Abstract

To increase vaccine immunogenicity, modern vaccines incorporate adjuvants, which serve to enhance immune cross-protection, improve humoral and cell-mediated immunity, and promote antigen dose sparing. Pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), including the Toll-like receptor (TLR) family are promising targets for development of agonist formulations for use as vaccine adjuvants. Combinations of co-delivered TLR4 and TLR7/8 ligands have been demonstrated to have synergistic effects on innate and adaptive immune response. Here, we create liposomes which stably co-encapsulate, CRX-601, a TLR4 agonist, and UM-3004, a lipidated TLR7/8 agonist, within the liposomal bilayer in order to achieve co-delivery, allow tunable physical properties, and induce in vitro and in vivo immune synergy. Co-encapsulation demonstrates a synergistic increase in IL-12p70 cytokine output in vitro from treated human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (hPBMCs). Further, co-encapsulated formulations give significant improvement of early IgG2a antibody titers in BALB/c mice following primary vaccination when compared to single agonist or dual agonists delivered in separate liposomes. This work demonstrates that co-incorporation of TLR4 and lipidated TLR7/8 agonists within the liposomal bilayer leads to innate and adaptive immune synergy which biases a Th1 immune response. Thus, liposomal co-encapsulation may be a useful and flexible tool for vaccine adjuvant formulation containing multiple TLR agonists.

Keywords: Vaccine adjuvant, Liposome, Toll-like receptor (TLR), Co-delivery, Influenza virus, Influenza vaccine

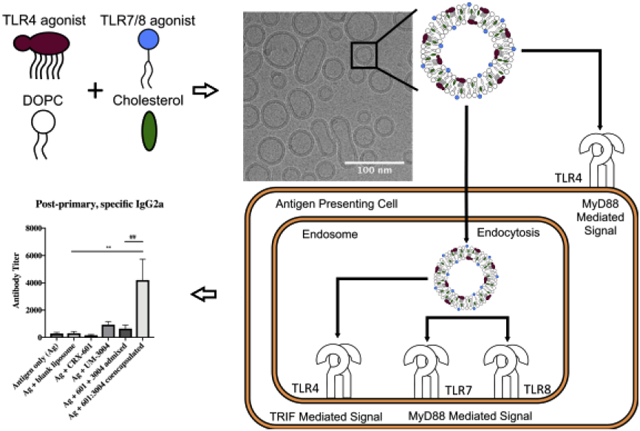

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Current recombinant and subunit vaccine technology has the promise to reduce or prevent morbidity from pernicious and prevalent diseases by pairing recombinant or subunit antigens with immune stimulating adjuvants. Modern cell culture, recombinant protein, and purification techniques have been essential to expand the repertoire of antigens available for use in vaccines. While a surfeit of antigens are available for viral, bacterial, fungal, and parasitic diseases, many lack the immunogenicity necessary to elicit an efficacious immune response [1]–[3]. Adjuvants can be added to vaccines to enhance immune cross-protection, improve humoral and cell-mediated immunity, and allow antigen dose sparing [4], [5]. Despite many years of research and development, few adjuvants are currently approved for human use. Alum [6], the oil-in-water emulsions MF59 [7] and AS03 [8], monophosphoryl lipid A (MPL) [9], AS01 [10], AS04 [11], CpG [12], and virosomes [13] have been approved in Europe and/or the USA and are considered safe and effective. Recently, there have been a number of important breakthroughs in the use of Toll-like receptor (TLR) based adjuvants including the approval of vaccines containing MPL (a TLR4 ligand) and CpG (a TLR9 ligand) [9]–[12]. These approvals help pave the way for new approaches using TLR ligands, formulations, and combinations thereof to drive improved humoral and cell mediated immunity to recombinant and subunit vaccines.

Pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) are innate immune system receptors with subfamilies capable of sensing a wide variety of exogenous pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) from pathogen components or endogenous danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). As such, PRRs are frequent and promising targets for the development of vaccine adjuvants. In particular, the TLR family of receptors sense extracellular and intracellular ligands, including bacterial and fungal cell wall lipids, viral proteins, and nucleic acid fragments [14], [15]. TLR ligands have successfully been targeted for the development of vaccine adjuvants by modification to retain immunostimulatory properties while limiting reactogenicity [16]. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is a canonical TLR4 ligand and a potent and toxic bacterial cell wall lipid which has been derivatized to MPL and has been the inspiration for synthetic mimetics like aminoalkyl glucosaminide 4-phosphates (AGPs). These modified agonists have been clinically approved [17] or continue to be tested for clinical use [18], [19], respectively, because they retain potency and efficacy while mitigating toxicity and reactogenicity [20]–[23]. TLR7/8 receptors sense ssRNA of actively replicating or degraded viruses within the endosome and offer another potential adjuvant target. Small molecule RNA mimetics such as imidazoquinolines (IQs) and oxoadenines (OAs) have been shown to specifically bind TLR7 and TLR8 and induce potent adjuvant activity [24]–[26]. The most commonly used TLR7/8 agonists resiquimod and imiquimod (IMQ) exhibit unacceptable systemic toxicity, but lipidated TLR7/8 agonists like 3M-052 and 1V270 have demonstrated reduced toxicity profiles more acceptable for human use as a vaccine adjuvant [27], [28].

TLR4 and TLR7/8 co-stimulation has been reported to result in synergistic immune responses that drive increased cytokine production and Th1-Th2 balanced responses both in vitro and in vivo [29]–[33]. By activating TLR4 and TLR7/8 receptors using simultaneous addition of LPS and the IQ compound resiquimod, Napolitani et al. report a 20–50-fold increase in IL-12p70 release from hPBMCs when compared to addition of either individual compound, which results in skewing dendritic cells (DCs) to Th1 biased responses [29]. Fox et al. also demonstrate a striking increase in IL-12p70 when stimulating hPBMCs with TLR4 and TLR7/8 agonists combined in a single liposome [30]. The increase in IL-12p70 and other IL-12 family cytokines has been previously shown to enhance Th1 responses [31], [32]. Further, dual TLR4, TLR7/8 agonist administration was demonstrated to give rapid and sustained cellular and humoral immunity and broad protection when administered as a vaccine prior to influenza challenge in mice [33]. Thus, TLR4 and TLR7/8 synergy can be leveraged as a strategy for use as an adjuvant in a subunit vaccine, resulting in enhanced antigen-specific immunity.

Co-delivery of TLR4 and TLR7/8 agonists in proper spatial and temporal frames to cells co-expressing both TLRs, and thus as a formulation and delivery strategy, is key to unlocking immune synergy [29], [34]. In early experiments demonstrating TLR synergy, TLR4 and TLR7/8 synergy has been reported to be dependent on co-expression of receptors on the same cell, which enhances memory B cell and plasma cell responses [35]. TLR4 and TLR7/8 are spatially separated since TLR4 resides in the cell membrane and TLR7/8 within the endosome, though TLR4 can be endocytosed upon ligand binding. These TLRs can also signal through different adapter molecules, as early TLR4 signaling from the cell membrane depends on MyD88 and late TLR4 signaling depends on TIR domain-containing adaptor protein inducing interferon beta (TRIF) [36], [37], but TLR7/8 signaling is dependent upon MyD88 [23], [24]. As such, immune synergy has been demonstrated to be not only TLR4 and TLR7/8 dependent, but also MyD88 and TRIF dependent. [40], [41]. Additionally, reported TLR4 and TLR7/8 synergy has a temporal but not ordinal component since maximal synergy has been described when TLR agonists are delivered within a window of 4 hours, though order of delivery within this window seems inconsequential [29]. Thus, co-delivery of TLR4 and TLR7/8 agonists spatially by cellular location and within a proper temporal window may ensure both MyD88 and TRIF activation and result in synergy [39], which likely mimics simultaneous detection of any cell wall components and nucleic acids of a pathogen and drives a more robust immune response.

While simple mixing of TLR7/8 and TLR4 agonists can be an effective way to induce immune synergy, co-encapsulation of the agonists within the same liposome could offer more effective delivery for co-activation in the same cell. Previous studies report the delivery of TLR agonists as an admixture of compounds dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), incorporated within separate biodegradable poly(lactic co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) particles, or combined in a co-liposome [30], [33], [35], [40], [42]–[44]. Admixed DMSO formulations have effectively caused synergy and Th1 biasing in mouse models, but DMSO admixtures do not ensure TLR4 and TLR7/8 co-agonism due to inefficient delivery [33], [40]. PLGA offers efficient encapsulation and particle stability, but release kinetics are typically slow and incomplete [42]. Alternatively, co-liposomes may provide a clinically relevant alternative, but results show that IMQ, an IQ, shows very low encapsulation efficiency within the internal aqueous compartment of the liposome when combined with glucopyranosyl lipid adjuvant (GLA), a TLR4 agonist incorporated within the bilayer of the liposome [30]. To mitigate these limitations, lipidation of IQs has been a technique used to allow stable incorporation into liposomal bilayers [27], [45], and TLR4 agonists are frequently formulated in the liposomal bilayer, including AS01, a liposome containing MPL recently approved for use in a Herpes zoster vaccine [46]. One group has previously combined GLA and 3M-052, a lipidated TLR7/8 agonist, within the bilayer of a liposome, which improved agonist encapsulation and drove synergistic cytokine response, Th1-type immune biasing, and partial protection as a subunit vaccine against Entamoeba histolytica [43], [44].

We hypothesize that co-encapsulating CRX-601, a synthetic TLR4 agonist [47], and UM-3004, a novel, lipidated IQ and TLR7/8 agonist, within the bilayer of a liposome will result in stable particles of sterile filterable size that will improve agonist recovery. In addition, we hypothesize these co-encapsulated liposomes will drive a synergistic immune response. To produce optimal co-encapsulated liposomes, total amount of excipients was adjusted to maximize incorporation of CRX-601 and UM-3004, and the TLR ratio was tuned to maximize innate and adaptive immune responses. The resulting CRX-601 and UM-3004 co-encapsulated liposomes were characterized by physical properties, including size, polydispersity, and surface charge, and recovery of agonist after filtration. Immune synergy of co-encapsulated CRX-601 and UM-3004 was tested by measuring in vitro innate cytokine release from hPBMCs, and BALB/c mice were used to demonstrate in vivo antigen-specific adaptive immune response to the monovalent detergent-split influenza vaccine A/Victoria/210/2009-H3N2 (A/Vic). In order to determine if the strategy of co-encapsulation provided a formulation advantage compared to admixtures, the co-encapsulated liposomes were compared to admixtures of single agonist liposomes in both the in vitro and in vivo studies.

2. Methods

2.1. Liposome preparation

A liposome system containing DOPC and cholesterol was chosen as both components are biocompatible. Each is an endogenous cell membrane component and has low immunogenicity, and similar liposomes have been approved for human use as part of the AS01 adjuvant system [10], [48]. Additionally, this lipid system has been demonstrated to efficiently incorporate various lipidated TLR4 agonists, including MPL [49], and 1V270, a lipidated TLR7/8 agonist [20], [33]. DOPC was purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids, cholesterol was purchased from Sigma, and CRX-601 and UM-3004 were synthesized as described previously [21], [50]. An initial screen was done in order to determine the total amount of DOPC and cholesterol necessary to best incorporate CRX-601 and UM-3004. DOPC:cholesterol was maintained at a mass ratio of 4:1, namely, DOPC:cholesterol of 7.50:1.88, 15.0:3.75, 40.0:10.0, or 60.0:15.0 mg/mL. An initial molar ratio of UM-3004:CRX-601 10:1 was chosen based on TLR7/8:TLR4 ratios that have previously demonstrated immune synergy [29]. The final concentrations of UM-3004 and CRX-601 were targeted to 1.70 μM (2.0 mg/mL) and 0.17 μM (0.26 mg/mL), respectively. When ratios of UM-3004 to CRX-601 were adjusted, UM-3004 remained at a target concentration of 2 mg/mL, and CRX-601 was adjusted to molar ratios of 1:1, 10:1, or 100:1 in a DOPC:cholesterol liposome with a mass ratio of 40:10 mg/mL.

Liposomes were prepared using thin-film rehydration [51]. Briefly, lipids were individually dissolved in chloroform to make stocks, and lipid stocks were added to a round bottom flask and mixed. Solvent was evaporated using a Rotavap set to 150 rpm in a water bath at 45–50°C, and residual solvent was removed by storing overnight under reduced pressure at room temperature. Thin films were rehydrated with 50 mM sodium phosphate and 100 mM NaCl at pH 6.0. Formulations were sonicated in an Elma 9331 bath sonicator at temperatures between 45–55°C (above the transition temperature of all compounds) until particle size was reduced below 0.22 μm or the samples appeared opalescent and particle size did not change upon further sonication. Samples were sterile filtered using a 13 mm Millex GV PVDF filter with a pore size of 0.22 μm. Since presence of endotoxin would cause unwanted TLR4 agonism, all liposomes were made in a BioChemGard biosafety cabinet using aseptic technique, endotoxin-free consumables, and depyrogenated glassware. Glassware was depyrogenated by heating to 250 °C for 60 minutes in a BlueM Lab Oven, and other materials were chemically depyrogenated by soaking in a solution of 0.4% sodium hydroxide in 95% v/v ethanol for 30 minutes, followed by rinsing with sterile water for irrigation (WFI).

2.2. Characterization of Liposomes

Liposomes were physically characterized by measuring particle size, polydispersity, zeta-potential, pH, and osmolality. Particle size and polydispersity were measured by DLS using a Malvern Zetasizer Nano-ZS. Samples were diluted 1:10 in WFI, and three measurements were averaged to determine particle size and polydispersity. Particle size is given in diameter based on the Intensity (Z.avg) or Number functions for DLS and compared to measurements taken from cryo-EM images. Zeta-potential was measured in folded capillary cells on the Malvern Zetasizer by diluting samples 1:20 in WFI. Sample dilutions were measured at 25 °C, and conductivity of the diluted samples was determined to be 1.43±0.44 mS/cm, which is similar to 10 mM NaCl, so the Smoluchowski approximation was used to determine zeta-potential. An Accumet AB150 pH meter (Fisher Scientific) and a Mettler-Toledo InLab Micro probe were after a three-point calibration using pH 4.01, 7.00, and 10.01 standards. Osmolality was measured using a Wescor VAPRO 5520 Vapor Pressure Osmometer after calibration with 290, 100, and 1000 mmol/kg standards. For colloidal stability, formulations were measured by DLS for particle size after 9 months storage at 4 °C.

Concentrations of CRX-601 and UM-3004 were determined by RP-HPLC using a Waters 2695 separations module and a 2489 UV/Vis detector. Liposomes were dissolved in 9:1 v/v THF:methanol and eluted on a ACE 3 C8 50 × 3.0 mm id column and Phenomenex C8 guard column. A stock of 250 mM TBAOH was made in HPLC water and pH adjusted to 6.0 with concentrated phosphoric acid to buffer organic and aqueous mobile phases. Mobile phase A consisted of 2% v/v TBAOH stock and 8% v/v ACN in HPLC water, while the Mobile phase B consisted of 2% v/v TBAOH in ACN. The following reverse phase gradient, given in T(min), was run for each sample injection at 0.8 mL/min: T0 %A 95 %B 5, T10 %B 100, T15 %B 100, T17.1 %A 95 %B 5, T20 %A 95 %B 5. CRX-601 absorbance was measured at 210 nm, and UM-3004 absorbance was measured at 254 nm. Both compounds were quantitated by peak area based on interpolation from a seven-point dilution series of the corresponding standard. Recovery of CRX-601 and UM-3004 was determined by comparing pre- and post-sterile filtration sample concentrations.

Electron microscopy was performed at the Multiscale Microscopy Core (MMC) with technical support from the Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU)-FEI Living Lab and the OHSU Center for Spatial Systems Biomedicine (OCSSB). Samples were imaged using a FEI Talos Arctica system with a FEI Ceta 16M CMOS camera. Samples were prepared by transferring them to Quantifoil EM grids and freezing them in liquid ethane using a Vitrobot prior to imaging. When necessary, samples were diluted with sample buffer. Images were processed and particles sizes measured using the Fiji distribution of ImageJ from NIH [52].

2.3. In vitro innate cytokine output

Commercially available ELISA kits were used to measure TNFα and IL-1β (R&D Systems) and IL-12p70 and IFNα (PBL Assay Science) from the supernatant of hPBMC cell cultures. Blood was drawn from healthy human donors with informed consent and University of Montana IRB approval in accordance with HHS guidelines. PBMCs were separated from whole blood using a Ficoll-Hypaque 1.077 gradient, cultured in RPMI media supplemented with 10% FBS and penicillin/streptomycin/glutamine (complete media), and treated with liposome formulations. Liposomes consisted of DOPC:cholesterol with incorporated CRX-601, UM-3004, UM-3004:CRX-601 co-encapsulated, or CRX-601 and UM-3004 liposomes admixed. Liposomes were dosed in a 1 to 5 dilution series. Supernatants were harvested 18–24 hours after treatment and ELISAs were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cytokine concentration was determined by OD 450 nm values interpolated from a 7-point standard curve of a reference standard.

2.4. In vivo serum antibody titer determination after vaccination

Female 6–8 week old BALB/c mice from Envigo were used for in vivo studies. Mice were housed in an AAALAC accredited facility and all procedures were performed in accordance to the UM IACUC approved animal use protocol. Mice were immunized twice, 14 days apart, by intramuscular injection in the hind limb with 0.15 μg of detergent-split influenza vaccine A/Victoria/210/2009-H3N2 (A/Vic, provided by GlaxoSmithKline) and various liposomal formulations. Formulations consisted of DOPC:cholesterol (40:10 mg/mL) liposomes with incorporated CRX-601, UM-3004, UM-3004:CRX-601 co-encapsulated, or CRX-601 and UM-3004 liposomes admixed. All formulations containing UM-3004 were dosed at 1.0 μg (0.85 nmol) UM-3004 per mouse and those containing CRX-601 were dosed at 0.15 μg (0.1 nmol) CRX-601 per mouse. To account for dosing of DOPC and cholesterol, the DOPC:cholesterol only vehicle was matched to the largest sample volume used, which represents the largest amount of DOPC and cholesterol.

At 14 days post-primary injection, blood was collected by submandibular bleed from 8 mice per group, serum was separated using Microtainer Serum Separator Tubes (BD Biosciences), and the secondary immunization was given by intramuscular injection in the contralateral hind limb. 14 days after the secondary immunization, 7 mice per group were anesthetized and terminally bled. Serum was analyzed via ELISA for influenza-specific total IgG, IgG1 and IgG2a antibody concentration. Serum was diluted according to the expected antibody response (between 1:10 and 1:5000). Assay plates were prepared by coating MaxiSorp ELISA plates (Nunc) with 100 μl of A/Vic antigen at 1 μg/mL, washing in 1x PBS + 0.05% Tween-20, and blocking with SuperBlock (Scytek Laboratories). Plates were then incubated with diluted serum for 1 hour followed by binding with anti-mouse IgG-, IgG1- or IgG2a-HRP secondary antibody (Bethyl Laboratories) and detection using TMB Substrate (BD Biosciences). Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a Molecular Devices SpectraMax 190 microplate reader, and antibody titers were determined by calculating titer of each sample at OD 0.3.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistics were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 8 software. Results were confirmed for normality using the D’Agostino-Pearson omnibus normality test, and one-way ANOVA was used to determine variances in means between formulation groups. Dunnett’s test was used for post-hoc comparison of means (p < 0.05 *, < 0.01 **, and < 0.001 ***).

3. Results and Discussion

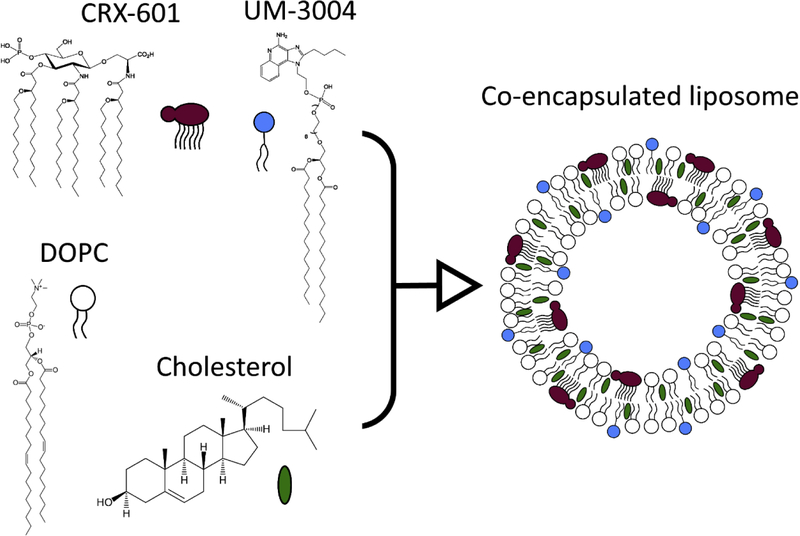

In this study, UM-3004, a lipidated IQ and TLR7/8 agonist, and CRX-601, a synthetic TLR4 agonist, were co-encapsulated within the bilayer of liposomes based on a DOPC and cholesterol lipid system (Figure 1). The co-encapsulation of the two TLR agonists and physical properties of the resulting liposomes were characterized qualitatively and quantitatively, and the liposomes were tested for their ability to elicit an innate and adaptive immune response.

Figure 1: Structures of compounds used and liposomal co-encapsulation.

Co-encapsulated liposomes were made with CRX-601, a TLR4 agonist, and UM-3004, a TLR7/8 agonist. A system of DOPC and cholesterol was used as the base of the liposomes. Lipid moieties present in CRX-601 and UM-3004 allowed incorporation in the liposomal bilayer.

3.1. Qualitative characterization of liposomes

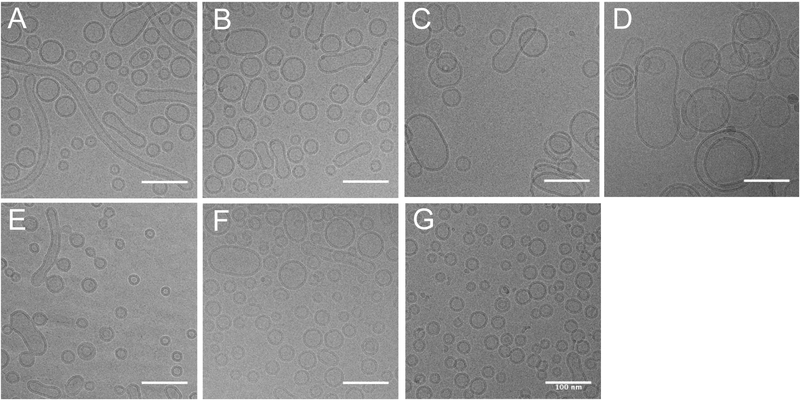

First, we determined how total amount of lipid excipient impacts the formation of liposomes and TLR incorporation, so the total amount of DOPC and cholesterol were varied while maintaining a constant weight ratio of 4:1. Formulations containing both UM-3004 and CRX-601 agonists with different total lipid amounts were compared to single agonist and DOPC:cholesterol only controls. In order to determine particle shape, size, and liposome lamellarity, formulations were analyzed by cryo-EM and compared to controls (Figure 2).

Figure 2: DOPC:cholesterol weight ratio of 40:10 mg/mL produces the most uniform liposomes with incorporated TLR4 and TLR7/8 agonists.

UM-3004 and CRX-601 were co-encapsulated in DOPC:cholesterol liposomes and observed using cryo-EM microscopy at 17,500x magnification. UM-3004 and CRX-601 were maintained at a molar ratio of 10:1, with the target concentration of UM-3004 at 1.70 μM (2.0 mg/mL). The amount of DOPC:cholesterol was varied while maintaining a 4:1 mass ratio of DOPC:cholesterol, with respective concentrations of (A) 60:15 mg/mL, (B) 40:10 mg/mL, (C) 15:3.75 mg/mL, and (D) 7.5:3.88 mg/mL. These results were compared to (E) CRX-601 0.17 μM (0.26 mg/mL), (F), UM-3004 1.70 μM (2.0 mg/mL), or (G) DOPC:cholesterol only controls, with total DOPC:cholesterol held at 40:10 mg/mL for (E-G). Scale bars represent 100 nm.

Qualitative results demonstrate that all agonist and control formulations form liposomes with a distinct bilayer, the majority of which are unilamellar (Fig. 2A–G). When CRX-601 or UM-3004 alone are formulated in phosphate buffer in the absence of excipients, each forms insoluble aggregates visible without microscopy (results not shown). Thus, the preponderance of particles with distinct bilayer formation and the lack of particulate matter here show that CRX-601 and UM-3004 are incorporated in liposomes singly in controls or co-encapsulated within liposomes in dual agonist formulations. Size and shape of liposomes in dual agonist formulations demonstrate a dependence on total lipid amount (Fig. 2A–D). In formulations containing more total lipid, particles smaller than 100 nm in diameter predominated (Fig. 2A–B), but in formulations containing less total lipid, particles larger than 100 nm predominated (Fig. 2C–D). Unexpectedly, the formulation containing the most total lipid (60:15 mg/mL DOPC:cholesterol) showed the presence of long tubular vesicles. Similar tubular vesicles were observed to a minor extent in single agonist formulations containing CRX-601 or UM-3004 (Fig. 2E, F). Since all samples were sterile filtered using a 0.22 μm pore size filter before microscopy, the formation of tubular vesicles may be a result of aggregation of sample in the time between filtration and microscopy (approximately 2 weeks). Though samples prepared with 60:15 or 40:10 mg/mL DOPC:cholesterol both form similarly sized liposomes (<100 nm) Fig. 2A–B, more total lipid (60:15 mg/mL) pushed toward formation of the tubular vesicles.

3.2. Physical characterization of liposomes

In order to quantify physical properties of all formulations, the liposomes were analyzed by measuring size, polydispersity (PDI), zeta-potential, and osmolality (Table 1).

Table 1: Increasing total lipid content results in reduced particle size and polydispersity of co-encapsulated liposomes.

DOPC:cholesterol was used as a liposome system to co-encapsulate UM-3004 and CRX-601. DOPC:cholesterol mass ratio was maintained at 4:1, and the total amount of DOPC:cholesterol was adjusted. UM-3004 and CRX-601 were maintained at a molar ratio of 10:1, with UM-3004 at a target concentration of 1.70 μM (2.0 mg/mL) and CRX-601 at a target concentration of 0.17 μM (0.26 mg/mL). UM-3004 and CRX-601 only controls were formulated at 1.70 μM and 0.17 μM, respectively. Physical properties are given as the mean ± SEM (n=4).

| Formulation | Total Lipid Amount | Size (Z-avg, d.nm) | PDI | Zeta-potential (mV) | pH | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DOPC (mg/mL) | Cholesterol (mg/mL) | |||||

| UM-3004: CRX-601 | 7.50 | 1.88 | 198 ±12 | 0.480 ±0.093 | −37.0 ±0.2 | 6.04 ±0.01 |

| 15.0 | 3.75 | 163 ±17 | 0.407 ±0.042 | −17.2 ±2.9 | 6.05 ±0.01 | |

| 40.0 | 10.0 | 118 ±21 | 0.303 ±0.035 | −6.4 ±0.1 | 6.05 ±0.01 | |

| 60.0 | 15.0 | 74 ±7 | 0.242 ±0.008 | −4.6 ±0.3 | 6.04 ±0.01 | |

| UM-3004 only | 40.0 | 10.0 | 594 ±253 | 0.741 ±0.141 | −2.6 ±0.2 | 6.07 ±0.02 |

| CRX-601 only | 40.0 | 10.0 | 276 ±168 | 0.570 ±0.172 | −2.7 ±0.7 | 6.07 ±0.00 |

| DOPC:cholesterol | 40.0 | 10.0 | 51 ±3 | 0.250 ±0.014 | −0.8 ±0.3 | 5.90 ±0.02 |

The hydrodynamic diameter of particles and PDI, as measured by DLS, confirm an inverse relationship between total lipid amount and size and PDI for co-encapsulated liposomes (Table 1). Specifically, the more total lipid present, the smaller particle size or PDI. Increased amount of total lipid results in decreased particle size with 60:15 mg/mL DOPC:cholesterol giving minimum observed particle size 74 ±7 nm, and 7.5:1.88 mg/mL DOPC:cholesterol giving size 198 ±12 nm. The minimum observed PDI was 0.242 ±0.008, and the maximum observed was 0.480 ±0.093. These results show that by increasing the amount of total lipid, UM-3004:CRX-601 co-encapsulated liposomes become smaller and more uniform. The result for 60:15 mg/mL DOPC:cholesterol likely differs from qualitative results (Figure 2) due to vesicular fusion during the time between production of the liposomes and microscopy (~2 weeks). Our lead co-encapsulated formulation of UM-3004:CRX-601 in 40:10 mg/mL DOPC:cholesterol was measured for particle size stability when stored at 4 °C. Replicates of this formulation exhibited an 11% increase in particle size after storage for 9 months at 4 °C which we consider to be sufficient colloidal stability for preclinical work (data not shown).

The inverse relationship between total lipid amount and particle size was also supported by measuring particles in cryo-EM images (Supplement 1). 60:15 mg/mL DOPC:cholesterol gave the minimum observed particle size of 40.7 ±0.7 nm (n =512), and 7.5:1.88 mg/mL DOPC:cholesterol gave the maximum observed particle size of 71.8 ±4.4 nm (n =191). The larger sizes in DLS compared to cryo-EM measurements is due to the ‘Intensity’ measurement for DLS and sample PDI, which together bias larger particles [53], where direct measurement in microscopy biases smaller, more abundant particles and is more similar to the ‘Number’ measurement [54]. Since all formulations were size reduced after rehydration using bath sonication, a higher energy technique like extrusion or microfluidization could lead to even smaller, more uniform, and more stable formulations.

Zeta-potential measurements demonstrate an inverse relationship between the total lipid amount and net surface charge in UM-3004:CRX-601 co-encapsulated liposomes. The minimum observed net surface charge was −4.6 ±0.3 mV in 60:15 mg/mL DOPC:cholesterol formulations, and the maximum observed zeta-potential was −37.0 ±0.2 mV. These results imply that by increasing the amount of total lipid, the anionic charge is effectively diluted by adding more zwitterionic DOPC. This observation also gives indirect evidence that the amount of agonist per particle is reduced by increasing the total lipid amount. Since CRX-601 has a formal charge of −2 and UM-3004 has a formal charge of −1 at pH 6.0 (Figure 1), the anionic charge may be explained by preferential incorporation of CRX-601 relative to UM-3004 rather than differences in charge, which we have observed in prior studies (results not shown).

Osmolality results for co-encapsulated liposome formulations show no significant difference of effect when differing total lipid amounts. This suggests that osmolality is dependent on the buffer composition and not the total lipid amount at these concentration ranges of lipid. Additionally, osmolality for all formulations is isotonic upon dilution with antigen and thus within acceptable range for parenteral administration.

3.3. Recovery of TLR agonists after filtration

In order to determine if increasing the total lipid amount affects agonist recovery, RP-HPLC was used to determine CRX-601 and UM-3004 concentrations in pre- and post-filtered liposomes (Table 2).

Table 2: DOPC:Cholesterol weight ratio of 40:10 mg/mL gives highest TLR4 and TLR7/8 agonist recovery.

UM-3004 and CRX-601 were co-encapsulated in liposomes with varying amounts of DOPC:cholesterol. Co-encapsulated or single agonist liposomes were prepared with a target concentration of 1.70 μM (2.0 mg/mL) UM-3004 and/or a target concentration of 0.17 μM (0.26 mg/mL) CRX-601. For co-encapsulated liposomes, the target molar ratio of UM-3004:CRX-601 was held at 10:1. RP-HPLC was used to determine actual concentrations of UM-3004 and CRX-601 before and after sterile filtration through a 0.22 μm filter. Compound concentrations are given as mean ± SEM (n= 3–4).

| Sample | Total Lipid Amount | 3004 pre-filt. (μM) | 3004 post-filt.(μM) | 3004 Recovery (%) | 601 pre-filt.(μM) | 601 post-filt.(μM) | 601 Recovery (%) | Molar Ratio (3004/601) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DOPC (mg/mL) | Cholesterol (mg/mL) | ||||||||

| UM-3004: CRX-601 | 7.50 | 1.88 | 1.39 ±0.05 | 0.35 ±0.16 | 25.0 ±4.1 | 0.15 ±0.02 | 0.11 ±0.01 | 71.4 ±7.1 | 3.3 ±0.6 |

| 15.0 | 3.75 | 1.64 ±0.06 | 0.80 ±0.16 | 49.0 ±12.6 | 0.14 ±0.03 | 0.11 ±0.01 | 84.0 ±2.5 | 6.9 ±1.5 | |

| 40.0 | 10.0 | 1.47 ±0.09 | 1.14 ±0.16 | 77.7 ±4.9 | 0.13 ±0.05 | 0.11 ±0.003 | 85.4 ±3.3 | 10.2 ±0.3 | |

| 60.0 | 15.0 | 1.31 ±0.07 | 0.84 ±0.16 | 63.8 ±14.3 | 0.14 ±0.05 | 0.08 ±0.013 | 53.6 ±9.6 | 11.2 ±0.2 | |

| UM-3004 only | 40.0 | 10.0 | 1.60 ±0.06 | 0.84 ±0.32 | 52.8 ±21.1 | - | - | - | - |

| CRX-601 only | 40.0 | 10.0 | - | - | - | 0.16 ±0.03 | 0.18 ±0.02 | 107.4 ±4.2 | - |

RP-HPLC results demonstrate that increasing the total amount of DOPC and cholesterol favors recovery of CRX-601 and UM-3004 up to 40:10 mg/mL. This amount of total lipid results in 77.7 ±4.9% recovery of UM-3004 and 85.4 ±3.3% recovery of CRX-601. Further increasing the total amount of lipid decreases recovery of both CRX-601 and UM-3004, which may be due to the propensity of the formulation to aggregate at the highest total lipid concentrations (Fig 2A). Recovery of TLR4 and TLR7/8 agonists here is similar to recoveries of GLA and 3M-052 in the first reported liposome co-encapsulation study by Abhyankar et al. [44]. In that study, TLR agonists are incorporated in a mixed lipid system of 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DPPC), PEGylated 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (DSPE)-PEG, and cholesterol. Liposomes composed of saturated lipids have different physical properties, including higher rigidity compared unsaturated lipid systems [55]. In addition, PEGylated liposomes have different physical properties than non-PEGylated liposomes, including a larger radius of hydration leading to longer time to elimination [56]. Since these two liposome systems are physically dissimilar, similar incorporation and recovery of TLR4 and lipidated TLR7/8 agonists within the liposomal bilayer demonstrates that co-encapsulation within the liposomal bilayer is a robust formulation strategy for these types of synthetic agonists. More broadly, using a lipidated TLR7/8 agonist to co-encapsulate both agonists within the bilayer of a liposome shows marked improvement in TLR7/8 recovery when compared to previously reported TLR4, TLR7/8 co-delivery strategies. A comparison between encapsulation efficiency within the liposomal bilayer here and within the liposomal aqueous compartment in a different study shows an 11-fold increase in encapsulation efficiency of the lipidated UM-3004 (77.7%) agonist compared to a 7% pre-filtration loading efficiency of the aqueous IQ TLR7/8 agonist IMQ [30]. Another deliver strategy incorporates a TLR7/8 agonist within PLGA particles and shows greater than 96% encapsulation efficiency, but less than 10% of the agonist is released with 10 days [42]. Taken together, co-encapsulation of TLR agonists into the liposomal bilayer is a suitable approach to increase both the encapsulation efficiency and recovery of TLR agonists but is dependent on the availability of lipidated TLR7/8 agonists.

In addition maximizing recovery of the TLR ligand, a target molar ratio of 10:1 UM-3004:CRX-601 was maintained in the 40:10 mg/mL DOPC:cholesterol formulation (Table 2). Though this target ratio of TLRs was maintained in this formulation, recovery results indicate that CRX-601 preferentially incorporates compared to UM-3004 in the same lipid formulation. When comparing incorporation of the individual components, UM-3004 recovery (52.8 ±21.1%) after sterile filtration indicates the loss of UM-3004 as particles larger than the filter size, while all of the pre-filtration CRX-601 (107.4 ±4.2%) is recovered. UM-3004 recovery could be improved with a higher energy particle size reduction technique like extrusion or microfluidization.

Due to superior TLR agonist incorporation in liposomes as demonstrated by high recovery, optimal size and polydispersity, and stability, the 40:10 mg/mL weight ratio of DOPC:cholesterol was chosen as the vehicle for in vitro and in vivo experiments with co-encapsulated TLR4 and TLR7/8 agonists.

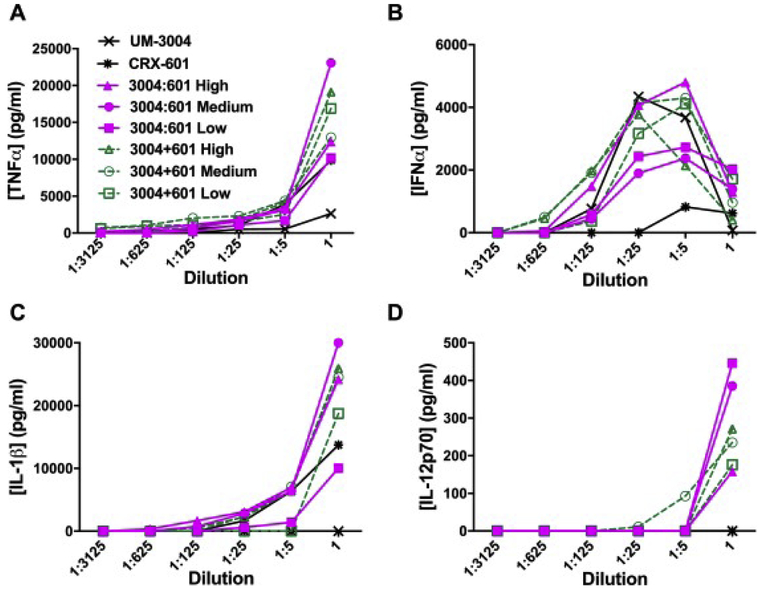

3.4. In vitro determination of innate cytokine release

To determine the innate immune response in vitro to co-encapsulated CRX-601 and UM-3004, hPBMCs were treated with serial dilutions of UM-3004:CRX-601 co-encapsulated liposomes. Liposomes were prepared to target UM-3004:CRX-601 molar ratios of 1:1 (high), 10:1 (medium), or 100:1 (low) and were compared to CRX-601 only, UM-3004 only, and CRX-601 and UM-3004 only liposomes admixed at the same target ratios. Innate cytokine release was then measured by specific ELISAs for TNFα, IFNα, IL-1β, and IL-12p70 (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Co-encapsulation of TLR4 and TLR7/8 agonists has synergistic output of IL-12p70 in hPBMCs.

hPBMCs were treated with formulations containing high (1.5:1), medium (8.5:1), or low (135:1) molar ratios of UM-3004:CRX-601 in DOPC:cholesterol liposomes. Co-encapsulated liposomes (UM-3004:CRX-601, magenta, solid lines) were compared to admixed liposomes (UM-3004+CRX-601, green, dashed lines) and to CRX-601 and UM-3004 only liposomes. Formulations were dosed in a 1:5 dilution series with the top dose of UM-3004 held constant at 120 μM (24 nmol) for all formulations containing UM-3004. CRX-601 dosing depended on molar ratio of UM-3004:CRX-601. The top dose of high molar ratio formulations was 80 μM (16 nmol), which was matched for the CRX-601 only control. hPBMCs were incubated with liposomes for 18–24 hours and supernatants were harvested and tested for (A) TNFα, (B) IFNα, (C) IL-1β, and (D) IL-12p70, with cytokine concentrations given in pg/mL.

TNFα is an early pro-inflammatory cytokine whose production is necessary for generating an immune response at the site of delivery. Here, TNFα is robustly produced when hPBMCs are treated with either co-encapsulated or admixed liposomes containing CRX-601 and UM-3004, or CRX-601 liposomes alone (Fig. 3A). Since CRX-601 only shows TNFα production and UM-3004 liposomes show only limited production of TNFα, TNFα generation is most likely due to TLR4 agonism from these formulations. Additionally, TNFα does not seem to depend on increased amounts of UM-3004 when changing agonist ratios which suggests that addition of a TLR7/8 agonist does not abrogate a TLR4 mediated immune response. Though TLR4 and TLR7/8 agonists have both been reported to produce TNFα [27], [57], TNFα production can be dependent on formulation strategy, as the lipidated TLR7/8 agonist 3M-052 prepared as an oil-in-water emulsion produces no TNFα but its core molecule resiquimod does [58]. Alternatively, TLR7 or TLR8 receptor biasing based on specific IQ structure can determine TNFα production, though biasing for UM-3004 was not determined here [59].

Previous research reports that TLR7/8 agonism contributes to the IRF mediated IFNα response which mediates innate and adaptive immunity through multiple Interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) [60]. ISGs perform a myriad of functions, one of which being the induction of an antiviral immune state [61]. Here, IFNα secretion demonstrates a dose dependent response to treatment with admixed or co-encapsulated CRX-601 and UM-3004 or to UM-3004 alone (Fig. 3B). Since IFNα is secreted in all formulations containing the TLR7/8 agonist, IFNα production is therefore determined by the dose of UM-3004 alone. Notably, addition of the TLR4 agonist does not interfere with TLR7/8 mediated induction of IFNα, and since IFNα induction peaks 20 uM, while TNFα peaks at higher doses, this suggests agonism of different receptors Additionally, the drop-off in IFNα production at the highest doses of UM-3004 may be due to TLR7/8 activation induced cell death, which has been observed in vitro at high doses of OAs [25].

Production of IL-1β in conjunction with IFNα has been determined to be crucial to host defense response by regulating immune mediated inflammation, adaptive immunity, and antiviral control [62]. All formulations containing the TLR4 agonist CRX-601 stimulate IL-1β release, but it is absent in the liposome containing UM-3004 alone (Fig. 3C). This suggests that TLR4 but not TLR7/8 agonist is capable of IL-1β production within these liposomal formulations. High (1:1) and medium (10:1) molar ratios of UM-3004 to CRX-601, whether co-encapsulated or admixed, drove the greatest IL-1β release. Since TLR4 signals through a Myd88 dependent mechanism on the cell surface and leads to production of pro-IL-1β [63], CRX-601 likely activates this pathway. Further, since type I interferons can induce caspase activity in a feed forward loop through the inflammasome resulting in cleavage of pro-IL-1β to form activated IL-1β [64], the combination of UM-3004 and CRX-601 may be contributing to increased secretion of IL-1β with the co-encapsulated or admixed formulations.

Lastly, IL-12p70 production has been reported to push a Th1 biasing immune response resulting in rapid and sustained cell mediated and humoral immunity [32], [65]. Neither liposomal CRX-601 nor UM-3004 alone elicits IL-12p70 production, but when cells were stimulated with both agonists, whether admixed or co-encapsulated in liposomes, IL-12p70 was produced (Fig. 3D), which is in accordance to findings with previous reports regarding synergistic production of IL-12p70 from co-delivery of TLR4 and TLR7/8 agonists [30], [33], [40]. Since TLR4 and TLR7/8 are required for immune synergy through both MyD88 and TRIF signaling adapters and TRIF signaling only occurs from internalized TLR4 receptors [40], [41], [66], co-encapsulated liposomes likely co-deliver agonists to not only the same cell but the same endosome. Multiple TLR interaction partners in distinct subcellular compartments have been reported to influence signaling, so co-encapsulation strategies could drive immune synergy [39].

3.5. In vivo determination of antigen specific antibody titers

In order to determine the effects of TLR4 and TLR7/8 agonist co-delivery on adaptive immunity, BALB/c mice were used as a model system in an immunization study. Mice were immunized twice, 14 days apart with A/Vic antigen adjuvanted with liposomal formulations of UM-3004 or CRX-601 alone, admixed, or co-encapsulated. A formulation of 10:1 target molar ratio of UM-3004:CRX-601 was selected due to maximal activity in in vitro studies, and separate UM-3004 and CRX-601 liposomes were admixed to this molar ratio for comparison of equivalent dosage. TLR4 and TLR7/8 were administered in suboptimal doses to explore the possible synergistic effects of liposomal co-encapsulation.

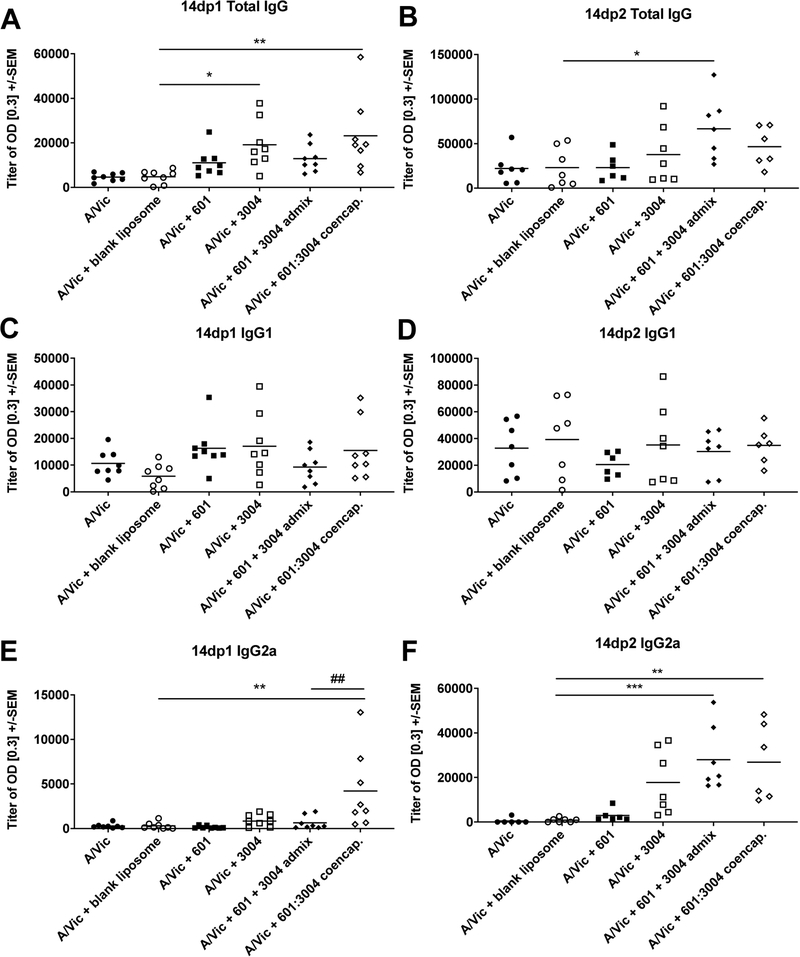

Two weeks after primary and secondary immunization, serum was collected and antigen-specific IgG, IgG1, and IgG2a antibody titers were determined by ELISA (Figure 4). It should be noted that both mice and humans express TLR7 and TLR8 receptors, but since TLR8 receptors in mice have limited functionality and are differentially expressed [67], resultant effects of co-encapsulated liposomes are likely the result of TLR4 and/or TLR7 dependent signaling.

Figure 4: Co-encapsulation of TLR4 and TLR7/8 agonists significantly increases early IgG2a antibody response.

Antibody titers, including total IgG, IgG1, and IgG2a were measured from the serum of BALB/c mice fourteen days post-primary vaccination (14dp1: A, C, E; n=8) and fourteen days post-secondary vaccination (14dp2: B, D, F; n=7) with 0.15 μg A/Victoria/210/2009-H3N2 (A/Vic) antigen and liposome formulations. Liposome formulations contained 1.0 μg (0.85 nmol) UM-3004 or 0.15 μg (0.10 nmol) CRX-601 separately, admixed, or co-encapsulated. One-way ANOVA demonstrates significant effect of adjuvant addition for post-primary total IgG (p < 0.01) and IgG2a (p < 0.01) and for post-secondary total IgG (p < 0.05) and IgG2a (p < 0.0001), with post-hoc Dunnett’s test demonstrating significant differences between means (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001) when compared to blank liposomes + A/Vic (*) or CRX-601 + UM-3004 admixed liposomes (#).

Results demonstrate that the addition of adjuvant to a blank liposome + A/Vic antigen has a significant effect on both total IgG (p < 0.01) and IgG2a (p < 0.01) but not on IgG1 antibody titers when measured 14 days post-primary vaccination (Fig. 4A, C, E). At 14 days post-primary vaccination, co-encapsulation of TLR4 and TLR7/8 agonists leads to significantly greater total IgG titers compared to antigen alone or blank liposome + antigen, though not different from CRX-601, UM-3004, or admixed CRX-601 + UM-3004 (Fig. 4A). Increase in total IgG titer is likely due to the increase in IgG2a Th1-type antibodies, since IgG1 antibodies do not significantly differ across formulations. Strikingly, 14 days post-primary immunization, the humoral response to co-encapsulated UM-3004:CRX-601 leads to a 14-fold increase in IgG2a titer when compared to the blank liposome + antigen (Fig. 4E), and co-encapsulation leads to a 6.5-fold increase when compared to TLR4 and TLR7/8 admixed liposomes (Fig. 4E, mean titers of 4200 and 640, respectively, p < 0.01). As expected, antibody titers for total IgG, IgG1, and IgG2a increase 14 days post-secondary immunization compared to 14 days post-primary immunization, and the significant effect of adjuvant addition to the blank liposome + antigen remains for total IgG (p < 0.05) and IgG2a antibody titers (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 4B, D, F). Interestingly, the differences in the humoral response between admixed and co-encapsulated liposomal CRX-601 and UM-3004 that were seen at the 14 days post-primary timepoint are lessened at the 14 days post-secondary timepoint (comparing Fig. 4E to F). Addition of admixed or co-encapsulated TLR4 and TLR7/8 agonists to A/Vic antigen results in a statistically significant 33- and 32-fold increases in IgG2a when compared to antigen and blank liposomes (Fig. 4F). While the IgG2a response to UM-3004 + antigen shows an increasing trend, this response is not statistically significant when compared to blank liposome + antigen (Fig. 4F).

Taken together, these data demonstrate that co-encapsulation of TLR4 and TLR7/8 agonists within the bilayer of a liposome can promote antigen-specific IgG2a responses indicative of Th1-type immunity [68]. This corroborates with previous literature demonstrating increased Th1-type responses in formulations that co-deliver TLR4 and TLR7/8 agonists [29], [30], [33], [44]. Since IL-12p70 is a key cytokine to enhance a Th1-type immune response [32], [65], [69], a boost in antigen specific Th1 type IgG2a antibody titers were expected in all formulations producing IL-12p70. Further, this boost may be even more pronounced in a different murine system since BALB/c mice have Th2-biased immune responses [70].

While IgG1 responses in mice are indicative of a Th2-type immune response and can lead to virus particle neutralization by preventing hemagglutinin (HA) binding and cellular entry, IgG2a antibody production leads to superior viral clearance and clearance of virus infected cells [71]. Virus neutralization can be used to predict influenza vaccine efficacy as measured by HA inhibition (HI) assays [72], [73], but protective anti-influenza immunity has been described in the absence of detectable HA neutralizing antibodies in both mice [74], [75] and humans [76], [77], and high virus neutralization does not always correlate with survival in mouse challenge models [71] or humans [72]. In an H1N1 pandemic strain of influenza, antibodies targeting non-HA neutralizing epitopes have been reported to be more effective mediators of immunity to infection than other antibody subtypes. For instance, vaccinating to increase influenza-specific IgG2a but not IgG1 production leads to less weight loss and lower viral titers in lung tissue of mice [78]. Since TLR4, TLR7/8 co-encapsulated liposomes lead to significantly improved total IgG and IgG2a titers, this formulation strategy could lead to superior protection compared to the current unadjuvanted seasonal influenza vaccine. Additionally, since responses were increased after a single vaccination, co-encapsulation strategies should be explored to increase early protection against influenza, which could hasten immunization in an emergency pandemic influenza setting.

Importantly, suboptimal doses of UM-3004 and CRX-601 were used in order to highlight TLR4 and TLR7/8 synergy as measured by IgG2a antibody production. As such, only 0.15 μg (0.10 nmol) CRX-601 was used in combination with 1.0 μg (0.85 nmol) UM-3004. In previous in vivo studies using other respective TLR4 and TLR7/8 synthetic agonists GLA with IMQ [30] or 3M-052 [43], [44] and 1Z105 with 1V270 [33], [40], all groups report synergy driven Th1-type responses, though agonist dosing varies. Fox et al. dose GLA at 5.0 μg (2.8 nmol) and IMQ at 20 μg (83 nmol) [30], which represent an approximately 83-fold molar increase in dose compared to CRX-601 and 28-fold molar increase compared to UM-3004. When using the more potent lipidated TLR7/8 agonist 3M-052 in place of IMQ, Abhyankar et al. use 1.0–2.0 μg of 3M-052 (1.7–3.4 nmol) though this still represents a 2 to 4-fold increase when compared to UM-3004. Lastly, Goff et al. dose the synthetic TLR4 agonist 1Z105 at 89.4 μg (200 nmol) and TLR7/8 agonist 1V270 at 10.8 μg (10 nmol), which represent respective 2000-fold and 12-fold increases when compared to CRX-601 and UM-3004. Comparatively, these studies report TLR7/8:TLR4 molar ratios of 29:1 [30], 1:1.4 [43], [44], and 1:20 [33], [40], which demonstrates synergy can be driven by varying molar ratios of TLR7/8 to TLR4 agonists. In vitro results in hPBMCs support this observation, as all TLR7/8:TLR4 ratios from 1.5:1 to 1:135 result in synergistic production of IL-12p70 (Figure 3). Since decreasing the amount of CRX-601 while UM-3004 was held constant did not abolish IL-12p70 production, this additionally demonstrates the high potency of the TLR4 agonist CRX-601. Though not explored here, further studies could elucidate the minimum doses of TLR4 and TLR7/8 agonists necessary for vaccine efficacy, which could lead to dose sparing and cost savings of not only TLR agonists but also antigen.

Finally, though co-encapsulation of lipidated TLR4 and TLR7/8 agonists within a liposome has been previously demonstrated to drive a Th1-type immune response [44], these are the first results to directly compare co-encapsulated liposomes to liposomal admixtures. Unexpectedly, TLR4 and TLR7/8 agonist co-encapsulated liposomes not only boost Th1-type humoral responses but also provide a superior early response compared to equimolar amounts of agonists delivered as liposomal admixtures. Though effects of co-encapsulating TLR4 and TLR7/8 agonists on downstream signaling or immune kinetics have not been elucidated here, co-encapsulation may offer superior early response by dual stimulation of receptors residing within the same cell and the same endosome since agonists are incorporated within the same particle. Due to spatial and temporal restraints on TLR4, TLR7/8 synergy [29], [39], formulating agonists within the bilayer of the same liposomal particle may provide a delivery advantage over admixtures since every particle is capable of TLR4 and TLR7/8 dual-agonism from the same cell.

Overall, liposomal co-encapsulation of lipidated TLR4 and TLR7/8 agonists is an adjuvant formulation strategy that leads to superior early IgG2a-biased influenza-specific humoral responses. Our data demonstrate that innate responses and adaptive immune response can be altered by changing the adjuvant formulation strategy without altering the components included in the adjuvant. Formulation strategies that achieve synergistic immune responses through strategic combinations of innate immune agonists could result in more potent and efficacious subunit vaccines. Further, these data suggest that co-encapsulation of TLR4 and TLR7/8 agonist lead to a more rapid increase in Th1-type humoral immunity following a single vaccination, which may be essential to immunization in an influenza pandemic setting. This rapid induction of immunity could lead to reduced disease burden, dose sparing, and more cost-effective vaccines.

4.0. Conclusions

We have identified an optimal liposomal composition for the effective incorporation of CRX-601, a TLR4 agonist, and UM-3004, a lipidated TLR7/8 agonist. Co-encapsulation of the agonists results in liposomes of sterile filterable size, customizable ratio of TLR4 to TLR7/8 agonist, and significantly increased agonist incorporation compared to non-lipidated agonists. Further, co-encapsulated liposomes can drive synergistic IL-12p70 production in vitro in hPBMCs where single agonists showed no response. When administered in vivo, co-encapsulation can drive a rapid Th1-type humoral immune response marked by a rapidly increased IgG2a output when compared to single agonist liposomes. In this fashion, liposomal co-encapsulation can be used as a versatile tool for tunable, efficacious delivery of TLR4 and lipidated TLR7/8 agonists with promising activity when an early immune response is necessary, for instance as an adjuvant for a subunit vaccine against pandemic influenza and may result in dose sparing of vaccine components.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors greatly thank Mark Livesay and Laura Bess for synthesizing TLR compounds for this work, and Margaret Whitacre, Robert Child, and Alyson Smith for their technical assistance with immunology studies and data analysis. GlaxoSmithKline Vaccines kindly provided the influenza antigen for this study. This work was supported in part by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) Adjuvant Discovery Contract [HHSN272200900036C] and by the Center for Translational Medicine at University of Montana. Any opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NIAID.

Abbreviations

- ACN

acetonitrile

- AGP

aminoalkyl glucosaminide 4-phosphate

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- CMOS

complementary metal-oxide semiconductor

- DAMP

danger associated molecular pattern

- DCs

dendritic cells

- DLS

dynamic light scattering

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- DOPC

1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- DPPC

1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- DSPC

1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- EM

electron microscopy

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- GLA

glucopyranosyl lipid adjuvant

- HA

hemagglutinin

- HHS

United States Department of Health and Human Services

- HRP

horseradish peroxidase

- IACUC

Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee

- IFNα

interferon α

- IL

interleukin

- IQ

imidazoquinoline

- IMQ

imiquimod

- IRB

Institutional Review Board

- ISGs

interferon stimulated genes

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- MPL

monophosphoryl lipid A

- NIH

National Institutes of Health

- OA

oxoadenine

- OD

optical density

- PAMP

pathogen associated molecular pattern

- hPBMCs

human peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- PDI

polydispersity

- PLGA

poly(lactic co-glycolic acid)

- PRR

pattern recognition receptor

- PVDF

polyvinylidene fluoride

- ROI

region of interest

- RP-HPLC

reverse phase-high performance liquid chromatography

- RPMI

Roswell Park Memorial Institute

- TBAOH

tetrabutylammonium hydroxide

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor α

- TLR

toll-like receptor

- TMB

3,3, 5,5’-tetramethylbenzidine

- TRIF

TIR domain-containing adaptor protein inducing interferon beta

- WFI

sterile water for irrigation

- UM

University of Montana

- UV/Vis

ultraviolet/visible spectrum

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Sulczewski FB, Liszbinski RB, Romão PRT, and Rodrigues Junior LC, “Nanoparticle vaccines against viral infections,” Arch Virol, May 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Nanjappa SG and Klein BS, “Vaccine immunity against fungal infections,” Current Opinion in Immunology, vol. 28, pp. 27–33, Jun. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Jacob SS, Cherian S, Sumithra TG, Raina OK, and Sankar M, “Edible vaccines against veterinary parasitic diseases—Current status and future prospects,” Vaccine, vol. 31, no. 15, pp. 1879–1885, Apr. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Brito LA and O’Hagan DT, “Designing and building the next generation of improved vaccine adjuvants,” J Control Release, vol. 190, pp. 563–79, Sep. 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Montomoli E, Piccirella S, Khadang B, Mennitto E, Camerini R, and Rosa AD, “Current adjuvants and new perspectives in vaccine formulation,” Expert Review of Vaccines, vol. 10, no. 7, pp. 1053–1061, Jul. 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Oleszycka E and Lavelle EC, “Immunomodulatory properties of the vaccine adjuvant alum,” Current Opinion in Immunology, vol. 28, pp. 1–5, Jun. 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].O’Hagan DT, Ott GS, De Gregorio E, and Seubert A, “The mechanism of action of MF59 – An innately attractive adjuvant formulation,” Vaccine, vol. 30, no. 29, pp. 4341–4348, Jun. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Garçon N, Vaughn DW, and Didierlaurent AM, “Development and evaluation of AS03, an Adjuvant System containing α-tocopherol and squalene in an oil-in-water emulsion,” Expert Review of Vaccines, vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 349–366, Jan. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Rosewich M, Lee D, and Zielen S, “Pollinex Quattro: An innovative four injections immunotherapy In allergic rhinitis,” Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, vol. 9, no. 7, pp. 1523–1531, Jul. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Coccia M et al. , “Cellular and molecular synergy in AS01-adjuvanted vaccines results in an early IFNγ response promoting vaccine immunogenicity,” NPJ Vaccines, vol. 2, Sep. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Garçon N, Segal L, Tavares F, and Van Mechelen M, “The safety evaluation of adjuvants during vaccine development: The AS04 experience,” Vaccine, vol. 29, no. 27, pp. 4453–4459, Jun. 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Campbell JD, “Development of the CpG Adjuvant 1018: A Case Study,” in Vaccine Adjuvants: Methods and Protocols, Fox CB, Ed. New York, NY: Springer New York, 2017, pp. 15–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Herzog C et al. , “Eleven years of Inflexal® V—a virosomal adjuvanted influenza vaccine,” Vaccine, vol. 27, no. 33, pp. 4381–4387, Jul. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kawasaki T and Kawai T, “Toll-like receptor signaling pathways,” Frontiers in immunology, vol. 5, p. 461, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Parker LC, Prince LR, and Sabroe I, “Translational Mini-Review Series on Toll-like Receptors: Networks regulated by Toll-like receptors mediate innate and adaptive immunity,” Clin Exp Immunol, vol. 147, no. 2, pp. 199–207, Feb. 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ulrich JT and Myers KR, “Monophosphoryl lipid A as an adjuvant. Past experiences and new directions,” Pharm Biotechnol, vol. 6, pp. 495–524, 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Evans JT, Cluff CW, Johnson DA, Lacy MJ, Persing DH, and Baldridge JR, “Enhancement of antigen-specific immunity via the TLR4 ligands MPL adjuvant and Ribi.529,” Expert. Rev. Vaccines, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 219–229, Apr. 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Spinner JL et al. , “Methylglycol chitosan and a synthetic TLR4 agonist enhance immune responses to influenza vaccine administered sublingually,” Vaccine, vol. 33, no. 43, pp. 5845–5853, Oct. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Oberoi HS, Yorgensen YM, Morasse A, Evans JT, and Burkhart DJ, “PEG modified liposomes containing CRX-601 adjuvant in combination with methylglycol chitosan enhance the murine sublingual immune response to influenza vaccination,” Journal of Controlled Release, vol. 223, pp. 64–74, October 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Garçon N and Pasquale AD, “From discovery to licensure, the Adjuvant System story,” Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 19–33, Jan. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Bazin HG et al. , “The ‘Ethereal’ nature of TLR4 agonism and antagonism in the AGP class of lipid A mimetics,” Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett, vol. 18, no. 20, pp. 5350–5354, Oct. 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Johnson DA et al. , “Synthesis and biological evaluation of a new class of vaccine adjuvants: Aminoalkyl glucosaminide 4-phosphates (AGPs),” Bioog. Med. Chem. Lett, vol. 9, no. 15, pp. 2273–2278, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Stover AG et al. , “Structure-activity relationship of synthetic toll-like receptor 4 agonists,” J. Biol. Chem, vol. 279, no. 6, pp. 4440–4449, Feb. 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Shukla NM et al. , “Toward self-adjuvanting subunit vaccines: model peptide and protein antigens incorporating covalently bound toll-like receptor-7 agonistic imidazoquinolines,” Bioorg Med Chem Lett, vol. 21, no. 11, pp. 3232–6, Jun. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Bazin HG et al. , “Structural requirements for TLR7-selective signaling by 9-(4-piperidinylalkyl)-8-oxoadenine derivatives,” Bioorg Med Chem Lett, vol. 25, no. 6, pp. 1318–23, Mar. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Smith AJ et al. , “Evaluation of novel synthetic TLR7/8 agonists as vaccine adjuvants,” Vaccine, vol. 34, no. 36, pp. 4304–4312, Aug. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Smirnov D, Schmidt JJ, Capecchi JT, and Wightman PD, “Vaccine adjuvant activity of 3M-052: An imidazoquinoline designed for local activity without systemic cytokine induction,” Vaccine, vol. 29, no. 33, pp. 5434–5442, Jul. 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Szeimies R-M, Bichel J, Ortonne J-P, Stockfleth E, Lee J, and Meng T-C, “A phase II dose-ranging study of topical resiquimod to treat actinic keratosis,” British Journal of Dermatology, vol. 159, no. 1, pp. 205–210, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Napolitani G, Rinaldi A, Bertoni F, Sallusto F, and Lanzavecchia A, “Selected Toll-like receptor agonist combinations synergistically trigger a T helper type 1-polarizing program in dendritic cells,” Nat. Immunol, vol. 6, no. 8, pp. 769–776, Aug. 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Fox CB et al. , “A nanoliposome delivery system to synergistically trigger TLR4 AND TLR7,” J. Nanobiotechnology, vol. 12, no. 1477–3155 (Electronic), p. 17, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Hsieh CS, Macatonia SE, Tripp CS, Wolf SF, O’Garra A, and Murphy KM, “Development of TH1 CD4+ T cells through IL-12 produced by Listeria-induced macrophages,” Science, vol. 260, no. 5107, pp. 547–549, Apr. 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Macatonia SE et al. , “Dendritic cells produce IL-12 and direct the development of Th1 cells from naive CD4+ T cells.,” The Journal of Immunology, vol. 154, no. 10, pp. 5071–5079, May 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Goff PH et al. , “Synthetic Toll-Like Receptor 4 (TLR4) and TLR7 Ligands as Influenza Virus Vaccine Adjuvants Induce Rapid, Sustained, and Broadly Protective Responses,” J Virol, vol. 89, no. 6, pp. 3221–3235, Jan. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Dowling DJ, “Recent Advances in the Discovery and Delivery of TLR7/8 Agonists as Vaccine Adjuvants,” ImmunoHorizons, vol. 2, no. 6, pp. 185–197, Jul. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Kasturi SP et al. , “Programming the magnitude and persistence of antibody responses with innate immunity,” Nature, vol. 470, no. 7335, pp. 543–547, Feb. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Yamamoto M et al. , “TRAM is specifically involved in the Toll-like receptor 4–mediated MyD88-independent signaling pathway,” Nature Immunology, vol. 4, no. 11, pp. 1144–1150, Nov. 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Saitoh S-I, “Chaperones and transport proteins regulate TLR4 trafficking and activation,” Immunobiology, vol. 214, no. 7, pp. 594–600, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Heil F et al. , “The Toll-like receptor 7 (TLR7)-specific stimulus loxoribine uncovers a strong relationship within the TLR7, 8 and 9 subfamily,” European Journal of Immunology, vol. 33, no. 11, pp. 2987–2997, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Deguine J and Barton GM, “MyD88: a central player in innate immune signaling,” F1000Prime Rep, vol. 6, Nov. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Goff PH et al. , “Synthetic Toll-Like Receptor 4 (TLR4) and TLR7 Ligands Work Additively via MyD88 To Induce Protective Antiviral Immunity in Mice,” J Virol, vol. 91, no. 19, Sep. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Yamamoto M et al. , “Role of Adaptor TRIF in the MyD88-Independent Toll-Like Receptor Signaling Pathway,” Science, vol. 301, no. 5633, pp. 640–643, Aug. 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Ebrahimian M et al. , “Co-delivery of Dual Toll-Like Receptor Agonists and Antigen in Poly(Lactic-Co-Glycolic) Acid/Polyethylenimine Cationic Hybrid Nanoparticles Promote Efficient In Vivo Immune Responses,” Front Immunol, vol. 8, Sep. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Abhyankar MM, Noor Z, Tomai MA, Elvecrog J, Fox CB, and Petri WA, “Nanoformulation of synergistic TLR ligands to enhance vaccination against Entamoeba histolytica,” Vaccine, vol. 35, no. 6, pp. 916–922, Feb. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Abhyankar MM et al. , “Adjuvant composition and delivery route shape immune response quality and protective efficacy of a recombinant vaccine for Entamoeba histolytica,” npj Vaccines, vol. 3, no. 1, p. 22, Jun. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Wilkinson A, Lattmann E, Roces CB, Pedersen GK, Christensen D, and Perrie Y, “Lipid conjugation of TLR7 agonist Resiquimod ensures co-delivery with the liposomal Cationic Adjuvant Formulation 01 (CAF01) but does not enhance immunopotentiation compared to non-conjugated Resiquimod+CAF01,” Journal of Controlled Release, vol. 291, pp. 1–10, Dec. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Lal H et al. , “Efficacy of an Adjuvanted Herpes Zoster Subunit Vaccine in Older Adults,” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 372, no. 22, pp. 2087–2096, May 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Maroof A, Yorgensen YM, Li Y, and Evans JT, “Intranasal Vaccination Promotes Detrimental Th17-Mediated Immunity against Influenza Infection,” PLOS Pathogens, vol. 10, no. 1, p. e1003875, Jan. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Bulbake U, Doppalapudi S, Kommineni N, and Khan W, “Liposomal Formulations in Clinical Use: An Updated Review,” Pharmaceutics, vol. 9, no. 2, Mar. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Garçon N and Mechelen MV, “Recent clinical experience with vaccines using MPL- and QS-21-containing Adjuvant Systems,” Expert Review of Vaccines, vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 471–486, Apr. 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Bazin HG, Bess LS, Livesay MT, Mwakwari SC, and Johnson DA, “Phospholipidation of TLR7/8-active imidazoquinolines using a tandem phosphoramidite method,” Tetrahedron Letters, vol. 57, no. 19, pp. 2063–2066, May 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Zhang H, “Thin-Film Hydration Followed by Extrusion Method for Liposome Preparation,” in Liposomes, Humana Press, New York, NY, 2017, pp. 17–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Schindelin J et al. , “Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis,” Nature Methods, vol. 9, no. 7, pp. 676–682, Jul. 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Stetefeld J, McKenna SA, and Patel TR, “Dynamic light scattering: a practical guide and applications in biomedical sciences,” Biophys Rev, vol. 8, no. 4, pp. 409–427, Oct. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Bhattacharjee S, “DLS and zeta potential – What they are and what they are not?,” Journal of Controlled Release, vol. 235, pp. 337–351, Aug. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Anderson M and Omri A, “The Effect of Different Lipid Components on the In Vitro Stability and Release Kinetics of Liposome Formulations,” Drug Delivery, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 33–39, Jan. 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Immordino ML, Dosio F, and Cattel L, “Stealth liposomes: review of the basic science, rationale, and clinical applications, existing and potential,” Int J Nanomedicine, vol. 1, no. 3, pp. 297–315, Sep. 2006. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Vaure C and Liu Y, “A Comparative Review of Toll-Like Receptor 4 Expression and Functionality in Different Animal Species,” Front Immunol, vol. 5, Jul. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Dowling DJ et al. , “TLR7/8 adjuvant overcomes newborn hyporesponsiveness to pneumococcal conjugate vaccine at birth,” JCI Insight, vol. 2, no. 6, p. e91020, Mar. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Gorden KB et al. , “Synthetic TLR Agonists Reveal Functional Differences between Human TLR7 and TLR8,” The Journal of Immunology, vol. 174, no. 3, pp. 1259–1268, Feb. 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Dai J, Megjugorac NJ, Amrute SB, and Fitzgerald-Bocarsly P, “Regulation of IFN Regulatory Factor-7 and IFN-α Production by Enveloped Virus and Lipopolysaccharide in Human Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells,” The Journal of Immunology, vol. 173, no. 3, pp. 1535–1548, Aug. 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Schoggins JW and Rice CM, “Interferon-stimulated genes and their antiviral effector functions,” Current Opinion in Virology, vol. 1, no. 6, pp. 519–525, Dec. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Aarreberg LD et al. , “Interleukin-1β Signaling in Dendritic Cells Induces Antiviral Interferon Responses,” mBio, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. e00342–18, May 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Kopitar-Jerala N, “The Role of Interferons in Inflammation and Inflammasome Activation,” Front Immunol, vol. 8, Jul. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Man SM and Kanneganti T-D, “Regulation of inflammasome activation,” Immunological Reviews, vol. 265, no. 1, pp. 6–21, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].O’Garra A and Murphy KM, “From IL-10 to IL-12: how pathogens and their products stimulate APCs to induce TH1 development,” Nature Immunology, vol. 10, pp. 929–932, Sep. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Ouyang X, Negishi H, Takeda R, Fujita Y, Taniguchi T, and Honda K, “Cooperation between MyD88 and TRIF pathways in TLR synergy via IRF5 activation,” Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun, vol. 354, no. 4, pp. 1045–1051, Mar. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Akira S, Uematsu S, and Takeuchi O, “Pathogen Recognition and Innate Immunity,” Cell, vol. 124, no. 4, pp. 783–801, Feb. 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Germann T et al. , “Interleukin-12 profoundly up-regulates the synthesis of antigen-specific complement-fixing IgG2a, IgG2b and IgG3 antibody subclasses in vivo,” European Journal of Immunology, vol. 25, no. 3, pp. 823–829, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Gee K, Guzzo C, Mat NFC, and W. M, and Kumar A, “The IL-12 Family of Cytokines in Infection, Inflammation and Autoimmune Disorders,” Inflammation & Allergy - Drug Targets (Discontinued), 28-February-2009. [Online]. Available:http://www.eurekaselect.com/84104/article. [Accessed: 19-Oct-2018]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Watanabe H, Numata K, Ito T, Takagi K, and Matsukawa A, “Innate immune response in Th1- and Th2-dominant mouse strains.,” Shock, vol. 22, no. 5, pp. 460–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Huber VC et al. , “Distinct Contributions of Vaccine-Induced Immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) and IgG2a Antibodies to Protective Immunity against Influenza,” Clin Vaccine Immunol, vol. 13, no. 9, pp. 981–990, Sep. 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Hobson D, Curry RL, Beare AS, and Ward-Gardner A, “The role of serum haemagglutination-inhibiting antibody in protection against challenge infection with influenza A2 and B viruses,” J Hyg (Lond), vol. 70, no. 4, pp. 767–777, Dec. 1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].de Jong JC, Palache AM, Beyer WEP, Rimmelzwaan GF, Boon ACM, and Osterhaus ADME, “Haemagglutination-inhibiting antibody to influenza virus,” Dev Biol (Basel), vol. 115, pp. 63–73, 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Kodihalli S, Haynes JR, Robinson HL, and Webster RG, “Cross-protection among lethal H5N2 influenza viruses induced by DNA vaccine to the hemagglutinin.,” J Virol, vol. 71, no. 5, pp. 3391–3396, May 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Kodihalli S, Goto H, Kobasa DL, Krauss S, Kawaoka Y, and Webster RG, “DNA Vaccine Encoding Hemagglutinin Provides Protective Immunity against H5N1 Influenza Virus Infection in Mice,” J Virol, vol. 73, no. 3, pp. 2094–2098, Mar. 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Belshe RB et al. , “Correlates of Immune Protection Induced by Live, Attenuated, Cold-Adapted, Trivalent, Intranasal Influenza Virus Vaccine,” J Infect Dis, vol. 181, no. 3, pp. 1133–1137, Mar. 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Clements ML, Betts RF, Tierney EL, and Murphy BR, “Serum and nasal wash antibodies associated with resistance to experimental challenge with influenza A wild-type virus.,” Journal of Clinical Microbiology, vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 157–160, Jul. 1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Bungener L, Geeraedts F, ter Veer W, Medema J, Wilschut J, and Huckriede A, “Alum boosts TH2-type antibody responses to whole-inactivated virus influenza vaccine in mice but does not confer superior protection,” Vaccine, vol. 26, no. 19, pp. 2350–2359, May 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.