periods of high stress, and women sleeping poorly and having difficulty coping with stress are commonly afflicted with depression during these times. Consideration in perinatal research should be given to ruminative coping as a potential mechanism in the progression from insomnia to perinatal depression.

Nocturnal rumination in prenatal insomnia and suicidal ideation

Suicidality has been linked to rumination77–79 and insomnia69–71,80,81 in the general adult population. Thus, given that insomnia and rumination levels are high in late pregnancy, it is perhaps unsurprising that the suicidal ideation rates reported by pregnant women in our study (10%) and in a previous study by our team34 (10%) are nearly three times the rate endorsed by adults in the US regarding suicidal thoughts and behaviors within the past year (3.7%).60

Patterns of associations among insomnia, rumination, and suicidal ideation were similar to those with depression, but with some notable exceptions. While suicidal ideation was elevated among insomniacs, this relationship became non-significant when accounting for depression. This is consistent with several studies suggesting that depression may account for the suicidogenecity of insomnia.69–71 By comparison, negative perinatal-focused rumination was independently and strongly associated with suicidal ideation, irrespective of insomnia. Indeed, 15–20% of high perinatal ruminators (with or without insomnia) endorsed suicidal ideation compared to just 2% of good sleepers and 6% of insomniacs with low perinatal rumination. And although broadly focused nocturnal rumination was not directly associated with suicidal ideation, preliminary evidence suggested that broad nocturnal rumination may be associated with greater suicidal ideation within the context of insomnia. Highly ruminative insomniacs reported the higher rates of prenatal suicidal ideation (17%) when compared to non-ruminating good sleepers (5%), whereas ruminating good sleepers (7%) and non-ruminative insomniacs (6%). Prospective data on the co-evolution of insomnia, rumination, and suicidal ideation are lacking in both the general adult population and among pregnant women. Clarifying these associations will reveal the degree to which rumination augments risk of developing suicidal thoughts and behaviors among those with insomnia.

Important to emphasize here is that broadly focused nocturnal rumination was not independently related to suicidal ideation when controlling for depression, sleep symptoms, and perinatal-focused rumination. Rather, perinatal-focused rumination—in the form of ruminating on stressful thoughts about pregnancy and/or the new infant—was independently and robustly associated with suicidal ideation. The odds of endorsing suicidal thoughts were 3–4-fold greater for women negatively ruminating about their pregnancy and new infant, relative to non-ruminators, even while controlling for depression, sleep symptoms, and other forms of nocturnal rumination. Taken together, these data indicate that high nocturnal rumination, particularly when perseverating on pregnancy- and new infant-related concerns, may play a critical role in risk for depression development and suicidal thoughts/behaviors in pregnant women.

Short sleep in prenatal insomnia, depression, and suicidal ideation

Nearly a quarter of women in our study endorsed short nightly sleep, and these short sleepers reported more depressive symptoms and higher rates of suicidal ideation than pregnant women with normal sleep duration. But when controlling for insomnia symptoms and rumination, sleep duration was no longer associated with either depression or suicidal ideation. Although it appears that short sleep may not have a direct association with prenatal depression or suicidal ideation, we observed preliminary evidence that short sleep may potentially augment risk for suicidal ideation among pregnant women with insomnia.

Short sleep insomnia is the most biologically severe phenotype of the disorder such that the synergistic effects of insomnia symptoms and short sleep duration have widespread and severe negative health consequences.36 Although sleep duration is best defined via objective assessment, studies relying on self-reported sleep duration have shown that comorbidities are at their most prolific when insomnia symptoms/sleep disturbance are combined with short sleep.45,62,82,83 However, we are unaware of prior studies looking at the independent and combined effects of insomnia and short sleep in pregnant women. We found that the odds of endorsing depression were elevated among insomniacs relative to good sleepers, but that odds for depression did not differ between insomniacs with short vs normal sleep duration. This is contrary to prior findings regarding depression-risk in relation to insomnia and short sleep.45,62 Notably, we would like to caution against over-interpreting this result as prior research has shown that objectively-measured sleep duration yields more reliable results regarding the combined effects of insomnia and short sleep on negative health outcomes.36

More in-line with the extant literature on short sleep insomnia, short sleeping insomniacs were at highest odds of endorsing suicidal ideation, whereas those with insomnia or short sleep alone did not differ from good sleepers with normal sleep duration. These preliminary results suggest that short sleep may augment suicidality-risk among pregnant women with insomnia. However, prospective data using objective sleep measurements (polysomnography or actigraphy) are needed to clarify the associations among insomnia, short sleep, depression, and suicidal ideation during pregnancy.

Disparities in sleep and emotion regulation in regard to poverty, race, and obesity.

While not the primary focus of the investigation, we identified a number of disparities in sleep and emotion regulation parameters that warrant acknowledgement given that these are important contextual factors in understanding risk in this patient population. Regarding sleep symptoms, women in poverty reported elevated insomnia symptoms, whereas non-Hispanic black women and obese women reported both elevated insomnia and shorter sleep duration. For more details on sleep disparities in this sample, please refer to Kalmbach et al.38 Regarding rumination, women in poverty endorsed moderately higher levels of broadly focused nocturnal rumination than those above the poverty line. Depression levels and suicidal ideation rates were higher for pregnant women in poverty and for those with Medicaid insurance coverage. Obesity was also associated with higher rates of suicidal ideation. These results identify that pregnant women in poverty and who are obese may be at elevated risk for these health complications during pregnancy and may warrant closer monitoring during routine prenatal care. Notably, the extent to which these health problems pre-exist vs develop during pregnancy is unclear and should be the focus of future research.

Limitations

Our study findings should be interpreted in the context of methodological limitations. The study was cross-sectional and thus pre-pregnancy health indicators and sleep symptoms are unknown. Data are somewhat mixed regarding whether sleep quality changes drastically across pregnancy,2,5,11,84,85 therefore we cannot determine the extent to which high rates of sleep disturbance in our sample represent changes from pre-pregnancy baseline. Further, we cannot establish directionality among rumination, insomnia, and depression. Rather, we considered these findings within the context of prior investigations in non-pregnant samples, but prospective research is needed in women in the perinatal period. Another important limitation is the absence of a more general rumination measure. Although nocturnal rumination is clearly associated with both insomnia and depression in this population, it remains unclear as to whether daytime vs nocturnal rumination is differentially related to perinatal symptoms of insomnia or depression. Prospective research accounting for both daytime and nocturnal rumination is needed to clarify these temporal associations and explore potential specificity regarding the timing of rumination.

Only women identifying as non-Hispanic white and non-Hispanic black were well represented in this study, thus limiting generalizability to women outside of these racial groups. By extension, we only compared these two racial groups when exploring health disparities. Thus, race-related differences pertaining to Hispanic, Latinx, Asian, and other groups were not explored. Lastly, all sleep data were self-reported. While patient impressions of their sleep are important, subjective reports on sleep duration and sleep breathing issues can be inconsistent with objective data via sleep laboratory, wearable technology, and partner reports. When possible, future research should consider using objective sleep assessments and partner reports of sleep and sleep disordered breathing symptoms. Similarly, healthcare providers may seek partner input on patient sleep (e.g., to determine snoring) when available and appropriate.

Conclusions

Women in mid-to-late pregnancy endorse alarmingly high levels of insomnia, nocturnal rumination, depression, and suicidal ideation. Sociodemographic factors associated with higher rates of these pregnancy complications include income-based poverty, Medicaid insurance coverage, self-identifying as non-Hispanic black, and obesity. Rates of clinical depression and suicidal ideation are highest for pregnant women with clinical levels of insomnia and high rumination. The content of rumination may play an important role in disease-risk as pregnant women who ruminate specifically about their pregnancy and/or new infant have substantially higher rates of depression and suicidal ideation than expectant mothers who do not ruminate on perinatal concerns. Interpretation of these results in the context of the extant literature suggests that, even among the initially non-depressed, women involved in regular prenatal care with an obstetrician or midwife should be assessed throughout pregnancy for signs of insomnia, difficulty managing mental stress, and excessive concern regarding their pregnancy or new infant as these may be risk factors or early signs of perinatal depression and suicidal ideation. These data extend the literature by highlighting the close associations among insomnia, rumination, and these disease processes evolve during and after pregnancy.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Depression and suicidal ideation rates exceed those in the general population

Over half of women in mid-late pregnancy have clinically significant insomnia

Nocturnal rumination levels in mid and late pregnancy are pathologically high

Ruminators with insomnia have highest rates of depression and suicidality

Perinatal-focused rumination is strongly related to depression and suicidality

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (PI: Kalmbach). Dr. Cheng’s effort was funded by the National Heart, Lung, & Blood Institute (K23 HL13866, PI: Cheng).

Footnotes

Institution where work was performed: Henry Ford Health System.

Declarations: Dr. Kalmbach has received research support from Merck & Co. Dr. Roth. has received research support from Aventis, Cephalon, Glaxo Smith Kline, Neurocrine, Pfizer, Sanofi, Schering-Plough, Sepracor, Somaxon, Syrex, Takeda, TransOral, Wyeth and Xenoport and has acted as a consultant for Abbott, Acadia, Acoglix, Actelion, Alchemers, Alza, Ancil, Arena, Astra Zeneca, Aventis, AVER, BMS, BTG, Cephalon, Cypress, Dove, Elan, Eli Lilly, Evotec, Forest, Glaxo Smith Kline, Hypnion, Impax, Intec, Intra-Cellular, Jazz, Johnson & Johnson, King, Lundbeck, McNeil, Medici Nova, Merck & Co., Neurim, Neurocrine, Neurogen, Novartis, Orexo, Organon, Prestwick, Procter-Gamble, Pfizer, Purdue, Resteva, Roche, Sanofi, Schering-Plough, Sepracor, Servier, Shire, Somaxon, Syrex, Takeda, TransOral, Vanda, Vivometrics, Wyeth, Yamanuchi, and Xenoport. Dr. Drake has received research support from Merck & Co., Eisai Co., Aladdin Dreamer, Jazz, Actelion, and Teva; and has served on speakers bureau for Merck & Co. No other financial or non-financial interests exist.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Geller PA. Pregnancy as a stressful life event. CNS spectrums. 2004;9(3):188–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mindell JA, Cook RA, Nikolovski J. Sleep patterns and sleep disturbances across pregnancy. Sleep medicine. 2015;16(4):483–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bennett HA, Einarson A, Taddio A, Koren G, Einarson TR. Prevalence of depression during pregnancy: systematic review. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2004;103(4):698–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D⊘rheim SK, Bjorvatn Br, M Eberhard-Gran. Insomnia and depressive symptoms in late pregnancy: a population-based study. Behavioral sleep medicine. 2012;10(3):152–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kızılırmak A, Timur S, Kartal B. Insomnia in pregnancy and factors related to insomnia. The Scientific World Journal. 2012;2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Kalmbach DA, Cheng P, Sangha R, et al. Insomnia, short sleep, and snoring in mid and late pregnancy: Disparities related to poverty, race, and obesity. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Ohayon MM. Epidemiology of insomnia: what we know and what we still need to learn. Sleep medicine reviews. 2002;6(2):97–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morin CM, LeBlanc M, Daley M, Gregoire J, Merette C. Epidemiology of insomnia: prevalence, self-help treatments, consultations, and determinants of help-seeking behaviors. Sleep medicine. 2006;7(2):123–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roth T Insomnia: definition, prevalence, etiology, and consequences. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2007;3(5 Suppl):S7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marcus SM. Depression during pregnancy: rates, risks and consequences. Journal of Population Therapeutics and Clinical Pharmacology. 2009;16(1). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palagini L, Gemignani A, Banti S, Manconi M, Mauri M, Riemann D. Chronic sleep loss during pregnancy as a determinant of stress: impact on pregnancy outcome. Sleep medicine. 2014;15(8):853–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Swanson LM, Pickett SM, Flynn H, Armitage R. Relationships among depression, anxiety, and insomnia symptoms in perinatal women seeking mental health treatment. Journal of Women’s Health. 2011;20(4):553–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baglioni C, Spiegelhalder K, Lombardo C, Riemann D. Sleep and emotions: a focus on insomnia. Sleep medicine reviews. 2010;14(4):227–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Batterham PJ, Glozier N, Christensen H. Sleep disturbance, personality and the onset of depression and anxiety: prospective cohort study. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;46(11):1089–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pillai V, Steenburg LA, Ciesla JA, Roth T, Drake CL. A seven day actigraphy-based study of rumination and sleep disturbance among young adults with depressive symptoms. J Psychosom Res. 2014;77(1):70–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harvey AG. Unwanted Intrusive Thoughts in Insomnia. 2005.

- 17.Harvey AG. A cognitive theory and therapy for chronic insomnia. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2005;19(1):41. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pillai V, Drake CL. Sleep and repetitive thought: the role of rumination and worry in sleep disturbance In: Sleep and affect. London: Elsevier; 2015:201–225. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harvey AG. Pre-sleep cognitive activity: A comparison of sleep-onset insomniacs and good sleepers. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2000;39(3):275–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vafapoor H, Zakiei A, Hatamian P, Bagheri A. Correlation of Sleep Quality with Emotional Regulation and Repetitive Negative Thoughts: A Casual Model in Pregnant Women. Journal of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences. 2018;22(3). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mindell JA, Jacobson BJ. Sleep disturbances during pregnancy. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing. 2000;29(6):590–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DeJong H, Fox E, Stein A. Rumination and postnatal depression: A systematic review and a cognitive model. Behaviour research and therapy. 2016;82:38–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Mahen HA, Flynn HA, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Rumination and interpersonal functioning in perinatal depression. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2010;29(6):646–667. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Just N, Alloy LB. The response styles theory of depression: tests and an extension of the theory. Journal of abnormal psychology. 1997;106(2):221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilkinson PO, Croudace TJ, Goodyer IM. Rumination, anxiety, depressive symptoms and subsequent depression in adolescents at risk for psychopathology: a longitudinal cohort study. BMC psychiatry. 2013;13(1):250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abela JR, Hankin BL. Rumination as a vulnerability factor to depression during the transition from early to middle adolescence: A multiwave longitudinal study. Journal of abnormal psychology. 2011;120(2):259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spasojević J, Alloy LB. Rumination as a common mechanism relating depressive risk factors to depression. Emotion. 2001;1(1):25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nolen-Hoeksema S, Wisco BE, Lyubomirsky S. Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on psychological science. 2008;3(5):400–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martini J, Asselmann E, Einsle F, Strehle J, Wittchen H-U. A prospective-longitudinal study on the association of anxiety disorders prior to pregnancy and pregnancy-and child-related fears. Journal of anxiety disorders. 2016;40:58–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kalmbach DA, Pillai V, Drake CL. Nocturnal insomnia symptoms and stress-induced cognitive intrusions in risk for depression: A 2-year prospective study. PloS one. 2018;13(2):e0192088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taylor DJ. Insomnia and depression. Sleep. 2008;31(4):447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hantsoo L, Khou CS, White CN, Ong JC. Gender and cognitive-emotional factors as predictors of pre-sleep arousal and trait hyperarousal in insomnia. J Psychosom Res. 2013;74(4):283–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gelaye B, Barrios YV, Zhong Q-Y, et al. Association of poor subjective sleep quality with suicidal ideation among pregnant Peruvian women. General hospital psychiatry. 2015;37(5):441–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Palagini L, Cipollone G, Masci I, et al. Stress-related sleep reactivity is associated with insomnia, psychopathology and suicidality in pregnant women: preliminary results. Sleep Medicine. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Woznica AA, Carney CE, Kuo JR, Moss TG. The insomnia and suicide link: toward an enhanced understanding of this relationship. Sleep medicine reviews. 2015;22:37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vgontzas AN, Fernandez-Mendoza J, Liao D, Bixler EO. Insomnia with objective short sleep duration: the most biologically severe phenotype of the disorder. Sleep medicine reviews. 2013;17(4):241–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fernandez-Mendoza J, Shea S, Vgontzas AN, Calhoun SL, Liao D, Bixler EO. Insomnia and incident depression: role of objective sleep duration and natural history. Journal of sleep research. 2015;24(4):390–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cuamatzi-Castelan A, Kalmbach DA, Atkinson R, et al. Insomnia in late pregnancy: Characterizing phenotypes and identifying associated factors. Annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies; 2019; San Antonio. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bastien CH, Vallières A, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep medicine. 2001;2(4):297–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morin CM, Belleville G, Bélanger L, Ivers H. The Insomnia Severity Index: psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response. Sleep. 2011;34(5):601–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF III, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry research. 1989;28(2):193–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fichtenberg NL, Putnam SH, Mann NR, Zafonte RD, Millard AE. Insomnia screening in postacute traumatic brain injury: utility and validity of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation. 2001;80(5):339–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fichtenberg NL, Zafonte RD, Putnam S, Mann NR, Millard AE. Insomnia in a post-acute brain injury sample. Brain Injury. 2002;16(3):197–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kalmbach DA, Conroy DA, Falk H, et al. Poor sleep is linked to impeded recovery from traumatic brain injury. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Kalmbach DA, Pillai V, Arnedt JT, Drake CL. DSM-5 Insomnia and Short Sleep: Comorbidity Landscape and Racial Disparities. Sleep. 2016;39(12):2101–2111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.O’Brien LM, Bullough AS, Owusu JT, et al. Snoring during pregnancy and delivery outcomes: a cohort study. Sleep. 2013;36(11):1625–1632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression: development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. The British journal of psychiatry. 1987;150(6):782–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Matthey S, Henshaw C, Elliott S, Barnett B. Variability in use of cut-off scores and formats on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale–implications for clinical and research practice. Archives of women’s mental health. 2006;9(6):309–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nicassio PM, Mendlowitz DR, Fussell JJ, Petras L. The phenomenology of the pre-sleep state: the development of the pre-sleep arousal scale. Behaviour research and therapy. 1985;23(3):263–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith M, Perlis M, Smith M, Giles D, Carmody T. Sleep quality and presleep arousal in chronic pain. Journal of behavioral medicine. 2000;23(1):1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Morin CM, Rodrigue S, Ivers H. Role of stress, arousal, and coping skills in primary insomnia. Psychosomatic medicine. 2003;65(2):259–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ong JC, Shapiro SL, Manber R. Combining mindfulness meditation with cognitive-behavior therapy for insomnia: a treatment-development study. Behavior therapy. 2008;39(2):171–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Alfano CA, Pina AA, Zerr AA, Villalta IK. Pre-sleep arousal and sleep problems of anxiety-disordered youth. Child Psychiatry & Human Development. 2010;41(2):156–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Grandner MA, Petrov MER, Rattanaumpawan P, Jackson N, Platt A, Patel NP. Sleep symptoms, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic position. Journal of clinical sleep medicine. 2013;9(09):897–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chung F, Abdullah HR, Liao P. STOP-Bang questionnaire: a practical approach to screen for obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 2016;149(3):631–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lichstein K, Durrence H, Taylor D, Bush A, Riedel B. Quantitative criteria for insomnia. Behaviour research and therapy. 2003;41(4):427–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Walch OJ, Cochran A, Forger DB. A global quantification of “normal” sleep schedules using smartphone data. Science advances. 2016;2(5):e1501705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Roth T, Roehrs T. Insomnia: epidemiology, characteristics, and consequences. Clinical cornerstone. 2003;5(3):5–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kessler RC. Epidemiology of women and depression. Journal of affective disorders. 2003;74(1):5–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Crosby A, Gfroerer J, Han B, Ortega L, Parks SE. Suicidal thoughts and behaviors among adults aged≥18 Years--United States, 2008–2009. 2011. [PubMed]

- 61.Kalmbach DA, Anderson JR, Drake CL. The impact of stress on sleep: Pathogenic sleep reactivity as a vulnerability to insomnia and circadian disorders. Journal of Sleep Research. 2018:e12710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.Kalmbach DA, Arnedt JT, Song PX, Guille C, Sen S. Sleep disturbance and short sleep as risk factors for depression and perceived medical errors in first-year residents. Sleep. 2017;40(3):zsw073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kalmbach DA, Fang Y, Arnedt JT, et al. Effects of Sleep, Physical Activity, and Shift Work on Daily Mood: a Prospective Mobile Monitoring Study of Medical Interns. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2018:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64.Johnson EO, Roth T, Breslau N. The association of insomnia with anxiety disorders and depression: exploration of the direction of risk. Journal of psychiatric research. 2006;40(8):700–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Baglioni C, Battagliese G, Feige B, et al. Insomnia as a predictor of depression: a meta-analytic evaluation of longitudinal epidemiological studies. Journal of affective disorders. 2011;135(1):10–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ohayon MM, Roth T. Place of chronic insomnia in the course of depressive and anxiety disorders. Journal of psychiatric research. 2003;37(1):9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Franzen PL, Buysse DJ. Sleep disturbances and depression: risk relationships for subsequent depression and therapeutic implications. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience. 2008;10(4):473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.McClintock SM, Husain MM, Wisniewski SR, et al. Residual symptoms in depressed outpatients who respond by 50% but do not remit to antidepressant medication. Journal of clinical psychopharmacology. 2011;31(2):180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nadorff MR, Nazem S, Fiske A. Insomnia symptoms, nightmares, and suicidal ideation in a college student sample. Sleep. 2011;34(1):93–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nadorff MR, Fiske A, Sperry JA, Petts R, Gregg JJ. Insomnia symptoms, nightmares, and suicidal ideation in older adults. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2012;68(2):145–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cukrowicz KC, Otamendi A, Pinto JV, Bernert RA, Krakow B, Joiner TE Jr. The impact of insomnia and sleep disturbances on depression and suicidality. Dreaming. 2006;16(1):1. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Watkins ER. Constructive and unconstructive repetitive thought. Psychological bulletin. 2008;134(2):163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nolen-Hoeksema S, Larson J, Grayson C. Explaining the gender difference in depressive symptoms. Journal of personality and social psychology. 1999;77(5):1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Puzino K, Frye SS, LaGrotte CA, Vgontzas AN, Fernandez-Mendoza J. Am I (hyper) aroused or anxious? Clinical significance of pre-sleep somatic arousal in young adults. Journal of sleep research. 2019:e12829. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 75.Zoccola PM, Dickerson SS, Lam S. Rumination predicts longer sleep onset latency after an acute psychosocial stressor. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2009;71(7):771–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Marques M, Bos S, Soares MJ, et al. Is insomnia in late pregnancy a risk factor for postpartum depression/depressive symptomatology? Psychiatry research. 2011;186(2–3):272–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Morrison R, O’connor RC. A systematic review of the relationship between rumination and suicidality. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2008;38(5):523–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Surrence K, Miranda R, Marroquín BM, Chan S. Brooding and reflective rumination among suicide attempters: Cognitive vulnerability to suicidal ideation. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2009;47(9):803–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chan S, Miranda R, Surrence K. Subtypes of rumination in the relationship between negative life events and suicidal ideation. Archives of Suicide Research. 2009;13(2):123–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.McCall WV, Black CG. The link between suicide and insomnia: theoretical mechanisms. Current psychiatry reports. 2013;15(9):389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Winsper C, Tang NK. Linkages between insomnia and suicidality: prospective associations, high-risk subgroups and possible psychological mechanisms. International review of psychiatry. 2014;26(2):189–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kalmbach DA, Abelson JL, Arnedt JT, Zhao Z, Schubert JR, Sen S. Insomnia symptoms and short sleep predict anxiety and worry in response to stress exposure: a prospective cohort study of medical interns. Sleep medicine. 2019;55:40–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sivertsen B, Pallesen S, Glozier N, et al. Midlife insomnia and subsequent mortality: the Hordaland health study. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Santiago JR, Nolledo MS, Kinzler W, Santiago TV. Sleep and sleep disorders in pregnancy. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2001;134(5):396–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Facco FL, Kramer J, Ho KH, Zee PC, Grobman WA. Sleep disturbances in pregnancy. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2010;115(1):77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.