Abstract

Megalin is a member of the low-density lipoprotein receptor superfamily. It has been recognized as an endocytic receptor for a large spectrum of ligands. As a consequence, megalin regulates homeostasis of many molecules and affects multiple physiological and pathophysiological functions. The renin-angiotensin system is a hormonal system. A number of studies have reported contributions of the renin-angiotensin system to atherosclerosis. There is evolving evidence that megalin is a regulator of the renin-angiotensin system, and contributes to atherosclerosis. This brief review provides contemporary insights into effects of megalin on renal functions, the renin-angiotensin system, and atherosclerosis.

Keywords: megalin, kidney, renin angiotensin system, atherosclerosis

Introduction

Megalin is a large transmembrane glycoprotein that was initially called gp330 [1], and is also known as low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 2 (LRP2) [2-4]. It was discovered in early 1980s as a pathogenic antigen of Heymann nephritis [1], implicating its important role in renal functions. Megalin is also involved in the endocytosis of many substances such as lipoproteins, proteins, and drugs in proximal tubular cells(PTCs) of kidney. The multi-ligand interactions of megalin implies its contribution to renal-based physiology and pathophysiology.

The renin-angiotensin system (RAS) is a coordinated hormonal cascade that regulates renal and cardiovascular functions and contributes to multiple diseases. The RAS is composed of multiple molecules. Angiotensinogen (AGT) is the substrate, which is cleaved by two enzymes, renin and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), to produce angiotensin II (AngII). AngII is a major effector of the RAS, and acts predominantly via AngII type 1 receptors (AT1R in human and AT1aR in mouse). There is accumulating evidence that megalin-mediated endocytosis in renal PTCs is related to regulation of the RAS. Recently, effects of megalin on atherosclerosis were reported [5]. Pharmacological inhibition of megalin attenuated atherosclerosis formation with increased urinary excretion of AGT and renin [5]. This is a novel finding to connect megalin, the RAS, and atherosclerosis. We will review the current knowledge on physiological and pathophysiological functions of megalin on kidney, and explore new concepts of its contributions to the renal RAS and atherosclerosis.

2. Molecular characteristics of megalin

Characteristics of megalin in human, rat, and mouse are described in Table 1. The full-length sequence of megalin in human was identified in 1990s [6-8]. Transcription length and molecular weight are similar among species [9]. The amino acid sequence is 94% identical between mouse and rat, and 77% identical between human and rat or mouse. This high conservation among species makes rodents, especially mouse, a valuable animal model to investigate the physiology and pathophysiology of megalin.

Table 1.

Characteristics of megalin in human and rodents

| Chromo some |

Exo ns |

Transcript length (bp) |

Translation length (aa) |

Signal peptide (aa) |

Molecular weight (kDa) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human | 2 | 79 | 15657 | 4655 | 1 - 25 | 522 |

| Rat | 3 | 79 | 15512 | 4660 | 1 - 25 | 519 |

| Mouse | 2 | 79 | 15460 | 4660 | 1 - 25 | 519 |

Megalin has one extracellular domain with 4 clusters of cysteine-rich complement-type repeats, a single transmembrane domain (23 amino acids), and an intracellular C-terminal cytoplasmic tail of 209 amino acids in human [2, 3, 8]. The extracellular domain is predicted to be involved in ligand bindings and the cytoplasmic domain may regulate receptor trafficking and endocytosis Two NPxY motifs at the cytoplasmic tail in human have been proposed to mediate apical sorting, endocytosis, and intracellular signaling [2, 10]. Rat has an NPxY-like motif as well as two NPxY motifs. The intracellular C-terminal cytoplasmic tail can be cleaved by γ-secretase and the C-terminal fragment is thought to influence gene transcription of proteins such as megalin itself and Na+/H+ exchanger (NHE3) [11, 12]. Detailed information on the structure and ligands of megalin has been provided by several elegant reviews [2, 3, 13, 14].

3. Gene mutations of megalin and organ development

During the embryonic development, megalin is expressed in the trophectoderm, maternal-fetal interface, and epithelium-dominant tissues [15, 16]. It is also present in the second heart field, neural crest, endocardium, epicardium, and mesothelium [17].

Donnai-Barrow syndrome is a rare autosomal recessive disorder caused by mutations of megalin [18]. Most mutations in this syndrome are predicted to be loss-of-function. This syndrome is characterized by craniofacial dysmorphology, ophthalmological abnormalities, and ocular complications. Low molecular proteinuria and focal glomerulosclerosis have also been reported in patients with Donnai-Barrow syndrome. In addition, a few cases of Donnai-Barrow syndrome show congenital heart diseases, such as ventricular septal defect and patent ductus arteriosus [17].

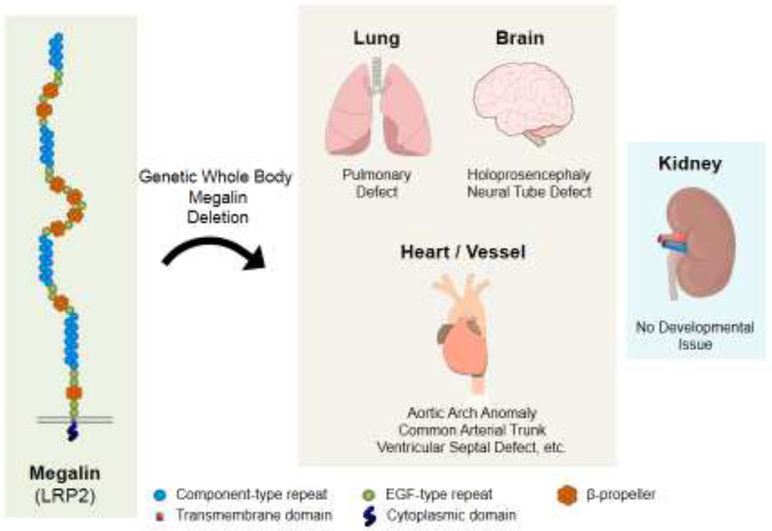

Whole body megalin deficient mice were developed by Willnow and colleagues [19, 20]. These mice have provided insights into understanding multiple megalin-related functions and their relevant human conditions. Constitutive whole body megalin deficient mice exhibit several developmental abnormalities (Figure 1). Homozygous global megalin deletion causes emphysematous lung from E9.5. As a consequence, most megalin deficient mice die perinatally due to respiratory insufficiency [19]. Megalin deficient mice that survive postnatally have neurological malformation such as holoprosencephaly and neural tube defects [15, 16, 19]. Comprehensive characterization of mouse embryos between E10.5 and E15.5 demonstrated that megalin deficiency resulted in cardiovascular deformities including aortic arch anomaly, common arterial trunk (persistent truncus arteriosus) with coronary artery anomaly, ventricular septal defect, overriding of the tricuspid valve, and thinning of the ventricular myocardium [21]. These findings provide compelling evidence that megalin is crucial for lung, neural, and cardiovascular developments.

Figure 1. Roles of megalin during embryonic development.

Whole body deletion of megalin leads to lung insufficiency, neurological complications, and cardiovascular abnormalities during embryonic development, but has no apparent effects on renal development [14-16, 19, 21].

4. Roles of megalin on renal function and renal diseases

4.1. Megalin as an endocytic receptor in kidney

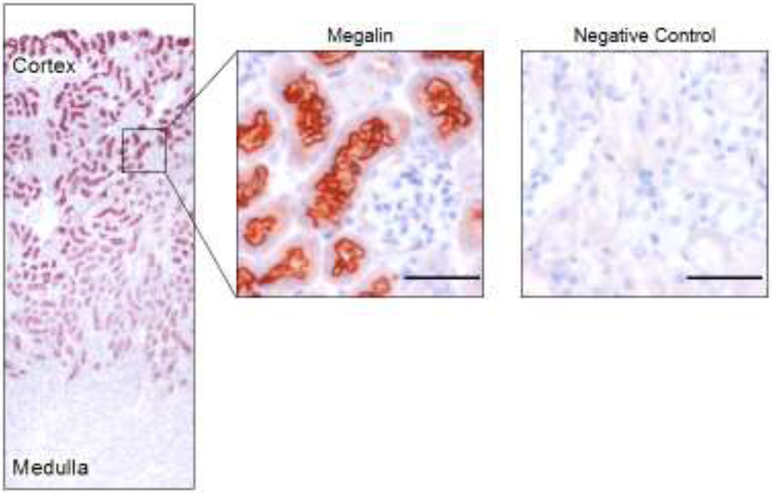

The human protein atlas describes that megalin is most abundant in kidney [22, 23]. Megalin is expressed in the brush border, endocytic vesicles, and dense apical tubule cells of renal proximal tubules [3], and podocytes of glomeruli as found in human and rats [24, 25]. The distribution pattern shows that megalin is most abundant in the outer cortex of proximal tubules, and gradually reduced in the medulla (Figure 2) [26, 27]. This distribution pattern is consistent with its pivotal role in reabsorption of molecules that have filtered through glomeruli.

Figure 2. Distribution pattern of megalin in proximal tubules.

Representative images of immunohistochemistry for megalin in a mouse kidney section. Red color represents positive immunostaining of megalin. Negative control was applied with an isotype matched non-immune IgG replacing megalin antibody. Scale bar = 50 μm.

Megalin is an endocytic and fast-recycling receptor for multiple ligands. A recent study has demonstrated that megalin defines the apical recycling pathway of epithelia, with common recycling endosomes as its apical sorting station [28]. Proteins filtered through glomeruli bind to megalin and the megalin-ligand complex is internalized into cells by endocytosis [8, 29, 30]. PTCs in the outer cortex have highly active endocytotic and lysosomal apparatus with the densest brush border membranes and a large number of mitochondria. Most ligands interact with megalin in PTCs of the outer cortex [31, 32]. Endosomes have chloride channels on their membrane, and chloride channel-induced acidification mediates disruption of megalin-ligand complex in endosomes. Ligands are subsequently degraded in lysosomes. Unbound megalin is recycled to the cell surface of PTCs [8, 29]. Some substances such as albumin and retinol binding protein are transported through the basal side of PTCs as a transcytosis [29, 33-35]. AGT, the unique substrate of the renin-angiotensin system, can also be transcytosed through megalin [30].

Cubilin is an extracellular protein in PTCs and interacts with megalin to form a multi-receptor complex driving endocytosis and transcytosis of some substances including albumin [3, 34-36]. The role of cubilin has been summarized by several excellent reviews [2, 3, 37, 38]. However, effects of cubilin on the renin-angiotensin system have not been reported.

4.2. Megalin-related renal disorders

Dent disease is a rare X-linked renal tubular disorder in human. Dent disease type 1 is caused by mutations in a renal chloride channel protein (CLCN5) [39]. CLCN5 is located on the membrane of early endosomes in PTCs and is essential for endosomal acidification, leading to disassembly of a megalin-ligand complex [40]. Therefore, mutations of CLCN5 cause defective recycling of megalin and loss of megalin at the apical membrane of PTCs. Due to impaired endocytosis of megalin, patients with Dent disease have increased urinary excretion of proteins such as albumin and α1-microglobulin [41]. AGT and renin are also excreted in urine in these patients [42]. Consistent with Dent disease in human, Clcn5 deletion in mice causes loss of megalin expression at brush borders of PTCs with impaired endocytosis and lysosomal processing of internalized ligands in PTCs [43]. Therefore, these mice exhibit proteinuria, consistent with what are found in human Dent disease.

Recently, a tubulointerstitial disease caused by autoimmune disorder against megalin was identified in human and named ABBA (kidney anti brush border antibodies and renal failure) disease [44]. Acute tubular injury with IgG deposition in tubular epithelium along the apical surface and basolateral basement membrane was found in kidney biopsies of these patients, which were associated with acute kidney injury and subnephrotic proteinuria.

Continuous damages of proximal tubules have also been reported to decrease megalin expression in PTCs. Two earlier studies reported that megalin was reduced in proximal tubules of diabetic rats [45, 46]. Subsequently, a human study reported that urinary excretion of full-length megalin was associated with the severity of diabetic nephropathy [47]. Loss of brush borders led to decreases of megalin expression in PTCs of patients with advanced diabetes. Extracellular vesicles might serve as a mediator for urinary excretion of megalin [48]. However, molecular mechanisms by which megalin is shed into urine has not been fully understood.

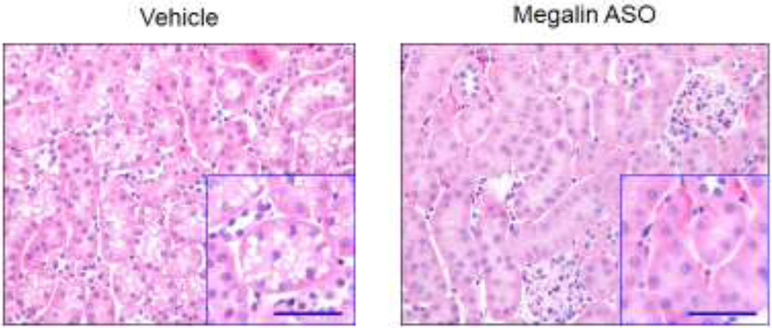

Megalin internalizes many substances such as lipoproteins, hormones, and enzymes by endocytosis in PTCs of kidney. Thus, megalin is important to the retention of many substances in PTCs. However, in patients with diabetic nephropathy or metabolic syndrome-related nephropathy, some nephrotoxic proteins or their carriers are also endocytosed by megalin into PTCs [49]. Excessive burden of the toxic substances in PTCs results in renal dysfunction and pathological changes. In addition to diabetes, obesity is reported to cause megalin-mediated pathological changes in kidney [50]. High fat diet (60% calories from fat) led to renal histological changes including proximal tubular cytosolic vacuolar formation and lipid peroxidation, interstitial fibrosis, and glomerular hypertrophy in C57BL/6J mice [50, 51]. These renal impairments were ameliorated by deletion of megalin in proximal tubules [50]. In low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor deficient mice, 12 weeks of Western diet (42% calories from saturated fat) feeding also caused cytosolic vacuolar formation that was attenuated by megalin inhibition using anti-sense oligonucleotides (ASO) (Figure 3). Several studies have provided compelling evidence that deletion of megalin in PTCs improves inflammatory response in mice with glomerular injury and suppresses nephrotoxicity induced by many drugs [52, 53]. Therefore, megalin in PTCs also has pathophysiological effects under certain abnormal conditions.

Figure 3. Inhibition of megalin ablates Western diet-induced proximal tubule pathology.

Hematoxylin-eosin staining was performed in kidney sections from LDL receptor deficient mice fed a Western diet (TD.88137, Envigo) for 12 weeks and administered either vehicle or megalin ASO. Cytosolic vacuolar formation in proximal tubules is abundant in mice injected with vehicle, but is not evident in mice injected with megalin ASO. Small boxes show higher magnification images. Scale bar = 50 μm.

4.3. Mouse models to investigate the role of megalin in PTCs

Since megalin is a multi-ligand endocytic receptor most abundant in PTCs, it would be expected that deletion of megalin in this cell type leads to profound kidney dysfunction. Global deletion of megalin exhibits proteinuria; however, renal dysfunction in these mice is mild [26, 54-57]. To understand the role of megalin in kidney, PTC-specific megalin deficient mice were generated. Initially, megalin floxed mice were bred to transgenic mice carrying a truncated human apolipoprotein (apo) E promoter to drive expression of the Cre. The apoE promoter-driven Cre led to deletion of megalin in PTCs in a mosaic pattern (~ 60% deletion) [20, 30]. In contrast to the high death rate and neurological defects of whole body megalin deficient mice, these mice had normal survival rate and normal growth. Therefore, this mouse model provides an optimal approach for determining the interaction of megalin and its ligands on proximal tubules, and has been a useful tool to study megalin on many pathophysiological effects in mice. To overcome the partial deletion of megalin induced by apoE promoter-driven Cre activity, PTC-specific megalin deficient mice were developed by breeding megalin floxed mice to Wnt4 promoter-EGFP-Cre transgenic mice or Ndrg1 promoter-CreERT2 mice (Table 2) [26, 57, 58]. Either promotor with Cre expression led to ~ 90% deletion of megalin in PTCs. Deletion of megalin in PTCs exhibits proteinuria including urinary excretion of vitamin D-binding protein, retinol-binding protein, α1-microglobulin, odorant-binding protein and albumin; an advanced renal dysfunction such as electrolyte imbalance and oliguria is noted in a small number of these mice [26, 54-57]. The modest renal phenotypes are evident in patients with Donnai-Barrow syndrome who carry megalin mutations, which implicates that megalin is not the only contributor to maintenance of renal proximal tubule physiological functions [17].

Table 2.

Phenotypes of mice with megalin depletion in proximal tubular cells

| Cre promot er |

Phenotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| ApoE | Hypocalcemia and osteopathy | (20) |

| Diminished injury markers (HO-1, MCP-1, and apoptosis) in mice with glomerular injury | (52) | |

| Increased urinary loss of angiotensinogen (AGT) | (30, 75) | |

| Increased excretion of hepcidin-1 in urine | (80) | |

| Improvement of the nephrotoxicity induced by gentamicin, colistin, vancomycin, and cisplatin | (53) | |

| Improved kidney structural and functional impairment induced by high fat diet | (51) | |

| Wnt4 | Increased albumin excretion in urine | (58) |

| Ndrg1 | Increased albumin and NGAL (neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin) excretion in urine | (26) |

| Increased excretion of FABP4 (fatty acid binding protein 4) in urine | (57) |

5. Interactions between megalin and the RAs on the development of atherosclerosis

5.1. Atherogenic effects of the RAS

As a systemic hormonal system, AGT is mainly produced in liver and renin is secreted from the juxtaglomerul apparatus of kidney [59-61]. Lung is an important source of ACE [62]. However, PTC itself has all of these components necessary to produce AngII. Therefore, PTCs can generate AngII locally [30]. In addition, AngII concentrations in PTCs are approximately 100 times greater than plasma concentrations [63, 64]. Furthermore, expression of AT1aR in PTCs is higher than in other cell types of kidney [65]. It has also been reported that increased AngII production in PTCs increases systolic blood pressure in mice [66]. These results support the notion that AngII produced in PTCs contributes to cardiovascular functions.

A number of human and animal studies have reported critical roles of the RAS, especially AngII through AT1aR, on atherosclerosis formation [61, 67-70]. AngII administration augments atherosclerosis, while whole body deletion of AT1aR attenuates atherosclerosis as demonstrated in multiple mouse studies [67-69]. However, where and how AngII and AT1aR interact to promote atherosclerosis are still undefined. Despite inhibition of atherosclerosis by whole body AT1aR deletion, deletion of AT1aR in major cellular components of atherosclerosis such as macrophages, endothelial cells, or smooth muscle cells did not reduce atherosclerosis [61, 71, 72]. It is possible that AT1aR acts remotely on atherosclerosis. Since PTCs generate AngII locally with high concentration and AT1aR is abundant on PTCs, it would be interesting in determining whether AngII and AT1aR in PTCs contribute to atherosclerosis.

5.2. Contribution of megalin to atherosclerosis through the renal RAS

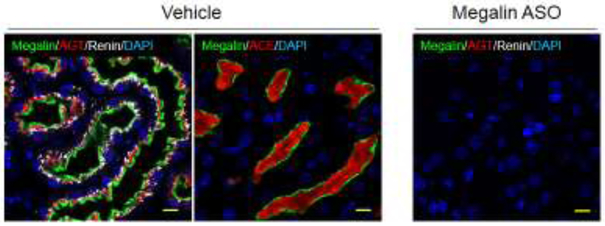

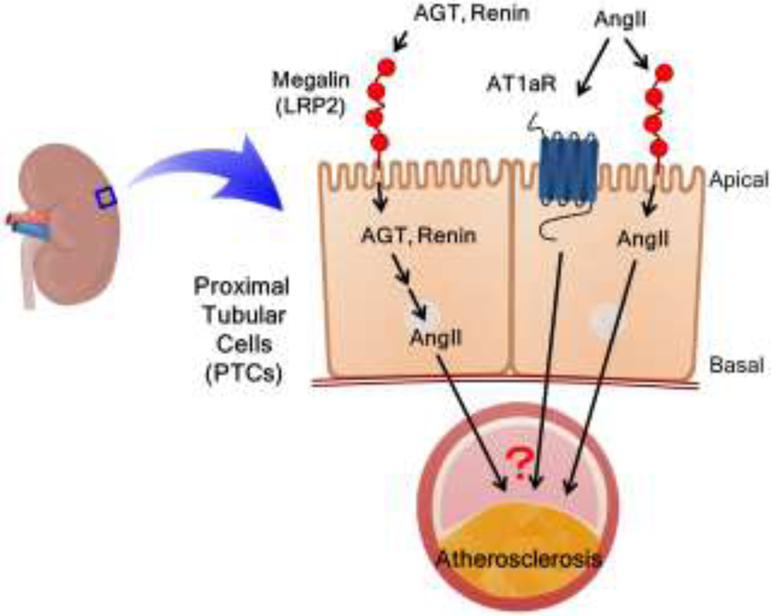

Megalin lies on the apical surface of proximal tubule cells. AGT and renin are endocytosed through megalin into PTCs. AGT is retained in endosomes and lysosomes of PTCs [30], and renin is expected to be located in subapical vesicles of PTCs [73, 74]. ACE is on the brush border membrane of PTCs (Figure 4) [5, 30]. In mice with mosaic deficiency of megalin, AGT and renin were detected only in PTCs expressing megalin [30]. Consistent with the findings in mice displaying a mosaic pattern of megalin deficiency in proximal tubules, anti-sense oligonucleotides (ASO) targeting megalin ablated accumulation of AGT and renin in PTCs (Figure 4) [5]. Therefore, megalin regulates the internalization of AGT and renin in PTCs. Hepatocyte-specific deletion of AGT decreased renal AngII concentration, and pharmacological inhibition of megalin also led to reduction of renal AngII concentration [5, 75]. Since megalin can internalize not only AGT and renin but AngII [76, 77], reduced renal AngII concentrations could be due to increased loss of AngII in urine attributed to inhibition of megalin. Although AT1aR is the major receptor to internalize AngII in PTCs, megalin contributes to ~ 30% of AngII internalization [77, 78]. Therefore, it is likely that inhibition of megalin reduces renal AngII concentration as a consequence of reduced uptake of AGT, renin, and AngII into PTCs.

Figure 4. Presence of megalin, angiotensinogen (AGT), renin, and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) in renal proximal tubules.

Immunofluorescent staining shows the location of megalin, AGT, renin, and ACE in proximal tubules of a mouse kidney section. In a mouse administered vehicle, megalin lies on the apical surface of proximal tubule cells, while AGT and renin are present intracellularly, and ACE is on the brush border membrane. Negative control (lack of megalin) is provided in a kidney section from a mouse administered megalin ASO. Megalin = green, AGT/ACE = red, renin = white, DAPI (nucleus) = blue. Scale bar = 10 μm. Images were adopted and modified from the authors’ publication [5].

Effect of megalin on the development of atherosclerosis has been reported recently. In LDL receptor deficient mice fed a Western diet, a classic mouse model to study atherosclerosis [79], vehicle or ASO targeting mouse megalin was administered to determine their effects on atherosclerosis. Although mice administered megalin ASO had comparable high plasma cholesterol concentrations to those administered vehicle, atherosclerotic lesion size was only 40 - 50% of the lesion size in mice injected with vehicle. No differences on blood pressure (an independent risk factor for atherosclerosis) or inflammation (a well-recognized mechanism of atherosclerosis) were found between mice administered vehicle and megalin ASO [5]. Mice with megalin ASO exhibited lower renal AngII concentrations than in vehicle mice, which is the only difference detected among the multiple parameters measured in this study. These findings support the concept that renal AngII, through a megalin-mediated mechanism in PTCs, contributes to atherosclerosis (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Proposed effects of megalin on the renal renin-angiotensin system and atherosclerosis.

Megalin is present on the apical surface of proximal tubule cells (PTCs) that regulates the homeostasis of AGT, renin, and AngII in PTCs. The process of these renin-angiotensin components in PTCs is proposed to contribute to the cross-talk between megalin and the renal RAS to promote atherosclerosis.

The study using megalin ASO revealed two novel findings. First, inhibition of megalin reduced hypercholesterolemia-induced atherosclerosis. Second, renal AngII concentration was associated with atherosclerosis formation. These findings support the potential importance of cross-talk among organs and tissues (liver, kidney, and aorta) on atherosclerosis development, and provide a potentially novel insight into the mechanism by which the RAS promotes atherosclerosis. Thus, it would be important to determine whether and how AngII in PTCs contribute to atherosclerosis formation through remote mechanisms (Figure 5). Availability of AT1aR floxed mice and PTC-specific Cre transgenic mice provides an optimal model to elucidate its mechanism. In addition, since AngII can be internalized through both AT1aR and megalin, exploring the interaction of these two receptors in PTCs on atherosclerosis may lead to defining novel mechanisms (Figure 5).

6. Summary and Perspectives

Megalin is expressed in the entire body during the prenatal phase and plays important roles in multiple organ development including brain, lung, heart, and vasculature. In the postnatal phase, megalin is most abundant in the kidney. Loss of function of megalin causes low-molecular weight proteinuria. Genetic deletion of megalin in PTCs or pharmacological inhibition of megalin improves renal injury-induced inflammation, drug-induced nephrotoxicity, and diabetic or diet-induced nephropathy, and reduces hypercholesterolemia-induced atherosclerosis, implicating that megalin contributes to cardiovascular and renal pathogenesis.

Pharmacological inhibitors of the classic renin-angiotensin components have been major therapeutics for renal and cardiovascular diseases including atherosclerosis. Inhibition of megalin also shows promising benefits on these pathological conditions in a hypercholesterolemic mouse model. It is important to understand mechanisms by which megalin and the renin-angiotensin system interact to promote cardiovascular and renal diseases. It is also important to determine whether targeting megalin and the RAS have synergistic beneficial effects in treating the related human diseases.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The authors’ research work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers R01HL133723 and R01HL139748 and the American Heart Association SFRN in Vascular Disease (18SFRN33960001). Hisashi Sawada is supported by an American Heart Association postdoctoral fellowship (18POST33990468). Megalin-related research work is supported by R01HL139748. The content in this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kerjaschki D, Farquhar MG. Immunocytochemical localization of the Heymann nephritis antigen (GP330) in glomerular epithelial cells of normal Lewis rats. J Exp Med. 157 (1983) 667–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christensen EI, Birn H. Megalin and cubilin: multifunctional endocytic receptors. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 3 (2002) 256–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nielsen R, Christensen EI, Birn H. Megalin and cubilin in proximal tubule protein reabsorption: from experimental models to human disease. Kidney Int. 89 (2016) 58–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marzolo MP, Farfan P. New insights into the roles of megalin/LRP2 and the regulation of its functional expression. Biol Res. 44 (2011) 89–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ye F, Wang Y, Wu C, Howatt DA, Wu CH, Balakrishnan A, Mullick AE, Graham MJ, Danser AHJ, Wang J, Daugherty A, Lu HS. Angiotensinogen and Megalin Interactions Contribute to Atherosclerosis-Brief Report. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 39 (2019) 150–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Korenberg JR, Argraves KM, Chen XN, Tran H, Strickland DK, Argraves WS. Chromosomal localization of human genes for the LDL receptor family member glycoprotein 330 (LRP2) and its associated protein RAP (LRPAP1). Genomics. 22 (1994) 88–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saito A, Pietromonaco S, Loo AK, Farquhar MG. Complete cloning and sequencing of rat gp330/"megalin," a distinctive member of the low density lipoprotein receptor gene family. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 91 (1994) 9725–9729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hjalm G, Murray E, Crumley G, Harazim W, Lundgren S, Onyango I, Ek B, Larsson M, Juhlin C, Hellman P, Davis H, Akerstrom G, Rask L, Morse B. Cloning and sequencing of human gp330, a Ca(2+)-binding receptor with potential intracellular signaling properties. Eur J Biochem. 239 (1996) 132–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.UniProt C. UniProt: a worldwide hub of protein knowledge. Nucleic Acids Res. 47 (2019) D506–D515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takeda T, Yamazaki H Farquhar MG. Identification of an apical sorting determinant in the cytoplasmic tail of megalin. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 284 (2003) C1105–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biemesderfer D. Regulated intramembrane proteolysis of megalin: linking urinary protein and gene regulation in proximal tubule? Kidney Int. 69 (2006) 1717–1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li Y, Cong R, Biemesderfer D. The COOH terminus of megalin regulates gene expression in opossum kidney proximal tubule cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 295 (2008) C529–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.willnov TE, Christ A. Endocytic receptor LRP2/megalin-of holoprosencephaly and renal Fanconi syndrome. Pflugers Arch. 469 (2017) 907–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kozyraki R, Cases O. Inherited LRP2 dysfunction in human disease and animal models. J Rare Dis Res Treat. 2 (2017) 22–31.30854528 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Assemat E, Chatelet F, Chandellier J, Commo F, Cases O, Verroust P, Kozyraki R. Overlapping expression patterns of the multiligand endocytic receptors cubilin and megalin in the CNS, sensory organs and developing epithelia of the rodent embryo. Gene Expr Patterns. 6 (2005) 69–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fisher CE, Howie SE. The role of megalin (LRP-2/Gp330) during development. Dev Biol. 296 (2006) 279–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pober BR, Longoni M, Noonan KM. A review of Donnai-Barrow and facio-oculo-acoustico-renal (DB/FOAR) syndrome: clinical features and differential diagnosis. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 85 (2009) 76–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kantarci S, Al-Gazali L, Hill RS, Donnai D, Black GC, Bieth E, Chassaing N, Lacombe D, Devriendt K, Teebi A, Loscertales M, Robson C, Liu T, MacLaughlin DT, Noonan KM, Russell MK, Walsh CA, Donahoe PK, Pober BR. Mutations in LRP2, which encodes the multiligand receptor megalin, cause Donnai-Barrow and facio-oculo-acoustico-renal syndromes. Nat Genet. 39 (2007) 957–959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Willnow TE, Hilpert J, Armstrong SA, Rohlmann A, Hammer RE, Burns DK, Herz J. Defective forebrain development in mice lacking gp330/megalin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 93 (1996) 8460–8464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leheste JR, Melsen F, Wellner M, Jansen P, Schlichting U, Renner-Muller I, Andreassen TT, Wolf E, Bachmann S, Nykjaer A, Willnow TE. Hypocalcemia and osteopathy in mice with kidney-specific megalin gene defect. Faseb j. 17 (2003) 247–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baardman ME, Zwier MV, Wisse LJ, Gittenberge-de Groot AC, Kerstjens-Frederikse WS, Hofstra RM, Jurdzinski A, Hierck BP Jongbloed MR, Berger RM, Plosch T, DeRuiter MC. Common arterial trunk and ventricular non-compaction in Lrp2 knockout mice indicate a crucial role of LRP2 in cardiac development. Dis Model Mech. 9 (2016) 413–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The Human Protein Atlas. LRP2. Protein Atlas version 19. Available from: https://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000081479-LRP2 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Uhlen M, Fagerberg L, Hallstrom BM, Lindskog C, Oksvold P, Mardinoglu A, Sivertsson A, Kampf C, Sjostedt E, Asplund A, Olsson I, Edlund K, Lundberg E, Navani S, Szigyarto CA, Odeberg J, Djureinovic D, Takanen JO, Hober S, Alm T, Edqvist PH, Berling H, Tege H, Mulder J, Rockberg J, Nilsson P, Schwenk JM, Hamsten M, von Feilitzen K, Fosberg M, Persson L, Johansson F, Zwahlen M, von Heijne G, Nielsen J, Ponten F. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science. 347 (2015) 1260419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prabakaran T, Nielsen R Larsen JV, Sorensen SS, Feldt-Rasmussen U, Saleem MA, Petersen CM, Verroust PJ, Christensen EI. Receptor-mediated endocytosis of alpha-galactosidase A in human podocytes in Fabry disease. PLoS One. 6 (2011) e25065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schiessl IM Hammer A, Kattler V, Gess B, Theilig F, Witzgall R, Castrop H. Intravital Imaging Reveals Angiotensin II-Induced Transcytosis of Albumin by Podocytes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 27 (2016) 731–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mori KP, Yokoi H, Kasahara M, Imamaki H, Ishii A, Kuwabara T, Koga K, Kato Y, Toda N, Ohno S, Kuwahara K, Endo T, Nakao K, Yanagita M, Mukoyama M, Mori K. Increase of Total Nephron Albumin Filtration and Reabsorption in Diabetic Nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 28 (2017) 278–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lebeau C, Debelle FD, Arlt VM, Pozdzik A, De Prez EG, Phillips DH, Deschodt-Lanckman MM, Vanherweghem JL, Nortier JL. Early proximal tubule injury in experimental aristolochic acid nephropathy: functional and histological studies. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 20 (2005) 2321–2332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perez Bay AE, Schreiner R, Benedicto I, Paz Marzolo M, Banfelder J, Weinstein AM, Rodriguez-Boulan EJ. The fast-recycling receptor Megalin defines the apical recycling pathway of epithelial cells. Nat Commun. 7 (2016) 11550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gburek J, Verroust PJ, Willnow TE, Fyfe JC, Nowacki W, Jacobsen C, Moestrup SK, Christensen EI. Megalin and cubilin are endocytic receptors involved in renal clearance of hemoglobin. J Am Soc Nephrol. 13 (2002) 423–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pohl M, Kaminski H, Castrop H, Bader M, Himmerkus N, Bleich M, Bachmann S, Theilig F. Intrarenal renin angiotensin system revisited: role of megalin-dependent endocytosis along the proximal nephron. J Biol Chem. 285 (2010) 41935–41946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schuh CD, Polesel M, Platonova E, Haenni D, Gassama A, Tokonami N, Ghazi S, Bugarski M, Devuyst O, Ziegler U, Hall AM. Combined Structural and Functional Imaging of the Kidney Reveals Major Axial Differences in Proximal Tubule Endocytosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 29 (2018) 2696–2712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhuo JL, Li XC. Proximal nephron. Compr Physiol. 3 (2013) 1079–1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marino M, Andrews D, Brown D, McCluskey RT. Transcytosis of retinol-binding protein across renal proximal tubule cells after megalin (gp 330)-mediated endocytosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 12 (2001) 637–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.He FF, Gong Y, Li ZQ, Wu L, Jiang HJ, Su H, Zhang C Wang YM. A New Pathogenesis of Albuminuria: Role of Transcytosis. Cell Physiol Biochem. 47 (2018) 1274–1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dickson LE, Wagner MC, Sandoval RM, Molitoris BA. The proximal tubule and albuminuria: really! J Am Soc Nephrol. 25 (2014) 443–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Santoyo-Sanchez MP, Pedraza-Chaverri J, Molina-Jijon E, Arreola-Mendoza L, Rodriguez-Munoz R, Barbier OC. Impaired endocytosis in proximal tubule from subchronic exposure to cadmium involves angiotensin II type 1 and cubilin receptors. BMC Nephrol. 14 (2013) 211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kozyraki R. Cubilin a multifunctional epithelial receptor: an overview. J Mol Med (Berl). 79 (2001) 161–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Verroust PJ. Pathophysiology of cubilin: of rats, dogs and men. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 17 Suppl 9 (2002) 55–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ehlayel AM, Copelovitch L. Update on Dent Disease. Pediatr Clin North Am. 66 (2019) 169–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gabriel SS, Belge H, Gassama A, Debaix H, Luciani A, Fehr T, Devuyst O. Bone marrow transplantation improves proximal tubule dysfunction in a mouse model of Dent disease. Kidney Int. 91 (2017) 842–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Norden AG, Lapsley M, Lee PJ, Pusey CD, Scheinman SJ, Tam FW, Thakker RV, Unwin RJ, Wrong O. Glomerular protein sieving and implications for renal failure in Fanconi syndrome. Kidney Int. 60 (2001) 1885–1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roksnoer LC, Heijnen BF, Nakano D, Peti-Peterdi J, Walsh SB, Garrelds IM, van Gool JM, Zietse R, Struijker-Boudier HA, Hoorn EJ, Danser AH. On the Origin of Urinary Renin: A Translational Approach. Hypertension. 67 (2016) 927–933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Raggi C, Fujiwara K, Leal T, Jouret F, Devuyst O, Terryn S. Decreased renal accumulation of aminoglycoside reflects defective receptor-mediated endocytosis in cystic fibrosis and Dent's disease. Pflugers Arch. 462 (2011) 851–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Larsen CP, Trivin-Avillach C, Coles P, Collins AB, Merchant M, Ma H, Wilkey DW, Ambruzs JM, Messias NC, Cossey LN, Rosales IA, Wooldridge T, Walker PD, Colvin RB, Klein J, Salant DJ, Beck LH Jr., LDL Receptor-Related Protein 2 (Megalin) as a Target Antigen in Human Kidney Anti-Brush Border Antibody Disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 29 (2018) 644–653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tojo A, Onozato ML, Ha H, Kurihara H, Sakai T, Goto A, Fujita T, Endou H. Reduced albumin reabsorption in the proximal tubule of early-stage diabetic rats. Histochem Cell Biol. 116 (2001) 269–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Russo LM, del Re E, Brown D, Lin HY. Evidence for a role of transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta1 in the induction of postglomerular albuminuria in diabetic nephropathy: amelioration by soluble TGF-beta type II receptor. Diabetes. 56 (2007) 380–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ogasawara S, Hosojima M, Kaseda R, Kabasawa H, Yamamoto-Kabasawa K, Kurosawa H, Sato H, Iino N, Takeda T, Suzuki Y, Narita I, Yamagata K Tomino Y, Gejyo F, Hirayama Y, Sekine S, Saito A. Significance of urinary full length and ectodomain forms of megalin in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 35 (2012) 1112–1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.De S, Kuwahara S, Hosojima M, Ishikawa T, Kaseda R, Sarkar P, Yoshioka Y, Kabasawa H, Iida T, Goto S, Toba K, Higuchi Y, Suzuki Y Hara M, Kurosawa H, Narita I, Hirayama Y, Ochiya T, Saito A. Exocytosis-Mediated Urinary Full-Length Megalin Excretion Is Linked With the Pathogenesis of Diabetic Nephropathy. Diabetes. 66 (2017) 1391–1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saito A, Takeda T, Hama H, Oyama Y, Hosaka k, Tanuma A, Kaseda R, Ueno M, Nishi S, Ogasawara S, Gondaira F, Suzuki Y, Gejyo F. Role of megalin, a proximal tubular endocytic receptor, in the pathogenesis of diabetic and metabolic syndrome-related nephropathies: protein metabolic overload hypothesis. Nephrology (Carlton). 10 Suppl 2005. S26–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yamamoto T, Takabatake Y, Takahashi A, Kimura T, Namba T, Matsuda J, Minami S, Kaimori JY, Matsui I, Matsusaka T Niimura F, Yanagita M, Isaka Y. High-Fat Diet-Induced Lysosomal Dysfunction and Impaired Autophagic Flux Contribute to Lipotoxicity in the Kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol. 28 (2017) 1534–1551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kuwahara S, Hosojima M, Kaneko R, Aoki H, Nakano D, Sasagawa T, Kabasawa H, Kaseda R, Yasukawa R, Ishikawa T, Suzuki A, Sato H, Kageyama S, Tanaka T, Kitamura N, Narita I, Komatsu M, Nishiyama A, Saito A. Megalin-Mediated Tubuloglomerular Alterations in High-Fat Diet-Induced Kidney Disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 27 (2016) 1996–2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Motoyoshi Y, Matsusaka T, Saito A, Pastan I, Willnow TE, Mizutani S, Ichikawa I. Megalin contributes to the early injury of proximal tubule cells during nonselective proteinuria. Kidney Int. 74 (2008) 1262–1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hori Y, Aoki N, Kuwahara S, Hosojima M, Kaseda R, Goto S, Iida T, De S, Kabasawa H, Kaneko R, Aoki H, Tanabe Y, Kagamu H, Narita I, Kikuchi T, Saito A. Megalin Blockade with Cilastatin Suppresses Drug-Induced Nephrotoxicity. J Am Soc Nephrol. 28 (2017) 1783–1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weyer K, Andersen PK, Schmidt K, Mollet G, Antignac C, Birn H, Nielsen R, Christensen EI. Abolishment of proximal tubule albumin endocytosis does not affect plasma albumin during nephrotic syndrome in mice. Kidney Int. 93 (2018) 335–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Leheste JR, Rolinski B, Vorum H, Hilpert J, Nykjaer A, Jacobsen C, Aucouturier P, Moskaug JO, Otto A, Christensen EI, Willnow TE. Megalin knockout mice as an animal model of low molecular weight proteinuria. Am J Pathol. 155 (1999) 1361–1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Muller D, Ankermann T, Stephani U, Kirschstein M, Szelestei T, Luft FC, Willnow TE. Holoprosencephaly and low molecular weight proteinuria: the human homologue of murine megalin deficiency. Am J Kidney Dis. 37 (2001) 624–628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shrestha S, Sunaga H, Hanaoka H, Yamaguchi A, Kuwahara S, Umbarawan Y, Nakajima K, Machida T, Murakami M, Saito A, Tsushima Y, Kurabayashi M, Iso T. Circulating FABP4 is eliminated by the kidney via glomerular filtration followed by megalin-mediated reabsorption. Sci Rep. 8 (2018) 16451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Weyer K, Storm T, Shan J, Vainio S, Kozyraki R, Verroust PJ, Christensen EI, Nielsen R. Mouse model of proximal tubule endocytic dysfunction. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 26 (2011) 3446–3451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wu C, Xu Y, Lu H, Howatt DA, Balakrishnan A, Moorleghen JJ, Vander Kooi CW, Cassis LA, Wang JA, Daugherty A. Cys18-Cys137 disulfide bond in mouse angiotensinogen does not affect AngII-dependent functions in vivo. Hypertension. 65 (2015) 800–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lu H, Wu C, Howatt DA, Balakrishnan A, Moorleghen JJ, Chen X, Zhao M, Graham MJ, Mullick AE, Crooke RM, Feldman DL, Cassis LA, Vander Kooi CW, Daugherty A. Angiotensinogen Exerts Effects Independent of Angiotensin II. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 36 (2016) 256–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lu H, Rateri DL, Feldman DL, Charnigo RJ Jr., Fukamizu A, Ishida J, Oesterling EG, Cassis LA, Daugherty A. Renin inhibition reduces hypercholesterolemia-induced atherosclerosis in mice. J Clin Invest. 118 (2008) 984–993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen X, Howatt DA, Balakrishnan A, Moorleghen JJ, Wu C, Cassis LA, Daugherty A, Lu H. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme in Smooth Muscle Cells Promotes Atherosclerosis-Brief Report. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 36 (2016) 1085–1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Navar LG, Lewis L, Hymel A, Braam B, Mitchell KD. Tubular fluid concentrations and kidney contents of angiotensins I and II in anesthetized rats. J Am Soc Nephrol. 5 (1994) 1153–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nishiyama A, Seth DM Navar LG. Renal interstitial fluid concentrations of angiotensins I and II in anesthetized rats. Hypertension. 39 (2002) 129–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Terada Y, Tomita K, Nonoguchi H, Marumo F. PCR localization of angiotensin II receptor and angiotensinogen mRNAs in rat kidney. Kidney Int. 43 (1993) 1251–1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lavoie JL, Lake-Bruse KD, Sigmund CD. Increased blood pressure in transgenic mice expressing both human renin and angiotensinogen in the renal proximal tubule. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 286 (2004) F965–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Daugherty A, Rateri DL, Lu H, Inagami T, Cassis LA. Hypercholesterolemia stimulates angiotensin peptide synthesis and contributes to atherosclerosis through the AT1A receptor. Circulation. 110 (2004) 3849–3857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Daugherty A, Cassis L. Angiotensin II-mediated development of vascular diseases. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 14 (2004) 117–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Eto H, Miyata M, Shirasawa T, Akasaki Y, Hamada N, Nagaki A, Orihara K, Biro S, Tei C. The long-term effect of angiotensin II type 1a receptor deficiency on hypercholesterolemia-induced atherosclerosis. Hypertens Res. 31 (2008) 1631–1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lu H, Balakrishnan A, Howatt DA, Wu C, Charnigo R, Liau G, Cassis LA, Daugherty A. Comparative effects of different modes of renin angiotensin system inhibition on hypercholesterolaemia-induced atherosclerosis. Br J Pharmacol. 165 (2012) 2000–2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cassis LA, Rateri DL, Lu H, Daugherty A. Bone marrow transplantation reveals that recipient AT1a receptors are required to initiate angiotensin II-induced atherosclerosis and aneurysms. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 27 (2007) 380–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rateri DL, Moorleghen JJ, Knight V, Balakrishnan A, Howatt DA, Cassis LA, Daugherty A. Depletion of endothelial or smooth muscle cell-specific angiotensin II type 1a receptors does not influence aortic aneurysms or atherosclerosis in LDL receptor deficient mice. PLoS One. 7 (2012) e51483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Taugner R, Hackenthal E, Rix E, Nobiling R, Poulsen K. Immunocytochemistry of the renin-angiotensin system: renin, angiotensinogen, angiotensin I, angiotensin II, and converting enzyme in the kidneys of mice, rats, and tree shrews. Kidney Int Suppl. 12 (1982) S33–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Taugner R, Hackenthal E, Inagami T, Nobiling R, Poulsen K. Vascular and tubular renin in the kidneys of mice. Histochemistry. 75 (1982) 473–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Matsusaka T, Niimura F, Shimizu A, Pastan I Saito A, Kobori H, Nishiyama A, Ichikawa I. Liver angiotensinogen is the primary source of renal angiotensin II. J Am Soc Nephrol. 23 (2012) 1181–1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gonzalez-Villalobos R, Klassen RB, Alle PL, Navar LG, Hammond TG. Megalin binds and internalizes angiotensin II. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 288 (2005) F420–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Li XC, Zhuo JL. Mechanisms of AT1a receptor-mediated uptake of angiotensin II by proximal tubule cells: a novel role of the multiligand endocytic receptor megalin. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 307 (2014) F222–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Li XC, Gu V, Miguel-Qin E, Zhuo JL. Role of caveolin 1 in AT1a receptor-mediated uptake of angiotensin II in the proximal tubule of the kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 307 (2014. F949–961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Daugherty A, Tall AR Daemen M, Falk E, Fisher EA, Garcia-Cardena G, Lusis AJ, Owens Ap 3rd, Rosenfeld ME, Virmani R. Recommendation on Design, Execution, and Reporting of Animal Atherosclerosis Studies: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 37 (2017) e131–e157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Peters HP, Laarakkers CM, Pickkers P, Masereeuw R, Boerman OC, Eek A, Cornelissen EA, Swinkels DW, Wetzels JF, Tubular reabsorption and local production of urine hepcidin-25, BMC Nephrol. 14 (2013) 70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]