Abstract

Luminopsins (LMOs) are chimeric proteins consisting of a luciferase fused to an opsin that provide control of neuronal activity, allowing for less cumbersome and less invasive optogenetic manipulation. It was previously shown that both an external light source and the luciferase substrate, coelenterazine (CTZ) could modulate activity of LMO-expressing neurons, although the magnitudes of the photoresponses remained subpar. In this study, we created an enhanced iteration of the excitatory luminopsin LMO3, termed eLMO3, that has improved membrane targeting due to the insertion of a Golgi trafficking signal (TS) sequence. In cortical neurons in culture, expression of eLMO3 resulted in significant reductions in the formation of intracellular aggregates, as well as in a significant increase in total photocurrents. Furthermore, we corroborated the findings with injections of adeno-associated viral (AAV) vectors into the deep layers of the somatosensory cortex (the barrel cortex) of male mice. We observed greatly reduced numbers of intracellular puncta in eLMO3-expression cortical neurons compared to those expressing the original LMO3. Finally, we quantified CTZ-driven behavior, namely whisker-touching behavior, in male mice with LMO3 expression in the barrel cortex. After CTZ administration, mice with eLMO3 displayed significantly longer whisker responses than mice with LMO3. In summary, we have engineered the superior LMO by resolving membrane trafficking defects, and we demonstrated improved membrane targeting, greater photocurrents, and greater functional responses to stimulation with CTZ.

Keywords: Golgi apparatus, photocurrent, whiskers

Graphical Abstract

We found a way to reduce protein aggregates (arrows and arrowheads) and improve surface expression of an opto-chemogenetic probe by incorporating a membrane trafficking signal (Kir2.1 TS).

INTRODUCTION

Luminopsins (LMOs) are molecular tools that enable both chemogenetic and optogenetic control of neuronal activity. They consist of a luciferase enzyme fused to an opsin and therefore allow optogenetic activation by both external light illumination as well as by internal bioluminescence with a chemical substrate, coelenterazine (CTZ). These chimeric probes are therefore well-suited for long-term in vivo studies requiring chronic optogenetic stimulation or stimulation in multiple areas of the brain. Both excitatory (Berglund, Birkner, Augustine, & Hochgeschwender, 2013; Berglund et al., 2016) and inhibitory LMOs (Berglund et al., 2016; Tung, Gutekunst, & Gross, 2015) have been successfully utilized to modulate neuronal activity in vitro and in vivo.

LMO3 is an excitatory luminopsin that consists of a light-sensitive cation channel (Volvox channelrhodopsin 1, VChR1) coupled to a variant of a bioluminescent enzyme (slow-burn Gaussia luciferase, sbGLuc). This optogenetic probe therefore allows multi-modal control of membrane potential with either external blue/green light illumination or by CTZ-derived bioluminescence. The degree of opsin activation by either direct external light illumination or chemically derived bioluminescence has been previously demonstrated to be sufficient for excitation of neurons in vitro and in vivo (Berglund et al., 2016). However, long-term expression of LMO3 has been associated with globular accumulations of the protein inside the cells (unpublished observations), similar to other unmodified optogenetic probes that form blebs in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) due to poor membrane trafficking (Gradinaru, Thompson, & Deisseroth, 2008; S. Zhao et al., 2008). This poses a concern for long-term cellular health, as well as limited photocurrent responses resulting from suboptimal membrane expression.

In this study, we sought to improve membrane trafficking of LMO3 using cellular trafficking methods previously utilized by Gradinaru et al. (2010) and Yizhar et al. (2011). Specifically, the Golgi export trafficking signal (TS) from a neuronal potassium channel (Kir2.1)(Hofherr, Fakler, & Klöcker, 2005) was added to the LMO3 fusion protein to create an enhanced LMO3 (eLMO3). We tested whether decreased ER accumulations and improved membrane trafficking of LMO3 would result in more robust excitation of neuronal activity and indeed found that eLMO3 produced greater photoresponses in vitro and in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All the procedures involving live mice described in this article were approved prior to implementation of the procedures and conducted in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees (IACUC) of Emory University.

In this study, we utilized 3 new DNA plasmids derived from two plasmids that had been published before (Berglund et al., 2016), as summarized below (Table 1).

Table 1.

A list of DNA plasmids used in this study.

| Construct | Motifs | Experiments | Figures |

|---|---|---|---|

| pCAG-LMO3 | From [2] | In vitro electrophysiology, bioluminescence assay | 1 |

| pCAG-eLMO3 | KSRITSEGEYIPLDQIDINV between VChR1 and EYFP | Intermediate plasmid to obtain the AAV vector below | None |

| pCAG-LMO3ΔSS | Deletion of the first 16 AA (GVKVLFALICIAVAEA) in sbGLuc | In vitro electrophysiology | 1 |

| pAAV-LMO3 | From [2] | In vitro expression and electrophysiology, in vivo expression, behavior | 2,3,4 |

| pAAV-eLMO3 | eLMO3 in an AAV vector | In vitro expression and electrophysiology, in vivo expression, behavior | 2,3,4 |

EYFP: enhanced yellow fluorescent protein; AA: amino acids; AAV: adeno-associated virus

Subcloning

DNA plasmids were made using conventional molecular biological techniques. The correct sequences were confirmed by digestion with restriction enzymes (RE) and DNA sequencing.

To insert the Kir2.1 TS in LMO3, the TS-EYFP cassette within pAAV-CaMKIIα-SwiChRCA-TS-EYFP (Addgene plasmid #: 55630; a gift from Karl Deisseroth, Stanford University) (Berndt, Lee, Ramakrishnan, & Deisseroth, 2014) was cut with RE, NotI and BsrGI, agarose gel-purified, and then ligated into pCAG-LMO3 using the respective RE sites, resulting in a mammalian expression vector with enhanced LMO3 under control of the CAG promoter (pCAG-eLMO3). To obtain an AAV vector with eLMO3, the whole eLMO3 cassette in pCAG-eLMO3 was cut using BglII and BsrGI and then ligated into compatible RE sites (BamHI and BsrGI) of pAAV-LMO3 [2], resulting in an AAV vector with eLMO3 under control of the human synapsin I promoter (pAAV-eLMO3).

GLuc is a secreted protein. To delete the secretion signal (AA2-17) in sbGLuc in LMO3, the sbGLuc cassette without the secretion signal in pCAG-sbGLucΔSS-tdTomato (a gift from Ute Hochgeschwender) was PCR-amplified with the primers containing the HindIII and BamHI RE sites (HindIII forward: ataaagcttgccaccatgaagcccaccgagaacaacgaag; BamHI reverse: aatggatccccgtcaccaccggccccctt), digested with the enzymes, and ligated into pCAG-LMO3 using the respective RE sites, resulting in a mammalian expression vector with LMO3 without the secretion signal under control of the CAG promoter (pCAG-LMO3ΔSS).

Viral vector

AAV vectors pseudotyped with recombinant AAV2/9 were made from pAAV-LMO3 and pAAV-eLMO3 through the Emory Viral Vector Core, with both of the titers determined by qPCR to be 1.8×1013 viral genomes (vg)/ml. AAV vectors were resuspended in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

Primary neuronal culture

Primary neuronal culture was made using the neocortex dissected from the mouse embryonic brains of mixed sexes (embryonic day: E14–16; strain: C57BL6/J; litter size: 6 – 10) as previously described (Ogle, Gu, Espinera, & Wei, 2012). We used 3 litters in this study. Cells were seeded onto poly-D-lysine coated 18-mm coverslips (neuVitro, Vancouver, WA, USA) in 12-well plates or 96-well plates (Corning, Corning, NY, USA) and were initially maintained in Neurobasal medium (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) with GlutaMAX (Life Technologies), heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (5% v/v), and gentamicin (final concentration: 1 μg/ml; Life Technologies). One day after seeding, culture medium was fully changed with serum/antibiotics-free Neurobasal with B-27 serum-free culture supplement (Life Technologies), followed by half-volume medium changes every 7 day. For plate reader assays in 96-well plates, same culture medium, but without phenol red, was used.

The transgenes were delivered to the cultured cells by either electroporation or AAV infection. Electroporation was done with the 4D-Nucleofector System (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) following the manufacturer’s instructions with minor modifications. For each reaction, immediately after dissociation, ~6 million cells were spun down at 100 relative centrifugal force for 10 minutes, resuspended in 100 μl of Dulbecco’s PBS (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) supplemented with 3 μg of a DNA plasmid (1 μg/μl in Tris-EDTA buffer, Life Technologies), transferred to a cuvette and then electroporated using either the program CU-133 (with high viability for patch clamp experiments) or EM-110 (with high expression levels for bioluminescent assays). The cells were added with 500 μl of pre-equilibrated RPMI 1640 Medium (Life Technologies) and placed in a CO2 incubator for ~5 minutes. After this recovery step, the cells were plated at the density of 1.5×106 cells/well (12-well plate for patch clamping) or 4×104 cells/well (96-well plate for bioluminescent assays).

Alternatively, neurons were infected with an AAV vector 1 day in vitro (DIV). This was done by adding 100 nl of AAV suspension per ml of culture medium at the time of full medium change. This corresponds to multiplicity of infection of ~103.

Fluorescence microscopy and electrophysiology

At DIV14, the coverslips containing cortical neurons were imaged by an inverted epifluorescent microscope (Leica DM-IRB, Leica, Weitzlar, Germany or Olympus IX53, Waltham, MA, USA) equipped with a CCD or an sCMOS camera (OptiMOS, QImaging, Surrey, BC, Canada), respectively, and a mercury lamp. Fluorescent images were taken with 10x, 20x, or 40x fluorescence objective lens with an FITC filter cube (41001, Chroma, Bellows Falls, VT, USA). Bright field images were also acquired with phase contrast.

Whole-cell patch clamp recording was performed using the Olympus IX53 inverted microscope equipped with a micromanipulator (Sutter Instrument, Novato, CA, USA). The membrane currents or potentials were collected using an EPC9 amplifier and Pulse software (HEKA Elektronik, Lambrecht, Germany) at room temperature (~22°C). The external solution contained 150 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2, 10 mM HEPES, and 20 mM glucose at a pH of 7.35. The internal solution consisted of 140 mM K-gluconate, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM CaCl2, 4 mM Na2-ATP, 0.4 mM Na3-GTP, 5 mM EGTA, and 10 mM HEPES at a pH of 7.15. Recording electrodes pulled from borosilicate glass pipettes (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL, USA) had a tip resistance between 5 and 7 MΩ when filled with the internal solution. Series resistance was compensated by up to 50%. Data was filtered at 3 kHz and digitized at sampling rates of 10 kHz. Widefield photostimulation was delivered through an oil-immersion objective lens (40x; 1.35NA; UApo/340, Olympus) using a bandpass excitation filter (460–500 nm) in the FITC filter cube. Intensity was adjusted by ND filters (ND25 and ND6, Olympus). CTZ stock solution (50 mM in Fuel Solvent, #303, Nanolight, Pinetop, AZ, USA) was diluted in 500 μl of the extracellular solution at concentration of 100 μM and bath-applied to the recording chamber which already contained ~500 μl of the extracellular solution (final concentration of CTZ: ~50 μM).

Bioluminescence measurements

Bioluminescence was measured between DIV10 and DIV14 using a plate reader (FLUOstar Optima, BMG Labtech, Ortenberg, Germany) immediately after adding CTZ to each well (final concentration 33 μM in culture medium). To correct for the background, CTZ was added to wells with neurons without transfection and the averaged signal was subtracted.

Stereotactic AAV injections

Stereotactic injections into the barrel cortex of male mice was performed according to previously established protocols (Berglund et al., 2016). Anesthesia in mice was induced by 3.5% isoflurane in oxygen and maintained by 1.5% isoflurane, during which the mice were placed in a stereotactic apparatus (David Kopf Instruments). For injection of viruses, a 33-gauge syringe needle in a Nanofil syringe (World Precision Instruments) was used to infuse 2 μl of virus suspension into the deep layers of the barrel cortex (coordinates from the bregma: −1 mm AP, +3.5 mm ML; depth from the dura: 0.5 mm) at a rate of 100 nl/min. The needle was left in place for 10 min after injection before being slowly withdrawn. The incision was closed with tissue adhesive (3M Vetbond, Maplewood, MN, USA). After surgery, mice were given daily doses of meloxicam (1 mg/kg body weight) for analgesia until they fully recovered from surgery.

Antibody characterization

In this study, the following antibodies were used (Table 2).

Table 2.

A list of antibodies used in this study.

| Name | Immunogen | Catalog number | Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-GFP | Full length (246AA) recombinant A. victoria GFP | Novus Biologicals 100–1770, goat polyclonal | 5.5 μg/ml |

| Anti-goat IgG conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 | Goat IgG heavy and light chains | Abcam 150129, donkey polyclonal | 10 μg/ml |

The manufacture validated specificity in Western blot. Anti-GFP antibody recognized A. victoria GFP in a single band at a predicted size of 28 kDa. In our immunohistochemical analysis, the staining pattern was similar to that of innate fluorescence from the EYFP tag of luminopsin without immunostaining.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed as described before (Y. Zhao et al., 2017). Mice were euthanized by CO2 overdose 35 days after AAV injection. After euthanasia, cardiac perfusion was performed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS and coronal sections were cut at 15 μm thickness with a cryostat. For immunostaining, sections were dried for 30 min and then fixed with 10% buffered formalin for 10 min, followed by a second fixation in ethanol:acetic acid (2:1) at −20°C for 10 min. Then, the sections were permeabilized with 0.2% Triton-X 100 in PBS for 5 min. Sections were washed 3 times with PBS after each step. Then, sections were blocked with 1% fish gelatin (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS for 1 hour at room temperature, and subsequently incubated with the primary antibody (anti-GFP) overnight at 4°C to stain for the EYFP tag in luminopsins. The following day, sections were washed 3 times with PBS and then incubated with the secondary antibody (anti-goat IgG conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488) for 1 hour at room temperature. After 3 washes with PBS, the sections were mounted with antifade mounting medium (Vectashield with DAPI, Vector Laboratory, Burlingame, CA, USA), and covered with glass coverslips for fluorescence microscopy described above using the 40x objective lens. Cell counting was performed stereologically as described previously (Wei et al., 2013). For each mouse, six 15 μm-thick sections spanning the entire region of interest were randomly selected for counting, and each of them was at least 100 μm apart from the next. Counting was performed on six randomly selected non-overlapping fields per section located in the injection regions. Between mice, sections from the same anterior-posterior coordinates were analyzed.

Behavior

Whisker touching behavior was recorded and analyzed using the HomeCageScan system (Clever Sys Inc, Reston, VA, USA)(Yu et al., 2019). The system had four cameras that simultaneously monitored and recorded four cages, with each cage (dimension: 191 mm × 292 mm × 127 mm) containing one mouse. This system has been extensively calibrated and validated to provide accurate and automated and reliable behavioral output analyses (e.g. Lee et al., 2014). Male mice received viral injections for either LMO3 or eLMO3 expression in the barrel cortex as described above. We used 2 animals per group. Mice were injected with either water-soluble isotonic CTZ (30 μl of 2.5 μg/μl (6 mM) solution dissolved in sterile water, Nanolight, Pinetop, AZ, USA) or equal volumes of saline (sterile 0.9% w/v NaCl solution) via the intranasal route according to previously established protocols (Sun et al., 2015; Yu et al., 2019). The dosage of CTZ translates to 3 mg/kg or about 90 μM at the plasma level when evenly distributed for an estimated total blood volume of 1.9–2.0 ml in a 25-g mouse (Harkness & Wagner, 1989; Mitruka & Rawnsley, 1981). After the final injection of CTZ, the animals were placed into the individual cages and allowed to acclimate for 5 minutes before simultaneous behavior recording and analysis for a total of 1 hour. The settings for the data acquisition system were set as the following: (1) animal size threshold (pixel)=160; (2) contrast threshold=23. The whisker response behavior was defined as the total grooming behavior automatically detected by the system, and the duration was summed over every 5 minutes for the whole 1-hour episode.

Statistical analysis

Student’s t-tests for two conditions and Tukey’s pairwise comparisons following ANOVA for more than two conditions were carried out using Igor Pro 8 (WaveMetrics; Lake Oswego, OR, USA) or Prism 8 (GraphPad; San Diego, CA, USA). All the tests were two-tailed, and the significance level was set at 0.05. Number of samples, statistics and actual p values, when significant, were reported in the text. For electrophysiological data, we excluded recordings when the leak current became more than 100 pA when voltage-clamped at −60 mV. For plate-reader assays, we excluded wells when the readings became negative after background subtraction. The histological data was analyzed by a person who was blind to experimental conditions. The behavioral data analysis was automated for unbiased quantification. Mice from the same litter was assigned to different experimental conditions (i.e. naïve, LMO3, or eLMO3 virus injections). The order of drug administrations (CTZ vs. saline control) was counterbalanced among mice.

RESULTS

Secretion signal in LMO3 is necessary for membrane targeting

Volvox channelrhodopsin 1 (VChR1) has superior sensitivity to light compared to Chlamydomonas channelrhodopsin 2, making it an ideal actuator for bioluminescent activation (Berglund et al., 2013). However, its poor photocurrent and membrane trafficking tends to result in insufficient depolarization for firing in neurons (Lin, 2011; Tsunoda & Hegemann, 2009). Inconsistent with these previous studies, VChR1 fusion protein, LMO3, showed a large photocurrent as well as robust firing upon conventional photostimulation (Berglund et al., 2013). In LMO3, mutated Gaussia luciferase (sbGLuc), which is a secreted protein, is anchored to the membrane by fusing it with a membrane protein, VChR1. The fusion protein also contains a fluorescent tag, the enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (EYFP). The design of LMO3 may be improving membrane targeting and expression of VChR1 as the sbGLuc moiety is expected to be secreted from a cell through its secretion signal (SS; Fig. 1a, top).

Figure 1. Removal of the secretion signal diminished membrane targeting and photocurrents.

a. Linear maps of the original LMO3 cassette (top) and the LMO3 cassette without the secretion signal (SS) in sbGLuc (LMO3ΔSS; bottom) in the plasmid backbone. b. Representative bright-field and epi-fluorescent images of cortical neurons transfected with either LMO3 or LMO3ΔSS. Note the cells in the center were patch-clamped with glass pipettes. Fluorescence in the LMO3ΔSS condition was very dim but was distinguishable from autofluorescence in presumably non-transfected cells. The scale bar in the top left panel applies to the rest of the panels. c. Representative current traces in response to photostimulation with an arc-lamp (460–500 nm light; 300 μW/mm2 for 1 s; cyan bar). LMO3-expressing or LMO3ΔSS-expressing cortical neuron was whole-cell patch clamped and held at −60 mV. d. Mean photocurrents to conventional photostimulation. As a control, recordings were made from cells transfected with VChR1 alone without sbGLuc as well. n = 8, 9, 8 cells for LMO3, LMO3ΔSS, and VChR1, respectively. **p < 0.007 (Tukey’s pairwise comparisons following one-way ANOVA; q(3,22) > 4.68; F(2,22) = 7.66). e. Mean bioluminescence in response to 33-μM CTZ measured by a plate reader. n = 8 wells each. ***p = 0.00002 (two-tailed Student’s t-test; t(7) = 10.12). Error bars in this and subsequent figures denote the standard errors of the mean.

To test this hypothesis, we removed the SS from LMO3 (LMO3ΔSS; Fig. 1a, bottom) and compared its protein expression with that of the original LMO3 with the SS. Dissociated mouse cortical neurons in culture were transfected with either construct through electroporation, and membrane expression was assessed as fluorescence from EYFP under a fluorescence microscope, photocurrent through VChR1 under voltage-clamp patch clamp, and bioluminescence from sbGLuc using a plate reader. LMO3ΔSS resulted in virtually no membrane expression based on fluorescence (Fig. 1b), photocurrent (Figs. 1c and 1d), and bioluminescence (Fig. 1e), confirming the pivotal role of the SS in the fusion protein. Although, on average, we observed larger photocurrents with LMO3 than with VChR1 itself (Fig. 1d), the difference was not statistically significant (one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s pairwise comparisons; q(3,22) = 0.12; p > 0.99; **p = 0.003; F(2, 22) = 7.66; n = 8, 9, 8 for LMO3, LMO3ΔSS, and VChR1, respectively). Photocurrent with LMO3ΔSS was significantly smaller than the other two conditions (q(3,22) = 4.81 and 4.68; **p = 0.007 and 0.009). Bioluminescence from neurons expressing LMO3ΔSS was significantly smaller than those expressing LMO3 (two-tailed Student’s t-test; t(7) = 10.12; ***p = 0.00002; n = 8 each; Fig. 1e). Thus, the SS did not improve membrane trafficking of VChR1 significantly, although it was vital for proper membrane expression of LMO3.

Enhanced photocurrent and improved membrane localization of LMO3 with the membrane trafficking signal in cultured neurons in vitro

Previous studies on optogenetic probes have shown that the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and Golgi export motifs in the Kir2.1 sequence improves trafficking of the foreign membrane proteins from the ER to the cell membrane (Gong, Li, & Schnitzer, 2013; Gradinaru et al., 2010; Hofherr et al., 2005). To improve membrane targeting, we inserted the Golgi export trafficking signal (TS) from Kir2.1 into the original LMO3 backbone to create the enhanced LMO3 (eLMO3) in a mammalian expression plasmid (Fig. 2a). The eLMO3 cassette was then subcloned into an adeno-associated viral (AAV) vector with the human synapsin I promoter for neuronal specificity and viral vectors pseudotyped with recombinant AAV2/9 was produced. Then, we infected primary culture of cortical neurons with either the original LMO3 AAV or the eLMO3 AAV one day after seeding by adding the same volume of virus suspension to the culture medium. Viral titers were approximately equal (1.8 × 1013 vg/ml for both LMO3 and eLMO3), and we assumed that the multiplicity of infection was very similar between the two conditions. We first characterized the distribution of both transgene products in neurons 15–16 days in vitro (DIV). LMO3 was seen in multiple neuronal compartments, including the putative ER in the soma (Fig. 2b, top right, arrows), but more so within the neurite branching points typically enriched with the ER (Fig. 2b, top right, arrowheads). The addition of the TS nearly completely abolished the presence of protein aggregates, and fluorescence from the EYFP tag of eLMO3 was predominantly observed around the soma and in neurites (Fig. 2b, bottom right), consistent with proper membrane targeting of the protein.

Figure 2. Insertion of the trafficking signal improved membrane targeting and photocurrents.

a. Linear maps of the original LMO3 cassette (top) and the eLMO3 cassette with the Kir2.1 trafficking signal (TS) insertion (bottom) in the plasmid backbone. b. Representative bright-field and epi-fluorescent images of cortical neurons infected with either LMO3 or eLMO3 at low (left) or high magnification (right). Note the distribution of high-intensity EYFP blebs across multiple neuronal compartments, including the soma (arrows) and neurites (arrowheads) with LMO3. c. Representative current traces in response to photostimulation with an arc-lamp (460–500 nm light; 300 μW/mm2 for 1 s; cyan bar). LMO3-expressing or eLMO3-expressing cortical neuron was whole-cell patch clamped and held at −60 mV. d. Mean photocurrents by conventional photostimulation. n = 10 and 12 cells for LMO3 and eLMO3, respectively. *p = 0.042 (two-tailed Student’s t-test; t(19) = 19.04). e. Mean bioluminescence in response to 33-μM CTZ measured by a plate reader. n = 15 and 14 wells for LMO3 and eLMO3, respectively. *p = 0.040 (two-tailed Student’s t-test; t(18) = 2.21). f. Representative bioluminescence (top) and current traces (bottom) in response to bath-applied CTZ (100 μM; arrow). The inset shows a bioluminescent image under the microscope. The recordings were obtained from the same eLMO3-expressing cell shown in c. g. Mean CTZ-induced photocurrents. 100-μM CTZ was bath-applied. n = 7 and 6 cells for LMO3 and eLMO3, respectively. *p = 0.048 (two-tailed Student’s t-test; t(11) = 2.23). h. Mean coupling efficiency (CTZ-induced currents divided by lamp-induced current). n = 7 and 6 cells for LMO3 and eLMO3, respectively. p > 0.88 (two-tailed Student’s t-test; t(11) = 0.15).

Next, we assessed whether the improved membrane targeting also enhanced the function of the luminopsin. For the comparison, either LMO3- or eLMO3-expressing neurons were patch-clamped. We first measured the photocurrent to saturating photostimulation with an arc lamp (300 μW/mm2; 460–500 nm). Photocurrent with LMO3 was larger than in the experiments in the previous section, probably due to differences in modes of transfection (electroporation vs. viral infection) and promoters (CAG vs. hSynI). We observed a nearly 2-fold increase in the photocurrent of eLMO3 over that of LMO3 (Fig. 2c). The increase was statistically significant (two-tailed Student’s t-test; *p = 0.042; t(19) = 19.04; n = 10 and 12 for LMO3 and eLMO3, respectively; Fig. 2d). Similarly, when bioluminescence from sbGLuc was evaluated with a plate reader, we found that eLMO3-expressing cortical neurons emitted approximately 2-fold greater luminescence as compared to LMO3-expressing cortical neurons when coelenterazine (CTZ; final concentration: 33 μM), the substrate for luminopsins, was applied (two-tailed Student’s t-test; *p = 0.040; t(18) = 2.21; n = 15 for LMO3 and 14 for eLMO3; Fig. 2e), consistent with improved surface expression of the membrane protein. We speculate that intracellular aggregates of LMO3 did not contribute to bioluminescence as much as membrane-expressed LMO3 due to the following reasons. In the configuration of LMO3, sbGLuc is attached to the N-terminus of VChR1, which is facing outside of the cell and CTZ is more accessible to luminopsins on the cell membrane when applied from the outside. In fact, it is known that placing GLuc outside the cell surface by placing it in the extracellular domain of a membrane-anchored protein, CD8, greatly enhances the bioluminescent signal (Santos et al., 2009). In addition, an active extrusion mechanism of CTZ through the multidrug resistance MDR1 P-glycoprotein (Pichler, Prior, & Piwnica-Worms, 2004) can contribute to greater availability of CTZ outside the cell.

Next, we applied CTZ (100 μM) to the bath solution while conducting a whole-cell patch-clamp recording from an eLMO3-expressing cell, which resulted in bioluminescence and bioluminescence-mediated photocurrent (Fig. 2f). Similar to the responses to physical light, eLMO3 resulted in a significantly larger photocurrent (about 2-fold on average) than that of LMO3 (two-tailed Student’s t-test; *p = 0.048; t(11) = 2.23; n = 7 and 6 cells for LMO3 and eLMO3, respectively; Fig. 2g). We also calculated the coupling efficiency, which is defined as the photocurrent induced by a saturating concentration of CTZ (100 μM) divided by that evoked by a saturating intensity of lamp (300 μW/mm2) (Berglund et al., 2016). The coupling efficiency was similar between the two versions of luminopsins and was not significantly different (two-tailed Student’s t-test; p > 0.8; t(11) = 0.152; n = 7 and 6 cells for LMO3 and eLMO3, respectively; Fig. 2h).

These experiments indicate that surface expression of LMO3 was significantly enhanced by adding the TS in eLMO3. The TS did not affect efficiency of the channel to be activated by bioluminescence, as proportions of the channels activated by bioluminescence was similar between the two versions of luminopsins (~6%). Therefore, the improved surface expression in the eLMO3 group resulted in larger CTZ-induced responses.

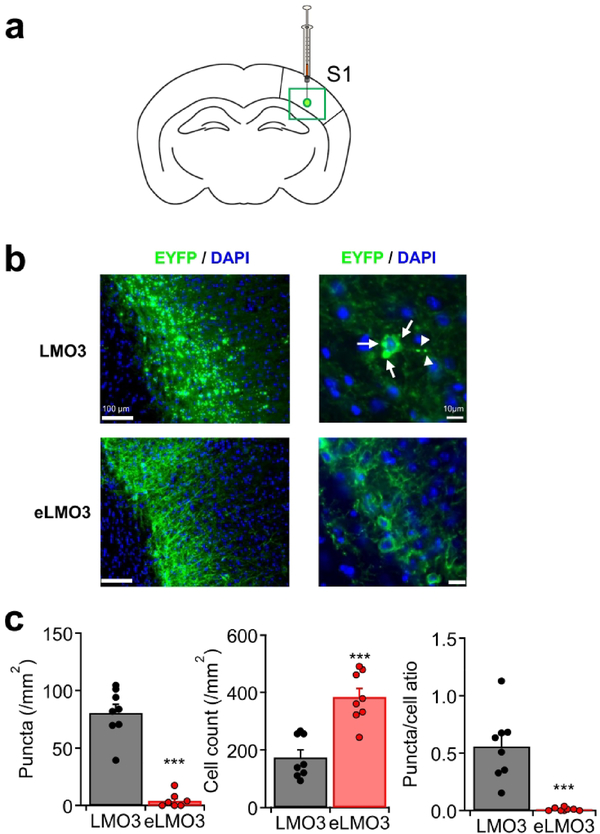

Improved membrane trafficking of LMO3 in the mouse brain

To confirm the efficacy of the TS in an in vivo setting, we injected the AAV vector, either with LMO3 or eLMO3, into the mouse primary somatosensory cortex (S1) and quantified membrane targeting of LMO3 through immunohistochemistry (Fig. 3a). Histological sections were prepared 35 days after injections and the fluorescence signal was amplified by immunostaining against the EYFP tag of LMO3 and the distribution of the expressed protein was evaluated within the injection sites (Fig. 3a, green box). Fluorescence was primarily observed in pyramidal cells of the deep cortical layers. Sections were location-matched and counting of protein aggregates was performed only of deeper-layer neurons around the epicenter of the AAV injection. Similar to what was observed in vitro, aggregates of LMO3 were observed in both the cell body and neurites (Fig. 3b, top right, arrows and arrowheads, respectively). These dense puncta were not observed in neurons expressing eLMO3 (Fig. 3b, bottom right). We quantified the total numbers of puncta and EYFP-positive somata, as well as the ratio of puncta to cell bodies in each microscopic field. The Kir2.1 TS in eLMO3 resulted in greatly improved membrane targeting of the fusion protein, which manifested as significantly decreased numbers of total puncta and more pronounced somatic expression of luminopsin (Fig. 3c) (two-tailed Student’s t-test; ***p < 0.0001; t(14) = 9.863, 5.215, and 5.351; n = 8 images for both the LMO3 and eLMO3 groups; for the numbers of puncta, the numbers of cells, and puncta-to-somata ratio, respectively). Thus, addition of the TS significantly reduced protein aggregates and improved surface expression of eLMO3 in vivo after virus-mediated chronic expression, similar to dissociated neurons in culture.

Figure 3. Cortical expression of eLMO3 in mice displayed enhanced membrane trafficking without obvious formation of aggregates.

a. Diagram depicting the injection site of the AAV in the primary somatosensory cortex (S1). The green box denotes region of interest (ROI) for image analysis. b. Representative immunohistochemical images. Prolific aggregate formation within the injected region was observed with LMO3 whereas obvious aggregates were not observed with eLMO3. Upon higher magnification, blebs could be observed in both the cell bodies (arrows) and neurites (arrowheads) in animals with LMO3 AAV injections. Nuclei were labeled with DAPI. c. Mean total numbers of puncta (left), total numbers of EYFP-positive cells (center), and puncta-to-cell ratio (right). n = 8 sections each. ***p < 0.0001 in two-tailed Student’s t-test.

Improved targeting of LMO3 elicits greater behavioral responses

AAV injection into the S1, specifically the barrel cortex (BC), allowed for examination of behavioral effects of the CTZ-induced activity of transduced cortical neurons. The BC is the tertiary structure in the whisker thalamocortical pathway, for which sensory signals from the whisker ascend the barrelettes of the brainstem to the ventroposteromedial (VPM) nucleus of the thalamus, and finally to the deep layers of the BC (Fig. 4a). Thus, by stimulating the target neurons in the BC, we expected to induce an artificial sensation of repetitive whisker deflections, which would produce a slight irritation for the mouse and evoke a continuous whisker brushing or grooming-like behavior, which we defined as “whisker response” (Yu et al., 2019)(Fig. 4b). To test this hypothesis, we injected CTZ (30 μl of 6 mM in saline) via intranasal delivery and quantified the duration of whisker response through an automated behavior observation system. Intranasal injections are a well-established route for delivering blood-brain barrier-permeable agents, such as CTZ, directly into the brain, and they provide more bioavailability of the injected agent in the neocortex than intraperitoneal injections (Chauhan & Chauhan, 2015; Hanson & Frey, 2008; Sun et al., 2015; Yu et al., 2019). Furthermore, it is less invasive and allows for convenience of access as well as ability of behavioral observation with minimal disturbance. After recovery of AAV injection with LMO3 or eLMO3, half of the mice were intranasally injected with CTZ and then was monitored for 1 hour. The other half received saline injection as a control. The experiments were repeated the following day with the experimental groups switched, such that animals that received saline the prior day would then receive CTZ, and vice versa. Then, after allowing the mice to wait for a week, the trials for both CTZ and saline injections were repeated. In this fashion, each animal was tested in 4 to 6 trials in total and 2 mice were used for each AAV treatment (LMO3 or eLMO3). We observed more whisker response up to 1 hour after CTZ injection compared to saline injection with both luminopsins, with more pronounced effects during later time points for LMO3 whereas eLMO3 showed robust responses up to 45 minutes after CTZ injection (Fig. 4c). For quantitative comparisons, total duration of whisker response was calculated and compared among the conditions including naïve animals that did not receive virus injections. We observed longer whisker responses in animals with both LMO3 and eLMO3 after CTZ administration compared to the saline controls, corroborating the stimulatory effect of CTZ (Fig. 4d). We observed a statistically significant increase of whisker responses with CTZ in both groups of mice, LMO3 and eLMO3 (two-way ANOVA; the main effect of CTZ; ***p < 0.0001; F(1,16) = 73.14), indicating that CTZ-induced neuronal activity in the BC elicited the whisker touching behavior. Indeed, the effect of CTZ was specific to luminopsins, as whisker responses elicited by CTZ in naïve animals were similar to those in control trials using saline injection in animals with LMO3 and eLMO3. Interestingly, in trials with CTZ, when eLMO3 animals were compared with LMO3 animals, the former group showed a significantly longer duration of whisker responses (Tukey’s pairwise comparison; *p = 0.0132; q(16) = 4.997), suggesting prolonged and elevated neuronal activity in the BC of the eLMO3 group after CTZ injection. The more robust response in mouse behavior was consistent with improved membrane-localized expression of LMO3.

Figure 4. Enhanced whisker response after intranasal CTZ administration in eLMO3-transduced mice.

a. The whisker thalamocortical pathway initiates with whisker deflection (arrows) in the vibrissal mechanoreceptors, which ascends to the brainstem (BS), and then the ventroposteromedial (VPM) nucleus of the thalamus (T), and finally to the barrels of the barrel cortex (BC). b. Representative screen captures of the mouse during normal exploratory behavior (left) and the whisker response (grooming of whiskers using forepaws; right). c. Time courses of whisker response following intranasal administration. The animals had received virus injection into the BC with either LMO3 (left) or eLMO3 (right) and then underwent intranasal delivery of CTZ and saline control. d. Mean duration of whisker response as measured and analyzed using the automated Home Cage Monitoring System. n = 4–6 trials. *p < 0.05 (Tukey’s pairwise comparisons following two-way ANOVA).

DISCUSSION

The LMO3 fusion protein was previously developed and characterized, and responsiveness to CTZ was demonstrated both in vitro and in vivo (Berglund et al., 2013; Berglund et al., 2016). However, we noted the persistence of LMO3 aggregates in ER-rich regions of infected cells, which we believed to impair the efficiency of photostimulation. In this study, we improved membrane targeting of LMO3 by adding the Golgi TS sequence and created a superior version, eLMO3. Transduction of eLMO3 resulted in greater photocurrents with either CTZ or external light stimulation (Fig. 2) as well as in improved membrane targeting in neurons in the BC in vivo compared to LMO3 (Fig. 3). As a test case, we quantified behavioral responses upon CTZ-derived stimulation, namely whisker touching behavior driven by activation of the BC, and observed more robust responses compared to LMO3 (Fig. 4). This observation was in line with our recent publication where LMO3-expressing neuroprogenitor cells were transplanted into the BC as a combined cell-gene therapy for a stroke model in mice (Yu et al., 2019). Thus, in addition to circling behavior driven by unilateral activation of the nigrostriatal pathway (Berglund et al., 2016; Tung et al., 2015), LMO3 has now been shown to elicit circuit-specific behaviors less invasively and more conveniently.

The increased membrane targeting of eLMO3 means that less light or CTZ is required to achieve the same levels of neuronal activation. A given cell expressing eLMO3 therefore requires less light than a cell expressing LMO3 molecules to reach the same level of effect, therefore mitigating potential heat-induced injury of tissue and potentially allowing for more non-invasive methods of light delivery (e.g. transdermal or transcranial). The same applies for chemogenetic activation of LMO3 with CTZ substrate as the same dosage of CTZ has a greater effect with eLMO3, which is advantageous in chronic long-term in vivo studies.

In this study, we also noticed that levels of membrane expression varied depending on the method of transduction when they were assessed as photocurrent (Figs. 1 and 2). Viral-mediated transduction of LMO3 resulted in greater photocurrents than electroporation of the same transgene, possibly due to the higher copy numbers of the transgene, higher promoter activity, and better integrity and overall health of neurons after transfection. Thus, the benefit of eLMO3, namely a higher degree of membrane expression, is best complemented by virus-mediated transduction.

Multiple prior studies have explored the creation of superior optogenetic tools that have improved trafficking properties, including using ER export sequences (S. Zhao et al., 2008), the Golgi export TS sequence (Gradinaru et al., 2010), or the combination of the two (Gong et al., 2013; S. Zhao et al., 2008). Although the Golgi TS sequence improved membrane trafficking only modestly when incorporated into VChR1 by itself (Yizhar et al., 2011), in this study, we were able to significantly improve membrane trafficking of the LMO3 fusion protein by including the same motif. Despite no evidence of aggregations of eLMO3 in the ER by fluorescence microscopy, there may still be aggregations present below levels of detection, and membrane trafficking could therefore be potentially further improved by utilizing ER export motifs as previously described. Other genetic modifications may also be investigated, such as a combinatorial approach with other transport/trafficking motifs, or even altering the insertion site for the motifs, which has been shown to affect the functionality of the motifs (Hofherr et al., 2005; Simon & Blobel, 1993) (Gradinaru et al., 2010).

Since the bioluminescence-induced photocurrents of eLMO3 were unable to reach saturating levels (i.e. below photocurrents induced by lamp illumination), the substrate induced photocurrents could be potentially further improved with the use of brighter luciferase enzymes. Indeed, a new line of luciferases has been developed from a brighter luciferase, NanoLuc (Promega, Madison, MI, USA) (Suzuki et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2016), and they have the appropriate emission spectrum to be paired with VChR1.

We hope that the current study and future engineering of luminopsin will further increase the utility of the molecular probe in both conventional optogenetic paradigms as well as in chemogenetic activation.

Significance statement.

The eLMO3 variant engineered in this study provides a superior probe for biological activation of neurons or other excitable cells for functional interrogation or therapeutic purposes.

OTHER ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Julie Chen and Thomas F. F. Shiu for technical assistance, Yuan Chang for drawing diagrams, and Ute Hochgeschwender for providing a plasmid.

Grant information: This work was supported by NIH grants NS062097 (LW), NS085568 (LW/SPY/REG), NS091585 (LW), NS079268 (REG), NS079757 (REG), NS086433 (JKT), NSF CBET-1512826 (KB/REG), and the Mirowski Family Foundation (REG).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

REFERENCES

- Berglund K, Birkner E, Augustine GJ, & Hochgeschwender U (2013). Light-Emitting Channelrhodopsins for Combined Optogenetic and Chemical-Genetic Control of Neurons. PLoS ONE, 8, e59759. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berglund K, Clissold K, Li HE, Wen L, Park SY, Gleixner J, . . . Rossi MA (2016). Luminopsins integrate opto-and chemogenetics by using physical and biological light sources for opsin activation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(3), E358–E367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berndt A, Lee SY, Ramakrishnan C, & Deisseroth K (2014). Structure-guided transformation of channelrhodopsin into a light-activated chloride channel. Science, 344(6182), 420–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan MB, & Chauhan NB (2015). Brain Uptake of Neurotherapeutics after Intranasal versus Intraperitoneal Delivery in Mice. Journal of neurology and neurosurgery, 2(1). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Y, Li JZ, & Schnitzer MJ (2013). Enhanced archaerhodopsin fluorescent protein voltage indicators. PLoS One, 8(6), e66959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gradinaru V, Thompson KR, & Deisseroth K (2008). eNpHR: a Natronomonas halorhodopsin enhanced for optogenetic applications. Brain cell biology, 36(1–4), 129–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gradinaru V, Zhang F, Ramakrishnan C, Mattis J, Prakash R, Diester I, . . . Deisseroth K (2010). Molecular and cellular approaches for diversifying and extending optogenetics. Cell, 141(1), 154–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson LR, & Frey WH (2008). Intranasal delivery bypasses the blood-brain barrier to target therapeutic agents to the central nervous system and treat neurodegenerative disease. BMC neuroscience, 9(3), S5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkness JE, & Wagner JE (1989). The biology and medicine of rabbits and rodents. In (3rd ed., pp. 372). Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger. [Google Scholar]

- Hofherr A, Fakler B, & Klöcker N (2005). Selective Golgi export of Kir2. 1 controls the stoichiometry of functional Kir2. x channel heteromers. Journal of cell science, 118(9), 1935–1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Wei L, Gu X, Wei Z, Dix TA, & Yu SP (2014). Therapeutic effects of pharmacologically induced hypothermia against traumatic brain injury in mice. Journal of neurotrauma, 31(16), 1417–1430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin JY (2011). A user’s guide to channelrhodopsin variants: features, limitations and future developments. Experimental physiology, 96(1), 19–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitruka BM, & Rawnsley HM (1981). Clinical biochemical and hematological reference values in normal experimental animals and normal humans. (pp. 413). New York: Masson Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Ogle ME, Gu X, Espinera AR, & Wei L (2012). Inhibition of prolyl hydroxylases by dimethyloxaloylglycine after stroke reduces ischemic brain injury and requires hypoxia inducible factor-1alpha. Neurobiol Dis, 45(2), 733–742. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.10.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichler A, Prior JL, & Piwnica-Worms D (2004). Imaging reversal of multidrug resistance in living mice with bioluminescence: MDR1 P-glycoprotein transports coelenterazine. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 101(6), 1702–1707. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0304326101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos EB, Yeh R, Lee J, Nikhamin Y, Punzalan B, Punzalan B, . . . Brentjens RJ (2009). Sensitive in vivo imaging of T cells using a membrane-bound Gaussia princeps luciferase. Nature Medicine, 15, 338. doi: 10.1038/nm.1930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon SM, & Blobel G (1993). Mechanisms of translocation of proteins across membranes In Endoplasmic Reticulum (pp. 1–15): Springer. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Wei ZZ, Gu X, Zhang JY, Zhang Y, Li J, & Wei L (2015). Intranasal delivery of hypoxia-preconditioned bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells enhanced regenerative effects after intracerebral hemorrhagic stroke in mice. Experimental neurology, 272, 78–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki K, Kimura T, Shinoda H, Bai G, Daniels MJ, Arai Y, . . . Nagai T (2016). Five colour variants of bright luminescent protein for real-time multicolour bioimaging. Nature Communications, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsunoda SP, & Hegemann P (2009). Glu 87 of Channelrhodopsin-1 Causes pH-dependent Color Tuning and Fast Photocurrent Inactivation. Photochemistry and photobiology, 85(2), 564–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tung JK, Gutekunst C-A, & Gross RE (2015). Inhibitory luminopsins: genetically-encoded bioluminescent opsins for versatile, scalable, and hardware-independent optogenetic inhibition. Sci. Reports, 5(14366). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei S, Sun J, Li J, Wang L, Hall CL, Dix TA, . . . Yu SP (2013). Acute and delayed protective effects of pharmacologically induced hypothermia in an intracerebral hemorrhage stroke model of mice. Neuroscience, 252, 489–500. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.07.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Cumberbatch D, Centanni S, Shi S. q., Winder D, Webb D, & Johnson CH (2016). Coupling optogenetic stimulation with NanoLuc-based luminescence (BRET) Ca++ sensing. Nature Communications, 7, 13268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yizhar O, Fenno LE, Prigge M, Schneider F, Davidson TJ, O’Shea DJ, . . . Deisseroth K (2011). Neocortical excitation/inhibition balance in information processing and social dysfunction. Nature, 477(7363), 171–178. doi: 10.1038/nature10360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu SP, Tung JK, Wei ZZ, Chen D, Berglund K, Zhong W, . . . Wei L (2019). Optochemogenetic stimulation of transplanted iPS-NPCs enhances neuronal repair and functional recovery after ischemic stroke. The Journal of Neuroscience, 39(33), 6571–6594. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.2010-18.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao S, Cunha C, Zhang F, Liu Q, Gloss B, Deisseroth K, . . . Feng G (2008). Improved expression of halorhodopsin for light-induced silencing of neuronal activity. Brain cell biology, 36(1–4), 141–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Wei ZZ, Zhang JY, Zhang Y, Won S, Sun J, . . . Wei L (2017). GSK-3β Inhibition Induced Neuroprotection, Regeneration, and Functional Recovery After Intracerebral Hemorrhagic Stroke. Cell Transplantation, 26(3), 395–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]