Abstract

This article presents the effects of a synchronized Latino youth/parent intervention on adolescent inhalant use. The analytic sample included only Latino adolescents (N=487) between the ages of 12 and 14. Randomized at the school-level, the design included three possible conditions: 1) child and parent received the prevention interventions, 2) only the parent received the prevention intervention, 3) neither child or parent received the prevention interventions. Drawing from the ecodevelopmental perspective, the overall hypothesis was that youth randomly assigned to the condition with both interventions will report the strongest inhalant use prevention outcomes. Descriptive statistics and regression tests of significant group differences by treatment condition confirmed the overall hypothesis. Children receiving the youth intervention and whose parents received the synchronized parenting intervention reported the strongest desired inhalant prevention effects. The findings are interpreted from an ecodevelopmental perspective and implications for practice, policy and future research are discussed.

Keywords: Inhalant use, substance use prevention interventions, Latino, adolescents

Latinos are a rapidly growing segment of the U.S. population and currently represent the largest racial-ethnic group in the country (U.S. Census Bureau, 2015). Developmentally, inhalants are typically initiated in preadolescence with inhalant use rates among Latinos being the highest in 8th grade (Johnston et al., 2014). Approximately 5% of White and African American 8th grade students report past year inhalant use, compared to 7.6% of Latinos (Johnston et al., 2014). Despite these high rates, inhalant use is an understudied area of research (Nakawaki & Crano, 2015), particularly as it relates to low-income Latinos in early adolescence.

Adolescent Inhalant Use

Inhalants are legally obtained and often come from household products, such as aerosol propellants, glue, nail polish remover, and gasoline (Weintraub, Gandhi, & Robinson, 2000). They are consumed by way of several methods, including: inhalation of vapors from a bag, breathing through a substance-soaked rag, and snorting or sniffing from a container; the high generally lasts 15 minutes to one hour (Howard et al., 2011). Inhalants are often the first drug to be initiated by youth likely because they are easily accessible in the home, cheap, and legal to purchase and possess (Johnston, O’Malley, Miech, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2015). Accordingly, inhalant use is most prevalent in early adolescence (Johnston et al., 2015), and in many cases is initiated in preadolescence (Scott & Scott, 2013).

A host of detrimental effects accompany adolescent inhalant use. Use of inhalants is associated with poor executive cognitive functioning (Howard et al., 2011) and a diminished ability to process information (Scott & Scott, 2013). Behaviorally, adolescent inhalant use is related to antisocial behavior and mental health challenges (Freedenthal, Vaughn, Jenson, & Howard, 2007; Howard, Perron, Vaughn, Bender, & Garland, 2010). In addition, inhalant use negatively affects physical health given the toxicity of many solvents. Certain substances have been associated with lung, heart, kidney, and liver damage (Weintraub et al., 2000).

Although inhalant use is often experimental and consists of only one or two tries, use of inhalants can become problematic. It is estimated that one fifth of individuals who experiment with inhalants develop an inhalant use disorder characterized by dependence or abuse (Perron, Howard, Maitra, & Vaughn, 2009). The risk of developing a disorder is highest following initial experimentation, and the earlier individuals initiate inhalant use, the more likely they are to abuse or become dependent upon them (Perron et al., 2009). Regardless, even one-time use of inhalants has the potential to yield complications that extend into adulthood and, in some cases, has resulted in “sudden sniffing death” (e.g., Bowen, 2011).

Ecodevelopmental Factors in Adolescent Substance Use

The ecodevelopmental model, which guides the present study, describes sources of risk and protection in adolescents’ lives and their interrelations (Szapocznik & Coatsworth, 1999). This model can be used to understand the factors and processes from a variety of contexts that predispose youth to engage in or abstain from substance use. The environmental context that most directly influences the adolescent is the microsystem. The microsystem involves the immediate contexts in which youth participate, including peer, family, and school environments. Microsystemic influences are highly important to consider as they are posited to have one of the largest impacts on adolescents’ developmental processes (Coatsworth, Pantin, & Szapocznik, 2002). The next environmental system, the mesosystem, pertains to interactions between microsystemic factors, such as parental supervision over peer activities. The exosystem refers to broader factors that exert influence, such as parents’ social support. The macrosystem concerns the social and cultural contexts that confer risk for or protection against substance use, including poverty and discrimination. Finally, the chronosystem refers to life transition and changes over the lifespan and include puberty and educational transitions (Szapocznik & Coatsworth, 1999).

This study specifically highlights the importance of peer and family-related ecodevelopmental factors within the microsystem. Peer and family influences impact substance use by first impacting youth’s anti-drug norms or the extent to which they perceive their networks to disapprove of substance use and, thus, disapprove of use themselves. The actual and perceived use of inhalants by peers increases the risk of engagement with inhalants (Nguyen, O’Brien, & Schapp, 2016; Ober, Miles, Ewing, Tucker, & D’Amico, 2013). As such, drug refusal self-efficacy, or the perceived ability to refuse drug offers in the presence of peers is an important protective factor against inhalant use (Ober et al., 2013).

Many family-related factors also have a bearing on inhalant use. Effective parenting practices, such as parental monitoring, involvement, communication, and attachment are associated with reduced adolescent substance use (Li, Stanton, & Feigelman, 2000; Nonnemaker et al., 2011; Pokhrel, Unger, Wagner, Ritt-Olson, & Sussman, 2008). Additionally, familismo - or the centrality of family that tends to characterize Latino cultures - is associated with reduced risk of substance use, including inhalant initiation (Ober et al., 2013). Conversely, poor family functioning and family problems are risk factors associated with the use of inhalants and other substances (Best et al., 2014; McGarvey, Canterbury, & Waite, 1996).

Adolescent Substance Use Prevention

To reduce inhalant use, it is imperative that prevention efforts address the ecodevelopmental influences of family and peers. Increasing adolescent anti-substance use norms, improving drug refusal self-efficacy through skills training, decreasing inhalant popularity among peers, and strengthening families have all been identified as important approaches for the prevention of adolescent substance use (Ober et al., 2013; Nonnemaker et al., 2011). The current study examines the effects of two synchronized interventions designed to address peer and family-related risk and protective factors in adolescent substance use.

keepin’ it REAL

keepin’ it REAL (kiR) is an adolescent substance use primary prevention intervention recognized by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration as a model program (Schinke, Brounstein, & Gardner, 2002). The intervention targets youth in 7th grade. Inhalant use prevention efforts targeting early adolescents may be most effective given that consumption peaks around the age of 14, as well as the strong influence of peer and family networks during this period (Ober et al., 2013)

kiR is designed to (a) promote drug resistance skills, (b) develop anti-substance use attitudes and norms, and (c) increase positive decision-making and communication skills to aid in the resistance of drug and alcohol use (Marsiglia & Hecht, 2005). It is delivered by teachers in regular school classrooms over a period of 10 weeks, one lesson per week. Through the acronym REAL, the manualized curriculum imparts four drug resistance strategies—refuse, explain, avoid, and leave (see Gosin, Marsiglia, & Hecht, 2003). Adolescents are taught how to: refuse substance offers by simpling declining; explain their disinterest in drugs and alcohol by providing an excuse; avoid a situation where others might offer a substance; and leave a situation where a substance is offered (Marsiglia & Hecht, 2005).

Families Preparing the New Generation

To enhance the effectiveness of kiR, a synchronized parenting curriculum was developed, Families Preparing the New Generation (Familias Preparando la Nueva Generacíon; FPNG). FPNG is guided by the ecodevelopmental framework, which supports strengthening family functioning and positive parenting practices as a way to prevent adolescent substance use (Coatsworth et al., 2002; Szapocznik & Coatsworth, 1999). FPNG is an 8-workshop series developed to (a) help parents reinforce the REAL strategies their adolescents are learning in the classroom; (b) increase family functioning and positive parenting that fosters prosocial adolescent behavior; and (c) promote decision making and communication skills within the entire family. The topics of the sessions include the role of parents, knowing the adolescent’s environment, skills for successful parent-adolescent communication, and how to talk to adolescents about risky behavior. FPNG was developed and tested by researchers in the southwest in close partnership with Latino parents using a community based participatory research methodology (see Parsai, Castro, Marsiglia, Harthun, & Valdez, 2011). FPNG is available in both English and Spanish and is designed to be delivered by trained bi-lingual and bi-cultural community facilitators in the same school as their adolescent.

Program Efficacy

Effects for kiR as a stand-alone intervention have shown to significantly decrease inhalant use over time for Mexican heritage adolescents (Marsiglia, Kulis, Yabiku, Nieri, & Coleman, 2011), and the effects of kiR appear to be the strongest for more acculturated Latino adolescents who report more initial substance use, suggesting those adolescents most at-risk benefit more from kiR (Marsiglia, Kulis, Wagstaff, Elek, & Dran, 2005). Furthermore, when compared to participation in kiR alone, the combination kiR and FPNG has significantly stronger effects for delaying alcohol, tobacco and marijuana initation and for reducing adolescent substance use over time (Marsiglia, Ayers, Baldwin, & Booth, 2016; Williams, Ayers, Baldwin, & Marsiglia, 2016).

Current Study

This current study builds from the prior efficacy trials and investigates, through an effectiveness trial, if the combination of kiR and FPNG can also significantly reduce inhalant use among Latino adolescents. We hypothesized that (1) when adolescents receive kiR in combination with parents participating in FPNG, inhalant use will be significantly lowered over time, when compared to only parental participation in FPNG and to a comparison group. Drawing from the ecodevelopmental framework, we further hypothesize that (2) those adolescents most at-risk in their individual, peer and family microsystems - through weaker anti-drug norms - will show the strongest prevention effects for inhalant use.

Methods

Study Design

This study is a clustered randomized controlled effectiveness trial which tests the impact of kiR and FPNG on adolescent substance use. Data come from longitudinal parent-adolescent dyads (N=533) collected between 2013 and 2015. Participants were recruited from eligible middle schools (N=27); schools that had a large percentage (>60 %) of Latino students, were currently receiving Title 1 funding (i.e. federal funds provided to meet the needs of at-risk and low-income students), and were located within the boundaries of Maricopa County, Arizona. After block randomization, the 27 schools were randomized into three conditions: (1) Parent and Youth (PY) - adolescents received kiR and parents received FPNG; (2) Parent Only (PO) - adolescents received the standard substance use programming at the school and parents received FPNG; and (3) Comparison (C) – adolescents received the standard substance use programming at the school and parents received Realizing the American Dream (RAD), an 8-week program for Latino parents that aims to increase parental engagement in childrens’ education and academic success (Walker, 2016).

The eligible sample included all 7th grade students and their parents. The recruitment and consenting period occurred at the beginning of the fall semester of the adolescent’s 7th grade year. Informed parental consent was obtained by trained study personnel, maintaining compliance with IRB requirements. Because randomization occurred at the school level, parents were advised of the treatment condition prior to consenting. Of the eligible sample in the 27 schools, the consent rates were low (youth=9%; parent=10%). While the youth intervention took place in all the 7th grade classrooms of the schools randomly assigned to receive kiR, only those youth with parental consent and their own adolescent assent completed the surveys.

Sample

This study examines changes in adolescent inhalant use as influenced by the kiR and FPNG interventions. Therefore, the analytic sample includes only adolescents who self-reported a Latino ethnicity (N=487). Because all parents received a curriculum (FPNG or RAD), all W1 surveys for adolescents were administered one week before the start of the parent programming and before kiR was implemented. The immediate post survey, W2, was completed by adolescents in January of their 7th grade year, approximately one month after parents completed their parenting program. The adolescent attrition rate between W1 and W2 was only 4%. All adolescent surveys, available in English or Spanish, were administered by trained research staff, with less than one percent of the students opting for the Spanish language version of the survey. The adolescent surveys included questions on sociodemographic characteristics, acculturation, family and parenting features, and substance use behaviors and attitudes. At the completion of each survey, adolescents received a small incentive (e.g. toy, pencil). The adolescent sample, on average, came from a two-parent household (71.3%), received free lunch at school (91.6%), and was born in the U.S. (81.1%). There were slightly more boys than girls (52.6%). The adolescents reported, on average, they received B’s in school (M=3.08).

Measures

Inhalant Use

Frequency of inhalant use in the past 30 days at W2 was assessed by the question, “How many times have you sniffed glue, spray paint, or other inhalants to get high in the past 30 days?” Responses included (1) none, (2) 1–2 times, (3) 3–5 times, (4) 6–9 times, (5) 10–19 times, (6) 20–39 times, and (7) 40 or more times. This question has previously been used in a Latino adolescent sample and shown to be developmentally appropriate and reliable (Hecht et al., 2003; Johnston, 1989).

Treatment Conditions

There were three randomly assigned treatment conditions in this study: (1) PY; (2) PO; and (3) C. In the PY condition, adolescents received kiR, and parents received FPNG. In the PO condition, adolescents received the standard substance use programming at the school and parents received FPNG, and in the C condition, adolescents received the standard substance use programming at the school and parents received RAD. For this study, the PY group serves as the reference group in order to test if receipt of both a youth and parent intervention are more effective than receiving just a parenting intervention.

Anti-Drug Norms

Three mean scales assessed anti-drug norms: (a) Personal disapproval of substance use (α=.955); (b) Peer disapproval of substance use (α=.957); and (c) Parental disapproval of substance use (α=.972). All scales were coded so that higher responses indicated stronger anti-drug norms. Personal disapproval of substance use was assessed by three questions, “Is it OK for someone your age to… drink alcohol?... smoke cigarettes?...smoke marijuana?” with responses ranging from (1) definitely OK to (4) definitely not OK. Peer disapproval of substance use was measured by asking, “How would your best friend react if you… got drunk?... smoked cigarettes?...smoke marijuana?” Responses were on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from (1) Very cool to (5) Very uncool. Lastly, parental disapproval of substance use was assessed by asking the adolescent, “How angry would your parents be if they found out you… drank alcohol?...smoked cigarettes?...smoked marijuana?” Responses ranged from (1) Not angry at all to (4) Very angry.

Analysis Plan

Descriptive statistics and tests of significant group differences by treatment condition were analyzed in SPSS v.24 (IBM Corp., 2016) using one-way ANOVAs and chi-square tests. All regression analyses were conducted using Mplus v7.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 2015) with full information maximum likelihood parameter estimates with robust standard errors. All regression analyses were stratified by cohort (N=3) and clustered by school (N=27) in conjunction with a complex sampling design to properly correct the standard errors at both the individual-level and cluster-level. In each regression model, the W1 control variables include inhalant use, usual grades in school, gender, two-parent household, born in the US, and receiving free lunch in school. To control for multicollinearity in tests of interactions, personal, peer, and parental anti-drug norms were first mean centered.

Results

Descriptive statistics and significant group differences by treatment condition are presented in Table 1. Overall, inhalant use is extremely low (M=1.09, SD=0.49), with the vast majority of youth in 7th grade reporting no use (~95%). Inhalant use does increase slightly at W2 for the PO and C groups, but decreases for the PY group (PY: M=1.03, SD=0.22). One-way ANOVAs indicate significant group differences in inhalant use at W2 F(2, 454) = 3.85, p=.022, with post hoc comparisons using the Tukey HSD test indicating the PO group has a significantly higher mean of W2 inhalant use than the PY group. Personal disapproval of substance use is strong, with adolescents in all groups ranging between it is “not OK” and “definitely not OK” to use substances. One-way ANOVAs indicate significant group differences in personal disapproval of substance use at W1 F(2, 475) = 4.38, p=.013, with post hoc comparisons using the Tukey HSD test indicating the PY and C groups have significantly stronger personal anti-drug norms than the PO group. No significant differences exist between the PY and C groups. Peer disapproval of substance use is also high, ranging between a peer reaction of “uncool” to “very uncool” if the adolescent used substances, with no significant group differences. Likewise, for all treatment conditions, adolescents report their parents would be “pretty angry” to “very angry” if the adolescent used substances, with no significant group differences. No significant group differences exist between any of the control variables.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Analytic Sample (N=487)

| Treatment Condition |

Significant Group Differencesa. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent and Youth (PY) |

Parent Only (PO) |

Comparison (C) |

|||||

| M (%) | SD | M (%) | SD | M (%) | SD | ||

| Inhalant Use | |||||||

| Inhalant frequency (w1) | 1.11 | 0.53 | 1.11 | 0.60 | 1.06 | 0.31 | |

| Inhalant frequency (w2) | 1.03 | 0.22 | 1.23 | 0.88 | 1.09 | 0.48 | PY < PO* |

| Anti-Drug Norms (w1) | |||||||

| Personal Disapproval of Substance Use | 3.81 | 0.51 | 3.60 | 0.85 | 3.78 | 0.51 | PY, C > PO* |

| Peer Disapproval of Substance Use | 4.26 | 1.04 | 4.32 | 0.94 | 4.32 | 0.91 | |

| Parental Disapproval of Substance Use | 3.70 | 0.82 | 3.63 | 0.87 | 3.71 | 0.75 | |

| Control Variables (w1) | |||||||

| Usual grades in school | 3.12 | 1.60 | 3.05 | 1.41 | 3.08 | 1.40 | |

| Gender-female | (45.0%) | (49.3%) | (48.6%) | ||||

| Two parent household | (71.5%) | (70.9%) | (71.5%) | ||||

| Born in the USA | (81.5%) | (78.2%) | (82.9%) | ||||

| Free lunch in school | (91.0%) | (90.0%) | (93.6%) | ||||

For continuous variables, one-way ANOVA results with post hoc comparisons using Tukey HSD test indicated that the mean scores were significantly different at * p< .05, ** p<.01, or ***p<.001. For categorical variables, chi-square tests indicated that percentages were significantly different at * p< .05, ** p<.01, or ***p<.001.

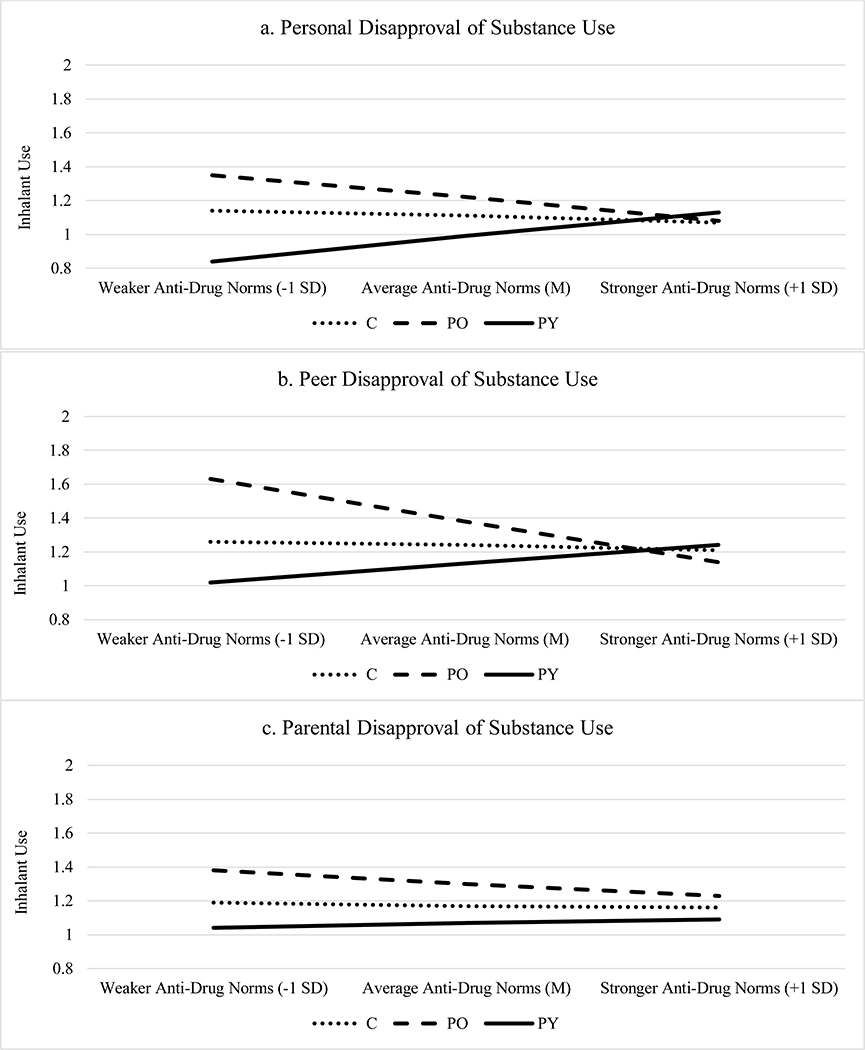

Table 2 presents the standardized estimates of inhalant frequency on receipt of kiR and FPNG as moderated by anti-drug norms after adjustment for the control variables. The interaction effects are graphed in Figure 1. The main effects of treatment condition and personal disapproval of substance use are significant (Model 1) and indicate that the PO and C groups have a significantly higher frequency of inhalant use at W2 compared to the PY group (PO: β=0.17, p<.001; C: β=0.08, p<.01). Having stronger personal anti-drug norms at W1 reduces frequency of inhalant use at W2 (β=−0.08, p<.05). The interactions between personal disapproval of substance use and treatment condition are significant (Model 2). As Figure 1 shows, for adolescents with stronger personal anti-drug norms at W1, frequency of inhalant use at W2 did not vary between the three treatment groups. However, for adolescents that entered the intervention with weaker personal anti-drug norms, those in the PY group showed significantly less inhalant use at W2 compared to those adolescents in the PO and C groups. And, those adolescents in the PY group with weaker personal anti-drug norms showed less frequent inhalant use at W2 than PY adolescents with stronger anti-drug norms. Youth in the PO and C groups with weaker personal anti-drug norms increased their inhalant at W2 compared to their stronger personal anti-drug norm counterparts.

Table 2.

Standardized estimates of inhalant frequency on receipt of keepin’ it REAL and Familias Preparando la Nueva Generacióna.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | |

| Treatment Condition | ||||||||||||

| Parent & Youth (PY - ref) | ||||||||||||

| Parent Only (PO) | 0.17 *** | 0.04 | 0.18 *** | 0.04 | 0.18 *** | 0.04 | 0.20 *** | 0.04 | 0.18 *** | 0.04 | 0.18 *** | 0.04 |

| Comparison (C) | 0.08 ** | 0.03 | 0.10 ** | 0.03 | 0.09 ** | 0.03 | 0.09 ** | 0.03 | 0.09 ** | 0.03 | 0.09 ** | 0.03 |

| Anti-Drug Norms | ||||||||||||

| Personal Disapproval of Substance Use | −0.08 * | 0.04 | 0.25 * | 0.10 | ||||||||

| Peer Disapproval of Substance Use | −0.05 | 0.06 | 0.18 *** | 0.05 | ||||||||

| Parental Disapproval of Substance Use | −0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.03 | ||||||||

| Anti-Drug Norm X PO | −0.34 *** | 0.10 | −0.31 *** | 0.09 | −0.10 | 0.06 | ||||||

| Anti-Drug Norm X C | −0.16 * | 0.08 | −0.12 * | 0.06 | −0.04 | 0.05 | ||||||

All models control for the following w1 variables: Inhalant use, usual grades in school, gender, two-parent household, born in the USA, and receiving free lunch in school.

p< .05, ** p<.01, or ***p<.001.

Figure 1.

Associations between anti-drug norms, treatment condition, and inhalant use among Latino adolescents.

While the main effects of treatment condition remain significant and in the expected direction in Model 3, there is no significant main effect for peer disapproval of substance (β=−0.08, p=0.40). However, the interactions between peer disapproval of substance use and treatment condition are significant (Model 4). A similar pattern emerges for peer disapproval of substance use as seen with personal disapproval of substance use (Figure 1) with no variation by treatment condition in inhalant use at W2 among adolescents with stronger peer anti-drug norms at W1. Like before, the reduction in inhalant frequency is strongest for adolescents in the PY group who began the intervention with weaker peer anti-drug norms. In Model 5, parental disapproval of substance use is not a significant predictor of inhalant use at W2 (β=−0.04, p=0.31), and there is no interaction effect between parental disapproval of substance use by treatment condition (Model 6).

Discussion

These findings support the main and secondary hypotheses of the study. Overall, Latino youth who received kiR at the same time that their parents received FPNG demonstrated the most favorable results regarding inhalant use prevention. Intervening simultaneously with the individual child and her/his parents yielded stronger desirable outcomes for all youth, including those experiencing higher levels of risk at pre-test due to their weaker anti-drug norms at the individual and peer levels. An integrated multilevel intervention seems to be the most efficacious approach in order to effectively prevent inhalant use among Latino adolescents.

These findings are confirmatory of previous results related to youth substance use prevention interventions (Nonnemaker et al., 2011; Hecht et al, 2013). They also advance important new knowledge about inhalant use prevention among Latino youth. Exposing Latino youth to a culturally appropriate prevention intervention at the same time that their parents partake in a complementary parenting program appears to produce the strongest desired prevention effects on the participating youth.

Because Latino preadolescents use inhalants at higher rates than any other ethnic or racial group (Johnston et al., 2014), these findings are important from a public health perspective and can inform the design of culturally specific prevention interventions. From an ecodevelopmental perspective (Szapocznik & Coatsworth, 1999), these findings highlight the importance of intervening at the different areas within the adolescent microsystem. Among Latino youth and in regards to inhalant use, peers and family appear to require special attention. Inhalants are an easily accessible domestic drug and often consumed among peers (Johnston et al., 2015). As demonstrated by this study, prevention interventions can strengthen the positive influences of those domains on individual youth particularly for those most at-risk in the normative and attitudinal levels.

This study supports the important role family can play in promoting the wellbeing of children and youth. Given the power of parents to positively influence their adolescent, as demonstrated by the positive effects of the synchronized interventions presented in this study, family closeness, often called familismo, has the potential to be an asset in youth’s lives. While many Mexican American and other Latino families deal with the stressor of acculturation and acculturation gaps between children and parents (Marsiglia et al., 2005), complicating the parent-child relationship, other Latino families are able to manage the added stressors and provide support and guidance to their preadolescents. Integrated interventions, like the one presented here, appear to be an efficacious way to promote protective family ties that guard against the challenge of youth inhalant use.

From an ecodevelopmental perspective, involving the parents in reducing inhalant use is an effective way to support the already proven efficacious youth-only interventions such as kiR. In fact, the participation rates were slightly higher for the PY condition (12%) that the PO (9%) or C (8%) condition, which may suggest that parents are more likely to participate when their youth is also receiving an intervention. However, these are only short-term results. Future research should examine a longer follow-up period in order to better elucidate the mechanisms that make these synchronized interventions more effective in reducing inhalant use. Additionally, there were no specific anti-inhalant norm questions asked in the surveys; however, research suggests that in general, adolescents who adopt drug-free norms and attitudes will be more likely to abstain from all substances, not just one in particular (Evans, Holtz, White & Snider, 2014). Because this study did not obtain independent validation of substance use, like through urinalysis, there is no way to be certain the changes seen in the PY group are definitive changes in substance use or socially desirable responses because the intervention altered how individuals view their inhalant use behavior. There has been prior documentation of a strong correlation between Latino youth’s self-report of substance and urinalysis results, however (Dillon, Turner, Robbins, & Szapocznik, 2005). Future studies need to include cost-effectiveness and sustainability components. Involving parents and adolescents at the same time can be costly and logistically challenging. Exploring alternative and less costly approaches such as the use of smart phones to implement some of the sessions may be a valid alternative.

Conclusion

This study provided confirmation for developing and implementing synchronized parent and youth substance use prevention interventions in order to reduce inhalant use among Latino adolescents. Having interventions that are culturally-tailored and influence multiple domains of an adolescent’s life – individual, peer, and parent – can influence, shape and alter trajectories of inhalant use. Because parents and peers play an important role in reducing adolescent substance use, these results shed light on how multiple intervention pathways can successfully reduce inhalant use while supporting the unique characteristics of Latino families.

Acknowledgement

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD/NIH), award P20 MD002316 (F. Marsiglia, P.I.)

References

- Best DW, Wilson AS, MacLean S, Savic M, Reed M, Bruun A, & Lubman DI (2014). Patterns of family conflict and their impact on substance use and psychosocial outcomes in a sample of young people in treatment. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies, 9(2), 114–122. doi: 10.1080/17450128.2013.855858 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen SE (2011). Two serious and challenging medical complications associated with volatile substance misuse: Sudden sniffing death and fetal solvent syndrome. Substance Use and Misuse, 46, 68–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coatsworth J, Pantin H, & Szapocznik J (2002). Familias Unidas: A family-centered ecodevelopmental intervention to reduce risk for problem behavior among Hispanic adolescents. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 5(2), 113–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon FR, Turner CW, Robbins MS, & Szapocznik J (2005). Concordance among biological, interview, and self-report measures of drug use among African American and Hispanic adolescents referred for drug abuse treatment. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 19(4), 404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans WD, Holtz K, White T, & Snider J (2014). Effects of the above the influence brand on adolescent drug use prevention normative beliefs. Journal of Health Communication, 19(6), 721–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedenthal S, Vaughn MG, Jenson JM, & Howard MO (2007). Inhalant use and suicidality among incarcerated youth. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 90(1), 81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.02.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosin M, Marsiglia FF, & Hecht ML (2003). keepin’ it R.E.A.L: A drug resistance curriculum tailored to the strengths and needs of preadolescents of the southwest. Journal of Drug Education, 33, 119–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht ML, Marsiglia FF, Elek E, Wagstaff DA, Kulis S, Dustman P, & Miller-Day M (2003). Culturally grounded substance use prevention: an evaluation of the keepin’it REAL curriculum. Prevention Science, 4, 233–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard MO, Bowen SE, Garland EL, Perron BE, & Vaughn MG (2011). Inhalant use and inhalant use disorders in the United States. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice, 6, 18–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard MO, Perron BE, Vaughn MG, Bender KA, & Garland EL (2010). Inhalant use, inhalant use disorders and antisocial behavior: Findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey of Alcohol and Related Disorders (NESARC). Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 71, 201–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. (2016). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 24.0. Armonk, MY: IBM Corp. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD (1989). The survey technique in drug abuse assessment. Bulletin of Narcotics, 41(1–2), 29–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, & Miech RA (2014). Demographic subgroup trends among adolescents in the use of various licit and illicit drugs, 1975–2013 (Monitoring the Future Occasional Paper 81). Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Miech RA, Bachman JG, & Schulenberg JE (2015). Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use: 1975–2014: Overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Stanton B, & Feigelman S (2000). Impact of perceived parental monitoring on adolescent risk behavior over 4 years. Journal of Adolescent Health, 27, 49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Ayers SL, Baldwin-White A, & Booth J (2016). Changing latino adolescents’ substance use norms and behaviors: The effects of synchronized youth and parent drug use prevention interventions. Prevention Science, 17(1), 1–12. doi: 10.1007/s11121-015-0574-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, & Hecht ML (2005). Keepin’ it REAL: An evidence-based program. Santa Cruz, CA: ETR Associates. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Kulis S, Wagstaff DA, Elek E, & Dran D (2005). Acculturation status and substance use prevention with Mexican and Mexican-American youth. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 5(1–2), 85–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Kulis S, Yabiku ST, Nieri TA, & Coleman E (2011). When to intervene: Elementary school, middle school or both? Effects of keepin’it REAL on substance use trajectories of Mexican heritage youth. Prevention Science, 12(1), 48–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGarvey EL, Canterbury RJ, & Waite D (1996). Delinquency and family problems in incarcerated adolescents with and without a history of inhalant use. Addictive Behaviors, 21, 537–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (2015). Mplus User’s Guide: Statistical Analysis with Latent Variables: User’s Guide. Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Nakawaki B, & Crano W (2015). Patterns of substance use, delinquency, and risk factors among adolescent inhalant users. Substance Use & Misuse, 50(1), 114–114. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2014.961611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen J, O’Brien C, & Schapp S (2016). Adolescent inhalant use prevention, assessment, and treatment: A literature synthesis. International Journal of Drug Policy, 31, 15–24. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2016.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonnemaker JM, Crankshaw EC, Shive DR, Hussin AH, & Farrelly MC (2011). Inhalant use initiation among U.S. adolescents: Evidence from the national survey of parents and youth discrete-time survival analysis. Addictive Behaviors, 36, 878–881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ober AJ, Miles JN, Ewing B, Tucker JS, & D’Amico EJ (2013). Risk for inhalant initiation among middle school students: Understanding individual, family, and peer risk and protective factors. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 74, 835–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsai MB, Castro FG, Marsiglia FF, Harthun ML, & Valdez H (2011). Using community based participatory research to create a culturally grounded intervention for parents and youth to prevent risky behaviors. Prevention Science, 12(1), 34–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perron B, Howard M, Maitra S, & Vaughn M (2009). Prevalence, timing and predictors of transitions from inhalant use disorders. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 100, 277–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokhrel P, Unger JB, Wagner KD, Ritt-Olson A, & Sussman S (2008) Effects of parental monitoring, parent-child communication, and parents’ expectation of the child’s acculturation on the substance use behaviors of urban, Hispanic adolescents. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, 7, 200–213. doi: 10.1080/15332640802055665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prado G, Huang S, Schwartz SJ, Maldonado-Molina MM, Bandiera FC, de la Rosa M, & Pantin H (2009). What accounts for differences in substance use among U.S.-born and immigrant Hispanic adolescents? Results from a longitudinal prospective cohort study. Journal of Adolescent Health, 45(2), 118–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.12.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schinke S, Brounstein P, & Gardner S (2002). Science-based prevention programs and principles. Rockville, MD: Center for Substance Abuse Prevention, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; DHHS Pub No. (SMA) 03–3764 [Google Scholar]

- Scott KD, & Scott AA (2013). Adolescent inhalant use and executive cognitive functioning. Child: Care, health and development, 40(1), 20–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel JT, Alvaro EM, Patel N, & Crano WD (2009). “… you would probably want to do it. Cause that’s what made them popular”: Exploring Perceptions of Inhalant Utility Among Young Adolescent Nonusers and Occasional Users. Substance Use & Misuse, 44(5), 597–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik J, & Coatsworth JD (1999). An ecodevelopmental framework for organizing the influences on drug abuse: A developmental model of risk and protection In Meyer D, & Hartel CR (Eds.), Drug abuse: Origins and interventions (pp. 331–366). Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2015). Annual Estimates of the Resident Population by Sex, Age, Race, and Hispanic Origin for the United States and States: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015 (Tech. Rep. No. NP-D1-A). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Commerce. [Google Scholar]

- Walker JMT (2016). Realizing the American Dream: A parent education program designed to engage families’ involvement. Journal of Latinos and Education. doi: 10.1080/15348431.2015.1134536 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub E, Gandhi D, Robinson C (2000). Medical complications due to mothball abuse. Southern Medical Journal, 93, 427–429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams LR, Ayers S, Baldwin A, & Marsiglia FF (2016). Delaying youth substance-use initiation: A cluster randomized controlled trial of complementary youth and parenting interventions. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research, 7(1), 177–200. [Google Scholar]